'Little Johnny and the Teddy Bears'.

J.R. Bray was a U.S. animated film director and producer. During the 1910s and 1920s, he was a pioneer in animation. While fairly obscure today, he still holds historical importance as one of the first people to establish an animation studio, J.R. Bray Productions, and use a factory model to employ it. His signature character, 'Colonel Heeza Liar' (1913-1924), was the second animated character in history around whom a recurring series was created and the first to inspire a comic strip spin-off. The Bray studios additionally pioneered background printing, cel animation and a first attempt at color animation.

Early life and comics career

Joseph Randolph Bray was born in 1879 in Addison, Michigan, as the son of a local clergyman. He studied at Alma College in Michigan between 1895 and 1896, but wanted to be a cartoonist instead. In 1901, he debuted at the Detroit Evening News. Between 1903 and 1904, he contributed cartoons to the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, followed by work for Life, Puck, Judge, Harper's and the McClure Newspaper Syndicate. Some of his work was published in European humorous magazines as well. His comic strip, 'The Quality Kid' (June-September 1913), was obviously inspired by Richard F. Outcault's child characters 'The Yellow Kid' and 'Buster Brown'.

For Judge magazine, Bray drew the series 'Little Johnny and the Teddy Bears' (1907-1909), inspired by the stop-motion sequence in Edwin S. Porter's live-action film 'The Teddy Bears' (1903-1910). Writers for the feature were Robert D. Towne (1907-1908) and Constance Johnson (1908-1909), and in 1909 a landscape format-shaped booklet was published by Reilly & Britton in Chicago. The strip was revived as 'Little Johnny And The Taffy Possums' for a couple of months in 1909.

Among Bray's other comic series were 'Stubby Penn The Reporter' (1905), 'Singing Sammy' (1907), 'Stuttering Sammy' (A.K.A. 'Singing Sammy', 1906-1907), 'Mr. O.U. Absentminded' (1909-1911), 'Mister Monk' (a.k.a. 'Mister Simian', 1912) and 'Die Dackels' (A.K.A.. 'You Gotta Quit Kickin' Dogs Around' or 'You Gotta Quit Kickin' My Dawgs Around', 1912), all distributed by the McClure Newspaper Syndicate.

'Little Johnny and the Teddy Bears'.

Animation career

Bray was mesmerized by the comics and animated shorts by Winsor McCay and John Stuart Blackton. In 1913, Bray made his first animated picture, 'The Artist's Dream' (1913) - sometimes also titled 'The Dachschund and the Sausage' - though he always claimed that he got the idea for it as early as 1908-1909, which has been contested by film historian Donald Crafton, who felt it would be uncharacteristic for Bray or his distributor, Pathé, to withhold a potentially lucrative item for so long. 'The Artist's Dream' is a live-action film which features an artist who is criticized by his boss that his drawing of a dog "has no life to it". When the boss leaves the room, the dog comes alive and eats a sausage, much to the artist's amazement. Yet every time he brings in his boss to see it, the dog returns to its motionless drawing. After a while, the dachshund has eaten so many sausages that he explodes.

The short was such a success that Bray was put under contract by the Pathé Studios to produce more cartoons for them. In order to reach his monthly deadlines, Bray established his own studio in his New York apartment. In 1914, J.R. Bray Productions saw the light. While Raoul Barré was the first person to create an animated studio in history, Bray introduced a factory system which paved the way for all the professional animation studios that followed in the decades beyond. It also explains the nickname Donald Crafton gave him: "The Henry Ford of animation".

Still from 'Colonel Heeza Liar foils the enemy' (1915).

