Satirical comic by Mogorosi Motshumi (2024), depicting South African Minister of Communications & Digital Technologies Mondli Gungubele and President Cyril Ramaphosa.

Mogorosi Motshumi is a South African cartoonist, comic artist, graphic novelist and author. Active in the Black Conscious Movement (BCM) since the 1970s, he was briefly arrested in 1980. In 1981, he collaborated with Andy Mason in drawing 'Sloppy' (1982-1994), a humorous, yet socially conscious comic character. After three years, Mason relocated to Durban and, from 1984 on, Motshumi continued the feature on his own. This made 'Sloppy' a long-running comic series drawn by a black South African. Two years later, Motshumi drew sports cartoons for the Sunday newspaper City Press for two years and went on to do the same for the popular tabloid Daily Sun. He later also became the first black South African to publish an autobiographical graphic novel, '360 Degrees' (2005). The book was also translated into French.

Early life and career

Mogorosi Motshumi was born in 1955 in Batho, Bloemfontein, South Africa. He was raised by his grandmother while his parents were elsewhere trying to make a living. At around age 12, he developed a love for comic books and read all kinds, including photo comics like 'The Spear', 'Chunky Charlie' and 'She'. He also devoured Harvey Comics and British soccer comics like 'Hotshot Hamish', 'Nipper' and 'Roy of the Rovers'. One summer his brother introduced him to Marvel Comics and characters like Spider-Man and The Incredible Hulk blew him away. He loved the fact that even with their super powers which they used in pursuit of justice, they were still vulnerable in their everyday lives, making it easier for the reader to connect with them.

Growing up as a black man in Apartheid South Africa, Motshumi grew to hate authority, represented in his mind by white people and the police, both black and white. He remembered as a nine year old, riding in the back of a police van to visit a white superintendent, having to explain why his grandmother couldn't pay her rent. Then there was the curfew for black people, starting at 20.50 (p.m.) and announced by a siren. It was a warning for people to leave town. When the second siren went off at 21.00, every black person still in town was arrested and hauled off to jail. Motshumi also remembered the resentment he felt towards his mother when he was carted off, mid-school term, to a one-horse town called Zeerust, to go and join her where she married a policeman. Back in Bloemfontein after a two year spell in Zeerust, his grandmother sent him off to boarding school some sixty kilometers away because he started showing signs of rebellion and often hung out with what she described as "ragamuffins".

