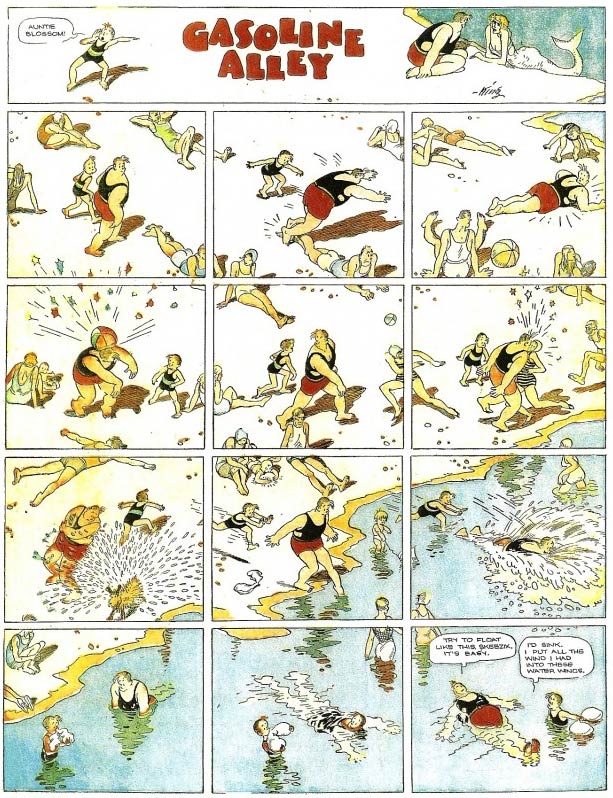

'Gasoline Alley' (30 November 1930).

Frank King was an American newspaper comic artist, most famous for his signature series 'Gasoline Alley' (1918- ), which is the second-longest running comic strip in the world, only behind Rudolph Dirks' 'Der Katzenjammer Kids' (1897-2006). Contrary to the latter series it is still in syndication today (2024), bound to possibly break its record by 2027. 'Gasoline Alley' is the epitome of a comic strip family saga. It has followed the daily antics of its protagonists Walt and Skeezix for over a whole century now. 'Gasoline Alley' has always moved along with the times by having its characters age. By now, the original characters have four generations worth of children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren and a revolving door-cast of new people moving in and out their neighborhood. 'Gasoline Alley' is a slice-of-life comic strip, based on recognizable everyday events in a quiet, domestic setting. Together with Chic Jackson's 'Roger Bean' (1913-1934), it was the first soap opera in the world, long before radio and TV created their own long-running soaps. But the comic strip has more to offer than mundane events. King provided a heartwarming family dynamic which has moved readers for

decades. And even within his conformist setting, he still experimented with visually interesting lay-outs, coloring and audacious breaks in graphic style. Some of his Sunday pages are less story-based and instead offer poetic atmosphere. In no other art form, also beyond the world of comics, has there ever been a work that expressed so much humanity over the course of a full century.

Early life

Frank Oscar King was born in 1883 in Cashton, a small town in the Kickapoo Hills of Wisconsin, but moved to Tomah in the same state when he was two years old. His father was a mechanic and by the time King grew into adulthood, he followed in his footsteps. But he also showed a talent for drawing. In an interview with the Chicago Tribune, dated 24 March 1948 and conducted by Joseph Hearst, King reflected: "I've been drawing one thing or another ever since I was three years old and practiced on the wallpaper at home. In high school I used to adorn the edge of my examination papers with little cartoons. I wasn't trying to show off, but I figured it would distract the teacher's attention and she wouldn't check my answers too closely. Worked, too, because I got through school all right."

Editorial illustration for the Chicago Tribune around 1910, already showing the artist's fascination with depicting everyday life.

