George Herriman was an American comic artist, most famous as the creator of 'Krazy Kat' (1913-1944). Along with Winsor McCay's 'Little Nemo in Slumberland' (1905-1914), it is one of the oldest American newspaper comics still being reprinted, read and enjoyed today. Both 'Krazy Kat' and 'Little Nemo' are early examples of comics with artistic depth. Herriman created his own little universe where a cat (Krazy) is deeply in love with a mouse (Ignatz), even though the rodent is obsessed with throwing a brick at his head. Krazy has the law on his side, because a police bulldog (Offissa Pupp) tries to stop the brick assaults, or failing that, put the mouse in jail afterwards. Herriman was able to elevate this simple running gag with decades of inventive variations. He experimented with lay-outs and ever-changing backgrounds, which paid tribute to the desert landscapes of Arizona he so adored. He also developed his own peculiar language, a mixture of different dialects and spelling, which gave his work a certain poetry. The comic strip is also notable for Krazy being a character of ambiguous gender. This bizarre love triangle between a cat, mouse and a dog was not widely popular in its day, though it did have a following among some intellectuals and members of the art communities. Offbeat and experimental, 'Krazy Kat' returned to public attention with the rise of the underground comix movement in the 1960s, of which Herriman can be considered a forerunner. Of Herriman's other gag comics, the most enduring were 'Baron Bean' (1916-1919) and 'Stumble Inn' (1922-1925), while he also gained fame as the illustrator of Don Marquis' short story book series 'Archy and Mehitabel'. Although research after his death has determined that George Herriman was of mixed race descent, throughout his lifetime he was perceived by most people as white.

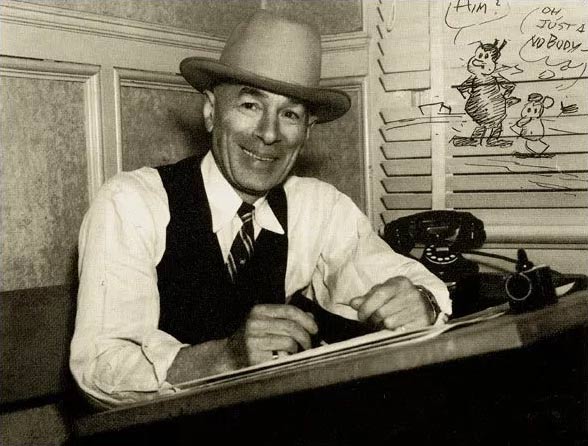

George Herriman.

Early life and ethnicity

George Joseph Herriman III was born in 1880 in New Orleans, Louisiana. His father was a tailor, who moved with his family to Los Angeles when the child was ten. Herriman studied at the local St. Vincent's College (today Loyola High School). The boy was of Creole origin, with Cuban roots. According to present-day standards, this would make him multiracial, and his birth certificate indeed listed him as "colored". Yet as he was light skinned, to most people he could easily pass for white. In a time when racial discrimination was high and African-Americans had a second-class status in U.S. society, Herriman took advantage of this confusion and presented himself as white. Because of his slightly exotic appearance, people nicknamed him "The Greek". Herriman often wore a hat, particularly in publicity photos, that covered and hid his hair, which had a texture associated with black people. Herriman's deception worked extraordinarily well in his lifetime. His death certificate identified him as "Caucasian".

Early cartooning career

After graduation in 1897, George Herriman found a job as assistant-engraver, advertising artist and political cartoonist for The Los Angeles Herald. In 1900, he moved to New York City, where he was a billboard painter on Coney Island, before selling his first cartoons to Judge magazine. On 9 and 29 March 1901, the New York Evening Journal ran two futuristic single-panel cartoons by Herriman under the title 'The Old Song in Future Days', showing the cartoonist's vision of how society will look when aviation becomes common property. That same paper also ran Herriman's first actual comic strip, the short-lived weekday feature 'Maybe You Don't Believe It' (19-26 April 1901), in which he reworked Aesop's fables and gave them happy endings. It features Herriman's first consistent use of speech balloons, as well as his first use of talking animals. Herriman then had a couple of short-lived features published through the McClure Syndicate, such as 'Deacon Skeezicks' (19 January - 6 April 1902) and 'Gazaboo Pete' (AKA 'Turnpike Pete', 23 March - 6 April 1902), but with little success.

Early comic strip from around 1901.

The New York World

In early 1902, Herriman found regular work as a cartoonist, illustrator and comic strip artist with The New York World, a newspaper owned by Joseph Pulitzer. There, he illustrated the daily news columns by Roy McCardell. Since his cartoons met with more favorable reception than his illustration work, Herriman decided to pursue this direction. Until the end of 1903, he had several comic features published in the pages of the New York World. Only a few had a certain longevity. 'Professor Otto and his Auto' (30 March - 28 December 1902), a Sunday comic about a reckless driver, ran for nine months, just like 'Acrobatic Archie' (13 April 1902 - 25 January 1903), starring a boy who worked in the gym to impress his girlfriend, but just causes accidents along the way. Lasting 11 months was a front page full-color strip, 'Two Jollie Jackies' (11 January - 15 November 1903), about two sailors who always looked for kicks, but only found trouble.

'Mrs. Waitaminnit' (30 September 1903).

Most Herriman features of the 1900s and 1910s only lasted a short amount of time. On 19 January, 16 February and 23 February 1902, the New York World printed three episodes of Herriman's strip about the African-American musician 'Musical Mose'. Inspired by Richard F. Outcault's 'Poor Li'l Mose', Herriman's Mose was a walking black stereotype who tried to pass himself off as somebody from another ethnicity, but his hoax was always revealed. The running gag was apparently too one-note to hold the audience's interests, because Herriman abandoned it after only three episodes. Given he also pretended to be a different race than his own, this self-mockery was perhaps a bit too risky.

