'Saint Croce' (1504), with prototypical speech balloons.

Hans Burgkmair the Elder was an early 16th-century Bavarian painter and woodcut printmaker. Some of his paintings and woodcuts show sequential illustrations, making them early examples of prototypical comics. His painting 'Saint Croce' (1504), for instance, depicts Jesus' life in panels and uses speech balloons. The woodcut engraving 'Wechselndes Glück' (1527) visualizes the ups and downs of life in a picture story. Together with Florian Abel, Lucas Cranach the Elder, Jeremias Gath, Hans Holbein the Elder, Hans Holbein the Younger, Bartholomäus Käppeler, Caspar Krebs, Georg Kress, Hans Rogel the Elder, Hans Rogel the Younger, Erhard Schön, Johann Schubert, Hans Schultes the Elder, Lucas Schultes and Elias Wellhöfer, Burgkmair is one of the earliest German prototypical comic artists who has been identified.

Life and work

Hans Burgkmair was born in the spring of 1473 in Augsburg, Swabia, in the Duchy of Bavaria, then part of the Holy Roman Empire, today located in Germany. His father, Thomas Burgkmair (also spelled as "Thoman"), was a painter and thus Hans was brought up in an artistic household. The boy studied printing and engraving in the German town Kolmar, under the guidance of Martin Schongauer. Unfortunately, Hans' mentor died in 1491, before his schooling could be completed. Afterwards, Burgkmair worked for the Augsburg printer Erhard Ratdolt. In 1498, he opened his own studio in the same town.

Burgkmair established himself as a productive painter and woodcut artist. He made several Christian-themed paintings and portraits of important citizens in his hometown. Three of the six paintings in the St. Catherine Monastery of Augsburg are by his hand. Burgkmair was regularly commissioned by Maximilian I, King of the Romans (1486-1519) and Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire (1508-1519). He made several paintings and woodcuts glorifying the monarch and other members of his court.

Burgkmair is credited as the first woodcutter to use a "tone" block. In 1508, he started using flat areas of color, which gave the woodcut blocks contrasts in light and dark. This "chiaroscuro" technique was particularly neat when shading had to be suggested. It gave scenes more depth and dramatic impact. Another pioneer in tone blocks was fellow German artist Lucas Cranach the Elder, who experimented with the technique around the exact same time. From 1510 on, Burgkmair's designs were modified into woodcuts by the Flemish artist Jost de Negker. De Negker was incidentally also his main printer and distributor.

Hans Burgkmair passed away in Augsburg, somewhere between May and August 1531, at age 57 or 58. His son, Hans Burgkmair the Younger, was also a painter.

Prototypical comics

Some of Burgkmair's woodcuts feature sequentially illustrated narratives. Most were made for propaganda purposes by commission of Maximilian I of the Holy Roman Empire. The monarch personally oversaw the storylines and what ought to be depicted on the images. Yet in some he didn't directly depict himself, but rather a heroic alter ego. So many writers and artists contributed to his projects that took several years to make. In fact, by the time of the emperor's death in 1519 most were still unfinished.

St. Giovanni in Laterano

In the early 1500s, Burgkmair created a series of paintings intended for the St. Catharina monastery in Augsburg. They depict the lives of famous Christian saints, visualized in a series of consecutive images. Among them St. Peter (San Pietro, 1501), St. Giovanni, AKA St. John in Laterano (1502) and Santa Croce (1504).

Of these three prototypical comics, 'Saint Croce' (1504), is the most interesting. Not only does it portray key moments of Jesus' life in consecutive images, but it also features an early use of speech balloons. In the scenes depicting ships in the harbor, several characters use paper scrolls to talk. Today, these paintings can be seen in the State Gallery of the Old German Masters in the St. Catharina Church in Augsburg.

