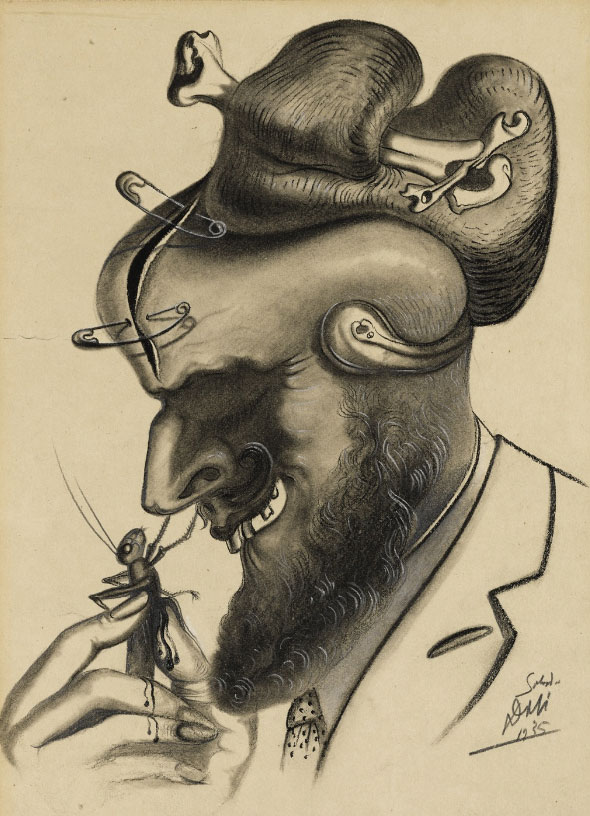

'Crazy Movie Scenario by M. Dali the Super-Realist' (American Weekly, 1935).

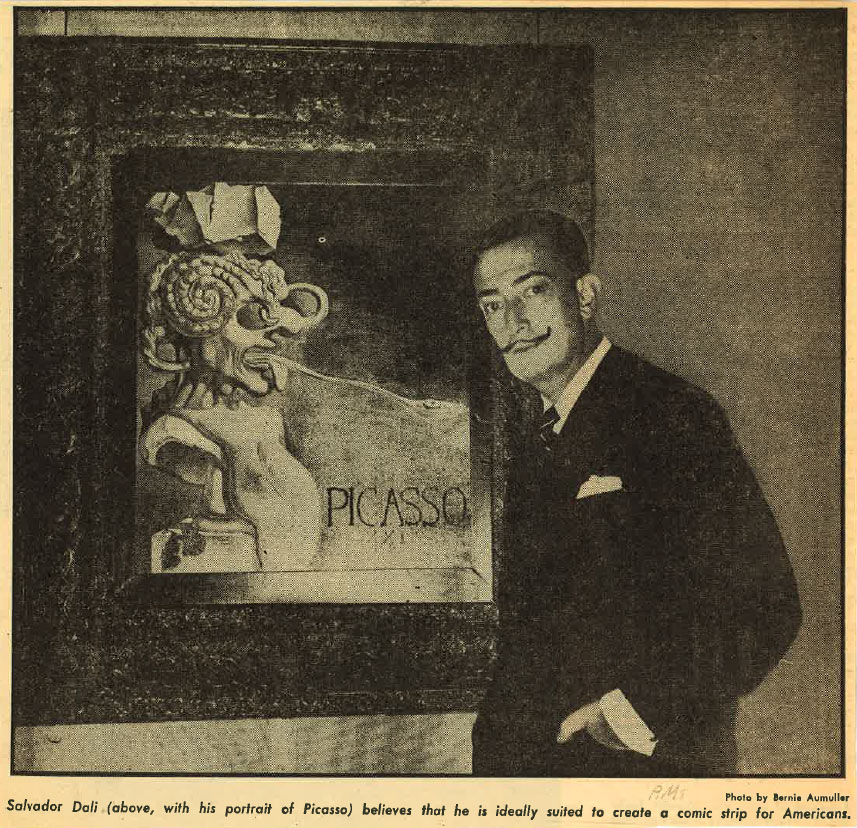

The Spanish artist Salvador Dalí was one of the most famous and influential Surrealists of all time. He made paintings and sculptures with absurd, dream-like imagery set in hyperrealistic desert and beach backgrounds. To bring his art to larger audiences, Dalí staged various publicity stunts. The artist worked in many different media, including photography, theater, film, fashion, advertising and book illustration. He is known to have created one comic based on an unused film storyboard, 'Crazy Movie Scenario' (1934-1935). Both his art and his cultivated eccentricity rank him alongside Pablo Picasso and Andy Warhol as one of the most famous 20th-century painters. Although often accused of commercialisation, Dalí captured the imagination of many people. His art is still an influence on many artists, including cartoonists and comic artists.

