'Mr. Slim's Experience at Sea' (Harper's New Monthly Magazine #9. 1855).

John McLenan was a 19th-century American illustrator and caricaturist, best remembered for livening up the pages of Charles Dickens' 'A Tale of Two Cities' (1859) and 'Great Expectations' (1859-1861). In the case of the latter title, he was the original illustrator. McLenan was one of the house cartoonists of the U.S. magazine Harper's Weekly. Some of his cartoons make use of a sequential text comic format, with narration appearing underneath the images. McLenan is one of the earliest U.S. comic artists to make series about recurring characters, namely 'Mr. Slim' (1855) and 'Mr. Elephant' (1857-1858). His drawings not only show dynamic slapstick action, but also make early use of close-ups. However, McLenan's career was tragically cut short by his early death at age 37-38.

Life and career

John McLenan was born in 1827 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, but grew up in Cincinnati, Ohio, where he worked in a meat packing company. According to legend he was discovered by engraver DeWitt C. Hitchcock while making drawings on top of the barrels. In reality, McLenan's drawings already appeared in The Enquirer in the mid-1850s, before Hitchcock offered him a job at Harper's Weekly. During the 1850s and 1860s, McLenan's illustrations could be found in The New York Picayune, the Jolly Joker, Harper's New Monthly Magazine and Harper's Weekly. Particularly in the latter magazine, McLenan was one of the main cartoonists and illustrators, alongside Theodore R. Davis, Winslow Homer, Livingston Hopkins, Henry Mosler, Thomas Nast, Granville Perkins and Alfred & William Waud.

Illustration from 'Great Expectations'.

Charles Dickens

While first and foremost a widely read news magazine, Harper's Weekly also serialized novels by established authors such as William Makepeace Thackeray and Charles Dickens. One such book was Charles Dickens' historical novel 'A Tale of Two Cities' (1859), set during the French Revolution. In the United Kingdom, this story had been serialized in the magazine All the Year Round, where it was illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne. Since U.S. readers hadn't read it yet, it was easy for Harper's Weekly to let one of its own artists, McLenan, create new illustrations when the story ran in their magazine between 7 May and 3 December 1859.

The same happened when Harper's Weekly obtained the rights to another Dickens classic, 'Great Expectations' (1860-1861). Since the British serialization of 'Great Expectations' in All the Year Round had been without illustrations, it made McLenan the novel's first illustrator. But when 'Great Expectations' appeared in book form, Marcus Stone was instead assigned to liven up the pages. Later artists who have illustrated this timeless story about Pip the orphan have been Henry Louis Stephens, F.W. Pailthorpe, Matthew Bock, F.A. Fraser and Harry Furniss. In the 1960s, John M. Burns adapted 'Great Expectations' into a comic for the Scottish publisher DC Thomson. Compared with other Dickensian illustrators like Robert Seymour, George Cruikshank and John Leech, McLenan never reached the same amount of fame, alhough he remains notable as the only original Dickens illustrator who hailed from the United States instead of the United Kingdom.

Other book illustrations

Apart from Charles Dickens, McLenan also illustrated 'The Woman in White' (1859) and 'No Name' (1860-1862), two novels by Wilkie Collins previously also serialized without illustrations in the British magazine All the Year Round. McLenan's final illustrated novel was Edward Bulwer-Lytton's 'A Strange Story' (1862). His talent drew comparisons with the British illustrator Hablot Knight Browne, who signed with "Phiz", and some even nicknamed him "the American Phiz".

'Life Insurance, A Dream' (1856).

Mr. T. Square

During his short career and lifespan, McLenan was also a comic pioneer. The text comic 'How Mr. T. Square Prepared His Picture For The Academy' in the first volume of The New York Journal (August-December 1853) is attributed to him. The story features a comical character, who goes through absurd lengths to have his portrait painted for the Academy. Only one sentence appeared underneath each image, allowing for an easy read, but also made for a very outstretched story which lasts five pages.

