Hubert Van Zeller was a mid-20th century Egyptian-British Benedictine monk, theologian and sculptor. Under the pseudonym "Brother Choleric", he also drew humorous cartoons, published under the title 'Cracks in the Cloister' (1954-1976). They poke fun at life in monasteries, with Van Zeller satirizing and caricaturing both himself and monks and nuns he knew personally. The cartoons polarized readers due to the erudite language, inside jokes and melancholic comedy. In later years, Van Zeller's cartoons also addressed the changes of the Second Vatican Council and more modernizations.

Life and career

Hubert Claude Van Zeller, nicknamed "Dom" by his friends, was born in 1905 in Alexandria, Al Iskandariyah, Egypt, back then still a British protectorate. His family was of Dutch-Flemish descent. In September 1914, he went to Downside School in Somerset, England, and at age 19, he joined the local monastery, Downside Abbe. After a short-lived desk job as an office clerk and later filling in a Carthusian monastery, Van Zeller eventually settled permanently on a life as a Benedictine monk. Between 1957 and 1959, he served at the Catholic parish at Talacre, was headmaster at Downside and chaplain at Ladycross Prep School in Sussex. Van Ziller was so devoted to his religious principles that his only personal possessions were a typewriter and a toothbrush. Only when he was diagnosed with a serious illness, he decided to adopt a less rigid lifestyle.

