William Randolph Hearst, portrayed by W.A. Rogers, Harper's Weekly, 11 January 1902. The dinosaur references Frederick Burr Opper's dinosaur from his comic strip 'Our Antediluvian Ancestors', which ran in Hearst's papers and was set in Cliffville, subject of the article 'Latest News From Cliffville: the Dinosaur Has Swallowed Adam', which Rogers' cartoon illustrates. The cartoon also inaccurately depicts Hearst as a smoker.

William Randolph Hearst was a U.S. newspaper and magazine publisher who was already a legend during his lifetime. As founder of Hearst Communications (1887), he created the largest periodical empire in the world. The famous billionaire was a controversial man, whose papers frequently published smear campaigns, gossip and fabricated stories. His power was so strong that he could influence public opinion and both build and break careers. While Hearst never wrote or drew a comic strip in his entire life, he and Joseph Pulitzer both played an important part in industrializing the medium. Hearst published various daily comics in his papers. Those he didn't own, he tried to buy out. He was one of the pioneers of the Sunday color comics supplement and co-founder of King Features Syndicate (1915), one of the most widespread comics distribution networks in the world. Hearst was an important patron to many young artists. He not only launched their careers, but actively promoted their comics and gave them the chance to continue their series for decades. Thanks to his efforts, all rival newspapers in the world had to have their own comic pages. Yet even here Hearst's actions had a darker side too. He fought many legal battles over copyright issues, not all of them fairly. Even cartoonists under his contract didn't always benefit to the fullest from the income garnered by their creations, in sharp contrast with Hearst himself. And while the tycoon popularized comics among general audiences, he also unwillingly gave it a bad reputation. His aggressive merchandising led to overexposure and banality of certain series. As long as comics kept making money they were continued for decades, rather than end on a high note. This practice only increased the medium's largely undeserved reputation for "lack of quality" and the familiar phenomenon of "seasonal rot" or "zombie comics."

William Randolph Hearst.

Early life

William Randolph Hearst was born in 1863 in San Francisco into a millionaire's family. His father was mining tycoon and U.S. senator George Hearst. From an early age, young William Randolph had a cozy and luxurious life. Everybody expected him to follow in his father's footsteps. Yet the young man eventually went into the newspaper business. He studied journalism at Harvard College and took inspiration from publisher Joseph Pulitzer, who would later become one of his most bitter rivals. However, the young student was thrown off campus for partying and playing too many pranks.

The San Francisco Examiner

On 4 March 1887, 23-year old Hearst heard that his father owned a newspaper, the San Francisco Examiner. He had gained it as repayment for a gambling debt and done little to nothing with it afterwards. William Randolph Hearst put the paper entirely to his own hands. He hired famous reporters such as Ambrose Bierce, Jack London and Mark Twain and increased The San Francisco Examiner's investigative journalism. Hearst bought more advanced printing equipment. The lay-out became more lavish, banner headlines were added and the articles were livened up with more photographs, cartoons and illustrations. One of his early cartoonists was Homer Davenport. Much like Pulitzer, Hearst thrived on sensationalism. Facts were twisted to make stories more spectacular. All these tactics worked and in a few years, the San Francisco Examiner became one of the best selling newspapers in the country. Hearst's fame and wealth soon vastly eclipsed his father's. In 1909, the headquarters of the San Francisco Examiner received their own skyscraper building, named the Hearst Building.

The New York Morning Journal

In 1895, Hearst bought another newspaper: The New York Morning Journal, originally founded by Albert Pulitzer, brother of Joseph Pulitzer. When Hearst purchased it, the publication was deeply in the red. Much like with The San Francisco Examiner, Hearst boosted up the paper's sales by sensationalizing headlines and hiring talented writers such as Stephen Crane, Julian Hawthorne and James J. Montague. In 1901, the morning edition of The New York Journal was retitled The New York American.

