Ralph Bakshi is an American independent animated film producer, best-known as the first to create animated features exclusively meant for mature audiences. Comic fans know him best for his 1972 film adaptation of Robert Crumb's underground strip 'Fritz the Cat'. Tolkien fans know him as the director who made the first (unfinished) attempt to adapt 'Lord of the Rings' (1978) to the big screen. Much like underground comix proved that comics could be more than just innocent children's entertainment, Bakshi did the same for animation. He chose for a gritty, unpolished, personal style, away from the Disney esthetic. Some pictures are set in bleak city life ('Fritz the Cat', 'Heavy Traffic', 'Coonskin'), others are epic fantasy sagas ('Lord of the Rings', 'Wizards', 'Fire and Ice'). He broke several taboos by depicting sex, drugs, graphic violence, swearing and politics in animated films. Bakshi often had to combat censors, executive producers and moral guardians. His pictures additionally had to overcome budget restrictions and other problems. His oeuvre has always polarized audiences, but Bakshi is recognized as a groundbreaking innovator. He paved the way for all independent adult animation in cinema, TV and on the Internet today. His TV animation studio, Bakshi Productions, produced 'Mighty Mouse Adventures' (1987-1988), based on Paul Terry's classic character Mighty Mouse. While he had little to do with their creative process, other than guarding his employees from executive meddling, 'Mighty Mouse Adventures' was a platform for many people who'd breathe fresh air in TV animation. Early in his career, Bakshi also drew a few comic series ( 'Dum and Dee', 'Bonefoot and Fudge' and 'Junktown'), which faded into obscurity until the publication of a 2008 biographical book.

Early life

Ralph Bakshi was born in 1938 in Haifa, Palestine (nowadays Israel), into a Jewish family who emigrated to New York City a year later. He grew up in the seedy heart of Brownsville, a neighborhood in eastern Brooklyn, where poverty, crime, prostitution and racism were an everyday thing. In 1947, his family moved to Foggy Bottom, Washington D.C., where he was a white boy in a black neighborhood and even the single white child in an all-black school. Back then, the U.S. was still racially segregated, so Bakshi's mother had to obtain special permission. In the end, the police still forcibly removed Bakshi from the school. The family moved back to Brownsville, but Bakshi always kept in contact with black people, feeling a connection as an outsider in a hostile society.

As a child, he cut out comic book characters from papers and books and played with them. His graphic influences were Chaim Soutine, Arthur Rackham, N.C. Wyeth, Jackson Pollock, Francis Bacon, George Herriman, Al Capp, Harvey Kurtzman, Bill Mauldin and naturally underground comix artists like Robert Crumb, Gilbert Shelton and Vaughn Bodé. He took many lessons from reading Gene Byrnes' book 'The Complete Guide to Cartooning' (1950). When he took the book from his local library with the intention to borrow it, he noticed a window leading to the street on the side. Changing his mind, Bakshi threw the book outside, so he could secretly pick it up when he went home and keep it. Bakshi admitted that he basically stole it, because he was never going to bring the copy back anyway and desperately wanted to avoid paying library fines, since he couldn't afford them. The book has remained in his possession ever since. In the field of animation, Bakshi was influenced more by the Max and Dave Fleischer cartoons and Looney Tunes shorts of Bob Clampett, Tex Avery, Friz Freleng and Chuck Jones, because Disney films didn't play much in his neighborhood. As a teenager, he also devoured literature about sleazy street life, written by Charles Bukowski and Hubert Selby, Jr.

As a pupil at Thomas Jefferson High School, Bakshi's drawing talent was encouraged by his guidance counselor. She put him in art courses, to avoid him becoming a street hoodlum. The friendly woman even helped him get accepted at the High School of Industrial Arts in Manhattan (nowadays the High School of Art and Design). At this school, he was mentored by African-American veteran cartoonist Charles Allen (1921-1999) and graduated in 1956.

Terrytoons

Bakshi began his animation career at age 18 as a cel washer with the Terrytoons animation studio in New Rochelle. There he worked on such TV series like 'Deputy Dawg' (1960-1961) and learned from veterans like Gene Deitch, Jim Tyer and Connie Rasinski. One of his fellow animators on 'Deputy Dawg' was David Tendlar. During this era, Doug Crane also worked for Terrytoons. Bakshi also collaborated with Al Capp on an animated adaptation of his comic-within-a-comic 'Fearless Fosdick'. While Terrytoons had a reputation for its factory mentality, putting quantity over quality, there was a relaxed atmosphere. His colleagues taught him the value of drawing for fun. Perfection wasn't as important as the heart of what you were doing. Bakshi moved up the ladder from cel washer to inker. One day, he heard that the studio was in desperate need for extra animators, but they only promoted some of his colleagues who'd already worked there for years. Since Bakshi was still considered a rookie, he would've to wait. In a decisive mood, he simply took his desk from the inking department, brought it to the animation floor and started animating. He refused to go back and told his superiors that they needed animators. Since he was willing to do the job, they could either keep him or fire him. Rasinski defended him, whereupon Bakshi, against procedure, was allowed to stay. To avoid trouble with the unions, all the other animation-assistants were also promoted. And so, Bakshi was now the hero of the studio, since many of his colleagues were now given a better (paid) job, while his superiors had the extra crew they desperately needed!

