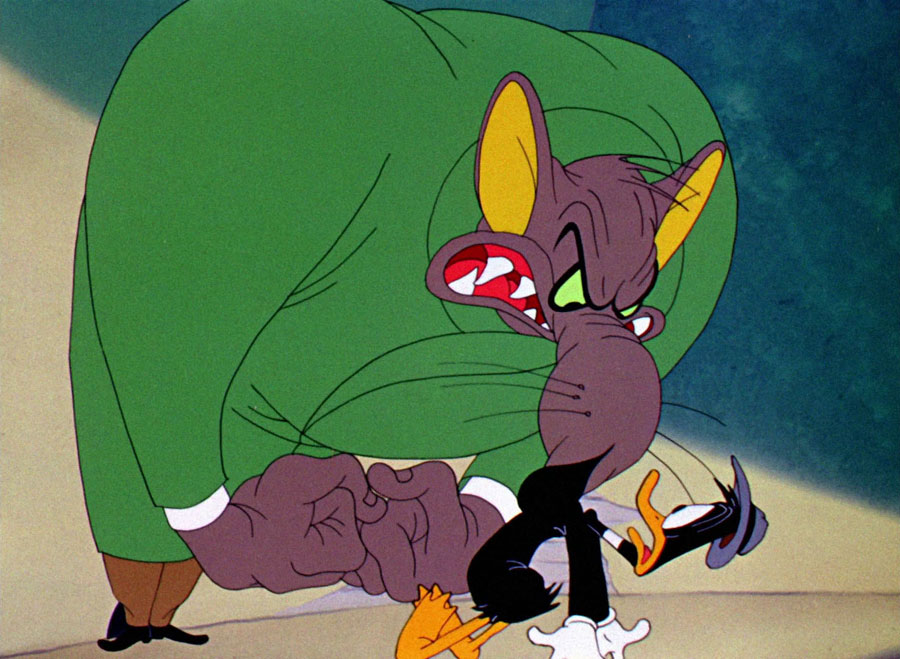

Daffy Duck in 'The Great Piggy Bank Robbery', 1946. Animation by Rod Scribner.

Bob Clampett was an American animation director, most famous for his work at Warner Brothers' cartoon studio between 1936 and 1946. Just like his fellow 'Looney Tunes' directors, he too made many cartoons starring Porky Pig, Daffy Duck and Bugs Bunny. He was the creator of Tweety Bird and minor characters like Beaky Buzzard and Charlie Dog. Clampett additionally invented Daffy's famous upside down jump and "Woo Hoo" call. Another trademark was the "bee-woop" sound heard right before each cartoon irises out, as well as the "Acme brand" running gag. Although only active for a decade, Clampett left a huge impact behind on the 'Looney Tunes' franchise. His cartoons are renowned for their high level of energy, intensity and wackiness. He allowed his crew to draw off model and distort characters if it suited a certain emotion or gag. This makes the animation in his work both fluid as well as bizarre. Later in his career, Clampett made the popular TV puppet show 'Time for Beany' (1949-1955), which he later adapted into an animated spin-off: 'Beany and Cecil' (1962). His off-the-wall comedy, experimental nature, boundless creativity and sneaky jokes still influence modern-day cartoonists and animators.

Early life and career

Robert Emerson Clampett was born in 1913 in San Diego, California as a child of Irish immigrants. His family moved to Hollywood when he was still a boy. Their next-door neighbors happened to be Charlie Chaplin and his brother Syd. Naturally, Clampett was a huge fan of Chaplin and other Hollywood comedians, such as Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd and, years later, Laurel & Hardy and The Marx Brothers. In animation, his favorites were Winsor McCay, the 'Felix the Cat' cartoons by Otto Messmer & Pat Sullivan, Max Fleischer's 'Koko the Clown' and 'Betty Boop', and later Walt Disney. Clampett even once asked a film projectionist whether he was allowed to study a piece of 'Felix the Cat' film at home. Other graphic influences were Milt Gross, George Lichty and Bill Holman.

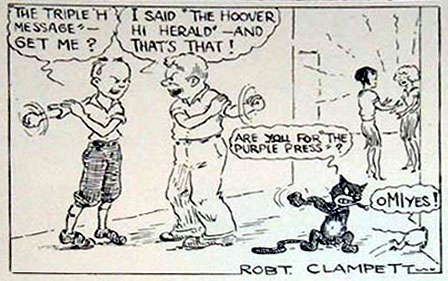

Comic strip drawn by "Robert Clampett" at age 12, and published in The Junior Times on 16 May 1926.

