'The Life of a Soldier' (1823).

William Heath was an early 19th-century Scottish caricaturist and the house cartoonist of the first genuine comic magazine in history, The Glasgow Looking Glass (1825-1826). Heath made several single-panel cartoons, some of which make use of speech balloons. A couple are sequentially illustrated narratives or prototypical text comics, with text captions underneath the images. 'Embarkation. Voyage of a Steam Boat from Glasgow to Liverpool', 'The Morbiade', 'History of a Coat', 'The Life of a Soldier: a Narrative and Descriptive Poem' and 'An Essay on Modern Medical Education' are the first known comics created exclusively for serialization in a comic magazine. Heath is the earliest known comic artist to use the cliffhanger statement: "To Be Continued..." and earliest known Scottish comic artist in history.

Early life and career

William Heath was born in 1794 in Northumberland, in the North East of England, directly bordering with Scotland. While he could be considered English by modern geographical standards, he identified as a Scotsman and his contemporaries did the same. In 1809, at age 14, Heath made his graphic debut. Throughout the next decade, he mostly illustrated military battles, such as 'Attack On The Road To Bayonne' (1813), 'The Battle of Nivelle' (1813), 'The Battle of Morales' (1813), 'The Battle of Roliça' (1815) and 'The Battle of Assaye' (1815). His illustrations were printed in military books or displayed as panorama paintings. When the demand for military illustrations declined in the 1820s, Heath changed his career and became a satirical cartoonist instead.

'A Correct View of the New Machine for Winding Up the Ladies', 1828.

Cartooning

In the 1820s, Heath focused on topical caricatures in the style of his main graphic influence James Gillray. Much like his contemporaries Thomas Rowlandson and George Cruikshank, Heath made many drawings lampooning politicians and fashions. He caricatured King George IV and various British Prime Ministers, but also portrayed well known entertainers, such as clown Joseph Grimaldi and sideshow artists like Zulu woman Saartjie Baartman and the Siamese twin Chang and Eng Bunker. Between 1827 and 1829, Heath used the pseudonym Paul Pry, after a character from John Poole's popular theatrical play 'Paul Pry' (1825). When signing his work, Heath always drew a tiny figure depicting Paul Pry next to his pseudonym. It can usually be seen on the bottom left corner, between the inner and outer frames of his engravings.

'Dr. Arther & His Man Bob Giving John Bull A Bolus' (1829). The cartoon depicts Robert Peel, founder of the British Conservative Party, and fellow party member Arthur Wellesley, better known as the Duke of Wellington, jamming a new constitutional reform down the throat of John Bull, the national personification of Great Britain. The reform in question was the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829.

The Glasgow Looking Glass

Plagued by debts, Heath left London around 1825 and fled to Glasgow. There, he joined lithographic printer Thomas Hopkirk and his print manager John Watson to launch a magazine dedicated entirely to cartoons and caricatures. The first issue of The Glasgow Looking Glass appeared on 11 June 1825. There had been publications that ran caricatures and illustrations before, but usually just as stand-alone drawings. The Comick Magazine, for instance, which first saw light on 1 April 1796, featured mostly written articles. The only cartoons in its pages were reprints of William Hogarth's sequential engravings and paintings, made half a century earlier. The Caricature Magazine, started in 1808, is another contender for the title "earliest comic magazine", because it serialized Thomas Rowlandson's picture story 'Dr. Syntax'. Yet, much like The Comick Magazine, it wasn't devoted to cartoons alone. In that regard, The Glasgow Looking Glass can be named the first genuine comic magazine in history.

The Glasgow Looking Glass featured news and cartoons about national and international politics and society, but also more regional content that would appeal to a Glaswegian demographic. From the sixth issue on (18 August 1825), the magazine broadened its spectrum and changed its name to The Northern Looking Glass. Heath apparently became a regular contributor from the tenth issue on. He always claimed that the magazine was his idea, while in reality Watson was the driving force. It was Watson who suggested using lithographic printing techniques and initiating the name change to The Northern Looking Glass.

