Jim Woodring is an American comic artist, best-known for his long-running cult series 'Frank' (1990- ). He mostly draws pantomime comics set in surreal, nightmarish environments, inspired by his recurring hallucinations since childhood. His trademark "fine art" style is influenced by old European masters and surrealist painters. Woodring's comics have a strange, otherworldly, unpredictable atmosphere. The lack of dialogue gives his stories a hypnotic quality, mesmerizing readers until the final page. He remains a highly original and unique artist.

Early life

James William Woodring was born in 1952 in Los Angeles, as the son of a toxicologist and inventor. From a young age, he enjoyed animated cartoons by Walt Disney, Tex Avery and especially the Fleischer Brothers, whose surrealism had a strong impact on his own graphic and narrative style. Interviewed by Gary Groth for The Comics Journal (issue #164, December 1993), Woodring said that the 'Betty Boop' cartoon 'Bimbo's Initiation' (1933) was "one of the things that laid the foundation for my life's philosophy". As a boy, he liked cartoonists such as Ernie Bushmiller, Jack Kirby, Gil Kane, Graham Ingels and Mad Magazine (particularly the work of Jack Davis, Will Elder and Wallace Wood). Like many youngsters of his generation, his mind was shattered when he discovered the underground comix movement. Artists like Rick Griffin, Robert Crumb, Kim Deitch and Justin Green made him realize that different kinds of stories could be told, with deeper adult levels.

However, no event changed his life more than his 1968 visit to a retrospective about Dadaism and Surrealism in the L.A. County Art Museum. It introduced him to the work of Salvador Dalí, whom he singled out as his most important graphic influence, since Dalí's art actually encouraged him to draw. Among his other graphic influences are Hieronymus Bosch, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Rembrandt Van Rijn, Johannes Vermeer, Jean-Dominique Ingres and Boris Artzybasheff. Later in life, Woodring also expressed admiration for Pierre Roy, Cliff Sterrett, T.S. Sullivant, Harry McNaught, Jaime and Gilbert Hernandez, Mark Martin, Joe Matt, Mark Newgarden, Rachel Ball, John Dorman, Roy Thomkins, Peter Bagge, Terry LaBan, Seth, Chester Brown, Charles Burns, Al Columbia and Lat.

Woodring also took a lot of inspiration from novels by Victor Hugo, Malcolm Lowry and particularly Joseph Campbell. Since his twenties, he has been an avid reader of Buddhist, Hinduist and Taoist philosophy, from the Vedanta to the I Ching. It offered him a different perspective on life, which also seeped into his comics.

Hallucinations

Woodring's interest in the strange and the otherworldly began when he was four. From one day to the other, he suddenly had recurring intense hallucinations. Interviewed by Ross Simonini for The Believer on 1 February 2012, he recalled seeing horrifying things like glowing faces and shapes, frogs, toads, an enormous eye and a flying party horn with teeth. He also heard voices and was once convinced a lion had roared at his bedroom door. As a five-year old, he grew paranoid that his parents would murder him in his sleep. Another disturbing moment took place when a man in a workman's overall entered his room with a big wooden crate. Inside was Woodring's mother, naked, covered in red spots, eyes closed and a rictus grin on her face. The workman then told the boy she was dead. The plus side about these delusions was that they usually only lasted a short while. The down side was that he didn't understand where they came from, giving him trouble separating fiction from reality. Even images on TV or in film were confusing to him. For instance, he recalled thinking Bugs Bunny was human. The boy was convinced that dinosaurs lived in the mountains behind his house, because he saw them there occasionally. At one point these delusions "forced him" to drop out of high school.

Whenever Woodring told adults about his visions, they dismissed it as overactive imagination. He remembered telling his mother about the crate dream, which completely freaked her out. This traumatized him more than the dream itself. It has never been explained where his hallucinations came from. In his teens and again in his thirties he visited a psychiatrist, but it left him with no conclusive answers. In adulthood, he was diagnosed with autism and prosopagnosia, the inability to recognize familiar faces. Yet this still doesn't offer a medical reason for his nightmarish visions.