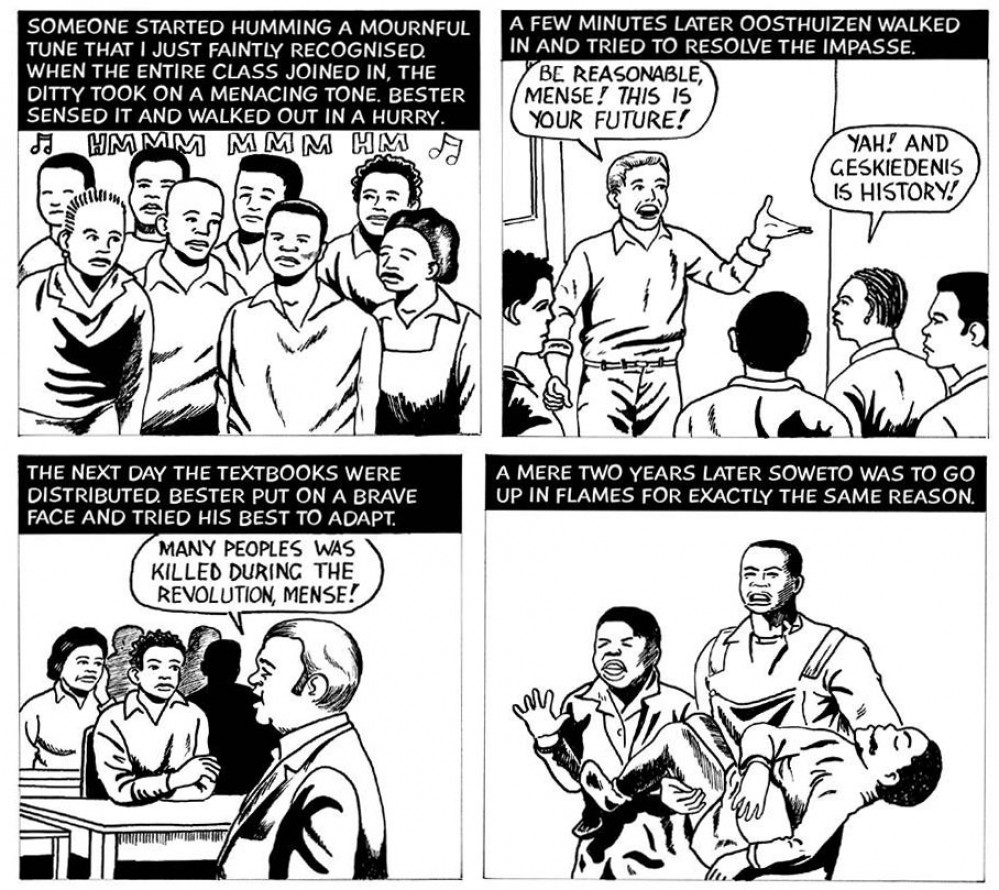

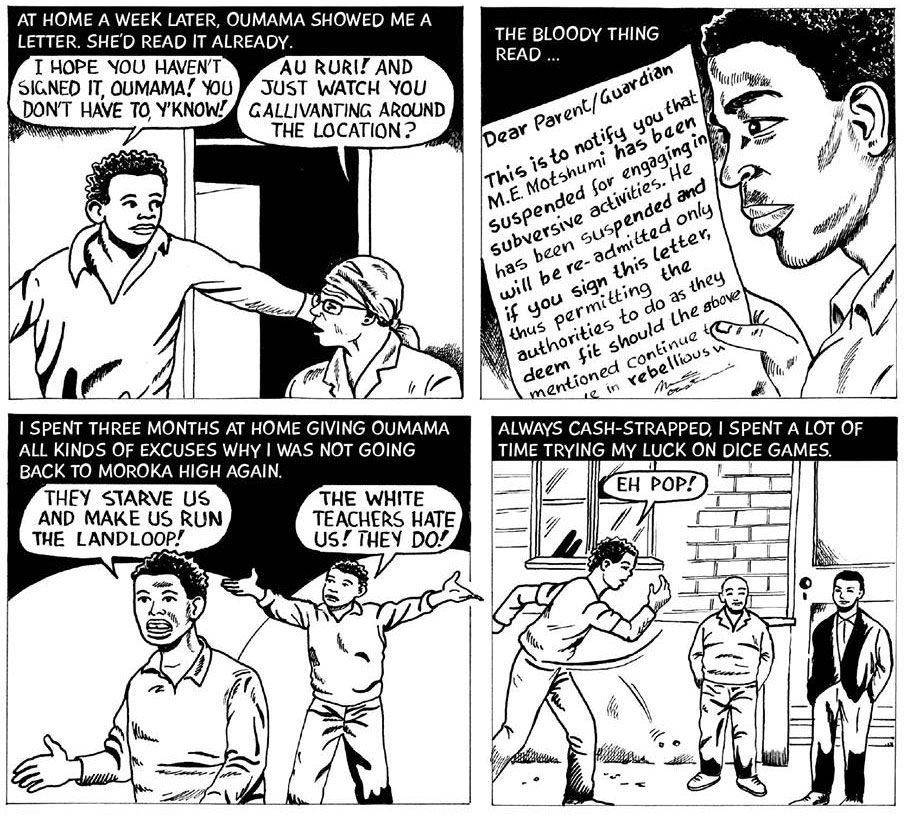

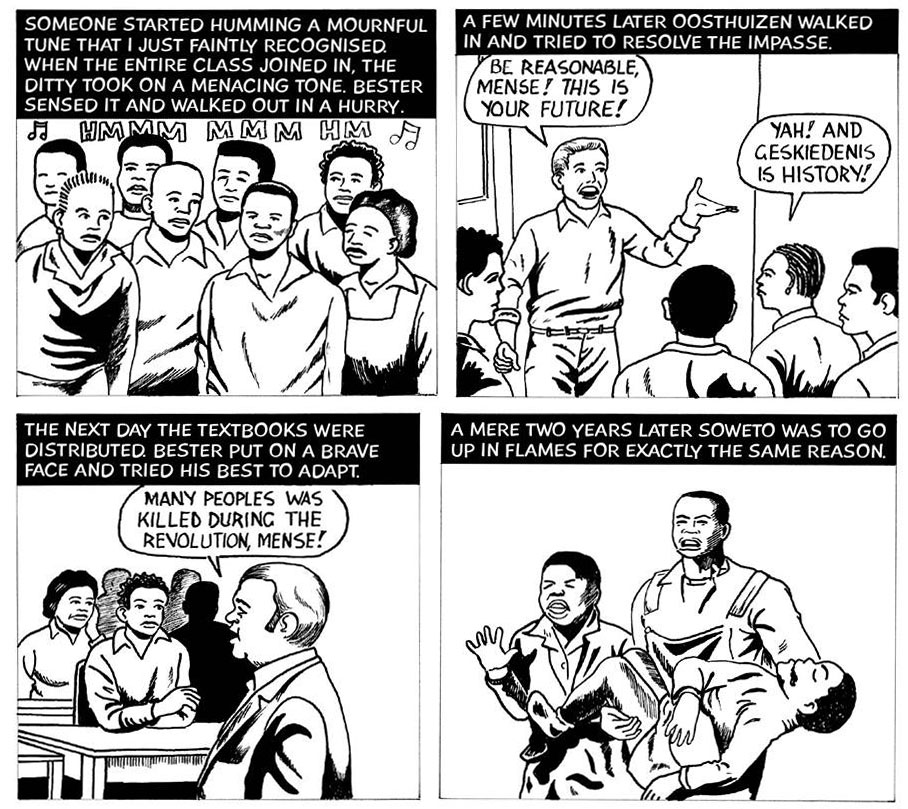

One day, Motshumi's teacher asked him to either groom or shave off the unkempt hair he had cultivated to assert that rebellion. The next day, Motshumi came back to class with the same hairdo, but the teacher decided to ignore him. The following year and in the middle of the term, the school head issued an ordinance that all History lessons would now be given in Afrikaans, regarded by a majority of blacks as the language of the oppressor. The pupils refused to obey and boycotted classes. Soldiers were called onto the school premises to break the boycott. Some pupils yielded and resumed classes. Motshumi was among those who were sent home. Two years later, in June 1976, an uprising erupted in Soweto, fueled by the exact same reasons. One of the most personal downsides of Apartheid was that there were no art colleges for black people in South Africa. Going to a white art college was not legally possible. So out of bleak reality, Motshumi took several other odd jobs, including stocker, transporter, salesman and administrator.

Autobiographical scene from: '360 Degrees'.