Mr. Slim

In issue #63 (August 1855) of Harper's New Monthly Magazine, McLenan introduced another humorous text comic, 'Mr. Slim's Aquatic Experience'. It features a comic character going out for a swim on Coney Island Beach. Slim tries to change into his bathing suit, but the door of his bathing box keeps swinging open, making it difficult for the embarrassed Slim to avoid being seen half naked. When he eventually runs into the sea, a wave makes him go under water. He is helped by a friend and one scene later Slim mistakes a group of female swimmers for mermaids. Another wave makes him lose his swimming shorts. As he tries to put them back on, while fighting the power of the waves, he decides to leave the water. But there on the beach, a whole crowd of spectators has gathered to stare at this strange, clumsy man. Embarrassed, Mr. Slim changes clothing again, but the grumbling beach tourist isn't too happy with the fact that it took so long to "dry himself with a wet towel covered with sharp sand."

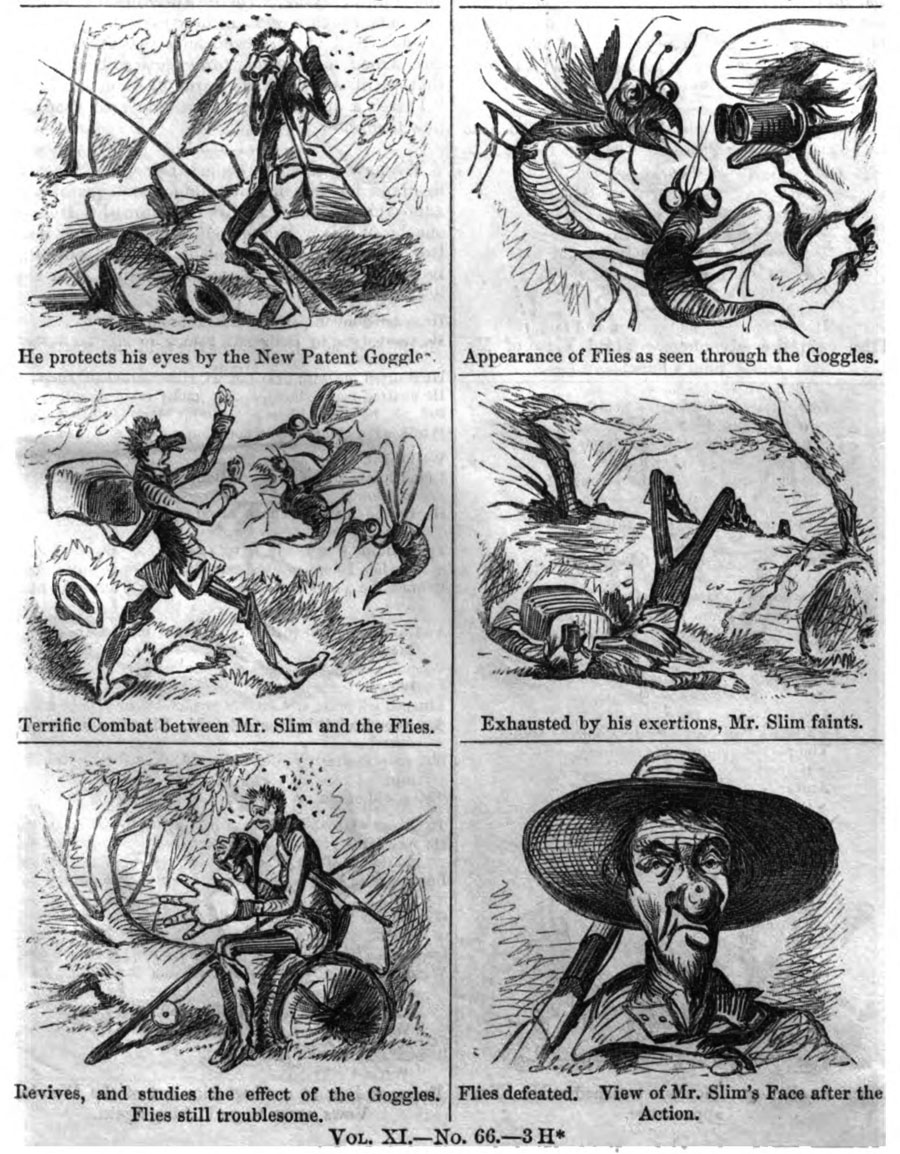

'Mr. Slim's Final Piscatorial Experience' (Harper's issue #66, November 1855).