On 6 September 1902, George Herriman took over the World's western comic 'Lariat Pete' - drawn previously by John Campbell Cory and Daniel McCarthy - which found itself already out of bullets on 15 November. This comic is notable for featuring a prototypical version of Krazy Kat, namely a black feline with a ribbon. 'Mrs. Waitamminit' (15 September -13 October 1903) revolved around the gimmick of a woman who was "always late". Another comic, 'Little Tommy Tattles', about a boy whose honesty got his parents into trouble, only lasted two episodes, printed on 5 and 8 October 1903.

'Major Ozone's Fresh Air Crusade' (1906).

The New York Daily News & World Color Printing

By early 1904, George Herriman had left the New York World and joined The New York Daily News, a newspaper published by Frank Munsey (unrelated to the present-day Daily News, which was founded in 1919). The paper had just shifted its five-cent Sunday paper to Saturdays, and Herriman was offered the opportunity to become its star cartoonist. His illustrations appeared in almost every section of the newspaper, from editorial to sports, including the 'Bubblespikers' column by Walter Murphy. His first comic feature for the Daily News was 'Major Ozone's Fresh Air Crusade' (2 January - 23 October 1904), starring a major craving for clean, healthy air - almost 70 years before environmentalism became a social issue. The character expressed himself in poetic language, which became one of Herriman's trademarks. Herriman's second creation for the Saturday paper was 'Bud Smith, The Boy Who Does Stunts' (13 February - 29 May 1904), about a little trickster boy. In the New York Daily News, Herriman also attempted his first domestic sitcom, 'Home Sweet Home' (22 February - 4 March 1904).

Both 'Major Ozone' and 'Bud Smith' gained national readership when they were picked up by the World Color Printing Company, the syndicate of the St. Louis Star. However, Herriman's tenure with the financially troubled Daily News came to an end after only a couple of months, around April 1904. In June 1905, Herriman moved back to Los Angeles, California, where he resumed his activities for the World Color Printing syndicate. He restarted both 'Major Ozone' (10 September 1905 - 14 October 1906) and 'Bud Smith' (29 October 1905 - 19 November 1905), before merging the latter with 'Grandma's Girl', a comic strip he took over from Charles H. Wellington, about a young girl who enjoys the company of her grandmother and whose pets are able to talk. Between 26 November 1905 and 6 May 1906, the combined feature ran under the title 'Grandma's Girl, Likewise Bud Smith'.

'Rosy Posy - Mama's Girl' (1906).

Other new Herriman creations for World Color Printing were the two-tiered children's strip 'Rosy Posy, Mamma's Girl' (19 May - 15 September 1906) and 'The Amours of Marie Anne Magee' (11 July - 9 August 1906). After Herriman moved to the Hearst newspapers, 'Major Ozone' was continued by, subsequently, Ray Notter and Clarence Rigby. 'Rosy Posy' was drawn for another three years by an unknown cartoonist signing with "Sterling".

Hearst newspapers

Shortly after leaving the New York Daily News in April 1904, George Herriman was hired as a sports cartoonist for The New York American, one of the Hearst newspapers. Although he only stayed there until June 1905, when he moved to California, it proved to be instrumental to his career. He met many cartoonists who would influence his style, namely Tad Dorgan, Bud Fisher, Frederick Burr Opper and James Swinnerton. But most of all, he met the publisher who would become a supporter and fan for the rest of his life, William Randolph Hearst. After his California stint with the World Color Printing Company, he returned to Hearst. From the summer of 1906, he became the house cartoonist and illustrator of The Los Angeles Examiner, and his comic strips were additionally resold to Hearst's East Coast paper, The New York Evening Journal. William Randoph Hearst eventually gave Herriman a lifetime contract with King Features Syndicate - established in 1915 - through which Herriman's features were distributed to newspapers throughout the nation.

'Mr. Proones', from the Los Angeles Examiner (17 December 1907).

Mr. Proones the Plunger

One of George Herriman's early Hearst features was 'Mr. Proones the Plunger' (1906), a daily gag comic about an unlucky race track gambler. The term "plunger" was slang for somebody who lost on big wagers. The feature was launched in the Los Angeles Examiner on 7 December 1906, but discontinued on 26 December of that year. Mr. Proones was perhaps a bit too similar to Clare Briggs' 'A Piker Clerk' (1903-1904), which also starred a man betting on horse races. Interestingly enough, Bud Fisher plagiarized elements from both 'A. Piker Clerk' and 'Mr. Proones' for his own "gambling loser" comic 'A. Mutt', launched on 15 November 1907. Mutt had the same mustache, bowtie, dotted shirt and top hat as Proones. On 27 March 1908, Fisher added a sidekick, Jeff, which led to a title change of his strip, 'Mutt & Jeff'. However, according to a 1919 article in The Los Angeles Graphic, George Herriman had previously created a similar character named 'Little Jeff', featured in his sports cartoons: "Herriman (…) ran a Little Jeff series which he later abandoned and Fisher adopted the character as a companion to Mutt. Herriman has never taken credit for Jeff, telling his friends 'Bud got away with Jeff and I didn't, so he deserves all the credit he can get out of it'. I understand Herriman declined the drawing of a substitute Mutt and Jeff series for Hearst'."

Daily strips for Hearst

Appearing only a couple of times in The Los Angeles Examiner were the Herriman strips 'Mayor Harper On Tour' (19-26 April 1907) and 'Preparations for Fiesta' (1-4 May 1907). More enduring was 'Mary's Home From College', a daily strip centering around a pretty young girl. It ran from 19 February 1909 until 4 January 1910, and then briefly from 3 through 27 March 1919. Between 12 October and 19 December 1909, Herriman's 'Baron Mooch' ran as another daily in papers, an embryonic version of his later, longer-running comic 'Baron Bean' (1916-1919). 'Baron Mooch' also introduced a cigar-smoking duck, who later received his own spin-off comic, 'Gooseberry Sprig' (23 December 1909 - 24 January 1910). 'Gooseberry Sprig' is notable for featuring an anthropomorphic animal world, set in Coconino County, Arizona. The same setting, as well as the characters Gooseberry and Joe Stork, would later turn up in 'Krazy Kat'.

