Al Capp was an American cartoonist, most famous for his long-running newspaper comic 'Li'l Abner' (1934-1977). During its heyday, the adventures of Abner and his hillbilly friends were extraordinarily popular, and the series was translated in over 28 languages, adapted into various media and inspired a vast amount of merchandising. Several of its unique words and expressions entered everyday language. 'Li'l Abner' not only perfected the "hillbilly comedy" genre, but also gained praise for its dynamic artwork, imaginative storylines, colorful characters and witty, sometimes biting political-cultural satire. Real-life celebrities frequently received cameos, and current events were regularly referenced. Capp also spoofed politics, economics, advertising and popular media, including the comics medium itself. Together with George Herriman's 'Krazy Kat', Walt Kelly's 'Pogo' and Charles M. Schulz' 'Peanuts', 'Li'l Abner' was one of the first American comics to receive critical praise and popularity among intellectuals. In 1948, Capp also wrote history by winning a trial against his former syndicate and gaining the rights to his own comic creations: besides 'Li'l Abner' also his shorter-lived topper features 'Washable Jones', 'Small Fry' and 'Advice for Chillun'. It gave him unprecedented creative freedom and the power to mass-merchandize his creations. In addition to his own productions, Capp also scripted newspaper comics for Raeburn Van Buren ('Abbie an' Slats', 1937-1971) and Bob Lubbers ('Long Sam', 1954-1962). Al Capp became a media celebrity in his own right, appearing regularly on radio and TV and even hosting his own shows. Towards the end of his career, his legacy was considerably damaged by various sex scandals that have since overshadowed his witty, sophisticated comics, which nonetheless still influence satirists to this day.

Early life

Alfred Gerald Caplin was born in 1909 in New Haven, Connecticut as a son of Latvian-Jewish immigrants. His father, Otto Philip Caplin (1885–1964), was a poor businessman who drew cartoons in his spare time. Capp's younger brother, Elliot Caplin (1913-2000), later became a comic writer as well, best known as the co-creator with Stan Drake of 'The Heart of Juliet Jones' and with Russell Myers of 'Broom-Hilda'. As a child, Alfred Caplin enjoyed reading and devoured both world literature and newspaper comics. He loved novels by Charles Dickens, George Bernhard Shaw, Booth Tarkington, Mark Twain and the plays of William Shakespeare. His graphic influences were Phil May, Wilfred R. Cyr, Billy DeBeck, Rube Goldberg, Milt Gross, Frederick Burr Opper, George McManus, Rudolph Dirks, Cliff Sterrett and Tad Dorgan. Later in his career, Capp also expressed admiration for Ernie Bushmiller.

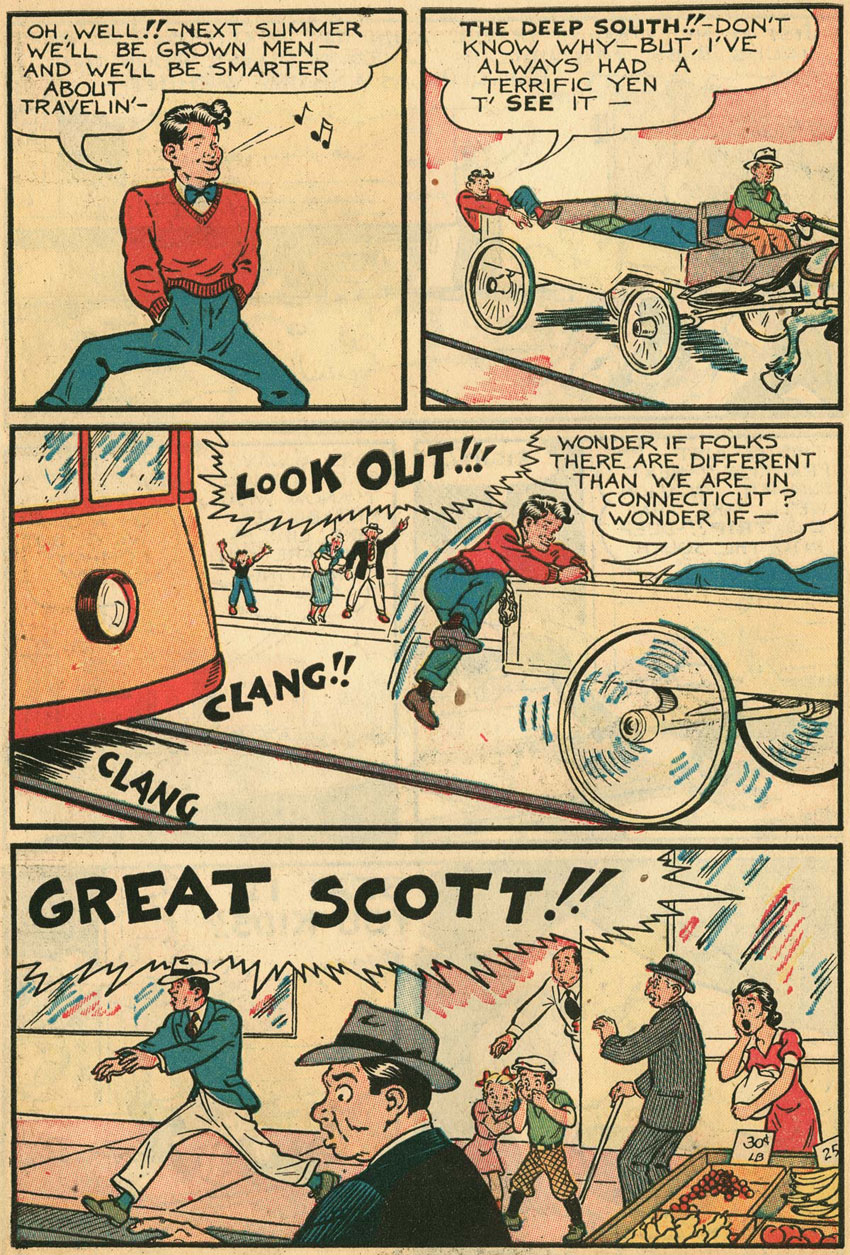

In the partially autobiographical comic book 'Al Capp by Li'l Abner' (1946), Al Capp told about his own childhood accident.

At age nine, Capp was hit by a trolley car and fell into a coma. His left leg was in such bad shape that doctors saw no other option than amputating it while he was unconscious. Although Capp was fitted with a prosthetic leg afterwards, his father couldn't afford replacing it each time his son grew bigger. As a result, the boy often walked with a limp. In high school, Capp was put in a class for disadvantaged teens, where there was a lot of bullying. The boy avoided being targeted through his drawing talent, as his fellow pupils asked him to make nude drawings of their female teacher. She was initially supportive of Capp's graphic skills until finding out about her "pornographic" portrayals. The woman was so shocked that she ran out of the classroom screaming, never to be seen again. Capp was determined to become a cartoonist after reading that Bud Fisher earned 4,000 dollars a week drawing his newspaper comic 'Mutt & Jeff'. However, since Capp constantly couldn't pay his tuition, he was forced to drop out of Bridgeport High School and several art schools, including the Boston Museum School of Fine Arts, the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and the Designers Art School in Boston.

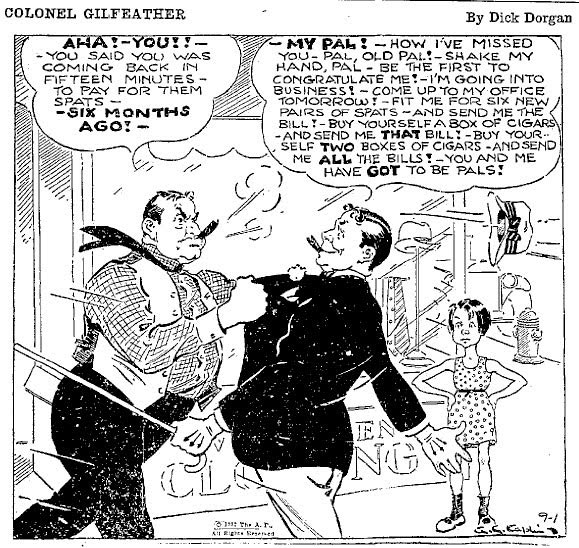

'Colonel Gilfeather'.

Colonel Gilfeather (Mister Gilfeather)

In the spring of 1932, Capp hitchhiked to New York City, where he eventually found a job at Associated Press, taking over Dick Dorgan's comic strip 'Colonel Gilfeather'. However, he hated the series, and eventually tried to give it a new hook by retitling it to 'Mr. Gilfeather' and focusing on the colonel's skirt-chasing younger brother. Still, by August 1932, Capp passed the pencil to Milton Caniff, with whom he already worked together and who remained a lifelong friend.

Joe Palooka and the Capp-Fisher feud

In 1933, Capp became a ghost artist for Ham Fisher's boxing serial 'Joe Palooka' at the McNaught Syndicate. Both cartoonists had different recollections of their collaboration and break-up. According to Fisher, Capp begged him for a job and he took pity on him, despite not really needing an extra assistant at the time. For a while, the young cartoonist lettered and inked Fisher's series. However, when Fisher went on a holiday, Capp demanded a raise, blackmailing Fisher that otherwise he might not continue the strip in his absence. The disgruntled veteran refused, fired Capp and said he took the work with him on his trip. Once he returned back home, Fisher claimed, Al Capp begged to be rehired again. Instead of taking him back, Fisher said he arranged a job for him with the United Feature Syndicate.

Al Capp drew the "Big Leviticus" storyline in Ham Fisher's 'Joe Palooka' comic (19 November 1933).

