'Big Blown Baby' #4 (November 1996).

William Wray is an American cartoonist and animator who signs his comics and cartoons with "Bill Wray", and his landscape paintings with his full name. He is best known as an animator working for John Kricfalusi's cult series 'Ren and Stimpy' (1991-1995). As a comic artist, his signature series was 'Monroe' (1997-2006), written by Tony Barbieri and published in Mad Magazine. It starred the world's most unlucky teenager and was notable for its gritty tone. Although 'Monroe' polarized readers at the time, it also acquired a cult following. Together with Mike Mignola, Wray also made a younger version of the character 'Hellboy' named 'Hellboy Junior' (1997). Wray is also co-creator of the hilarious 'Big Blown Baby' (1996) for Dark Horse.

Early life and influences

William York Wray was born in 1956 in Fort Meade, Maryland, as the son of a lieutenant-colonel who worked for army intelligence. Because of his job, his father often moved across the globe. Apart from the United States, Wray also spent his youth in Germany, Vietnam and Hong Kong before eventually settling in Costa Mesa, California in 1966. Wray often felt lonely, which motivated him to read comics, watch cartoons, collect Monster Gum cards and make drawings. His mother was an accomplished amateur painter and often took him to museums and modern art shows. Among his graphic influences were painters like Frank Brangwyn, Richard Bunkall, Dean Cornwell, Nicolai Fechin, Emil Gruppe, J.C. Leyendecker, Edgar Alwin Payne, Ray Roberts, Edward Seago, Raimonds Strapans and N.C. Wyeth. Wray also admires animators such as Bob Clampett, Chuck Jones, Tex Avery and Hanna-Barbera and comic artists like Frank Frazetta, Jack Kirby, Hank Ketcham, Harvey Kurtzman, Erich Sokol and Wallace Wood. Wray studied at Orange Coast College, but dropped out because he was never taught any valuable artistic techniques.

'Scritch... Scritch... Scritch...' (Twisted Tales #5, October 1983).

Animation career

Wray worked as a professional animator and lay-out artist for the Walt Disney Company, Hanna-Barbera and Filmation during the so-called "Dark Age of Animation" (1960-1989), when most cartoons were made for forgettable, uninspired and low-budget TV series. Among the few memorable shows he animated on were 'Fat Albert and the Cosby Kids' and 'He-Man'. During evenings and weekends, he took classes from a former Disney animator, who taught him far more valuable skills than any of the schools he attended. He also met John Kricfalusi, who shared the same sentiments about the current animation industry. Both men worked as partners on several animated shorts for TV commercials and cable TV. One of these, 'Ted Bakes One' (1979), about a chicken who tries to squeeze out an egg. actually got sold to cable, but failed to make an impact.

While working at Hanna-Barbera in the early 1980s, Kricfalusi drew a one-page comic, 'Cave Nudes', inked by Wray, starring 'The Flintstones'. The gag features the familiar running gag where the mail boy throws a stone newspaper at Fred, knocking him down. Here, however, Fred is knocked out, while the paper boy has sex with Wilma, much to her delight. Kricfalusi signed the work with a pseudonym, "Billy Bunting" and hung a copy on every wall of the studio's producer's wing as a way of rebellion. According to legend, all copies were collected by his colleagues in less than an hour. The comic gained wider notability when published in Weirdo issue #9 (Winter 1983). By 1985, Wray was so fed up with the way things were going at Hanna-Barbera that he left animation and moved to New York City.

'Metamorphfloozie' (Wasteland #14, Winter 1988).