Early life and career

Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech was born in 1904 in Figueres, a small town in the Catalonian region. He was the son of a lawyer and notary. Before his birth, the Dalí family had another son called Salvador, who died at age seven from meningitis. His parents saw him as his reincarnation, which gave Dalí an unusual outlook on himself. Dali’s parents spoiled him when he was a child. As a boy he showed a gift for drawing. Painter family friends convinced his parents to send him to art school. From 1916 on, Dalí studied at the Academy of Figueres and, from 1922 on, at the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando in Madrid. However, the teenager was expelled in his second year. Dalí had stirred up his fellow students to protest against an artist he deemed "mediocre", but who was promoted to professor. In Gerona, he was jailed for a few weeks for being a dangerous troublemaker. By the fall of 1925, he was allowed back at the Academy, but was thrown out once again a year later. Dalí used to claim that the teachers failed to recognize his "genius".

Among Dalí's graphic influences were classic painters like Raphaël, Bronzino, Francisco de Zurbarán, Titian, Jean-François Millet and especially Johannes Vermeer and Diego Velazquéz. He also liked John Tenniel's 'Alice in Wonderland' illustrations and contemporaries like Pablo Picasso, Joan Miró, Juan Gris and the artists of the Cubist, Dada and Futurist Movement. In the late 1920s, he became more influenced by Surrealist artists like Joan Miró, Giorgio de Chirico, Yves Tanguy, Max Ernst and artists from past centuries who also made strange paintings, like Hieronymus Bosch and Giuseppe Arcimboldo.

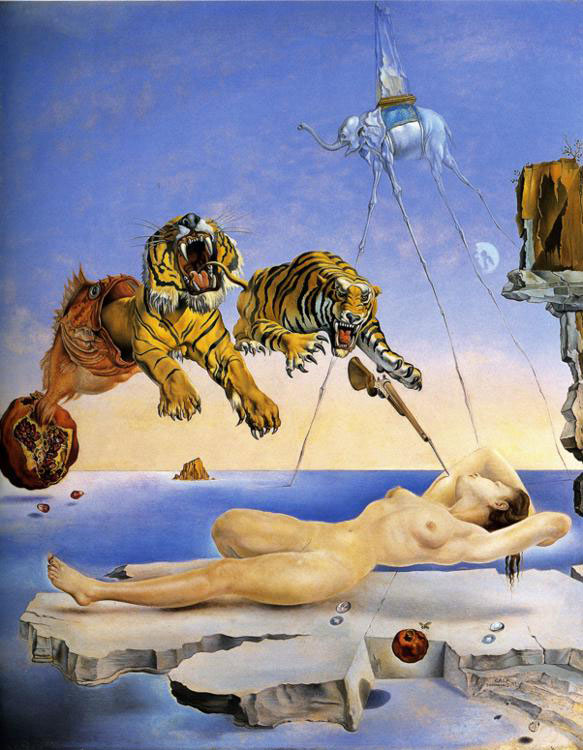

"Dream Caused By The Flight Of A Bee Around a Pomegranate a Second Before Awakening" (1944).