For all of its historical value, The Glasgow Looking Glass didn't sell well. Hardly a year after its first issue, the title already folded. The seventeenth and final issue hit the market on 3 April 1826. Two extra issues were produced by Richard Griffin & Co. afterwards, but these were merely a death gasp. In June 1826, after 19 issues, the magazine folded for good. A compilation book was published a year later, titled 'A Selection of Humorous Engravings, Caricatures &c. by Various Artists, Selected and Arranged by Thomas McLean'. In 1830, William Heath and publisher Thomas McLean revived The Northern Looking Glass, albeit under a different title: McLean's Monthly Sheet of Caricatures, or, The Looking Glass. The paper now aimed at a more upper class demographic and ran on a monthly schedule. It lasted 60 issues, until its final issue hit the market on 1 December 1834.

'Monster Soup' (1828): A woman looks in a cup of water scooped from the Thames. It’s a literal "monster soup", because the drinking water is so contaminated and toxic.

Embarkation / The Morbiade

In the second issue of The Glasgow Looking Glass (25 June 1825), Heath launched two picture stories, serialized in the next issues. 'Embarkation. Voyage of a Steam Boat from Glasgow to Liverpool', offers a look at passengers during a sea voyage. It ran up until the seventh issue (3 September 1825). The other serialized story in the second issue, 'The Morbiade', is a two-parter about a riot and the mayhem it causes. It was concluded in issue #3 of 9 July 1825. 'Embarkation' is notable as an early example of self-reflexive comedy in comics. In the first episode, a man on board of the ship reads an issue of The Glasgow Looking Glass. Both 'Embarkation' and 'The Morbiade' are the first known examples of serialized comics created exclusively for a magazine. They also mark the first use of the cliffhanger line "To be continued..." at the end of a comic page.

History Of A Coat

In issue #4 of The Glasgow Looking Glass (23 July 1825), 'History Of A Coat', was published. This serialized picture story is notable for using an inanimate object as a protagonist, instead of a human or animal. In that regard, it almost feels like a parody of earlier "rise and fall" picture stories about people. Here, the plot revolves around a coat which moves from owner to owner. It starts off as wool, manufactured by, respectively, a shepherd, weaver and tailor into a piece of clothing. The coat is bought by a dandy, who later gives it to a foreign valet. The garment keeps changing owners, being handed out, resold and worn until it's so ravished that only a beggar values it. The coat eventually ends up as part of a scarecrow, until hungry pigs guzzle up its remains. In later centuries, other cartoonists have also made comics based on a simple object moving from owner to owner, among them Ed Carey's 'Adventure of a Bad Half Dollar' (1909-1910) and Frank King's 'That Phoney Nickel' (1930-1933).

An Essay on Modern Medical Education

Another notable picture story by Heath in The Northern Looking Glass was 'An Essay on Modern Medical Education' (published in issues #6, #8 and #9, on 18 August, 3 September and 17 September 1825). In 10 successive illustrations, Heath depicts life at university, where medical students are more interested in having fun and drinking, than taking their studies and teachers seriously. Some of the images are quite gruesome. The young men dig up corpses to use for medical practice and experiment on live animals. In one scene, a man's leg is amputated without anaesthetic. In another, wounded soldiers on the battlefield are stitched back together, complete with one whose chopped off head is put back on his body. Heath's story is satirical, with lots of cartoony exaggerations. For instance, walking skeletons inspect the hospitals, while the students keep coffins nearby in case their unfortunate patients won't make it.