Bakshi impressed many people with his enthusiasm and perseverance. One day, he had made drawings for an animated short, 'Silly Sidney', but unwisely left it all on top of his wastebasket. The next day, the cleaning staff had thrown everything away. Bakshi learned that the garbage would be sent to a paper mill in Philadelphia, to be recycled. He instantly took a train to the mill, but as he entered the building, shouting and screaming, they were already dumping everything. Bakshi managed to find one extreme of his film, realized it was hopeless to go through every piece of paper and returned to Terrytoons. His boss was furious, but he was again allowed to stay. In hindsight, Bakshi credits the fact that he was able to find one of his drawings with "saving his job".

Comics

After hours, Bakshi created comic strips as an outlet to his personal problems. Some of these secret drawings were purely meant to vent frustrations and so he kept them hidden. 'Dum Dum and Dee Dee' reflected troubles between him and his wife. 'Bonefoot and Fudge' featured the mishaps of a wolf and a mouse, while 'Junktown' had anthropomorphic rocks, garbage cans, mailboxes and other street junk interacting with one another. Both centered around people who spent too much time squibbling over trivial matters, a frustration he often felt when dealing with studio heads and executives. He tried to get 'Junktown' published in The Post, but the publisher didn't understand it. In 1988, he also tried to produce it into an animated TV series, but only got as far as a pilot, 'Christmas in Tattertown', which became the first original animated special airing on the channel Nickelodeon. According to Toonopedia, Bakshi may have drawn a comic strip adaptation of Gene Deitch's animated character 'Tom Terrific' too.

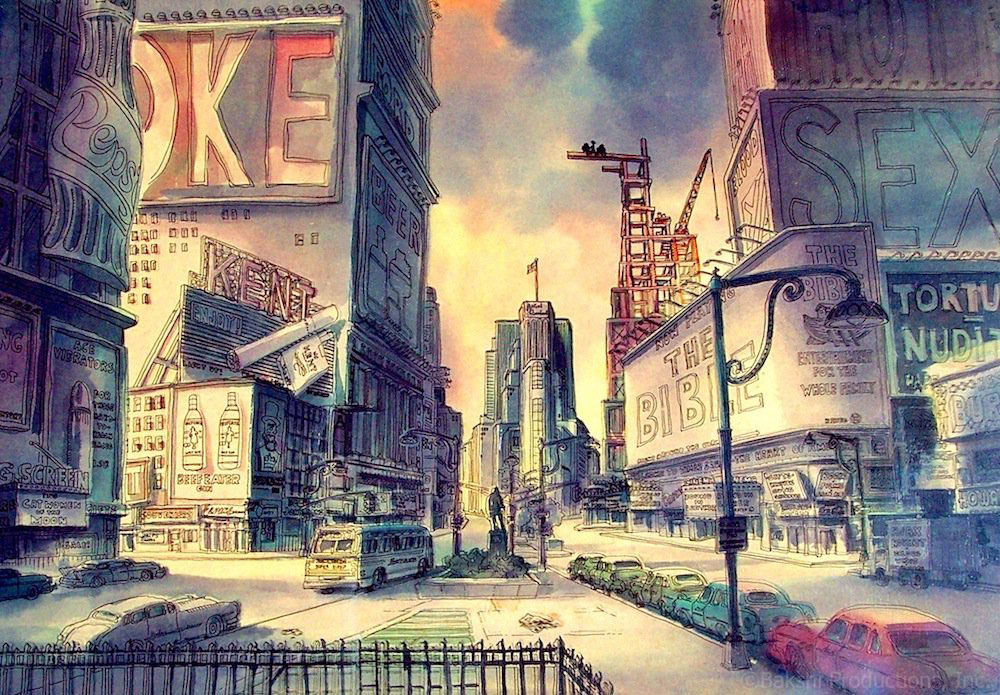

From: 'Fritz the Cat'. Artwork by background artist Johnny Vita.

Krantz Films & Bakshi Productions

In 1966, Steve Krantz established the animation studio Krantz Films, producing various animated TV series, among them Ralph Bakshi's 'Rocket Robin Hood' (1966-1969). One artist who animated on this latter show was Monty Wedd. Krantz also produced the second and third season of the animated TV series 'Spider-Man' (1967-1970), based on Stan Lee and Steve Ditko's comic series. In 1966, Bakshi was promoted to director and, for eight months, ran the Paramount cartoon studios. He enlisted comic artists like Harvey Kurtzman, Wallace Wood, Archie Goodwin, Jim Steranko, Doug Crane and Gray Morrow and created 'The Mighty Heroes' section in the 'Mighty Mouse Playhouse' show (1966-1967). One of the animators on this show was former Terrytoons colleague David Tendlar. However, the studio soon closed down and it turned out that his position was always intended as a temporary vocation. Paramount never even had any intention to produce any of his ideas. As a result, Bakshi ripped up his contract, rejecting the severance package that was offered to him, and went solo.