Surrealism

While Salvador Dali is a famous Surrealist, he didn't originate this artistic movement. It actually started in 1924 as two separate groups, one led by the French-German poet Yvan Goll, the other by the French writer André Breton. Most of their members were French, Spanish or German. In 1925, a third Surrealist movement was founded in Belgium, with René Magritte as its most famous representative. The Surrealists wrote and painted works that followed their stream of consciousness and were often inspired by dreams. In dreams people often find themself in abnormal situations which nevertheless look convincing. Surrealists mimic this seemingly normal atmosphere by drawing in a realistic style. Ordinary things are brought together in unusual combinations, often leading to an unsettling effect. The original Surrealists of the 1920s and 1930s were strongly influenced by Sigmund Freud's psychoanalytical theories about dream interpretation, particularly the symbolism of the subconscious. Later, his colleague Carl Gustav Jung explored these themes even further. Both Freud and Jung felt that dreams reveal people's inner personality and obsessions, particularly regarding fear and sexuality. In that sense, Surrealist art provides commentary on the human psyche.

In 1929, Dalí joined André Breton's group, since most of the artists he admired were part of this collective. The same year, he also met a Russian immigrant, Elena Ivanovna Diakonova, nicknamed Gala, who was married to Surrealist poet Paul Éluard. She soon left Éluard and in 1934, married Dalí. The painter regarded her as his muse. Gala she took care of his business affairs, which allowed him to fully concentrate on his art. Like his fellow Surrealists, Dalí also started painting strange, dream-like scenes with cryptic titles. Some imagery is inspired by things that haunted him, like locusts and a donkey carcass he once saw on the road, covered with ants. Other things merely fascinated him, such as bread, eggs, lobsters, telephones and rhinoceroses. Dalí also includes phallic symbols, nude women and buttocks in his work, despite being sexually distraught. As a child, photographs of venereal diseases in a medical book had traumatized him. In adulthood, this fear kept haunting him. In the 1920s, he had an intense friendship with the homosexual poet Federico García Lorca, though he always denied they were ever intimate. Even with Gala, Dalí rarely shared the sheets. She had several extramarital affairs, while he had young people organize orgies in his house, during which he preferred to remain a voyeur.

Salvador Dalí developed many recurring surreal images in his work, including melting watches, burning giraffes, elephants with mosquito legs, lobster-shaped telephones, and people with drawers in their body. He typically situated them in deserts or sandy beaches, inspired by his childhood holidays in Cap de Creus in North-East Spain. In 1930, Dali moved to the nearby bay town Port Lligat for additional inspiration. Inspired by his love for baroque painters, particularly Diego Velazquéz, Dalí took great care in depicting all his images as precisely and realistically as possible. In this aspect, he distinguished himself from other Surrealist painters. He sometimes directly referenced famous artworks by Velazquéz or Millet, or Hollywood stars like Mae West and Shirley Temple. He heightened the hypnotic effect through optical illusions and tricks in perspective. In 'Face of Mae West Which May Be Used as an Apartment' (1934-1935), a clever composition of furniture and paintings suggests the actress' facial features. In 'Slave Market with the Disappearing Bust of Voltaire' (1940) a bust of French philosopher Voltaire is hidden within the image. Apart from psychoanalysis, Dalí's interest in geometry, quantum mechanics and atomic theory led to even more mind-boggling visuals. From the 1950s on, he used Christian symbolism as well.

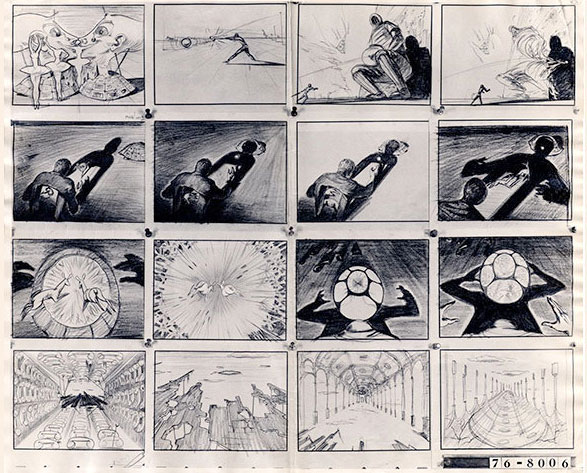

'Destino' storyboard art by Salvador Dalí.