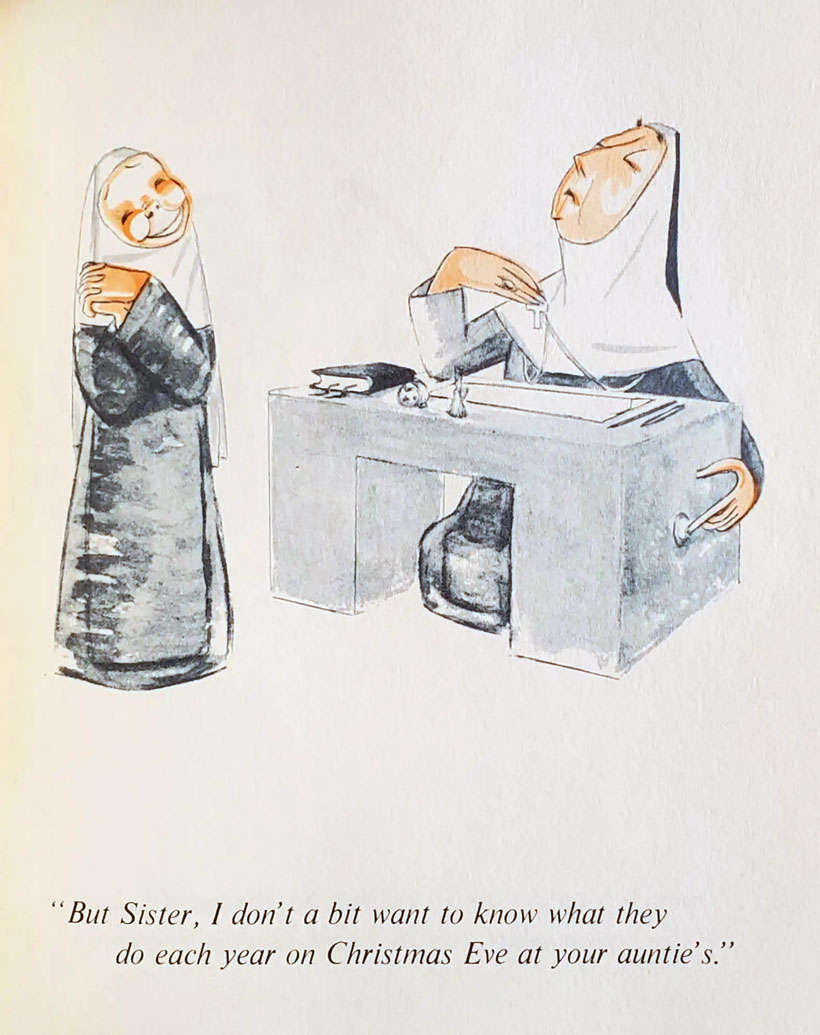

Van Zeller was a notable theologian. He wrote more than 40 books about his faith, including 'Ezechiel' (Sands & Co, 1944), 'We Work While the Light Lasts' (1950), 'Daniel: Man of Desires' (The Newman Press, 1951), 'The Outspoken Ones: Twelve Prophets of Israel and Juda' (Sheed & Ward, 1955), 'Approach to Prayer' (Sheed & Ward, 1958), 'Approach to Monasticism' (Sheed & Ward, 1960), 'A Book of Private Prayer' (1960), 'Sanctity in Other Worlds' (1963, later retitled 'Holiness: A Guide for Beginners'), 'A Death in Other Words' (Templegate, 1963), 'Moments of Light' (Templegate, 1963), 'The Psalms in Other Words: A Presentation for Beginners' (Templegate, 1964), 'The Will of God in Other Words: A Presentation for Beginners' (Templegate, 1964), 'The Mass in Other Words: A Presentation for Beginners' (Templegate, 1965) and 'The Trodden Road' (1982). In his writings, he used humor, sometimes livening up the pages with descriptive illustrations. Van Zeller tried to keep a worldly view, not shying away from addressing his own personal struggles and recurring health problems while analyzing life through the lens of his devout convictions. His books are still reprinted today.

'Ezechiel', 1944.