In 1968, Bakshi founded his own animation studio in Manhattan, produced by Steve Krantz. They originally made animated shorts for advertising and educational purposes. Still, Bakshi felt frustrated. The 1960s and early 1970s were a dark age for animation. Many of the classic Hollywood animation studios closed down and moved into television. The few theatrical cartoons that reached the big screen were hampered by budget cuts. On the small screen, the situation was even worse. Cheaply produced animated series were purely marketed to children. Bakshi was tired of seeing the same old animation clichés. He wanted to make something different, intended for adult viewers.

Fritz the Cat

Bakshi originally considered an animated feature about his personal background. The picture would be strictly marketed towards adults. However, producer Steve Krantz suggested adapting something with name recognition. Bakshi was familiar with the underground comix movement and Robert Crumb's fame within that scene. He approached Crumb to discuss a film version of his best-known series 'Fritz the Cat'. The comics revolved around a lewd cat who was only interested in sex and taking drugs. These were the mature themes Bakshi wanted to explore in animation. Unfortunately, Crumb was reluctant and eventually backed down. His only creative suggestion was that Bakshi should voice Fritz himself. But in the end, Bakshi only voiced one character: the dopey-sounding pig policeman. Without Crumb's name on the contract, the project seemed stranded. But his wife Dana eventually signed the document in his name. Sources differ whether she did it behind his back - because they needed the money - or whether Crumb merely let her do it, so he could escape personal responsibility. Either way, he always maintained he was too young and gullible at the time to simply refuse Bakshi's proposal.

During production of 'Fritz the Cat', Bakshi had difficulty assembling a crew. Some job applicants merely wanted to draw dirty scenes, but lacked skill. Others morally objected to animating graphic violence and sex scenes. They were rejected, fired or quit on their own terms. Eventually Bakshi managed to hire an impressive list of veteran Hollywood animators from studios like Terrytoons, Warner Brothers, Hanna-Barbera, Famous Studios, Fleischer Brothers and even Walt Disney. Most were accessible since the major studios, except Disney, had closed down by that point and the animators were looking for work. Among the veterans working on 'Fritz the Cat' were Fred Abranz, Cliff Augustine, Ted Bonnicksen (who was already terminally ill with leukemia during production and died before the film was completed), John Gentilella, Manny Gould, Volus Jones, Dick Lundy, Norm McCabe, Manuel Perez, Larry Riley, Virgil Ross, Rod Scribner, Irv Spence, Nick Tafuri, Martin B. Taras and Jim Tyer. Some were thrilled to animate taboos they had never been allowed to before.

Bakshi wanted to avoid limited animation and instead bring back full animation from the Golden Age (1930-1960). To save on ink and paint, he considered moving his studio from New York City to Mexico, but the animators' union told him this was illegal. They advised him to move his studio to Los Angeles, which Bakshi did in 1971. Another obstacle was finding investors. Most studios couldn't understand how an animated film could be anything but children's entertainment and freaked out when they saw the animated sex scenes. In the end, Bakshi found a small distribution company, Cinemation, who were willing to take risks. A record company and Playboy publisher Hugh Hefner made extra investments. After a long production period, 'Fritz the Cat' was finally released on 12 April 1972. It easily became a cult movie, but to the surprise of many it also received critical acclaim and eventually became a box office hit. Made for only 850.000 dollars, it earned almost 90 million (!) dollars. No other independent animated film had ever had such success.

'Fritz the Cat' owed much of its ticket sales to the scandal and novelty of being the "first cartoon for adults". In reality, this status is debatable. 'Eveready Harton in Buried Treasure' (1929) was a silent, black-and-white animated short filled with sex jokes, intended to be shown at private parties. According to Disney animator Ward Kimball, it was made by the Raoul Barré, Max Fleischer and Paul Terry studios in a rare collaboration. Another mature animated short, made by Bob Clampett in 1938, featured Porky Pig saying "son of a bitch!" after hitting his thumb with a hammer. But this short was also intended for private enjoyment and never released to the general public. During the Golden Age of Animation (1928-1960), there had been animated series intended for adult viewers as much as children, like the Looney Tunes cartoons at Warner Brothers and Jay Ward's TV series 'Rocky & Bullwinkle' (1959-1964). Both Max and Dave Fleischer's 'Betty Boop' cartoons, as well as Tex Avery's films at MGM, contained sexual innuendo. The 'Night on Bald Mountain' sequence in Disney's 'Fantasia' (1940) also features a few nude breasts. During World War II, various cartoon studios made propaganda shorts ridiculing Hitler, Mussolini and Tojo, all more intended for adult audiences than children. John Halas and Joy Batchelor's animated version of George Orwell's 'Animal Farm' (1954) - with contributions by Harold Whitaker, Brian White, Bill Mevin and Reginald Parlett - was a political drama.The 1960s brought more adult animation in the picture. The Beatles animated feature 'Yellow Submarine' (1968) by George Dunning, with designs by Heinz Edelmann, featured psychedelic imagery and rock music, aiming at youngsters. Various low-budget underground cartoons like Ward Kimball's 'Escalation' (1968), Marv Newland's 'Bambi Meets Godzilla' (1969) and Whitney Lee Savage's 'Mickey Mouse in Vietnam' (1969) were brutal in their depiction of politics and violence. In Terry Gilliam's cartoons for the surreal TV sketch show 'Monty Python's Flying Circus' (1969-1974), occasional nudity and graphic violence could be seen.