Comics work in the 1980s

In New York City, Wray spent most of his time painting and doing comic book work. He had done his earliest comics work at the East Coast, when he contributed to the anthology comic 'Twisted Tales' by Pacific Comics (and later Eclipse) in 1983-1984. By 1985, Wray published a story in issue #146 of Creepy by Harris Comics, and subsequently contributed to 'Alien Encounters' (1985-1986) and 'Doc Stearn... Mr. Monster' (1987) of Eclipse Comics. In 1989, he illustrated the true story of author Ramsey Campbell's relationship with his mother and her dementia called 'At The Back Of My Mind' for Eclipse's horror anthology 'Saturday Mourning: Fly In My Eye'. He did work on 'Star Trek' (1987), 'The Outsiders' (1987) and John Ostrander's horror anthology series 'Wasteland' (1988) for DC Comics. He most notably worked on DC's comic books and anthology with Steve Ditko's 'The Question' (1989). Together with Keith Giffen, he made a comic book for DC based on Lobo's dog, but the project was shelved because of its bad taste in humor. He additionally contributed to Marvel's 'Video Jack' (1988), 'Open Space' (1989), 'Clive Barker's Hellraiser' (1991) and 'What The--?!' series (1991). Wray also regularly contributed illustrations and short stories to the humor magazine Cracked (1986-1988).

Typical Bill Wray close-up for the 'Ren & Stimpy' episode 'Stimpy's Cartoon Show' (1994).

Ren & Stimpy

Wray honed his skills by taking courses at the Art Students' League. In 1991, he joined his former colleague John Kricfalusi to work on his animated TV series 'The Ren and Stimpy Show' (1991-1995), produced by their own company Spümcø. Its combination of gross-out comedy, surreal plots and subversive, often nerve-wreckingly intense content polarized viewers, but also grew a strong cult following. Wray was one of the head animators and together with Kricfalusi and writer Bob Camp the creative triumvirate. He was background art editor, storyboard artist and background color stylist in many episodes, providing moody atmospheres. One of his specialities were the gruesome painted close-ups which were often used during dramatic scenes.

In 1992, when Kricfalusi was fired from his own show, he and Bill Wray had a falling out. Previously, Kricfalusi had strongly discouraged any of his animators to work on a series of monthly comic book adaptations of 'Ren & Stimpy', published by Marvel, since he felt the artwork looked atrocious. Yet now that he had burned bridges with Kricfalusi, Wray no longer saw any qualms in working on the 'Ren & Stimpy' comics. In total, Marvel published 39 'Ren & Stimpy' titles, from November 1995 on under the Marvel Absurd imprint. The final issue came out in July 1996.

Big Blown Baby

With Robert Loren Fleming, Wray created the comic book series 'Big Blown Baby' (1996) for Dark Horse Comics. The comic book had the same vile and hilarious humor as the 'Ren & Stimpy' series. It featured a disgusting extraterrestrial baby-like creature who crash lands on Earth. Dark Horse published a trial issue in its 'Dark Horse Presents' series (#106) in 1996, and then released four independent comic books later that year.

Hellboy Jr.

In October 1997, Wray illustrated Mike Mignola's two-issue mini-series 'Hellboy Junior', a humorous younger version of Mignola's own 'Hellboy'. The series won Mignola the Eisner Award for Best Writer/Artist: Drama (1998). Wray also wrote narratives and was assisted by Stephen DeStefano, Hilary Barta, Dave Cooper, Pat McEown, Glenn Barr and Kevin Nowlan.

'Sparky Bear' (Hellboy Jr. #2, 17 November 1999).

Comics based on animated series

Wray drew several comics based on animated TV series, broadcast on Cartoon Network. These included stories with Hanna-Barbera's 'The Jetsons' for DC's 'The Flintstones and the Jetsons' (1997) and 'Cartoon Network' (1998), as well as covers and some interior stories based on Genndy Tartakovsky's 'Dexter's Laboratory' (2000-2004). In 2003, he also wrote two episodes for this series.

Animation career in the 1990s and 2000s

Wray was a character designer for the comedy film 'Space Jam' (1996) and designed backgrounds and lay-outs for the animated TV series 'Samurai Jack' (2001-2004) and 'The Mighty B.' (2008-2001). For the latter show, he also acted as a supervising director. With Tartakovsky and co-artists Lynn Naylor and Mike Manley, Wray additionally made a 55-page comic story for DC's 'Samurai Jack Special' (2002). Wray was a writer and storyboard artist for 'The Woody Woodpecker Show' (1999-2000) based on Walter Lantz' original creation.