Early (comics) career

From an early age, Clampett showed talent for puppetry and drawing. As a student at Theodore Roosevelt Junior High School, he published comics and cartoons in their school newspaper, The Junior Times. One of his series, 'The Innocent Pussy', featured a black alley cat obviously inspired by 'Felix the Cat'. His other comic strip, 'Teddy the Roosevelt Bear', proved so popular that even after his graduation other students still continued it for years. At age 12, Clampett won a drawing contest, organized by the Los Angeles Times, a newspaper owned by legendary tycoon William Randolph Hearst. It published his comic strip about the aforementioned cat in the Sunday color section, The Junior Times. The teenager was additionally allowed to visit the paper's comic strip department, as well as its sister paper The Los Angeles Examiner. Here Clampett met professional cartoonists like Robert Day, Charles Philippi and Webb Smith (the latter two later became Disney animators). The teenager was allowed to work in this studio during school holidays. He was also offered a contract to become a cartoonist for both papers as soon as he finished high school. Clampett studied at Otis Art Institute, all lessons paid from Hearst's own pocket.

Encouraged, Clampett continued his studies at Harvard High School and Hoover High School in Glendale, where he was sports editor and columnist for their school papers. He also drew cartoons for the year books. Yet in 1931, only a few months before he would graduate, his father ran into financial troubles. The student broke off his studies and took a job at his aunt's doll factory. Inspired by the global success of Walt Disney's Mickey Mouse, Clampett suggested producing a series of dolls based on Mickey. He and his aunt took a prototype to the Walt Disney company and met Walt and his brother Roy. Disney greenlighted the project and the 'Mickey' dolls became an enduring merchandising hit. Clampett tried to apply for a job as animator while he was at it, but at that moment Disney had no need for extra people.

From Clampett's comic for his yearbook.

Warner Brothers

Still intent on becoming an animator, Clampett went to another cartoon studio. Warner Brothers had just set up their own animation department, headed by Leon Schlesinger. Clampett had met him before in 1923, when Schlesinger was still head of the Pacific Title and Art Studio. At the time, he'd ordered some printed titles for an amateur film. Eight years later, Schlesinger still remembered the teenager and instantly hired him. The 17-year old joined Friz Freleng's unit, where his drawing talent and creativity helped him move up the ladder. In 1935, Schlesinger held a contest among his employees to come up with the best script. The winner would see his story adapted into a short. Clampett won and Freleng directed his story as 'My Green Fedora' (1935).

In 1936, many new talents joined Warners, among them composer Carl Stalling, voice actor Mel Blanc and animators Chuck Jones and Tex Avery. Avery had a sarcastic and absurd sense of comedy. Under his lead, Warners gradually quit imitating Disney and did more of their own thing. The sentimentality of a typical Disney cartoon was brutally twisted with outrageous sarcastic jokes, absurd gags, sexual innuendo and violent punchlines. Avery loved taking advantage of the medium by throwing in physically impossible gags and exaggerating the cartooniness. His characters are completely aware they are in a cartoon. They address the audience or show the artificiality of the very short they appear in. His cartoons also nodded to popular radio shows, advertisements, films and news events. This helped the Looney Tunes become extraordinarily popular with teenagers as well as adults. Avery's spirit inspired many fellow directors: Chuck Jones, Friz Freleng, Frank Tashlin, Bob McKimson, Arthur Davis, Norm McCabe and, of course, Clampett.

Between 1936 and 1937, Bob Clampett worked in Avery's unit. While Avery was timid, Clampett was very extraverted. But they shared the same tremendous sense of comedy, imagination and experimental spirit. Both were willing to take risks to put their vision on the screen. Avery had already given Friz Freleng's character Porky Pig a funnier personality. In 1937, he introduced a far zanier star: Daffy Duck, who debuted in Avery's short 'Porky's Duck Hunt' (1937). The insane duck constantly tricked Porky and did all kinds of impossible things, like jumping up and down on top of his head, while yelling "Woo Hoo!". This was an idea of Clampett, while the catchphrase itself was borrowed from comedian Hugh Herbert. Daffy's jumps soon became one of his trademarks. Another enduring gag by Clampett was the "beee-woop" sound effect heard at the end of each cartoon. He voiced it himself. Clampett additionally created the animated sequence in the live-action film 'When's Your Birthday?' (1936), starring Joe E. Brown.

Art for the aborted 'John Carter of Mars' project. The drawing appeared on the cover of Jim Steranko's Mediascene magazine #21 in 1976.

John Carter of Mars

Between 1936 and 1937, Clampett worked on an animated film series based on Edgar Rice Burroughs' popular science fiction novels 'John Carter of Mars'. He wanted to market it to an adult audience and therefore used a more realistic and dramatic animation style. Burroughs and his son John Coleman liked the idea, but suggested MGM's cartoon studio rather than Warners, because they had connections there. However, the test footage failed to impress MGM's sales distributors. They were confident that people in the American Midwest wouldn't like science fiction and wanted to appeal to the entire country. Instead, they suggested an animated series based on Burroughs' more famous literary creation 'Tarzan'. The jungle hero had already proven to be a cash cow franchise both in Hollywood live-action movies, as well as the newspaper strip by Hal Foster and Burne Hogarth. The executives additionally wanted to keep everything child-oriented. Burroughs and Clampett instantly rejected this alternative and thus 'John Carter' was stranded. In hindsight it seems ironic that producers feared that audiences wouldn't like science fiction, since the 'Flash Gordon' film serial based on Alex Raymond's SF comic later became a major success, even in the American Midwest and South. And in 1941 the Paramount animated series 'Superman', based on Jerry Siegel & Joe Shuster's comic series, did extraordinarily well despite its realistic and serious tone. The same year, John Coleman Burroughs adapted 'John Carter' into a newspaper comic strip, which also caught on effortlessly.