Work for other media

Dalí increased his exposure by working in many different mediums. He designed theater sets for Federico Garcia Lorca's play 'Mariana Pineda' (1927). Together with director Luis Buñuel, Dalí made the first Surrealist film, 'Un Chien Andalou' (1929). He came up with some of its shocking imagery, such as the hand covered with ants. In the movie, Dalí also played a priest dragged across the floor. The most iconic scene - a woman's eye slashed by a razor – was, however, Buñuel's idea. 'Un Chien Andalou' became one of the most famous arthouse movies of all time and a genuine cult classic. Dalí also contributed to Buñuel's next film, 'L'Age d'Or' (1930), though not as much as he often claimed. During his stay in the United States, Dalí wrote a movie script for the comedy team The Marx Brothers, whose absurd comedy he genuinely liked. The film scenario 'Giraffes on Horseback Salad' (1937) was specifically intended for Harpo Marx, but was stalled in the development phase. In 2018, Tim Heidecker, Josh Frank and Manuela Pertega adapted this script into the graphic novel 'Giraffes on Horseback Salad' (Quirk Books, 2018).

Cover illustrations for This Week Magazine from 1945 and 1953.

In the early 1940s, Dalí collaborated with Walt Disney on an animated short, 'Destino', which also went nowhere. The studio finally released 'Destino' in 2003, but with a vastly different script. Dalí designed the famous dream sequence in the Alfred Hitchcock thriller 'Spellbound' (1945), but neither he, nor Hitchcock, were fully satisfied with it. In 1984, Alejandro Jodorowsky planned to adapt Frank Herbert's science fiction novel 'Dune' into a film, with designs by Moebius, guest roles by Gloria Swanson, Orson Welles and Mick Jagger, a soundtrack by Magma and Pink Floyd and with Salvador Dalí and model/pop singer Amanda Lear in the role of imperial couple. Yet Jodorowsky scrapped his initial idea and passed it on to David Lynch, who turned the film into something vastly different.

Dalí additionally created clothing for fashion designers Elsa Schiaparelli and Christian Dior. He wrote a novel, 'Visages Cachés' ('Hidden Faces', 1944), some autobiographical books, poetry and essays about art. He illustrated 'Les Bruixes de Llers' (1924) by Carles Fagses de Climent, Lautréamont's 'Les Chansons de Maldoror' (1933), Dante's 'La Divina Commedia' (1960) and 'Arabian Nights' (1964). He posed for an iconic photo by Philippe Halsman, 'Dali Atomicus' (1948), in which he floats in the air while a group of cats is splashed with water. Dalí wrote and performed as God in the “opera poem” 'Être Dieu' ('To Be God', 1974), with a libretto by Manuel Vázquez Montalbán and music composed by Igor Wakhévitch.

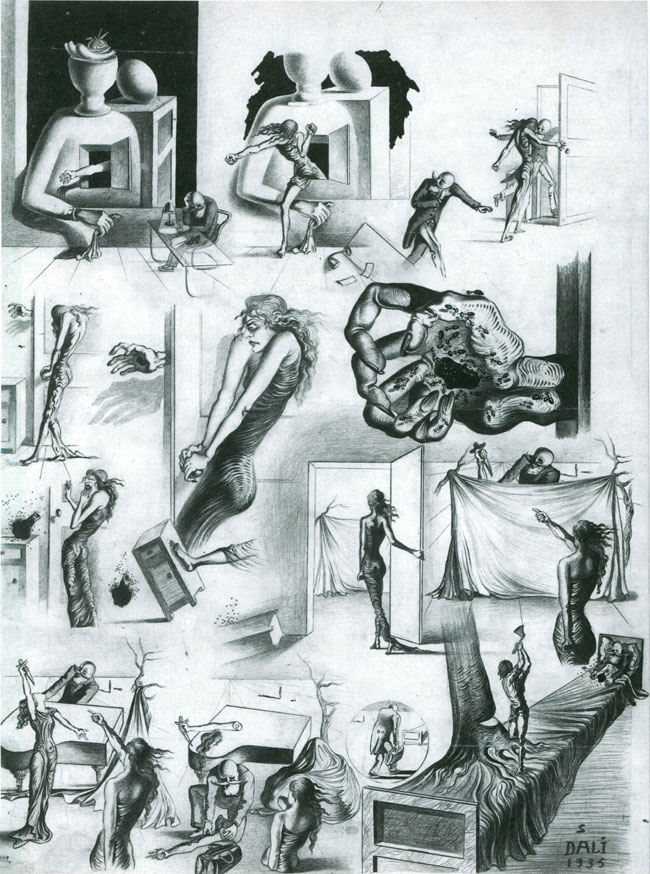

Studies for 'Les Mystères Surrealistes de New York' (1935).

