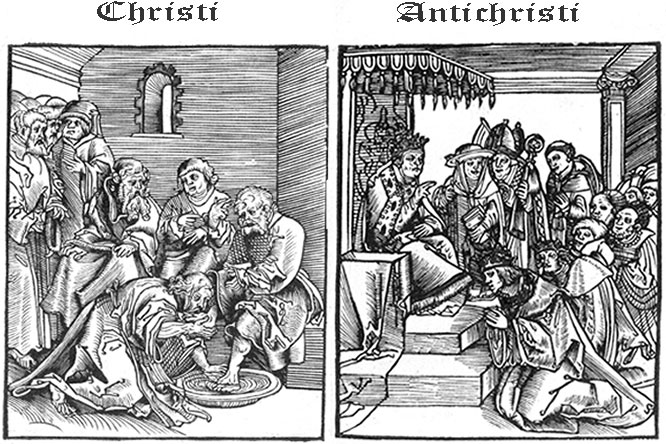

'Passional Christi und Antichristi' (1521). Jesus washing and kissing the feet of a beggar is contrasted with the Pope, whose feet are kissed by visitors.

Lucas Cranach the Elder was an early 16th-century German painter, who was also active as a printer, engraver and woodcut artist. Some of his works are notable for using sequentially illustrated narratives, such as the undated engraving 'Die Jungfrau umgeben von sieben Medaillons, darstellend die sieben Freuden der Jungfrau Maria' ('The Virgin Surrounded by Seven Medallions Representing the Seven Joys of the Virgin') and the painting 'Gesetz und Gnade' ('Law and Grace', 1527), making them early examples of prototypical comics. His illustrated anti-Catholic pamphlet 'Passional Christi und Antichristi' (1521) has been described as an early example of a graphic novel. It contrasts Jesus' life with that of the Pope through a series of comparative illustrations with descriptions written by theologian Philipp Melanchton. Together with Florian Abel, Hans Burgkmair the Elder, Jeremias Gath, Hans Holbein the Elder, Hans Holbein the Younger, Bartholomäus Käppeler, Caspar Krebs, Georg Kress, Hans Rogel the Elder,Hans Rogel the Younger, Erhard Schön, Johann Schubert, Hans Schultes the Elder, Lukas Schultes and Elias Wellhöfer, Cranach is one of the earliest German prototypical comic artists who has been identified.

'Day of Judgment', painted by Lucas Cranach.

Life and work

Lucas Cranach was born in 1472 in Kronach, back then part of the Prince-Bishopric of Bamberg and the Holy Roman Empire, but nowadays located in Germany. His father was a painter. Between 1502 and 1504, Cranach spent some time in Vienna, where his talent caught the attention of Frederick III "the Wise", Elector of Saxony. Cranach became his official court artist and lived in the town Wittenberg until 1520. City records prove that later in life, Cranach resided in the town Gotha. When Frederick III passed away in 1525, Cranach remained court painter for the duke's son, John Frederick I. The artist even moved up the social ladder, becoming mayor of Wittenberg, in 1531 and 1540. In 1550, Cranach moved to Weimar, where he passed away three years later. His sons, Hans Cranach and Lucas Cranach the Younger, his grandson Augustin Cranach and great-grandson Lucas Cranach III, were also painters.

Some of Cranach's paintings show influence from Dutch painter Hieronymus Bosch, who was a contemporary. Cranach copied Bosch's 'The Last Judgment', but also made a more personal and original version of this specific biblical topic. Cranach's 'Last Judgment', painted in the 1520s, shows Christ appearing in the sky, while the chosen ones go to Heaven and the sinners end up in Hell. The demons are very Bosch-esque.

'Der Werwolf oder der Kannibale' (1512). An iconic engraving depicting a werewolf.

