Publicity drawing of 'Mickey Mouse'.

Walt Disney's name is synonymous with animation. He and his studio transformed this branch of film to a dazzling level, which is still the standard all cartoons are judged by until this day. Yet Disney produced more than cartoons alone: he ventured into live-action films, nature documentaries, TV shows, theme parks, merchandising and comics. His company is the biggest entertainment enterprise on Earth. Disney takes up a special place in the history of comics, although he only created one comic strip himself, the unpublished 'Mr. George's Wife' (1920). After 1926, he never made another published drawing again. He wrote a few early episodes of the very first comic strip based on his signature character 'Mickey Mouse', but had nothing to do with any other Disney comics. And yet Mickey, Donald Duck and Goofy are nowadays the most recognizable fictional characters in the world. Arguably, Disney is the only cartoonist to be just as famous as his characters. A global network of writers, artists and publishers have produced countless comics based on his films and TV series, sometimes creating new characters exclusive to the comics themselves (see our separate listing). In terms of employment, more artists have worked for Disney than any other cartoon studio, either directly or through licensees. Disney is widely admired for creating charming quality family entertainment. A century of generations share fond childhood memories of his work. All of his products, including his comics, are marked by tight quality control. And yet, he and his company haven't been spared from criticism. Accusations of commercialisation, Americanisation, kitsch, bowdlerizing literary classics and fighting unfair copyright battles remain rampant. But, for better or worse, The Walt Disney Company remains the most omnipresent cultural force on our planet.

Artwork inspired by Carey Orr for the McKinley High School newspaper, The Voice (© Disney).

Early years and influences

Walter Elias Disney was born in 1901 in Chicago as the son of a farmer. At age four, his family moved to Marceline, Missouri. The boy had fond memories of rural America, barnyard animals and the railway track next to his house, imagery he would evoke time and time again in his work. As a child, he absorbed many novels illustrated by artists like John Bauer, Wilhelm Busch, Gustave Doré, Edmund Dulac, J.J. Grandville, Theodor Kittelsen, Beatrix Potter, Arthur Rackham, Gustaf Tenggren and John Tenniel, to name a few. Later in his career Disney let his artists take inspiration from classic European painters, particularly the Romantic movement. In the field of comics, Disney admired Bud Fisher, George Herriman, Winsor McCay, George McManus, Clifton Meek, Carey Orr, Richard F. Outcault, Carl Emil Schultze, T.S. Sullivant and Ryan Walker. In 1942, he even let one of his artists, Floyd Gottfredson, create a special birthday drawing for publisher William Randolph Hearst, whose newspapers featured some of the finest comics of their day. In terms of cinema, Disney closely observed Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd, Fritz Lang, Benjamin Christensen and F.W. Murnau, alongside animation pioneers like Winsor McCay, Max and Dave Fleischer's 'Koko the Clown' and Pat Sullivan and Otto Messmer's 'Felix the Cat'.

'Mr. George's Wife', comic strip by Walt Disney, around 1920 (© Disney).

Personal comics

In 1911, when Disney was 10 years old, his parents moved to Kansas City, where his father started a newspaper delivery route. Walt and his brother Roy had to wake up early to deliver morning papers before they went to school. They kept this exhausting ordeal up for six years. In between, Walt drew cartoons for his school paper at McKinley High School, Chicago, and later on, studied drawing at the Kansas City Art Institute and Chicago Academy of Fine Arts.

In 1917, the United States got involved with the First World War. Walt Disney was too young to be drafted, so he forged his birth certificate. He served in France as a Red Cross ambulance driver, but saw no military action. In his spare time, he drew cartoons for the army magazine Stars and Stripes. His first known published artwork appeared in a scrapbook handed out by the Chicago Public Library to families of First World War servicemen. The book, titled 'A Scrap Book Made For Our Soldiers and Sailors by Citizens of Chicago and The Chicago Public Library' (1918), not only included soldiers and the German Kaiser, but also the first two rodents in Disney's oeuvre. Back in his home country, Disney applied for a job as cartoonist at the magazines Life and Judge. He drew a try-out comic strip, 'Mr. George's Wife' (1920), but all his efforts got rejected, which made his interest shift to another medium: animation.

The original Alice was portrayed by Virginia Davis, a child actor from Kansas. Later Alice films starred Margie Gay as the title character (© Disney).

Early animation career

In the 1920s, animation was still crude filler material for movie theaters. A mere novelty to most, Disney saw potential in the medium. Between 1919 and 1920, he worked as an advertising artist at Pesmen-Rubin Commercial Art Studio, where he met the talented Ub Iwerks. They decided to create their own studio, specializing in advertising cartoons. Unfortunately, they went bankrupt within a month. In 1921, the young men improved their skills at the Kansas City Film Ad Company. Afterwards, they set up The Laugh-O-Gram Studio, which had Marion T. Ross, Fred Harman, Hugh Harman, Rudolf Ising and Friz Freleng among their early employees. The 'Laugh-O Gram' cartoons initially focused on modernized fairy tales, screened in the local Kansas City cinema theaters owned by Frank L. Newman. When they failed to make a profit, Walt's brother, Roy Disney, stepped in. Thanks to his keen business sense, the company managed to remain stable. He stayed Disney's business manager for the rest of their respective careers. Walt himself gave up drawing and became a full-time creative advisor and movie producer.

The Laugh-O-Gram Studio produced a series which combined live-action with animation: the 'Alice Comedies' (1923-1927). It marked Disney's first humble success. The shorts also introduced the oldest recurring Disney character, Peg-Leg Pete, who later became Mickey Mouse's nemesis.

Title card for a Laugh-O-Gram cartoon (1922) (© Disney).

Oswald the Lucky Rabbit

After five years, Disney decided to end his popular 'Alice Comedies' series in favor of something new. In 1927, he secured a distribution deal between his animation studio Laugh-O-Gram and Universal Pictures. He let his best animator, Ub Iwerks, design a new character, Oswald the Lucky Rabbit (1927). The 'Oswald' series was popular, but Disney couldn't cash in on this success, because his producer Charles Mintz owned the rights. Some sources claim that Disney was surprised to find this out, but in reality he knew very well what was in their contract. His real shock was that behind his back, Mintz bought out nearly his entire studio, leaving him behind with only nine loyal employees, namely Iwerks, Les Clark, Johnny Cannon and six inkers and painters (one of them Disney's future wife, Lilian Bounds). Mintz continued producing 'Oswald' cartoons on his own, later selling the rights to Walter Lantz, who continued the series until 1943, but the films were never quite as popular again.

In 1935, National Periodicals (DC) launched a comic book featuring Oswald the Rabbit, drawn by Al Stahl for the New Fun comic books. In 1942, Dell Comics relaunched 'Oswald' comics with writer John Stanley and artists like Dan Gormley, Dan Noonan, Lloyd White and Jack Bradbury. Oswald now received two adopted children, Floyd and Lloyd, to create stories around. Production kept going long after the character had vanished from screens. In 2006, the Walt Disney Company bought the rights to Oswald back, making the rabbit again part of the Disney universe.

Mickey Mouse postcards, around 1931 (© Disney).