Director

After his 'John Carter' project was axed, Clampett seriously considered leaving Warners. Schlesinger convinced him to stay and offered him his own unit, with complete creative control. Among the people once employed in Clampett's unit were Fred Abranz, Art Babbitt, Warren Batcheler, Jack Bradbury, Bob Cannon, John N. Carey, Don Christensen, Shamus Culhane, Basil Davidovich, Cal Dalton, Arthur Davis, Izzy Ellis, Manny Gould, Lucifer Guarnier, Gene Hazelton, Chuck Jones, Tom Massey, Norm McCabe, Bob McKimson, Chuck McKimson, Tom McKimson, Bill Melendez, Phil Monroe, Vivie Risto, Virgil Ross, Rod Scribner and Sidney Sutherland.

At first, Clampett co-directed with Ub Iwerks, Disney's former right hand, but after two Porky Pig cartoons, 'Porky and Gabby' (1937) and 'Porky's Super Service' (1937), Iwerks left again. Clampett co-directed four cartoons with Chuck Jones: 'Get Rich Quick Porky' (1937), 'Rover's Rival' (1937), 'Porky's Hero Agency' (1937) and 'Porky's Poppa' (1938), before Jones got his own director's unit. From that moment on, Clampett was the sole director of all his cartoons. Only in 1940, when he fell ill for a while, Norm McCabe completed direction for two unfinished cartoons 'The Timid Toreador' (1940) and 'Porky's Snooze Reel' (1940), and received co-credit for them too. Clampett also directed an incredibly short 'Porky Pig' cartoon in which the pig hits his thumb with a hammer and says "Son of a bitch!". This intentional blooper was made for 'Breakdowns of 1938' (1938), a compilation film of real bloopers which occurred on the Warner Brothers film set that year. 'Breakdowns of 1938' wasn't intended for public viewing, but for a private party for Warners employees. More than 60 years later, the cartoon gained infamy in the Internet era. When Tex Avery left Warners for MGM in 1942, Clampett completed a couple of storyboards he left behind and turned them into five completed shorts: 'The Bug Parade' (1941), 'The Cagey Canary' (1941), 'Wabbit Twouble' (1941), 'Aloha Hooey' (1942) and 'Crazy Cruise' (1942).

Still from: 'Porky in Wackyland'.

The early Clampett cartoons already show some memorable wacky scenes, such as Porky's car in 'Porky's Badtime Story' (1937) driving through a garage and pulling it inside out. But it took until 'Porky in Wackyland' (1938) before he created his first masterpiece. The plot brings Porky to a strange country where he hopes to find "the last living example of the rare Do-Do Bird". The Do-Do Bird was obviously inspired by Daffy Duck, manipulating reality and fooling Porky time and time again. Yet Clampett actually topped Avery in madness. All scenes are highly illogical. The backgrounds were leftovers from Clampett's aborted 'John Carter of Mars' project, but also inspired by Salvador Dalí's paintings. It all made up for the most surreal Looney Tunes cartoon at that point. The original short was made in black-and-white, but Friz Freleng later released a colorized version with only a few details changed: 'Dough for the Do-Do' (1949). Tex Avery later plagiarized Clampett's plot for his MGM cartoon 'Half-Pint Pygmy' (1948), while the idea of a surreal location was imitated in his cartoon 'The Cat That Hated People' (1948). At Terrytoons, Paul Terry plagiarized 'Porky in Wackyland' as 'Dingbat Land' (1949).

Napoleon and Uncle Elby

In 1938, Clampett and fellow animator Al Kendig opened a puppet studio. They developed a new, more sophisticated process for making stop-motion puppet films and considered adapting Clifford McBride's comic strip 'Napoleon and Uncle Elby' to the big screen. Their plans were thwarted by Schlesinger, who felt that their animated cartoons already preoccupied most of their work and his money.

Acme

In 1940, Clampett directed 'The Sour Puss' (1940), a Porky Pig cartoon notable for being the first to feature the fictional company Acme. Companies using this brand name had existed since the late 19th century and chose the word mostly because it meant "the best" and started with the first letter of the alphabet, making it handy to find back in telephone guides and product catalogs. In the Looney Tunes cartoons, of course, the products constantly fail or backfire. Yet the brand was already in vogue in Hollywood comedy films like Buster Keaton's 'Neighbors' (1920) and Harold Lloyd's 'Grandma's Boy' (1922), making Acme not an entirely original Looney Tunes invention. Nevertheless, it later became one of the franchise's trademark jokes, which soon popped up in cartoons by other animated studios, until it became an overused joke in English-language comedy. As a tribute, the man who produces cartoon props in the film 'Who Framed Roger Rabbit?' (1988) is named Raoul Acme.