The Life Of a Soldier

For the eighth issue of The Northern Looking Glass (17 September 1825), Heath drew another picture story, 'The Life Of a Soldier, a Narrative and Descriptive Poem', which was clearly influenced by Thomas Rowlandson's 'The Adventures of Johnny Newcome in the Navy' (1818). It follows the adventures of a soldier who is recruited in the army. Contrary to Heath's previous serialized comics, 'The Life Of A Soldier' appeared on a more irregular basis. In some issues, no episodes can be found. The story was eventually concluded in issue #16 (20 February 1826). In the same issue, Heath launched a similar narrative, 'Life Of a Sailor', but this never received a follow-up, because the magazine was discontinued shortly afterwards. Given Heath's increasing problems with alcoholism and bringing in his finished work on time, it could explain why his production slowed down.

'Essay on Modern Medical Education' (1825).

Prototypical comics from 1828-1829

Some of Heath's later one-panel cartoons are notable for their use of speech balloons. 'We Have The Exhibition To Examine … Ah If One Could But See’ (1828) shows a group of people at a gallery. Most of the women wear preposterously large hats, causing a man to complain that he barely saw any of the exhibited paintings, because his view was obscured by the women's bonnets. All dialogue is depicted in speech balloons. Another one-panel cartoon, 'Dr. Arther & His Man Bob Giving John Bull A Bolus' (1829), features politicians Robert Peel and Prime Minister Arthur Wellesley (AKA the Duke of Wellington) in the presence of national personification John Bull. Again, speech balloons are used, while the two politicians cram the Catholic Emancipation Act through John Bull's throat. Heath's 'Theatrical Characters in Ten Plates' (1829) is another notable sequential illustrated narrative, which depicts ten British politicians in the guise of various characters from theatrical plays. George IV is, for instance, depicted as a manager, while his mistress Lady Conyngham is lampooned as an obese prima donna. The etchings were printed in 1829 by Thomas McLean.

'March of Intellect' (1829), an interesting vision of what the future will be like thanks to advanced technology.

Final years and death

Throughout his life, William Heath suffered from alcoholism. He spent too much time in pubs, which not only left him in debts, but also made him miss his deadlines. Even when his cartoons did get printed, not all readers appreciated them. At times they were so biting that The Glasgow Looking Glass/Northern Looking Glass actually lost readers over them. When the magazine was discontinued in April 1826, Heath moved back to London in the following month. When in 1830, the title returned as McLean's Monthly Sheet of Caricatures, or, The Looking Glass, Heath was rehired as house cartoonist. However, his drinking problems and unreliability became too problematic. After seven issues, he was fired and replaced by Robert Seymour. His career never recovered. William Heath died in 1840 at age 45 or 46, in Hampstead, London.

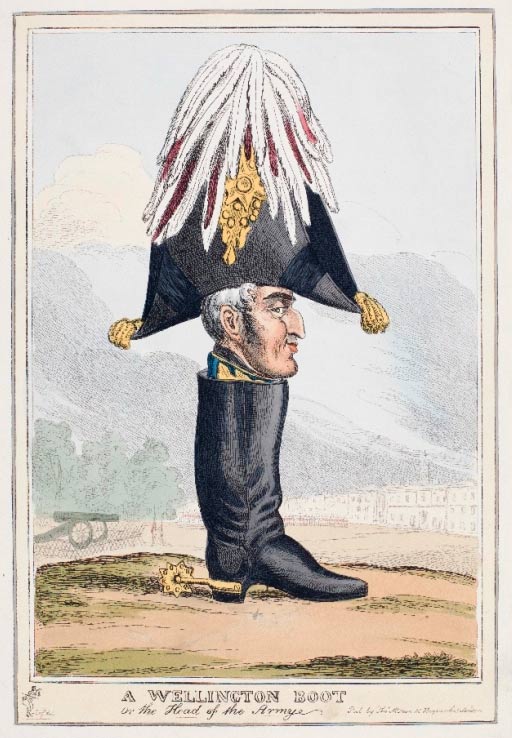

'A Wellington Boot, or the Head of the Army' (1827). It depicts Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, as a literal "Wellington Boot".