In the next issue of Harper's, #64 of September 1855, Slim returned in a brand new adventure, 'Mr. Slim's Experience at Sea'. This time he travels by boat, but the shaking ship makes him constantly bump into things, while waves splash him wet. The story ends with Slim going to sleep in his state room, wondering whether he'll get seasick. Slim's final unlucky adventure, 'Mr. Slim's Piscatorial Experience', is also his longest. It was serialized in two parts, 'Mr. Slim's First Piscatorial Experience' was printed in Harper's issue #65 (October 1855) and 'Mr. Slim's Final Piscatorial Experience' in issue #66 (November 1855). This time Mr. Slim goes fishing, but falls in the river and his fishing rod keeps catching anything but fish. First the hook injures a painter sketching in the woods. Slim offers him some alcohol, which the artist "accepts as his apology" as the ironic narration reads. Next, Slim's rod accidentally catches a bird. He decides to put a fly on the hook, while other "flies" (actually mosquitoes) buzz around his face. To protect himself, Slim puts on goggles, but these magnify the mosquitoes, making him think he's surrounded by monsters. Unaware of what he's doing, he trips over a tree trunk and faints. After recovering, his face is full of mosquito bites. All things considered, Mr. Slim seems to be a genuine landlubber, unfit to be near water, be it the ocean or a river.

The 'Mr. Slim' stories are among the earliest examples of a character-based comic series in the United States. McLenan used Mr. Slim in three separate narratives. While 'Mr. Slim's Aquatic Experience' and 'Mr. Slim's Experience at Sea' are self-contained stories, 'Mr. Slim's Piscatorial Experience' is a two-parter, making it one of the earliest serialized picture stories in the USA. Mr. Slim's adventures are told in a text comic format, with text captions underneath the images. McLenan grew as an artist too. The scenes in 'Mr. Slim's Experience at Sea', where his protagonist is shaking back and forth on deck, show great dynamism in his actions. In 'Mr. Slim's Piscatorial Experience', McLenan also makes use of close-ups. He zooms in on the fishing equipment that Mr. Slim wants to take along with him. In the scene where he looks at the magnified mosquitoes buzzing around his face, close-ups are used again. The insects are turned into grotesque but wonderfully imaginative monsters, giving an early example of a nightmarish sequence in U.S. comics. Tto underline his punchline, McLenan also uses a close-up of Slim's mosquito-stung face in the final panel.