Bugs Bunny

Tex Avery 's 'A Wild Hare' (1940) marked the debut of the brainless hunter Elmer Fudd and the wisecracking rabbit Bugs Bunny. Bugs instantly became Looney Tunes' major star and Clampett totally identified with his mischievous personality. Under his direction the rabbit became a gleeful, even quite nasty prankster. 'Hare Ribbin'' (1944) originally ended with Bugs shoving a gun inside a dog's mouth and killing him! Censors felt this way way too macabre and thus the scene was replaced with a different ending in which the dog pulls out a gun himself and commits suicide. In 'The Old Grey Hare' (1944), Bugs buries Elmer alive while laughing demonically! Even in his grave, he won't leave him alone and hands him a bomb, which explodes over the end credits.

Clampett's take on Bugs is additionally interesting because he tried to avoid the formula where the character is practically invincible. Tex Avery once had Bugs lose from a tortoise in 'Tortoise Beats Hare' (1941). Clampett directed a sequel to this cartoon, 'Tortoise Wins By A Hare' (1943) in which the rabbit tries a rematch and loses again. In 'Falling Hare' (1943), the undefeatable rodent is outsmarted by a gremlin. Both cartoons are notable because Bugs gets uncharacteristically angry and frustrated. However, audiences didn't react well to these cartoons, since they preferred to see Bugs as a winner who is always in control. Only only cartoon had him lose again since, namely Chuck Jones' 'Rabbit Rampage' (1955) (in Friz Freleng 'Rabbit Transit' (1947), Bugs defeats Cecil Turtle in a race, but still ends up on the receiving end of the punchline when the police arrests him for violating the speeding limit.)

Clampett also imagined how Bugs and Elmer might've looked as babies and old people in 'The Old Grey Hare' (1944). In 'The Big Snooze' (1946), Elmer terminates his contract with Bugs, because he is fed up that he can never catch him.

Style

Together with Tex Avery and Chuck Jones, Clampett was arguably the most innovative Looney Tunes director. Several of his Warners shorts are still classics: 'Porky in Wackyland' (1938), 'Wabbit Twouble' (1941), the Dr. Seuss adaptation 'Horton Hatches the Egg' (1942), 'The Wacky Wabbit' (1942), 'Bugs Bunny Gets the Boid' (1942), 'The Hep Cat' (1942), 'A Tale Of Two Kitties' (1942), 'Coal Black and de Sebben Dwarfs' (1943), 'The Wise Quacking Duck' (1943), 'Tin Pan Alley Cats' (1943), 'A Corny Concerto' (1943), 'Falling Hare' (1943), 'What's Cookin' Doc?' (1944), 'Russian Rhapsody' (1944), 'The Old Grey Hare' (1944), 'Draftee Daffy' (1945), 'Book Revue' (1946), 'Baby Bottleneck' (1946), 'Kitty Kornered' (1946), 'The Great Piggy Bank Robbery' (1946) and 'The Big Snooze' (1946).

From: 'Book Revue'. Here Daffy Duck imitates singer and comedian Danny Kaye's performances in the film 'Up in Arms' (1944).

Clampett developed wacky and energetic shorts in which characters experience the most intense emotions. They often twist their faces and limbs in the most exaggerated poses. In 'Porky in Egypt' (1938), a camel loses his mind because of the desert heat. The dog in 'Porky's Tire Trouble' (1939) swallows too much “rubberizing solution” and becomes completely rubbery as a result. Bugs gets so angry in 'Tortoise Wins By A Hare' (1943) that a funny close-up shows him baring out all his teeth. In 'Book Revue' (1946), Daffy transforms into a colossal eye when he notices the Big Bad Wolf, while Porky pulls Daffy's leg in 'Baby Bottleneck' (1946) with such strength that it stretches out like a long piece of string. While animators are usually forced to stay "on model" when they draw characters, Clampett allowed them to distort expressions to fit certain emotions. It gave his cartoons an unusual look, which makes them the easiest to identify each animator's personal touch. Some scenes look like unconnected extreme caricatures when you freeze frame them, like Daffy answering the phone in 'The Great Piggy Bank Robbery' (1946). But when one watches them at regular speed they all flow incredibly smoothly into each other. John Kricfalusi once pointed out that Clampett's characters have such vitality that they don't seem to follow direction.

