Screen shot from a 'Bugs Bunny' cartoon.

Bob McKimson was an American animator and film director, most famous for his work for Warner Brothers. Together with Chuck Jones and Friz Freleng, he formed the core directors' team after World War II until the studio closed down in the 1960s. He directed various 'Looney Tunes' shorts starring Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck. McKimson created enduring characters like the loud-mouthed rooster Foghorn Leghorn (1946), the ultra-fast Mexican mouse Speedy Gonzales (1953) and the wild and monosyllabic Tasmanian Devil (1953). For a long while, his cartoons were downgraded as being more generic and less inspired than those of his fellow directors. Since the 1990s, his work has been revalued. McKimson is hailed for his beautiful artwork, which includes the definitive design of Bugs Bunny. Of all animators at Warners, he was most often put in charge of animating complicated sequences. Several of his shorts remain popular today.

Early life and career

Robert Porter McKimson Sr. was born in 1910 in Denver, Colorado. His father was a newspaper publisher and owned a weekly syndicated paper in Wray, Colorado, while his mother was an artist. He and his other brothers Tom and Chuck learned everything about drawing and publishing from them. Both Charles and Tom later become cartoonists and animators in their own right and often worked for the same companies. The family moved around between Colorado, L.A. and Texas until in 1926 finally moving to L.A. again. In 1928, Tom and Bob McKimson illustrated a children's book, 'Mouse Tales' (1928), written by their mother. After graduation from high school, Bob worked as a linotype operator in Hollywood, California.

Illustration from 'Mouse Tales' by Bob McKimson.

Animation career

In 1929, Tom McKimson became an assistant-animator at the Walt Disney Studios, thanks to an aunt who met Walt at a party and recommended Tom and Bob to him. Tom was assistant-animator to Norm Ferguson, while Bob joined up two weeks later and became assistant to Dick Lundy. The brothers only stayed there for a year, as their father lost his job, forcing them to support their entire family. Tom and Bob saw more financial benefit at the Romer Grey Studio, founded by the son of famous novelist Zane Grey (whose novel series 'King of the Royal Mounted' was adapted into a comic strip by scriptwriter Stephen Slesinger and drawn by Allen Dean and later Charles Flanders and Jim Gary). While the salary was good, Romer lost interest in his studio and spent most of the income on personal pleasures. Soon the company closed down without ever releasing anything.

Warner Brothers Animation

After leaving Romer Grey's scam, Bob and Tom joined Warner Brothers' brand new animation studio in 1931. Between 1937 and 1941 and again from 1946 until 1954, brother Chuck also found work there. While Tom and Chuck would eventually leave the company again, Bob McKimson stayed at Warners for the rest of his career. Together with Friz Freleng, he was the longest-remaining employee at Warners. But Freleng briefly worked for MGM between 1937 and 1939, while Bob McKimson's 30-year long career at Warners was uninterrupted: he was literally there almost from the start until the studio closed down in 1969. The McKimson Brothers earned a reputation for being skilled animators, able to pull off even the most complicated scenes. In 1935, Bob McKimson was already named head animator in Bob Clampett's unit. When Freleng left in 1937, he was offered the position of succeeding him as a director. However, McKimson felt he wasn't quite up for the task yet. Instead he suggested Chuck Jones, making him indirectly responsible for launching Jones' career as a director. Although Jones never knew about McKimson's gesture, he would coincidentally be responsible for suggesting McKimson's promotion to director about a decade later.

Bugs Bunny model sheet by Bob McKimson.