To cope with his fears, Woodring started to draw them on paper. This gave him the confidence that he could control them. After a while, he even enjoyed these hallucinatory experiences. When he was a teenager, they slowly but surely vanished. By that time, he started to miss them, since life suddenly seemed far more dull. Woodring deliberately tried to evoke his hallucinations again by drinking alcohol and taking LSD. One time he and a friend went drinking and fell asleep on a railroad track. Luckily, the train whistle woke them up and they quickly got off the rails again. Woodring later adapted this anecdote in his comic strip 'Too Stupid To Live'. After a couple of years, he realized drugs weren't the way to reach his childhood hallucinations again and quit this habit.

Jim - 'What The Left Hand Did'.

Early career

To earn a living, Woodring worked as a seasonal worker and garbage man. After his mother's death in 1974, he moved to Everson, California, where he and a friend did menial chores for people on a local farm. All the while he kept drawing, with aid of the Famous Artists correspondence school course, which he bought in a bookstore. Some of his earliest drawings were published in Petersen Publishing's hot rod magazine CARtoons and the two-weekly hippie tabloid Two-Bit Comics, sold for a quarter in vending machines on Hollywood Boulevard. Other early efforts appeared in the Los Angeles Free Press and the self-published The Little Swimmer. Looking back at his early work he considered it "pretty terrible."

One of his friends, John Dorman, worked in the storyboard department of animation studio Ruby-Spears, best known for TV shows such as 'Heathcliff and Dingbat' (1980-1981) and 'Alvin and the Chipmunks' (1983-1988). He helped Woodring get a job there as a storyboard artist and designer. Throughout most of the 1980s, Woodring animated at Ruby-Spears, even though he wasn't quite made for the job and most of their shows were forgettable. But it paid his bills and he met comics legends Jack Kirby and Gil Kane, who also worked at Ruby-Spears at the time. They gave him professional advice, which came in handy once Woodring left the animation industry by the end of the decade. Woodring said that the smog in L.A. was his direct motivation to seek cleaner air. He moved to Seattle, financed with income received from coloring Gil Kane's comic book adaptation of 'The Ring of the Nibelung' (DC Comics, 1990).

Jim - 'Seafood Platter From Hell'.

Jim

In 1980, Woodring brought out his first mini-comic, 'Jim', as a series of self-published zines. Like most autobiographical artists, he used himself as the protagonist. Some stories were directly inspired by things he witnessed during his delusions. Others were pure imagination. His early stories were still quite dialogue-heavy, leading to a lot of exposition. Through his connections with Gil Kane, 'Jim' received a professional release. Between 1987 and 1990, and again from December 1993 to May 1996, the 'Jim' books were published by Fantagraphics. They also included stories with recurring Woodring characters like Pulque - the embodiment of drunkenness - and the boyhood friends Chip and Monk. In 2014, all artwork was collected into one volume: 'Jim: Jim Woodring's Notorious Autojournal' (Fantagraphics, 2014). The book came with one new 24-page comic by the artist.

'Frank in the Wilderness' (Heavy Metal magazine, November 1993).