As he'd proven with 'Porky in Wackyland', Clampett enjoyed putting familiar characters in weird contexts. In 'A Corny Concerto' (1943), Bugs is hunted down by Porky in a pantomime ballet sequence which parodies Disney's 'Fantasia' (1940). In fact, it was the first very first parody of this specific animated film ever. Daffy dreams he's Dick Tracy in 'The Great Piggy Bank Robbery' (1946) and meets a bunch of odd villains which surpass Chester Gould's own imaginative cronies. In 'The Big Snooze' (1946), Elmer Fudd is tormented by Bugs in a nightmare sequence. Sometimes Clampett would experiment with backgrounds too, like the odd abstract spots in certain scenes of 'Baby Bottleneck' (1946). Some gags are quite sneaky, even risqué. The pelican in 'Porky and Daffy' (1938) sweeps his beak across the floor in a manner that brings a scrotum into mind. Kricfalusi recalled watching this cartoon in the presence of Clampett in the early 1980s, who told them: "You fellas have dirty minds". Bugs crashes underneath a skeleton in 'The Wacky Wabbit' (1942) and for a few moments believes he's looking at his own remains. Daffy performs a striptease in 'The Wise Quacking Duck' (1943) (an idea plagiarized from Tex Avery's 'Cross-Country Detours', 1941) and acts as if his head was cut off by tucking it inside his body. In 'A Corny Concerto' (1943), Bugs pulls a bra over Porky and his watchdog's head. Yet no matter how wild his ideas went, each cartoon is still funny, very well-drawn and well-paced.

War-time propaganda cartoons

As the United States entered World War II in 1941, many Hollywood cartoon studios started producing propaganda shorts which ridiculed the Nazis and the Japanese army. Together with fellow directors Osmond Evans, Friz Freleng, Hugh Harman, Chuck Jones, Zack Schwartz and Frank Tashlin, Clampett also directed various military instruction cartoons only intended for private audiences of Allied Soldiers, namely the 'Private Snafu' cartoons and the 'Mr. Hook' short 'Tokyo Woes' (1945). Since they were exclusively intended for young soldiers, the cartoons were allowed to be a bit more risqué in their language and sexual allusions. Future celebrities who worked on these cartoons were P.D. Eastman, Munro Leaf, Dr. Seuss (writing) and Hank Ketcham (animation).

Clampett directed three war-time shorts for mainstream audiences as well. Coincidentally he made both the first Looney Tunes war-time cartoon, 'Any Bonds Today' (1942), as well as the final, 'Draftee Daffy' (1945). In 'Any Bonds Today?' (1942), Bugs, Elmer and Porky promote the sale of war bonds. At one point Bugs sings in blackface about 'Uncle Sammy', a scene nowadays widely misinterpreted ridiculing black people, but in reality it referred to the famous blackface singer Al Jolson, who had a hit song titled 'Mammy'. Clampett additionally directed 'Russian Rhapsody' (1944), in which Hitler decides to fly to Moscow on his own to bomb the city. However, during his flight he is attacked by gremlins sabotaging his plane. Funnily enough, in Clampett's earlier cartoon 'What's Cookin' Doc?' (1944), a newspaper headline hid a joke which came true a year later: 'Adolph Hitler commits suicide.' In 'Draftee Daffy' (1945), Daffy shows his patriotic spirit, but spends most of the cartoon avoiding the draft. The cartoon came out on 27 January 1945, five months before World War II was concluded in Europe.

Charlie Dog & Beaky Buzzard

Clampett created two minor Looney Tunes characters. In 'Porky's Pooch' (1941), the annoying Charlie Dog made his debut. Chuck Jones later reused this dog in combination with Porky Pig. 'Bugs Bunny Gets the Boid' (1942) marked the first appearance of Beaky Buzzard. The bashful vulture borrowed his dopey voice from Edgar Bergen's ventriloquist puppet Mortimer Snerd.

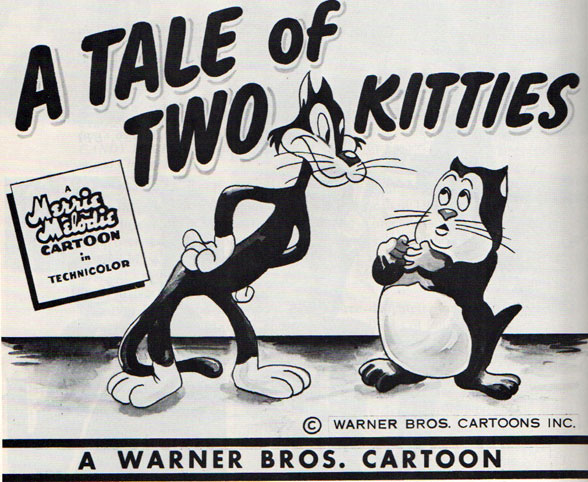

'A Tale of Two Kitties' (1942), directed by Bob Clampett, featured the introduction of Tweety. The two cats are caricatures of comedy duo Abbott & Costello.

