'America's Guardian Angel', a 'Wonder Woman' story in Sensation Comics #12 (December 1942).

William Moulton Marston was an American psychologist, generally miscredited as the sole inventor of the systolic blood pressure test, which laid the foundations for the polygraph and lie detector. In reality, this invention was made in collaboration with his first wife, Elizabeth Holloway. But Marston did undisputedly create the most iconic female superhero of all time: Wonder Woman (1941- ). During the final six years of his life, he developed her origin story and shaped her universe. He invented her uniform and trademark attributes, like her defensive bracelets, 'Lasso of Truth' and invisible plane. Marston also created several side characters in the franchise, such as her love interest Steve Trevor (1941), good friend Etta Candy (1942), and recurring villains Dr. Poison (1942) and Dr. Psycho (1943). Together with co-writers like Joye Hummel, and artist Harry G. Peter, Marston also wrote plotlines for the first six years of the series. 'Wonder Woman' became one of DC Comics' most popular superhero series, rising to the level of one of their "Big Three", alongside Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster's 'Superman' and Bob Kane and Bill Finger's 'Batman'. The character has become a feminist icon and was adapted in various media. Nevertheless, Marston's private life and personal psychology have cast a controversial shadow over the early years of his signature comic strip. He had a polyamorous relationship and regarded submissiveness as "empowering" to women. These themes also run in his stories, which have a questionable undercurrent of erotic bondage, role play and spanking. While this aspect of Wonder Woman has been contested and airbrushed from the series after Marston's death, it also ensured that Marston's life and work continue to fascinate audiences and comic historians.

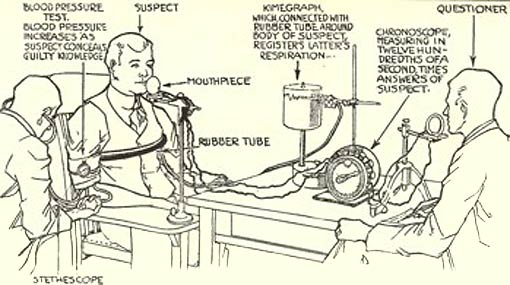

Drawing of Marston's "Original Harvard Experiment" (1915).

Early life and academic career

William Moulton Marston was born in 1893 in Cliftondale, Saugus, Massachusetts. He came from a privileged background and from an early age he was surrounded by strong, independent women like his mother and his unmarried aunts. Marston went to Harvard University, where he first studied law, but eventually became more interested in psychology. A brilliant student, he graduated with a B.A. (1915), L.L.B. (1918) and Ph.D (1921). During his university years, he met a woman who was in many ways his soulmate: Elizabeth Holloway. Holloway was an equally gifted academic and they married in 1915. She received her B.A in psychology at Mount Holyoke College (1915), followed by a L.L.B at the Boston University School of Law (1918) and an M.A at Radcliffe College (1921). Throughout her career, she indexed documents of Congressional meetings, worked as an editor for the Encyclopaedia Britannica and McCall's Magazine and frequently gave lectures at universities. Between 1933 and 1968 she was assistant-chief executive at Metropolitan Life Insurance. From 1921 on, Marston worked as a psychology professor at the American University in Washington D.C. and Tufts University in Medford, Massachusetts. Between 1929 and 1930 he was also briefly head of the Public Services department of Universal Studios.

The systolic blood pressure test

Marston is generally credited as the inventor of the systolic blood pressure test. In reality, it was his wife, Elizabeth Holloway, who came up with the original theory. While the couple studied blood pressure in university, she noticed that it rose whenever she was angry or excited. She made a connection between emotion and blood pressure, which led to their development of the systolic blood pressure test. Holloway allowed Marston to take all the credit for this invention, which led to his B.A. During the First World War, Marston became a second lieutenant and tried to sell the systolic blood pressure test to the U.S. Army to interrogate prisoners-of-war. However, his method wasn't considered reliable enough. In 1921, John Augustus Larson and Leonarde Keeler used the systolic blood pressure test to develop the polygraph, a predecessor to the modern-day lie detector.