Mad Magazine

Between 1996 and 2006, Wray was part of the "usual gang of idiots" at Mad Magazine. He drew parodies of popular TV series, such as 'Single House' (written by Mike Snider, issue #350, October 1996), 'The Antiques Freakshow' (written by Charlie Richards, issue #381, May 1999), and with scriptwriter Dick DeBartolo: 'Survivor' (issue #398, October 2000) and 'The Weakest Link' (issue #409, September 2001). Naturally, he also tackled films, like 'Patch Adams' (written by Stan Hart, issue #383, July 1999) and 'The Blair Witch Project' (written by Desmond Devlin, issue #387, November 1999).

One of his funniest one-shot comics in Mad was the article 'If Walt Disney Visited His Studio Today' (issue #357, May 1997), written by Chris Hart. The story follows Walt Disney being unfrozen after 31 years and welcomed by Mike Eisner, who was head of the Disney company at the time. He shows Uncle Walt around and explains all the major changes that happened since his death in 1966. The comic is a brilliant satire of the Disney corporation, from the animation studio to the merchandising industry to the theme parks. It provided Wray with a chance to draw depraved versions of all the familiar Disney characters.

'If Walt Disney Visited His Studio Today' (issue #357, Mad Magazine, May 1997), starring Walt Disney and Mike Eisner. In the background we recognize cameos from Tinkerbell, Mowgli, Dumbo, Jiminy Cricket, Woody the cowboy, Buzz Lightyear and Stimpy from 'Ren & Stimpy'.