Expansion

In 1900, Hearst established his first publication bearing his own name: Hearst's Chicago American. Three years later he launched The Los Angeles Examiner (1903) and a magazine for automobile enthusiasts: Motor (1903). A Bostonian paper, The Boston American (1904), was launched a year later. By now Hearst was rich enough to just buy successful publications and make them part of his ever-growing media conglomerate. He acquired Cosmopolitan in 1905 and in 1911 Good Housekeeping and World To-Day (in 1912 renamed Hearst's Magazine, in 1914 Hearst's and eventually in 1922 Hearst's International). The media tycoon went on to add The Atlanta Georgian (1912, sold in 1939), San Francisco Call (1912), San Francisco Post (1913), Harper's Bazaar (1913), Puck (1916, closed down in 1918), Boston Advertiser (1917, closed in 1929), Washington Times (1917, sold in 1939), Chicago Herald (1918, renamed Herald-Examiner), Detroit Times (1921), Boston Record (1921), Milwaukee Telegram (1921), Wisconsin News (1921), Seattle Post-Intelligencer (1921), Albany Times-Union (1922), Rochester Journal (1922), Syracuse Telegram (1922, which he sold again three years later), The Washington Herald (1922, sold in 1939), Baltimore News (1923), San Antonio Light (1924), New York Mirror (1924, sold again four years later), Town & Country (1925), Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph (1927), Omaha Bee (1929, sold in 1937), San Francisco Bulletin (1929), Los Angeles Evening Express (1931, which became the Herald Express), Baltimore Post (1935) and the Milwaukee Sentinel (1939).

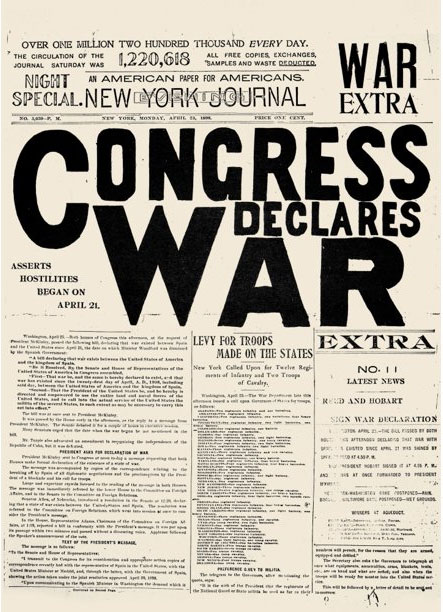

The start of the Spanish-American War, 25 April 1898.

Controversy: gossip and slander

Hearst and Pulitzer owed much of their success to publishing and creating gossip stories. Their papers were notorious for spicing up news events by outright fabricating details, pictures and even entire stories. Since the circulation of their papers was so widespread they had a strong impact on U.S. public opinion. Hearst and Pulitzer went through great lengths to credit or discredit people. Friends and business partners were praised, while people outside their business interests were slandered beyond belief. Hearst's inflammatory editorials, propaganda-like cartoons and forged documents and photographs influenced many readers. On 10 April 1901, The New York Journal attacked U.S. President William McKinley by suggesting murder: "Institutions, like men, will last until they die; and if bad institutions and bad men can be got rid of only by killing, then the killing must be done." On 3 June, the paper once again advocated murder when Hearst's editorial suggested that "assassination can be a good thing (...) The murder of Lincoln, uniting in sympathy and regret all good people in the North and South, hastened the era of American good feeling." Three months later president McKinley was murdered by Leon Czolgosz, which led many Americans to accuse Hearst of "inspiring and justifying" the assassination.

Racism and other prejudices

Hearst's campaigns against Communism, Hispanics, Filipinos, Russians and Asians also threw oil on the fire and confirmed many readers' prejudices against these people. The tycoon had a lifelong hatred of Hispanic people and minorities, particularly when he lost 800,000 acres of timberland in Mexico when local revolutionary Pancho Villa conquered it.

Cartoon by Leon Barritt spoofing the rivalry between Hearst and Pulitzer, both in Yellow Kid outfit claiming "ownership" of the war (Vim magazine, June 1898).