Early cartooning career

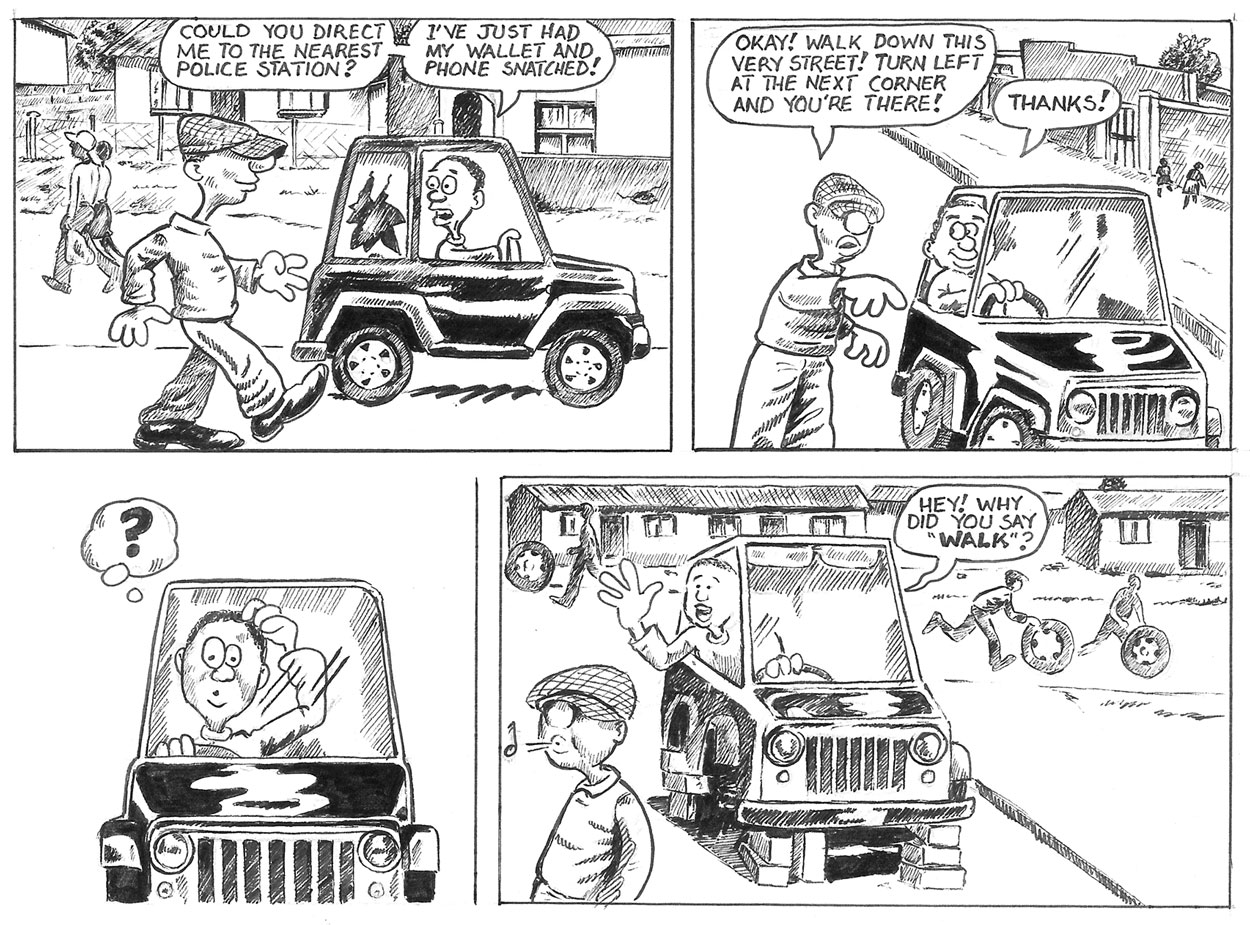

Motshumi became a freelance police cartoonist in 1977, working for the regional newspaper The Friend. A freelance reporter had interviewed him for the paper, which motivated the sub editor to hire Motshumi to draw cartoons for the "township edition". At the time, The Friend published two separate issues, one for white readers, another for black ones, often with different content. While Motshumi enjoyed his new job, his cartoons were very critical of the government and its Apartheid politics. Every evening, at 9 o'clock, black people were alarmed by a siren to return to their ghettos before curfew. Motshumi was expected to refrain from drawing about national politics in favor of white cartoonists, like John Jackson, but he went ahead anyway. Unfortunately, many of his cartoons were therefore rejected, which made it difficult for him to cash in his monthly payments, since technically few of his works had been printed. As a result, Motshumi additionally worked as a court interpreter for a while, but thanks to tremendous reader demand, he was eventually allowed to return to The Friend.

Meanwhile, Motshumi had joined his wife and Benny Morake in establishing the cultural group Malimu, which held poetry recitals around the country. In April 1980, he went to Lesotho by invitation of the activist Isaac Moroe (of the Black Conscious Movement), returning with several pamphlets promoting the illegal Anti-Apartheid organisation ANC. Back home, he was arrested for possession of these pamphlets and jailed for two weeks. Since the police couldn't find the pamphlets, he was released again, but Motshumi discovered he had been fired from his job. Remembering the assassinations of other prominent Anti-Apartheid activists like Ongkopotse Tiro (1974) and Steve Biko (1977), he decided it was safer to flee his hometown and leave his partner and one-month old son for a while. Although he eventually wanted her to join him, she felt his hiding-out, the capital Johannesburg, wasn't the best place to raise a child. Motshumi and his wife later divorced.

In Johannesburg, Motshumi found employment as a reporter and editorial cartoonist for The Voice. He also drew a political comic strip for the publication, 'Motshumi's Country', as well as a weekly comic serial, 'In the Ghetto'. He additionally wrote poems and made illustrations for the cultural magazine Staffrider. At this latter magazine, he also met fellow cartoonist Andy Mason, who would remain his foremost creative collaborator for decades to come. Compared with the previous decade, Motshumi now had more creative freedom, while meeting several other cartoonists all intent on overthrowing Apartheid, such as Mzwakhe Nhlabatsi, Percy Sedumedi, Fikile Magadlela, Matsemela Manaka, Nape Motana and Mpikayipheli Figlan.