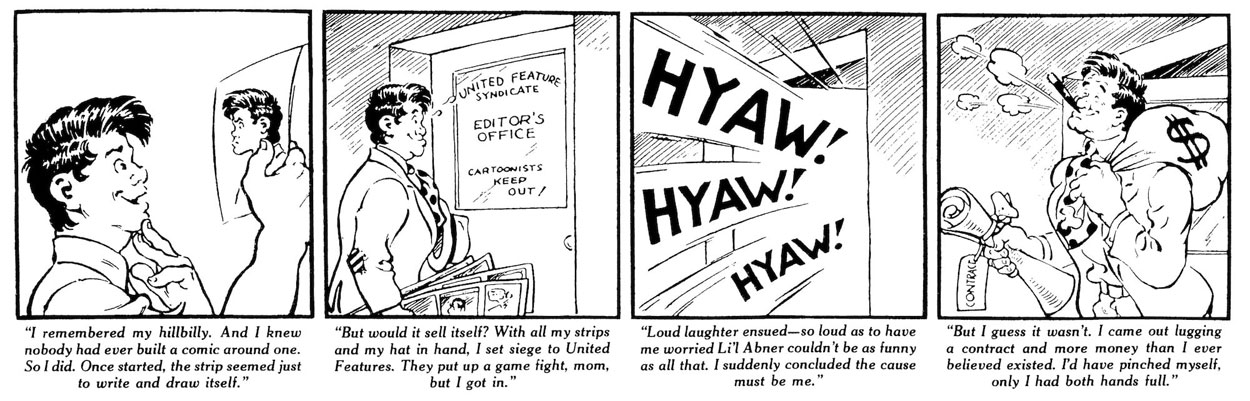

Al Capp had a different recollection. First of all, he was far more than just an inker and letterer. Capp said that he drew all of the Sunday pages in their entirety, enriching the comic with new storylines and characters, for instance the hillbilly Big Leviticus (November 1933). In his opinion, Fisher left him without payment during a six-week vacation, which prompted him to create the concept for 'Li'l Abner' to have another source of income. At first, King Features Syndicate showed interest, but they nevertheless insisted on changing basically everything about his concept. So instead, in June 1934, Capp signed a contract with United Feature, which was less well-paid, but at least kept his concept the way it was. When Fisher found out that Capp had joined another syndicate with a hillbilly strip, he was supposedly so furious that he tried to sue his former assistant. Fisher, however, claimed that the vacation only took "one week" and that he didn't sue Capp, only registered a complaint when Capp took credit for a November 1933 'Joe Palooka' hillbilly narrative starring a character called Big Leviticus, which was supposedly the formula on which the success of 'Li'l Abner' was built. Capp denied this accusation of plagiarism, insisting that he came up with the hillbilly narrative in the first place. Whether Capp had invented the entire Big Leviticus story arc, or Fisher guided him through, has remained unsolved.

1937 promotional comic in which Al Capp explained how he created his hit series.

Capp and Fisher's disagreements evolved into a lifelong bitter feud, with both accusing the other of being a hack. Capp claimed Fisher couldn't draw and 'Joe Palooka' was "the kind of comic I deplore, a glorification of punches and brutishness." In his opinion, Fisher could never understand that he had stronger creative ambitions and, above all, wanted better payment. He satirized Fisher twice. First, as a horse named "Ham's Nose-Bob", in reference to the news that Fisher had his nose remodeled. Secondly, as "Happy Vermin, the world's smartest cartoonist", who takes credit for other people's creations. In October 1948, Fisher accused Capp of hiding "pornographic images" in panels of 'Li'l Abner', submitting them both to the United Feature syndicate and a New York judge, who both dismissed the case after Capp showed them the original artwork. The April 1950 issue of The Atlantic Monthly ran Capp's essay 'I Remember Monster', in which he described a former employer in very harsh terms. Although Fisher wasn't mentioned by name, he instantly recognized himself in the description. In 1954, Fisher tried to prove the subliminal pornography in 'Li'l Abner' again, this time in front of the Federal Communications Commission. When the National Cartoonist Society investigated the matter, the tables were suddenly turned. Fisher was accused of having perpetrated a hoax and faced being banned from the Society. Before this could happen, the disgraced cartoonist committed suicide. Capp expressed no empathy, declaring Fisher taking his own life "his greatest accomplishment" and a "personal victory".

While Fisher's claims that 'Li'l Abner' contained subliminal erotic imagery have always been described as a deliberate, pathetic attempt by Fisher to paint Capp in a bad light, later biographers have questioned these claims. Michael Schumacher and Denis Kitchen investigated the matter in their 2013 biography 'Al Capp: A Life to the Contrary', and felt Fisher's accusation may not have been that far-fetched. Comics biographer R.C. Harvey, who investigated the Capp-Fisher feud independently, was even certain that Capp deliberately snuck in subliminal erotic imagery in 'Li'l Abner' that most readers simply never noticed.

Early 'Li'l Abner' (1936).

Li'l Abner

On 13 August 1934, the first daily episode of Capp's signature comic 'Li'l Abner' appeared in The New York Mirror and eight other U.S. papers. Syndicated by United Feature (nowadays United Media), it was a success from the start. Six months after its debut, on 24 February 1935, a Sunday page was added. The series is set in the American state of Kentucky, in the fictional village of Dogpatch. It initially started off with poking fun at stereotypes associated with the U.S. South. All Dogpatch villagers are simple-minded farmers, barely aware of modern civilization. They talk in Southern slang, peppered with word play and additional neologisms. The Dogpatchers live in log cabins, surrounded by pine trees, mountains and creeks. While not the first "hillbilly comedy" in U.S. media, 'Li'l Abner' can be credited with popularizing the genre on a national and international scale. Capp drew additional inspiration from "tall tales", a type of folkloric stories originating from the region, which put emphasis on unbelievable but entertaining anecdotes. These exaggerated narratives worked perfectly as cartoony comedy.

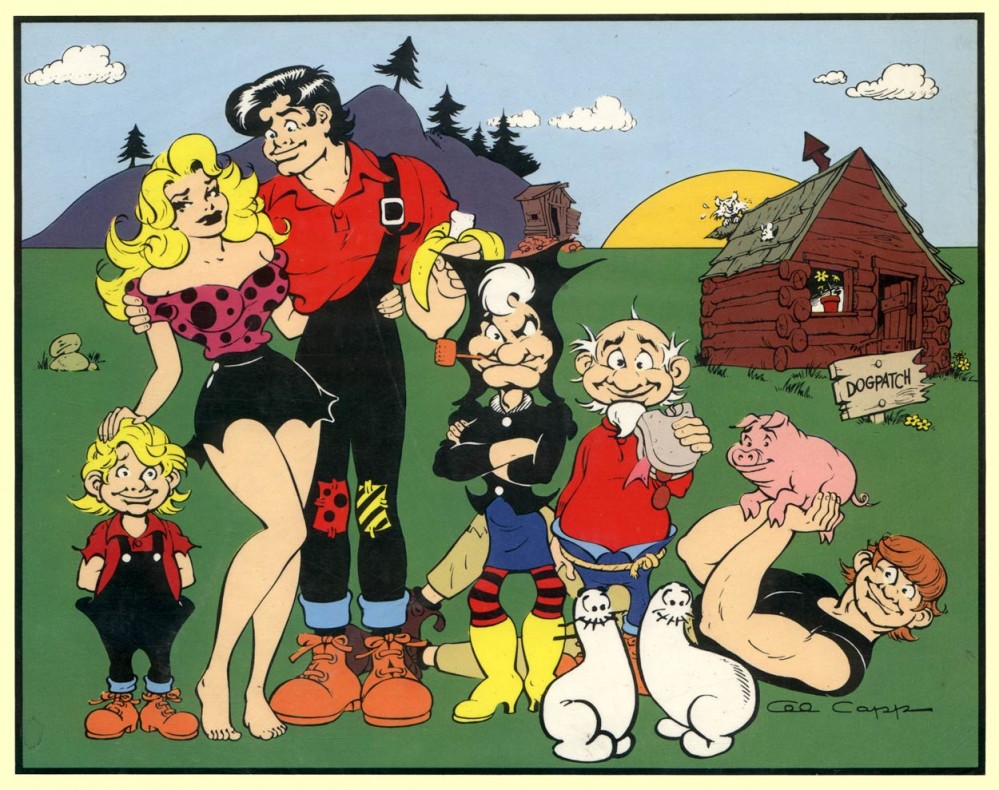

Li'l Abner: characters

The feature's hero, Abner, is a super strong young man. He owes his strength to his mother, Mammy Yokum, who, despite her advanced age, is very feisty. Unfortunately, Abner inherited his intelligence from his feather-brained father Pappy. Abner is often fooled by tricksters and frequently gets himself into trouble. His girlfriend Daisy Mae usually has to help him out. The two seem a good match, but each time Daisy asks Abner to marry her, he runs away. Daisy chasing Abner became the series' most famous running gag. The final member of Abner's family is the pet pig, Salomey.

Capp made Dogpatch a believable, three-dimensional location, complete with an official founder, Jubilation T. Cornpone, a general of the Confederate Army. The town has a factory, Skonk Works, run by Big and Barney Barnsmell, where the toxic fumes are so repellent that they poison anything and anybody in its vicinity. Over the years, the cast was expanded with countless unforgettable characters. One of them was the sleazy preacher Marryin' Sam, who specializes in quick and cheap weddings. For a long while, he tried in vain to make Abner and Daisy Mae tie the knot, until he finally succeeded in 1952. The couple soon had a son, Honest Abe (1953). In September 1954, Abner turned out to have a long-lost brother, "Tiny" Yokum, who, despite his nickname, was actually tall and brawny, but even more stupid than Abner. Abner also has a monosyllabic cousin, Silent Yokum, who only speaks when necessary. Capp often used him to provide cliffhangers at the end of an episode.

Abner and Daisy Mae's wedding in 1952.

Sadie Hawkins is the eternal young bachelorette, whose father eventually organizes a special dating event, Sadie Hawkins Day, that became an annual tradition in the village. Moonbeam McSwine is another single woman, though she owes this due to her lewd and lazy behavior. The gorgeous, raven-haired sex bomb prefers smoking a corncob pipe and lying around in the mud, alongside pigs. Capp based her looks on his own wife, Catherine. Stupefyin' Jones may very well be the best-looking woman of Dogpatch, as she is so sexy that any man who sees her is instantly paralyzed. She is the cousin of Available Jones, a shady businessman who can help anybody with anything, albeit for a hefty sum. At the time, such attractively-drawn female characters were a rare sight in U.S. newspaper comics. During World War II, images of Sadie Hawkins, Moonbeam McSwine and Stupefyin' Jones were painted on real-life U.S. bomber planes, along with drawings of real-life pin-ups like Betty Grable. Capp, however, is also the creator of arguably the ugliest female character in comics: Lena the Hyena. For many episodes, she was deliberately drawn off-screen, because her looks shocked anybody who saw her.

'Li'l Abner' (15 September 1946).

The town of Dogpatch is run by senator Jack S. Phogbound, a corrupt politician who threatens potential hesitant voters with a gun. In the outskirts of the town live two village idiots, Hairless Joe and Lonesome Polecat, who are so primitive that they are close to cavemen. They have a special liquor, Kickapoo Joy Juice, which apparently can be used for everything. Its ingredients are equally mysterious. Several other bizarre people cross Abner's path. Joe Btfsplk has a head constantly hovered over by a raincloud, bringing everyone bad luck. The hermit centenarian Ole Man Mose has the power of prophecy, despite making vague predictions.

The comic's villains are also notable, such as the heartless capitalist General Bashington T. Bullmoose, a man so wealthy that he has a monopoly on almost every product. His catchphrase "What is good for General Bullmoose is good for the country, and vice versa" was based on a real-life quote by Charles E. Wilson, head of General Motors, who in 1952 told a Senate subcommittee: "What is good for the country is good for General Motors, and vice versa." Dogpatch is also terrorized by Wolf Gal, a seductive feral woman, who lures villagers away to give her wolf friends something to eat. Another dangerous female is Nightmare Alice, a voodoo witch who teams up with witch doctor Babaloo (from the Belgian Congo) and her demonic niece Scary Lou. Equally menacing are "the world's dirtiest wrestler" Earthquake McGoon and his identical cousin, Typhoon McGoon. A mysterious person named Evil Eye Fleagle possesses an "evil eye" that can be used as a weapon, but is so powerful that Fleagle himself can barely control it. But none can top The Scraggs family, with whom the Abner family has an ongoing feud. The Scraggs are so evil that they "once set an orphanage on fire just to have light while reading - despite being analphabetics".