Works

Two of Cranach's works are particularly iconic today. The first is his woodcut engraving 'Der Werwolf oder der Kannibale' ('The Werewolf, or the Cannibal', 1512). It depicts a man who slaughtered several people. As he crawls away on his hands and knees, like a wolf, he clutches a baby between his teeth. The gruesome image is still featured today in overviews of werewolf folklore. Cranach was a firm believer in these ancient superstitions. As mayor of Wittenberg in 1540, he was responsible for the arrest, conviction and execution of local skinner Prista Fruehbotin and her son Dictus. They were accused of having poisoned the pastures through magic spells. Although she fled town, she was captured and brought back to Wittenberg. After a trial, she, her son and two of her assistants, Clemen Ziegisk and Caspar Schiele, were burned at the stake for witchcraft. Paranoia was so high that even Prista's other son, Peter, was accused. Like his mother, he fled from town, aided by executioner Magnus Fischer. But a month later, both fugitives were captured in Zerbst and ended up at the gallows. Prista's youngest son, Klaus Frühbott, was lucky. He was declared innocent, but nevertheless banned from the country.

Another famous work by Cranach, 'Der Jungbrunnen' ('The Fountain of Youth', 1546), is also based on ancient myth, visualizing the legend about a fountain that can make old people young again. The seniors dive in the water and come out young again on the other side. Cranach wasn't the only artist to visualize this tale, but his depiction has remained the most popular.

Portraits of Martin Luther by Lucas Cranach (1529 and 1532).

Protestant propaganda

Like most European painters from his era, Cranach mostly created Christian-themed paintings, woodcuts and engravings. But in 1517, a German monk named Martin Luther caused a religious revolution. Outraged by the increasing decadence and corruption within the Roman Catholic Church, Luther felt the original text of the Bible was no longer respected. He attributed this, in part, to the fact that it was only available in Latin, so only educated people could read it. And since most of the European population was illiterate, the majority were unaware of the actual content of the Holy Scripture. They had to rely on what priests told them, which, of course, opened the gates for severe power abuse. The sales of indulgences were perhaps the worst excess. Anybody who had led a sinful life could buy official documents from bishops, with the pope's signature, to "clear" their souls from any wrongdoings. Thousands of naïve or frightened people bought them. Fed up with these malpractices, Luther founded his own religion, Protestantism. He condemned indulgences, protested against the Roman Catholic Church and translated the Bible into German.

Although Cranach kept making art for both Catholic and Protestant taskmasters, he too converted to Protestantism. One only has to look at his sheer mountain of anti-Catholic pamphlets and pro-Protestant works to understand what his real religious conviction was. Cranach also illustrated Luther's Bible translation and made numerous portraits of the man himself. Particularly his 1529 and 1532 portraits are the most iconic and often reprinted images of Luther. Cranach and Luther became such close friends that the painter attended his wedding. Since Luther was originally ordained as a Roman Catholic priest, he was technically forbidden to marry. But as a Protestant priest, these rules didn't apply. Cranach was also godfather of their first child. However, it should also be pointed out that Cranach didn't sign many of his Protestant propaganda works, making it easier to avoid offending potential Catholic clients.

'Die Jungfrau umgeben von sieben Medaillons, darstellend die sieben Freuden der Jungfrau Maria'. The life of the Virgin Mary is depicted in seven medallions.

The Virgin Surrounded by Seven Medallions

Some works by Lucas Cranach are notable for their use of sequential illustrated narratives, making them early examples of prototypical comics. His woodblock print 'Die Jungfrau umgeben von sieben Medaillons, darstellend die sieben Freuden der Jungfrau Maria' ('The Virgin Surrounded by Seven Medallions Representing the Seven Joys of the Virgin Mary') depicts the Virgin Mary, mother of Jesus. She is positioned in the center of the image, with around her seven chronological scenes from her devout life. Each moment is presented in a circle, or medallion. They have to be read clockwise, starting with the image in the lower left corner and ending in the lower right corner. The first scene depicts the angel Gabriel visiting Mary. He informs her that, despite being a virgin, she will receive a son. In the second medallion Jesus is born, with the Three Kings visiting him in the third. After a long skip in time, the fourth image shows the formerly crucified Jesus rising from the grave and ascending to Heaven in the fifth. The Holy Spirit descends on Mary in the sixth medallion, while in the final image she is crowned in Heaven.