But 'Fritz the Cat' made all previous 'adult' cartoons look tame in comparison. It had a much higher budget and far more professional look. It also went much further in its subject matter, with uncompromisingly frank depictions of sex, drugs, vulgar language, bloody violence and death. The film is as anti-Disney as possible, even attacking the company directly in a few scenes. In one, Fritz fantasizes about sex with a pink woman - reminiscent of the 'Pink Elephants' sequence from 'Dumbo'. The crows, who just like in Crumb's original comic, represent African-American people, are equally reminiscent of the African-American crows in 'Dumbo'. In another scene, a pig policeman shows a picture of his "kiddies", depicting three piglets similar to Disney's Three Little Pigs. Later, when the U.S. Air Force bombs a ghetto to suppress a riot, silhouettes of Mickey Mouse, Donald and Daisy Duck can be seen cheering, representing the "establishment". The counterculture edginess in 'Fritz the Cat' is further highlighted by biting satire of the police, college education, religion and racial tensions. Regular viewers were thrilled, surprised or shocked by its audacity. Some audiences couldn't handle adult topics in a medium that had always seemed family friendly. Others welcomed all the broken taboos as a breath of fresh air. At the time, the MPA didn't quite know how to rate 'Fritz the Cat' and settled on an X rating, something usually reserved for downright porn, which Baskhi's film obviously wasn't. Nevertheless, it went down in history as the first animated film to receive an X rating, which likely increased its publicity and box office revenue. Yet by modern-day film rating standards, it would arguably just receive an R or NC-17 rating (not allowed for anyone under 17, unless accompanied by an adult).

Whether one liked or hated it, nobody could deny that 'Fritz the Cat' is a milestone in animation history. Even outside the shock value, it is an innovative piece of cinema. Bakshi used dynamic camera angles and atmospheric musical mood pieces. He made several photos of streets in New York City and traced them with a Rapidograph pen afterwards, so they could be drawn onto cells. In others, the animation is combined with these photos and live-action footage. Some scenes are overlapped with shadow and smog effects, providing a sleazy, ominous atmosphere, like the intermission where a crow grooves to Bo Diddley's song 'Bo Diddley'. Bakshi also recorded real-life conversations with people in bars and his father's synagogue and used them in the film. Bakshi also tried to do more than just bawdy comedy. Some scenes evoke strong emotional drama. When Duke the crow is shot during a police riot, his slow and painful death is visualized by billiard balls rolling to stagnation. Heartbeat sounds and rioters' yells around him blur into a disturbing soundscape until he perishes alone in the chaos.

Film posters for 'Fritz the Cat' and 'Wizards'.

Reaction of Crumb to Bakshi's 'Fritz the Cat'

Thanks to Robert Crumb's counterculture fame, 'Fritz the Cat' brought many art students, cartoonists and youngsters to film theaters. Yet fans were divided as to whether Bakshi actually captured the feel and intent of the original comics. Some defended the picture as a well-executed adaptation. Others felt it sometimes strayed too far from Crumb's vision, going out for shallow shock and sleazy sex jokes. Some viewers made the incorrect assumption that Crumb had been actively involved in its production, even directing it. In the satirical magazine National Lampoon, Michael O'Donoghue and Randall Enos spoofed 'Fritz the Cat' in a parody comic, portraying Crumb as a shameless sell-out. In 1976, Robert Romagnoli spoofed Crumb's other signature comic 'Mr. Natural' in the magazine Punk as 'Mr. Neutral', with the guru wondering: "Maybe one day I'll hit it big in the movies... like the fuckin' cat did". Crumb actually read Romagnoli's comic and was so offended that he discontinued 'Mr. Natural' for a full decade. Crumb's second wife, Aline Kominsky, recalled her mother once asking her husband on the phone "whether he still made animated movies, like 'Felix the Cat'?". She also included this anecdote in their collective comic book 'Dirty Laundry Comix 2' (January 1978).