Early comics

Salvador Dalí was interested in comics too. As a twelve-year old boy in 1916, he drew some text comics to entertain his ill sister. They are straightforward slapstick gags, which he presumably copied from a newspaper or magazine. These early works became better known in 1994, when the exhibition 'Salvador Dali: the Early Years' was held in London.

Les Mystères Surrealistes de New York, AKA Crazy Movie Scenario

As an adult, in 1935, Dalí made a work that was presented like a comic strip, but was actually a storyboard for a never-conceived film, 'Les Mystères Surrealistes de New York' ('The Surrealist Mysteries of New York'). The plot was based on the genre of silent movie serials like 'The Perils of Pauline' (1914-1915), more specifically the serial 'The Exploits of Elaine' (1914) by Louis J. Gasnier and George B. Seitz, at the time translated into French as 'Les Mystères de New York'. The plot of the original series revolved around a rich heir, Elaine Dodge, who collaborates with detective Craig Kennedy to find her father's assassin. In Dalí's hands, of course, this narrative was completely changed. He drew his storyboard as a series of loosely connected surreal images, separated by borderless panels. Between 16 December 1934 and 7 July 1935, the U.S. magazine The American Weekly, a Sunday supplement of The New York Journal, serialized Dali's storyboard under the title 'Crazy Movie Scenario by M. Dali the Super-Realist'. It was presented as a text comic, with written descriptions printed underneath the images. Much like a comic, it was also published in episodes.

Meeting with Hergé

In April 1962, when Dalí attended a reception in Brussels to mark the anniversary of advertising agency Vanypeco, he met Hergé, creator of the comic series 'Tintin'. A photo of their meeting was made too. A birthday telegram by Dalí to Hergé is on display in the Hergé Museum in Louvain-La-Neuve. However, according to Patrice Guérin's book 'Tintin Au-Delà des Idées Reçues' (Les Impressions Nouvelles, 2024), this specific telegram is a hoax. It lacks a date, address and isn't written in a typical telegram style. Another giveaway are the amount of typos, which a professional telegrapher wouldn't make. Guérin traces its origin to comedian Stéphane Steeman. On 17 January 1979, to celebrate the 50th anniversary of 'Tintin', Hergé attended a reception in the Brussels Hilton Hotel, where Steeman amused the comics veteran by reading fictional telegrams from celebrities of the day, whom Steeman also imitated. After the show, he gave them to Hergé.

Visit to Antica

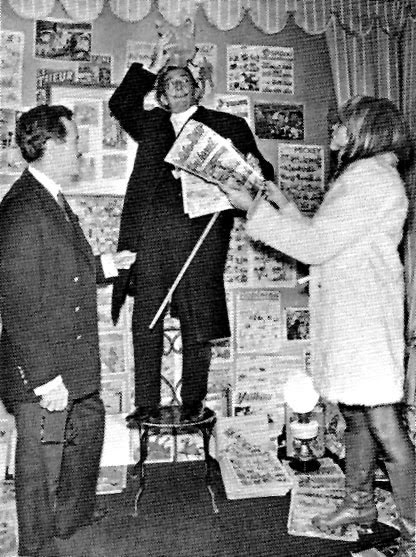

In 1967, while visiting the Antica book store in Paris, Dalí was photographed while making a statement about comics: "Comics will be the culture of the year 3794. So you have 1827 years in advance, which is good. In fact, that gives me the time I need to create a collage with these 80 comics here I'm taking with me. This will be the birth of Comic Art, and on this occasion we will hold a gigantic opening on 4 March 3794 with my divine presence at 19.00 hours precisely." The entire event was documented in the December 1967 issue of the magazine Collectioneur Français. However, it has not been recorded which comic books Dalí took with him.

Salvador Dalí in the Antica shop in Paris (1967).