'The Virgin Surrounded by Seven Medallions' follows a clear narrative. By separating each individual moment in a circle, Cranach uses an early example of sequential storytelling in panels. The Seven Joys of the Virgin Mary were a popular theme in medieval and early Renaissance art. Several other painters and engravers also visualized this allegory, among them Hans Memling.

'Law and Grace' (1529), a visualization of the life of Adam.

Law and Grace

In 1529, Cranach made the painting 'Gesetz und Gnade' ('Law and Grace'), depicting the story of Adam in a sequential narrative. On the far left of the painting, we see Adam and Eve in Paradise, where he accepts the Forbidden Fruit. On the foreground Adam is chased away, followed by a demon and a skeleton. In the center, Adam is confronted with Jesus' crucifixion and ascension to Heaven. According to Christian teachings, Adam and Eve led mankind into eternal sin, but Jesus' sacrifice on the Cross absolved at least part of these sins, opening the door for human redemption. Adam is depicted three times in the painting, making his spiritual journey a chronological illustrated story. Although all scenes are portrayed in one image, it still appears to be a two-panel sequence, thanks to Cranach's clever position of a tree in the center of the work. Underneath the painting a text can be read. Each written part is divided in small panels, placed directly under the described scene in question. This again allows the painting to be read as a series of individual moments, much like a modern-day comic strip.

'Passional Christi und Antichristi' (1521). Jesus rises to Heaven, in contrast with the Pope who plummets into Hell.

Passional Christi und Antichristi

When Martin Luther first preached Protestantism, his actions were naturally protested by the predominant Catholic community in Europe. The Pope excommunicated him and numerous Roman-Catholic bishops, priests and other clergymen condemned his teachings. One of the fiercest criticisms was 'Antichrist' (1521), a pamphlet by Italian jurist and theologian Ambroglio Catarino Politi. He straight out compared Luther with the Antichrist. Luther read Politi's pamphlet and decided to retaliate. In collaboration with Cranach, theologian Philipp Melanchton and jurist Johann Schwertfeger, they published their own pamphlet, 'Passional Christi und Antichristi' (1521). Melanchton wrote the text, while Cranach livened up the pages with vivid drawings.

'Passional Christi und Antichristi' compares Jesus' life with that of the Pope. On the left pages of the pamphlet readers can see how Jesus was a poor, common man, doing many good deeds. The header above reads 'Passional Christi' ('The Passion of Christ'). This is contrasted with the luxurious and self-serving lifestyle of the Pope, printed on the right pages, under the header 'Antichristi' ('Antichrist'). In 26 woodcut illustrations, Melanchton and Cranach depict the head of the Roman Catholic Church as a decadent, power-hungry despot. Biblical quotes are used to "prove" their accusations. The differences between both church leaders are clear. Jesus' crown of thorns is held against the magnificent papal crown. While Jesus bows to kiss a beggar's feet, the Pope has others bow for him to kiss his own feet. The Messiah preaches peace, but his supposed counterpart on Earth watches violent tournaments and supports wars. Jesus is forced to carry his own cross, but the Roman-Catholic leader is carried by his servants. Cranach's sharpest attacks compare Jesus driving the merchants from the Temple, with the Pope being a Temple merchant all but in name. He sells indulgences to naïve fools who want to be absolved from sins. But justice wins in the end. Jesus ascends to Heaven, while the morally corrupt Pope is dumped in Hell.