Early cartooning career

While entering country fair drawing competitions, King's skills were noticed by a traveling salesman who brought him in touch with the editor of The Minneapolis Times. Starting in 1901, he worked as a cartoonist there. The young man provided lay-outs, made courtroom sketches and retouched certain photographs. Between 1905 and 1906, King moved to Chicago where he studied art at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts. He illustrated ads for an advertising agency and became a cartoonist for The Chicago American, The Chicago Examiner and, from 1909 on, The Chicago Tribune. There, he worked alongside cartoonist Clare Briggs, who became a large artistic influence on King's work.

King's first daily comic strip was 'Jonah, a Whale for Trouble', which ran in The Chicago Tribune from 3 October until 8 December 1910. He then joined the paper's Sunday comics section with features like 'Oh Augustus' (28 August 1910 - 3 September 1911), 'Honest Harold, Do You Mean What You Say?' (2 October 1910 - 6 October 1912), 'Young Teddy' (10 September 1911 - 6 October 1912) and 'Look Out For Motorcycle Mike' (10 September 1911 - 18 January 1914). King was also contributing to the Tribune's collective feature 'Foolish Limericks' (1910-1911), originally created by A.D.Reed. In 1911 and 1912, he did a weekly feature called 'Optimistic Buggs'.

'Look Out For Motorcycle Mike!'.

Hi-Hopper

Between 1 February and 27 December 1914, King created the comic strip 'Hi-Hopper', about an anthropomorphic frog. Between April and June of that year, 'Hi-Hopper' was part of the Sunday comic "jam" page 'Crazy Quilt'. This full page Sunday feature combined a batch of the Tribune one-tier Sunday strips along with panels and new features in sort of a pinwheel design where each creator did their own strip and some incidental art to come up with a combined full page design.

The Rectangle

When 'Hi-Hopper' ended, The Chicago Tribune introduced a comics and cartoon section which had been running in its pages for a while, but hadn't received a proper title until that point: The Rectangle. King's one-panel cartoons and comic features were all published in The Rectangle. It featured lesser known series by his hand, such as 'The Boy Animal Trainer' and 'Here Comes Motorcycle Mike', the latter an early anticipation of the superhero genre. Most other cartoons went by titles such as 'Science Facts', 'Pet Peeves', 'A.W.O.L.', 'It Isn't the Cost, It's the Upkeep' and were just made up as they went along.

Bobby Make-Believe

King's first genuine hit was 'Bobby Make-Believe' (not to be confused with Harry E. Homan 's 1930s comic strip 'Billy Make-Believe), of which the first episode was launched on 31 January 1915. The comic strip featured a young boy, Bobby, who spent his time daydreaming about being a heroic knight, pirate, cowboy, explorer, soldier, etc., etc... Much like Winsor McCay's work – by which it was obviously influenced – the comic strip offered King the opportunity to change thematic scenery and storylines whenever he was tired of the previous one. The series ran until 1919, but was revived for a few months in 1940, albeit in reprints. 'Bobby Make-Believe' was additionally significant for featuring the character of Rachel, an African-American housemaid, who was actually his first recurring character. She was based on a similar person with the same name King met while in college. King would later re-use her as a principal cast member in 'Gasoline Alley'.

First 'Gasoline Alley' appearance in the Rectangle section of 24 November 1918.

Gasoline Alley

During the First World War, King was sent to Europe, where he drew propaganda cartoons and illustrations which were sent back to the United States to be published in their newspapers. On 11 November 1918, the war was over and King returned to his home country, where, on 24 November, he created the first episode of 'Gasoline Alley', originally titled 'Sunday Morning in Gasoline Alley'. The comic strip was originally based on a thin theme: characters who were busy in their garage and discussed automobiles. King often spent his Sundays the same way, meeting his brother and other car owners in their local alley. Since many American readers shared similar Sunday rituals, 'Gasoline Alley' quickly caught on. Like all of King's early comics it was originally published in The Rectangle supplement, but on 25 August 1919 it was moved out of these pages to become a daily newspaper comic. By 8 February 1920, The Rectangle was removed from papers and King dropped all his other comics to fully focus on his hit series.