Marston (seated) conducting a lie detector test. The woman on the left is Olive Byrne.

Feminism and bondage theories

Marston was a strong supporter of feminism in an era when women were still commonly regarded as second-class citizens. He defended the suffragette movement and women’s right to vote, while many of his male contemporaries were opposed to this idea. Another aspect that made him ahead of his time was his open discussion of sexuality. Many people in the early 20th century preferred to keep this topic private, especially in U.S. society, but Marston devoted various essays and lectures to the subject. However, his theories about sex, gender and feminism differed greatly from most other sexologists and feminists. In his opinion, men were aggressive by nature and prone to conflicts. Women, by comparison, were more pacifist, honest and diligent. This allowed them to work quicker, more efficiently and diplomatically. Marston felt that women were superior to men. Yet, at the same time, he also theorized they were submissive by nature and ought to behave accordingly. In a strange, seemingly contradictory line of thought, this submissiveness would allow women to “become empowered” and “one day rule the world, to the benefit of humanity.” Within this context, it is perhaps not surprising that Marston loved bondage. He wrote several essays about it.

Standing: Byrne Marston, Moulton (Pete) Marston and Olive Byrne Richard. Sitting: Marjorie Wilkes, Olive Ann Marston, William Moulton Marston, Donn Marston and Elizabeth Holloway Marston.

Polygamous family life

In 1919, while his wife Elizabeth Holloway was already pregnant, Marston met another woman close to his personal interests: Marjorie Huntley. Huntley was not only a suffragette, but being tied up during sexual role-play turned her on. They developed an extramarital affair and soon enough Marston told Elizabeth about the situation. Rather than ask for a divorce, he assured her that he didn’t want to leave her, but instead live together in a ménage à trois. After a six-hour walk to let it all sink in, Elizabeth accepted the proposal.

Yet in 1925, matters became even more complicated, when Marston met yet another woman of his dreams: Olive Byrne. Byrne was one of his younger female students. She was related to two famous suffragettes who both opened the first birth control clinic in the USA, namely her mother, Ethel Byrne, and aunt, Margaret Sanger. Byrne was into bondage and by all accounts a nymphomaniac. She surprised Marston by taking him to a kinky sorority party. Here female students made other students dress up as babies, while they had to carry out tasks, blindfolded and tied down. The experience later inspired the ‘Wonder Woman’ story 'Grown Down Land’ (issue 31, 1944). Soon Olive became Marston’s third wife. Marston had two children with Elizabeth, and another two with Olive. In 1935 Olive’s children were legally adopted by William and Elizabeth.

As unusual as the Marston’s family life was, the women are reported to have gotten along very well. They participated with their husband in a free love cult, nicknamed the “Love Unit”. Marston even wrote a 95-page manual on how they had to behave during their sexual role-plays. The women also divided their domestic tasks. Elizabeth concentrated on her academic career. Olive stayed home and took care of the household and the children. Occasionally she brought in some income too as a columnist for the magazine Family Circle. Ironically she usually wrote about “wholesome family homes”. Out of gratitude for her parenting, Elizabeth named a daughter after Olive. Even after Marston’s death, Elizabeth kept supporting Olive and her two children financially. Olive Byrne died in 1985 (some sources claim 1990). Elizabeth lived to become 100 years old and died in 1993.

Many historians have pointed out the irony that the inventor of the systolic blood pressure test, AKA “the lie detector”, built his private life on a lie to the outside world. Marston kept his polygamous relationship a secret to his children and other people. Officially, Olive was named his “sister-in-law, who worked as a housekeeper.” His children with Olive were “orphans, whose actual father had passed away before their birth.” Marston’s offspring only found out the truth in 1963, when they were already adults.

Early sketch of Wonder Woman, with notes by Marston (red) and Peter.