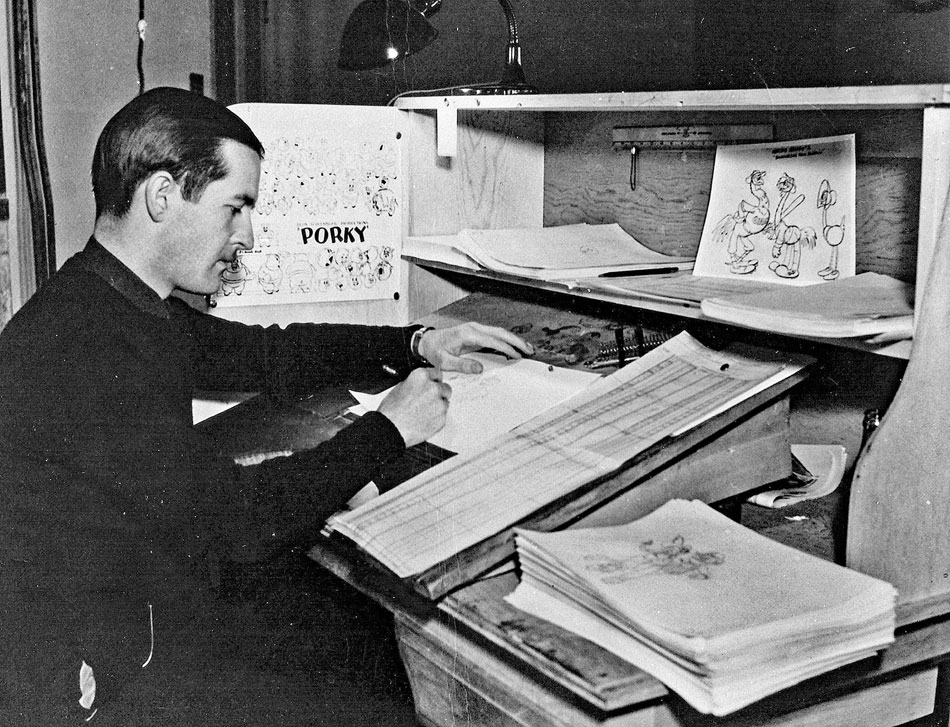

In the first half of the 1930s, Warner Brothers' cartoons merely imitated Disney and were therefore no success. From 1936 on, the studio headed into a different direction, thanks to newcomer Tex Avery. He directed far wilder, sarcastic, self-reflexive and above all funnier cartoons. All his fellow Warners directors, Bob Clampett, Frank Tashlin, Arthur Davis, Chuck Jones, Friz Freleng and McKimson, got caught by this new spirit. Avery made Freleng's pig character Porky (1936) funnier, while creating new characters like the crazy duck Daffy (1937) and the cunning rabbit Bugs Bunny (1940). During the late 1930s and early 1940s, McKimson mostly worked for Avery. He animated Porky in his debut picture 'I Haven't Got A Hat' (1936). When Bugs Hardaway made a prototypical design of the rabbit who'd eventually become Bugs Bunny, McKimson made him the tall and lean character most people recognize today. Originally, Avery only intended to use Bugs for one cartoon. In a 1971 interview conducted by Michael Barrier, McKimson said that he motivated Avery to make another cartoon with this wisecracking rabbit, because he enjoyed animating him so much. As such, 'Bugs Bunny' effectively became a series. When Avery left Warners for MGM in 1942, McKimson was put back in Bob Clampett's unit. McKimson and Rod Scribner also designed the first model sheets of Clampett's creation Tweety Bird (1942). The original Tweety had no feathers, since he was a baby bird. At the instance of their producers, they gave him yellow feathers, because he looked "naked." As Clampett often stated: "Nobody seemed aware that Porky never wore pants."

McKimson was in charge of checking all the other animators' individual drawings, which gave the Looney Tunes shorts a more unified look. Lay-out and complicated sequences were also given to them. Whenever realistic-looking characters had to be animated, like Uncle Sam in 'Old Glory' (1939), he was the go-to man. He was also the best choice for scenes which needed a believable dramatic build-up to a funny pay-off like the classic moment when Bugs fakes his own death in 'A Wild Hare' (1940), while Elmer comforts him. Some of the most complicated scenes in Looney Tunes cartoons were all animated by him. A prime example is the witch riding a bicycle in 'Coal Black And De Sebben Dwarfs' (1943), while all the bells on her bike swing back and forth synchronized with the melody on the soundtrack. Bob McKimson was renowned for his graceful and fluid animation. He could breathe life in a scene and had an eye for detail. The man was also a huge workaholic. He consistently completed twice the amount of required footage each day other animators did and every drawing still looked great. This remarkable talent was the result of a strange 1932 car accident, which ejected McKimson from his vehicle. Luckily, he survived, but a couple of nerves in his neck were pinched. When he left the hospital, he was suddenly able to work much quicker and more efficiently7 than before. Somehow the concussion had sharpened his visualization skills. His directors could just describe something to him or act out a scene and he would memorize it and recreate it on paper, without any preparation. McKimson never sketched things out and rarely erased lines, which explains why he was able to whip out so many quality drawings. During World War II, McKimson personally drew over 150 military insignias for the armed services depicting Bugs Bunny. He also drew a picture of Bugs for a woman who then donated 5.000 dollars worth of war bonds during a rally.