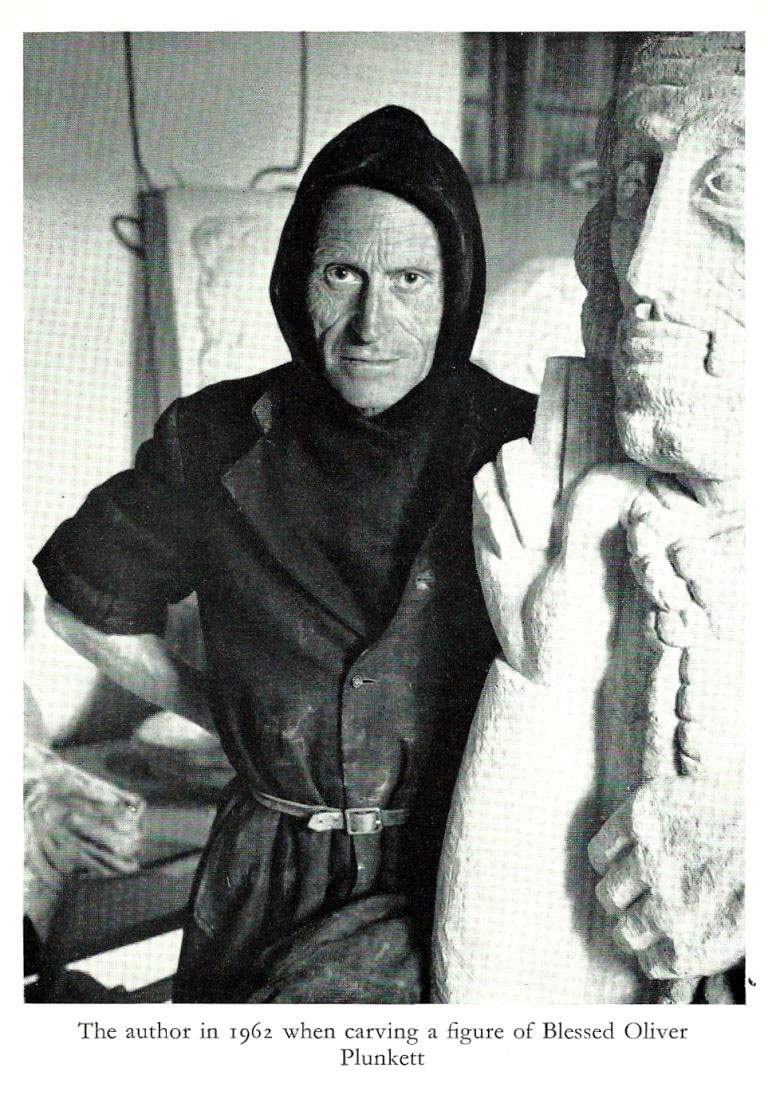

Van Zeller was also an accomplished sculptor, despite never having academic training. His interest was sparked when he was a young boy, observing an Egyptian boy carving designs into a piece of driftwood. Many of his works were made for churches, monasteries and other religious buildings. He also wrote a book about his passion: 'Approach to Christian Sculpture' (Sheed & Ward, 1959). Van Zeller was a close friend of fellow Christian scholars Ronald Knox and Fr. Bede Jerret, and he also corresponded with novelist Evelyn Waugh (of 'Brideshead Revisited' fame). Waugh once named Van Zeller "the Max Beerbohm of the cloister".

In 1950, Van Zeller first visited the United States and would revisit it many times. In 1978, he moved to Denver, Colorado, spending his days in St. Walburga's Abbey in Virginia Dale and afterwards at the Little Sisters of the Poor house in Denver. In 1983, he moved back to England, where he passed away a year later in Stratton-on-the-Fosse. Somerset, at age 79. 'One Foot Out of the Cradle' (John Murray, 1965) is his autobiography.

'Cracks in the Cloister' and 'Further Cracks in Fabulous Cloisters'.