Mickey Mouse

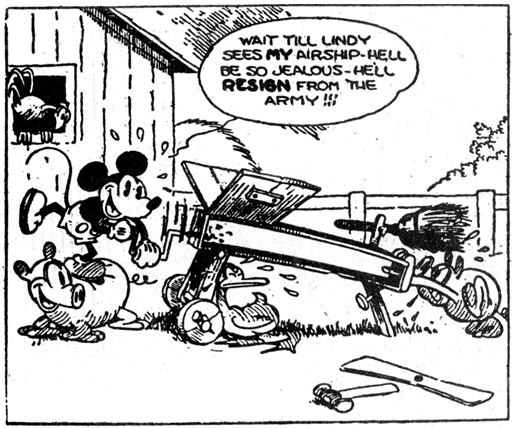

In 1927, Disney was devastated about losing his first cartoon star, Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, and almost his entire studio. For the third time he had lost everything he built up. But he and Ub Iwerks simply started all over again. Instead of a rabbit, they redesigned their character into a mouse, whose cute look was reminiscent of Clifton Meek's 'Johnny Mouse'. Their new character, Mickey Mouse, also received a girlfriend, Minnie Mouse. The first two 'Mickey Mouse' cartoons produced, the silent films 'Plane Crazy' (1928) and 'The Gallopin' Gaucho' (1928), failed to get picked up by a distributor after a test screening, and were not widely released. Disney decided that the third 'Mickey' cartoon, 'Steamboat Willie' (1928), should be a sound film, featuring a synchronized soundtrack. While the Fleischers ('My Old Kentucky Home', 1926) and Paul Terry ('Dinner Time', 1928) had created sound cartoons before, 'Steamboat Willie' was more sophisticated and complex in the use of sound. Composer Carl Stalling had invented a click track to pair sound effects and music better to the visuals, a technique still used in animation today and nicknamed "mickeymousing". 'Steamboat Willie' became an overnight sensation and launched Mickey's stardom. New cartoons were demanded and produced. Starting with 'The Karnival Kid' (1929), Mickey began speaking, with his voice provided by Disney himself. Peg-leg Pete, a character from Disney's 'Alice' films, was recast as Mickey Mouse's arch enemy. Originally, the big black cat had a peg-leg, but animators had trouble remembering whether it was his left or right one. Starting with 'Moving Day' (1936), he was drawn with two legs and renamed simply Pete. To expand the mouse's universe, Ub Iwerks also designed other characters, like Mickey's friends Horace Horsecollar (1928), Clarabella Cow (1929) and his dog Pluto (1930).

In the 1930s, Mickey Mouse became a global sensation. Film theaters programmed his cartoons to draw audiences. Some 'Mickey Mouse' cartoons have become classics, for instance 'The Mad Doctor' (1933), 'Thru the Mirror' (1936) and 'Brave Little Tailor' (1938). Products with Mickey's face on it sold in the millions. In 1935, the happy mouse received a special award from the League of Nations (a forerunner of the U.N.) for being a "universal goodwill ambassador". The character made Disney rich, respected and famous, but the best part was that in 1930, he could finally establish a stable independent company, the Walt Disney Studios.

'Lost on a Desert Island', the first Mickey Mouse newspaper strip in 1930, was largely based on 'Plane Crazy' (© Disney).

Mickey Mouse comics

On 13 January 1930, the first 'Mickey Mouse' newspaper comic was published. Walt wrote the initial scripts, while Ub Iwerks did the artwork. Already after a month, Iwerks left to start his own studio. For the comic strip, he was succeeded by Win Smith, who also quit unexpectedly. After that, Jack King, Hardie Gramatky and Roy Nelson spent short periods ghosting episodes, until Floyd Gottfredson stepped in as the main artist for several decades. Aided by writers Ted Osborne, Merrill De Maris and Bill Walsh, Gottfredson shaped 'Mickey Mouse' into a marvellous long-running comic series, distributed by King Features Syndicate. Disney was glad, because now he could safely leave the comic to others, while concentrating on his animation studio, which was already enough work on its own. In 1932, Mickey Mouse received his own magazine, Mickey Mouse Magazine (1932-1940), distributed monthly through dairy companies.

Silly Symphony movie posters for 'King Neptune' (1932) and 'The Old Mill' (1937) (© Disney).

Silly Symphonies

While Disney could have easily remained satisfied with Mickey Mouse's success, he launched a new animated series in 1929, called 'Silly Symphonies'. These were one-shot cartoons based on famous fairy tales, fables, nursery rhymes or novels. Overall, the 'Silly Symphonies' were mood pieces strongly driven by music and used as a testing ground for the studio's technical and graphic experiments. Several have become timeless classics, including 'The Skeleton Dance' (1929), 'Flowers and Trees' (1932), 'Santa's Workshop' (1932), 'The Three Little Pigs' (1933), 'Old King Cole' (1933), 'The Pied Piper' (1933), 'Lullaby Land' (1933), 'The Grasshopper and the Ants' (1934), 'The Tortoise and the Hare' (1935), 'The Cookie Carnival' (1935), 'Who Killed Cock Robin?' (1935), 'Music Land' (1935), 'The Country Cousin' (1936), 'Little Hiawatha' (1937), 'The Old Mill' (1937) and 'The Ugly Duckling' (1939).

However, audiences had to warm up to this series, since Mickey didn't star in them. A 'Silly Symphonies' Sunday newspaper page was launched in 1932, written and illustrated throughout the years by Earl Duvall, Ted Osborne, Al Taliaferro, Bob Grant, Hubie Karp, Paul Murry and more. Most were adaptations of the cartoons themselves, but new storylines were also created. The character 'Bucky Bug was loosely based on the insects in the short 'Bugs in Love' (1932), but he already appeared in the Sunday comic strips before the film was released. Several characters introduced in the 'Silly Symphonies' shorts moved on to much longer careers in their comic adventures, such as The Big Bad Wolf and the Three Little Pigs (1933), Little Hiawatha (1937) and, most famously, Donald Duck (1934).

Donald and Mickey in 'Orphan's Benefit', 1934 (© Disney).

Goofy and Donald Duck

The downside of Mickey Mouse's massive global popularity was that he grew into an incorruptible hero. Concerned parents expected him to remain a good role model for their children, which limited the happy mouse's creative possibilities and eventually his screen appearances as well. From the mid-1930s on, Mickey was upstaged by new cartoon characters. In the Mickey Mouse short 'Mickey's Revue' (1932), a dim-witted and clumsy dingo made his debut. Initially a mere side character called "Dippy Dawg", he was eventually redesigned by Art Babbitt and Frank Webb and renamed Goofy. His voice was provided by former circus clown Pinto Colvig. In the 'Silly Symphony' short 'The Wise Little Hen' (1934), Donald Duck made his first appearance. The duck was designed by Dick Huemer, Dick Lundy and Art Babbitt, while Clarence Nash gave him his iconic quacking voice. Goofy and Donald were given significant supporting roles in the Mickey Mouse cartoon 'Orphan's Benefit' (1934), where they provided much of the comic relief.

Starting with 'Mickey's Service Station' (1935), Donald and Goofy teamed up with Mickey on a regular basis. Several cartoons featuring the trio have become classics, including 'The Band Concert' (1935), 'Moving Day' (1936) and 'Clock Cleaners' (1937). But it was already clear that audiences liked the dim dingo and short-tempered duck more than Mickey. Donald received his own series beginning with 'Don Donald' (1937). He and Goofy also starred as a comedy duo from 'Polar Trappers' (1938) on, until Goofy received his own solo series, kicked off by the cartoon 'Goofy and Wilbur' (1939). While Mickey appeared in fewer and fewer theatrical shorts, Donald and Goofy effectively became Disney's new stars. In 1937, Mickey's dog Pluto also received a spin-off series. He had already proven his potential in the classic Mickey cartoons 'Playful Pluto' (1934) and 'Pluto's Judgment Day' (1935).

Donald Duck starred in more theatrical cartoons than any other Disney character. His girlfriend, Daisy Duck, was a co-star in several shorts, as were Donald's nephews Huey, Dewey and Louie, his cousin Gus Goose and his dog Bolivar. All originated in Donald's theatrical cartoons, but became far more famous in the comic stories. The only secondary characters from the 'Donald Duck' shorts to actually receive a notable spin-off theatrical cartoon series of their own (and a long-running comic series to boot) were the chipmunks Chip 'n' Dale.

Goofy saw his popularity increase after World War II, when he starred in a series of hilarious thematic shorts, in which he tried out a wide variety of hobbies and shorts. Nicknamed the 'How To...' series, Goofy's antics lead to disastrous results. Several of these cartoons have become classics, including 'Tiger Trouble' (1945), 'Hockey Homicide' (1945) and 'Goofy Gymnastics' (1949).