Damaged reputation

Although Marston was a respected professor earlier in his career, his reputation was tarnished on 1 December 1922, when he was indicted for federal business fraud. He had allegedly used mails and aiding in concealing assets from a trustee in bankruptcy. At the time he was treasurer and stockholder of the United Dress Goods, Inc., founded in 1920 and filed for bankruptcy in January 1922. Several creditors accused him of misrepresenting the financial condition of his firm, which allowed him to obtain considerable bills from them. On 19 February 1923, Marston was arrested by FBI agents, but by January 1924 the charges were dropped, thanks to efforts from lawyer and former fellow student Richard Hale. Still, it cost Marston the chairmanship of the psychology department at American University, his professorship and the directorship of the only psycho-legal research laboratory in the United States.

His controversial sex and gender theories didn’t endear Marston to fellow university graduates either. And while he tried to present his family life as “normal”, his polygamous relationship was an open secret to most people in his direct environment. Soon he was persona non grata in every university in the country. During the final decades of his life, he was reduced to living off his wives’ earnings. This ironically put him, a proponent of submissiveness of women, in a submissive position himself. Marston did occasionally hold lectures, but wasn’t allowed to actually do academic research or teach students.

Comic career

Throughout his career, Marston tried to promote his philosophies about sex and gender through more easy-reading literature. His first attempt was the novel 'Venus with Us’ (1932), but this wasn’t a success. The book is nevertheless important as Marston’s first attempt to fit his theories into a narrative. In 1940 and 1942 he was interviewed for The Family Circle in an article titled 'Don’t Laugh at the Comics’, written by his wife Olive under a pseudonym. In the article he argued that comics shouldn’t be dismissed as pure escapist pulp, but, on the contrary, had “great educational potential”. Max Gaines, publisher of National Periodicals and All-American Publications (nowadays DC Comics), read the article and was so impressed that he hired Marston as a consultant. Gaines’ company had just struck gold with their best-selling superhero comic series 'Superman’ (created by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster) and 'Batman’ (created by Bob Kane and Bill Finger). As they developed several other series in the same genre, they were very interested in gaining more prestige among demographics who usually didn’t read comics. Gaines was blissfully unaware that Marston was not the ideal person to increase their respectability, as he was no longer in demand as a professor and due to the scandals surrounding his personality seen as an academic disgrace. Gaines’ ignorance of Marston’s situation was lucky for comic history, in hindsight, as the world might otherwise never have heard from Wonder Woman.

The "birth" of Wonder Woman, from All Star Comics #8 (December 1941 - January 1942).

Wonder Woman

At National Periodicals, Marston pitched a superhero comic where the protagonist used love as a weapon, rather than violence. At the suggestion of his wife, Elizabeth Holloway, he made the character a woman. In the early 1940s, there were hardly any female comic characters in a starring role. France had Emile-Joseph Pinchon's 'Bécassine' (1905) and Jo Valle and André Vallet's 'L'Espiègle Lili' (1909), but they were unknown outside the francophone world. In the USA, the most enduring comic series about women were Gene Carr's 'Lady Bountiful' (1902-1929), Cliff Sterrett's 'Polly and Her Pals' (1912-1958), Abe Martin's 'Boots and Her Buddies' (1924-1959) and Chic Young's 'Blondie' (1930- ). Superhero comics were a particularly male universe, with women mostly being damsels in distress. Exceptions were 'Fantomah' (1940) by Fletcher Hanks, 'Black Widow (Claire Voyant)' (1940) by George Kapitan and Harry Sahle, 'Invisible Scarlet O'Neil' (1940-1956) by Russell Stamm, 'Nelvana of the Northern Lights' (1940) by Adrian Dingle and 'Miss Fury' by Tarpé Mills. Yet none of these early superheroines had a strong impact.

Marston therefore had enough room to invent his own ideal superheroine. To draw her adventures, he picked out Harry G. Peter, a veteran artist who was known for his pro suffragette cartoons. Peter designed a black-haired woman who wears a tiara, a red bustier, white belt, arm bracelets, golden boots and a dark skirt patterned after the American flag. Originally she was called "Suprema", but this was eventually changed into the snappier 'Wonder Woman'. Her physical features, personality and attributes were loosely based on Marston's own wives. Just like Elizabeth Holloway, Wonder Woman is strong, intelligent and liberated. Her looks were loosely based on his second wife Olive Byrne, down to her arm bracelets. Holloway also came up with Wonder Woman's catchphrases: "Suffering Sappho" - referring to the Greek lesbian poet Sappho - and "Great Hera!" - a nod to the Greek goddess of women Hera.