Colonel Heeza Liar

The Bray Studios were also among the first to build a series around one recurring character (the very first was Émile Cohl, who made some cartoons in 1913 based on the popularity of George McManus' 'Bringing Up Father'). In 1913, 'Colonel Heeza Liar' made his debut. The dwarf-sized colonel was loosely based on Rudolf Erich Raspe's Baron von Münchhausen and U.S President Theodore Roosevelt, who was a known wildlife explorer at the time. Several cartoons start out with him bragging about his wildly improbable adventures, which are then told in a series of flashbacks. One of the prime directors on the series was Walter Lantz who, three decades later, would become famous as the creator of 'Woody Woodpecker'. Lantz also directed many episodes of the series 'Dinky Doodle' (1924-1926), about a little boy and his dog, Weakheart. Bray's longest-running animated series also starred a young boy and his dog, 'Bobby Bumps' (1915-1925). Many were directed by Earl Bray and among the first cartoons in which cartoon characters interacted with live-action people. Their surreal nature and cartoony gags make them still an interesting watch today. Paul Terry also produced his first recurring animated character 'Farmer Al Falfa' at Bray's studio in 1916.

Colonel Heeza Liar comics

Many 'Colonel Heeza Liar' cartoons still show the influence of comic strips. Whenever characters say something, speech balloons appear on the screen, for instance. It comes to no surprise that Colonel Heeza Liar was also the first animated character to inspire a comic strip spin-off. Previously it had been the other way around, with many popular newspaper comics being adapted into animated cartoons. But Bray realized the potential of promoting his own cartoons through newspaper comic adaptations and several were drawn between 1916 and 1917. A 'Colonel Heeza Liar' comic series (17 July-26 August 1906) was credited to Bray himself. Earl Hurd also drew a short-lived newspaper comic strip about 'Bobby Bumps', while Paul Terry did the same for 'Farmer Al Falfa'. Louis M.L. Glackens drew a comic strip based on one of their animated shorts, namely 'Greenland's Icy Mountains'. Despite their efforts, only a few newspapers printed them, mostly local ones, such as the Greenville Weekly Democrat in Minnesota, the Perrysville Journal in Ohio and the El Paso Herald in Texas.

Employees

Like all innovators, Bray had to find out things the hard way. He employed several men to help him create his cartoons. Among the notable names who once worked for Bray were Carl Anderson, Leighton Budd, Wallace Carlson, Shamus Culhane, Leslie Elton, Max and Dave Fleischer, Foster Follett, John Foster, Ving Fuller, Clyde Geronimi, C. Allan Gilbert, Louis M. Glackens, Cornell Greening, Milt Gross, Harry Haenigsen, David Hand, Earl Hurd, Jack King, Walter Lantz, Lank Leonard, Sam Loyd, Frank Moser, Bill Nolan, Walter Reed, Clarence Rigby, Paul D. Robinson, George Vernon Stallings and Paul Terry. In the early days, some of his personnel actually came to work with a hangover on Mondays, which prevented them from getting any work done. To reduce the amount of possible distractions, he moved his studio to a farm up the Hudson River and paid everyone on Monday morning so nobody could spend their Friday pay on alcohol the entire weekend.

Animation pioneer work

Bray's studio also pioneered some major inventions. They developed a printing system which etched the backgrounds on paper with zinc. All regular animation on paper could then be traced on these zinc-etched background sheets. If lines didn't match, they were inked over or erased. Another important breakthrough was cel animation, invented by animator Earl Hurd. Characters were drawn on a clear sheet of celluloid, then placed over still backgrounds, which were then photographed. This made it possible to spend less time on redrawing backgrounds and focus all energy on redrawing characters. Cel animation proved to be such a revolution that all other cartoon studios soon made use of it for almost the entire 20th century. Since the rise of CGI in the 1990s, it's no longer the dominant genre.

Patents

Bray was also the first animator to patent all these inventions. In 1914, he and Hurd set up the Bray-Hurd Processing Company, which gave them a monopoly on the animation process. All other animators who wanted to use their techniques had to buy licenses and pay royalties. In a 1915 interview, he claimed that he merely wanted to keep a quality standard and ensure a fair salary for his animators. Bray was even so bold to visit Winsor McCay while he animated his breakthrough picture 'Gertie the Dinosaur' (1914) and pose as a journalist to obtain more inside information, which he later tried to patent without McCay's knowledge or permission. All this naturally didn't make him very beloved among his fellow animators. Many took him to court. McCay won his case against Bray and received a small percentage of the royalties. By 1932, all of Bray's patents expired because he'd failed to improve on them. As a result, every studio could use them without severe financial losses.