Tweety

By far Clampett's most famous character is Tweety, the baby canary who debuted in 'A Tale of Two Kitties' (1942). He based him on comedian Red Skelton, who had a popular radio act titled the 'Mean Little Kid'. Just like this kid character Tweety was originally very malicious and sneaky, not unlike Clampett's version of Bugs. The bird also borrowed Skelton's baby voice, which mispronounced the letters "r" and "s", as demonstrated in Tweety's famous catchphrase: "I tawt I taw a puddy tat!" As such, he became another entry in a great Looney Tunes tradition of giving their main characters (like Porky, Daffy, Elmer Fudd and Bugs) speech impediments. The early Tweety lacked feathers, as one would expect from a baby bird. But Warner executives felt he looked "naked" and thus Tweety was redesigned with yellow feathers. As Clampett once said: "Nobody ever noticed that Porky Pig never wore pants." Clampett used Tweety in two more cartoons, 'Birdy and the Beast' (1944) and 'The Gruesome Twosome' (1945), before Friz Freleng paired the little canary with his own character, Sylvester the cat, in 'Tweetie Pie' (1947). The cartoon won the Academy Award for Best Animated Short, whereupon 'Tweety & Sylvester' became Freleng's signature series. The bird became more of an innocent bystander, while Sylvester basically defeated himself, much like Chuck Jones' Wile E. Coyote did in 'The Road Runner' cartoons.

Leaving Warners

In 1944, Warners' animation producer Leon Schlesinger retired, which left Clampett without his maecenas. His successor was Eddie Selzer, a very pragmatic, conventional and utterly humorless man. He wasn't fond of innovation and felt Clampett's cartoons were too eccentric, especially compared with the other directors in the studio. By May 1945, arguments had risen to such a degree that Clampett left Warners. It has never been resolved whether he was fired or quit on his terms. Either way, his departure was quite abrupt. Several cartoons under his direction who were still in pre-production at that time were finished and released in the months that followed. Some still came out even a year later. His final cartoon, 'The Big Snooze' (1946), was released without credit. Interestingly enough, it features a storyline where Elmer Fudd also decides to quit his contract.

Four planned pictures by Clampett were completed by Arthur Davis ('Bacall to Arms', 'The Goofy Gophers', [1947]), Bob McKimson ('The Birth of a Notion', [1947]) and Friz Freleng ('Tweetie Pie', [1947]). Freleng also remade and colorized two old Clampett cartoons: 'Scalp Trouble' (1939) as 'Slightly Daffy' (1944) and 'Porky in Wackyland' (1938) as 'Dough for the Do-Do' (1949). Originally, Arthur Davis took over Clampett's unit, but Selzer just disbanded this unit altogether, making Davis an animator again.

The Goofy Gophers

Clampett's final enduring Looney Tunes creations were two overly polite gophers, nicknamed 'The Goofy Gophers'. Debuting in 'The Goofy Gophers' (1947), the rodents have a tendency to let each other "go first", directly based on the mannerisms of Frederick Burr Opper's comic characters 'Alphonse and Gaston'. There is an additional strong possibility that The Goofy Gophers were inspired by Disney's chipmunks Chip 'n' Dale. The Goofy Gophers were later reused by other Looney Tunes directors, namely Arthur Davis, Friz Freleng and Bob McKimson.

Screen Gems

In 1946, Clampett joined Screen Gems, the cartoon department of Columbia Pictures, where he directed one animated short, 'It's a Grand Old Nag' (1946), before leaving the animation industry at the height of his success.

Dell Publishing published five Beany and Cecil books from 1962, with art by Willie Ito, among other artists.

Time for Beany/ Beany and Cecil

In 1949, Clampett moved into television, where he developed the puppet show 'Time for Beany' (1949-1955). The series centers around a young boy, Beany, his uncle Captain Huff'n'puff and Beany's friend Cecil, who is a green sea serpent. The puppets were designed by Maurice Seiderman, while Clampett, Daws Butler and Stan Freberg operated them and did the voices. In 1952 and 1953, Butler and Freberg left, whereupon Jim MacGeorge and Irv Shoemaker became new puppeteers. Although 'Time for Beany' was a children's show, its satirical tone also appealed to adults. The program won celebrity fans like Groucho Marx and Albert Einstein, who reportedly once left a scientific meeting early just to catch 'Time for Beany' on television. Rock musician Frank Zappa also had fond memories of watching the show as a child. 'Time for Beany' additionally inspired the puppets in the cult TV series 'Mystery Science Theater 3000' (1988-1999). Between 1951 and 1954, the puppet show was adapted in a comic book series by Dell Publishing, drawn by Jack Bradbury, Don R. Christensen and Willie Ito.