'Alexander' strip from 14 November 1909.

Funny Animal comics

As early as November 1906, Herriman made comics focusing on animals. 'Zoo Zoo', a weekday strip printed in The Los Angeles Examiner, starred a white cat who gets his owners into frequent trouble. By December, after only a two week-run, the series was discontinued. Three years later, on 7 November 1909, Herriman returned to the troublesome cat concept with 'Alexander', AKA 'Alexander the Cat' (1909-1910), published in the Sunday comic supplements of the World Color Printing Company. Again, a white fluffy cat caused a lot of mayhem for its owners, Charles and Leila. Herriman left 'Alexander' on 9 January 1910. From 6 February until 6 March 1910, the series was continued by an unknown artist who signed with the pseudonym "Bart" (Allan Holtz of Stripper's Guide is certain that this was neither Charles Bartholomew, nor Donald Bartholomew). Clarence Rigby was the final artist of the 'Alexander' feature, from 13 March 1910 until the final episode was printed on 2 April 1911. Still at World Color Printing, Herriman's first genuine "funny animal" comic was 'Daniel and Pansy', though it only lasted two weeks, between 21 November and 4 December 1909. It starred a sneaky fox, Daniel, and a dumb, gluttonous pig, Pansy.

Debut of Krazy Kat and Ignatz the Mouse in 'The Dingbat Family', 26 July 1910.

The Dingbat Family

In 1910, George Herriman was called back to New York City to join the art staff of the New York Evening Journal. On 20 June, the paper also debuted Herriman's first new comic of the decade, the gag strip 'The Dingbat Family' (1910-1916). The series revolves around a family who live in a New York City apartment, The Sooptareen Arms. The father, E. Pluribus Dingbat, and his wife, Minnie, have three children: Cicero, Imogene and a nameless baby. At first, the series was a typical family sitcom. Soon, however, The Dingbats started to complain about their nosy neighbors upstairs. Although these obnoxious people are often the point of discussion, Mr. Dingbat had never actually met them. They are never home, or at least they never answer the door. In some gags, Mr. Dingbat tries to spy on them, in others he brings in policemen, detectives, hypnotists and even outright criminals to get revenge on these mysterious upstairs noisemakers. All his plans fail, leaving their identity a complete mystery. Even the readers never saw a glimpse of them, making them one of the first examples of invisible characters in a comic strip. After a month, on 10 August 1910, the series' title was fittingly changed into 'The Family Upstairs'. When the entire apartment building was demolished on 15 November 1911, The Dingbats were forced to move out, but they at least got rid of their nuisance neighbors. From that moment on, the original title, 'The Dingbat Family', was brought back and stayed in vogue until the final episode was printed on 4 January 1916. Another obscure and short-lived daily comic, 'The Mysterious Family Next Door' (1922), by Monte Crews, followed the same running gag.

Krazy Kat

'The Dingbat Family' (1910-1916) might have been a minor footnote in Herriman's bibliography, if it weren't for the fact that it introduced Krazy Kat and Ignatz Mouse. On 26 July 1910, the Dingbats' housecat was ambushed by a mouse. The rodent threw a pebble at its head, leaving the poor feline hurt and confused. Although it was just a tiny visual gag at the bottom portion of the comic, Herriman brought the animals back in later episodes, and their antics became a running gag. On 14 October of that year, the cat was first named Krazy Kat. On 28 October 1913, the couple received its own spin-off comic, 'Krazy Kat' (1913-1944). By then, Krazy and Ignatz were removed from their original domestic setting and put in a desert full of anthropomorphic animals. Some secondary characters were recycled from Herriman's previous comic 'Gooseberry Sprig', such as Gooseberry Sprig and Joe Stork. Others were new, like the brickmaking dog Kolin Kelly, the female duck Mrs. Kwakk Wakk, the Chinese laundry owner Mock Duck, the ostrich Walter Cephus Austridge, the bearded bee Bum Bil Bee and the Hispanic coyote Don Kiyote (whose name is a pun on the literary character Don Quixote). The most significant new cast member was the bulldog "Offissa Bull Pup", who works as a police chief. Herriman also kept the basic running gag from 'The Dingbat Family', in which Ignatz conks Krazy in the head with a brick.

Distributed to newspapers by King Features Syndicate, 'Krazy Kat' ran almost uninterruptedly for 31 years, until the author's death in 1944. For only about ten weeks in 1938, when Herriman underwent a kidney operation, the newspaper relied on reprints rather than original material. A Sunday page was added on 23 April 1916, and from 1935 on, this feature series was printed in color.

Krazy Kat - Concept and analysis

On the surface, 'Krazy Kat' seems to have an easy concept. Krazy Kat is a naïve black cat who is hopelessly in love with the mean-spirited mouse Ignatz. His desire remains unrequited, since Ignatz doesn't want anything to do with Krazy, beyond hurling a brick at his head. Luckily, his actions seldom go unpunished. "Offissa" Bull Pupp usually takes Ignatz into custody immediately afterwards. Herriman rarely strayed from this basic set-up, yet 'Krazy Kat' is a textbook example on how to take a running gag and keep presenting it in clever variations. Sometimes Ignatz is unable to go through with his plan because Offissa Pupp arrests him beforehand. In other cartoons the brick gag is just a tiny detail in one of the frames, while the plot is about something completely different.

Over the years, the relationship between the three main cast members has been the subject of many analyses. Their repetitive love triangle has been interpreted as an allegory for the absurdities of relationships. Krazy loves Ignatz, but doesn't understand that the mouse hates him. Bull Pup has a soft spot for Krazy, but the cat pities "poor" Ignatz more. Krazy and Bull Pup keep romanticizing the object of their desire, even though it could never turn out into a healthy relationship. After all, Ignatz constantly abuses Krazy, while Pupp is forced to rescue Krazy, since the cat can't stand up for himself. It's a vicious circle, where characters chase dreams but never get anywhere.