Monroe

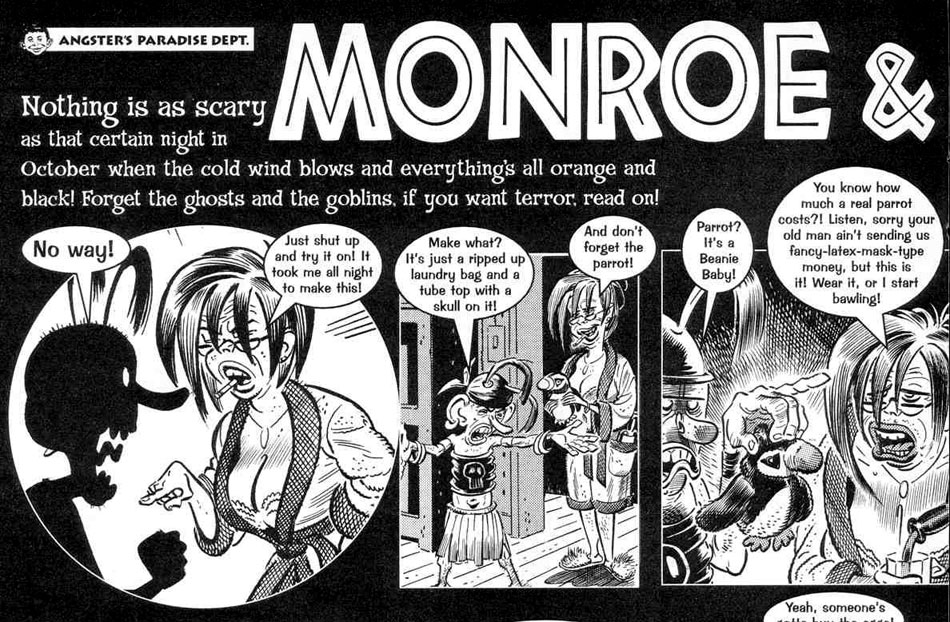

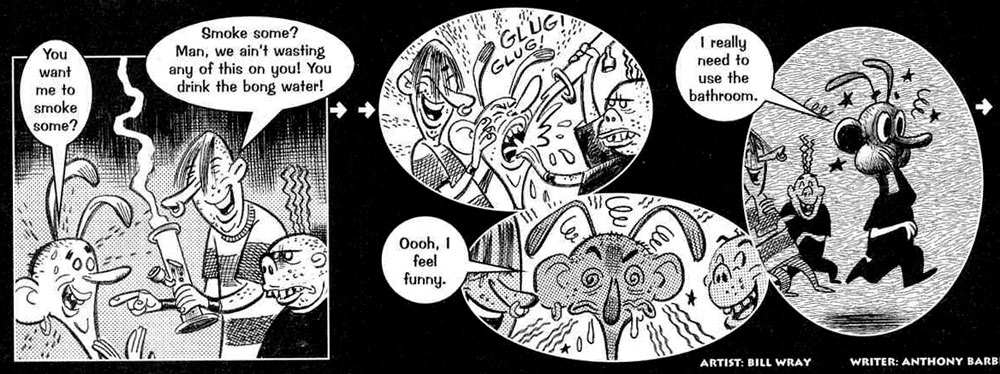

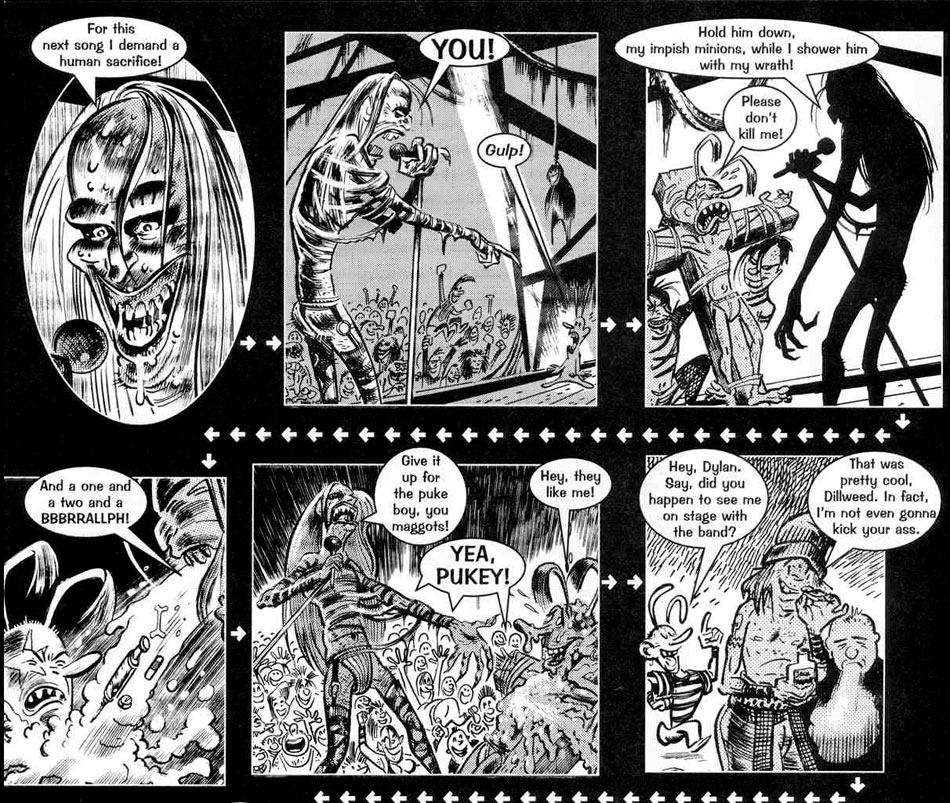

Wray's most significant contribution to Mad was a long-running comic strip named 'Monroe', written by Anthony Barbieri, a former scriptwriter for the humorous talk show 'The Jimmy Kimmel Show'. It debuted in April 1997 in its 356th issue. Monroe is a teenager with two antenna-like hairs on his bald head. Wray was specifically hired by Mad's editors because of his background in comic books. He also edited and lettered everything on his own, instead of letting the editors dictate the font. Originally, Wray drew Monroe's mother as a rather disgusting, chain-smoking character, while Monroe was drawn with a small nose. At the suggestion of the editors, his mum was redesigned as a more attractive housewife, while Monroe received a longer nose. But Wray felt the woman now looked "too clean-cut" and slowly but surely redesigned her back to his original intentions: "They never noticed."

'Monroe', from Mad #375 (November 1998).

In early episodes, Monroe lives with his parents who, later in the series, get divorced. His cranky and senile grandfather later moves in too. Monroe's chain-smoking mother is seen with a different partner in every episode. She is not above prostitution, stripping or online camcorder porn to earn some extra money. Yet she at least gets some enjoyment out of her life. Monroe, on the other hand, is a typical unlucky teenager. He always tries to come across as "cool", earn some badly needed money or get laid. Most of his plans are motivated by his crush on classmate Jolynda, who doesn't like him one bit and takes advantage of the fact that he has the hots for her. Monroe's best friend in school is the geeky bespectacled kid Walter, while his nemesis is Dylan, a bonnet-wearing bully who often beats him up. Dylan often makes jokes at Monroe's expense, which his pals invariably find funny, leading to their eternal catchphrase: "Good one, Dylan!". Even worse: Jolynda is often seen together with Dylan.