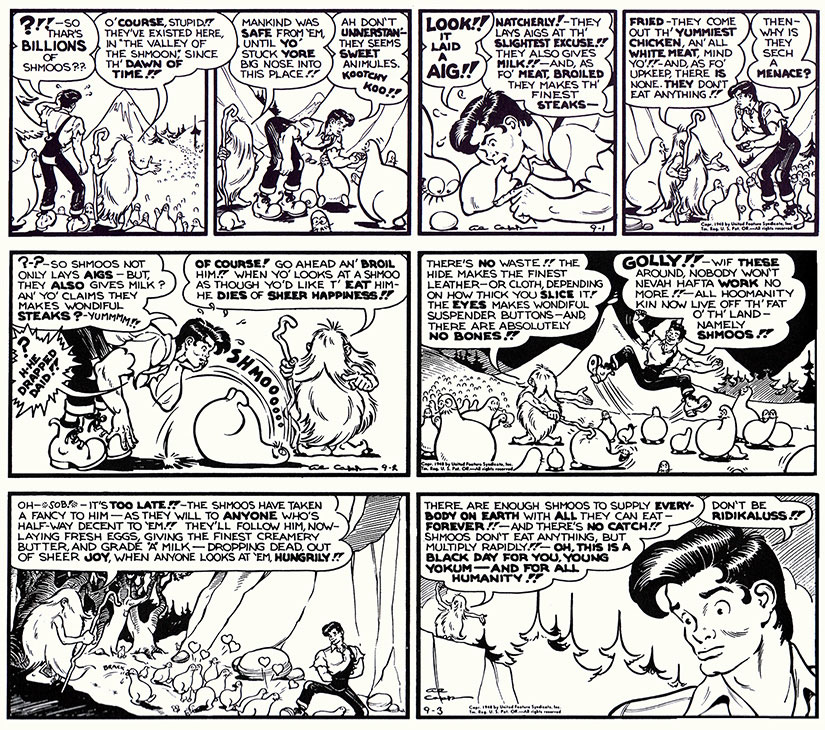

Al Capp's imagination knew no boundaries. He let his characters travel to exotic places with equally odd people and creatures. In April 1946, he introduced Lower Slobbovia, a satire of the Eastern Bloc. This semi-Soviet state was constantly covered in snow and ice. Abner and his friends also encountered the Bald Iggle, whose gaze caused everybody to tell the truth. The most memorable animal featured in the series is the Shmoo, a pear-shaped creature so beneficial to mankind that its kind needs to be wiped out, because they're a threat to business.

'Li'l Abner Sunday of 29 May 1938, with its trademark use of language.

Li'l Abner: language

A staple of the 'Li'l Abner' comic is Al Capp's use of language. All his regular cast members speak with a stereotypical accent associated with the U.S. South, rendered phonetically. To emphasize their primitiveness, Capp lets them make spelling errors and pronounce certain words and expressions incorrectly. "Naturally", for instance, becomes "natcherly", and "I have spoken" turns into "Ah has spoken!". Many of their self-described proverbs and aphorisms are also laughable to readers, like Mammy's "Good is better than evil, becuz it's nicer!" Characters from other parts of the USA and foreign countries are also given stereotypical speech patterns.

Capp was certainly not the first comic artist to use eccentric speech: Rudolph Dirks' 'The Katzenjammer Kids' and George Herriman's 'Krazy Kat' were important predecessors. But he also drew inspiration from the writings of Charles Dickens, Damon Runyon and Mark Twain. Capp's linguistic comedy additionally inspired other comics, like Walt Kelly's 'Pogo', also set in the U.S. South.

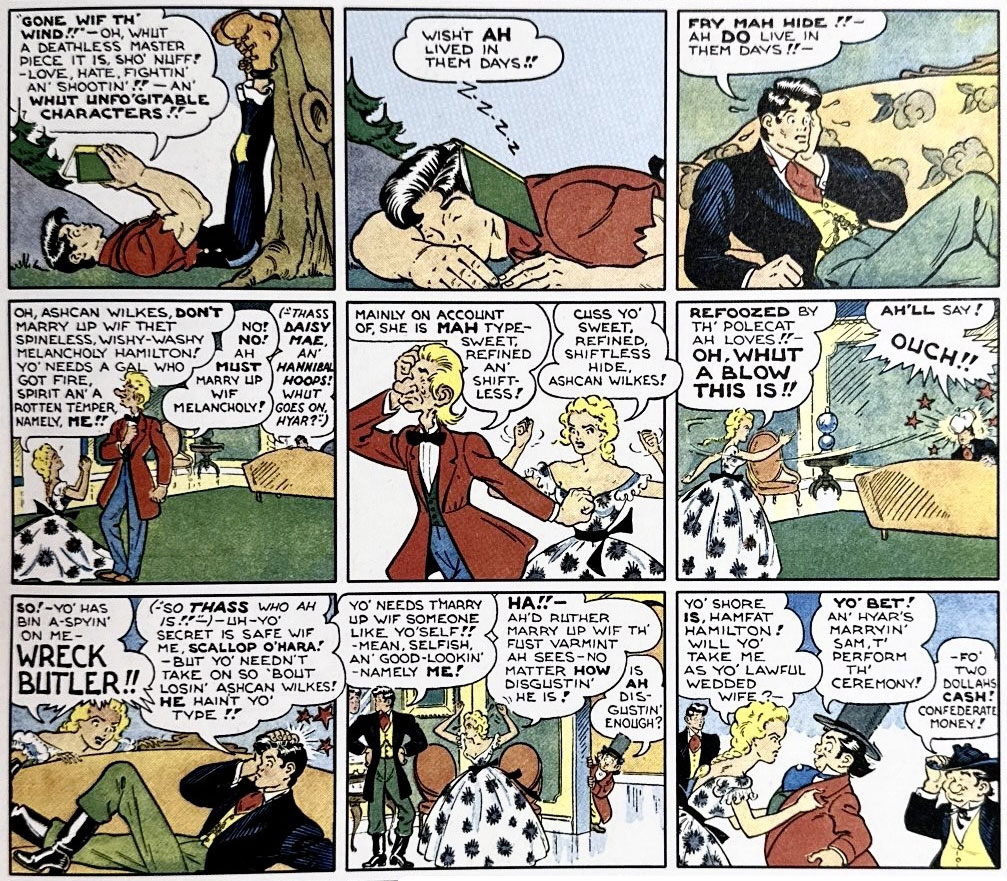

'Gone With The Wind' parody in 'Li'l Abner'.

Li'l Abner: parody and satire

One thing that set 'Li'l Abner' apart from most other comics serialized in the 1930s and 1940s, was its satire. Previous newspaper comics occasionally referenced current events or media stars, but just for a mild, throwaway gag. Capp, on the other hand, had a more sophisticated approach. As early as the late 1930s, some narratives in 'Li'l Abner' were parodies of well-known novels and films, like John Steinbeck's 'The Grapes of Wrath' and Margaret Mitchell's 'Gone With The Wind'. By the early 1940s, 'Li'l Abner' had become an elaborate, all-encompassing satire of politics, economics, advertising, fashion and popular media. Capp gave many real-life celebrities of the day guest roles. Some under their own names, others as thinly disguised parodies, like Gloria Van Wellbuilt (Gloria Vanderbilt) and Rock Hustler (Rock Hudson).

Capp even parodied other comics. In a 1941 plot, he introduced "The Flying Avenger", an obvious mockery of Joe Shuster & Jerry Siegel's Superman. He not only addressed the lack of logic and infantility within the superhero genre, but also the shrewd marketing techniques behind it. Over the years, 'Li'l Abner' featured clever spoofs of Milton Caniff's 'Steve Canyon', Allen Saunders and Dale Conner's 'Mary Worth', Charles M. Schulz' 'Peanuts', Nicholas P. Dallis' and Marvin Bradley's 'Rex Morgan, M.D.', Harold Gray's 'Little Orphan Annie' and Ed Verdier's 'Little Annie Rooney'. Capp's satire was often vicious, mocking, for instance, the melodrama in 'Mary Worth' and the "amateurish" graphic style of 'Peanuts'.

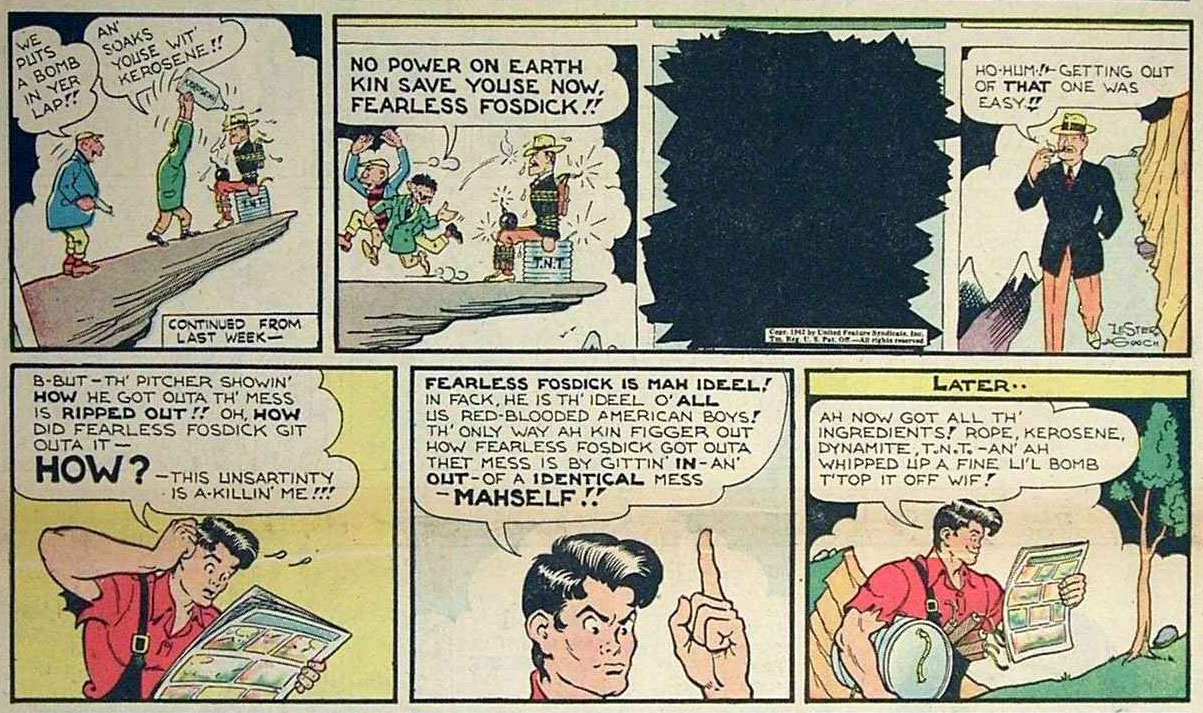

'Fearless Fosdick by Lester Gooch' in the Li'l Abner strip. 19 February 1950.