Lobby card for 'Rabbit's Kin' (1952), featuring the debut of Pete Puma.

Becoming a director

In 1943, McKimson directed his first cartoon, 'Return of Mr. Hook' (1943), but this was only a military propaganda short intended for soldiers, not general audiences. It wasn't until 1946, after main directors Frank Tashlin and Bob Clampett had left Warners, that he was finally promoted to director. Up to that point, the studio had four animation units, headed by Friz Freleng, Chuck Jones, Art Davis and Bob McKimson. However, their new producer, Eddie Selzer, felt that three was more than enough, which meant that somebody would have to be demoted. Freleng and Jones already had enough successful cartoons to their credit to keep their position. Therefore, they suggested keeping McKimson as a director and put Davis back in Freleng's unit. Historians have often wondered why Davis was rejected, since he made enough funny cartoons to at least be considered. On his personal blog, John Kricfalusi claimed that Freleng once explained to him what happened. For years, Bob Clampett had been one of Warners' funniest directors, while Chuck Jones was still looking for his own style. It irritated him that Clampett's work was much better received and that Warners producer Leon Schlesinger gave him far more creative freedom. Apart from that, Clampett also had a reputation for being a bit self conscious about his talent. When he left, Jones was so relieved that he deliberately wanted his successor to be more sympathetic and less of a creative threat, hence the choice for McKimson. In the aforementioned 1971 interview by Michael Barrier, McKimson revealed that he was well aware of the others' step-motherly treatment, but didn't really mind.

Among the artists who once worked in McKimson's unit were Fred Abranz, Warren Batcheler, Dick Bickenbach, Ted Bonnicksen, Pete Burness, John N. Carey, Phil DeLara, Izzy Ellis, Manny Gould, George Grandpré, Robert Gribboek, Ken Harris, Emery Hawkins, Volus Jones, Chuck McKimson, Tom McKimson, Bill Melendez, Tom Ray, Rod Scribner (for a brief period) and Bob Wickersham. Together with Chuck Jones, McKimson was one of the few directors who designed his own lay-outs. He was also the only director to design the promotion drawings for each of his new cartoons, which, at that time, were put on display inside the lobbies of film theaters.

Color model drawing of 'Foghorn Leghorn'.

Foghorn Leghorn

In 'Walky Talky Hawky' (1946), McKimson took a feisty little chicken hawk, Henery Hawk, originally created by Chuck Jones, and paired him with two brand new characters, Foghorn Leghorn and Barnyard Dog. Foghorn is a huge arrogant and talkative rooster. He often tries to lecture others, despite being quite dumb. Foghorn has an ongoing rivalry with a grumpy guard dog, Barnyard. They constantly try to trick each other, though often get the lid on their own noses. Foghorn's personality was based on the character Senator Claghorn from the radio show 'The Fred Allen Show' (1932-1949), played by Kenny Delmar. Delmar himself based Claghorn on an even older sheriff character from another radio sitcom, 'Blue Monday Jamboree' (1927-1935). Both spoke with a Texan accent, repeated sentences twice ("I say, I say son") and used proverbs and verbal comparisons. Various Looney Tunes characters were modeled after popular film and radio characters at the time, often down to their catchphrases. Voice actor Mel Blanc therefore saw no problem copying Claghorn's voice. The 'Foghorn Leghorn' cartoons developed into a series and would become McKimson's signature work.