Promotional art for 'Clock Cleaners' (© Disney).

Disney comics

Over the course of the 1930s, Disney's characters found their way to other printed media besides the newspapers. Reprints of the 'Mickey Mouse' newspaper comic appeared in the several incarnations of Mickey Mouse Magazine (1932-1940), which was initially a digest-sized monthly distributed through dairy companies. In 1933, Disney struck a deal with Whitman, a subsidiary of Western Publishing, to rework newspaper strips for the 'Big Little Book' children's book series. In 1937, Western also began producing the Mickey Mouse Magazine in a partnership with publisher Kay Kamen. The magazine was transformed into actual comic book format in 1939 and then quickly evolved into 'Walt Disney's Comics & Stories' (October 1940), produced by Western Publishing and published by Dell Comics. It still featured reworked Sunday pages from the 'Mickey Mouse' and 'Silly Symphonies' strips, but eventually new material was produced directly for these comic books.

Mickey Mouse Magazine issues of November 1933 and December 1935. The early issues were promotional magazines for dairy companies (© Disney).

Donald Duck comics

Donald Duck's comic career also started in Bob Karp and Al Taliaferro's 'Silly Symphonies' comic in 1934. Floyd Gottfredson then used him as a side character in his 'Mickey' newspaper serials. In 1937, Ted Osborne and Taliaferro created a daily gag strip with Donald and his nephews, followed by a Sunday page a year later. It however took an oddly long time before the aggressive duck received his own adventure series. The first attempts happened abroad: in Britain by cartoonist William A. Ward. and in Italy by Federico Pedrocchi. In 1942, Carl Barks and Jack Hannah gave Donald his first U.S. adventure comic in the 'Four Color' series by Dell Comics. Barks continued to write and draw adventures with Donald Duck throughout the following decades, fleshing out the duck's character, giving him a hometown (Duckburg) and a wide range of friends, relatives and enemies. Especially Donald's rich uncle Scrooge McDuck became so popular that he received his own solo comic book in 1953. In 1952, both Donald and Mickey were given their own comic book titles by Dell Comics.

Goofy comics

In contrast, Goofy's comics career pales compared with Mickey and Donald's. He was usually given the role as Mickey's sidekick in comic stories and only starred in a couple of gag stories and humorous short stories on his own. In 1949, Goofy received his own sidekick, Ellsworth the mynah bird, created by Bill Walsh and Manuel Gonzales. In 1965, Del Connell and Paul Murry reimagined Goofy as a superhero named 'Super Goof'. This led to a popular series of spin-off comics. Another notable alternate comic version of Goofy was made by Adolfo Urtiága and the Jaime Diaz Studio, who, between 1976 and 1987, made several full-length humorous 'Goofy' comic books, in which the dingo appears as famous historical figures or characters from literary classics.

'Donald Duck Finds Pirate Gold' (1942), Carl Barks' first Donald Duck story (© Disney).

Other character-driven Disney comics

New stories with other Disney characters continued to appear in 'Walt Disney's Comics & Stories'. Amazingly enough, several only appeared in one single theatrical cartoon, such as Bucky Bug, Gus Goose, Little Hiawatha and Witch Hazel. Others were side characters in feature films, such as Panchito, Jose Carioca, Br'er Rabbit, Gus and Jaq, Thumper, Tinkerbell, Madam Mim and the little dog Scamp, was only seen during the final five minutes of 'Lady and the Tramp' (1955). But all these minor theatrical Disney characters are still recognizable to many people because they enjoyed a much longer career as stars in the comics. Likewise, some recurring cast members in the Mickey, Donald and Goofy comics - Chief O' Hara, The Phantom Blot, Gladstone Gander, Grandma Duck, Fethry Duck and Ellsworth the Mynah Bird, to name but a few - have never even appeared on the big screen. Thanks to Disney's huge back catalog, many crossovers between characters from different films and series have occurred in the comics.

Seventh issue of Walt Disney's Comics and Stories, and Four Color Comics one-shot #92, starring Pinocchio (© Disney).

Disney comics abroad

As early as the 1930s, unlicensed 'Mickey' and 'Donald' comics appeared in Japan, the United Kingdom, Italy and Yugoslavia. To thwart them, official local Disney magazines were launched. During World War II, many countries occupied by the Axis Powers banned Disney comics, like all other U.S. media. Having lost the foreign market in Europe and Southeast Asia, Disney invested in Latin American media instead. From the early 1940s on, Disney comics became more widespread in this continent, with a focus on characters like Jose Carioca. After the Liberation of Europe in 1944-1945, new licensed Disney magazines were launched in Continental Europe. In some countries, like Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland, The Netherlands, Germany and Spain, they reached immense popularity. While Disney comics lost their bestseller status in the United States by the 1960s, quite the opposite was true in Europe and Latin America. Starting in 1962, the Walt Disney Studios produced exclusive stories for publications abroad. Several foreign publishers received an official license to produce their own stories, such as Édi-Monde/Hachette in France, Mondadori in Italy, Abril in Brazil, De Geïllustreerde Pers in The Netherlands and Gutenberghus in Denmark, which were then syndicated all over the world. Over the decades, foreign licensing led to new characters, series and spin-offs. As of today, Egmont (Scandinavia), DPG (The Netherlands) and Disney's own publishing division in Italy are the largest producers of Disney comics worldwide.

Dutch and Italian Disney magazines celebrating Mickey's 90th birthday in 2018 (© Disney).

Disney studio

Walt Disney himself had almost nothing to do with his comics production, other than they all appeared under his name. For a long time, artists and writers weren't credited for their work, although this was often the policy of the publishers and distributors. It took until the 1960s before the identities of these comic authors became publicly known, most notably of the "Good Duck Artist" Carl Barks. Although Disney's animators also remained unknown to the general public, they at least received credit on-screen. Nine of his most prominent animators and directors went down in history as the "Nine Old Men": Les Clark, Marc Davis, Ollie Johnston, Milt Kahl, Ward Kimball, Eric Larson, John Lounsbery, Wolfgang Reitherman and Frank Thomas. Some animators have become legendary in their own right, such as Ub Iwerks, Fred Moore, Art Babbitt, Bill Tytla, Hamilton Luske and Norm Ferguson.

Among the artists who once worked in Disney's animation department (and later often drew comics with his characters too) were Fred Abranz, Pete Alvarado, Mike Arens, George Baker, Carl Barks, Jack Bogle, Jack Bradbury, Don Bluth, Stephen Bosustow, Carl Buettner, Don R. Christensen, Walter Clinton, Ron Cobb, George Crenshaw, Shamus Culhane, Bob Dalton, Jim Davis, Owen Fitzgerald, Chuck Fuson, Mo Gollub, Chad Grothkopf, Frank Grundeen, Don Gunn, Joseph H. Hale, Jack Hannah, Pete Hansen, Jerry Hathcock, Gene Hazelton, Ralph Heimdahl, Harry Holt, Cal Howard, Al Hubbard, Earl Hurd, Ken Hultgren, A.C. Hutchison, Chris Ishii, Willie Ito, Gus Jekel, Chuck Jones, Volus Jones, Lynn Karp, Selby Kelly, Walt Kelly, Hank Ketcham, Jack King, Jack Kirby, Tack Knight, Bob Kuwahara, Ken Landau, Rudy Larriva, Harold Mack, Tom Massey, Bob McKimson, Chuck McKimson, Tom McKimson, Frank McSavage, Bill Melendez, Vernon Miller, Bob Moore, Paul Murry, Milt Neil, Dan Noonan, Tom Okamoto, Virgil Partch, Ray Patin, Ray Patterson, Perce Pearce, Fred Peters, Enrique Riverón, Cliff Roberts, M.T. "Penny" Ross, Dr. Seuss, Dick Shaw, Larry Silverman, Paul J. Smith, Fred Spencer, Tony Strobl, Cecil Surry, Iwao Takamoto, Frank Tashlin, Riley Thomson, Charles Thorson, Reuben Timmins, Don Tobin, Gil Turner, Cliff Voorhees, Stan Walsh, Bill Weaver, Ralph A. Wolfe, Bill Wright and Kay Wright. To this day, Disney remains the only name general audiences know, but since 1987, the company has given these unsung contributors more credit through the bi-annual Disney Legend Awards.