Capp's most notable parody was introduced on 30 August 1942: 'Fearless Fosdick', a spoof of Chester Gould's comic strip sleuth 'Dick Tracy'. Fearless Fosdick basically looks like Tracy, but with an added moustache. Capp pushed the cartoony villains and gruesome violence in 'Dick Tracy' completely over the top. He also gave 'Fearless Fosdick' a creator: the "famous" cartoonist Lester Gooch, who is depicted as a nervous wreck, constantly writing himself into a corner and then stressing out for being unable to solve his plotline before next week's deadline. 'Fearless Fosdick' quickly became a running gag and the first known example of a "comic within an a comic".

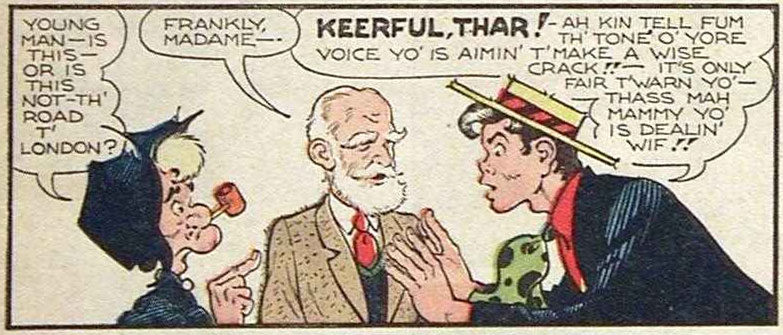

Mammy Yokum and Abner meet George Bernard Shaw, one of the cartoonist's favorite writers.

But Capp went beyond mere spoofing. Several storylines in 'Li'l Abner' are metaphors for real-life political and social issues. He was particularly fascinated with the commercial exploitation of certain trends, especially the hypocrisy behind it and its shallow mass hysteria. The fact that 'Li'l Abner' itself was a merchandising craze and Capp a media celebrity in his own right didn't escape him. In some gags, he poked fun at himself and his creations. Despite reaching millions of readers, Capp didn't play it safe. He dared to tackle racism, the Cold War, Joseph McCarthy's anti-communist witch hunts, the civil rights movement and the hippie subculture in a time when these topics weren't challenged by the majority of people. In 1956, for instance, he introduced a family discriminated against because of their unusual square eye shape. Through Mammy's efforts, they are accepted by the local community.

Much of the later comedy in 'Li'l Abner' revolved more around these multi-layered satirical references than the main cast. Capp attracted more attention from adult readers, particularly intellectuals, who otherwise regarded comics as mindless juvenile pulp. While George Herriman's 'Krazy Kat' was already a beloved intellectuals' darling, during its initial run (1913-1944), its reputation was hampered by the lack of translations outside of the USA. 'Li'l Abner', on the other hand, was translated all across the globe and so gained more widespread acclaim. Famous sociologist Marshall McLuhan praised 'Li'l Abner' in his book 'Understanding Media' as a "paradigm of the human situation".

Li'l Abner ponders about the Fearless Fosdick comic (29 November 1942).

Li'l Abner: metafictional comedy

In his 'Li'l Abner' comic, Al Capp enjoyed breaking the fourth wall, usually through his comic-within-a-comic 'Fearless Fosdick'. On 29 November 1942, for instance, Abner receives the funny pages, but notices a panel is missing in the 'Fearless Fosdick' comic. As a result, he has no clue how his hero managed to save himself from a sticky situation. Soon after, Abner is placed in the exact same life-endangering threat as Fosdick, wishing that he knew how Fosdick "got out of this mess." In the next episode, it turns out Abner was only dreaming. When he eventually obtains an undamaged version of the Fosdick comic he read earlier, he finds out that Fosdick was also saved by the exact same corny "it was all a dream" plot device.

In 1954, Daisy Mae is reading the latest 'Fearless Fosdick' episode and is curious whether Fosdick and his sweetheart Prudence will get engaged in the next episode. Abner dismisses this cliffhanger as "the usual comic strip trick to keep stupid readers excited." The irony continues when Abner proposes to Daisy Mae afterwards and they get married. His prediction about Fosdick turns out to be true: in the next episode, Fosdick and Prudence break off their engagement, restoring the status quo. He and Daisy Mae, on the other hand, stayed married for the rest of the series.

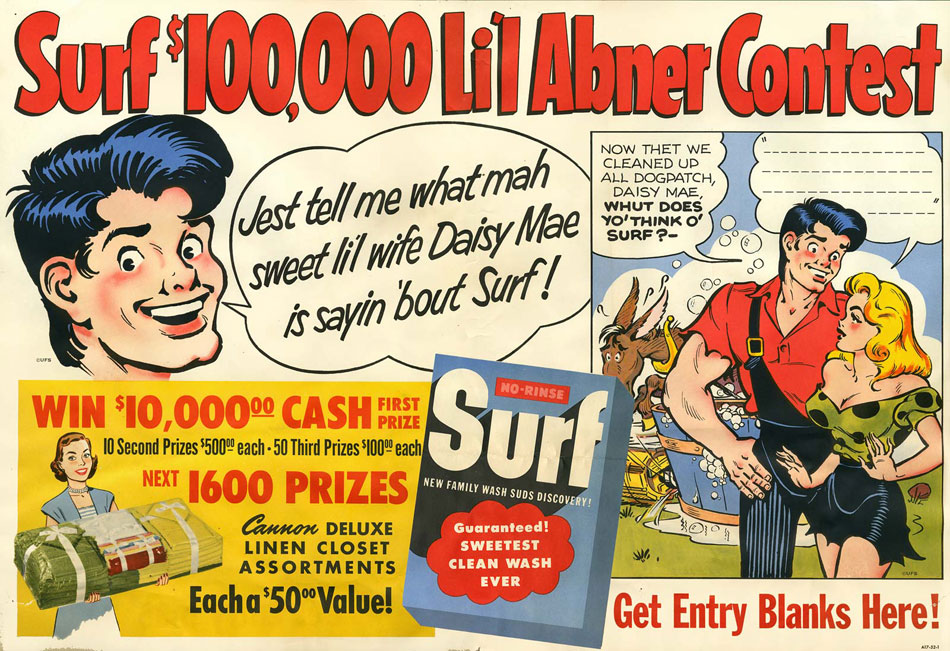

Li'l Abner promoting Surf washing powder.

Li'l Abner: success

'Li'l Abner' managed to reach a wide and versatile audience. Capp's dynamic, appealing artwork, witty comedy and sophisticated contemporary satire proved a golden combination. At the height of its success, the comic ran in over 900 newspapers worldwide. It was translated in several languages, including French (running under different titles in different countries: 'Tibert le Montagnard', 'Abner Le Petit Américain', 'Le Jeune Samson' and 'Le Petit Joson'), Swedish ('Knallhatten') and Portuguese ('Fernando', in Brazil as 'Família Buscapé'). The series gained celebrity fans like Hollywood actors Charlie Chaplin, Orson Welles, Harpo Marx, writers Marshall McLuhan, John Updike, William F. Buckley, film director Russ Meyer, caricaturist Al Hirschfeld, economist John Kenneth Galbraith and British Queen Elizabeth II. Novelist John Steinbeck named Capp "possibly the best writer in the world today" and recommended him for the Nobel Prize in Literature. Both Steinbeck and Chaplin wrote forewords to a 1953 paperback collection of 'Li'l Abner'. Frank Sinatra enjoyed Capp's caricature of him and always sent the cartoonist champagne whenever he saw him in a restaurant. In 1969, Arthur Asa Berger devoted an essay to the series, 'Li'l Abner: A Study in American Satire', making it one of the first U.S. comics to be subject of serious analysis.

Sadie Hawkins Day was first introduced in November 1937, and then returned annually.

Al Capp was a smart businessman, who knew how to keep both his series and himself in the public eye. As early as November 1937, various American high schools and colleges started organizing real-life "Sadie Hawkins Days", in which singles could date one another. Capp was quick to jump on the bandwagon and promoted the event every November in his comic. Capp additionally organized readers' contests and clever cliffhangers to keep people tune in for the next 'Li'l Abner' episode. One of the most famous examples was a 1942 storyline in which the character of Lena Hyena always remained off screen, but scared off other characters for being "the World's Ugliest Woman". As she intrigued readers who wanted to see this invisible character, Capp launched a contest to let readers draw their own creative interpretation of Lena's face. In the next Sunday comic, the winning entry was printed: a drawing by a still unknown Basil Wolverton. Thanks to Capp's media promotion, Wolverton's cartooning career was launched. When Abner and Daisy Mae married in 1952, it was a cover story in Life Magazine. Capp kept readers in additional suspense when Daisy Mae got pregnant, lasting well beyond nine months. The cartoonist recalled that impatient fans started sending him medical books. When the kid was eventually born, Capp kept teasing his audience for an additional six weeks by letting the boy be stuck in a pants-shaped stovepipe, so people couldn't determine whether it was a boy or a girl. Eventually the child turned out to be a boy and was named Honest Abe.

In November 1947, Capp sued his syndicate, United Features, for 14 million dollars to get a better contract deal. He also spoofed them in 'Li'l Abner', through the corrupt newspaper manager Rockwell P. Squeezeblood. A year later, Capp received the rights to his own comics and all financial shares that came along with it. A rare position for most newspaper artists, allowing him to bring more money into his own pocket and expand his creative freedom. He established his own company, Capp Enterprises, with Capp's brother Bence Caplin as its chief operating officer. In 1964, Capp left United Feature and joined the Chicago Tribune New York News Syndicate.

The Shmoos were break-out characters from Al Capp's 'Li'l Abner' comic.

In the 1940s and 1950s, 'Li'l Abner' spawned numerous merchandising items, including hand puppets, dolls and Halloween masks. The characters promoted Fruit of the Loom clothing, Pedigree pencils, Ivory soap, Strunk chainsaws, Head & Shoulders shampoo, General Electric lightbulbs and Grape-Nuts and Cream of Wheat cereal, among many other products. The comic's liquor brand Kickapoo Joy Juice was made into a real-life licensed soft drink, still sold today by the Monarch Beverage Company of Atlanta, Georgia. A veritable cash cow was the character Shmoo, whose cuteness struck a chord with millions of readers. Between 1948 and 1949, the pear-shaped creature was featured on dozens of products, ranging from clothing, wallpaper and cleaning products to toys, jewelry and cutlery. He even inspired a dance craze. During the 1948 U.S. presidential elections, Republican candidate Thomas Dewey even accused sitting president Harry S. Truman of "promising everything, including the Shmoo!". In Louisville, Kentucky, Morton Grove, Illinois, and Seattle, Washington, there were at least three family restaurants based on ‘Li'l Abner'. Between 17 May 1968 and 14 October 1993, there was a 'Li'l Abner' theme park, Dogpatch USA, in Marble Falls, Arkansas.