War mongering

Hearst's prejudices became particularly clear in 1898 when the military ship USS Maine exploded and sank in the harbor of Havana, Cuba. At the time Cuba was still a Spanish colony and thus many assumed it had been a military attack. In reality the explosion had been merely an accident on board. But Hearst and Pulitzer's papers claimed that Spain had attacked the ship. They heated up anti-Spanish sentiments and strongly advocated sending U.S. troops to the conflict with screaming headlines like: "War? Sure!". Eventually the Spanish-American War (1898) broke out. During the three months of warfare, Heast and Pulitzer's papers became propaganda organs, twisting facts to justify the war and sell more copies. After Spain was defeated, the Treaty of Paris (1898) gave the United States control over the former Spanish colonies Puerto Rico, Guam, Cuba and the Philippines. Although they were technically not U.S "colonies", the treaty did allow a strong U.S. military and economic presence in these countries. The often repeated story that Hearst sent illustrator Frederic Remington to Cuba with the instruction: "You furnish the pictures and I'll furnish the war" is nowadays considered an urban legend, but still gives an idea of how many people felt about Hearst and Pulitzer's involvement in this war.

Newspaper boy strike

Although Hearst was phenomenally wealthy, his newspaper delivery boys received very low wages. Between 18 July and 2 August 1899, Hearst and Pulitzer's delivery boys went on strike in an united effort to force higher payments. In a time when promotion in the streets was still very important to motivate people to buy newspaper copies, the strike hurt both newspaper tycoons financially. Particularly Pulitzer saw his circulation drop from 360,000 papers a day to 125,000. Many regular people sympathized with the young newsboys and refused to buy any copies from Hearst and Pulitzer's papers. In the end the boys' demands were accepted and their earnings doubled. The 1899 Newsboys' Strike inspired the comic characters 'The Newsboy Legion' by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby. They debuted in issue #7 of Star-Spangled Comics (April 1942).

Header for the Sunday comics supplement of the Chicago American of 9 December 1900, drawn by Frederick Burr Opper.

Comics

Hearst had a strong love for comics. In fact, the "funny papers" were one of his major selling points. People loved to laugh at the daily antics of their favorite characters and/or were interested how a certain storyline might develop. The earliest American cartoon feature built around recurring characters debuted in 1892 in Hearst's San Francisco Examiner: Jimmy Swinnerton's 'The Little Bears' (1892-1901). During its early years, it was mostly a one-panel cartoon and only received its proper title in 1895. Still, the series is the first example of a "funny animal" comic in the United States. When Hearst noticed that Joseph Pulitzer's New York World had a Sunday comics supplement in color, he too introduced one in his own paper, The New York Morning Journal. The shrewd tycoon went so far as to buy Pulitzer's entire staff out.

Hearst also bought away comic artist Richard F. Outcault from The New York World, a newspaper owned by Joseph Pulitzer. In the mid-1890s, Outcault was effectively the most popular newspaper cartoonist in the U.S. His feature 'Hogan's Alley' (1894-1898) was enjoyed by thousands of readers, many who bought newspapers just for this cartoon feature alone. While Hearst now owned Outcault, the rights to the comic's title remained with The New York World, prompting artist George Luks to continue 'Hogan's Alley' there but with differently designed characters. In Hearst's papers, Outcault could continue the same cast of characters but under the different title 'McFadden's Row of Flats' (later 'The Yellow Kid'). This was the first example of a legal battle over a comic strip in history, though the case was never taken to court. Instead, only a legal decision was issued on 15 April 1897 on behalf of the Treasury Department and advised by the Librarian of Congress. Hearst would later buy out another series by Outcault, 'Buster Brown' (1902-1921), which originally appeared in The New York Herald. Outcault retitled his series 'Buster Brown & Tige' in Hearst's papers, while William Lawler continued it under its original name in the Herald. The term "yellow journalism" to describe sleazy and sensational news reports was derived from 'The Yellow Kid' and this bitter rivalry between Hearst and Pulitzer's papers.

Logo of King Features.