In reality, Crumb never visited the animation studio or informed himself about the production process. Unsurprisingly, he hated the film afterwards, vocally distancing himself from it in many interviews. He disliked the look, the atmosphere and felt its political messages went against his own convictions. Some sources have incorrectly claimed that he had his name removed from the posters and credits. In reality, this didn't happen, but Crumb did draw a new comic story, 'Fritz the Cat Superstar', published in People's Comics (Golden Gate Publishing, September 1972), only five months after the film's premier. It portrays Fritz as a decadent Hollywood star: a mere pawn in the hands of sleazy executives "Ralphie and Stevie". In the final scene, a disgruntled girlfriend murders Fritz with an icepick. In a severe case of creator backlash, Crumb never drew another 'Fritz the Cat' story again.

Bakshi always insisted that he had nothing but good intentions. Several dialogues in the movie are taken line by line from the original stories, like 'Fritz Bugs Out', 'Fritz the No-Good' and a few untitled tales. He deliberately used jazz and blues on the soundtrack, since he knew that Crumb loved this music. He also pointed out that Crumb received a bigger share from the box office profits than he ever did, even though it was only five percent. In the end, since the underground comix artist was never available for feedback, Bakshi had to make his own artistic choices, but didn't mind, since he wanted to be taken seriously as a cinematic "auteur": "At that point I was making Ralph Bakshi's 'Fritz the Cat', rather than Crumb's." Indeed, some scenes, like Fritz causing mayhem in a synagogue, were completely created by Bakshi.

Despite Crumb's efforts, an animated sequel still came out: 'The Nine Lives of Fritz the Cat' (1974). He tried to sue, but contractually a sequel was part of a clause, so he was forced to drop his case. As he commented in the 1987 documentary 'The Confessions of Robert Crumb': "You can't win...' Though, contrary to popular thought, Bakshi had nothing to do with 'The Nine Lives of Fritz the Cat' either. He was uninterested in sequels, as he didn't want to repeat himself. Producer Steve Krantz simply put another director, Robert Taylor, in charge. 'The Nine Lives of Fritz the Cat' is an anthology film, loosely based on a few unadapted 'Fritz' stories, but otherwise taking colossal liberties with Crumb's original character. In one storyline, for instance, U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger is U.S. President and fights a war against the Black Panther Party, who now have their own independent country. Critics and audiences hated 'The Nine Lives of Fritz the Cat' in equal measure, which sealed the milking of Crumb's cat for good. Only years later did 'The Nine Lives of Fritz the Cat' develop a small cult following of its own. Some fans enjoy its wild and unpredictable narratives.

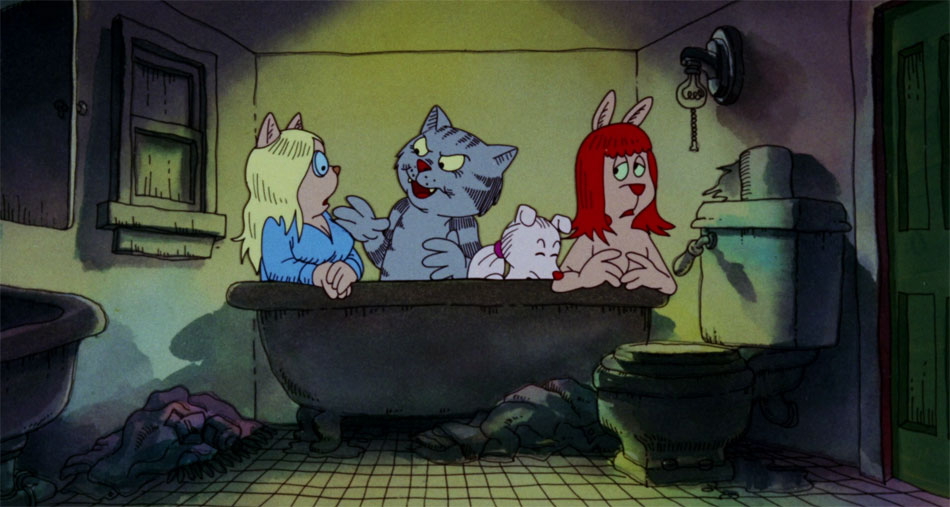

Still from 'Heavy Traffic'.

Heavy Traffic

After 'Fritz the Cat', Bakshi could finally direct the picture he always wanted. He was fed up with most animation being built around an anthropomorphic animal, whose wacky tales then form the plot. So he went for a more autobiographical route, comparable to a live-action 'auteur' drama. 'Heavy Traffic' (1973), is set in New York and follows a young wannabe animator, who still lives with his parents. His Italian-American father is an adulterous drunk who always fights with his Jewish wife. More than one modern viewer has noticed that the dad shows an interesting resemblance to Matt Groening's Homer Simpson, created 15 years later. Besides parental fights, Michael's neighborhood is ravaged by junkies, mobsters, transvestites, prostitutes and black, Jewish and Italian-American hoodlums. His African-American girlfriend Carol is a frequent victim of racism. But he tries to survive and find a way out. Much like its predecessor, 'Heavy Traffic' received an X-rating and mixed reviews, but still did well at the box office. Fans liked the personal touch and it achieved cult status. Ironically, Bakshi only earned 10% of what producer Steve Krantz made, so he deliberately distanced himself from Krantz and sold his next script, 'Coonskin', to a different producer: Albert S. Ruddy, best known for 'The Godfather' (1972). Krantz suspended Bakshi and afterwards forced him to finish 'Heavy Traffic'. After a month of arguments, Bakshi agreed and was allowed to leave his contract afterwards.