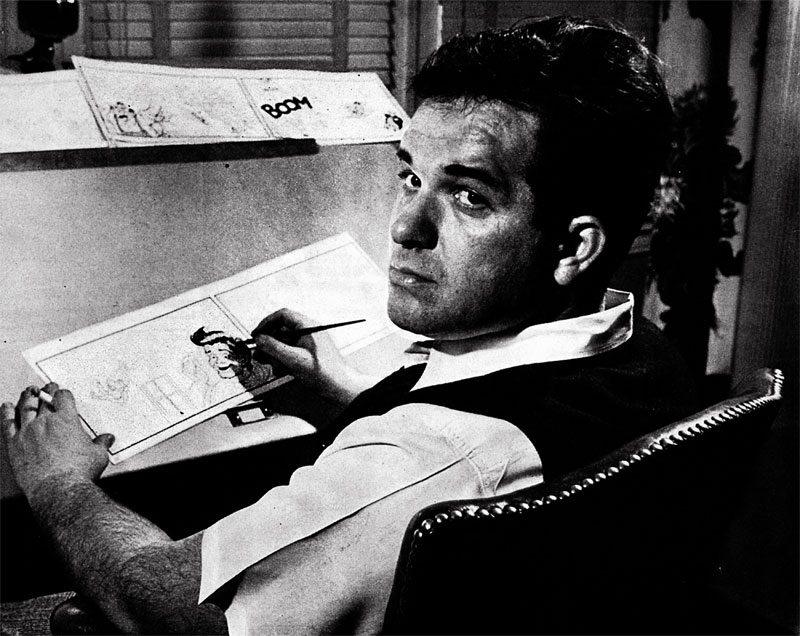

Even the cartoonist Al Capp himself became an unexpected media star. Between the 1940s and 1970s, he wrote his own columns in magazines such as Life, Show, Pageant, The Atlantic, Esquire, Coronet, The Schenectady Gazette (nowadays The Daily Gazette) and The Saturday Evening Post. Together with Lee Falk, he ran the Boston Summer Theatre. Capp appeared in various talk, variety and game shows, most notably as a panel member on the quiz 'Who Said That?'. Capp even hosted several programs of his own, like the talk shows 'The Al Capp Show' (1952), 'Al Capp's America' (1954), 'Do Blondes Have More Fun?' (1967) and 'Al Capp' (1971-1972) and the game show 'Anyone Can Win' (1953). He had a cameo in the film 'That Certain Feeling' (1954) and guest starred in episodes of the TV shows 'Odyssey' ('The Comics', 1957)) and 'Wide Wide World' ('The Sound of Laughter', 1958). Capp also advertised Sheaffer fountain pens, Rheingold Beer (despite being a teetotaler) and Chesterfield cigarettes. Soon he became the most recognizable cartoonist since Walt Disney.

The success of the newspaper comic also led to a comic book series published by Toby Press in the 1950s.

Li'l Abner: media adaptations

NBC produced a 'Li'l Abner' radio serial (1939-1940), which also paved the way for a live-action comedy film, 'Li'l Abner' (1940), directed by Albert S. Rogell, with Buster Keaton as the character Lonesome Polecat. A straightforward "hillbilly comedy" instead of a sharp satire, the picture was no success. The Broadway musical 'Li'l Abner' (1956), with lyrics by Johnny Mercer and music by Gene De Paul, was far better received. The stage play was adapted into another Hollywood film, 'Li'l Abner' (1959), directed by Melvin Frank and with Jerry Lewis in a cameo role as Itchy McRabbit. Contrary to the theatrical musical, the film version received mixed reviews.

In 1944, 'Li'l Abner' was adapted into a short-lived series of animated cartoons, produced by Columbia Pictures. Among the animators were Sid Marcus, Bob Wickersham and Howard Swift. Capp didn't like this version and the cartoons were discontinued after five shorts. However, decades later, the character Lena Hyena was given a cameo role in the Robert Zemeckis and Richard Williams film 'Roger Rabbit' as the man-crazed woman who tries to kiss Eddie Valiant when he searches for Jessica Rabbit in Toontown. While Lena mentions her name during this cameo appearance, the 'Li'l Abner' cartoon series had already fallen into such obscurity that barely any viewers realized she referenced a pre-existing character and wasn't specifically created for the film.

Arguably the oddest media adaptation of 'Li'l Abner' was a short-lived children's TV show based on the comic-within-a-comic 'Fearless Fosdick'. Capp collaborated with puppeteer Mary Chase on the project and even changed Fosdick's physical appearance a bit since he feared it looked too similar to Dick Tracy. Both for the show and in his comic, he gave Fosdick a bowler hat instead of a fedora. The 'Fearless Fosdick' show ran on NBC between 1 June and 2 September 1952, broadcast on Sunday afternoons, but failed to achieve high ratings and was cancelled. Fearless Fosdick was also used to advertise the men's tonic Wildroot Cream-Oil. In 1979, Hanna-Barbera produced 'The New Shmoo', another short-lived animated series based on Capp's comics. The Shmoo also returned in the 'Bedrock Cops' segment of ‘The Flintstone Comedy Show' (1980-1984).

Li'l Abner rip-offs and parodies

As can be expected with a popular comic franchise, 'Li'l Abner' also spawned imitations. Several similar comic series were created that also dealt with hillbilly stereotypes, such as Jess Benton's 'Jasper Jooks' (1948-1949), Frank Frazetta's 'Looie Lazybones', Boody Rogers' 'Babe', Art Gates' 'Gumbo Galahad', Don Dean's 'Pokey Oakey', 'Cranberry Boggs' (1945-1949) and Ray Gotto's 'Ozark Ike' (1945-1953) and 'Cotton Woods' (1955-1958) and Paul Gringle's 'Rural Delivery' (1951). Even the popular TV sitcom 'The Beverly Hillbillies' (1962-1971) borrowed from 'Li'l Abner'. However, most of these rip-offs lacked the imagination and nose for clever social commentary that Al Capp had given his comic.

'Li'l Abner' was also famous enough to be spoofed. As early as the mid-1930s, the strip was subjected to a pornographic parody comic, one of the so-called "Tijuana Bibles". Capp actually read this porn spoof and took it as a compliment, telling his assistants that this was the moment he realized he had made it. In a 20 July 1947 episode of his own comic series 'The Spirit', Will Eisner created a 'Li'l Abner' parody with the name 'Li'l Adam'. Capp himself had suggested this crossover and guaranteed Eisner that he would make a parody of 'The Spirit' in 'Li'l Abner'. Yet for reasons unknown, Capp never kept his part of the deal, which soured Eisner's appreciation for his work forever. In 1956, Capp satirized Allen Saunders and Ken Ernst's soap opera comic 'Mary Worth' as 'Mary Worm'. In return, Saunders portrayed Capp as the alcoholic cartoonist Hal Rapp in 'Mary Worth'. The media depicted this as a feud, but in reality the parodies were made in good fun, as a publicity stunt.

In the satirical magazine Panic, Al Feldstein parodied 'Li'l Abner' as 'Li'l Melvin' (1954). A couple of years later, Harvey Kurtzman and Will Elder made the spoof 'L'l Ab'r' in the first issue of Kurtzman's satirical magazine Trump (January 1957). In 1958, Walt Kelly had his character Barnstable Bear from the 'Pogo' strip create his own comic strip: 'Li'l Orphan Abner', which simultaneously spoofed Harold Gray's 'Little Orphan Annie'. In the Fourth Annual Edition of the Worst from Mad, Wallace Wood created 'Li'l Abneh' (1961), depicting Capp as a ruthless moneygrabber named "Al Capital". In September 1961, Ed Fisher and Elder published yet another parody in issue #8 of Help! magazine, titled 'Dogpatch Revisited', in which the hillbilly community has been changed beyond recognition. The French comic creator Roger Brunel also made a sex parody, published in 'Pastiches 2' (1982).

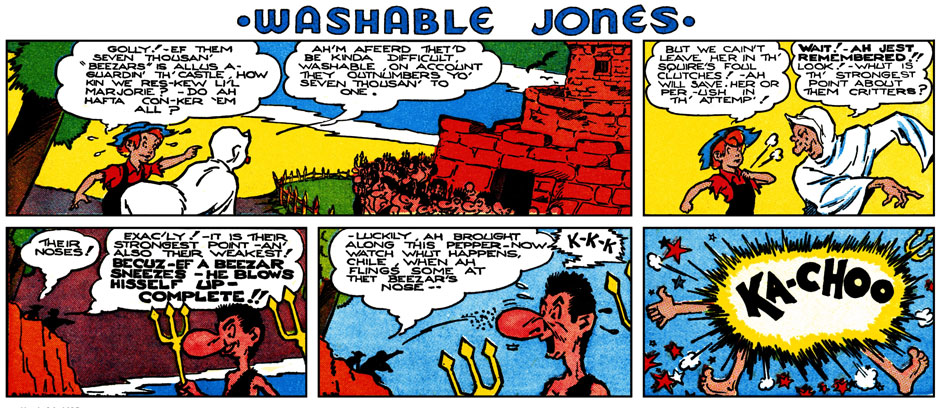

'Washable Jones' topper (24 March 1935).