Carl Stalling in 1930 at the piano with standing around him Johnny Cannon, Walt Disney, Burt Gillett, Ub Iwerks, Wilfred Jackson and Les Clark. Seated are animators Jack King and Ben Sharpsteen.

Disney's technical vision

While his artists did most of the production work, Walt Disney guarded the overall quality. He unified the talents of thousands of people into one uniform product. Millions of dollars were invested to improve the look and quality of his cartoons. He strove hard to make his characters and fantasy worlds believable. As he acquired more skilled artists, the animation became smoother and more fluid. When his paper-and-ink creations moved, there was weight and gravity to their motions. They even seemed to have a mind of their own. 'The Three Little Pigs' (1933) was a milestone in this field since it featured three identical looking characters who were still distinct by the way they acted on screen, as Chuck Jones once observed. Another milestone was 'Playful Pluto' (1934), in which Pluto gets stuck on a piece of flypaper and really appears to be thinking how to get rid of it. Disney went so far as to write out character descriptions so that his staff could understand Mickey, Donald and Goofy's personalities and animate them accordingly. Voice actors were instructed to never go public as "the voice of...", to keep the illusion alive. Although Disney sometimes used celebrity voice actors (Basil Rathbone, Sterling Holloway, Peggy Lee, Phil Harris) he picked them out in function of the role, rather than for name recognition.

Disney wanted his cartoons to have the same feel of a live-action film. To achieve this, cinematic techniques were imitated, the most famous example being the multi-plane camera in 'The Old Mill' (1937) which can zoom into backgrounds. Lotte Reiniger and Ub Iwerks had pioneered a similar technique before, but the Disney Studios perfected it. Through an exclusive contract with Technicolor, Disney also improved on earlier color cartoons like J.R. Bray's 'The Debut of Thomas Cat' (1920) and Ub Iwerks' 'Fiddlesticks' (1930) by making the first truly full-color animated cartoon, 'Flowers and Trees' (1932). Disney's was the only studio to have a separate department for mood and atmospheric effects. As the artwork became richer, backgrounds showed incredible attention to detail. The look of classic European paintings and book illustrations was mimicked. No costs were spared to overcome huge technical difficulties. Dazzling perspectives, intricate machinery, light and shadow effects, flames, wind, streaming water and dozens of characters appearing all in the same scene... Disney pulled it all off. In some cases his cartoons even did things live-action couldn't imitate at the time.

Disney's musical vision

To add prestige, Disney used famous classical scores on his soundtracks. Many have become animation clichés, such as Gioacchino Rossini's 'William Tell Overture', whenever characters are running, or Franz Liszt's '2nd Hungarian Rhapsody', whenever pianos are played. But he also had composers write original music for him, such as Carl Stalling (who later joined Warner Brothers), Frank Churchill (who wrote 'Who's Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?' and the songs for 'Snow White', 'Pinocchio', 'Dumbo' and 'Bambi') and the Sherman Brothers (who wrote most of the soundtracks of 'Mary Poppins' and 'Jungle Book'). Several Disney songs have become popular standards. Famous conductors like Arturo Toscanini and Jerome Kern praised his use of music.

Walt Disney in front of the Pinocchio storyboard.

Disney's narrative vision

On a technical level, Disney was rarely matched by any of his competitors. The narratives of Disney's cartoons display a real gift for storytelling. He knew how to keep a scene solid, understandable and entertaining. One animator, Webb Smith, invented the storyboard to plot out and time scenes better. These were illustrated scripts in sketch form, inspired by comic strip lay-outs. The method was quickly picked up by other studios, even in live-action, and is nowadays a global standard practice for all film and TV productions. Disney was rich enough to afford test screenings in pencil form, while rival cartoon studios had to plan out everything more in advance, only seeing the end result in complete action when their short was finished. Disney had the luxury that he could still make changes afterwards if he noticed a continuity error or felt a scene fell flat. He instinctively knew how his viewers would respond to the story, and was very aware of the difference between what was funny in the studio and how it would come across on screen. For the same reason, he dismissed any attempt to be trendy, preferring to keep his work as timeless as possible.

The Disney magic

Disney's high quality technical and narrative standards explain why his productions remain eternal audience favorites. Children love his films, parents feel comforted by them and many other adults just enjoy their nostalgia. Disney is an inviting world to revisit time and time again. During the 1930s and 1940s, when the Great Depression and World War II were in full effect, millions of viewers found escapism in Disney's cartoons and comics. The same happened after the war, whenever people were in need of a little relief. Today, the company still markets itself as a dream factory, famous for their fun, heartwarming and tender moments.

Nightmarish forest sequence from 'Snow White & the Seven Dwarfs' (© Disney).

The Disney nightmare sequences

Despite Disney's reputation for clean family entertainment, certain cartoons, particularly the animated features, feature quite intense, nightmarish imagery. Some parents expressed worry about scenes in 'The Mad Doctor', 'Pluto's Judgement Day', the Witch and haunted forest in 'Snow White', Stromboli, the Coachman, the donkey transformations and Monstro in 'Pinocchio', the Rite of Spring and Night on Bald Mountain in 'Fantasia', the 'Pink Elephants' hallucination in 'Dumbo', Bambi's mother getting shot, The Headless Horseman in 'The Adventures of Ichabod', Donald freaking out from starvation in 'Mickey and the Beanstalk' and Aurora being led away by a spell to prick herself on the spinning wheel in 'Sleeping Beauty'. Yet all Disney pictures have a happy end, which probably helps the traumas ebb away.

Disney's influence on cartooning

Right from the start, Disney made many public appearances, presenting himself as loveable "Uncle Walt", a friend of all children. He became as famous and recognizable as any Hollywood celebrity, the only animator to rise to that status. Film critics respected him as an innovative cineast. The success of his cartoons launched the Golden Age of Animation (1930-1960), when many film studios started their own animation departments to compete with Disney. Particularly during the 1930s, nearly every cartoon studio seemed to have a happy, cheerful Mickeyesque character in fairy tale stories with sing-a-long songs. Warner Brothers' 'Merry Melodies' and 'Looney Tunes' were directly inspired by 'Silly Symphonies'. Even the fact that many cartoon characters have four fingers on each hand and wear gloves was derived from Mickey, who was redesigned with gloves to make his black hands more visible on the screen, and who lost a finger to save money on animation.

Aspects of Disney characters and personalities have inspired the works of subsequent animators and comic artists. The mice in Disney's 'The Country Cousin' (1936) led to Chuck Jones' 'Sniffles' and Hanna- Barbera's 'Jerry'. Without Donald Duck, Tex Avery's 'Daffy Duck', Al Fagaly's 'Super Duck', Steve Gerber & Val Mayerik's 'Howard the Duck' and Charlie Christensen 'Arne Anka' wouldn't exist. Max Hare was the prototype for Bugs Bunny, while Pablo the Penguin strongly influenced Walter Lantz's Chilly Willy. Lantz' Fatso the Bear and Hanna-Barbera's Yogi Bear borrowed the mustard from Disney's 'Humphrey Bear' cartoons. In Britain, Leo Baxendale's 'Little Plum' was modeled after Hiawatha, while Pepo's 'Condorito' in Chile was created as a reaction to Joe Carioca. The Belgian artist Jef Nys used the look of the Evil Queen from 'Snow White' for the Queen of Onderland in 'Jommeke' and the gnomes Schommelbuik and Knaagtand in his other comic 'Langteen en Schommelbuik' are respectively modelled after the dwarves Happy and Dopey from the same film. Rune Andréasson's 'Pellefant' was inspired by Dumbo, while Juanjo Guarnido couldn't help but think of Bagheera in 'Jungle Book' when he designed the title character of the 'Blacksad' comic series. In some cases, animators deliberately tried to avoid mimicking Disney. Zdeněk Miler created 'Krtek' ('The Little Mole'), because he thought Disney had never used a mole in one of his films. Only later did he find out the existence of Mr. Mole in 'The Adventures of Mr. Toad' (1949).