The characters have also been interpreted from a LGBT perspective. It is never clarified whether Krazy is male or female. 'Krazy Kat' features the first known gender fluid character in the history of the comic strip. In some episodes Krazy is referred to as a "he", while in others he is called a "she". The love dynamic between the trio is present throughout the entire series, regardless of Krazy's gender in any given strip. Offissa Pupp's soft spot for Krazy appears at times to be more than just sympathy. It is astounding that the nature of these relationships are left so open for interpretation. Given the era this comic was created in, and publisher William Randolph Hearst's ultraconservative ideologies, it is even more remarkable.

Interviewed in January 2012 at the Cité Internationale de la Bande Dessinée et de l'Image, Art Spiegelman gave other examples of angles from which 'Krazy Kat' can be interpreted. Some intellectuals see the comic as a political metaphor, where Ignatz is an anarchist, Bull Pup the Fascist arm of the law and Krazy liberal democracy. A psychological view regards Bull Pup as the Super-Ego, Ignatz as the Ego, Krazy as the Id and the brick as sexual activity. Spiegelman compared 'Krazy Kat' to a Cubist painting, which can also be interpreted from different viewpoints.

And then there is the autobiographical element, where the entire comic seems to be a self-reflexive commentary on Herriman's own life and the formula of his own comic strip. In short, anyone can appreciate 'Krazy Kat' on a different level.

Krazy Kat - Atmosphere

While 'Krazy Kat' has a relatively simple art style, Herriman had a great sense for atmosphere. He drew desert scenes evoking the American South West, with huge rock formations and cactuses. When 'Krazy Kat' became profitable enough, he even moved back from the East Coast to Hollywood, California, where he was closer to the Arizona desert. Many of his backgrounds were directly inspired by it, most notably Monument Valley and the Grand Canyon. With Coconino County as their homebase, Krazy, Ignatz and Offissa Pup often take time to admire the majesty of nature and philosophize about it. Herriman had a particular flavor for night scenes. Still, the characters' environment is far from realistic. Backgrounds change from panel to panel, even when the characters do not move. Sometimes a house changes into a cactus, or night turns to day between panels. Other times mountains move around and take a different shape, all giving the comic a surreal look.

Krazy Kat - Lay-out

To frame his drawing, Herriman used inventive lay-outs, particularly in the Sunday pages, where he had the opportunity to use an entire page and - from 1935 on - color. The daily 'Krazy Kat' episodes appeared separately from the other strips in the comic section, often running over the length of a page. For his later Sunday pages, Herriman experimented freely with his panel designs. Most comics in the Sunday section used a grid lay-out, allowing the syndicate to remount the panels and offer the comic to newspapers in either a horizontal or vertical format. Herriman's pages all had a completely different structure, making them usable only in a tabloid format. Some panels have no borders, others have a thick black edge around them, or a round shape, making them stand out. In some cases, these graphical experiments are true artistic "tour de forces". An interesting example is a 1918 gag where Ignatz sends out Krazy to run after a huge rock rolling down a hill. Each panel is tilted in a 45-degree angle, adding a strong sense of speed and weight to the boulder rolling downhill. Compared with the actual punchline - Krazy noticing for himself that the proverb "a rolling stone gathers no moss" is true - the artwork in this gag is the real joke.

Krazy Kat - Language

'Krazy Kat' is also praised for its eccentric and poetic use of language. In previous newspaper comics, dialogue was secondary to the images. A true verbal artist, George Herriman's vocabulary in 'Krazy Kat' was cultivated. He spelled words phonetically, sometimes deliberately mispronouncing them, for instance Krazy's sighs "li'l ainjil" ("little angel") and "li'l dahlink" ("little darling"). Some words were influenced by Herriman's own New Orleans dialect, Yat. Others reveal inspiration from African-American slang, Yiddish, French and Spanish. Puns and word play are also prominent. In a 1937 episode, for instance, Ignatz runs away from Offissa Bull Pup and notes: "He will not foil me, that cop". As Pup passes Ignatz, he states: "He'll not fool me, that mouse." The final panel shows Ignatz throwing his brick at Krazy, while the cat says: "He'll not fail me - that dollin'". Although Herriman's language gives the series its own unique charm, it is sometimes difficult to decipher. Readers are often forced to re-read the speech balloons, or even say them out loud, to understand what the characters are saying.

Krazy Kat - Comedy

One thing that makes 'Krazy Kat' stand out among many other comics from the same era, is the offbeat comedy and meta-humor. In a gag printed on 20 April 1921, Ignatz warns Krazy that a red flag means "danger". When Krazy notices such a flag, but ignores the danger and hurts himself, Ignatz asks him why he didn't listen. Krazy replies: "How could I tell it was a "red flag" when it was made with black ink?" Other gags are more absurd. In the 9 May 1919 episode, an elephant passes by, covering the first two panels. In the final panel, Krazy comments: "Gosh, if there had been another elephant, nobody would have knew we was here today", to which Ignatz adds: "This is no place for elephants." Another weird gag, printed on 21 June 1919, has Ignatz' tail get stuck, making his entire body unravel until there's nothing of him left. And when Krazy is punched in the 12 April 1921 episode, he not just sees stars, but an entire rainbow, complete with a pot of gold standing next to it.

Other episodes are almost anti-comedy, as they lack a recognizable punchline. In a 1939 gag, Krazy and Pupp watch a woodpecker shedding a tear while looking at a painting of a tree. Krazy wonders whether the bird is an "ott kritik" ("art critic", also a pun on the word "odd"). Pupp replies: "Yes, but he is also a woodpecker." To which Ignatz just mutters: "Ah-h", ending the page. One of the marvels of 'Krazy Kat' is that Herriman often went beyond throwaway punchlines. His pages often invite the reader to reflect and let the situation sink in, or just enjoy the charming artwork and poetic use of language.