'Wonder Woman'. The cover of the first and second issue, 1941.

Marston developed an origin story and personal background for Wonder Woman, loosely inspired by ancient Greek mythology. Her real name, Diana, was inspired by the Greek goddess of hunt, Diana. Wonder Woman lives on a faraway island ruled by women, inspired by the Amazonians and modeled after Mount Olympus. The local queen Hippolyta sculpted her from clay. The gods blessed this creation with various gifts and powers, including a telepathic device named "mental radio". Her tribe worships Aphrodite, the ancient Greek goddess of love. Wonder Woman debuted in the eighth issue of All Star Comics (December 1941). In her first story, a U.S. intelligence officer, Steve Trevor, crashlands on her island. She is given the task to bring him back to his home country. Under the alias 'Diana Prince', Wonder Woman works as an army nurse and later an air force secretary. The first Wonder Woman story came out the same month when Japan attacked Pearl Harbour and plunged the U.S. into World War II. Many of the early stories reflect the real-life war period, with Wonder Woman fighting Nazis and Japanese soldiers, spies, saboteurs and other enemies.

While Wonder Woman is strong and intelligent, she originally relied a lot on gadgets. One of these is her "invisible plane", a transparent airplane flown to remain unnoticed by enemies. Since this vehicle looks somewhat silly, it is nowadays rarely used in the franchise. Far more prominent is her "Lasso of Truth". Whoever she ropes with it is forced to tell her the truth. The analogy with Marston's own invention, the lie detector, is obvious. He also snuck in other elements in line with his sex and gender theories. Wonder Woman's home island, where women rule, is unsubtly named 'Paradise Island'. Her bracelets can withstand energy beams and gunfire and are nicknamed the "bracelets of submission". Wonder Woman often fights regular villains, but also people who oppose female empowerment, like her major nemesis Doctor Psycho. Wonder Woman also motivates other women to stand up for themselves.

'Wonder Woman' daily comic strip.

Assistants

Marston had the creative freedom to do what he wanted with the character, even though his lack of experience in writing for comics occasionally led to some long-winded narratives. Originally, all stories were credited under the pseudonym "Charles Moulton", but when Wonder Woman received her own comic book line, he finally revealed he was her creator. In reality, the comic was more of a family product. Marston's wives and children occasionally came up with ideas. His second wife, Marjorie Huntley, and his daughter-in-law, Louise Marston, did lettering and inking. In fact, more women worked on it than men, including Helen Schepens (coloring) and Jim and Margaret Wroten (lettering). Joye Hummel, a student of Marston, ghost-wrote several storylines. From 1945 on, when his health declined, she de facto became the series' main writer until he passed away in 1947.

Wonder Woman in Sensation Comics #8 (August 1942).

Success

After only one month of publication, Wonder Woman sported the cover of the first issue of Sensation Comics (January 1942), and remained a regular feature in this title, as well as in the anthology title Comic Cavalcade. Six months later she received a series of her own. 'Wonder Woman' was a huge bestseller all throughout the 1940s. The comic book also had a back-up feature called 'Wonder Women of History'. Scripted by former tennis player Alice Marble, it told stories in comic form, about prominent women of history. In May 1944, Wonder Woman also received her own daily newspaper comic strip through King Features Syndicate, scripted by Marston and drawn by Harry G. Peter, but it lasted only less than a year.

Final years and death

William Moulton Marston lived long enough to see 'Wonder Woman' become a runaway success. But he could only enjoy it for six years, as his health declined from polio and skin cancer. In 1947, he passed away. Although his comic career was short-lived, Marston had the foresight of signing a financially lucrative contract with DC before his death. The company was contractually obliged to publish at least four issues of the series a year, or they would lose their rights. As a result, he was one of the few comic writers to get rich off his own creation and pass his wealth on to his surviving family members.