King Features

In 1913, Hearst founded his own book publishing business - Hearst's International Library - which in 1919 was renamed the Cosmopolitan Book Corporation and sold again in 1931. However, his most significant contribution to comics history was the establishment of King Features Syndicate on 16 November 1915. It brought all of Hearst's daily entertainment features together into one syndicate, including columns, editorials, games, puzzles, cartoons and comics. King Features also guards their merchandising rights. The name "King" was the literal translation of the first syllable of Moses Koenigsberg's name. Koenigsberg was Hearst's manager and the initiative taker of King Features. Dutch comic legend Marten Toonder once told a funny anecdote about King Features. As a young boy, he felt that "Mr. King Features was the most imaginative and productive comic artist in the world", unaware of what those two words actually stood for. As of today, more than a century later, King Features is still the biggest international comics syndicate. It has distributed and licensed thousands of comic series all over the globe. Though some were syndicated through "second-tier" agencies, such as the International Feature Service and the Premier Syndicate.

A safe haven for comic artists

Hearst actively promoted all the cartoonists in his newspapers. He invested in advertisements, merchandising products and various audio-visual adaptations (stage plays, radio plays, films and animation). The Yellow Kid Magazine, founded in 1897, was the first U.S. comic magazine. Above all, the billionaire created an environment where his cartoonists were financially secure and enjoyed relative creative freedom. As long as they avoided controversy, they were allowed to write and draw what they pleased. Many were therefore able to grow as artists. They could perfect their drawing and narrative skills. They had room to experiment with new gags, artwork, lay-out, storylines and characters. If they wanted to launch a new series, it was perfectly possible. One artist who took full advantage of this was George Herriman. His comic strip 'Krazy Kat' was highly eccentric with punchlines that were lost on most regular readers. In any other newspaper the series would've probably been canceled after a while. But Herriman was lucky that Hearst loved 'Krazy Kat'. The newspaper mogul kept the series running for decades, regardless of what other people said. Without Hearst, 'Krazy Kat' might have never achieved its enduring classic and artistic status among comic fans and fellow cartoonists.

The same can be said about countless other legendary comic artists, who all owe their career to William Randolph Hearst: Nicholas Afonsky, T.S. Allen, Walter Allman, Carl Anderson, Louis Biedermann, Bit (A.K.A. Nándor Honti), Sals Bostwick, Paul Bransom, Clare Briggs, Nell Brinkley, Elliot Caplin, Gene Carr, A.D. Carter, Robert Carter, Oscar Chopin, Billy DeBeck, Rudolph Dirks, Tad Dorgan, Lee Falk, A.C. Fera, Don Flowers, Hal Foster, Rube Goldberg, Chester Gould, Milt Gross, George Herriman, Harry Hershfield, Oscar Hitt, F.M. Howarth, A.C. Hutchison, Jerry Iger, Will B. Johnstone, E.W. Kemble, Benjamin Cory Kilvert, Harold H. Knerr, Albert Levering, Ed Mack, Gus Mager, Myer Marcus, Winsor McCay, Tom McNamara, John Milt Morris, Jimmy Murphy, John Cullen Murphy, Neil O'Keeffe, Frederick Burr Opper, Marjorie Organ, Richard F. Outcault, C.M. Payne, T.E. Powers, Louis Raemaekers, Alex Raymond, Charles Saalburg, Charlie Schmidt, Carl Emil Schultze, E.C. Segar, Otto Soglow, William Steinigans, Cliff Sterrett, T.S. Sullivant, James Swinnerton, Don Tobin, Edgar Wheelan, Gluyas Williams, Doc Winner and Chic Young.

Richard F. Outcault's 'Yellow Kid' advertising for the New York Sunday Journal (1897).