Coonskin

For his next animated feature, 'Coonskin' (1975), Bakshi made an updated version of Joel Chandler Harris' book 'Uncle Remus' and the 1946 Walt Disney adaptation of that same story, 'Song of the South'. In the original, a black slave, Uncle Remus, tells children stories about a trickster rabbit, Br'er Rabbit, and his enemies, Br'er Fox and Br'er Bear. The Disney movie blends live-action with animation to portray an idyllic dream world. In 'Coonskin', Bakshi uses the same techniques to make a blaxploitation movie, set in dreary, present-day Harlem, New York City. Br'er Rabbit, Fox and Bear are now three African-American friends. They are confronted with poverty, racism and exploitation, both by racist whites and opportunistic blacks. Outraged and disgusted, the trio decides to fight back. 'Coonskin' was also more ambitious in its scope. The film is a satire of every possible stereotype about African-Americans, particularly the ones manufactured in Hollywood. The story is intercut with metaphorical allegories about the status of blacks in "the land of the free". Thanks to the profits from his previous movies, Bakshi could cast three celebrity actors, Scatman Crothers (the narrator), soul singer Barry White (Br'er Bear) and - in an uncredited role - Al Lewis (The Godfather). Philip Michael Thomas, the actor who played Br'er Rabbit, would later gain fame as detective Ricardo Tubbs in the TV series 'Miami Vice'.

Unfortunately, 'Coonskin' 's provocative title led to many people assuming it was a racist film. Many misinterpreted its satirical use of black stereotypes, like the dancing "coon", the Mammy and black preachers, boxers, basketball players, doowop choirs, prostitutes, pimps and big-lipped "jive" talking Uncle Tom characters. Protest groups picketed it, some at the instigation of African-American reverend Al Sharpton, who hadn't even seen the film. Bakshi once observed how some of Sharpton's picketers watched the film and turned against Sharpton, since they liked the picture. Many were surprised that almost all of the animators who worked on 'Coonskin' were in fact black, safe for Bakshi. But at the time, all the controversy not only hurt the film's box office profits, but also its reputation. For more than a decade it sank into obscurity, since no theater or channel dared to screen it. In the late 1980s, 'Coonskin' was released on video under a different title, 'Streetfight'. It finally picked up a cult following, also among celebrity fans like directors Spike Lee and Quentin Tarantino. Various rappers sampled its dialogue, like in the songs 'Crime Scene' (2011) by Dominic Owen and 'Hooked' (2013) by Sir Own. In the 2000s, 'Coonskin' received a proper DVD release under its original title and was recognized as a masterpiece. Many Bakshi fans still consider 'Heavy Traffic' and 'Coonskin' to be the director's best work.

Still from 'Coonskin'.

Wizards

Near the end of the 1970s, Bakshi took a different turn. He directed two fantasy films which had a more family friendly tone: 'Wizards' (1977) and 'Lord of the Rings' (1978). 'Wizards' is set in a post-apocalyptic future, where two wizards combat each other. One uses traditional magic, the other modern technology and Nazi propaganda film footage. 'Wizards' featured graphic contributions by cartoonists Ian Miller and Mike Ploog. At the request of George Lucas, who was directing 'Star Wars' at the time, Bakshi shortened his original title, 'War Wizards' to 'Wizards'. In exchange, Mark Hamill (Luke Skywalker in 'Star Wars') was allowed to voice an elf in 'Wizards' in between filmings. 'Wizards' did well with viewers, just like 'Star Wars'. Unfortunately, film theaters now started programming George Lucas' SF saga, rather than provide screens for 'Wizards', which prevented it from making its money back. The picture nevertheless reached cult status later.

Lord of the Rings

Bakshi's other fantasy film was 'Lord of the Rings' (1978), an ambitious adaptation of J.R.R. Tolkien's novel cyclus 'The Lord of the Rings' 1978). In the mid-1960s, Czech animation legend Jiri Trnka, illustrator Adolf Born and cartoon director Gene Deitch had tried to make an animated version, but never went further than one reel. Producer William L. Snyder merely wanted them to make a cartoon adaptation so he could keep the film rights, as stipulated in his contract. Bakshi managed to make a 'Lord of the Rings' animated feature, but only got as far as the first of the three books. Another criticism was that the majority of the movie was rotoscoped. The picture received mixed reviews. Still, for more than 20 years, Bakshi's work was the only available film version of 'Lord of the Rings' and therefore easily became a cult movie. The picture was also parodied in Mad Magazine issue #210 (October 1979) by Frank Jacobs and Mort Drucker as a musical, under the title 'The Ring and I'. When Peter Jackson made his live-action version in 2001-2003, he managed to adapt all three novels of the trilogy. Because of this, Jackson's version has overshadowed Bakshi's version in the eyes of most Tolkien fans.