Sloppy

Mosthumi and Andy Mason (who sometimes signed with N.D. Mazin) were the prime graphic and lay-out contributors to the adult educational magazine Learn and Teach, established in September 1981. Learn and Teach was intended for people who wanted to expand their knowledge of the English language, offering a variety of topics. All articles were written in basic English. Starting with the January 1982 issue, Motshumi and Mason created their comic series 'Sloppy' (1982-1994), which closed off every issue. Each episode was a short, self-contained story featuring the big-nosed youngster Sloppy, his girlfriend Lizzie and their friends Dumpy and Gladys. While most were straightforward humor tales, 'Sloppy' also offered a recognizable view of everyday life in the black townships, while simultaneously providing black readers with crucial information about their rights. In issue #4 of 1982, for instance, Sloppy is fired on the spot by his boss, but Dumpy confronts the boss with the fact that he should still pay Sloppy according to the law, or otherwise he'll call his lawyer. The boss gives in, while the readers are given a moral if they would ever find themselves in such a situation. At the time, no other South African magazine let a black cartoonist draw stories about such topics. Originally, Motshumi and Mason took turns in drawing and writing, but when Mason moved back to Durban, Motshumi continued the series on its own, sometimes assisted the scriptwriter Steve Rothenburg.

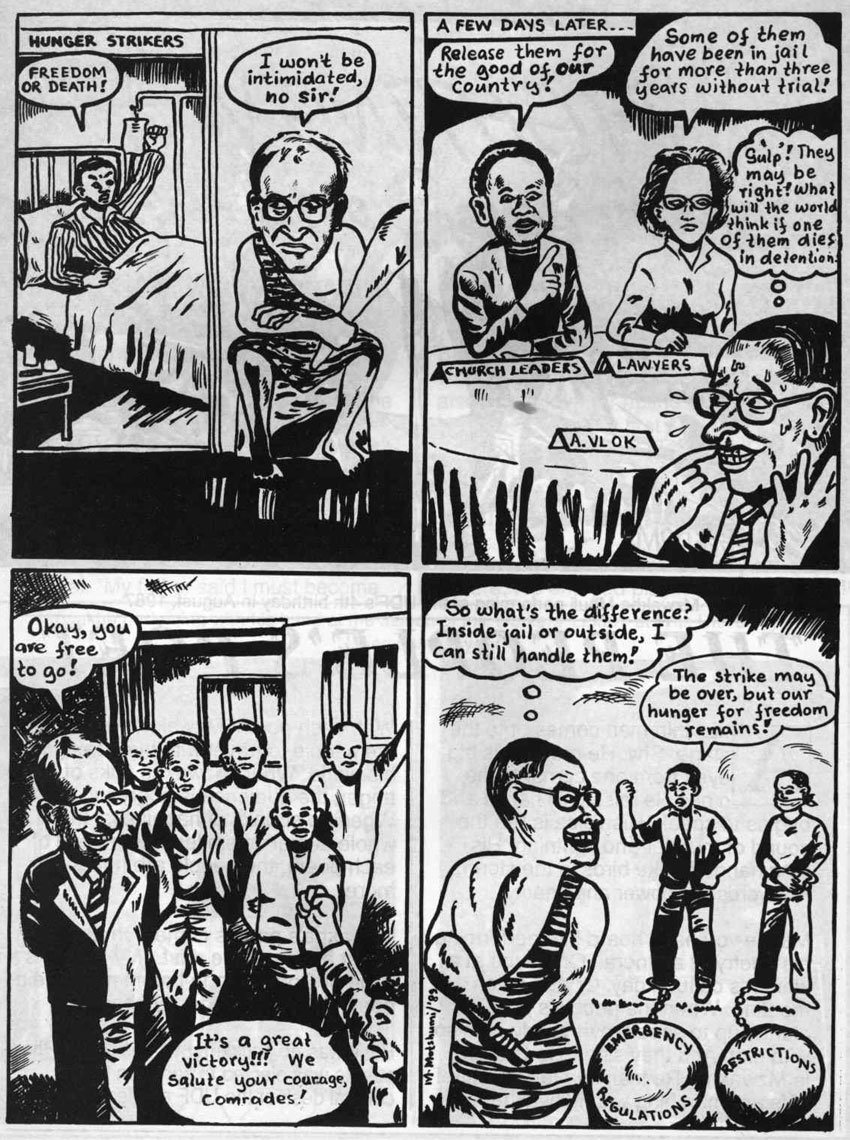

'Upfront', satirical comic from Learn and Teach #1, 1989, depicting South African Minister of Law and Order Adriaan Vlok.