Speedy Gonzales

In 1953, McKimson created another enduring character: the super-fast Mexican mouse Speedy Gonzales, who debuted in the cartoon 'Cat-Tails for Two' (1953). However, the original Speedy had buck teeth, a darker skin and no hat. McKimson based him on two Mexican brothers with whom he often played polo. The name 'Speedy Gonzales' referred to a well known dirty joke. The joke went as follows: a Mexican, Speedy Gonzales, is renowned for being an instant seducer of women and incredibly fast when having sex. One night, he knocks on a hotel room and wants to use the bathroom. The man lets him in, but keeps Speedy under the gun while holding one hand in front of his wife's vagina, out of fear he'll have sex with her. Everything goes well until the man sneezes, loses his grip, but immediately puts his hand back on her private parts. Suddenly, Gonzales appears to have gone and the man asks: "Where are you, little SOB?" Gonzales replies: "If you want me to leave, señor, you'll have to take your finger out of my asshole."

Friz Freleng redesigned McKimson's mouse by changing his fur, adding a different outfit and giving him a huge sombrero. In 1955, this redesigned version of Speedy Gonzales was relaunched and became an instant hit with viewers. He starred in his own long-running series, with Freleng's cat character Sylvester (from the 'Tweety & Sylvester' cartoons) cast as his nemesis. In 1959, Freleng also created the side character José "Slowpoke" Rodríguez, a mouse who is the exact opposite of Speedy, being his lethargic and slow cousin. Nevertheless, Slowpoke is bright enough to save himself from sticky situations.

Still from 'Dr. Devil and Mr. Hare'.

Tasmanian Devil

McKimson's final most recognizable character is the Tasmanian Devil (1954). Slightly based on the real-life Australian mammal with a huge appetite, the character rages over screens devouring everything in sight. Originally an adversary for Bugs in the cartoon 'Devil May Hare' (1954), producer Eddie Selzer utterly loathed him. He instructed McKimson to never use him again. Yet when Jack Warner, head of the studio, personally requested more cartoons with this ravenous carnivore, the Tasmanian Devil became a regular.

Minor characters

McKimson also created minor characters such as the kangaroo Hippety Hopper (1948), dim-witted villain Pete Puma (1952), stereotypical French-Canadian villain Blacque Jacque Shellacque (1959) and the rabbit gangster couple Bunny and Claude (1968), the latter based on the popularity of the film 'Bonnie and Clyde' (1967).

Reputation and criticism

Critics have often pigeonholed Bob McKimson as the weakest link at Warner Brothers' cartoon studio. Although he was a fine animator, his characters often have an odd, pudgy design, with half closed eyelids and short limbs. While Chuck Jones and Friz Freleng moved towards more downplayed acting in their cartoons, McKimson's characters are anything but subtle. Many constantly shout and push each other around. They tend to yell and gesticulate to get their point across. This works perfectly with extravagant characters like Foghorn Leghorn or the Tasmanian Devil, but less with others. Even the otherwise refined Bugs Bunny becomes a grouchy shouter under McKimson's direction. In general, McKimson wasn't preoccupied with innovation. Most of his cartoons feature generic, silly comedy situations. While all directors unavoidably make some less inspired cartoons, animation critic Charles Solomon observed that McKimson has more examples in this field than Jones or Freleng. McKimson also kept making wacky, flamboyant cartoons long after this style went out of vogue. Even when Jones and Freleng redefined Daffy Duck as a vain and mean loser, McKimson kept portraying the duck as a lunatic.

McKimson also directed four cartoons which directly parody popular radio and TV sitcoms of the time, like 'The Honeymooners' ('The Honey-mousers', 1956, 'Cheese It! The Cat', 1957, 'Mice Follies, 1960) and 'The Jack Benny Show' ('The Mouse That Jack Built', 1959). The Looney Tunes cartoons often referenced pop culture of the time, but rarely throughout the entire episode. The downside of these cartoons is that they rely heavily upon the source material. As the original TV series are mostly forgotten by younger audiences, they rank among the most dated shorts in the Looney Tunes catalog. Parody cartoons in itself weren't new, nor were celebrity voice actors. As early as 1932 the 'Betty Boop' cartoons 'I Heard' (1932), 'I'll Be Glad When You're Dead You Rascal You' (1932) and 'Minnie the Moocher' (1932) by Max Fleischer starred the voices of respective jazz legends Don Redman, Louis Armstrong and Cab Calloway. The Walt Disney company also brought in Cliff Edwards ('Pinocchio', 1940, 'Dumbo', 1941), Bing Crosby ('The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad', 1946), Basil Rathbone ('The Wind in the Willows, 1946) and Peggy Lee ('The Lady and the Tramp', 1955), to name a few. But 'The Mouse That Jack Built' marked the first time a celebrity actor voiced the same character he played on radio or TV. In that regard, McKimson's cartoons can be the considered the first examples of special guest voices based on TV stars in animation, long before Hanna-Barbera's 'The Flintstones' (1960-1966) and Matt Groening's 'The Simpsons' 1989- ) came about. Jack Benny was so pleased with his performance that he refused a salary but requested a print of 'The Mouse That Jack Built' instead. Jackie Gleason, on the other hand, didn't like McKimson's spoofs of 'The Honeymooners' and tried to prevent its premier. Yet when McKimson sent him a print of 'The Honey-Mousers' he withdrew his complaint.