'Gasoline Alley' (16 April 1921).

'Gasoline Alley' was originally the name of the garage business featured in the comic, but as the series expanded, it referred to the town where the protagonists lived. At first, there was no focus on specific characters. Walt Wallet, who was named on 15 December 1918, would become the major protagonist only a year later, on 22 December 1919. He is the owner of the furniture company "Wicker and Wallet" and, just like his spiritual father, he once fought in World War I. King based the character on his own brother-in-law. Walt often has a chat with his neighbors Bill, Avery and Doc Smartley. Bill took his name from King's friend Bill Gannon, while a local doctor in Tomah was the inspiration for Doc. Over the course of the decades, King would introduce many other recurring characters, often based on people he knew in real life, like banker Mr. Engray, based on banker N. Ray Carroll. The rich and miserly businessman Uriah Pert was by far the only real antagonist of the series. Much like Ebenezer Scrooge, he was a genuine nuisance and cold-hearted person. Eventually, King gave Uriah a nephew, Wilmer Bobbie, who is active as a senator. Corrupt to the bone, he made Uriah look more sympathetic and eventually became the new antagonist of the series.

While 'Gasoline Alley' was well liked by male readers, women didn't care much for a comic strip where the characters yakked about cars. At the strong insistence of his editor, King introduced a baby in the series. It was a rather forced move, since Walt was a bachelor and didn't even have a love interest at the time. So a classic comic strip narrative was used instead. On 14 February 1921, Walt found an abandoned baby on his doorstep, which he adopted and named "Skeezix". The name was cowboy slang for a "motherless calf". Later in the series, Walt would eventually find the right woman, Phyllis Blossom, and marry her on 24 June 1926. Their natural-born son, Corky, was introduced on 2 May 1928. Times were more prudent back then and the very idea that comic characters had children (and thus must have had sexual intercourse) disturbed many readers. Usually child characters in series were adopted orphans or nephews of the protagonist. Corky may very well be one of the first comic characters who was neither of these, causing many angry readers' letters at the time. On 28 February 1935, Walt discovered another baby, left behind in his car, which he adopted as well and named Judy.

Walt finds Skeezix on his doorstep on 14 February 1921.

Between soap opera and family saga

Over the course of his century-long run, 'Gasoline Alley' would become one of the earliest soap operas. Not just in comics, but in any genre. Readers could follow the daily antics of Walt, Skeezix and his local small town community for decades. While not the first family comic in history, it's certainly the most iconic, paving the way for similar comics in the genre. Yet few have had the audacity to let the characters age along. Over the years, long-time readers saw Walt's children grow into teenagers, adults, get married, have children and eventually even grand children. Some characters even died off. Walt himself also grew into a senior citizen.

The only other US newspaper comic strips before 'Gasoline Alley' to let their characters age have been Winsor McCay's 'The Story of Hungry Henrietta' (1905) and Chic Jackson's 'Roger Bean' (which was a huge inspiration to 'Gasoline Alley', 1913-1934) and R.M. Brinkerhoff's 'Little Mary Mix-Up' (1917-1957). Afterwards, the also still-running 'Prince Valiant' (1929) by Hal Foster, Milton Caniff's 'Terry and the Pirates' (1934-1946), Jack Dunkley's 'The Larks' (1957-1985), Garry Trudeau's 'Doonesbury' (1968), Tom Batiuk's 'Funky Winterbean' (1972), Lynn Johnston's 'For Better or For Worse' (1979), Robb Armstrong's 'Jump Start' (1989), Rick Kirkman and Jerry Scott's 'Baby Blues' (1990) have also used this rare storytelling device.

'Gasoline Alley' daily from 1922.