Fame and eccentricity

By the mid-1930s, Salvador Dalí was world famous. His art was exhibited both in Europe and the United States. Within art circles, he was acknowledged as an important innovator, but he also became recognizable to general audiences. Not only through his endeavors in different media, but also because he was master in crafting publicity stunts. Dalí grew a long, pointy mustache and turned the tips up with wax, claiming it was an "antennae to pick up ideas." Salvador Dali's mustache is the first thing many people think about when they hear his name. Dalí made sure the press always had something to write about. He once shaved off all his hair, buried it on the beach of Cadaqués and had himself photographed with a sea urchin on his head. The madcap artist designed gadgets like nails with mirror reflections, shoes with coiled springs, a lobster-shaped telephone, gramophones displayed inside the carcass of an ox and a display window doll that could be used as a fish bowl. In 1929, he made a drawing of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, with the inscription: "Sometimes I spit on my mother's portrait, for fun." When Dalí's father read about it, he demanded a public apology. When Dalí refused, he was disinherited. Still, the painter was clever enough to exploit this scandal for what it was worth.

In 1934, when Dalí visited the USA, he handed out baguettes to the journalists waiting for his arrival in New York City. During a farewell ball on 18 January 1935, Dalí and Gala arrived wearing strange costumes. He wore a glass case on his chest, with a brassière inside, and Gala wore a baby doll on her head, as if she gave birth through it. Some reporters misinterpreted their bizarre outfits as mocking aviator Charles Lindbergh's kidnapped baby son, but Dalí denied this claim. In 1936, during a speech at a Surrealist exhibition in London, Dalí wore a diving suit, inspired by Buster Keaton's film 'The Navigator'. He almost passed out due to lack of air. In 1939, he designed the window of the Manhattan clothing shop Bonwit Teller, but got angry when he noticed that the owner had replaced parts of his installment with his own dolls. Dalí then pushed out the bathtub he had placed there, which crashed through the window. He was arrested, but soon released again. In 1955, he drove to a lecture in the Sorbonne University in Paris with his Rolls Royce full of cauliflower. Three years later, he gave another lecture in the capital, with a 12 meter long baguette nearby.

Salvador Dalí became the poster child of everything that was out of the ordinary. In interviews he often made outrageous remarks and always referred to himself in the third person. Whenever he talked English he spoke very slowly, putting strange emphasis on certain syllables and the letter "r". To most people, he seemed completely crazy, but in reality his behavior was premeditated. Although perfectly able to walk on his own, Dalí used canes to give himself a more royal appearance. He owned an ocelot and an anteater and was sometimes seen walking these pets in the street. One Christmas night he walked around in New York City and rang a bell from time to time to get himself noticed. Dalí also sought attention through self-mythologisation. Many self-proclaimed "facts" about his past have been debunked by biographers. He claimed lobster in chocolate sauce was his favorite dish, next to eating little birds, feathers and all. Dalí also said that he deliberately deprived himself from sleep by sitting in a chair with a spoon in his hand. If he fell asleep, the spoon would drop on the ground and wake him up again. That way he could keep himself in a dream-like state all day long. Many similar claims and anecdotes exist about Dalí, which may or not be urban legends. In one of his most honest quotes he stated: "The only difference between me and a madman, is that I'm not mad."

Salvador Dalí became such a media celebrity that other famous people wanted to meet him too. He met Sigmund Freud, Coco Chanel and later Hergé, Andy Warhol, John Lennon, Pope Pius XII, Pope John XXIII and Spanish dictator Francisco Franco. When he gave actress Mia Farrow a dead mouse in a bottle, her mother, Maureen O'Sullivan, wanted this gift removed from their house as quickly as possible. In the liner notes of his debut album 'Freak Out!' (1966), Frank Zappa cited Dalí as one of his influences. He once met the painter, who said he wanted to see Zappa's band play in the studio. Unfortunately, much to Zappa's frustration, they weren't allowed to enter the building at that time of the night. In old age, Dalí was also a good friend of rock star Alice Cooper.