The speed effects in Disney's 'The Tortoise and the Hare' (1935) were also widely copied and eventually surpassed by Tex Avery. The idea of bringing characters in storybooks to life was pioneered by Disney's 'Mother Goose Melodies' (1931). 'Mickey Gala's Premier' (1931) featured Mickey meeting various caricatures of famous Hollywood stars, an idea that had been done before in Pat Sullivan and Otto Messmer's 'Felix the Cat' cartoon 'Felix in Hollywood' (1923), but became more prominent after Disney did it. Disney's 'Snow White' (1937) set the standard for every feature-length animated film. And 'Fantasia' (1940) became the template for every animated feature with solely classical music on its soundtrack, such as Bob Clampett's 'A Corny Concerto' (1942), Art Clokey's 'Gumbasia' (1955), Chuck Jones' 'What's Opera Doc?' (1957) and Bruno Bozzetto's 'Allegro Non Troppo' (1976).

Film poster for 'Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs' (© Disney).

Snow White

In 1937, Disney made the first animated feature film: 'Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs'. While there had been predecessors, like Quirino Cristiani's lost film 'El Apóstol' (1917), Lotte Reiniger's 'Die Abenteuer des Prinzen Achmed' (1926), Aleksander Ptushko & A. Vanichkin's 'Novyy Gullivyer' (1935), Ladislaw Starewicz's 'Le Roman de Renard' (1937) and Ferdinand Diehl's 'Die Sieben Raben' (1937), 'Snow White' dwarfed them all. The film showed just how much progress the studio had made in only a decade's time. The fairy tale adaptation is an extraordinary cinematic experience. The picture has atmosphere, makes viewers laugh, cry, feel frightened and keeps them as entertained as any live-action picture. To balance out the main narrative, Disney also included several musical sequences, which became another hallmark of his animated features. 'Snow White' won critical praise, eight Oscars and was a worldwide blockbuster. The instant classic attracted celebrity fans like painter Piet Mondriaan, scientists Kurt Gödel and Alan Turing, film director Sergei Eisenstein, the British Royal Family, president Franklin D. Roosevelt and, notoriously, Benito Mussolini, Adolf Hitler and Joseph Goebbels.

A few days before the film's release, an official newspaper comic strip adaptation ran in the papers, scripted by Merrill de Maris and drawn by Hank Porter. It would later be made available in comic book format too. Since 'Snow White' was such a box office hit, new animated features were created every few years, combined with promotional comics. For decades, Disney brought back all their classic movies in theatrical rotation every now and then, so younger generations could discover them too. The old promotional comics were then reprinted as well.

Film posters for 'Pinocchio' and 'Bambi' (© Disney).

World War II

While Disney is the name behind an iconic multinational, it is often forgotten that he frequently took huge commercial risks. He constantly came up with new projects and disliked making sequels. Some of his animated shorts or features received mixed or even bad reviews and would only become classics several years, even decades, later. Two of those were his 1940 animated features, 'Pinocchio' and 'Fantasia'. Both surpassed the technical and narrative achievements of 'Snow White' and are often regarded as his personal masterpieces. 'Pinocchio' is an emotionally powerful film, rich in detail and featuring some of the most dazzling animated sequences ever created by hand. 'Fantasia' is arguably Disney's most controversial and experimental work. An anthology film where every segment is set to a famous classical composition. Yet at the time of their release, both ambitious films received polarizing reviews because of their darker content. 'Fantasia' in particular was deemed too kitschy in the eyes of high-brow classical music fans, while general viewers felt it was too pretentious.

Disney was devastated and felt he had reached too high. It convinced him that he better gave audiences what they wanted from now on: unpretentious family entertainment. All movies he made after 1940 were still quality pictures, but lacked the innovative spirit from before. Instead, viewers now favored the far wilder and funnier cartoons at Warner Brothers (Looney Tunes), MGM ('Tom & Jerry', 'Droopy') and Walter Lantz ('Woody Woodpecker'). Disney not only lost his interest in animation, but also many of his employees as the result of a long strike in 1941.

Wartime propaganda films (© Disney).

The early 1940s were overall a depressing time for Walt, whose beloved mother passed away in 1940. His grief was reflected in 'Pinocchio' (1940), 'Dumbo' (1941) and 'Bambi' (1942), which all feature child protagonists losing a parent and going through tough emotional ordeals. Yet while 'Dumbo' was an unexpected hit, 'Bambi' didn't do well at the box office at the time. To keep his studio profitable, Disney appealed to another foreign market in Latin America. In his feature films, 'Saludos Amigos' (1942) and 'The Three Caballeros' (1943), Donald Duck visits South America, meeting new characters like the Brazilian parrot Jose Carioca and the Mexican rooster Panchito Pistoles.

Another reason why 'Pinocchio' and 'Fantasia' didn't do well commercially is that Hollywood pictures were banned in all Axis-occupied countries during World War II. However, the war also gave Disney new sources of income when the United States got involved in the conflict on 7 December 1941. The U.S. government commissioned the studio to produce various propaganda cartoons. Some, like 'Stop That Tank' (1942), 'The Grain That Built a Hemisphere' (1943) and 'Victory Through Air Power' (1943) were instruction films, strictly intended for military audiences. Disney also educated the masses by reminding them of the importance of buying war bonds ('Donald's Decision', 1942), saving precious material ('Out Of The Frying Pan, Into the Firing Line', 1942) and paying income taxes ('The New Spirit', [1942], and 'The Spirit of '43', [1943]). Some cartoons criticized Nazism, such as 'Der Fuehrer's Face' (1942), 'Education for Death' (1943) and 'Reason and Emotion' (1943), while more straightforward entertaining shorts were 'Donald Gets Drafted' (1942), 'The Vanishing Private' (1942), 'Sky Trooper' (1942), 'Fall Out, Fall In' (1943), 'The Old Army Game' (1943) and 'Home Defense' (1943), in which Donald is bullied around in the army by Pete. In 'Commando Duck' (1944), Donald is actually sent to the South East Asian jungle, where he fights the Japanese. While these war-time propaganda cartoons put most of the studio's other productions on hold for two years, they did help the company out of the red.

Interestingly enough, the Axis Forces also made propaganda cartoons and in some of these, Mickey and Donald are ridiculed as "enemies". The Japanese cartoon 'Omochabako' (1936) by Komatusuzawa Hajime, for instance, features the folk hero Momotaro battling a giant Mickeyesque mouse flying on a bat. Raymond Jeannin's 'Nimbus Libéré' (1944) was made in Vichy France and stars, apart from André Daix' 'Professeur Nimbus', Mickey, Donald and even Popeye bombing France. The most peculiar non-official appearance of Mickey was 'Mickey à Gurs' (1940), a text comic created by Horst Rosenthal while imprisoned in a Nazi POW camp.

Post-war career and activities

After World War II, U.S. troops liberated many countries from the Axis, which helped Disney regain his pre-war markets. Yet since there was still not enough money to make proper feature films, four anthology features were made instead: 'Make Mine Music' (1946), 'Fun and Fancy Free' (1947), 'Melody Time' (1948) and 'The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad' (1949). Like most features Disney made between 1942 and 1950, these are rarely shown in their original form today. The individual segments are often repackaged in new compilation videos. In 1950, Disney's first full-blown animated feature film in eight years, 'Cinderella', was a box office hit. However, his next picture, 'Alice in Wonderland' (1951), based on the Lewis Carroll novel, received bad reviews. 'Alice' had been a passion project of Disney for years and the fact that it failed frustrated him deeply. 'Peter Pan' (1953) and 'Lady and the Tramp' (1955) were on the other hand much better received by audiences.