The aforementioned Rachel from King's previous newspaper comic 'Bobby Make-Believe' was reintroduced in 'Gasoline Alley' to become a nanny for Skeezix. While still a stereotypical "Mammy" character, Rachel is interesting since she is often portrayed being more knowledgeable about raising children than Walt. Despite being a maid, she doesn't hesitate to speak up for herself. Even more astonishing is the fact that King actually gave her just as much background as all his other cast members. In some episodes, she is actually shown having a private life too. In one narrative, Walt and his wife hire a white maid who bosses Rachel around, causing her to quit. But she is instantly rehired when the couple realizes their mistake. Quite remarkably, both the Chicago Defender and New York Amsterdam News, which aimed at an African-American readership praised Rachel as a positive role model for the black population.

'Gasoline Alley" daily from 1925.

In the 1920s and 1930s, readers could follow Walt and Skeezix' touching father-son relationship, even though the kid always referred to him as "Uncle Walt" (yes, long before Walt Disney received that nickname!). Walt nursed Skeezix when he fell ill with scarlet fever. The boy often had trouble at school and in high school fell in love with a girl: Nina Clock. King never went political, but did write current events into his narratives. When the United States entered World War II in 1941, Skeezix enlisted in the U.S. Army on 16 January 1942, asking Nina to marry him. First, the young man served his country for two years, meeting new friends, Sarge and Hack, among the recruits. After returning to civilian life, both would work in Skeezix' neighborhood gas station. On 28 June 1944, the wedding between Skeezix and Nina took place, which led to the birth of a son, Chipper, on 1 April 1945. Two decades later, Chipper would be drafted during the Vietnam War.

The couple also had a daughter, Clovia, born on 15 May 1949, who married Slim Skinner on 31 May 1977. Clovia and Slim would adopt two neglected children, the boy Rover Bump (1 December 1983) and girl Gretchen (13 April 1978) Hoogy Boogle. They too would eventually have a son, Boog Skinner, who debuted on 8 September 2004, and a daughter Aubee Rose, who was introduced on 10 September 2016. Meanwhile, Walt and Phyllis' natural son, Corky, married Hope Hassel on 1 October 1949. They would have a son, Adam on 21 April 1960, who'd marry Teeka Tok on 26 November 1986 and with whom he'd have a daughter, Ada, born on 8 August 1988. Adam and Teeka also adopted a girl, Amanda Lynn. Walt's adopted daughter Judy grew up to marry Gideon Grubb on 4 May 1961. Their son, Gabriel, was born on 27 June 1966.

Walt gets full custody of Skeezix in this 1927 'Gasoline Alley' daily.

A mirror of daily life

'Gasoline Alley' remains comics' best example of an iconic family saga. Nearly four generations of Walt's descendants have been created now. Many work in Skeezix' garage, while others are just frequent passers-by. With such a huge and ever-expanding cast, 'Gasoline Alley' could easily focus on different characters and storylines, allowing for a lot of variation despite always being set in Walt's hometown and being relatively low-key in content. Right from the start, 'Gasoline Alley' stood out among other newspaper comics by never featuring zany slapstick, off-the-wall characters or heavy-handed tragedies. This has sometimes been a criticism too. Some observers claimed that the comic is too mundane, featuring no real memorable characters and nothing ever out-of-the-ordinary happening.

The appeal of 'Gasoline Alley' mostly stems from its recognizability. A small and quiet suburban neighborhood in everytown USA, where local people conduct their everyday business. King's comic strip was rarely about a punchline. Most of the time, his characters are just chatting. In some episodes, King made a huge drawing of a typical Sunday afternoon, where the men chat about cars, their women talk about their family lives and children play outside. All their speech balloons are shown in one picture and the reader can catch fragments of their conversations, none of the dialogues more or less important than the other. Walt and his ever-growing family and circle of friends often discuss work, school, shopping, raising children and hobbies. In a sense, it was a reality series decades before the term existed.

