'Macaronies Drawn After The Life' (1773).

British merchants Matthew Darly and Mary Salmon were mid-to-late 18th-century furniture designers whose London store helped popularize cartooning in the United Kingdom. The pair were the first to exhibit caricatures and cartoons in their shop windows, and their business became very successful through marketing and selling British prints, postcards and books. The material they sold featured caricatures (both humorous and political) and some of these, which contained sequential narratives or speech balloons could be considered prototypes of the modern-day comic. Darly and Salmon compiled many of the humorous images they sold in their store into annual anthologies, and these books raised awareness of cartooning in the United Kingdom. Over time, materials from the Darly's store, particularly inexpensive postcards that cost very little so send, spread the art of caricature to other parts of the world. Matthew and Mary Darly satirized both politics and the fashion trends of their time. Mary Darly was a notable caricaturist, whose prints became fashionable among the very elite they poked fun at. In a case of life imitating art, versions of some hairstyles she ridiculed in her cartoons were later actually worn by the fashionable elite of England. In 1762, Mary wrote the earliest known book about the history of caricaturing, 'A Book of Caricaturas (sic)'.

Early life and career

Although documents of their birth records have not been found, it is estimated that Matthew (Matthias) Darly and his future wife, Mary Salmon, were born in England in the first half of the 18th century. In 1735, Matthew Darly began work as an apprentice for clockmaker Umfraville Sampson. Later in life, as a furniture and ornament designer, Matthew Darly proved to be a versatile craftsman, designing and fabricating all sorts of household items, from tables, chairs and cupboards to ceilings, chimneys, mirrors, tiles and chandeliers. Darly worked as an engraver for the legendary furniture designer Thomas Chippendale, and often collaborated with the printer/ornithologist George Edwards. Together, Edwards and Darly published 'A New Book of Chinese Designs' (1754) and 'A New Book of Ceilings' (1760). On his own, Darly published the books 'Sixty Vases By English, French and Italian Masters' (1767) and 'The Ornamental Architect or Young Artist's Instructor... Consisting of the Five Orders Drawn With Their Embellishments' (1770-1771). When the book was reprinted in 1773, Darly retitled it 'A Compleat (sic) Body of Architecture, embellished with a Great Variety of Ornanaments'. Darly claimed to have worked as an architect before becoming a printmaker. He was also a member of the Incorporated Society of Artists and the Free Society of Artists.

Around 1749, Matthew Darly was married to a woman named Elizabeth Harold. On 28 October 1759, he remarried with Mary Salmon, who then took her husband's name. It is unknown whether his first wife died or that they, uncommon at the time, divorced. Either way, the Darlys had five children: Mary (1761), Mattina (1764), Matthias (1766), William (1767) and Ann (1770). Most accounts claim that by 1756, the couple had their own printshop, located in Hungerford, The Strand, in London. It was named "The Acorn" or "The Golden Acorn", complete with a hanging sign of a golden acorn above the store.

'Bunkers Hill or America's Head Dress' (1776).

Cartoons

Matthew and Mary Darly both enjoyed drawing caricatures. As early as 1741, Matthew published a color cartoon: 'The Cricket Players of Europe'. In the 1750s, the couple got the idea of displaying their funny cartoons on the glass panes of their shop window. This immediately caught the attention of passers by. Many stopped to look, read and laugh at their droll pictures. Word of mouth promotion attracted more people to their store. Mary got the idea of selling these cartoons on smaller-sized prints, comparable to a playing card, which the couple sent by post. From 1756 on, the Darlys bound these cards up as annual books under the title 'Political and Satyrical History of the Year'. Both the cards and books were collected with enthusiasm. Apart from their own work, the Darlys engraved caricatures by other artists and sold paints. Even amateurs were given a chance to print and exhibit their work. The couple launched the careers of Henry Bunbury, Anthony Pasquin and, although this cannot be confirmed, presumably James Gillray too. Upperclass people could take drawing and engraving lessons at their store. By 1758, the couple's store relocated in Fleet Street at West End, to attract bigger crowds.