Wonder Woman after Marston's passing

After Marston's death in 1947, his wife Elizabeth wrote to DC Comics to succeed her husband as creative consultant. Instead, Robert Kanigher became the series' main writer, while Harry G. Peter remained the illustrator until 1958. From issue #98 (May 1958) on, Ross Andru and Mike Esposito took over drawing duties. Wonder Woman's groundbreaking female powers and embarrassing bondage themes were replaced in favor of more conventional superhero stories. She also received a teenage spin-off series, 'Wonder Girl' (1958), and junior spin-off 'Wonder Tot' (1961-1965). In 1968, a new artistic team was established, with Denny O'Neil as scriptwriter and Mike Sekowsky providing illustration work. They created a new set-up, in which Wonder Woman gives up her powers to become an ordinary woman. She opens a boutique and studies martial arts under a Buddhist monk named I Ching. Cashing in on the success of spy and kung fu media, Wonder Woman became a secret agent with the ability to dropkick anyone. In a controversial plot development, her love interest Steve Trevor was killed off. Between the late 1960s and early 1970s, 'Wonder Woman' aimlessly wandered around, with different scriptwriters and artists taking turns. Science fiction novelist Samuel R. Delany, famous for his novel 'Babel-17' (1966), wrote two issues, namely #202-203 (October/December 1972).

'Wonder Woman' #7 (Winter 1943).

In 1973, Wonder Woman returned to her roots, mostly with celebrity support from real-life feminist Gloria Steinem. She not only became a beacon of feminism again, but was firmly established as one of the most important superheroes, alongside DC's Superman and Batman. Wonder Woman also became an active member of the Justice League, in which DC's superheroes team up to fight crime. Writers like Robert Kanigher, Len Wein, Cary Bates, Ellio S. Maggin, Martin Pasko, Jack C. Harris and David Michelinie penned the most 'Wonder Woman' stories, while artists like Curt Swan, Tex Blaisdell, Irv Novick, Frank Giacoia, John Rosenberger, Vince Colletta, Dick Dillin, Kurt Schaffenberger, Dick Giordano and José Delbo visualized the narratives. The 1980s kicked off with the return of Steve Trevor (issue #271, September 1980). Two years later, Roy Thomas and Gene Colan gave Wonder Woman a makeover by replacing the eagle on her chest with a "WW", designed by Milton Glaser. During this decade, female scriptwriters like Dann Thomas and Mindy Newell finally received credit. For the first time in history, a female artist was assigned to draw the series: Trina Robbins. From 1983 on, Dan Mishkin, Don Heck, Romeo Tanghal and Mindy Newell became main creators.

The entire franchise was rebooted to tremendous acclaim in 1987, by writers Greg Potter, Janice Race, Len Wein, Mindy Newell and writer-artist George Pérez. The feminist aspects of the character and her mythological roots became more outspoken. Trina Robbins and Colleen Doran also created a notable graphic novel: 'Wonder Woman: The Once and Future Story' (1998), which addressed spousal abuse. In 2007, Gail Simone wrote the new narratives, becoming the longest-running female writer of the franchise in the process. Another notable writer was Jodi Picoult. In the 2010s, J. Michael Straczynski, Phil Hester, Brian Azzarello, Meredith Finch and Greg Rucka became the new writers, while Cliff Chiang, Jim Lee, David Finch, Nicola Scott and Liam Sharp provided artwork. On 28 September 2016, writers Greg Rucka and Gail Simone made Wonder Woman a bisexual character and, in an official storyline, even let her officiate a same-sex marriage, drawn by Jason Badower. This marked the first time that a classic U.S. superhero came "out of the closet".

'Wonder Woman' #24 (July-August 1947).