A burden to comic artists

However, Hearst was not a cultivated man. He rarely employed people on the basis of their talent. He merely observed which cartoonists had the most success in other publications. Once he had identified them, he tried to buy them away. They were basically there to attract readers, thus setting the scene for disagreements between newspapers and cartoonists ever since. In the early days the copyright and licensing rights were held by newspapers. Many artists lost their own creations in fierce courtroom fights after they left the paper and wished to take their work with them, like the aforementioned Richard F. Outcault. A similar situation occurred in 1913, when Hearst fired Rudolph Dirks, creator of 'The Katzenjammer Kids', and employed Harold Knerr to continue the series. Dirks sued but once again couldn't get the rights to the original title. He therefore went to The New York World, where he used the same characters under the title 'Hans und Fritz' (later changed to 'The Captain and the Kids'). After Hearst bought away Winsor McCay in 1911, the artist continued 'Little Nemo in Slumberland' under the new title: 'In the Land of Wonderful Dreams', which never matched the beauty or popularity of the original.

While many cartoonists were seduced by higher payments, even the rich and powerful Hearst couldn't always get what he wanted. Envious of the success of Gene Byrnes' 'Reg'lar Fellers', for instance, he ordered one of his own cartoonists, A.D. Carter, to remodel the comic strip 'Our Friend Mush' under a new title, 'Just Kids' (1923-1957), so it would resemble 'Reg'lar Fellers'. He asked the same to Doc Winner with 'Tubby' (1923-1926). Hearst also bought away Larry Whittington so he could create a comic in the style of his 'Fritzi Ritz', which became 'Mazie the Model' (1925-1928). Another time Hearst desperately tried to obtain Harold Gray's 'Little Orphan Annie', but failed. So instead he asked Ed Verdier to create a nearly identical variation: 'Little Annie Rooney' (1929-1966). When Hearst bought away Don Flowers and his series 'Modest Maidens', the comic strip ran in his papers under the different title: 'Glamor Girls' (1945-1968). Alex Raymond's 'Flash Gordon' (1934) was created as an answer to Dick Calkins and Phil Nowlan's 'Buck Rogers', while Raymond's 'Jungle Jim' (1934-1954) competed with Rex Maxon's 'Tarzan'. Charlie Schmidt's 'Radio Patrol' (1933-1950) competed with Chester Gould's 'Dick Tracy'.

Hearst could be quite spiteful. After a falling-out with Edgar Wheelan in 1917, the artist took his series 'Midget Movies' to another paper. Hearst ordered Chester Gould to create a similar comic, 'Fillum Fables' (1924-1929), while Wheelan had further success with 'Midget Movies' (now retitled 'Minute Movies', 1917-1936). Yet a few years later the businessman had his revenge by buying away Wheelan's assistant Nicholas Afonsky. Twice William Randolph Hearst was double-crossed himself. In 1908 he bought Bud Fisher's 'Mutt and Jeff' away from the San Francisco Chronicle, but in 1915 Fisher left Hearst's papers and took his series with him. Since he legally owned the rights to both the title and his characters there was nothing the mogul could do about it. A similar bitter legal battle occurred between Hearst and Harry Hershfield, creator of 'Abie the Agent'. Once again the artist could only use the characters while the series' title remained in Hearst's hands. But this time his new paper wouldn't accept his comic if they couldn't publish it under its original title. Hershfield was therefore forced to create a new comic strip, 'According to Hoyle' (1933-1935), in The New York Herald Tribune. Ironically enough, Hearst was unable to find artists who could mimic Hershfield's graphic style and therefore 'Abie the Agent' was temporarily discontinued in his own papers too. In 1935, Hershfield and Hearst settled their differences and he and 'Abie the Agent' returned to Hearst's papers.

Announcement for the Chicago American's new comics section, on 17 February 1915.

International News Service: Film journals

As a man with a vision, it comes to no surprise that Hearst invested in other media too. In 1909, he established his own movie news series: the International News Service (INS). They specialized in movie journals, the forerunner of our present day TV journals, with the difference that these film journals played in theaters. In the early 20th century, film footage of news events was still very special, since cameras couldn't always record every potential news event. Hearst's newsreel service Hearst Metrotone News (1914-1967) professionalized film journalism and attracted many viewers.