The world of 'Gasoline Alley' is so comfortable and inviting that many readers are instantly hooked on it. King was a remarkable observer of the human condition. His characters were never caricatures, but believable people of flesh and blood. For an artist working in a genre so commonly associated with cartoony exaggeration, it is an incredible achievement that King still kept readers' interest alive. The artist strove for naturalism by talking with many people of different professions to get a good impression of their daily lives. He also studied photographs of many everyday streets and objects.

In a 4 June 2010 interview, conducted by Chris Mautner for the website www.cbr.com, comic critic Jeet Heer pointed out that 'Gasoline Alley' is more focused than most newspaper comics, who tend to have a "jagged start-and-stop feeling because they were geared for daily consumption. Gasoline Alley does read like a long, leisurely novel." While the dailies follow a storyline, the Sunday episodes, first launched on 24 October 1920, tend to be more their own separate entity. Usually it features Walt and/or Skeezix going out for a walk or a trip, while they ponder over nature or life itself. The Sundays are often seen as King at his most poetic and philosophical.

'Gasoline Alley" (30 November 1931).

Graphic experimentation

For such a cozy family comic, the Sunday episodes of 'Gasoline Alley' frequently feature bold graphic experiments. King enjoyed treating a full page as if it was a single scene, despite still dividing it into panels. Many of these pages toy around with lay-out, design and color. In a 2 December 1928 Sunday page, most of the characters are depicted in silhouette. A famous gag from 24 August 1930, shows Walt and Skeezix at the beach. The entire page is one large drawing, divided by 12 panels, with all action shown from a bird-eye's perspective. All Walt and Skeezix do is move through the sunbathing crowd to reach the sea and take a swim. Another episode from 19 August 1934 has Skeezix look at himself in the reflection of a river, imagining himself floating through this upside down world.

One of 'Gasoline Alley' 's recurring traditions were Walt and Skeezix' annual walks in the woods during the fall. These Sunday pages always provided King with an opportunity to play around with different background designs. In a 2 November 1930 episode, for instance, father and son suddenly find themselves in a Cubist-Fauvist world, right out of a Pablo Picasso painting. A few days later, on 30 November, the autumn backgrounds look like woodcut panels by Frans Masereel, Otto Nückel or Lynd Ward. A year later, on 30 November 1931, Walt and Skeezix use a compass, which leads to a series of colorful geometric patterns in the background.

In episodes like these, Walt and Skeezix are just observers of magnificent displays of King's creative designs. Plot has no importance, except to provide the reader with a poetic atmosphere, reflecting a joy and wonder about life. Any criticism that 'Gasoline Alley' was just a formulaic series without any interesting developments is contradicted by these Sunday pages. Few other early 20th-century newspaper comic artists had the ambition, nor the audacity, to create such remarkable breaks in style.

'Gasoline Alley' (24 August 1930).

Success

'Gasoline Alley' soon appeared in over 300 daily newspapers, distributed by Tribune Media Services. Its gentle style appealed to young and old. General audiences enjoyed it, while more sophisticated readers also preferred it to the more broad and one-dimensional gag comics in vogue at the time. When many of these comics went out of fashion, 'Gasoline Alley' remained in print. Readers were always curious to know whatever happened next in the characters' lives. King became so rich that he bought his own estate in Lake Tohopekaliga, Florida. He spent most of his spare time painting and sculpting, rarely bothered by anyone because he didn't even own a telephone. Today, his artwork can be seen at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum in Columbus, Ohio.

Media adaptations

Since 'Gasoline Alley' was basically the godfather of all soap operas, it came to no surprise that its format inspired a radio sitcom, 'Uncle Walt and Skeezix' (1931-1949), which aired on NBC for nearly two decades, albeit with irregular intervals. In 1941, it was renamed 'Gasoline Alley' and actually provided an audio re-enactment of the gag appearing in the newspapers the very same morning. In 1951, the comic strip was also adapted into two live-action comedy films, 'Gasoline Alley' (1951) and 'Corky of Gasoline Alley' (1951).