Frank

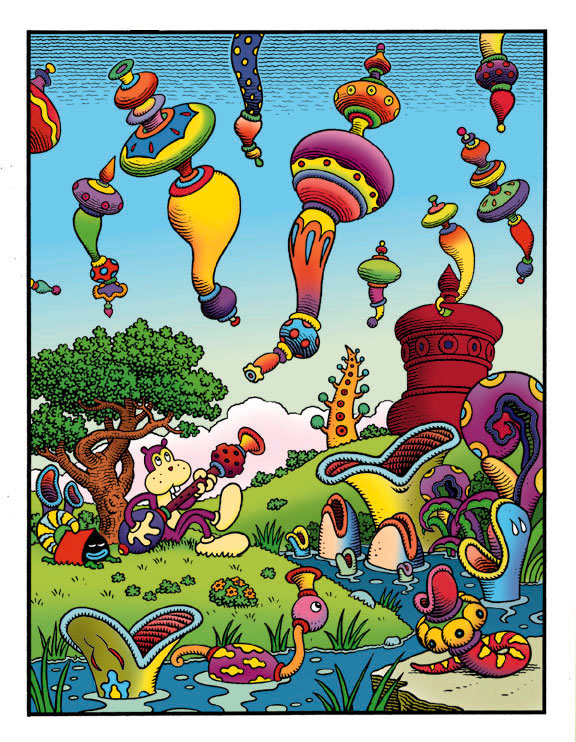

At the advice of Mark Landman, editor of Buzz Magazine, Woodring decided to make a comic strip that "looked like a normal comic, but wasn't". On the cover of 'Jim' (issue #4, October 1990), he introduced an odd, anthropomorphic character of an undetermined species. In Buzz issue #2 (February 1991), this buck-toothed, bear-like creature received his own spin-off series, 'Frank'. With this comic, Woodring finally found his style. All tales are set in a dreamlike universe which cannot be identified by location or time period. It appears to take place in a completely different dimension or planet. Fans often dub it the "Frankverse", but the official name is the "Unifactor". The backgrounds look like ancient European black-and-white engravings. Many buildings, plants and creatures are completely odd. Frank looks like a character from a Fleischer cartoon. His pets Pupshaw and Pushpaw are shaped respectively like a heart and a handbag. Frank frequently encounters Jivas, which are odd beings with bulbous spindles. His most recurring opponent is Manhog, a cross between a human and a large pig. The swine nevertheless acts more like an animal. He is a slave to his instincts and often creates havoc. Over the course of the series, Manhog becomes more of a tragic villain, since he lacks self awareness about his actions. A second recurring villain is Whim, whose face looks like a smiling half moon. Despite his fixated smile, he is completely untrustworthy. Another character, Lucky, has a more horrifying face which looks like the proboscis of an animal. Less of a threat, but more of a nuisance, are the Jerry Chickens who look like hens but each have a different geometrical shape.

Woodring prefers using anthropomorphic characters, because he never quite knows how to draw or approach human characters. In a 22 October 2005 interview, conducted by Daniel Robert Epstein for the website www.suicidegirls.com, he claimed: "I guess the reason why I don't draw people very much is because I don't understand them. I dont understand us, so I never quite know what to show." Occasionally Woodring uses very specific objects from our universe in his narratives, like a revolver or a bicycle. He would prefer to draw something more fitting to his characters' universe, but in the end readers need some kind of recognizable imagery to cling on, to avoid 'Frank' becoming completely incomprehensible. Woodring often uses certain shapes and patterns we as people know from primal recognition and sometimes have symbolic value. He also adds many autobiographical elements, like the frogs he saw in his childhood hallucinations. Alan Moore fittingly described Woodring's work as: "unsettlingly alien and intimately familiar."

Many stories take off with Frank leaving his house and wandering into the wilderness. He often encounters weird creatures or situations, which either frighten or threaten him. More than once he nearly loses his life. But in the next episode, he stupidly returns to the same locations, getting himself into trouble again. Frank's morbid curiosity parallels that of the author. Woodring often stated in interviews that fear isn't an unpleasant experience to him. He approaches it as an interesting learning experience, a thing of beauty, devoid of right or wrong. Just like mystery and humor, it's an essential component of his work. Woodring works as subconsciously as possible, without knowing where the stories will lead him. His comics avoid words, dialogue, speech balloons, time indications, onomatopoeia or explanatory descriptions. In an 8 July 2010 interview conducted by Jason Heller for www.avclub.com, Woodring explained: "I knew I wanted it to be something that was beyond time and specific place. I felt that having the characters speak would tie it to 20th-century America, because that would be the idiom of the language they would use, the language I use." In a 27 June 2011 interview conducted by Nicole Rudick for The Comics Journal, the artist explained: "Words can be deceptive - you start using words and people apply to them whatever meanings their prejudices dictate. Images are less open to interpretation in a way." He also stressed that the world itself in his comics isn't mute, just the way the comics are presented to the reader.

Right from the start, 'Frank' polarized readers. Some people dislike the creepiness. Woodring more than once met readers who told him that his work made them "physically sick." The innocent naïve Frank wanders through powerful charged landscapes in a permanent state of wonder. Woodring's drawings make these strange worlds just as convincing as a fever dream. His comics invite multiple re-readings, to discover new, interesting details. Thanks to the pantomime narration, they were easily translatable into many languages.