International News Service: Animation

In 1915, Hearst also set up his own animation studio: International Film Service (IFS). At the time, the only actual animation studio had been created by Raoul Barré one year earlier! Hearst naturally bought several people from this company: Gregory La Cava, William Nolan, Frank Moser and even Barré himself were put under his payroll. The IFS studio created animated cartoons based on Hearst's most popular newspaper comics, in the hope of reaching more potential newspaper buyers. Between 1914 and 1919, comics like Frederick Burr Opper's Frederick Burr Opper's 'And Her Name Was Maud' and 'Happy Hooligan', George Herriman's 'Krazy Kat', Walter Hoban's 'Jerry on the Job', George McManus' 'Bringing Up Father', Rudolph Dirks' 'Katzenjammer Kids' , Harry Hershfield's 'Abie the Agent' and Tad Dorgan's 'Judge Rummy' were adapted into animation.

Unfortunately, these films stuck too close to the source material, with characters literally using speech balloons to communicate. Since viewers would have to read this dialogue, all action had to freeze during these scenes. The cartoons disappointed fans of the original comics and failed to impress newcomers. By 1918, the company was already in debt. Even bringing in talented animation director J.R. Bray helped little. IFS eventually went bankrupt. In the decades that followed, Hearst had many of these animated shorts destroyed, because he feared reruns might have a negative effect on his popular newspaper comics and his own reputation. This also explains why not many of these pictures have survived. Historically, IFS is important for creating the earliest animated adaptations of comic strips. The studio was also a career opportunity for many future huge names in the animation industry, such as future Disney employees John Foster, Burt Gillett, Bert Green, Jack King, Isadore Klein, Grim Natwick, George Vernon Stallings, Ben Sharpsteen, and Walter Lantz, the creator of 'Woody Woodpecker'.

Cosmopolitan Productions: Films

Between 1918 and 1938, Hearst owned his own film production company, Cosmopolitan Productions. It served as a vehicle for pictures starring his mistress Marion Davies. He also produced a live-action adaptation of Russ Westover's comic strip 'Tillie the Toiler' (1927). Cosmopolitan Productions was additionally responsible for producing such film classics like 'Show People' (1928), 'Captain Blood' (1935), 'The Story of Louis Pasteur' (1936) and 'Young Mr. Lincoln' (1939).

Radio and TV

Hearst bought his own radio station in 1932, WINS (AM), and in 1947 produced one of the earliest television broadcasts in the United States, 'INS Telenews', for the DuMont Television Network. A year later he bought the TV station WBAL-TV in Baltimore.

Cartoon by Louis M. Glackens for Puck magazine, spoofing Hearst's election campaign (1906). We recognize, in clockwise order, Alphonse & Gaston, Happy Hooligan, the Katzenjammer Kids, Buster Brown and Foxy Grandpa.

Fame and private life

Like many media celebrities, Hearst was one of the most talked about people of his time. At the height of his career, the media tycoon was rich enough to build his own castles and mansions. He filled them with an extravagant collection of paintings, statues, carpets, books and furniture. Many celebrities came to visit him, including politician Winston Churchill, playwright George Bernard Shaw, aviator Charles Lindbergh and Hollywood actors Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks. Walt Disney once had Floyd Gottfredson design a personalized birthday card for Hearst, featuring Mickey Mouse and friends singing 'Happy Birthday' to him.

In the 1910s, Hearst had an affair with actress Marion Davies, while still married to his first wife, Millicent Wilsson. By 1919 they openly lived together and had a daughter: Patricia Lake. Hearst helped Davies launch a Hollywood career, arranging prestigious parts and promoting these pictures in all his papers and magazines.

Political career and opinions

Hearst's ambitions rose when he went into politics. He tried to run for major and later governor of New York and even President of the U.S., but was never elected. As a political observer Hearst lacked the insight and foresightedness he had as a businessman. He favored isolationism and resisted American involvement in both world wars. During the First World War he actually opposed the Allied Forces in his papers, since much of his readers were of German extraction. In 1916, Hearst's International News Service and all his papers were therefore banned in France, the United Kingdom and Canada. Only when the U.S. entered the First World War in 1917 Hearst changed his tune. The business mogul initially supported the Russian Revolution, but later became a staunch anti-Communist, even going so far as to support Fascist dictatorships. He was a fierce opponent of the League of Nations (a forerunner of the UN) and the British Empire. Between 1936 and 1938, his papers led a fierce campaign against marijuana, claiming it led to violence. This laid the groundwork for the American anti-drugs policy to this day.