'Gasoline Alley' daily from 1929.

Parody

'Gasoline Alley' was such a newspaper mainstay that it eventually ended up being spoofed in Mad Magazine too. In issue #15 (September 1954), Harvey Kurtzman and Will Elder lampooned it as 'Gasoline Valley'. The aging in the comic is sped up to ridiculous speeds, with Skeezix growing taller and more adult in every panel. Every time the boy returns home he finds out that Walt and Phyllis have found yet another baby on their doorstep. As Skeezix grows into adulthood within a few panels, he suddenly finds out that basically everybody is aging rapidly, to the point that he becomes his own grandfather and his parents his children. During the 1930s, King's characters were also used in some Tijuana Bibles, mini-comics in which various comic characters were illegally depicted in pornographic activities.

Companion comic strips

Between 14 December and 17 September 1933, King also drew a topper strip, accompanying the 'Gasoline Alley' Sunday comic. Titled 'That Phoney Nickel' (1930-1933), it followed a coin moving from owner to owner. The idea of making a comic strip about an object moving from owner to owner had been done earlier by William Heath's 'History Of A Coat' (1825) and Ed Carey's 'Adventure of a Bad Half Dollar' (1909-1910). Between February and September, the 'Gasoline Alley' Sunday comics were additionally complemented with the 'Puny Puns' topper panel. Starting in 1935, the Sunday comic's topper space was filled with spin-off strips from the 'Gasoline Alley' feature, successively 'Corky' (18 August 1935-1945) and 'Wilmer's Little Brother Hugo' (1944-1973). While still credited to King, artwork for these Sunday features was handled largely by the cartoonist's assistant Bill Perry.

Frank King with Bill Perry and Val Heinz.

Assistance and 'Gasoline Alley' after King's retirement

According to legend, King once boasted that he could teach any amateur to draw. As part of a bet with a few of his colleagues he picked out the mailroom delivery boy, Bill Perry, to be trained as his assistant in 1925. By 1926 Perry became his full-time assistant. Yet King actually cheated: Perry was already an assistant to Carl Ed's 'Harold Teen' comic and thus hardly as "untrained" as King claimed. Between 1945 and 1949, King was also assisted by Val Heinz and between 1950 and 1963 by Bob Zschiesche. Other artists who ghosted on the series over time were Sals Bostwick, John Chase, Albert Tolf and Jack Fox (who later went on to assist Ed Dodd on 'Mark Trail').

On 29 April 1951, King left the Sunday pages in the safe hands of Bill Perry. King kept drawing the daily episodes of 'Gasoline Alley' until 1956, after which he received assistance from Dick Moores. While Moores slowly but surely got more involved, King could eventually permanently retire in 1959. Moores took the comic strip into a different direction, adapting it to the changing times. He modernized the setting and introduced new characters who became the more primary focus, such as Rufus the handyman and Joel the junkman, Rufus' criminal brother Magnus and the female mayor Miss Melba. This kept the series fresh and popular, even when King passed away in 1969. Curiously, Moores made the decision to not let the characters age anymore.

After the death of its spiritual creator, 'Gasoline Alley' continued its long run. Perry kept drawing the Sunday pages until 28 September 1975, after which Moores took these over as well. However, to avoid doing everything alone, Moores rehired Zschiesche again as assistant, bringing in another assistant from 1978 on: Jim Scancarelli. Moores felt that Scancarelli handled deadlines better and thus Zschiesche was let go on 6 April 1980. When Moores passed away in 1986, Scancarelli continued the series, which he still does as of today (2024). Scancarelli further modernized the setting along with the times and expanded the cast. He also made the decision to have the characters age again. This led to the death of Walt's beloved wife Phyllis on 26 April 2004. It allowed for new storylines about Walt's life as a widower.