TV adaptations

Although Wonder Woman has always been DC Comics' most recognizable female superhero, it took a long while before she was adapted into other media. In 1967, a TV pilot was made, 'Who's Afraid of Diana Prince?', scripted by Stan Hart and Larry Siegel, then rewritten by Stanley Ralph Ross. The pilot, however, never aired. Numerous other TV projects were considered and sometimes put in production, but since few business executives showed interest, they were usually abandoned. Part of the problem was that some of DC's editors felt embarrassed about Marston, especially given the fact that he wrote his controversial theories about women and submission in his stories. Increased media attention would inevitably draw attention to this old shame. In the early 1970s, thanks to creative involvement by respected feminist Gloria Steinem, 'Wonder Woman' refound direction and was able to shed its questionable roots. A successful live-action TV series was made, 'Wonder Woman' (1975-1979), starring Miss World 1971 Lynda Carter. Produced by ABC and afterwards CBS, it featured a catchy theme song by Norman Gimbel and Charles Fox. The TV show often depicted Carter spinning around to transform into her superhero outfit. Partially due to its campy nature, the show was a modest ratings hit and increased the character's global fame. It also inspired the disco single, 'Wonder Woman Disco' (1978) by The Wonderland Disco Band. Wonder Woman was also a supporting character in animated TV series like Hanna-Barbera's 'Super Friends' (1973-1986) and the 'Justice League' (2001-2006).

Film adaptations

It took until 2016 before Wonder Woman first appeared on the big screen, this time portrayed by Miss Israel 2004 Gal Gadot. In the live-action film 'Batman v. Superman: Dawn of Justice' (2016) by Zack Snyder, Wonder Woman played a major role, despite not being mentioned in the title. But contrary to Batman and Superman in this movie, she did receive her own pumping theme music, composed by Dutch deejay Junkie XL and composer Hans Zimmer. A year later, the heroine finally starred in her own live-action picture, 'Wonder Woman' (2017), directed by female director Patty Jenkins. The film was the best-received DC movie in years. It sparked renewed interest in the 'Wonder Woman' franchise and increased its comic book sales. Gadot's performance in particular became so popular that Wonder Woman received a bigger role in DC's next movie, 'Justice League' (2017), than originally planned. In 2020 Gadot reprised the role in the sequel 'Wonder Woman 1984' (2020), again directed by Jenkins. The latter movie also featured a cameo by 'Wonder Woman' TV star Lynda Carter.

'The Milk Swindle', a 'Wonder Woman' story from Sensation Comics #7 (July 1942).

Wonder Woman: controversial personality and bondage themes

While Wonder Woman is regarded as a feminist icon, her personality and female activism have been very inconsistent, depending on the writer. In some stories, she refuses to use violence, while in others she is an unapologetic master of combat. The heroine sometimes defends her gender very staunchly, while in other tales it is remarkably downplayed. Some authors have depicted her as highly clever, while others portrayed her as naïve and easily misled. Especially in Marston's stories, she is a walking contradiction. In her very first story, the independent woman falls in love with a man, Steve Trevor, with whom she starts a relationship. Wonder Woman is also designed as a lust object, while some of Marston and Peter's stories read like male fan service. The short-skirted title character shows some skin and is often drawn in revealing poses. Marston's preference for bondage appears in many stories. In countless scenes, characters are tied up, bound down, gagged or chained, sometimes several times in one narrative. On Wonder Woman's island, a special location, 'Reform Island' "re-educates" prisoners with "loving bondage and discipline". Wonder Woman herself doesn't escape the ropes either. She rarely fails to mention how "tight" she is tied up.

Comic critic Tim Hanley devoted an entire book to the topic, 'Wonder Woman Unbound: The Curious History of the World's Most Famous Heroine' (Chicago Review Press, 2014). He discovered that roughly 27% of Marston and Peter's stories include bondage, compared to only 3% of 'Captain Marvel', who also occasionally got tied up. Ropes, chains, lassos, girdles, tentacles, hypnosis, temporary paralysis, spanking, torture and even a very Freudian example of gooey ectoplasm in Wonder Woman #28 are staples of the series. As if the S&M undertones weren't already blatant enough, one of Wonder Woman's antagonists is a Nazi baroness who enjoys sadistic torture, Paula von Gunther.