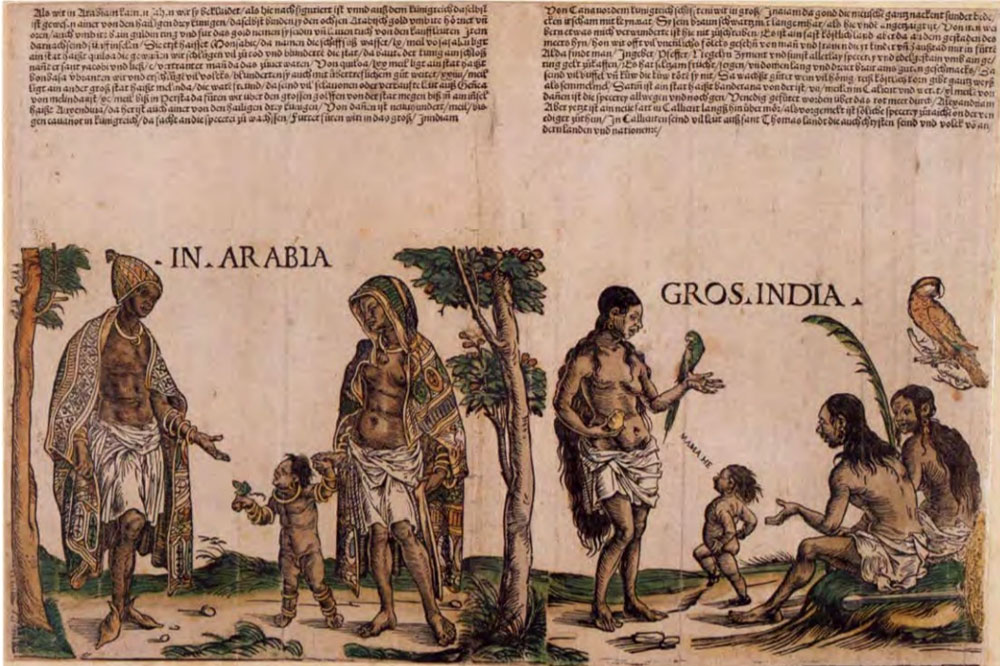

'People of Africa and India'.

People of Africa and India

In 1508, Burgkmair produced the 'People of Africa and India' series. These woodcuts were based on the descriptions of explorer Balthasar Springer who, between 1505 and 1506, traveled from Africa to India. Emperor Maximilian I took a personal interest in other continents, partially out of curiosity, but also for colonial purposes. Historically, the series gives us an idea how white Europeans regarded indigenous people from North African, Middle Eastern and South-Central Asian countries. The 'People of Africa and India' series is additionally notable for featuring events and characters that are thematically connected. They have to be read in combination with the descriptions underneath the images, making them early examples of text comics.

Weisskunig

Burgkmair also worked on 'Der Weisskunig' ('The White King', 1505-1516), a book commissioned by Maximilian I. The story stars a white knight who becomes king with God's blessing. He fights numerous wars to expand his empire. The tale is written in rhyme, with 251 woodcut illustrations by Burgkmair, Hans Schäufelin, Hans Springinklee and Leonhard Beck. 'Der Weisskunig' is basically a romanticized history of Maximilian's own life. The book was never intended for wide circulation and only for the emperor's private circle of friends, associates and noblemen. Unfortunately for Maximilian, it remained incomplete at the time of his death.

Woodcut from the 'Triumphzug'.

Triumphzug

'Triumphzug' ("Triumphal Procession", 1512-1522) was another commission on behalf of emperor Maximilian I. The work depicts an imperial procession, separated over 139 woodblocks, and 54 meters (177 feet) in length. Burgkmair worked on 67 of these woodblocks and designed the majority of the prints. Other contributors were Albrecht Altdorfer, Leonhard Beck, Albrecht Dürer, Wolf Huber, Hans Schäufelein and Hans Springinklee. Their designs were cut by Hieronymus Andreae, Cornelis Liefrinck, Willem Liefrinck and Jost de Negker. The bombastic parade features soldiers, standard bearers, horsemen, musicians, jesters, carriages, animals and indigenous people captured from exotic countries. The separate woodblocks were intended to be put behind one another and read as one long illustration. It could be collected as a decorative frieze on the walls of a city hall or a royal palace, or be bounded in a book. From that viewpoint, it is comparable to one long comic strip. Also in content, since most of the imagery was pure fantasy. In reality, the emperor simply couldn't afford a ceremony of such magnitude. Again he passed away before he could see the work's completion. After his death, Florian Abel and his brothers Bernard and Arnold also worked on a cenotaph devoted to the late emperor, likewise interesting for its use of sequential imagery.