Since 'Wizards' and 'Lord of the Rings' were fantasy films with a more family friendly tone, they disappointed fans of Bakshi's raunchier and more personal work. Nevertheless, the films paved the way for several other sword & sorcery animated features in the early 1980s, including Gerald Potterton's 'Heavy Metal' (1981), Don Bluth's 'The Secret of Nimh' (1982), Arthur Rankin Jr. and Jules Bass' 'The Last Unicorn' (1982) and Hayao Miyazaki's 'Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind' (1984). Even the Disney Studios made an attempt at a more mature fantasy adventure picture, 'The Black Cauldron' (1985).

Work in the 1980s

The 1980s saw Bakshi making two animated films which expressed his love for music: 'American Pop' (1981) and 'Hey Good Lookin'' (1982). 'American Pop' is partially a history of popular music, intercut with rotoscoped concert footage. One of the background and character designers was comic veteran Russ Heath. 'American Pop' had a good critical reception and financial profit, although once again its reliance on rotoscoped animation was criticized. 'Hey Good Lookin'' was based on Bakshi's teenage years during the 1950s. Having been in production since the mid-1970s, it was stylistically closer to his earlier films. But this stop-and-start approach gave the completed picture a messy, slowly paced feel and 'Hey Good Lookin'' flopped. It only picked up a cult following later. Quentin Tarantino even deemed it a better movie than 'Heavy Traffic'.

With 'Fire and Ice' (1983), Bakshi returned to fantasy. In the wake of the box office success of 'Conan the Barbarian' (1982) starring Arnold Schwarzenegger, 'Fire and Ice' featured a collaboration with 'Conan' book illustrator Frank Frazetta to co-design the main characters. Comic writers Gerry Conway and Roy Thomas, from the Marvel adaptations of 'Conan', penned the screenplay. James Gurney and Thomas Kinkade painted backgrounds. The picture once again never rose above cult status. In 1985, Bakshi's studio directed the animated segments of the 'Harlem Shuffle' (1985) music video by the Rolling Stones.

Return to television

In 1987, Bakshi returned to television by supervising 'Mighty Mouse: The New Adventures' (1987-1988) on CBS, based on Paul Terry's cartoon character. The series gained good reviews, particularly thanks to one of his directors, John Kricfalusi, who tried to make the animation look more expressive and different than most other TV cartoon shows at the time. Bakshi made sure that his animators had complete creative freedom and shielded them from the censors and producers. Unfortunately, the series was canceled after a year, because religious activist Donald Wildmon objected to a scene in which the mouse apparently sniffed cocaine. In reality it was just a flower. In 1989, Bakshi Productions animated Dr. Seuss' 'The Butter Battle Book' for which the famous children's author also wrote the screenplay. Seuss paid Bakshi a huge compliment by claiming it was the best screen adaptation of his work he ever saw.

Animation cell from 'Cool World'.

Cool World

Bakshi's final film was 'Cool World' (1992). Originally intended as a story about a cartoon character and a real person who have sex and whose child was a mutated freak, the studio scrapped the entire idea. Instead they made a much tamer story about a cartoonist (Gabriel Byrne) chased by a detective (Brad Pitt), because of his relationship with an animated girl from a parallel cartoon universe. The comic strips in the film were drawn by Spain Rodriguez, while Mark O'Hare was a storyboard artist. The studio tried to sell 'Cool World' as a 'Who Framed Roger Rabbit' clone and heavily implied in their tagline that there would be a sex scene. Since it failed to deliver on both premises, the picture became a colossal flop. It did spawn an official comic book adaptation, released by DC Comics to coincide with the film's premiere. The 'Cool World' comics were scripted by Michael Eury, drawn by Stephen DeStefano, Chuck Fiala and Bill Wray, while Bakshi designed the covers. They only lasted four issues.

Later career

In 1994, Bakshi directed his first and only live-action film, the forgettable 'Cool and the Crazy'. A similar fate met 'Spicy City' (1997), an adult animated TV series set in a dystopian future. Since then he only made one animated short, 'Last Days of Coney Island' (2015), a neo-noir film set in New York City. It was released exclusively online on the video site Vimeo. He founded the Bakshi School of Animation and Cartooning in 2003, and has focused largely on painting since. In the episode 'Fire Dogs' of John Kricfalusi's 'Ren & Stimpy: The Adult Party Cartoon', Bakshi voiced the fire chief, a character who already appeared in the original 1991-1995 'Ren & Stimpy' series, based on him. In 'Fire Dogs 2', the fire chief was even deliberately physically remodeled to look completely like Bakshi.