'Krazy Kat', the 'Tiger Tea' storyline (1936-1937).

Krazy Kat: 'Tiger Tea'

While 'Krazy Kat' was a one-page gag comic throughout most of its existence, Herriman once experimented with a longer narrative. Between 15 May 1936 and 17 March 1937, a plotline, later named 'Tiger Tea' by fans, continued for nearly 10 months straight. The familiar "brick throwing" running gag is absent for months until the very conclusion of this tale. The story allowed Herriman to put more emphasis on atmosphere, suspense and even a moral. In 'Tiger Tea', Krazy Kat tries to help a friend, Mr. Meeyowl, to find the mysterious "tiger tea" ingredient that can help him revive his katnip business. The drink gives anyone who consumes it an energy kick as well as tiger stripes. For modern-day readers, this "tiger tea" also brings up associations with drugs and energy drinks (Perhaps the link with marijuana wasn't that unintentional, as Herriman was once photographed holding a joint). Decades later, the 'Tiger Tea' story arc was reprinted by Art Spiegelman in RAW #11 (June 1991).

Animated adaptations

George Herriman's masterpiece was also one of the first comics to be adapted into animated cartoons. The first attempt occurred in 1916 by William Randolph Hearst's own Hearst-Vitagraph News Pictorial and International Film Service, but without Herriman's direct involvement. One of the animators who worked on these productions was L.A. Searl. The 1920 'Krazy Kat' shorts produced by John R. Bray are generally seen as the most respectable adaptation of the source material. Walter Lantz and Jack King were among the animators who worked on Bray's version of Herriman's creations. Bill Nolan, a former animator for Otto Messmer and Pat Sullivan's 'Felix the Cat', also made 'Krazy Kat' cartoons in 1925, in which the character looked more like Felix the Cat. The 1929-1940 'Krazy Kat' cartoons by Charles B. Mintz' studio were the first to use sound, but on the other hand, had even less to do with Herriman's comic and basically imitated Walt Disney's 'Mickey Mouse'. A few decades later, in 1962, a TV cartoon series was made in Czechoslovakia and Australia by Gene Deitch and distributed by King Features. Their scripts were written by Jack Mendelsohn. Despite their low-budget production, the visuals and overall style matched those of Herriman reasonably well.

Daily strips for Hearst

While working on 'Krazy Kat', Herriman launched several other newspaper comics, though none with the same longevity. Between 5 January 1916 and 22 January 1919, Heart's International Feature Service syndicated Herriman's daily gag comic 'Baron Bean' (1916-1919), about an impoverished nobleman and his valet. After that, he created the daily 'Now Listen, Mabel' for King Features, which lasted only a year, from 23 January until 18 December 1919. The main character Mabel Millarky was either named after the cartoonist's wife and his eldest daughter - who were both called Mabel - or based on a popular collection of gag verses with the punchline "Ain't it awful, Mabel?". The pretty Mabel is so attractive that several young men try to seduce her, much to the dislike of her boyfriend, the shipping clerk Jimmie Doozinberry. This leads to several shenanigans and misunderstandings, often ending in the titular phrase.

Us Husbands

The Sunday strip 'Us Husbands' (9 January - 18 December 1926) also lasted barely a year. The comic originally focused on recognizable situations from the perspective of a married man. Much like 'Krazy Kat', there is little consistency in the backgrounds, which tend to change from panel to panel. Shortly after the start, Herriman added smaller "topper comics" to each episode, such as 'A Big Moment in a Little Man's Life' (16 January - 9 May 1926) and 'Mistakes Will Happen' (16 May - 18 December 1926). Like 'Us Husbands', the latter featured a comical take on married life, but set in an anachronistic version of the Middle Ages.

Stumble Inn

The longest-lasting King Features comic by Herriman, other than 'Krazy Kat', was 'Stumble Inn' (30 October 1922 - 9 January 1925). Appearing during weekdays and on Sundays, the gag series is set in an inn, where various people are employed. Uriah Stumble and his wife Ida are the caretakers. Sodapop is their African-American house porter, while Mr. Weewee serves as their French cook. Whenever something suspicious goes on in Stumble Inn, detective Owl-Eye is hired to find out more. Stumble has to tolerate the presence of Joe Beamish, a man who does nothing but sleep in an armchair in the lobby. It's not clear whether he is an employee, a guest or just somebody who wandered in their place and never left.

'Stumble Inn' (Boston American, 12 September 1923)..

'Stumble Inn' was unusual in its format. Most newspaper comics from that era had six daily one-strip black-and-white episodes and one Sunday full-page color episode. 'Stumble Inn', however, had six daily full-page episodes too. This allowed Herriman to use very detailed artwork. However, most newspaper editors weren't interested in a comic that took up so much space on a daily basis. The daily version of 'Stumble Inn' was discontinued on 12 May 1923, not even a half year after the start. The Sunday comic, launched on 9 December 1922, was more suitable for a weekly full-page format and lasted until 9 January 1925. According to Herriman biographer Michael Tisserand, 'Stumble Inn' was beloved by fellow cartoonists E.C. Segar and Bud Sagendorf.

Embarrassing Moments

On 28 April 1928, Herriman took over the daily one-panel comic 'Embarrassing Moments', started by the cartoonist Jack Farr five years earlier. Since then, several other cartoonists have worked on the feature, including Darrell McClure, Billy DeBeck and Ed Verdier. The cartoons depicted people in shameful situations. Herriman felt the cartoons would be funnier if they centered around one specific character. He came up with 'Bernie Burns' and under this title, the strip ran until 3 December 1932. Bob Naylor assisted Herriman on this series.