The walking on swords segment of the 'Theuerdank'.

Theuerdank

Another imperial commission by Maximilian I, with Burgkmair's participation, is 'Theuerdank' (1517). This chivalric romance stars the young prince Theuerdank, who longs for the hand of princess Ehrenreich. He sets on a long and dangerous journey to meet her. During his travels, the prince meets three military captains, Fürwittig, Unfalo and Neidelhart, who accompany him. But unbeknownst to our hero, they want to sabotage his plans, since Theuerdank might disband their armies after his marriage. In the end their nefarious obstacles are uncovered. Fürwittig is beheaded, Unfalo hanged and Neidelhart defenestrated. All ends well when Theuerdank and Ehrenreich become engaged. But to ensure their marriage, the brave prince has to go on yet another Crusade. 'Theuerdank' was published in 1517, originally intended for German princes and friends and associates of the emperor. A sequel is hinted on the final page, but again Maximilian's death prevented such a project from ever seeing the day of light.

'Theuerdank' is basically a romanticized version of Maximilian's own life, with Ehrenreich as a stand-in for his real-life wife Mary of Burgundy. He personally dictated the story and even made preliminary sketches, worked out further by professional writers and artists. Besides Burgkmair, other contributing artists were Leonhard Beck, Hans Schäufelein, Erhard Schön, Wolf Traut and Hans Weiditz. Jost de Negker turned their designs into woodcut prints. The final text is written in rhyme and livened up with 118 woodcut drawings.

Wechselndes Glück

In 1527, Burgkmair published another interesting prototypical comic strip titled 'Wechselndes Glück' ("Changing Luck", 1527). This woodcut engraving visualizes the Roman philosophy of the "Rota Fortunae", or "Wheel of Fortune". According to this theory, there's no such thing as constant good or bad luck. People simply experience occasional advantages and disadvantages. In some cases they are suddenly on top of the world for a while, only to come crashing down when they least suspect it. But fortunately the Wheel of Fortune also works the other way around. Even in the utter pit of despair, fortune might be lurking around the corner. Although a Roman concept, the Wheel of Fortune idea was very popular in the Middle Ages and Renaissance too. Burgkmair was just one of several artists to interpret this allegory. On top of his picture story, the line "Wu Der Arm Reich wirt und Der Reich Arm" ("How the Poor become Rich and the Rich Poor") can be read. In a series of successive images, a poor street vendor gradually rises to become a man of power and wealth. But in the final panel he has lost everything. Now sporting a beard, he sits next to a tree, looking at the merchandise he used to sell in his days as a street vendor. Behind the tree, another man points at him, as if to say: "See, I told you."

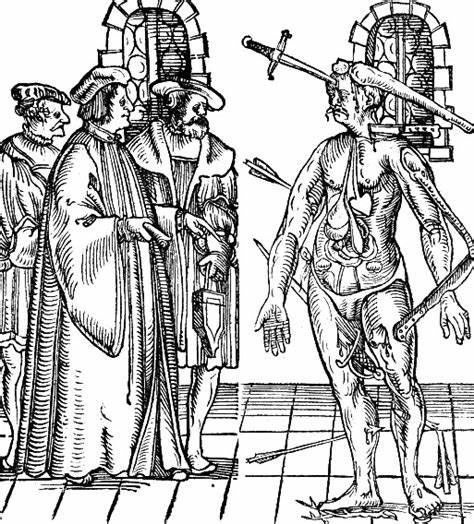

'Wounded Man' by Hans Burgkmair (16th century).