In 1962, Clampett made an animated version of 'Time for Beany', titled 'Beany and Cecil'. One of the animators who worked on it was Tony Sgroi. Yet the series only lasted one season and didn't feature the original actors. Censors rejected so much footage that the series fell behind schedule and went over budget. In a lawsuit, Clampett lost the rights for 16 years. Mattel refused to pay merchandising royalties and Clampett couldn't afford another trial. All he had were some ASCAP music royalties, since he also wrote music for his shows. For years, Clampett suffered from stress and once had to be hospitalized because of a serious illness. Only in 1978 did lawyer Bert Fields manage to negotiate a settlement, which helped him get the rights back. In 1988, John Kricfalusi tried a reboot, 'The New Adventures of Beany & Cecil', but bad ratings and reviews forced it into early cancellation after only five episodes.

Controversy

Clampett basically retired in 1962. Like most animators he suffered from the fact that general audiences only knew Walt Disney's name. It didn't help that post-World War II Warners cartoons received more TV airplay than older cartoons. The studio even removed the opening credits of many cartoons and replaced them with a picture of a blue ribbon, making it more difficult to identify individual animators. As such, Clampett's 'Looney Tunes' faded in obscurity for a few decades, only popping up on some TV stations now and then. Apart from Tweety, he didn't have any major characters to his name that people were familiar with. The veteran director gained more press attention through an interview conducted by Michael Barrier in issue #12 (Fall 1970) of Funnyworld. Clampett went into the lecture circuit at animation festivals and college campuses.

In 1975, Clampett directed a documentary/anthology film, 'Bugs Bunny Superstar' (1975), which was the first movie to address the history of Warner Brothers' animation department. Orson Welles provided narration, while Clampett, Friz Freleng and Tex Avery were interviewed. The picture featured eight complete classic cartoons, one by Avery, one by Bob McKimson, two by Chuck Jones, two by Friz Freleng and three by himself. However, the documentary gained controversy because Clampett took credit for a lot of things disputed by his former colleagues. The most contested claim was that he was the creator of Bugs Bunny and Porky Pig. Tex Avery, voice actor Mel Blanc and especially Chuck Jones weren't amused. Within the same week of its premier, Jones typed down all of Clampett's incorrect claims and let Avery write down his thoughts on the matter. Avery agreed that the majority of what Clampett had said was false and explained why. Jones then copied this document and sent it as a protest letter to Michael Barrier. He also made copies which he handed out to fans whenever he could. Jones' anger went so far that he made his own 'Looney Tunes' documentary four years later, 'The Bugs Bunny / Road Runner Movie' (1979). The film didn't feature any cartoons by Clampett, nor acknowledged his name. Even in Jones' autobiography 'Chuck Amuck' (1989), Clampett is almost absent. Mel Blanc mentions Clampett in his own autobiography, but ranked him as the worst director he had to work with.

With the passing of time, Clampett's negative press has largely been dissolved. People who knew the animation legend personally acknowledged that he was very self-assured, which, to some, could easily come across as self-centered. They also pointed out that many animators and other Looney Tunes employees, even Jones and Mel Blanc, often took credit for ideas and characters they didn't create. Several made their own contributions more important to receive more media attention. In some cases, these practices weren't even mean-spirited. Few interviews, especially in mainstream media, rarely left enough time to talk in depth. As a result, many anecdotes were simplified, leaving out many details, nuances and colleagues. Journalists, critics and audiences often misinterpreted info by assuming one person "made" certain cartoons or characters from scratch, instead of the more complex reality that they were developed over time by several different people. The dispute who "created" Bugs Bunny is hardly the only example in animation history. It's still debated whether Pat Sullivan or Otto Messmer "invented" Felix the Cat, and for years Ub Iwerks' creation of Mickey Mouse was completely or mostly attributed to Disney.

Not all of Clampett's colleagues were negative about him either. Frank Tashlin and Friz Freleng, for instance, didn't hold grudges, though Freleng wasn't too pleased when Clampett took credit for the first model sheet of Porky. Tex Avery, despite signing Jones' letter of complaint, later distanced himself again from the document. He still stood behind his statements, but didn't want to stay angry with Clampett, who never badmouthed his colleagues in public. Many historians agree that a certain degree of jealousy on behalf of Jones should also be taken in account. He started off as Clampett's co-director, but the two were polar opposites in terms of personality. Clampett was not only confident, but genuinely funny and experimental from the start. Jones took a few years longer to find and establish his own personal style. After Clampett left Warners, Jones and Freleng suggested Bob McKimson as his successor at Warners. McKimson was modest and not much of an innovator. Freleng later revealed that Jones supported McKimson becoming the new director, because he wouldn't be a creative threat to him.

Some Clampett fans have criticized Jones for toning down the wild style and personalities of the Looney Tunes series after their hero's departure. Jones felt Bugs and Daffy were "too zany". He gradually reduced the amount of madcap chases in favor of more verbal comedy. Bugs, who'd become too much of a bully during the war period, now became calmer and only attacked others out of self defense. Daffy changed from a crazy bird into an eternal loser. The duck now became vain, egotistical and jealous, but without losing audience sympathy. Yet in Jones' defense, most Hollywood cartoon studios after World War II gradually toned down the speed and zaniness. Audience's tastes were changing, as well as budgets. So it was rather a change of the times than a deliberate act of revenge towards Clampett. And even in his infamous letter of complaint about Clampett, Jones could still acknowledge that "Clampett was a good director and made some fine, funny pictures."