Archy and Mehitabel

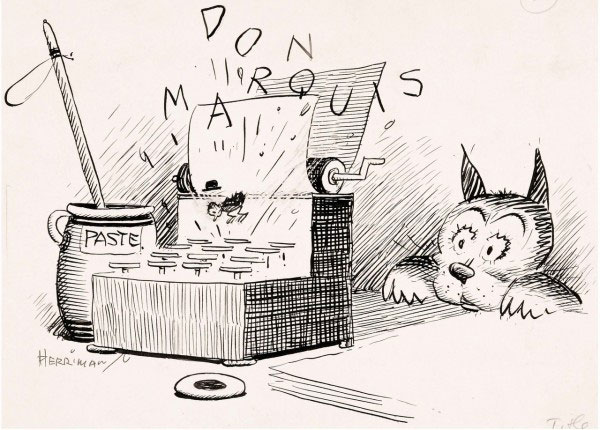

As a book illustrator, Herriman is best known for visualizing Don Marquis' literary characters 'Archy and Mehitabel'. Archy is a cockroach and Mehitabel a cat. Marquis' humorous poems and short stories were supposedly written by the animal duo, satirizing daily life in New York City. However, when 'Archy and Mehitabel' debuted in 1916 in Marquis' column for The Evening Sun, 'The Sun Dial', their stories usually came without illustrations. The feature remained text-only when Marquis moved it to another paper, The New York Tribune, and also when 'Archy and Mehitabel' ran in Collier's magazine. It wasn't until the poems were first collected in the book 'Archy and Mehitabel' (Doubleday, 1927), that Herriman first livened up the pages with his drawings. He was also the illustrator of the book sequels. Novelist E.B. White, famous for 'Charlotte's Web', praised Herriman's artwork in the foreword to 'The Lives and Times of Archy and Mehitabel' (1940). In the 1990s, new unearthed manuscripts of 'Archy and Mehitabel' were released, illustrated respectively by Edward Gorey and Ed Frascino.

'Archy and Mehitabel'.

Final years and death

Herriman was a quiet, gentle man, almost as innocent as his own comics. He was a vegetarian, pacifist and owner of many cats and dogs. Apart from drawing comics, during the 1920s and 1930s, he also wrote gags for Hal Roach's famous comedy studio, responsible for such classic features as 'Laurel & Hardy' and 'Our Gang' ('The Little Rascals'). He got his job through screenwriter H.M. Walker and film director Tom McNamara, both former colleagues from his days at The Los Angeles Examiner, where Walker wrote the sports section and McNamara drew cartoons.

The final decades of Herriman's life were plagued by personal tragedies. In 1931, he lost his wife in a car accident, followed by the untimely death of his 30-year old daughter Barbara, eight years later. After the death of his wife, Herriman began a close friendship through correspondence with Louise, the ex-wife of cartoonist James Swinnerton. Still, his own health also started to decline. Coping with migraine and arthritis, Herriman was additionally diagnosed with liver cirrhosis. In January 1944, he became too ill to reach his deadlines, so between 21 February and 18 March, Bob Naylor filled in on 'Krazy Kat' episodes. Although Herriman returned to the drawing board, he passed away a month later.

The final episode of 'Krazy Kat' was published in the newspapers on 25 June 1944. William Randolph Hearst, who usually assigned other artists to continue long-running comics after the creator's departure or death, decided to discontinue 'Krazy Kat', believing that nobody could replace George Herriman. Apart from that, the series had already lost much of its popularity, with only 35 papers still carrying it. But in 1951, coincidentally the year when Hearst passed away, Dell Comics brought the series back to attention when it released five 'Krazy Kat' comic books, drawn by John Stanley. However, these were more in line with the traditional "funny animal" comics of the time period, and barely reminiscent of Herriman's offbeat style.

Watercolor painting by George Herriman, which is in the Lambiek collection. It was also spoofed by René Windig.

Popularity

George Herriman enjoyed a long and productive career, during which he created many comic features and cartoon panels, of which 'Krazy Kat' is the best-remembered and most reprinted. During its original run (1913-1944), 'Krazy Kat' was already an acquired taste, and never a big hit. Many readers were baffled by it and in other papers it probably wouldn't have lasted long. But Herriman was lucky to have the support of his publisher, William Randolph Hearst. Although Hearst was a conservative man and not publicly known as a cultured soul, something in 'Krazy Kat' appealed to him. He kept his protective hand above his employee's head. Even when readers wrote letters to beg for its cancellation, or when papers dropped the comic without Hearst's approval, he insisted that King Features kept it in circulation. This gave Herriman the opportunity to experiment all he wanted, without ever fearing cancellation. A rare blessing for artists, particularly in the field of comics.

From its early beginnings, 'Krazy Kat' has been an intellectuals' darling. Already in May 1924, essayist Gilbert Seldes praised the comic in his article 'Golla, Golla, the Comic Strip's Art', published in Vanity Fair, as a "thought-out constructed piece of work" which "does not lack intelligence". In his book 'The Seven Lively Arts' (1924), he elaborated even further by devoting a whole chapter to it, 'The Krazy Kat That Walks By Himself'. Other celebrity fans have been painters Joan Miró and Willem de Kooning, actors W.C. Fields, film directors Orson Welles, Fritz Lang and Frank Capra, musicians Michael Stipe (R.E.M.), journalist H.L. Mencken, and novelists T.S. Eliot, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Gertrude Stein, e.e. cummings (who wrote the foreword to a 1946 'Krazy Kat' compilation book), Jack Kerouac and Umberto Eco. U.S. President Woodrow Wilson enjoyed 'Krazy Kat' so much that he never wanted to skip an episode. As stated by Herriman biographer Michael Tisserand, Wilson sometimes had the strip read to him during cabinet meetings. Tisserand also investigated the often repeated claim that Pablo Picasso was a fan of 'Krazy Kat'. He found no source that proved it, except one that confirmed that the famous painter loved Rudolph Dirks' 'The Katzenjammer Kids'. Tisserand concludes that the misunderstanding probably stems from this misquoted source.