Even though he had fled his hometown, Motshumi didn't work under a pseudonym, because he wanted the authorities to know that he was still in the country. He continued the series for more than a decade, except for a brief period in 1988 when he had broken his hand and the magazine had to rely on reprints for a while. Motshumi also drew longer 'Sloppy' stories, which were serialized over several issues. Ironically enough, while Learn and Teach supported the Anti-Apartheid movement throughout the 1980s and eventually saw the wretched system crumble by 1994, the magazine itself also folded that same year. Since the battle was over, it could no longer rely on funding from Anti-Apartheid organizations.

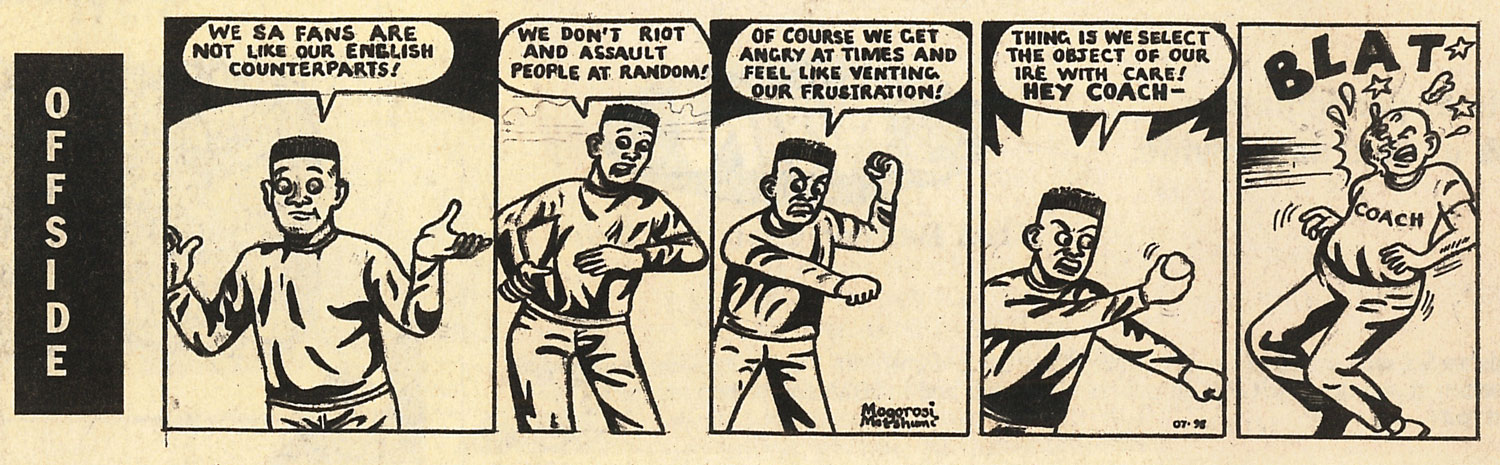

When Learn and Teach folded, Motshumi designed posters for labor unions and drew sports-themed comics for the newspapers City Press and Daily Sun. His feature 'Offside' (2 August 1998-2000) ran in the Sunday pages of City Press, while Daily Sun ran 'The-Fun' for a year.

Jake Ntuli biography

Although on the political front the struggle against apartheid had been won by the early 1990s, Motshumi soon faced a new, personal battle. In 1989, a doctor discovered an ulcer in the cornea of Motshumi's right eye. It was controlled with medication for some time but came back with a vengeance in 1993. Whenever he read or drew for extended periods, he was plagued by headaches. Around the same time, Motshumi was diagnosed with HIV. The South African government was unable to deal with this pandemic, which led to numerous quacks giving people unhelpful "medical" advice. It wasn't until Motshumi's former Learn & Teach colleagues intervened that he was able to receive proper medication from privately owned chemists.