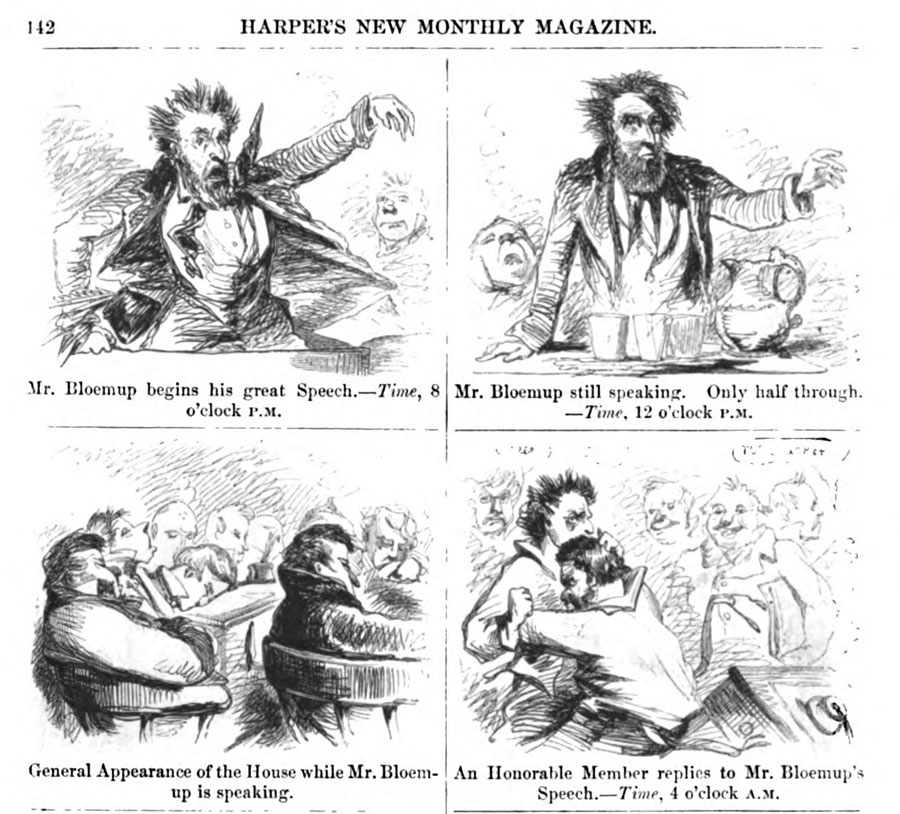

'Hon. Mr. Bloemup's Congressional Experience' Harper's New Monthly Magazine issue #67 (December 1855).

Mr. Bloemup

In Harper's New Monthly Magazine issue #67 (December 1855), McLenan introduced another comical character, the honorable politician Mr. Bloemup. In his first and only adventure, 'Hon. Mr. Bloemup's Congressional Experience', Bloemup goes to the U.S. Congress, attending political debates. McLenan offers a cynical view of the congressmen, who all either argue and fight like infants or bore each other with long-winded speeches that don't accomplish anything. Bloemup is no different from his fellow congress members. He hangs on his chair in undignified poses and prides himself for making "a great speech" that in reality is written by a hired ghostwriter. McLenan cleverly uses his panels to provide humorous contrasts. In one scene, for instance, the reader sees what Mr. Bloemup imagines the congressmen look like (a series of dignified gentlemen), followed by "the reality" (a bunch of ugly red-nosed drunks). In another, he satirizes "two eras in the life of a petitioner", with an "interval of 20 years". The young speaker is now an old man and "his bill not through yet". In some of the backgrounds, characters use speech balloons.

Mr. Elephant

In issue #87 of Harper's New Monthly Magazine (August 1857), McLenan introduced another recurring character in the story 'Elephantine Metamorphosis'. The picture story shows an anthropomorphic elephant in various humorous situations, like singing opera or balancing on his trunk and afterwards his tail, and professions, including actor, balladeer and fireman. More than a year later, in issue #101 (October 1858), the pachyderm made a comeback. In 'Mr. Elephant at Mrs. Potiphar's Grand Soiree', he now receives a name, Mr. Elephant, and is seen making a fool of himself at a private party.

'Mr. Elephant at Mrs. Potiphar's Grand Soiree' (Harper's New Monthly Magazine #10, October 1858).

Other comics

McLenan made many other one-shot text comics for Harper's, often of a satirical nature. In issue #61 (June 1855) he drew 'Comicalities, Original and Selected', a series of humorous stand-alone cartoons, while in issue #68 (January 1856), the magazine ran 'Life Insurance - A Dream', a text comic poking fun at what can go wrong despite being insured. Again McLenan uses some speech balloons in the background panels. In the next issue, #69 (February 1856), the story 'Valentines Delivered in Our Street', is also notable for early use of balloons to indicate characters speaking. In 'Experiments in Photography' (issue #75, August 1856) and 'Family Daguerrotypes Found Every Where' (issue #86, July 1857), the still young artform photography is ridiculed. McLenan contrasts the idyllic ways we imagine things to be with the confrontational harsh reality in 'Imagination versus Reality' (issue #91, December 1857). 'Frangipanni's Sleigh-Ride, and What Came of It', uses a stereotypical Italian to create some snow-themed slapstick. It ran in Harper's New Monthly issue #92 (January 1858). With 'Private Gallery, Collection of Moses Levi, esq.' (issue #95, April 1858), McLenan satirized the pompous behavior of people in an art gallery.