Li'l Abner: topper comics

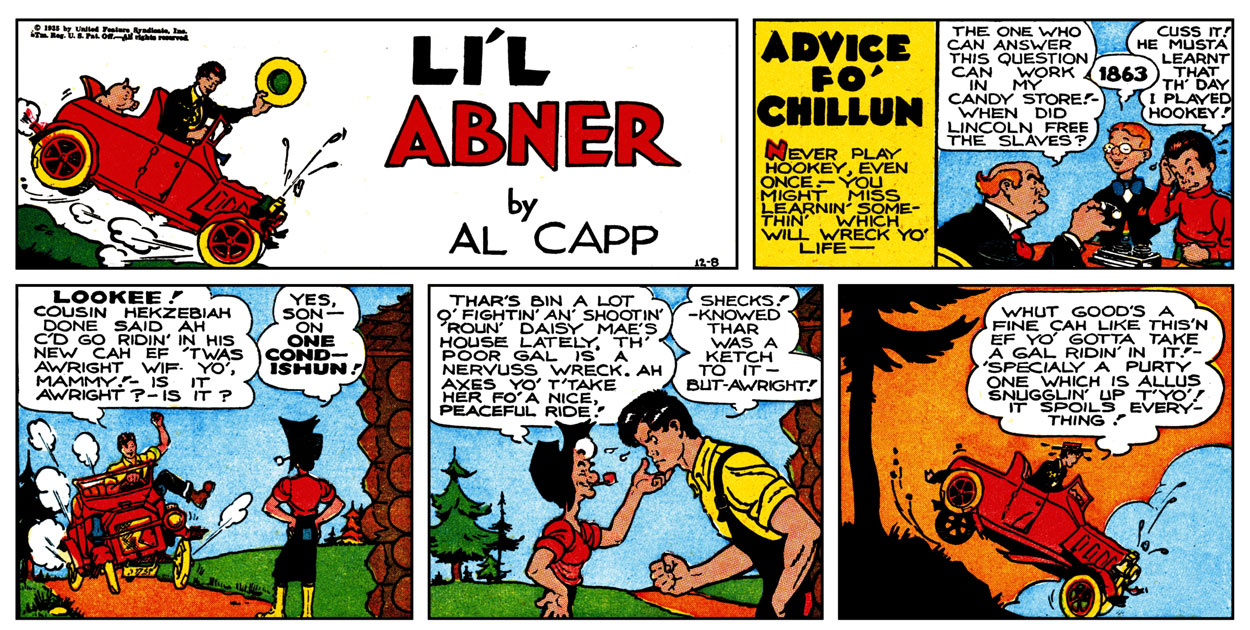

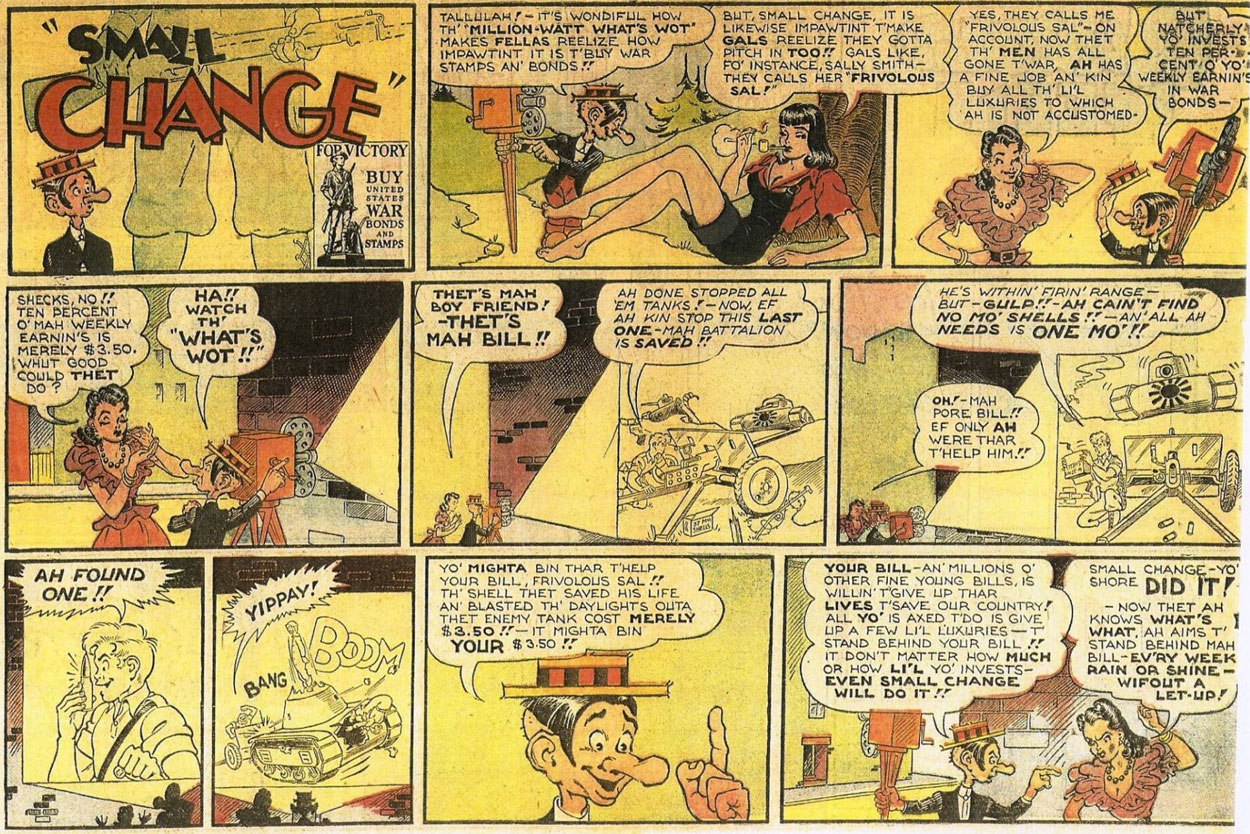

To accompany the Sunday episodes of his hit series, Al Capp developed so-called "topper comics", smaller gag strips appearing along with the weekly 'Li'l Abner' episode. Between 24 February and 9 June 1935, the first one was 'Washable Jones', a simple tale about a young boy who goes fishing and catches a ghost. After a six month-run, it all turned out to be a dream. Capp's second topper comic was the one-panel cartoon series 'Advice fo' Chillun' (23 June 1935-15 August 1943), featuring two-line proverbial wisdoms for children. Readers could send in their own entries, which Capp then visualized in a drawing. The title was sometimes changed to offer advice to "Gals", "Parents", or basically everybody ("Yo' All"). Capp's final topper comic was 'Small Fry', also known as 'Small Change' (31 May 1942-1944). This bi-weekly Sunday comic revolved around a short man, Small Fry/Change, who tries to buy bonds alongside his tall girlfriend Tallulah through a variety of hare-brained schemes.

'Li'l Abner' Sunday comic of 8 December 1935 with 'Advice fo' Chillun' topper.

Abbie an' Slats

While the success of 'Li'l Abner' could have been enough for Al Capp, he decided to launch two extra newspaper comics, scripted by himself, but drawn by other artists. He approached Raeburn Van Buren, a notable illustrator for magazines like Collier's, Esquire and the Saturday Evening Post. But the 46-year old Van Buren initially replied that he felt comfortable enough with his current job and saw no need to become a newspaper cartoonist on the side. Not giving up, Capp convinced Van Buren that story illustration had no long-term future. People would be less willing to read illustrated stories in magazines, since audio plays on the radio provided the same entertainment for free. With a daily newspaper comic, he would at least have a steady income for years. And so, the first episode of Capp and Van Buren's 'Abbie an' Slats' saw print on 12 July 1937, syndicated by United Feature. The daily episodes were tragicomical, comparable to a soap opera. The Sunday pages, launched on 15 January 1939, provided more humorous gags and slapstick.

The main character of 'Abbie an' Slats' was Aubrey Eustace Scrapple, nicknamed "Slats". He is a New York youngster, whose parents have just died. The street-wise orphan decides to leave the city and move to a small rural town, Crabtree Corners, where his older cousin, Abigail Scrapple, lives. Abigail is a spinster, who lives together with her sister Sally. In his new hometown, Slats falls in love with Judy Hagstone, unfortunately the daughter of a cold-hearted businessman, Jasper Hagstone. The man hates Slats because his car once crashed into his limousine. Slats wanted to avoid running over a dog and had no other choice than steer his vehicle away, hereby accidentally crashing Hagstone's prestigious automobile. Later in the series, Slats' heart is won over by another pretty young woman, Becky Groggins, the daughter of eccentric inventor J. Pierpont "Bathless" Groggins. Pierpont soon became ‘Abbie and Slats' breakthrough character. His wacky inventions and adventures across the seven seas drove many plots forward.

Capp kept writing the storylines for 'Abbie an' Slats' until 1945, and then passed this task to his brother, Elliot Caplin. Raeburn Van Buren remained the feature' artist, but was joined in 1947 by an assistant, Andy Sprague. Two later assistants were Don Komarisow and George Shedd. With Caplin as scriptwriter, the series introduced new recurring cast members. Becky received a sister, Sue, while Slats was paired with a best friend/sidekick, Charlie Dobbs. Jasper Hagstone remained Slats' mortal enemy and constantly tried to doublecross him through various schemes. Some episodes were reprinted in Tip Top Comics, a comic book published by United Feature syndicate. In 1971, Van Buren retired, and the final daily episode of 'Abbie ‘n' Slats' was printed on 30 January 1971. The Sunday comic ran until July 1971.

In a funny bit of trivia, columnist Abigail Van Buren (famous for her advice column 'Dear Abby') wrote to Raeburn Van Buren in 1984, that she sometimes received letters that were actually addressed to him. The confusion not only stemmed from their similar last names, but also from the fact that her name ("Abigail") was similar to one of his protagonists, Abigail Scrapple.

'Small Change' topper strip (1942).

Long Sam

On 31 May 1954, a new series scripted by Capp was launched, 'Long Sam'. Drawn by Bob Lubbers, 'Long Sam' was again syndicated by United Feature. Set in the Deep South, Long Sam is a pretty young woman who was raised far away from civilization, making her very uninformed about the outside world. Her mother, "Maw", is a misanthrope who believes all men are obnoxious and dangerous. She shields her daughter away from them, but once the young woman discovers the existence of the opposite sex, she desperately wants to go outside her village. Being sheltered for so long, Long Sam is very naïve and falls in love with every man she meets, while being oblivious to how many other men lust after her. This leads to witty misunderstanding and other shenanigans.

The prime selling point of 'Long Sam' was the gorgeous artwork. Lubbers was an expert in graphically rendering pretty girls, giving the series a sensual undertone. Nevertheless, it couldn't be denied that the comic's main premise was very similar to 'Li'l Abner'. Instead of a naïve male hillbilly living with a feisty mother, 'Long Sam' starred a naïve female hillbilly, living with a mother who looked exactly like Mammy Yokum from 'Li'l Abner'. While in 'Li'l Abner', young women chase after naïve, reluctant males, in 'Long Sam', it's the opposite situation. Capp had actually used a character very similar to Long Sam in his 'Li'l Abner' comic, namely Cynthia Hound-Baskerville (AKA Strange Gal), who lived in an isolated swamp with her overprotective, man-hating mother and became oversaturated with men once she left her home. After a while, Capp passed the scriptwriting of 'Long Sam' to his brother Elliot Caplin. Stuart Hample was also a ghost writer on the series for a while, but by the turn from the 1950s into the 1960s, Lubbers himself took care of the plots. The 'Long Sam' strip was discontinued on 29 December 1962.

Assistants

Throughout his career, Capp took several assistants to help him out with the production of 'Li'l Abner' and his other features. Among his contributing scriptwriters were Stuart Hample, Bob Lubbers and his brother, Elliott Caplin. Inking duties were provided by Andy Amato and Harvey Curtis. Walter Johnson was a notable background artist, and Frank Frazetta also assisted on artwork. Other artists who at one point in their careers assisted on 'Li'l Abner' have been Stan Asch, Tex Blaisdell, Lee Elias, Creig Flessel, Mell Lazarus, Mo Leff, Jack Rickard, Tom Scheuer and George Shedd. Contrary to other cartoonists who hired ghost writers and artists, Capp gave his co-workers equal media attention. He mentioned them in interviews, praised their exact contributions and sometimes allowed them to pose for pictures. However, he always insisted on personally drawing the characters' faces, since he felt their emotional expressions were essential to building readers' investment.