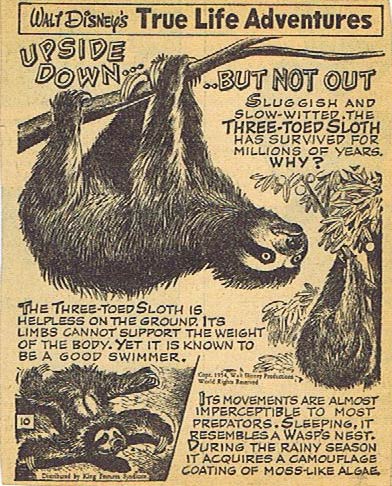

'True Life Adventures' newspaper feature, drawn by George Wheeler (1955).

Live-action films and nature documentaries

After the war, Disney became preoccupied with other projects, such as live-action films. 'Song of the South' (1946), 'Treasure Island' (1950), '20.000 Leagues Under the Sea' (1954), 'Old Yeller' (1957) and 'Mary Poppins' (1964) became beloved family classics. Other Oscar winners were his 'True-Life Adventures' nature documentary films. They showed live-action footage of real animals in the wild. But Disney wouldn't be Disney if he didn't occasionally make these scenes a little more entertaining by playing with the editing and adding funny background music. Once again, animals were anthropomorphized under his watch, even if they weren't cartoon characters. Oddly enough, even 'True-Life Adventures' was adapted into a comic strip, an educational newspaper feature written by Dick Huemer and drawn by George Wheeler, running from 1955 until 1973.

Television series

Walt Disney was also one of the few Hollywood producers who saw the potential of television. His studio had a library worth of old cartoons which could be rebroadcast on the small screen. He created two long-running children's TV shows, 'The Mickey Mouse Club' (1955-1996) and 'Walt Disney's Wonderful World Of Color' (1961-1969), which showed these shorts to new generations of children. The programs were also excellent tools to promote every upcoming Disney film, often hosted by "Uncle Walt" himself. Disney also produced popular live-action TV series, such as 'Davy Crockett' (1954-1955) and 'Zorro' (1957-1959). 'Davy Crockett' was adapted in a newspaper comic by Ed Herron, Jim McArdle, Jack Kirby and Jim Christiansen, although not endorsed by Disney. He couldn't sue them either, since Crockett was a historical character, so in response Disney simply came up with his own comic book series, published by Dell. The artists behind these comic book stories were John Ushler, Nick Firfires and Jesse Marsh, among other people. Disney's official 'Zorro' newspaper comic strip was drawn by Alex Toth, while in the Netherlands Hans G. Kresse made a comic strip version of this particular TV series for the magazine Pep.

Walt Disney presenting the map of Disneyland.

Disneyland

On 17 July 1955, Disney's most ambitious project opened its doors - a theme park called Disneyland. Theme parks had existed before, but Disneyland was something altogether unprecedented. The park was built with recreations of various locations depicted in his cartoons. Actors walked around in costumes depicting the familiar Disney characters. In his park, Disney made his fictional worlds as real as possible. Children could now actually meet Mickey, Donald and friends. "The happiest place on Earth" is one of the most visited locations on the planet. Even Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev was outraged during his 1959 U.S. visit when he wasn't allowed to go to Disneyland because his safety couldn't be guaranteed. The success of Disneyland led to new parks being built all around the globe: Disney World in Orlando, Florida (1971), Tokyo Disneyland in Japan (1983), Euro Disney in Paris, France (1992), Hong Kong Disneyland Resort (2005) and Shanghai Disneyland Park in China (2016).

Final years and death

Disney's next feature, 'Sleeping Beauty' (1959), marked a change in Disney's trademark graphic style. Influenced by Ronald Searle, the drawings became more angular and sketchy, and this style remained until halfway through the 1980s. Audiences didn't react well to this at the time, but 'Sleeping Beauty' did become more appreciated in later years. '101 Dalmatians' (1961) was another box office hit, but 'The Sword in the Stone' (1963) was Disney's least popular feature to date. In 1966, A.A. Milne's 'Winnie the Pooh' stories were adapted into a cartoon series, with respect for the original illustrations by E.H. Shepard. It evolved into one of the studio's most popular franchises, still generating new installments decades later. Unfortunately, Walt Disney passed away from lung cancer the same year. His death made universal headlines. Contrary to urban legend, he was not cryogenically frozen, but cremated. The final picture with his involvement was the swinging 'Jungle Book' (1967), which was halfway through production at the time of his death, and then finished posthumously by his staff, becoming a box office success.

Movie posters for 'Sleeping Beauty' and 'One Hundred and One Dalmatians' (© Disney).

Walt Disney Productions after its founder's death

After Walt Disney's death, his studio continued with their ongoing line of entertainment products, operating as Walt Disney Productions until it was rebranded into The Walt Disney Company in 1986. Between 1957 and 1972, many animation film studios had closed down or switched to creating low-budget kids TV series. Even though the Walt Disney Company is the only one to survive to this day, Disney's passing is still seen as the symbolic end of the Golden Age of Animation. Businesswise, the company stayed on top. New theatrical shorts appeared more rarely, but their feature films, both old and new, still brought in crowds. Every new Disney cinematic release remained the event of the year for children. Their TV shows and classic theatrical cartoons kept re-running, and the theme parks were still lucrative. From 1984 on, the company carefully made all their classic cartoons available on video, one by one. Soon Walt Disney Home Video became a babysitter in many households. Around the same time, the company started producing animated TV series, creating successes like 'Gummi Bears' (1985-1991), 'DuckTales' (1987-1990), 'Chip 'n' Dale Rescue Rangers' (1989-1990), 'Darkwing Duck' (1991-1992), 'Goof Troop' (1992-1993), 'Gargoyles' (1994-1997) and 'Quack Pack' (1996), following it up during the 2000s and 2010s with 'Disney's House of Mouse' (2001-2003) and various live-action series aimed at prepubescent girls. Equally popular since 1981 are the 'Disney on Ice' traveling tours of ice skating shows.

But critically, many of the post-1966 Disney releases met with lackluster reception and failed to reach the iconic status of their superior work from before. It took until Robert Zemeckis and Richard Williams' 'Who Framed Roger Rabbit?' (1988), a live-action film that paid homage to the Golden Age of Animation, before Disney experienced a renaissance. The film featured many cameos of famous cartoon characters, naturally from the Disney Studios too. Their classic cartoons were rediscovered by the general public and a whole string of new animated features became critical and commercial successes: 'The Little Mermaid' (1989), 'Beauty and the Beast' (1991), 'Aladdin' (1992) and 'The Lion King' (1994) won several Oscars in the process. 'Beauty and the Beast' was the first animated feature to be nominated for "Best Picture". By initially taking care of the licensing, distribution and merchandising of the films by the Pixar studios, The Disney Company also got involved with CGI animation. After Disney bought the company in 2006, they released successful CGI pictures with 'Wall-E' (2008), 'Up' (2009), 'Inside Out' (2015) and 'Luca' (2021), among others. 'Wall-E' and 'Up' were once again nominated for "Best Picture" during the Oscars, but had to be satisfied with winning "Best Animated Picture" instead. 'Frozen' (2013), a CGI feature produced by the Disney studio, not only won the Oscar for "Best Animated Picture", but also became the most commercially successful animated feature film of all time.

The famous 'Mickey Mouse' logo, used as intro to his theatrical cartoons.