As a regular book illustrator, it was not all that surprising that McLenan noticed a lot of clichés in popular novels. He highlights them in 'Ingredients of a Modern Novel' (issue #96, May 1858), which is almost a forerunner of the satirical comics found a century later in Mad Magazine. 'Mr. Flasher's Love at First Sight' (issue #97, June 1858) follows the laughable attempts of Mr. Flasher to win the girl of his dreams. The tale shows obvious influence from Rodolphe Töpffer's similar narrative, 'Histoire de Mr. Jabot'. 'Grab's Great Gift Enterprise' (issue #98, July 1858) follows an unsuccessful entrepreneur. More irony followed with 'An Affair of Honor' (issue #102, November 1858), a story in which the characters are anything but honorable. 'Arrowsmith's Panorama of Modern Travel' appeared in Harper's issue #103 (December 1858), satirizing the travel industry, while 'Experiences of a Dramatic Author' (issue #104, January 1859) mocks writers. McLenan indulged in black comedy with 'Noodles's Attempts at Suicide' (issue #105, February 1859). His story 'Mr. Bottle and His Friend' in issue #110 (July 1859) is reminiscent of George Cruikshank's picture story 'The Bottle'.

"The Flight of Abraham" (Harper's Weekly, 9 March 1861).

Political comics

During the late 1850s and early 1860s, McLenan's comics became more satirical. In 1858-1859, the USA led a military expedition to Paraguay, after Paraguayan soldiers had fired upon an American ship and killed one American crew member three years earlier, in February 1855. Many expected a war, but once the troops had arrived in the country, a peace settlement had been reached. Paraguayan president Carlos Antonio Lopez gave a public apology for the 1855 shooting, compensated the slain sailor's family and signed a commerce and navigation treaty with the U.S. McLenan made a sequential cartoon about this military conflict for the 30 April 1859 issue of Harper's Weekly, titled 'How the People At Home Supposed The War Would End'/'How It Did End'. The first panel shows a war, the second shows the peace agreement.

On 9 February 1861, Harper's Weekly published a one-shot comic by McLenan titled 'The North and the South'. It depicted the U.S. North and South arguing while a black slave looks on in the background. In the final panel they all embrace in agreement, because Harper's wanted to stay neutral in the whole real-life argument about the abolition of slavery. Unfortunately, real life was less idyllic and a mere two months after this comic strip was published, the U.S. Civil War broke out.

On 9 March 1861, John McLenan made a comic strip for issue #219 of Harper's Weekly titled 'The Flight of Abraham (As Reported By A Modern Daily Paper)'. The four-panel story was based on a real anecdote about U.S. president Abraham Lincoln when he visited Baltimore. A stranger told him that there was a plot to assassinate him and that it would be advisable to instantly leave the city in disguise and return to Washington, D.C. Told in a text comics format, all captions underneath the panels are direct quotations from a newspaper article. The illustrations themselves are more comical, complete with dialogue in speech balloons drawn from McLenan's own imagination.

McLenan made another sequential illustration for Harper's Weekly, published on 12 July 1862. A "before/after" cartoon, it references U.S. general Benjamin Butler, whose troops occupied New Orleans at the time. Most citizens naturally didn't like the occupation and there had been reports of women showing their contempt to the soldiers by demonstrably avoiding looking at them, turning their back sides, walking away and even spitting. On 15 May 1862 Butler issued a general order (no. 28) which instructed his troops to treat any woman in New Orleans who insulted them as a prostitute. The cartoon depicts women spitting on Butler in the first panel, "before Mr. Butler's proclamation" and then acting normal to him in the second panel after the law went into effect.

Death and legacy

John McLenan died young. He was only 37-38 years old when he passed away in 1865. It has not been recorded what caused his early death, but it likely contributed to his art falling into obscurity for several centuries.