Cartoons

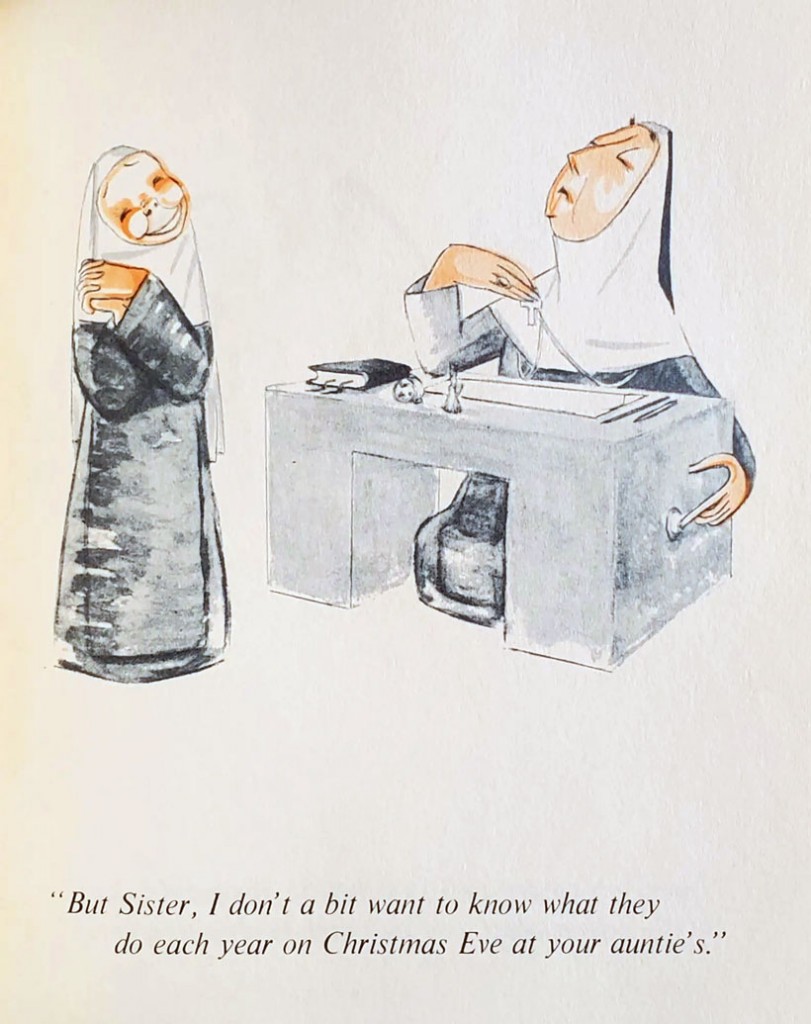

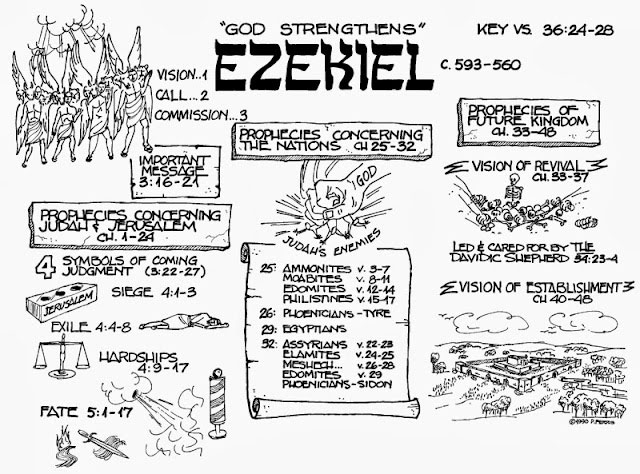

Van Zeller drew various cartoons, collected in the books 'Cracks in the Cloister' (1954), 'Further Cracks in Fabulous Cloisters' (1957), 'Last Cracks in Legendary Cloisters' (1960), 'Posthumous Cracks in the Cloisters' (1962), 'Cracks in the Curia: Brother Choleric Rides Again' (1972) and 'Cracks in the Clouds' (1976). The titles were published by Sheed & Ward. Except for 'Cracks in the Clouds', printed under his own name, all previous books were signed with the pseudonym Brother Choleric. They appeared in Catholic publications and were also translated in several languages.