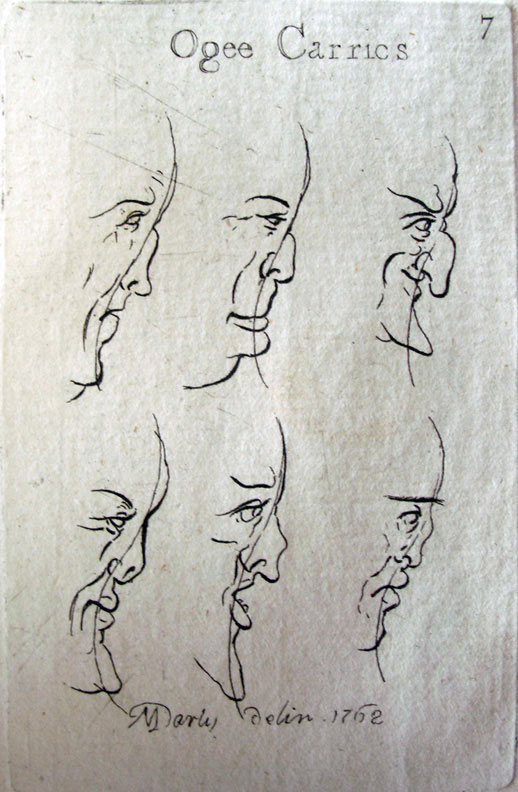

Exactly how Matthew and Mary Darly's cartoons were produced is up for debate. Some are attributed to Matthew Darly, others to Mary Darly. Several have the ambiguous signature "M. Darly". It wasn't uncommon in past centuries for women to publish art under a male name, or for critics to assume a piece of art was made by a man. However, Mary Darly was one of the first to actually enjoy fame as a "female artist", and even as the first female cartoonist who can be identified by signature. She took pride in her profession and named herself "the Fun Merchant, at the Acorn in Ryder's Court, Fleet Street". Given that many of Darly's cartoons dealt with fashion, which is traditionally more a female interest, it seems obvious that Mary drew most of these caricatures herself. There are also enough cartoons published under her own name to assume that she probably drew most of them alone. The title page of one of 'Darly's Comic-Prints' clearly reads "Pubd by Mary Darly". She also published an entire book with caricatures under her own name: 'A Book of Caricaturas' (1762). Caricatures themselves are as old as drawing itself. Artists like Leonardo Da Vinci, Quinten Matsijs, Hieronymus Bosch and William Hogarth offered some of the earliest examples with a signature. The term "caricature", derived from the Italian word "caricare" ("to charge" or "load"), also existed before. But Mary Darly's book about caricatures is the first of its kind in history, by any person! It came with three instructional pages, explaining readers how to exaggerate a person's face.

Cartoon instruction, 1762

The Darly cartoons were extraordinarily popular and many other print shops in the United Kingdom copied the idea. The authorities weren't always amused, though. In 1749, a committee investigated whether the Darlys brought out "obscene" prints. Although the couple originally ridiculed politics, several of their later prints focused stronger on fashion. It is possible that general audiences found this topic funnier, or that apolitical topics were safer. Still, some of their fashion cartoons mixed in political commentary as well. A March 1776 print, for instance, 'Noddle Island or How Are We Deceived', shows a woman with a large, grotesque haircut, on which a fleet, army tents, cannons, flags and soldiers are depicted. It refers to the U.S. War of Independence, when British general Howe was forced to evacuate his troops from the city of Boston. Naturally, most English people interpreted this as cowardice, and Howe was blamed for this "failure". Indeed, the United States eventually became independent, the first colony to do so. Darly made similar "wars depicted on female hairstyles", like 'Bunkers Hill or America's Head Dress' (1776) and 'Miss Carolina Sullivan – one of the obstinate daughters of America' (1776).

Satire is a fickle genre, not always recognized by audiences as such. This was as true in the 18th century as it is today. Mary Darly ridiculed the pompousness and impractability of several hairstyles, dresses, suits and hatwear. Yet at the same time her attention to detail made these ludicrous fashions very attractive. Many people actually started to wear them. A 1773 article in Lady's Magazine describes a woman walking around in a wig "large enough to accommodate an entire stepladder within its tresses" and directly compares it with a Darly cartoon, presumably 'Ridiculous Taste or the Ladies Absurdity' (1771). A 1776 article in the Ipswich Journal describes a woman appearing at a masquerade in London's Pantheon in May 1776: "a lady with her head dressed agreeable to Darly's caricature of a head, so enormous, as actually to contain both a plan and model of Boston, and the provincial army on Bunker's Hill. (...) The supper, desert and wines were plentiful and good; but the decorations were rather puerile." This is an obvious reference to the Darly cartoon 'Bunkers Hill or America's Head Dress' (1776).