'Wonder Woman' #3 (February-March 1943).

Even during the early years of 'Wonder Woman', the erotic innuendo already worried publisher M.C. Gaines. He sent Marston a list with suggestions on how to reduce the use of chains in the storylines. Criticism from outside the company didn't stay behind. In 1942, the National Organization for Decent Literature blacklisted 'Wonder Woman' as "disapproved for the youth", since the character "wasn't sufficiently dressed". In his influential anti-comics book 'Seduction of the Innocent' (1954), Fredric Wertham felt 'Wonder Woman' was troublesome for children, since it "promoted lesbianism". Naturally, ridicule of the comic series, which promoted feminism through scenes of chaste S&M bondage, has always been easy. Harvey Kurtzman and Will Elder lampooned the comic as 'Woman Wonder', published in Mad Magazine (issue #10, April 1954).

Defense of Marston

While some regard Marston as merely a horny old geezer who wanted to print his sexual fantasies under the pretense of "feminism", others have defended him. It has been suggested that the erotic undertones were merely a commercial consideration, a way of selling his ideas to as many readers as possible. Marston was once confronted with the fact that his male readers outnumbered his female ones. Rather than see this as a failure, he responded that this was perfect, "since men needed to understand the message the most." He felt: "You can't have a real woman character in any form of fiction without touching off a great many readers' erotic fancies." It should also be mentioned that the bondage in 'Wonder Woman' is always presented as something fun and playful. Wonder Woman sometimes clearly enjoys it, just for the sake of untying herself. This already sets it apart from more degrading and sadistic BDSM comics.

'The Icebound Maidens', from 'Wonder Woman' #13 (Summer 1945).

Legacy and influence

Wonder Woman remains a popular and enduring superhero today. Feminist Gloria Steinem felt that 'Wonder Woman' overall gave an inspiring message, since the character works together with other women and can rely on her own strength, if necessary. When Steinem founded the feminist magazine Ms., Wonder Woman was the first individual to appear on the cover of its debut issue in July 1972. The subtitle read: 'Wonder Woman for President'. Other celebrity fans have been novelist Jane Yolen (best known for 'The Devil's Arithmetic'), Olympic swimming champion Helen Wainwright Stelling, singer Judy Collins, comic artists Carol Lay - who wrote the book 'Wonder Woman: Mythos' (2003) - and Trina Robbins, who wrote the 2006 essay: 'Wonder Woman: Lesbian or Dyke?'. Among the series' male fans have been boxing legends Jack Dempsey and Gene Tunney. In 1978, artist Dara Birnbaum made the video art piece 'Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman', though this was based more on the 1970s TV show than the comics. In 2016, the United Nations named Wonder Woman a UN Honorary Ambassador for the Empowerment of Women and Girls. Actresses Lynda Carter and Gal Gadot were present during the ceremony hosted by UN secretary-general Ban Ki-Moon.

In 1999 an asteroid was named after W.M. Marston. In 2006 he was inducted in the Eisner Hall of Fame. His life story and that of his wives was adapted into a stage play, 'Lasso of Truth' (2014) by Carson Kreitzer. The production came with illustrations and set design by Jacob Stoltz and Ryan Zirgngibl, who also designed the poster to look like a comic book cover. In 2017, in the wake of the success of the 'Wonder Woman' movie, Angela Robinson directed a Hollywood biopic about Marston and his polygamous relationships named 'Professor Marston & the Wonder Women', which received excellent reviews, despite criticism of Marston's relatives who weren't consulted during the production process.

'Wonder Woman' #3 (February-March 1943).

Books about Marston

For those interested in William Moulton Marston and Wonder Woman, Jill Lepore's book 'The Secret History of Wonder Woman' (Knopf, New York, 2014) is a must-read. Another recommendation is Noah Berlatsky's 'Wonder Woman: Bondage and Feminism in the Marston/Peter Comics, 1941-1948' (Rutgers University Press, 2014).

Wonder Woman conference with Dr. William Moulton Marston, Harry G. Peter, Sheldon Mayer and editor M.C. Gaines.