Controversy

Although Disney has been the market leader in animation since 1928, there is a misconception that his company created every single animated cartoon in existence. Their brand awareness is so huge that smaller cartoon studios hardly have a chance to make a name for themselves. Even if they have a hit, many viewers still think Disney made it. Their creativity is additionally obstructed by the fact that audiences expect all animation to be cute, innocent and family friendly. This is not only problematic for animators trying to do something different, but even for the Disney company itself. Deviating from their own formulas is considered a huge commercial risk. As a result many of their designs, characters and narratives are constantly recycled. Some are irritated by the corny and kitschy Disney clichés: happy sing-a-long songs, sweet princesses, funny animal sidekicks, songbirds helping in the household and lots of cute babies, bunnies and puppies.

Bibliophiles despise Disney for hijacking iconic fairy tales, legends and novels. Many of these stories were drastically simplified, sanitized and bowdlerized. Controversial scenes were removed and totally new plotlines, cute characters and obligatory happy ends added. In some cases, the original tales are nearly unrecognizable. Even worse is that these butchered versions have replaced the originals in the mind of the general public. To this day, audiences complain that adaptations of these stories are "not the same as in the Disney version", which has often forced modern-day creators to add the Disney additions to the stories, because people are so used to them. Sociologists feel the theme parks are the most disturbing aspect of these methods. Happy, safe and bland dream worlds outside the harsh reality of everyday life. Already the parks are the equivalent of an independent mini-state, with their own monetary units and park owners not allowing outside interference.

Some people feel spooked out about the Disney corporation's acquisitions of other companies. In later years, they bought ABC (1996), Jim Henson's Muppets (2004), Pixar (2006), Marvel (2009), LucasFilm (2012) and FOX (2018), Disney has its own TV channel (1983) and the streaming service Disney+ (2019), as well as a separate film company specializing in films for mature audiences, Touchstone Pictures (1984), which also has a TV department (1985). Disney's legal department is so powerful that they have sued various companies and individuals for copyright infringement, while trademarking characters they didn't even create, such as Snow White, Tinkerbell and Winnie the Pooh. Some Disney films, like 'The Lion King' (1994) which shares strong similarities with Osamu Tezuka's 'Kimba the White Lion' (1966), have been accused of plagiarism. Another matter is Mickey Mouse, who only partially entered public domain in 2024, almost 95 years after his debut cartoon. Other fictional characters created around the same time entered public domain decades earlier, but the Disney Company managed to legally postpone Mickey's expiration date far longer than common. Even today, only the earliest design of Mickey Mouse is now public domain, while the redesigned character itself remains trademarked. All this power has led to frequent accusations of global Americanisation, or better said, "Disneyfication".

Apart from his company, Walt Disney himself has also been subject of controversy. He was by all accounts a conservative man. Although he was interested in fine art and read classics of world literature, his personal taste tended to schmaltzy romanticism, cute characters and corny gags. The amazing technical achievements of his movies are often overshadowed by these elements. Animator Ward Kimball recalled that Disney was very fond of jokes where characters get poked in their behind. In almost all Disney cartoons there is at least one such scene. Disney often attributed his marketing talent to the fact that he was a common, average American and not only made his movies for children, but also mothers watching along in approval. Nevertheless, several of his employees remember him as a difficult taskmaster who rarely complimented them for all the work they did in his name. Disney could be very cold and spiteful towards people who disagreed with his policies. In the late 1940s, he testified before the House of Anti-American Activities and accused several former employees who left him after the 1941 strike of being "Communist sympathizers" and many were blacklisted from work for years. In later decades, Disney's reputation has been further tarnished with persistent but inconclusive rumors that he was sexist, racist, even anti-Semitic. Though most are present-day interpretations of questionable scenes in his work that were simply products of their time. All the other "evidence" are anecdotes that are difficult to verify, let alone date. A more critical biography of Walt Disney's life was released in 1994 by Marc Elliot under the title 'Walt Disney: Hollywood's Dark Prince'. It presented a darker picture of the famous entertainer than his popular perception. Over the years, many of the book's claims have been refuted by other authors.

Parody from Mad #19, 1955: 'Mickey Rodent' by Will Elder and Harvey Kurtzman.

Parody and satire

Since Disney is known for its clean innocent children's entertainment, the company has always been an easy target for subversive parodies, anti-capitalist and/or anti-American satire. This happened as early as the 1930s with the infamous Tijuana Bibles, where various comic characters were illegally depicted in pornographic activities. Among the more memorable later attacks have been Harvey Kurtzman and Will Elder's 'Mickey Rodent' (Mad Magazine, issue #19, 1955), Ed "Big Daddy" Roth's 'Rat Fink', Wallace Wood's infamous 'Disneyland Memorial Orgy' (1967), Robert Armstrong's 'Mickey Rat' and Eric Knisley's 'Mickey Death'. Marv Newland's 'Bambi Meets Godzilla' (1969) and Whitney Lee Savage's 'Mickey Mouse in Vietnam' (1969) were two infamous underground animated cartoons killing off beloved Disney characters. In Gerald Scarfe's animated short 'A Long Drawn Out Trip' (1971) Mickey lights a joint in one memorable scene, and in an animated intermezzo by Cal Schenkel in Frank Zappa's film '200 Motels' (1971) Donald Duck makes an odd appearance. The underground comic book 'Air Pirates Funnies' (1971) by Dan O'Neill, Bobby London, Shary Flenniken, Gary Hallgren and Ted Richards depicted Mickey and other Disney characters as sex and drug addicts. It was their determined and ultimately successful intention to be sued by Disney. Some scenes in Ralph Bakshi's 'Fritz the Cat' (1972) are direct satire of Disney characters, scenes and its family friendly reputation.

Pornographic cartoon parodies of 'Snow White' were made by David Grant ('Snow White and the Seven Perverts', 1973) and Picha ('Blanche-Neige, La Suite', 2007). In Woody Allen's 'Annie Hall' (1977) an animated segment by Chris Ishii parodies the Evil Queen from 'Snow White'. Ralph Bakshi's 'Coonskin' (1975) was created as a modern day political rendition of 'Song of the South'. Swedish cartoonist Charlie Christensen created 'Arne Anka' (1983-1995) as a vulgar version of Donald Duck until he was threatened by Disney to redesign his character. Dutch painter Peter Klashorst painted several canvases depicting Mickey, Goofy, Donald Duck and Uncle Scrooge, sometimes in family friendly images, but also a lot of pornographic spoofs. Disney parodies have been a staple of Matt Groening's 'The Simpsons', Trey Parker and Matt Stone's 'South Park', Andrew Adamson and Vicky Jenson's 'Shrek', Seth Green's 'Robot Chicken' and Seth MacFarlane's 'Family Guy'. In 2015, graffiti artist Banksy redesigned an abandoned theme park into the satirical 'Dismaland'. It was only open for a month before Banksy closed it down again.

Recognition

In 1932, Walt Disney was the first animator to receive an Academy Award, more specifically the Honorary Award, which he received for "the creation of Mickey Mouse". He won eight honorary Oscars for 'Snow White' (1937) and one for Fantasia (1940). In 1947, James Baskett became the first male African-American actor to win an (honorary) Oscar for his role in the Disney film 'Song of the South'. Disney won the very first Academy Award for Best Animated Short with 'Flowers and Trees' (1932). He received the same little statue for 'Three Little Pigs' (1933), 'The Tortoise and the Hare' (1934), 'Three Orphan Kittens' (1935), 'The Country Cousin' (1936), 'The Old Mill' (1937), 'Ferdinand the Bull' (1938) 'The Ugly Duckling' (1939), 'Lend a Paw' (1941), 'Der Fuehrer's Face' (1942) and 'Toot, Whistle, Plunk and Bloom' (1953). Posthumously, the studio also won the Oscar for Best Animated Short for 'Winnie the Pooh and the Blustery Day' (1968) and Ward Kimball's 'It's Tough to Be a Bird' (1969). In 1942, Disney was also the first animator to be honored with the Irving G. Thalberg Academy Award for his entire career.