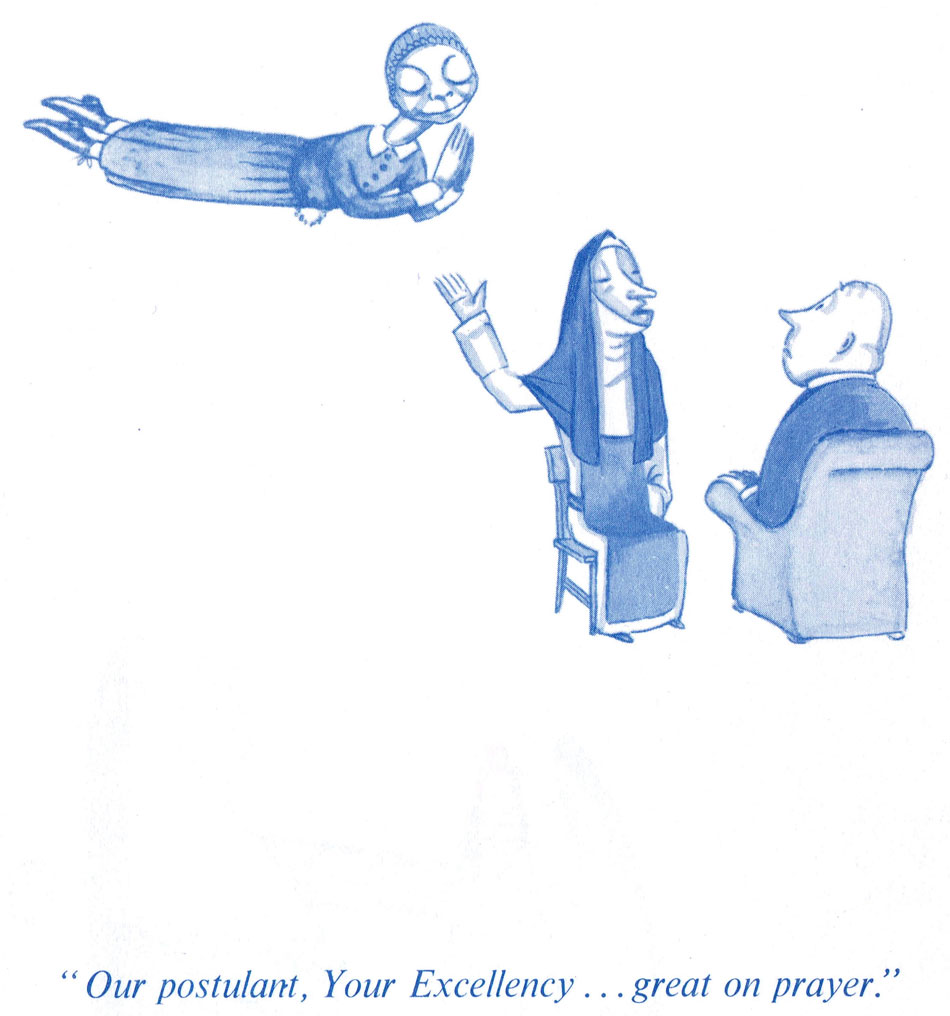

Van Zeller's humorous cartoons are all set in monasteries, featuring monks and nuns. Many are caricatures of real-life people Van Zeller used to know and so drawn accordingly. This might also explain why he chose to publish under a pseudonym. The punchlines are sometimes straightforward, but other times more understated, written in high-brow language with very literary words and expressions. For people unfamiliar with Roman-Catholic liturgy, they may sometimes be difficult to understand. This, in combination with the caricatures of his friends and colleagues, gives some gags a light-weight satirical undertone, at times almost on an inside joke level.

While cartoons about jolly monks and nuns aren't unusual, Van Zeller's work is different in the sense that he was an actual monk and could offer a first-person perspective. Like other Christian cartoonists, his comedy can be gentle, but unlike them, it often also has a melancholic undertone. His characters aren't idealized. They are fallible human beings, expressing frustrations, anger and even occasional contempt for one another. Abbots and head nuns can be rather smug, while young brothers and sisters are well-meaning, but also naïve. Van Zeller portrays the monastery as a secluded, self-contained world of its own, where its inhabitants can sometimes feel out-of-touch with life outside its walls. When published in Catholic magazines, some reviewers complained about Van Zeller's cartoons, either because they disagreed with this melancholic worldview, or because they didn't "get" the punchlines. In an article for Monastiek Tijdschrift voor Vlaanderen en Nederland (issue #29, 2013), Charles van Leeuwen suggested that these "angry" reviews and readers' letters may have been written by Van Zeller himself to promote his work and give it more attention. On the other hand, Van Leeuwen also mentions that some monks actually felt offended by Van Zeller's cartoons. One named them "nonsense", while another said: "If this monastery had more people like you, there would be less people like me."

After World War II, Van Zeller observed secularism growing stronger in Western society, with many people rejecting religion and even self-professed Christians no longer attending Church on a regular basis. As early as 1960, he illustrated the novel 'Logic for Lunatics' (1960) by John Coulson. The plot satirizes an arrogant, delusional atheist who eventually joins the Church in a predictable moralistic ending. As the 1960s progressed, Pope John XXIII implemented the Second Vatican Council (1961-1962), which brought radical changes to the traditional Roman-Catholic teachings. Van Zeller showed strong resistance against these modernizations, particularly the abolishment of traditional Latin-language mass in favor of preaching in the language of the churchgoers, to make the teachings more understandable to them. A fierce traditionalist, Van Zeller wrote a letter to the editor of The Tablet in 1970, explaining why he wanted permission to continue the old form of Latin-language mass: "(...) My criticisms are not levelled at the Pope but at the people who have taken advantage of the liberty left by the Pope in liturgical matters, and who have, over the past few years and with the unhappiest results, experimented. It is not Rome's fault that permission to use the vernacular has been abused and that hymn-singing has in most churches ruled out the possibility of silent prayer. My own preference, I admit, is for the old rite and for the traditional language, but I hope I shall be allowed to go on saying a daily Mass until the end of my days—even if it has become for me more a penance than a prayer. Since the Mass is essentially a sacrifice, and one which invites a corresponding sacrifice on our part, I am quite ready to do without recollection and even peace of mind if this is what God wants. God evidently does want it or he would not have spoken so clearly through his appointed authority."