Krazy Kat references in pop culture

'Krazy Kat' inspired one of Herriman's colleagues, T.E. Powers, to create a one-shot comic, 'Krazy Kat Herriman Loves His Kittens' (1922), in which the origin of the characters is speculated. In 1921, Herriman's creation also inspired the name of a Washington DC nightclub. In 1922, composer John Alden Carpenter and Adolph Bohm wrote a ballet based on the comic, 'Krazy Kat: A Jazz Pantomime'. Its libretto was illustrated by Herriman, who also wrote the script and designed the costumes. During the first annual Macy's Thanksgiving Parade, held on 27 November 1924, actors walked around dressed as cast members of 'Krazy Kat' and Bud Fisher's 'Mutt & Jeff'. This marked the first appearance of pop culture characters during this particular holiday event. While fictional characters were already turned into huge balloons during the first Macy's Thanksgiving Parade, they were still limited to nursery rhyme characters and Santa Claus. It wasn't until the 6th edition, held on 28 November 1929, that comic/cartoon characters also received this treatment, with Rudolph Dirks' 'The Katzenjammer Kids' becoming the first ones to be honored this way. 'Krazy Kat' was also referenced in the 1934 Laurel & Hardy film 'Babes in Toyland'. In one scene, a cat playing a fiddle (a reference to the nursery rhyme 'Hey, Diddle Diddle') wears a similar ribbon like Krazy around his neck. A mouse resembling Walt Disney's 'Mickey Mouse' (played by a monkey in costume) hits him on the head with a brick. Between 1963 and 1965, the Swedish multimedia artist Öyvind Fahlström used characters from 'Krazy Kat' in a series of works. Ralph Bakshi, who has stated that Herriman is his favorite cartoonist, gave Ignatz the mouse and Mehitabel the cockroach a cameo in his animated film 'Coonskin' (1975). Jay Cantor used Krazy and Ignatz in his novel, 'Krazy Kat: A Novel in Five Panels' (1987). In 1993, John Zorn named a track from his album 'Radio' (1993): 'Krazy Kat'.

Absurd 'Krazy Kat' gag from 21 June 1919.

Krazy Kat revival

During the 1960s and 1970s, when comics became the subject of more serious academic study, George Herriman's status rose considerably. He was praised as an artist far ahead of his time, while 'Krazy Kat' was hailed as one of the earliest comic series with artistic depth. During the same era, the underground comix movement adopted him as a predecessor. After all, Herriman had a very individualistic, non-commercial and somewhat proto-psychedelic style. There is even a subversive streak about 'Krazy Kat', given that the cat is of ambiguous gender and in love with a male mouse. The series found a whole new audience when episodes were reprinted in underground, hippie and adult comic magazines. It also found its way to Europe for the first time, when alternative 1960s magazines like Linus (Italy), Hitweek (The Netherlands) and Charlie Mensuel (France) ran it in translation.

Early reprint collections followed through Nostalgia Press (1969), Street Enterprises (1973) and Hyperion Press (1977). International 'Krazy Kat' book series were published by Real Free Press (The Netherlands, 1974-1975), Futuropolis (France, 1981-1990), Heyne (Germany, 1988) and Ferdydurke (Denmark, 1988). Between 1988 and 1992, Eclipse Comics released nine issues of 'Krazy & Ignatz: The Complete Kat Comics', both in hard and softcover. Between 2002 and 2008, Fantagraphics published the complete 'Krazy & Ignatz' series in luxury volumes, designed by Chris Ware and with introductions by the editor of the collection, comic historian and critic Bill Blackbeard. Herriman's later comic strips 'Stumble Inn' and 'Us Husbands' have been collected in 'Herriman's Hoomins: The Complete Stumble Inn and Us Husbands' (Fantagraphics, 2009). The entire 'Baron Bean' series has been made available in the three-volume book series 'Baron Bean' in IDW's Library of American Comics Essentials (2012-2018). European luxury collections of 'Krazy Kat' were published by Éditions Les Rêveurs (France, since 2012) and Taschen (Germany, 2019).

Heritage research

Over the years, many studies and articles have been dedicated to the life and work of George Herriman. These not only covered his artistic legacy, but also his personal life, and particularly his race. On 22 August 1971, sociologist Arthur Asa Berger published a scoop about the late George Herriman in the San Francisco Sunday Examiner and Chronicle. He had recently done research about the famous cartoonist for the Dictionary of American Biography. In a document from the New Orleans Health Department, it was stated that a man named George Herriman, born in New Orleans in 1880, was black. At first Berger assumed it was a homonym, but Edward T. James, editor of the Dictionary, concluded it was indeed the same man. This revelation put Herriman's work and career in a whole new light. He was presented as the first African-American comic artist in history. Later, more thorough research by Marie Caskey reclassified Herriman as a "mulatto", of mixed African and European ancestry. But since Berger's article was published earlier and reached more readers, the misconception about Herriman's race remained for years.

The revelation that Herriman had a secret racial identity put both the artist and his work in a new perspective. One of his earliest comics, 'Musical Mose' (1903), poked fun at an African-American musician who fails in trying to pass for another ethnicity than his own. In one of his 1910s sports cartoons, a throwaway joke is made about a man selling "transformation glasses", which turn white people into blacks and vice versa. Much of Herriman's eccentric comic strip dialogues are influenced by African-American slang and other ethnic dialects. While 'Krazy Kat' doesn't center on race, in two gags, Krazy and then Ignatz temporarily change color. In one gag (14 July 1918), Krazy's black fur is dyed white, which suddenly makes him attractive to Ignatz. In another gag, Ignatz turns black after falling in a stovepipe, making Krazy instantly lose all interest in him. Another interesting parallel is that Krazy Kat's sexual identity and gender are undefined, while Herriman's own roots were also confusing to the outside world for a long time.

'Krazy Kat'. Part of a drawing George Herriman dedicated to Mrs. Irving C. Valentine, with the words: "Your kind words will long abide with us thine."