World War I

Besides animated cartoons, Bray also produced training films, educational films and documentary films from 1916 on. When the United States got involved in the First World War in 1917, this led to a higher demand for military training films, which his studio provided accordingly. Bray was held in such high esteem by the U.S. Army that he was able to have one of his animators, Max Fleischer, shipped over to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, so he could fulfill his draft service and keep an eye on the production of his films at the same time. In 1956, the U.S. Army department even cited J.R. Bray for "outstanding patriotic civilian service."

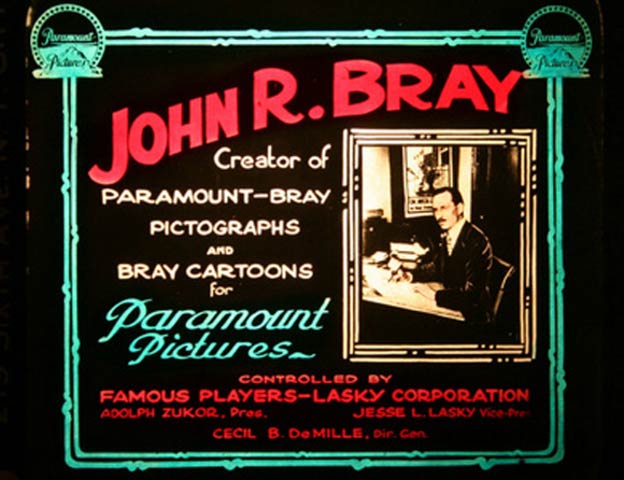

Paramount Pictures glass slide, 1917 (Source: The Bray Animation Project).

Paramount

Throughout the 1910s, the Bray studios were quite successful, only rivaled by Raoul Barré, William Randolph Hearst's International Film Service (1915), Pat Sullivan and the Fleischer Studios. In 1916, Bray signed a contract with Paramount-Famous-Lasky. They produced many animated series based on popular newspaper comics, such as Walt Hoban's 'Jerry on the Job', Richard F. Outcault's 'Bobby Bumps', Johnny Gruelle's 'Quacky Doodles', Milt Gross's 'Ginger Snaps', Rudolph Dirks' 'Shenanigan Kids' (1920), George Herriman's 'Krazy Kat', Frederick Burr Opper's 'Happy Hooligan' and Tad Dorgan's 'Judge Rummy', and also films with new creations like Wallace A. Carlson's 'Otto Luck', 'Goodrich Dirt', 'Us Fellers' and 'Ink Ravings', Carl Anderson's 'Police Dog' and Frank Moser's 'Bud and Suzy'.

Goldwyn Pictures

In 1919, the International Film Service folded and Hearst licensed Bray to continue the studio's activities, which led to most of the staff being transferred to Bray instead. The same year, Bray also broke with Paramount and signed a contract with Samuel Goldwyn to produce three animated shorts a week. The most historically important of these was 'The Debut of Thomas Cat' (1920), which was the first animated cartoon in color. It used the Brewster Color film process, which made use of two different colors. This was 12 years before Walt Disney made 'Flowers & Trees' (1932), the first animated cartoon in full color.

Brayco

In 1928, Bray generally quit producing animated shorts, but continued making educational/commercial documentaries under the name "Brayco" until 1963. A few animated cartoons still premiered in the 1930s. One of them, 'Tea Pot Town' (1936), was released with a comic strip-style coloring book.

Death

J.R. Bray lived a long life and was 99 when he passed away in 1978. Although not as famous as the animation directors who'd benefit from his innovations, he is still praised by film historians for his important and long-lasting contributions to the medium.

From the 'Tea Pot Town' coloring book.

The Bray Animation Project

The Bray Studios' comic strips on the Stripper's Guide