Although Monroe often hangs out with his separated father and mother, in later episodes they eventually get back together, but have an open relationship. His mother gets pregnant again and thus Monroe receives a baby brother, Perry. The family remains as dysfunctional as ever, with Monroe's parents usually only using him for opportunistic projects and goals. Just like his teachers and classmates, they have no respect for his wellbeing. Most episodes of 'Monroe' take place at his high school, but the scrawny teen has also been at summer camp and other vacations, from Las Vegas, Disney World to Europe. Needless to say, he rarely gets a happy ending.

'Monroe' (Mad #364, December 1997).

At the time, 'Monroe' was a quite unusual comic strip, even for Mad. The artwork looked more like an underground comic for adults. The comedy was pitch black, with sometimes creepy imagery and near-explicit allusions to sex, drugs and painful violence. Most comics in the magazine had been more subtle regarding these matters. 'Monroe' was also one of the few character-driven series in Mad. Most short stories in the magazine had always been one-shot parodies, except for Antonio Prohias' 'Spy vs. Spy' series and Don Martin's 'Captain Klutz' (which only appeared in their paperbacks). 'Monroe' was also unique in the fact that it centered on somebody with the same age as the target audience. As such, many young readers enjoyed the comic strip and it quickly gained a cult following. Its satirical tone also made it fit right in Mad's pages. 'Monroe' viciously spoofed teenage angst and American high school life. Other episodes directly mock phenomena like Playstation, 'Jackass', 'The Matrix', Marilyn Manson and 'Star Wars'.

In issue #416 (April 2002), one reader nevertheless expressed his dislike of 'Monroe'. In typical Mad fashion, the editors instantly named him "president of the Monroe Fan Club." While intended as a joke, several readers wrote to the magazine, wanting to join this fan club, while others supported the complainer's claim that 'Monroe' ought to be removed from Mad. In issue #419 (July 2002), Mad posted a short overview of the various pros and cons they received by mail. The editors launched another readers poll in issue #441 (May 2004), asking their audience who should become the "next" president of the Monroe Fan Club, which again led to several enthusiastic letters. A notable celebrity fan of the series was Dutch comic artist Marco Kuipers, who sent a fan letter to Mad, published in issue #485 (January 2008), with a photograph of a figurine he had made of Monroe. Another artist who enjoyed 'Monroe' was future Mad cartoonist Tom Richmond.

'Monroe', from Mad #370 (June 1998).

Wray and Barbieri let Monroe grow from a young child into an acne-riddled teenager. On his blog (dated 10 January 2010), Wray revealed that he and Barbieri wanted to let the character grow into a young adult, but the editors forced them to let Monroe stay a teenager. Although Wray described Monroe as "the love of my cartoon life for a long time", it changed when editor Jenette Kahn, who'd greenlighted 'Monroe' back in 1997 and sympathized with Wray, retired. Wray couldn't get along with Kahn's successor, Paul Levitz, who turned the subversiveness of the comic down. For Wray, it slowly but surely "turned into a job", which might explain why the more elaborate artwork of the early years started to become more sketchy and stylized. In the spring of 2006, Wray left Mad.

'Monroe' was put on hiatus for six months. In issue #470 (October 2006), the character made a comeback, still scripted by Barbieri, but drawn and redesigned by a new artist, Tom Fowler. In the 481th issue (September 2007), Fowler received assistance from other artists: Ryan Flanders, followed by Carl Peterson in the 484th issue (December 2007). 'Monroe' ran for four more years until the series came to a conclusion in issue #502 (January 2010).

Painting

Since the mid-2000s, Wray mostly focuses on creating landscape paintings, trying to evoke the skills of the classic old masters. In 2009, he released the book 'Sparrow' (IDW Publishing), written and edited by Ashley Wood.