Recognition

In 1949, Frank King won the Silver T-Square Award, followed by the Humor Comic Strip Award in 1957. In 1958, the artist won a Reuben Award. Dick Moores also received the same honor for the same series in 1974. In 1995, 'Gasoline Alley' was honored with a U.S. postage stamp. A highway in Florida, King's Highway, was named after Frank King.

Personal life and death

Contrary to his pen-and-ink creations, King's own family life was less idyllic. His wife Delia's first pregnancy in 1913 ended in stillbirth. When a new son, Robert Drew, was born in 1916, King nicknamed him "Skeezix", the name he later used for his 'Gasoline Alley' character. But his real-life son was sent off to boarding school as often as possible. In his diaries, Robert King complained that he only saw his parents during the summer, when boarding school was closed. He remembered them as emotionally distant, in sharp contrast with how loving the bond between Walt and his own offspring was. According to comic historian Jeet Heer, 'Gasoline Alley' was in many ways an expression of the sort of family life Frank King actually wished he could have himself, but never had.

After his retirement in 1959, King lived for another decade. He passed away in 1969, in his home in Winter Park, Florida, at age 86.

Cultural influence

A garage area at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway has been named 'Gasoline Alley'. British pop musician Rod Stewart named his second solo album and its title track 'Gasoline Alley' (1970). The same year, the U.S. band Blue Mink released a single named 'Gasoline Alley Bred' (1970), which was covered that same year by the British rock band The Hollies, who are famous for their other hit cover 'He Ain't Heavy, He's My Brother' (1969). A local radio show in Indianapolis, hosted by Donald Davidson and originally named 'Dial Davidson' (1966), was renamed 'The Talk of Gasoline Alley' by the late 1970s.

Legacy and influence

Frank King enjoyed a rare honor for any comic artist: creating a comic strip that has kept running for over a century now, long after the original creator passed away. To newspaper readers, there is something comforting about the fact that the daily antics of Walt, Skeezix and their ever-expanding neighborhood and family have entertained people for over 100 continuous years. 'Gasoline Alley' feels less like a comic strip, more like an illustrated diary, following four generations of family members during their trials and tribulations. A time capsule of a century worth of changes in technology and society, with prime focus on everyday domestic life. Historians could devote an entire essay or book about the topic. Particularly since no cultural work has ever managed to go on for so long, day in, day out. Even the aforementioned far older 'Katzenjammer Kids' (1897-2006) by Rudolph Dirks and the third-longest continuous comic strip of all time, Billy DeBeck's 'Barney Google and Snuffy Smith' (1919- ) are basically straightforward gag comics, lacking the historic value and humanity that 'Gasoline Alley' has expressed for over 10 decades.

Though it must be said that these 10 decades worth of daily episodes have never been made available in their entirety. It's also an impossible task, seeing that many old episodes are seemingly lost. Spec Productions managed to bring together four volumes, spanning all episodes between 1918 and 1920. Drawn & Quarterly made another attempt in 2005, so far managing to secure all episodes until 1932. This particular collection, dubbed 'Walt and Skeezix', was designed by Chris Ware and introductions by Canadian comics critic Jeet Heer. A labor of love, it also brings together many never-before-seen photographs, letters, diary entries and newspaper clippings by King's granddaughter Drewanna. In 2014, Dark Horse Comics collected all Sunday episodes between 1920 and 1925 in two hardback volumes. In 2023, Sunday Press released 'Crazy Quilt: Scraps and Panels on the Way to Gasoline Alley', a collection of Frank King's work before 'Gasoline Alley', edited by Peter Maresca.

Frank King was an influence on Seth, Chester Brown, Peter & Maria Hoey, Chris Ware and Joe Matt. Matt's personal collections of original 'Gasoline Alley' episodes have been a great aid in providing a complete collection of seemingly lost entries in the series. Ware once described 'Gasoline Alley' and particularly King's narratives as "(...) something that tried to capture the texture and feeling of life as it slowly, inextricably, and hopelessly passed by."