Controversy

Although Dalí popularized Surrealism, his personal convictions clashed with other members of the movement. While other Surrealists were left-wing atheist republicans, Dalí claimed to be a Catholic monarchist. He liked the attention of rich and wealthy people, going so far as to declare himself proud of being "a snob." He was also fascinated with far-right dictators like Adolf Hitler and Francisco Franco. His painting 'The Enigma of Hitler' (1937) gave the Führer a mystical aura. Most modern artists in the 1930s were strongly opposed to Hitler, who regarded modern art as "Entartete Kunst" ("Degenerate art"). Franco too was more in favor of traditionalist painting. When in 1936 the Spanish Civil War broke out, the Surrealists sided with the resistance movement. Dalí didn't take a side, though when he heard that his good friend Federico García Lorca had been executed by Franco's troops he simply shouted: "Olé!". Dalí's colleagues wondered what was wrong with him. When they confronted him with his "sick" behavior, he turned it into a performance by wearing a wool sweater and sticking a clinical thermometer in his mouth.

Through this behavior, Dalí grew into a pariah. When Franco won the Civil War in 1939, Dalí sent him a telegram, praising him for "freeing Spain from destructive forces." For André Breton this was the final straw, and he threw Dalí out of the Surrealist movement. Oddly enough, once World War II broke out, Dalí still fled to the United States, apparently not that confident that Hitler would spare him. In the end it wasn't necessary, since Spain remained neutral during the conflict. In 1948, Dalí returned to his home country, where he became a vocal supporter of Franco. He visited the dictator three times, in 1956, 1968 and 1974, and even painted a portrait of his daughter. Dalí felt that after the generalissimo's death, Spain should become an absolute monarchy. In 1975, he supported Franco's execution of three E.T.A. terrorists, because he was "against democracy and in favor of the Holy Inquisition." His house was stoned and the painter once again fled to the USA.

Dalí also drew ire for constantly directing all attention to himself, as if he "invented" Surrealism. Fellow artists were disgusted how he shamelessly commercialized and downgraded the movement. Especially when Dalí visited the United States and stayed there during World War II, he would market his art in unprecedented ways. He left the psychoanalytical theories behind and just focused on making bizarre products. Other Surrealists were upset by his collaborations with fashion designers and Hollywood directors, but the pointy-mustached painter continued his commercial work. He designed covers for Vogue, appeared on the TV game show 'What's My Line?' and made TV commercials promoting Braniff International Airlines, Lanvin chocolate and Chupa Chups lollipops. He also designed the Chupa Chups logo and the advertising campaign for the 1969 Eurovision Song Festival in Spain. André Breton famously nicknamed him "Avida Dollars", an anagram of Dali's name, translating to "Greedy for Dollars". Many of Dalí's later paintings and sculptures were fabricated by other artists, after which he signed his name underneath or was photographed next to the finished works. And much like Pablo Picasso, he often paid expensive restaurant bills by simply giving the waiter a signed drawing.

Salvador Dalí's behavior is still a source of debate today. Critics and fans still argue whether he was a commercialized sell-out or just wanted to break outside the high art niche. Since he cultivated strangeness as part of his public image, it is uncertain whether he was serious or not. Sometimes he boasted of being "the greatest 20th-century artist", while in another interview he claimed to have contributed "absolutely nothing" to the world of art. Once he was approached by a female painter who wanted to show him her artworks, but he rejected her "because she was a woman". Yet at other times he treated women very respectfully. In his youth he was anticlerical, but in his late forties, he became a devout Catholic, influenced by Jesuit philosopher Pierre Teilhard de Chardin. His ultraconservative opinions are sometimes interpreted as yet another outrageous act. It has been argued that Dalí perhaps liked the absurdity of being in the presence of general Franco and popes Pius XII (1949) and John XXIII (1959). Others claim that his religious convictions were perhaps the only thing he was ever sincere about. Even his chastity could be understood in a Catholic context.

'The Temptation of St. Anthony' (1946).

Recognition

In the final years of his life, Dalí received several royal honors. He was named a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Isabella the Catholic (1964) and of the Order of Carlos III (1981). In 1979, he was inducted in the Académie Française des Beaux Arts (French Academy of Fine Arts). In 1982, King Juan Carlos of Spain named him a marquis. In Bolivia, a desert was named after him. Since 2013, his name also lives on in a crater on the planet Mercury.

