'Les Mésaventures de M. Bêton'.

Léonce Petit was a 19th-century French caricaturist, engraver, illustrator and painter. He is best remembered for his comic serial 'Les Mésaventures de M. Bêton' (1867-1868). This humorous adventure story led to comparisons with the Swiss cartoonist Rodolphe Töpffer, whom Petit imitated. However, most of Petit's other illustrations and comics are more realistically drawn, with a specific dedication to the French countryside.

Early life and career

Léonce Justin Alexandre Petit was born in 1839 in Taden, Côtes-d'Armor. He grew up in the Brittany countryside, where his father was a landowner. It gave Petit his lifelong poetic outlook on the lives of farmers and shepherds. He was a pupil of the painters Henri Harpignies and François Augustin Feyen-Perrin. Among Petit's other graphic influences were Rodolphe Töpffer, Gustave Doré, Honoré Daumier and Jules Baric. Despite his artistic ambitions, Petit studied Law in the city. For a short while, he worked as a registry office clerk in Auvergne, before moving to Paris in 1863.

'L´Oeuf d’ânesse' (Le Journal Amusant, January 1874).

Le Journal Amusant

Petit's graphic talent landed him a job with the satirical weekly magazine Le Journal Amusant, where he remained a contributor until his death. He mostly created caricatures and crowd illustrations, depicting peasant scenes, inspired by Jules Baric. One of them, 'Le Pardon de Saint-Gildas-des-Bois' (1866), shows a religious festival divided in 18 images. The work is not only notable for the use of illustrated sequences, but also because Petit uses captions beneath the illustrations, similar to a text comic. 'La Noce du Garde-Champêtre' (1867) is a similar picture story about the wedding of a small town police officer.

Le Roman d'une Cuisinière

In 1866, Petit wrote 'Le Roman d'une Cuisinière, Raconté par son Sapeur' ("The Novel of a Cook, told by her Sapper"), an illustrated novel published by Les Éditions Guérin. It was a humorous story about a cook returning from Africa and trying to get used to French city life. The book became a best-seller, but got panned by Émile Zola, who at the time was still a literary critic and not yet the famous novelist and essayist. "I cannot believe," he scorned, "that the public ever wanted such a book, nor can I believe that anyone could have written it out of pleasure."

Les Aventures de Mr. Tringle

However, 'Le Roman d'une Cuisinière' caught the attention of another novelist, Jules Champfleury, who asked Petit to illustrate his short story 'Les Aventures de M. Tringle'. The narrative had been published a year earlier as a straightforward text, without illustrations. Mr. Tringle is a man who decides to go to a costumed ball dressed as the Devil. Unfortunately, he arrives on the wrong date and finds himself all alone in his silly costume. As he returns home, he is mistaken for a real demon and chased away by his female servant, a priest, a bunch of oxen and a group of children. The text comic version was serialized in magazine L'Illustration between July and August 1867, and released in book format a year later. It reached a wider audience than Champfleury's original. This time, even Zola praised the work.

'Les Mésaventures de M. Bêton'.

Les Mésaventures de M. Bêton

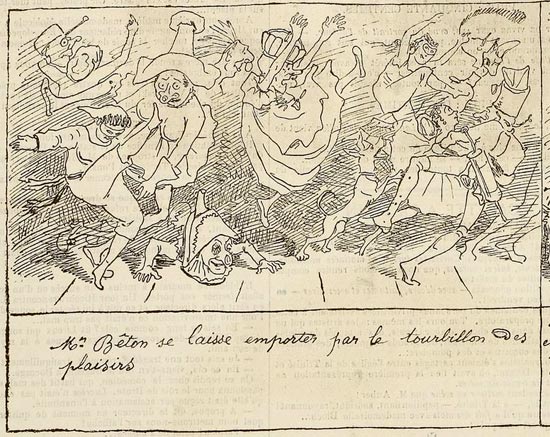

In 1867, Petit joined the magazines Le Hanneton and Le Bouffon. A year later, his drawings could be seen in L'Eclipse. During this period, he created the humorous comic strip 'Les Mésaventures de M. Bêton' (1867-1868), which follows a rather awkward slapstick narrative. Mr. Bêton hails from Valognes and travels to Paris with his dog and a stuffed crocodile that belonged to his father. During a bumpy train ride, he grows fond of a chubby woman. Unfortunately, the train has an accident and the machinist is thrown outside, losing all his clothes in the process. The police instantly arrest him for public indecency. Bêton and his female companion survive the accident and go to a local village festivity, where they dance until a policeman breaks up their fun. When they walk past the prison, they help the machinist escape, but the man instantly steals the women's dress to wear it himself. The trio is then hired by traveling acrobats to perform as a freak show act. The machinist plays a bearded lady, while Bêton and his female friend dress up as dancing African tribespeople.This part of the story openly portrays transvestism and a bare-breasted woman in a grass skirt.