Part of a cartoon series about Hearst's German sympathies by Clarence Daniel Batchelor for the New York Tribune, 1918).

Downfall

After the 1929 Wall Street Crash, Hearst's media empire was hit hard by the economic crisis. He had to sell many properties or merge certain magazines and papers. Nevertheless he kept spending millions on his prestigious art collection, which led to predictable debts and mortgages. He once had an entire monastery in Spain flown over and rebuilt stone by stone in the U.S. Eventually Hearst was forced to sell most of his antique collection, his entire zoo and had to fire many of his employees. While the tycoon never went bankrupt, he had to pay rent in order to live in his own castle.

Hearst's reputation was further tarnished when he started a neverending smear campaign against president Franklin D. Roosevelt. Originally he had been a supporter of F.D.R., but his opinion changed when Roosevelt announced his "New Deal" policy. These economic measures helped many people get a job, yet Hearst only cared about his own business interests. His papers attacked Roosevelt on a daily basis. Since the president was extraordinarily popular and re-elected four times in a row, Hearst's opinions naturally cost him a lot of readers. He alienated even more people when he openly praised dictators like Benito Mussolini, Adolf Hitler and various tyrants in Latin America. Hearst went so far as to offer them a chance to promote their propaganda in his papers. In 1934, Hearst met Hitler in Berlin, where he was fooled to believe that the Führer had good intentions and was just "misunderstood". In 1936, the famous publisher visited Rome in the hope of meeting Mussolini, but 'Il Duce' was too busy. Yet his mistress Margherita Sarfatti acted as a ghostwriter for Mussolini, which motivated Hearst to give her a column in his papers. The stubborn media magnate remained supportive of Hitler and Mussolini even when it was already clear they were stirring up a new world war. His papers and newsreel service kept defending them.

Hearst as a U.S. Democrat, by Clifford Berryman, 1906. The man complaining that Hearst "takes up too much space" is party member William Jennings Bryan.

Citizen Kane

In 1941, Hearst was outraged once again when he heard that former theatrical director and radio star Orson Welles made a film about him: 'Citizen Kane'. He never saw the picture, but one of his gossip columnists, Hedda Hopper, had attended the preview screening. True to her "profession", she told Hearst that the movie slandered his name. In reality, 'Citizen Kane' was about the fictional newspaper tycoon Charles Foster Kane. Hearst's name was never even mentioned. But the similarities were difficult to deny. Several elements were obviously inspired by Hearst's own life, including his ruthless business policies, huge castle, art collection, mistress, political aspirations, dubious political friends and much of his rise and downfall. Even the mystery word "rosebud" which sets the plot into motion was in fact Hearst's nickname for Marion Davies' clitoris. The tycoon instantly tried to boycott the picture. His personal friends in Hollywood were pressured to keep the film out of circulation and/or buy and destroy the negative. Hearst wanted to ruin Welles' career too. He arranged an underage girl to wait in Welles' hotel room. If the director entered the room the nude teenager would jump in his arms, whereupon a hidden photographer would snap a picture. The plan was foiled when Welles was tipped off by someone who advised him "to not return to his hotel room."

In the end, Hearst didn't need to go through all this effort. 'Citizen Kane' was too ahead of its time. Its non-chronological plot, lack of identifiable characters and downer ending made it unpopular with average viewers. Most of its cinematography was groundbreaking, yet too strange for most people. The film hardly made its money back. Hollywood producers who'd given Orson Welles complete creative control now panicked and started meddling with all his next pictures. Gradually Welles became an outcast in Hollywood. While he did make new films now and then, most were hampered by budget problems. 'Citizen Kane' was not destroyed, but forgotten for about a decade. Hearst lived long enough to see Welles' career go downhill, which satisfied him greatly. In 1951, the legendary newspaper tycoon passed away.