With 15 awards and 49 nominations, Disney is hands down the most awarded animator in Oscar history. In fact, he entered the Guinness Book of Records for being the filmmaker who won the most Oscars, period! 'When You Wish Upon a Star' (1940), 'Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah' (1947), 'Chim Chim Cher-ee' (1964), 'Under the Sea' (1989), 'Beauty and the Beast' (1991), 'A Whole New World' (1992), 'Can You Feel the Love Tonight' (1994), 'Colors of the Wind' (1995), 'You'll Be in My Heart' (1999), 'If I Didn't Have You' (2001), 'We Belong Together' (2010) and 'Let it Go' (2013) won an Oscar for Best Original Song. 'Pinocchio' (1940), 'Dumbo' (1941), 'Mary Poppins' (1964), 'The Little Mermaid' (1989), 'Beauty and the Beast' (1991), 'Aladdin' (1992), 'The Lion King' (1994), 'Pocahontas' (1995) and 'Up' (2009) won the Oscar for Best Original Score. The Oscar for Best Animated Feature has gone to 'Finding Nemo' (2003), 'The Incredibles' (2004), 'Ratatouille' (2007), 'Wall-E' (2008), 'Up' (2009), 'Toy Story 3' (2010), 'Brave' (2012), 'Frozen' (2013), 'Inside Out' (2015), 'Zootopia' (2016) and 'Coco' (2017). 'Who Framed Roger Rabbit' (1988) and 'Toy Story' (1995) both won an Oscar for Special Achievement. Academy Awards after Walt Disney’s death were given to The Walt Disney Company or to studios, such as Pixar and Touchstone, owned by them.

Disney won an Emmy Award (1956) for Best Producer of a Film Series. On 8 February 1960, he became the first animator to receive a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. In 1978, Mickey Mouse was the first fictional character to receive a star on the same walk. Other Disney characters with a star there are Snow White (1987), Donald Duck (2004), Winnie the Pooh (2006), Tinker Bell (2010) and Minnie Mouse (2018). Even Disneyland was awarded a star in 2005. Walt Disney posthumously won a Winsor McCay Award in 1975. Disney is also a member of the Television Hall of Fame (2006), California Hall of Fame (2006) and Anaheim Walk of Stars (2014).

The Walt Disney Company has the most entries included in the United States National Film Registry, where films are inaugurated for their "cultural, historical and aesthetical significance". 'Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs' was added in 1989, followed by 'Fantasia' in 1990, 'Pinocchio' in 1994, 'Steamboat Willie' in 1998, 'The Living Desert' in 2000, 'The Three Little Pigs' in 2007, 'Bambi' in 2011, 'The Old Mill' and 'The Story of Menstruation' (1946) in 2015, 'Dumbo' in 2017, 'Cinderella' in 2018, 'Flowers and Trees' in 2021 and 'The Lady and The Tramp' in 2023. Films made after Disney's death have been entered too, such as 'Beauty and the Beast' in 2002 , 'Toy Story' in 2005, 'Who Framed Roger Rabbit?', 'The Lion King' in 2016, 'Wall-E' in 2021 and The Little Mermaid' in 2022.

Disney added a Chevalier in the Légion d'Honneur (1935), Officer d'Académie (1952), Audubon Medal (1955), Presidential Medal of Freedom (1964) and posthumous Congressional Gold Medal (1969) to his trophy list. In 1980, a dwarf planet was named after Walt Disney and in 1995, an asteroid named after Donald Duck.

Legacy and influence

Walt Disney is one of the few film creators from the Golden Age of Hollywood to still be a household name. No other cultural icon has such global impact. Millions of people have been converted to animation thanks to his achievements. Already during his lifetime, dozens of film studios, both in Hollywood and elsewhere around the world, tried to start their own animation department and copy his techniques. In the early decades, there was still a degree of mystery on how Disney achieved certain technical effects, which led to many aspiring animators writing to the company for advice. Animation aside, Disney is also the most influential cineast of all time. Right from the start, his animated features were the first, and for a long time, the only animated films included and discussed in many film history books and lists of the "greatest films of all time." They had a strong impact on many family and children's films.

But Disney's influence goes even further. The Walt Disney Company is the oldest entertainment concern to still be a dominant force in our present-day media. They managed to keep hundreds of films, characters and other associated merchandising in the public picture for more than a century. All around the world, there are barely places where people aren't in one way or another exposed to his franchises. Even if they never saw any of the original cartoons or films his reputation is based on. Several creators of other multi-million dollar franchises have deliberately sold the rights of their work to Disney, since it would guarantee their work to remain in the public eye, even after their deaths. Many companies still study and use Disney's marketing techniques. His theme parks keep attracting huge crowds. Disney's seemingly eternal media (over)exposure also make the comics based on his characters among the most enduring and widely read comic franchises in the world. When Uncle Walt was still alive, many comic artists wrote to him, either to work for him, or to ask whether he could adapt their characters into an animated short or feature. Even after his death, countless artists have received well-paid jobs writing or drawing comics for his company. It easily makes him the most influential comic creator on the planet.

Disney also had a strong impact on how we look at animals. While he certainly wasn't the first, nor only artist to anthropomorphize animals, his company took it to another level. Thanks to his films, people regard animals with a far more sympathetic, compassionate eye than in previous eras. Pictures like 'Bambi' and '101 Dalmatians', for instance, have been credited with turning many people against game hunting or fur trade.

Some of Disney's famous adult admirers include Idi Amin, Walter Benjamin, Charlie Chaplin, Sergej Eisenstein, Elizabeth II, George VI, Jim Henson, Hirohito, Kon Ichikawa, Michael Jackson, Elton John, Roy Lichtenstein, Paul McCartney, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Steven Spielberg, Sun Ra and Andy Warhol. In the United States, Disney is widely regarded as a national hero. When Time Magazine picked out the 100 Most Influential People of the 20th Century he was the only cartoonist to make the list, but added to their category "Icons of Business", rather than the “Cultural Icons” category. Monte Beauchamp included Disney in his book 'Masterful Marks: Cartoonists Who Changed The World' (Simon & Schuster, 2014), where the cartoonist's life story was adapted in comic strip form by Larry Day.

In a 1954 interview, Disney was once asked what he considered his greatest achievement and answered that he was proud of being able to establish a successful company and keep it running. But he always reminded everybody: "It all started with a mouse."

Walt Disney, photographed in 1951. Photo credit: Profimédia.

Books about Walt Disney

Countless books have been written and published about Walt Disney and his studio. 'Disney Animation: The Illusion of Life' (Abbeville Press, 1981) by Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston is highly recommended for featuring marvelous original artwork, storyboards, atmospheric sketches of many classic Disney pictures, along with technical advice by the former Disney animators. Much unique artwork can also be seen in the Walt Disney Family Museum, which opened its doors in San Francisco, California, in 2009.

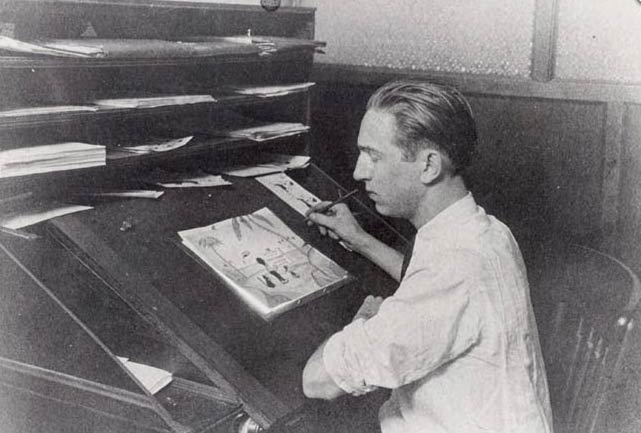

Walt Disney at his drawing board, 1922.

"All our dreams can come true -

if we have the courage to pursue them."

- Walt Disney