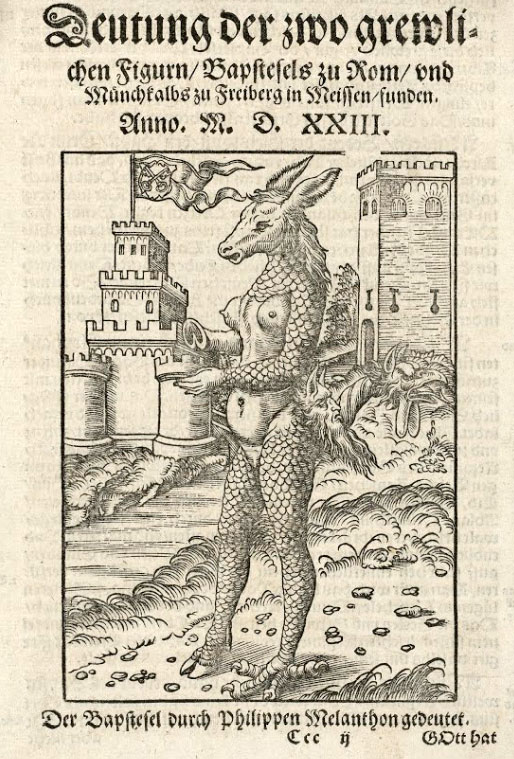

'Der Bapstesel zu Rom' (1523). Cover illustration, depicting the Pope as half donkey, half calf.

'Passional Christi und Antichristi' is anything but subtle. But its message struck a nerve with readers. Although many people couldn't read, Jesus' life was common knowledge among Christian Europeans. And although most had no idea what the Pope's face looked like, they could recognize him by costume. Cranach's drawings were therefore instantly understandable to most readers. While Melanchon's text put everything into context, it's safe to say that the impact could largely be attributed to Cranach's biting and powerful images. Luckily, the authors were smart enough to leave their names of the pages, otherwise they might have ended at the stake. But it convinced Luther that illustrated pamphlets were the best way to reach the masses. Many extra pro-Protestant and anti-Catholic propaganda pieces followed. Thanks to the still recent invention of the printing press, each volume could be duplicated into infinity. Cranach was Luther's most productive illustrator. Another notable satirical broadsheet by him and Melanchton was 'Der Bapstesel zu Rom' ("The Preaching Ass From Rome", 1523). The cover depicts the Pope as a donkey and hybrid between a monk and a calf. The text and illustration referenced an urban legend about a strange creature found in the river Tiber in 1496, combined with the well-known fact that the Pope rode a donkey during papal visits. These pamphlets and more were widely distributed and translated all across Europe. They helped Protestantism become the fastest-growing religion in Europe and a major concern to both the Vatican and many Catholic authorities. It unfortunately also led to fierce religious wars and persecutions, both by Catholics as well as Protestants. Other German artists who made Lutheran propaganda were Erhard Schön and Hans Holbein the Younger.

Historically, 'Passional Christi und Antichristi' is also notable as a very early example of a graphic novel. The reader follows two separate characters, whose deeds are juxtaposed and contrasted. Events from their lives are presented chronologically, complete with a proper start and end. All consecutive panels have a descriptive text underneath. First and foremost, 'Passional Christi und Antichristi' is religious propaganda. In that sense, it could be named a prototypical Christian comic, perhaps even the first example within the Protestant faith. It can also be considered as an early example of a biographical and a satirical comic.

'Ungleiches Paar mit flötendem Knaben' ('Unlikely Couple with Flute Playing Boy', 1540s).

Ungleiches Paar

Cranach also made a series of allegorical paintings titled 'Ungleiches Paar' ('Unlikely Couple'). Although they aren't sequential, they are still interesting for comic historians, since they depict an old, ugly, grotesque-looking husband next to his pretty wife. It provides a humorous contrast, comparable to a cartoonist poking fun at people's facial features. Since "unlikely couples" also exist in real life, it's not surprising that the theme also inspired other artists, including Quentin Matsys and Hendrick Goltzius.

Legacy and influence

Lucas Cranach is regarded as one of the most important 16th-century German painters, along with Albrecht Dürer and Mathias Grünewald. On 27 November 2005, a monument depicting the artist was inaugurated in Wittenberg. The day of his death is commemorated in the Lutheran calendar of saints. Lucas Cranach was an influence on Pablo Picasso.