Still from: 'The Great Piggy Bank Robbery'.

Recognition

Throughout his career, Clampett was never nominated for an Academy Award. His cartoon 'Tin Pan Alley Cats' (1943) was buried as a time capsule by the U.S. Library of Congress in Washington as an "important art work for future generations to discover." 'Time for Beany' won the Prime Time Emmy Award for Best Children's Program three times, in 1950, 1951 and 1953. Clampett did win an Inkpot Award (1974) and a posthumous Winsor McCay Award (1988). In 2000, 'Porky in Wackyland' was added to the United States National Film Registry for its "cultural, historical and aesthetical significance."

Death, legacy and influence

Clampett passed away in 1984 in Detroit, Michigan, from a heart attack, shortly before his 71st birthday. Apart from bad publicity, he didn't live long enough to enjoy the same praise and awards the longer-living directors Chuck Jones and Friz Freleng received, which made him less of a household name in comparison. His most vocal promoter was John Kricfalusi, who met the veteran in old age and considers him both his mentor as well as biggest influence. He praised him frequently in interviews and offers analysis of Clampett's genius on his personal blog: John K. Stuff. He also provided audio commentary to Clampett's cartoons on official DVDs by Warner Brothers. Various elements in Kricfalusi's cartoons, especially 'Ren & Stimpy', are inspired by ideas and techniques from Clampett's cartoons. Stimpy's big bulbous nose, for instance, was taken from the Jimmy Durante-esque cat in 'A Gruesome Twosome'. The scene where a yak goes insane from starvation in the 'Ren & Stimpy' cartoon 'The Royal Canadian Kilted Yaksmen' (1993), pays homage to the hallucinating camel in 'Porky in Egypt'. The blotted backgrounds in some 'Ren & Stimpy' cartoons were inspired by 'Baby Bottleneck'. And just like Clampett, Kricfalusi let his animators draw scenes in their own styles, rather than slavishly stay on model.

Other artists influenced by Bob Clampett are Peter Bagge, Sally Cruikshank, Mike Fontanelli, Eric Goldberg, Stephen Hillenburg, Mike Judge and Bill Plympton. The 2019 'Looney Tunes' TV cartoons, directed and produced by Peter Browngardt and Alex Kirwan, are all done in a Clampettesque style. In Robert Zemeckis and Richard Williams' film 'Who Framed Roger Rabbit' (1988), Tweety and the Wackyland dodo are some of many classic cartoon characters featured in a cameo. Clampett gave himself several cameos in Looney Tunes cartoons. He's the tall man with glasses leaving the cartoon studio in Jack Kings animated short 'A Cartoonist's Nightmare' (1935), the hook-nosed man in red sweater and grey overall in Tex Avery's 'Page Miss Glory' (1936) and the human cannonball in Avery's 'Circus Today' (1940). In his own cartoons, he also gave himself a brief cameo during a fight sequence in 'Porky and Daffy' (1938), a wanted poster in 'The Lone Stranger and Porky' (1939), a Greek statue in a picket fence in 'Porky's Hero Agency' (1937) and the hook-nosed pink gremlin with red shoes in 'Russian Rhapsody' (1944).

His name lives on in the annual Bob Clampett Humanitarian Award.

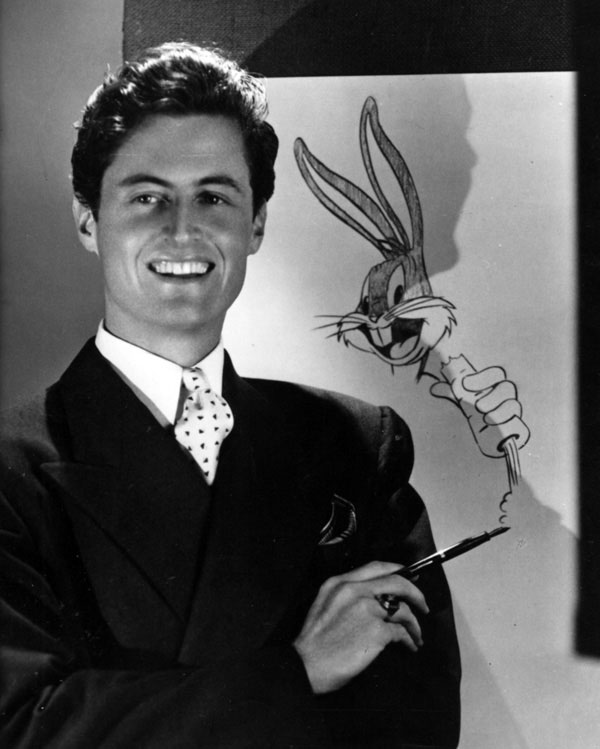

Bob Clampett.