Motshumi also found a new passion project. A few years before Learn & Teach folded, he had written an article for them about legendary flyweight and bantamweight champion Jake Tuli (1931-1998). Under apartheid laws, though, Tuli was officially recognised as a "Non-European" champion, with his counterpart Marcus Temple being pigeonholed as a white champion. The two could not fight to decide who was the legitimate "king", since fights between black and white boxers were prohibited by law. Tuli did get to spar with a white boxer, though, namely world bantamweight champion Vic Toweel. With only a wad of cotton wool as his mouthguard, Tuli gave Toweel such a torrid time that Toweel's father cut the session short. As there were no prospects of further growth, Tuli went to the United Kingdom where he shocked the boxing world by dethroning veteran champion Teddy Gardner in only his eleventh fight as a professional, and in the process became the first African to win a British Empire Flyweight title. After reading this article, editor Suttner encouraged Motshumi to write a full biography: 'The Demon and the Angel: The Story of Jake Ntuli' (Viva Books, 1999). Unfortunately, it arrived a year too late. Tuli had passed away a year earlier. Although happy with the publication of his first book, Motshumi didn't like the way it was adapted and felt many things had been left out. John Stodel, a veteran film and television producer, nevertheless still wanted to make a movie based on the book. Contracts were signed, but then Stodel suddenly died. In 2020, Motshumi finally decided to do something about his unhappiness with the Tuli biography, and began working on the graphic novel version where he feels he can retain more control of the editorial content.

'360 Degrees'. The fourth panel references Sam Nzima's famous photo of the 1976 Soweto Uprising.

Autobiographical graphic novels

Around 2005, Motshumi and Andy Mason met in Johannesburg's Melville. After a meal at one of the many pavement restaurants, Mason asked Motshumi to do a twenty-page comic about his life for his comic, MAMBA. After the publication of the comic, Motshumi got a call from Rui Tenreiro, a Mozambican visual artist now based in Sweden, who felt Motshumi had more to tell and encouraged him to do a more detailed work. In 2005, Motshumi returned to his city of birth Bloemfontein to find additional inspiration for his autobiographical comic '360 Degrees' (X Libris). The graphic novel follows his childhood years, his rising political consciousness and his career in comics, but also pays attention to personal issues like his divorce, alcoholism, family tragedies and health problems. The first volume, 'The Initiation' (Xliberis, 2016), was self-published with help from his colleagues Andy Mason and Su Opperman. At a barbecue to celebrate the publication, Mason and his friends decided to raise money to help Motshumi get an eye operation. The second volume is titled 'Jozi Jungle' and was published and translated in French by Éditions Cambourakis. The third volume is still a work in progress at this time of writing (2024).

Mogorosi Motshumi's son Atang Tshikare is also active as an artist.

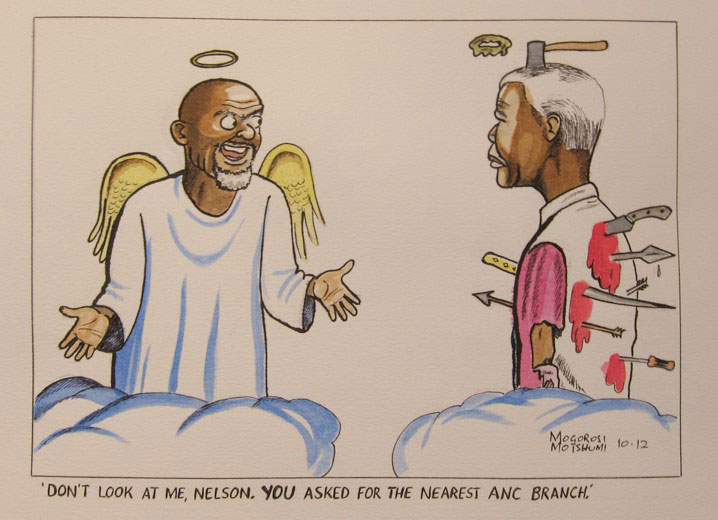

Nelson Mandela cartoon from October 2012, referencing a 2004 quote by Mandela that he hoped that after death, he "could join the nearest ANC branch in the afterlife." Motshumi wondered a year before Mandela's actual death whether the former ANC leader would still want to be associated with the ANC, since corruption and violence had effectively changed their public image.