Studio problems

From 1953 on, McKimson's unit suffered from problems beyond his own direction. During the early years, he could still rely on good scriptwriters and animators. He was also more willing to follow their suggestions, which often led to interesting cartoons like 'The Windblown Hare' (1949), in which Bugs helps the Big Bad Wolf catch the Three Little Pigs, and 'Rebel Rabbit' (1949), where Bugs becomes a psychopath who terrorizes the entire world. Unfortunately, good employees like Warren Foster or Rod Scribner were often brought back to Chuck Jones and Friz Freleng's units. Their replacements were usually people other directors didn't want to use any longer. Soon McKimson's unit became a dumping ground for unmotivated cynics, alcoholics, less talented artists and/or inexperienced newcomers. The situation grew worse in 1954 when Warners closed down its studio for a few months. At the time 3-D movies were very popular and Warners' producers were convinced that nobody would want to see normal pictures anymore. After a few months the fad predictably fizzled out and everybody returned to their units. However McKimson found out that few of his former employees came back! Not even his brother Chuck, who joined Dell Publishing instead to become an art director! As a result, McKimson was understaffed for a few months. He even made two new cartoons, 'The Hole Idea' (1954) and 'Dime to Retire' (1954), completely on his own. Both are done in black-and-white and feature a quite unusual style. Regarding the fact that they were basically one-man projects proved that McKimson was capable of being original even in the worst circumstances. In fact, other than Winsor McCay, Sally Cruikshank and Bill Plympton, there are few known examples of cartoons animated entirely by one person!

Recognition

Two cartoons directed by Bob McKimson were once nominated for an Academy Award, but both lost. The first one was 'Walky Talky Hawky' (1946), which lost to the 'Tom & Jerry' cartoon 'The Cat Concerto'. The second, 'Tabasco Road' (1957), lost the Oscar to the 'Tweety & Sylvester' cartoon 'Birds Anonymous', by McKimson's colleague Friz Freleng. In 1984, Bob McKimson posthumously received a Winsor McCay Award.

Final years and death

Eventually McKimson rebuilt his unit from scratch, but most of his personnel remained sub-par. As the 1950s progressed into the 1960s, budget cuts weakened the overall look and content of most of his work. By 1962, when most of Warners' cartoon staff left, McKimson stayed until the studio effectively closed down in 1963. He briefly joined UPA, directing some cartoons starring 'Mr. Magoo', before directing 'Pink Panther' cartoons at Friz Freleng's own cartoon studio: De Patie-Freleng. In 1967, Warners reopened their animation department and McKimson returned one year later. But it was nothing more than a death gasp. In 1969, Warners closed again, whereupon McKimson returned to DePatie-Freleng in 1972. Basically all his work from this era is generally regarded as forgettable.

In 1977, McKimson had lunch with Freleng and his business partner DePatie. He had just been informed by his doctor that he was in extremely good health and would probably live up to 100, just like his father. McKimson joked that he'd probably outlive all of his colleagues at Warners. In a tragic irony, he suffered a heart attack a few moments later and died on the spot. He was only 66.

Still from 'Hillbilly Hare', 1950.