Al Capp featured on the cover of TIme Magazine, 6 November 1950.

Humanitarian work

No matter how successful he became, Al Capp never forgot where he came from. Having experienced poverty firsthand, he often donated money to the needy. This could range from struggling university students to police widows. He made several exclusive 'Li'l Abner' stories for the U.S. Department of Civil Defense, the U.S. Army and the Navy. His characters also adorned campaigns for the U.S. Treasury, the Boy Scouts of America and the March of Dimes. As a man with an artificial leg, Capp was very considerate regarding people with a physical handicap. The generous cartoonist supported the Sister Kenny Foundation, which provided polio research. He also helped out the Cancer Foundation, the National Heart Fund, the Minnesota Tuberculosis and Health Association, the Anti-Defamation League of B'nai B'rith, the National Amputation Foundation and Disabled American Veterans. Capp personally visited hospitals to cheer up and motivate people who had recently undergone an amputation. One such person was Edward M. Kennedy, Jr., son of Ted Kennedy, who, at age 12, was diagnosed with bone cancer in his leg and forced to have the limb amputated. Despite being a Republican and the Kennedys Democrats, Capp still wrote young Edward a letter of public sympathy and emotional support.

A special comic book was made for the Red Cross to encourage thousands of amputee veterans from World War II. Titled 'Al Capp by Li'l Abner' (1946), it was partially an exclusive 'Li'l Abner' story as well as an autobiographical comic, chronicling how Capp, despite his handicap, managed to have a successful career.

In a time when discrimination was more institutionalized than today, Capp supported civil rights for African-Americans and homosexuals. In December 1949, he briefly resigned from the National Cartoonists Society to protest their ban on female members, like 'Teena' creator Hilda Terry. Capp also made his case during the meetings and in a newsletter. Thanks to his status and influence, Capp made Terry the first woman to become a member of the National Cartoonists Society (1950).

'Li'l Abner' (26 November 1949).

Controversy

As beloved as 'Li'l Abner' was, its satire didn't always please its readers. In September 1947, the series was pulled from papers by Scripps-Howard, the syndicate that owned United Feature, over a storyline mocking the U.S. Senate. Edward Leech, head of Scripps, commented that portraying the Senate "as an assemblage of freaks and crooks… boobs and undesirables" wasn't "good editing or sound citizenship." Interestingly enough, Capp once seriously considered running for a seat in the Senate of Massachusetts. Also polarizing audiences was the famous storyline about the Shmoos, innocent creatures targeted by the "crommunist" government of Lower Slobbovia and exterminated by tycoon J. Roaringham Fatback for being "bad for business". Left-wing people interpreted it as mocking socialism and communism, while right-wingers felt Capp lampooned capitalism. In the 10 October 1948 broadcast of 'The Author Meets the Critics', Capp had a live radio debate with psychiatrist Dr. Fredric Wertham. The latter went so far as to link the Shmoo to Nazi war criminal Ilse Koch. Nearly a decade later, between 21 July and 14 August 1955, 'Li'l Abner' featured a storyline in which a caricature of Wertham made a cameo.

In 1949, the editors of The Seattle Times dropped an episode of 'Li'l Abner' because of a storyline in which Abner thinks he's eaten one of his parents, considering this cannibalism joke to be in (pun not intended) "bad taste". In the 1950s, when Capp satirized senator Joseph McCarthy, the FBI kept a file about this "suspicious cartoonist". In 1954, Capp asked showbiz pianist Liberace for permission to caricature him as "Liverachy". Liberace threatened to sue, so Capp changed the character's name in "Loverboynik". This offended the closeted homosexual entertainer even more. In 1966, Capp portrayed protest singer Joan Baez as a whiny, Communist poseur named "Joanie Phoanie", who expresses sympathy for "the common people", but is extremely wealthy herself, charging poor orphans with expensive concert tickets. Baez actually threatened to sue to force a public retraction of the episode. Years later, in her autobiography 'And A Voice to Sing With' (1987), she included the comic strip, adding the commentary: "I wish I could have laughed at this at the time."

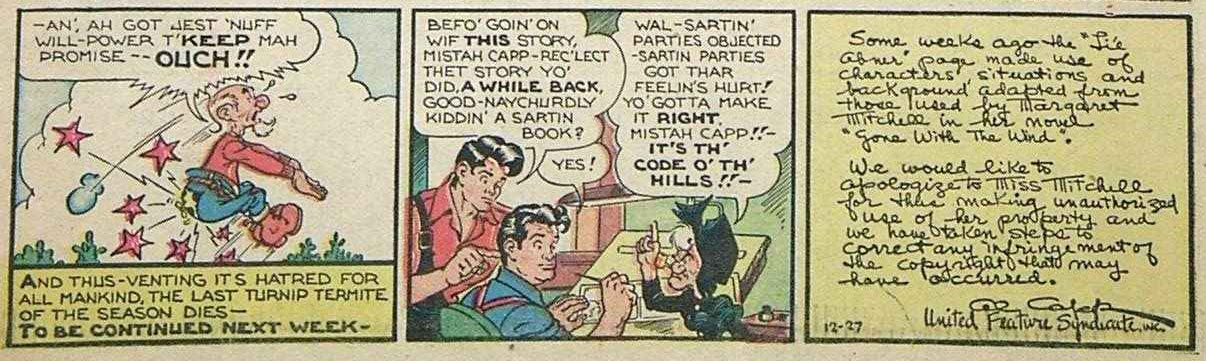

Al Capp's apology for his 'Gone With The Wind' parody (26 December 1942).

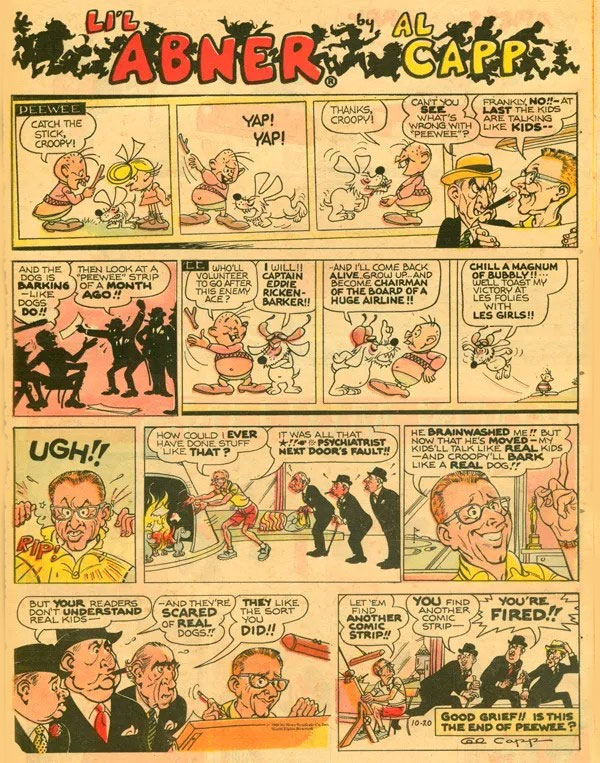

Only twice did Capp actually apologize for a satirical mockery. After parodying 'Gone With the Wind', the author of the original novel, Margaret Mitchell, was so angry that Capp was forced to publish an apology within the 'Li'l Abner' episode of 26 December 1942. Two-and-a-half decades later, in October 1968, he targeted Charles M. Schulz' 'Peanuts' strip. Capp depicted a comic artist, Bedly Damp, whose series 'Pee Wee' stars a group of children talking like adults and a dog who dreams of being a flying ace. 'Pee Wee' is a hit with intellectuals and merchandisers, but loses its popularity once the psychiatrist who lived next door to the comic artist moves away, leaving Damp without a man whose profound musings he can simply transcribe to paper. The syndicate therefore fires Damp, hires the psychiatrist and employs Abner, since they need somebody who "can't draw". The storyline was abruptly discontinued after Schulz wrote Capp a letter of complaint. On 17 October 1968, the matter was even made public by journalist Jack Smith in The Los Angeles Times. Schulz: "I told Capp I was flattered by the attention, but I didn't think it was very funny. I don't think it was very clever. I don't mind parody if it's clever. I thought it was rather dull and heavyhanded. If the truth were known, he probably couldn't get anything funny out of it and went on to something else." Capp reacted: "It's blasphemy, isn't it? I guess there really are some subjects that one doesn't laugh about."

Al Capp's spoof of Charles Schulz's 'Peanuts' comic (1968). The real-life Schulz wrote Capp a letter of complaint, asking him to discontinue it.

By the mid-1960s, 'Li'l Abner' also grew increasingly unpopular with younger audiences. Capp was a vocal supporter of the U.S. Republican Party and convinced that the Vietnam War was a noble cause. He looked down on rock musicians, protest singers, hippies and civil rights activists. As progressive as some of his viewpoints towards minorities were, he once denied a request from Martin Luther King in rather harsh and unfair terms. In 1964, King asked Capp by letter for funds to protect black people from white violence in the American South. Since Capp's studio had helped out the civil rights movement in the past by producing the comic 'Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story' (1957, by Alfred Hassler, Benton Resnik and Sy Barry), King expected a positive reply. Yet Capp wrote back: "(...) When organizations like yours, and leaders like yourself recognize the fact that violence, discrimination and terror are practiced by black Americans against white Americans and bend at least some of your efforts to cleaning up your own mess - people like Governor Wallace will not get such support, and people like me will not feel disenchanted." In 1964, novelist Isaac Asimov also felt Capp was too dismissive of the civil rights movement in 'Li'l Abner', which he expressed in an open letter in the Boston Globe.

In 1969, when John Lennon and Yoko Ono held one of their famous "Bed-In" peace protests in Montréal, Capp visited them. He called them out for their "naïve and phony" peace activism and their nude appearance on the album cover of 'Two Virgins' (1968). Video footage of their heated discussion can be seen in the documentary 'Imagine: John Lennon' (1988). In a 1970 TV special of TV Guide, Capp described student rioters as "unbathed, unshorn and unfragrant", while joking about the counterculture movie 'Easy Rider' (in which the biker protagonists are murdered in the end): "Thank heavens it had a happy ending." A large part of his grudge seemed to stem from his personal hardships. Since he, a poor kid and amputee, had been able to climb to the top, he felt today's generations could do the same, if they weren't so spoiled, privileged and pampered. As he expressed it: "Anyone who can walk to the welfare office can walk to work." (Note the emphasis on "walking", again underlining a certain personal bitterness about his own handicap.)