Final years and death

Dalí and his wife Gala were married twice, with the second marriage being Catholic. Their relationship was more comparable to an overbearing mother and her son. Later in life, Gala grew more distant, spending more time with her extramarital lovers and even insisting that Dali only visit her if she gave him written permission. Her behavior added to Dalí's increasing loneliness and depression. Still, when Gala died in 1982, he was heartbroken, and lost all interest in life, even refusing food. In August 1984, an electrical fire broke out in Dali’s bedroom. He survived, but had severe burns. Salvador Dalí's final years were spent in ill health with Parkinson’s disease. In 1988, Dalí was back in the hospital, where he was visited by King Juan Carlos. The famous painter passed away in Figueres in early 1989, at age 84.

Drawing for The American Weekly (1935).

Legacy and influence

Despite his eccentricities and controversy - or perhaps because of it - Salvador Dalí is still acknowledged by many as one of the most important and influential artists of all time. In May 2007, he was voted to the 16th place in the 'El Español de la Historia' list ("The Greatest Spaniard in History"). Dalí's work is collected in the Dalí Theatre Museum in his birth town Figueres and in the Salvador Dalí House Museum in Port Lligat, Catalonia. St. Petersburg, Florida, also has its own Salvador Dalí Museum. He inspired the eponyms "Dali mustache" and "Dali-esque". For many people, along with René Magritte, he is synonymous with Surrealism. Thanks to Dalí, Surrealism became one of the most popular art movements of the 20th century. Many people relate more to this art style than any other, because life itself is quite absurd. To others, Surrealism is an intriguing break with mundanity. It allows people to look at everyday things in a different way, just by how they are juxtaposed in odd combinations.

For these same reasons, Surrealism is also irresistible to many creative minds. Salvador Dalí was a major influence on many visual artists, including George Brassaï, H.R. Giger, Damien Hirst, Jeff Koons, John Lennon, Overton Loyd and Andy Warhol. In the field of cartooning, he influenced Robert Crumb, Robert Williams, Ceesepe, Matt Furie, Terry Gilliam, Kamagurka, Herr Seele, Gummbah, Pitshou Mampa, Bill Morrison, Stewart Kenneth Moore, Luc Morjaeu, Alexis Olin, Gary Panter, Izzy Sanabria and Jim Woodring.

Salvador Dalí in comics and cartoons

Bob Clampett's groundbreaking animated Warner Bros. cartoon 'Porky in Wackyland' (1938) was directly inspired by Dalí's art. Stan MacGovern drew a 1947 four-panel comic strip based on the idea of what a comic strip by Dalí might look like. In 1968, Jim Steranko paid homage to Dali in Marvel's 'Nick Fury' issue #7. In France, Robert Descharnes and Jean-Michel Renault made a comic about Dali's life, 'La Vie de Salvador Dalí' (1986), published by BD Éditeurs. The Spanish comic artist Paco Roca drew a fictional biopic about the Spanish painter titled 'El Juego Lúgubre' ('Lugubrious Game', 2001), and the German artist Willi Bloess made 'Milestones of Art: Salvador Dali: The Paranoia-Method: A Graphic Novel' (Rakuten Kobo, 2013). In 'The Man with Kaleidoscope Eyes' (2008), Alan Aldridge describes how he once met Dali at a Nice airport, where he was challenged to an improvisational drawing contest. In Belgium, Dalí's art was the subject of the 'Suske en Wiske' story 'De Kunstkraker' (2002), drawn by Marc Verhaegen. A small biography about Dalí's life, 'This Is Dalí' (Orion Publishing, 2014) was made by Catherine Ingram, with comic strip illustrations by Andrew Rae. The French painter/comic artist Edmond Baudoin made a more realistic biographical graphic novel about the painter titled 'Dalí' (2016). In this book, he dismantles the mythical Dalí and brings him back to the simple human he was. Carlos Hernández Sánchez made 'El Sueño de Dalí' (Norma Editorial, 2018), while the same year the never produced film script by Dalí and Harpo Marx, 'Giraffes on Horseback Salad' (2018), was adapted into a graphic novel by Tim Heidecker, written by Josh Frank, drawn by Manuela Pertega and published by Quirk Books. Dalí is satirized in Willem's 'Les (Nouvelles) Aventures de l'Art' (Cornélius, 2004, 2019).

Salvador Dalí at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden Library.