Likewise, modern audiences may be surprised that many of Darly's cartoons were only slight exaggerations of how people dressed back then. Many men and women applied padding, powder and animal fat to their wigs and cheeks. Some women gave their wigs extensions to the point that they towered above most other people and had difficulty keeping balance. It is not all that surprising that 18th-century audiences were both disgusted and fascinated by these "monstrosities". Especially in England, a country infamous for its eccentric habitants, silly authority figures, looney upperclass and the annual bizarre costume traditions of the Ascot steeplechase races. Another 18th-century prototypical comic artist who ridiculed fashions and haircuts in his cartoons was Hendrik Numan.

Satire on a doctor or an apothecary from around 1759 with speech balloons.

Proto-comics

In 1756, Matthew Darly and George Edwards published a caricature of George Lyttelton, the secretary of the Prince of Wales, which was notable for its use of a speech balloon. Subsequently, other early political cartoons also make use of speech balloons, like 'Caesar at New Market' (1757), 'The Game of Hum' (1762), 'Tit for Tat, or Kiss My A-s is No Treason' (1762), 'An Antidote by Carr, for C-I-d-n Impurities' (1762), 'The Boot & the Block-Head' (1762), 'The Scotch Damien' (1762), 'The Northern Con-Star-Nation, or Wonderful Phoenomoenon' (1762), 'The Elder Women of the City, or the - Kiss My Ar-e Addressers' (1763) and 'England's Scotch Friend' (1763). Most mock Scotland, which England had only recently conquered and made part of the United Kingdom. Matthew Darly made the cartoon 'The Scotch Tent, or True Contrast' (1762), showing two men looking at a kilt-like tent, talking in speech balloons. Mary Darly drew 'The Pedlars, or Scotch Merchants of London, the hum Addresers' (1763), which mocks Scottish pedlars. At the time, these street salesmen were often fined by policemen for disturbing the peace or ripping off clients. Darly draws them as a large crowd, divided in two horizontal rows. Each Scotsman talks in a speech balloon.

From the 1770s on, the Thirteen Colonies in America became another satirical target. Especially when they declared themselves independent in 1776 as the United States. Two cartoons from this period regarding the aftermath of these events use speech balloons. 'The Commissioners' (1778) shows British commissioners negotiating peace by begging at the U.S.'s feet, who is depicted as a proud Native American sitting on all the products they are dependent on. In 'Brittania's Ruin' (1779), Lady Brittannia laments over her political losses, while the USA, France, Spain and the Netherlands are also depicted as people, each describing their political, military and economic plans in speech balloons. Finally, Matthew Darly's 'The Stable Voters of Beer Lane Windsor' (1780) pokes fun at voters by depicting them as horses in a literal stable. The human characters all use speech balloons.

Because of their usage of sequences, the most striking prototypical comics are 'Now and Then' and 'Macaronies Drawn After The Life'. 'Now and Then' (1757) shows three people on the left, symbolizing the present, and three on the right, symbolizing the past. Although there are no panels, the text above these two threesomes separates these two moments in time. The three people "now" represent the city council of Newcastle. The three people "then" are 16th-century people Francis Drake, Francis Walsingham and William Cecil, 1st Baron of Burghley. Their glorious past deeds are contrasted with the incompetence of the current people in power. 'Now and Then' combines a sequence with speech balloons. 'Macaronies Drawn After The Life' (1773) is a pantomime comic, with a much clearer separation between two images. On the left panel, a "macarony" dandy is shown, contrasted with a skeleton in the right panel.

Death and legacy

On 25 January 1780, Matthew Darly passed away. Mary sold their last print in October 1780. In 1781, the shop at number 39 in the Strand neighborhood was taken over by a new owner. What happened to Mary Darly next is shrouded in mystery. It has been suggested that she sold her stock to William and Hannah Humphrey, who indeed reprinted some of the Darly cartoons. Either way the Darlys wrote history. They paved the way for many other print shops in England to sell caricatures and cartoons. Without their pioneer work, legendary British caricaturists of the late 18th century and early 19th century, like James Gillray, Richard Newton, Isaac Cruikshank, Isaac Robert Cruikshank, George Cruikshank, Thomas Rowlandson and William Heath, might never have picked up a pencil...