Capp expressed his old-fashioned opinions not only in interviews and during public appearances, but they also seeped through in 'Li'l Abner'. A typical example is the student group S.W.I.N.E., a group of angry youngsters whom many people in Dogpatch find obnoxious. Their name stand for "Students Wildly Indignant About Nearly Everything." Jokes like these alienated potential new readers, but also longtime fans, even readers who shared his opinions. Too many 1960s-1970s episodes of ‘Li'l Abner' became frustrated attacks at whatever irked Capp about "today's youth". Several of his assistants also got tired of his preachiness. They either quit, or got fired, forcing Capp to rely on less skilled artists instead, further damaging his comic's reputation.

What wrecked Al Capp's public image the most was a huge sex scandal. He had several extramarital affairs, including one in 1940 and 1941 with the young Californian singer Nina Luce. He was frequently accused of sexual harassment and even indecent exposure. In 1968, he tried to seduce a group of female students at the University of Alabama. When the university board was informed about the matter, they asked the cartoonist to leave the building. In preparation of another lecture, this time at the University of Wisconsin in April 1971, Capp had invited a married student, Eau Claire, to a motel room for a "political discussion". Claire was shocked when Capp made suggestive comments, exposed himself and attempted to force her into giving him oral sex. Another female victim at the same university, Patricia Harry, later sued him for rape. More charges at other colleges followed and were made public on 22 April 1971 by journalist Jack Anderson. On 8 May of that same year, the famous comic artist was officially charged with a warrant. Capp "defended" himself in an interview for The New York Times: "The allegations are entirely untrue. I have been warned for some time now that the revolutionary left would try to stop me by any means from speaking out on campuses. My home has been vandalized and I have been physically threatened. This is also part of their campaign to stop me. Those who have faith in me know that I will not be stopped." On 12 February 1972, the trial ended in a 500 dollar fine, plus costs in morals, albeit only for the charge of "attempted adultery" as part of a plea bargain.

Soon Capp was no longer invited for media appearances and several papers dropped 'Li'l Abner' from publication. Recorded conversations from within the White House show that even president Richard Nixon worried the scandal might stain his own administration, since Capp was such an outspoken Republican. In a January 1985 interview, published in Hugh Hefner's Playboy magazine, Hollywood actress Goldie Hawn claimed that when she was 19, Capp tried to sexually harrass her during a casting interview. When she refused his advances, he got angry, "predicted" that she would "never have a career and be better off marrying a Jewish dentist." Later Hawn became a movie star, prompting her to write him a letter about the matter, but never received a reply. On 11 May 2017, she revealed more details about her encounter with Capp, receiving more media attention on the wave of the #MeToo revelations about sexual harassment by media celebrities. In James Spada's 1987 biography about Grace Kelly, he also quotes Kelly's manager, who said that Capp tried to rape Kelly.

Recognition

Al Capp won the 1947 Billy DeBeck Memorial Award (nowadays Reuben Award) and a 1978 Inkpot Award. He posthumously received the Elzie Segar Award (1979) and was in 2004 inducted in the Will Eisner Hall of Fame. In 1995, to celebrate the 100th anniversary of U.S. comics, 'Li'l Abner' was selected as one of 20 classic U.S. comics to receive a commemorative stamp in the 'Comic Strip Classics' series.

Final years and death

On 5 November 1977, the daily episodes of 'Li'l Abner' came to a close, followed by the final Sunday comic on 13 November. In a farewell text, Capp explained that his heart was no longer in it and apologized for the decline in quality, which he blamed on ill health. A few weeks later, more tragedy struck when one of his daughters and his granddaughter died. Capp grew more reclusive and died in 1979 from emphysema. According to biographers Michael Schumacher and Denis Kitchen, a few years earlier the comic legend had one of his assistants destroy entire contents of a storage unit, because some of it contained "incriminating material".

Legacy and influence

The cultural impact of 'Li'l Abner' is still felt today. Various neologisms derived from the series are nowadays part of the English language. A combination of two opposite forces is named a "double whammy". A socially backward or primitive country is named "Lower Slobbovia". In electrical engineering, a certain type of plot has been named a "Shmoo plot", while in particle physics a type of cosmic ray has also been given the name "Shmoo". In both instances because of the similar shape. In socioeconomics, a "shmoo" is a material good that reproduces itself and is captured and bred as an economic activity. The moonshine factory Skonk Works in the comic inspired the nickname of an aircraft organization owned by Lockheed Martin, which in itself became a synonym ("skunk works") for an independent organization working on advanced or secret projects. Capp also popularized a few dialect expressions, often mistakenly believed to have been invented by him, such as "hogwash" ("nonsense"), "natcherly" (a bastardization of "naturally"), "irregardless" (a contraction of "irrespective" and "regardless") "druthers" ("a preference") and the affix "-nik" behind certain nouns.

The first codebreaking computer used by the National Security Agency was named "ABNER". In 1965, a soft drink brand inspired by the series, Kickapoo Joy Juice, was launched and is still in production today. Capp even took credit for the invention of the mini skirt, which his character Daisy Mae already wore in 1934, three decades before it became an actual fashion trend. Jazz musician Turk Murphy named his San Francisco jazz club "Earthquake McGoon's", after the similar villain from ‘Li'l Abner'. The baseball team Sioux City Soos used the character of Lonesome Polecat as their official mascot.

That being said, Capp's comic strip itself has basically vanished from modern-day popular culture. In overviews of the greatest, most influential and artistic comics of all time, 'Li'l Abner' is nowadays often overlooked, or even forgotten. Given what a global cultural phenomenon it once was, this is quite perplexing. The fall from grace can be attributed to many factors. 'Li'l Abner' has never been reprinted in the papers, since so many of its satirical references are nowadays dated. For a long while, there were few complete book compilations available either. People who were only introduced to 'Li'l Abner' during its later, lesser period, therefore only knew it as a shadow of its former self: a comic out of touch with changing times, with its witty satire replaced by tedious, conservative rants. Capp's sex scandals and the resulting court case also tainted his reputation. It overshadowed the merits of his comics and made fans almost embarrassed to admit they admire(d) his work. Several of his former colleagues and assistants also distanced themselves from Capp.

In 1989, a revival of 'Li'l Abner' was considered, with Steve Stiles as the new artist. Capp's widow and brother approved, but his daughter didn't, causing the project to be axed at the last minute. The same year, Kitchen Sink Press made an attempt to republish the entire 55 year-running series chronologically, but when the company went bankrupt in 1999, the project was stranded. In 2010, IDW had another stab at the mammoth task, but the project seems to have stalled out after the ninth volume in 2017.

Still, as time goes by, 'Li'l Abner' has received renewed positive attention. On 15 May 2010, Capp's birth town of Amesbury, Massachusetts, devoted a mural painting to 'Li'l Abner' and renamed the local amphitheater after the cartoonist. To this day, many U.S. high schools and universities still organize annual "Sadie Hawkins Days", where young women can ask out young men for a date. The events are combined with large festivities. Even Capp himself is seen more as a deeply flawed man who had many contradictions about him.

In the United States, 'Li'l Abner' had a strong influence on many satirical comics, including Walt Kelly's 'Pogo', Charles M. Schulz' 'Peanuts', Harvey Kurtzman and Will Elder's parodies in Mad Magazine and Garry Trudeau's 'Doonesbury'. Kurtzman modelled many of his parodies of other media in Mad on Capp's comic spoofs in 'Li'l Abner', while simultaneously using Capp's ambitious approach to satirize everything in modern-day society, from politics, film, radio, TV, advertising and trends, exposing the hypocrisy and marketing lies behind it. Other U.S. artists inspired by Al Capp have been Scott Adams, Gus Arriola, Ralph Bakshi, Jess Benton, Ray Billingsley, Jack Cassady, Frank Cho, Daniel Clowes, Dan Collins, Will Eisner, Jules Feiffer, Mike Fontanelli, Frank Frazetta, Matt Groening, Stuart Hample, Al Hirschfeld, Denis Kitchen, Harvey Kurtzman, Mell Lazarus, Bobby London, Joe Matt, Bill Plympton, Richard Sala, Jim Scancarelli, Charles M. Schulz, Gilbert Shelton, Shel Silverstein, Mort Walker and Skip Williamson. In 1963, Mell Lazarus published his comic novel 'The Boss Is Crazy, Too' (Dial, 1963), about his apprentice years with Capp. When Jules Feiffer wrote a screenplay for the film 'Je Veux Rentrer à la Maison' ('I Want to Go Home', 1989), he included a scene in which a retired cartoonist makes a heart-felt plea for ‘Li'l Abner'.

In Gilbert Shelton's 'The Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers', the brothers read a comic-within-a-comic, 'Tricky Prickears', which, just like 'Fearless Fosdick' in 'Li'l Abner', is a spoof of Chester Gould's 'Dick Tracy'. Matt Groening's animated TV show 'The Simpsons' also has some parallels with 'Li'l Abner', like using a simpleton family framed within an all-encompassing satire of various aspects of modern-day society. While Al Capp once stated that Abner's hometown of Dogpatch was located in Kentucky, he later kept the home state a mystery, much like it has been a running gag in 'The Simpsons' to never reveal in which U.S. state the yellow-skinned family's hometown of Springfield is located. Just like Dogpatch, Springfield also harbors a diabolical businessman (Mr. Burns), corrupt politician (Mayor Quimby), city founder (Jebediah Springfield), hillbilly family (Cletus and his relatives) and a cartoon-within-a-cartoon satirizing media violence ('Itchy & Scratchy').

In Canada, Capp was an influence on John Kricfalusi. In Europe, Capp also had a strong impact: in the United Kingdom, he influenced Roger Law, while in France, he could count Jean David and Albert Uderzo among his followers. Early in his career, Uderzo even signed his work with "Al Uderzo", as a tribute to Capp. The influence of 'Li'l Abner' is very noticeable in Uderzo's own signature comic 'Astérix', from the brawny, feather-brained strongmen (like Obélix) to the multilayered satire. In the Netherlands, Capp inspired Evert Geradts and Marten Toonder, and in Belgium François Craenhals, Gérald Forton and Marc Sleen were admirers. Like Capp, Toonder also mixed satire and eccentric language in his signature series 'Tom Poes'. Sleen imitated political satire and celebrity caricatures in his comic strip 'Nero'. He borrowed the idea of a creature laying money instead of eggs from The Money Ha-Ha in 'Li'l Abner' for the 'Nero' story 'Het Ei van October', while the country of Slobbovia was also used for the nation Slobovia in 'De Pijpeplakkers'. A New Zealand fan of Capp was John Kent.

Secondary literature

For those interested in the life and career of Al Capp, the biographies 'Enigma of Al Capp' (Fantagraphics, 1999) by Alexander Theroux and Michael Schumacher and Denis Kitchen's 'Al Capp: A Life to the Contrary' (LLC Kitchen, Lind & Associates, 2013) are must-reads.