Bakshi's animators

Among the people who were once employed at Bakshi's productions are Nancy Beiman, Jerry Brice, Nick Cuti, Jim Davis, Jaime Diaz, Tim Gula, Cheese Hasselberger, Mike Kazaleh, John Kricfalusi, Don Morgan, Mark O'Hare, Mike Ploog, Andrew Stanton, Martin B. Taras, David Tendlar, Bruce Timm, John(ny) Vita and Wendell Washer. Future film director Tim Burton also worked for Bakshi in the late 1970s, as his first job after leaving college.

'Cool World' comics, DC Comics, 1992.

Recognition

Ralph Bakshi won a National Cartoonists Society Division Award (1978), a Golden Gryphon (1980) at the Giffoni Film Festival for 'Lord of the Rings', an Annie Award for Distinguished Contribution to the Art of Animation (1988), a Winsor McCay Award (1988), a Maverick Tribute Award (2003) and an Inkpot Award (2008).

Legacy and influence

Ralph Bakshi has always been a polarizing director. Plagued by budget problems, time restrictions and executive meddling, few of his films came out the way he envisioned them. As a result, some of his storylines can leave a messy, unfocused and at times incomprehensible impression. In order to properly finish them, he often had to resort to adding photographs, live-action footage or rotoscoping. He did this so frequently that viewers have regularly wondered why he just didn't make an actual live-action film instead. Despite his association with rotoscoping, Bakshi only used it out of necessity. He disliked the technique, but it at least allowed him to finish his pictures. Overall, Bakshi was unconcerned with visual perfection. He despised the Disney esthetic that high production values and slick appeal are necessary to make a good animated film. In his observation, hundreds of animators have let themselves be unnecessarily discouraged by this unwritten "law". In Bakshi's films, occasional off-model mistakes, continuity errors, bad synching and less fluid animation are quite common. Some designs and imagery would be considered ugly in the eyes of viewers used to Disney standards. But to him, atmosphere and attitude were always far more important.

Bakshi also suffered from undeserved bad publicity. For decades his name was synonymous with "animated porn", mostly with people who never looked past the nudity. The success of 'Fritz the Cat' paved the way for many adult animated pictures with low-brow sexual content, like David Grant's 'Snow White and the Seven Perverts' (1973), Gibba's 'Il Nano e la Strega' ('King Dick, 1973), Charles Swenson's 'Down and Dirty Duck' (1974), Picha's 'Tarzoon, La Honte de la Jungle' (1975), Don Jurwich's 'Once Upon a Girl...' (1976) and Gerald Potterton's 'Heavy Metal' (1981). At a certain point every cartoon with nudity or adult themes was attributed to him, even if he had nothing to do with it. Since so many of these pictures were forgettable trash to make teenage boys snicker, his reputation suffered even further. Many people to whom animation was nothing but a children's medium regarded him as a sleazy pervert who wanted to corrupt young kids with "depraved sex cartoons". As a result, he found it increasingly difficult to find funding and distributors for his new projects. Even when he made normal children's TV films and series, there were still people who protested, purely based on his "adults only" reputation.

As time went by, Bakshi's fan base grew. His movies were rediscovered and newly appreciated as some of the few original and artistically interesting works during the Dark Age of Animation (1960-1988). In an era when most other cartoons lacked originality or vision, Bakshi at least offered an alternative. He moved away from the idea that everything had to mimic Disney. Rather than tell child friendly stories about funny animals, he made pictures about mature themes. Instead of making escapist fairy tales, he presented worlds set in the harsh reality of everyday life. Contrary to most cartoon studios, he didn't make a slick, uniform, bland factory product, but works with a strong, edgy, personal vision. By not compromising or pandering to mass audiences, he was praised as a maverick filmmaker, operating outside the Hollywood system. Several of his movies have therefore stood the test of time as cult classics.

Likewise, Bakshi's historical stature has grown too. He was a pioneer in adult animation. From the late 1980s, early 1990s on, several animated TV shows with more mature themes became possible thanks to his influence: Matt Groening's 'The Simpsons' and 'Futurama', John Kricfalusi's 'Ren and Stimpy', Mike Judge's 'Beavis & Butt-head' and 'King of the Hill', Everett Peck's 'Duckman', Trey Parker and Matt Stone's 'South Park' and Seth MacFarlane's 'Family Guy' and 'American Dad'. In 'The Simpsons' episode 'The Day the Violence Died' (1996), his work was even spoofed in a segment named 'Itchy & Scratchy Meet Fritz the Cat.' On the Internet, many online cartoon series have also delved into mature themes. As Bakshi once said: "Baby, I'm the most ripped-off cartoonist in the history of the world, and that's all I'm going to say."

Books about Ralph Bakshi

Artwork from Bakshi's animated cartoons and comics can be read in the highly recommended book 'Unfiltered: The Complete Ralph Bakshi' (Universe, 2008) by Chris McDonnell and Jon M. Gibson, which has a foreword by Quentin Tarantino.