Legacy and influence

Throughout his career McKimson was only interviewed once, by Michael Barrier in 1971. The quiet, modest man was too shy to go to fan meetings. He died just when classic animation received more serious attention and a huge resurgence in popularity. Since Chuck Jones and Friz Freleng outlived him by several decades, they received far more media attention and recognition. McKimson's cartoons were also unfairly compared with Jones, Freleng, Tex Avery, Bob Clampett and Frank Tashlin's work, rather than be judged on their own terms. However, by the 1990s, his reputation and notability increased. Looney Tunes fans acknowledge that McKimson was an exceptionally dynamic animator. His cartoons are vivid with movement. Compared with many of his colleagues, he kept working in the traditional, fully animated style, long after most other studios and directors had changed to a more minimalistic, budget-concerned style in the 1950s.

Some of the funniest Warners cartoons were directed by McKimson and still entertain audiences: 'Daffy Doodles' (1946), 'Walky Talky Hawky' (1946), 'Acrobatty Bunny' (1946), 'Birth of a Notion' (1947), 'Hop, Look and Listen' (1948), 'Hot Cross Bunny' (1948), 'The Foghorn Leghorn' (1948), 'Rebel Rabbit' (1949), 'The Windblown Hare' (1949), 'Hippety Hopper' (1949), 'Boobs in the Woods' (1950), 'What's Up Doc?' (1950), 'It's Hummer Time' (1950), 'Hillbilly Hare' (1950), 'Pop, I'm Pop' (1950), 'Hare We Go' (1951), 'Early to Bet' (1951), 'Rabbit's Kin' (1952), 'Of Rice and Hen' (1953), 'Little Boy Boo' (1954) and 'Tabasco Road' (1957).

Foghorn Leghorn, Speedy Gonzales and the Tasmanian Devil have legions of fans. Speedy Gonzales inspired no less than two songs. 'Speedy Gonzales' (1962) by Pat Boone was built around samples of the character's voice and became a Top 10 hit in the United States. The band The Astronauts performed 'Little Speedy Gonzales' as part of the soundtrack of 'Wild on the Beach' (1965). Musician Mojo Nixon once claimed that his personal "holy trinity of heroes" consisted of Elvis Presley, Otis Campbell and Foghorn Leghorn.

Foghorn Leghorn and Speedy Gonzales received cameos in Robert Zemeckis and Richard Williams' film 'Who Framed Roger Rabbit' (1988), among many other classic characters from the Golden Age of Animation. In 1991, the Tasmanian Devil experienced an increase in popularity thanks to his own animated TV series 'Taz-Mania' (1991-1995). Artists who drew comics with the Tasmanian Devil have been Fabio Bono. Speedy Gonzales, on the other hand, became more controversial in more politically correct eras. Fear of offending Hispanic people led to a temporary ban on television. But as it turned out, many Mexican and Hispanic people actually didn't feel offended by Speedy at all, since he is a generally nice, smart and heroic character who outwits everybody. As a result he made a spectacular comeback, appearing in the film 'Space Jam: A New Legacy' (2021). In 2017, Tony Bedard and Barry Kitson paired the Tasmanian Devil with William Moulton Marston's 'Wonder Woman' in the crossover comic book series 'Wonder Woman / Tasmanian Devil'. The character Scrappy-Doo in Hanna-Barbera's animated series 'Scooby-Doo' was inspired by McKimson's Henery Hawk.

John Kricfalusi has defended McKimson's work on many occasions. He has fond memories of watching 'Foghorn Leghorn' on TV with his dad, who otherwise disliked cartoons. In his opinion, McKimson's cartoons appealed to regular viewers, the average folks. On his blog, 'John K. Stuff', Kricfalusi observed that "all the characters in McKimson's cartoons are grumpy, middle-aged curmudgeons. It's a really funny world view that you see only in his cartoons. The main contrasts in the different characters' personalities was in how smart or how stupid the various curmudgeons were. (...) McKimson showed the world to be a hornet's nest of swindlers and wiseasses who go through life shouting, manhandling and pushing each other around - just like real life would be if we were unfettered by political correctness and insincere manners."

Books about Bob McKimson

For those interested in Bob McKimson's life and career, his son Bob McKimson Jr. published a biography about his famous father and his two brothers Tom McKimson and Charles McKimson named 'I Say, I Say... Son!' (Santa Monica Press, 2012). The foreword was written by longtime fan John Kricfalusi.