Yet within a few years after his death, 'Citizen Kane' was rediscovered by film critics. Like many foreign artists, Welles' genius was first recognized in France, where his movie debut was hailed as a masterpiece. In the rest of the world the film's reputation grew as well. 'Citizen Kane' gained a following through TV broadcasts and by the 1960s it was widely acknowledged as the greatest film of all time. Today this reputation is still solid, though in 2012 the film magazine Sight and Sound dethroned 'Citizen Kane' and named Alfred Hitchock's 'Vertigo' the best picture of all time. Yet nobody can deny that 'Citizen Kane' remains a milestone in cinematic history. In an interesting side note: Charles M. Schulz deemed it his favorite movie and watched it more than 40 times during his lifetime, even referencing this in a 1973 Sunday page of his comic strip 'Peanuts'.

In an ironic twist of events, the film Hearst tried to suppress is nowadays considered mandatory viewing for any cinephile, film student or film critic. Even more ironic is the fact that Welles is nowadays far more famous than Hearst. The newspaper mogul who ruined so many people's reputations by publishing sensationalized stories now lives on in a fictionalized negative movie portrayal. If people nowadays have heard of Hearst at all, it's mostly through his association with 'Citizen Kane'. Although not all events in the film are direct references to Hearst, many viewers still assume they are. The line between Charles Foster Kane and Hearst has therefore become increasingly blurred.

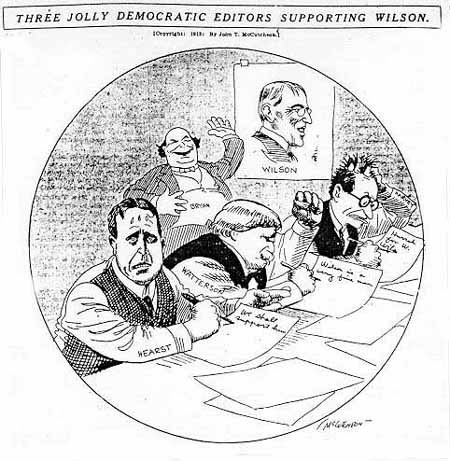

Cartoon depicting William Randolph Hearst, drawn by John McCutcheon.

Legacy and influence

In 1951, after Hearst's death, his second son William Randolph Hearst Jr. (1908-1993) became head of Hearst Newspapers. William Randolph Hearst leaves a complex legacy behind. Much of his business power was used to pursue highly unethical journalistic methods and ruin people's careers. He played a questionable part in evoking the Spanish-American War. His Fascist sympathies and extramarital affair add to a not so pretty picture. On the other hand, the man was also active as a philanthropist. He established the Hearst Foundation (1945) which donates money to good causes and is still active today. His media empire has endured too and shed itself from their association with "yellow journalism". King Features has given hundreds of newspaper comics an international audience and kept them in the popular consciousness, regardless whether some of them might have been more highly regarded if they hadn't continued for so long. Friend and foe cannot deny that Hearst played an important role in comics' worldwide fame, popularity and professionalization. It's therefore fitting that Mort Walker, the last comic artist to be personally greenlighted by Hearst, established a Hall of Fame for comic artists in his Museum of Cartoon Art (1972), naming it the William Randolph Hearst Hall of Fame.

Books about William Randolph Hearst's newspaper comics & King Features

For those interested in the history of King Features Syndicate, the overview book 'King of the Comics - 100 Years of King Features' (IDW, 2015), edited by Dean Mullaney, is highly recommended.

"IF - The Inaugural Dinner at the White House." Hearst amidst "his" characters, cartoon by J.S. Pughe for Puck (29 June 1904). We recognize (clockwise, starting right of Hearst) Carl Emil Schultze's Foxy Granpa, an unidentified cave man, James G. Swinnerton's Little Bears, the police officer and Happy Hooligan from Frederick Burr Opper's series of the same name, Opper's Alphonse and Gaston and Gloomy Gus, The Katzenjammer Kids and Der Captain, another Swinnerton bear, Uncle Heinie, the teacher and Die Mamma from 'The Katzenjammer Kids'.