'Les Mésaventures de M. Bêton'.

Halfway through their act, Bêton and the machinist suddenly refuse to perform any longer, much to the dismay of the ringmaster. A fight breaks out and Bêton falls on the back of a Turkish spectator. He piggybacks him out of the hall. Meanwhile, the police enter the scene. A soldier falls in love with the machinist and, thinking he's a woman (despite the obvious beard), he takes him along. Something similar happens to Bêton's female friend who, still half nude in tribal dress, is helped by a member of the Society for Protection of Animals. Bêton himself is still piggybacking on the Turk who jumps on an omnibus and murders everybody on the rooftop, including the coachman. The vehicle plunges into the river Seine, where Bêton is saved from drowning by countess Trognonette. She likes his dancing style so much that he becomes her chaperon at the Opéra ball. Yet her personal guard feels Bêton dances too close to her and interferes. In the chaos, Bêton runs away and falls into a sewer. He manages to crawl out again and returns to his village. His female friend saves the bearded machinist from being assaulted by the horny soldier and together they continue their way.

A large part of 'Mr. Bêton' was serialized in Le Hanneton, from March 1867 until the magazine was banned in August 1868. Petit finished the story on his own, whereupon it was published in book format by Librairie Internationale Lacroix & Verboeckhoven & Co. Since the story resembled Rodolphe Töpffer's picture stories so much, it earned Léonce Petit the lasting nickname "The French Töpffer". In the article 'Cartooning in the Age of Realism' on the website www.19th-artworldwide.org, author Philippe Willems argued that this designation misrepresents both artists' work.

'Les Bonnes Gens de Province' (Le Journal Amusant, 23 January 1869).

Style

Most of Petit's illustrations have a bucolic spirit and show everyday events in the French countryside. A good example is 'Moeurs Champêtres' (1869), a satirical cartoon series ridiculing country people, published in Le Journal Amusant. In 1871, Petit drew a series of picture stories for Le Petit Journal under the title 'Histoires Campagnardes' ("Country Stories"), which were collected in book format too. One of his most popular features was 'Les Bonnes Gens de Province' ("The Good People of the Provence", 1874), a humorous look at everyday life in Provence. Many panels show panoramic crowd scenes of various villagers. About 200 episodes were printed in Le Journal Amusant as well as Le Petit Journal Pour Rire. By popular demand, they were also collected in book format.

Paintings

As a painter of country scenes, Petit was closely associated with the Realistic movement and the School of Barbizon. In 1869, his works were exhibited at the prestigious Salon des Beaux-Arts in Paris, but critics only gave lukewarm to mild reviews. Petit was a shy and humble man, which might explain why his work didn't get as much attention as more iconic names like Gustave Courbet, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot or Jean-François Millet. Another possibility is that his fame as a caricaturist and illustrator made him an inferior artist in the eyes of "connoisseurs". In 1875, one of Petit's paintings was simply rejected from the Salon. Historians have considerable evidence to believe that this decision was politically motivated, since Petit was somewhat of a left-wing bohémien.

Final years and death

In 1873, Petit published work in the satirical magazine Le Grelot. Between 12 October and 9 November 1873, he contributed the text comic serial, 'Comment on devient réactionnaire, où les palinodies d'Agénor Pistochard' ("How one becomes reactionary, or the palinodes of Agénor Pistochard"), which was serialized in issues #131 through #135. The satirical story follows a student, Agénor Pistochard, who has strong political opinions, though more out of pose than any real conviction. When he learns that he inherited a fortune, he turns from a reactionary wanting to abolish the system into a snobby upper class conservative. From 1874 on, Petit's drawings were present in La Fronde as well. Between 1882 and 1884, he decorated the pages of L'Almanach du Père Gérard, Le Petit Journal pour Rire, Le Monde Illustré and the children's magazine Saint-Nicholas.

In 1877, Petit was asked to join his friend Paul Sébillot in establishing the magazine La Pomme, of which the first issue was published on 12 April of that year. In 1881, he married and had a daughter one year later. Sadly, he didn't live long. During the final decade of his life, Petit suffered from gout. It made him bed-ridden and unable to work for days on end. Completely paralyzed in the end, Léonce Petit passed away in 1884 at the age of only 45.

Legacy

In 1895, a street was named after him in Dinan, not far from where he was born. A memorial plaque, sculpted by Etienne Leroux, was added in July 1896. His daughter, Madeleine Léonce-Petit, was a well known illustrator in her own right.

'Croquis d'été' - 'Joies et douleurs' (L'Eclipse #150, 1874).