Legacy and influence

George Herriman's drawings have been exhibited in museums all over the world. In 2000, he was posthumously inducted in the Will Eisner Award Hall of Fame and in 2013 in the Society of Illustrators' Hall of Fame. His character Ignatz the Mouse also inspired a prize of its own, the Ignatz Awards, established in 1997 by the Small Press Expo.

Walt Disney wrote to Herriman's daughter after her father's death and praised his "contributions to the cartoon business" which were "so numerous that they may very well never be estimated. His unique style of drawing and his amazing gallery of characters not only brought a new type of humor to the American public, but made him a source of inspiration to thousands of artists." In Walt Kelly's 'Pogo', the character Butch the cat often hurls bricks at the dog Beauregard Bugleboy. Robert Crumb called Herriman "the Leonardo da Vinci of comics", while Art Spiegelman felt "Krazy Kat crossed all boundaries between high and low, between vulgar and genteel."

George Herriman remains an inspiration for many comic artists. He is regarded as an "artist's artist", who dared to take creative risks and, with 'Krazy Kat', made a highly personal series. His use of eccentric language in 'Krazy Kat', often peppered with slang expressions, found its way in series like Al Capp's 'Li'l Abner', Walt Kelly's 'Pogo' and E.C Segar's 'Popeye'. Others directly mimicked Herriman's scratchy graphic style, emphasis on surreal dialogue and use of strange anthropomorphic characters who live in a secluded setting, typically a desert like the one depicted in 'Krazy Kat'. Examples are F'murr's 'Le Génie des Alpages', Liniers' 'Macanudo', Bobby London's 'Dirty Duck', Nikita Mandryka's 'Le Concombre Masqué', Patrick McDonnell's 'Mutts' and John Blair Moore's 'Virtual Reality'. Many artists are still inspired by his innovative lay-outs, odd punchlines and ability to use a familiar set-up as a canvas to let his imagination run wild and surprise readers time and time again. Charles M. Schulz once said that 'Krazy Kat' was the level of sophistication he tried to reach with his own comic strip, 'Peanuts'.

In the United States, he influenced Ralph Bakshi, Max Cannon, Al Capp, Robert Crumb, Walt Disney, Will Eisner, Jules Feiffer, Mike Fontanelli, George Frink, Larry Gonick, Edward Gorey, Floyd Gottfredson, Matt Groening (although he liked the drawing style more than the gags), Philip Guston, Sam Hurt, Stephen Hillenburg, Walt Kelly, Jack Kent, Denis Kitchen, Martin Landau, Bobby London, Jay Lynch (whose character Pat in 'Nard 'n' Pat was modeled after 'Krazy Kat'), Dave Manak, Mark Marek, Patrick J. Marrin, Patrick McDonnell, John Blair Moore, Ed Piskor, Cal Schenkel, Charles M. Schulz, E.C. Segar, Dr. Seuss, Andy Singer, Otto Soglow, Gary Panter, Art Spiegelman, Milt Stein, Chris Ware, Bill Watterson and Gahan Wilson. Canadian celebrity admirers are John Kricfalusi and David Turgeon . Together with Luc Giard, Turgeon created the series 'Le Ronron du Krazy Kat', which was a direct homage.

In the United Kingdom, Herriman has admirers among Arch Dale, Hunt Emerson, Stewart Kenneth Moore and Richard Yeend. In France, he counts F'murr and Nikita Mandryka among his fans, while German followers are Hendrik Dorgathen and Andreas Rausch. In the Netherlands, Herriman has been an inspiration for Jos Beekman, Cor Blok, Flip Fermin, Mars Gremmen, Gerrit de Jager, Herman Roozen, Mark Smeets, Jaap Stavenuiter, Joost Swarte, Johannes van de Weert, Windig & De Jong and Menno Wittebrood. In Belgium, he influenced Luc Cromheecke, Lucien Meys (whose gag comic 'Le Beau Pays d'Onironie' was a direct tribute), Gommaar Timmermans, AKA Got and Herr Seele. In Spain, Herriman has been cited as an influence by Alfonso Figueras, in Norway by Jason, in Italy by Annibale Casabianca, Marco Corona, Massimo Mattioli and Giuseppe Scapigliati, in Argentina by Liniers and in South Africa by Zapiro.

Roger Brunel made a sex parody of 'Krazy Kat" in 'Pastiches 2' (1982).

Books about George Herriman

For those interested in Herriman and his art, 'Krazy Kat: The Art of George Herriman' (Abrams, 1986) by Patrick McDonnell and his wife Karen O'Connell is highly recommended. Another must-read is Michael Tisserand's biography 'Krazy: George Herriman A Life in Black and White' (Harper Collins, 2016).

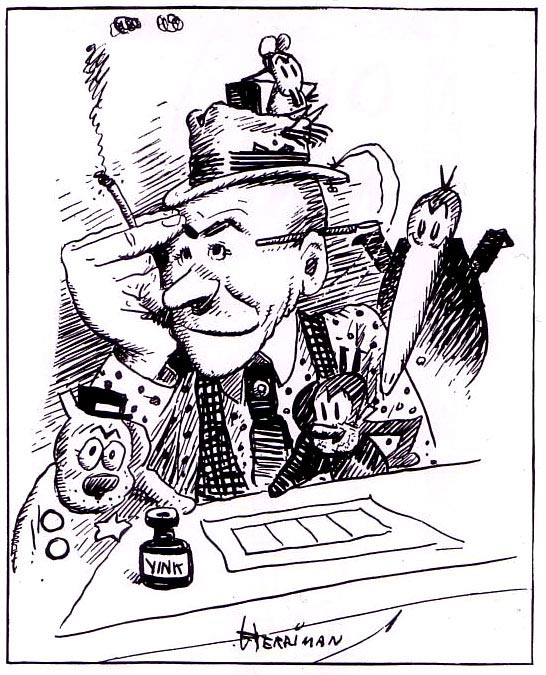

Self-portrait, 1922.