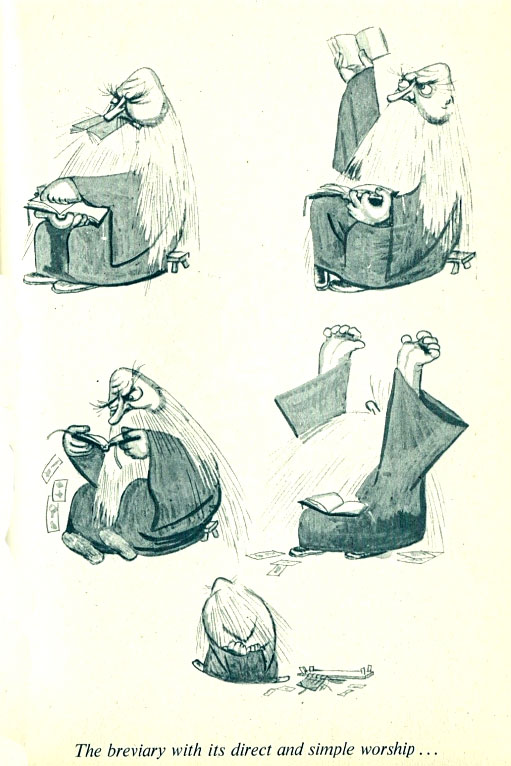

Sequential cartoon by Brother Choleric.

In 1962, Hubert Van Zeller even named one of his books 'Posthumous Cracks'. In the foreword, he claimed that Brother Choleric had died "an early death": (...) "While he was doing canonical penance for decapitating his last Abbot, he was visited by Sister Annabella Fructuosa. This good nun, by reading him long extracts from the mediaeval mystics, made him resolve to abandon his former ways. The sudden change brought about a sharp deterioration in health and with his last gasp he gave an order that his cartoons should be burnt. But there was a contract! We had the cartoons and his signature. No more was needed." (...) There's no truth in the rumour that a Brother Choleric memorial fund has been started." In reality, Van Zeller simply wanted to quit drawing cartoons after too many angry reactions from fellow monks.

Nevertheless, new cartoon books were still published afterwards, but his comedy gradually grew more sour. Most of the punchlines revolve around the growing secularisation, the Second Vatican Council changes and the increasingly more complex modern world to which clergymen and -women found it more difficult to adapt. In one cartoon, two priests are jailed. One for "saying Mass in English before the Decree", the other "for saying Mass in Latin after the Decree". In another drawing, a nun hands over part of her traditional uniform, with the "punchline": "I ask myself, where will it all end?". In his final cartoon book, 'Cracks in the Clouds' (1976), Van Zeller even titled one of his drawings 'More in Anger than in Sorrow', depicting a group of priests watching TV from the comfort of a sofa. One says: "It's nice to know that in being permissive years ago, before the Council, we were right all along." Van Zeller also took jabs at more modern theologians, like Hans Küng.

Despite the controversy surrounding Hubert Van Zeller's cartoons, they were bestsellers. But for a long while, few people knew who was behind the pseudonym "Brother Choleric". It took until the arrival of the Internet before his identity was pieced together. Even in his autobiography, Van Zeller only devoted one page to his cartoons, which he described in rather vague terms as "jolly books".