Between 1992 and 1994, Woodring and Mark Martin established their own comic magazine Tantalizing Stories as an outlet for his work. From 1996 on several book compilations of 'Frank' were published by Fantagraphics. 'The Portable Frank' (2008) had a foreword by Justin Green. Woodring's comics ran in magazines such as The Whole Earth Millennium Catalogue, World Wart, Weirdo, The Kenyon Review and Wired. Most 'Frank' comics are short stories, but in the 2010s Woodring made several full-length graphic novels with his characters. 'Weathercraft' (2010) had a stronger focus on Manhog and Whim, but in 'Congress of the Animals' (2011) everything centers around Frank. Woodring felt that he should give his hero a break for once and in the novel had him actually leave his familiar world to enter one more like ours. He meets a female partner, Fran, and gets a job in a dreadful factory. In 'Fran' (2013), the saga continues when they have an argument. Fran then runs off while Frank starts a journey to find her. 'Poochytown' (2018) is the third installment in this new saga.

Between 2000 and 2005, Japan's PressPop Music adapted nine 'Frank' stories into a series of animated shorts. While Woodring gave his blessing to the project, he otherwise had nothing to do with the production and just let the artists interpret everything accordingly. In 2005, the cartoons were released on DVD as 'Visions of Frank: Short Films by Japan's Most Audacious Animators' (2005). Some modest merchandising has been created around 'Frank' too, including a few toys and figurines created by Presspop.

Freaks

In 1992, Woodring adapted Tod Browning's classic horror film 'Freaks' (1932) into a comic book for Fantagraphics. 'Freaks' tells the story about a group of sideshow performers who eventually get revenge on those who mistreat them. What makes the film so unusual is that director Tod Browning hired actual freak show artists he knew personally to play the roles, including Siamese twins, a bearded lady, short people, limbless people and people with microcephaly. At its initial release, the film flopped and was banned in some countries, because audiences were shocked at the mere appearance of the sideshow performers. The movie was rediscovered in the 1960s, whereupon it was appreciated as a cult classic. Woodring wrote the script of the 'Freaks' comic book series, of which four volumes came out. The first installment follows the original movie closely, while the other three are completely new storylines. Francisco Solano Lopez illustrated the stories, while Woodring's wife Mary colored everything. A few decades later, Bill Griffith also made a graphic novel about Schlitzie, one of the sideshow performers from the 'Freaks' comic: 'Nobody's Fool: The Life and Times of Schlitzie the Pinhead' (AbramsComicArts, 2019).

Sciencefiction franchise comics ('Alien', Star Wars')

Woodring wrote some comics based on popular science fiction franchises, like 'Alien' and 'Star Wars', both for Dark Horse Comics. 'Aliens: Labyrinth' (1993-1994) featured illustration work by Kilian Plunkett, while 'Aliens: Kidnapped' (1997-1998) was drawn by Woodring, Justin Green and Francisco Solano Lopez. Woodring was a fan of the 'Alien' franchise and thus enjoyed working on these comics, particularly because it was much easier than his own work. Around the same time, he contributed to the mini-series 'Star Wars: Jabba the Hutt:' (1995-1996, collected in 1998 as 'Star Wars: Jabba the Hutt: Art of the Deal'), illustrated by Art Wetherell and Monty Sheldon, but this pleased him far less, except for being a well-paid job.

Scott Deschaine wrote the script for 'Blue Block' (Kitchen Sink Press, 1993), an indie comic book about freedom and liberation set in a dystopian future, illustrated by Woodring. In 1997, Deschaine and Woodring worked together again for the 12-page comic book 'Smokey Bear: Friend of the Forest' (1997), starring the mascot of the wildlife preservation campaigns of the U.S. Forest Service.

Woodring drew the children's comic 'Smokey Bear, Friend of the Forest' (1997).

Graphic and written contributions

Between 1991 and 1992, Woodring collaborated with comic writer Harvey Pekar and illustrated the stories 'Snake', 'Watching the Media Watchers' and 'Sheiboneth Beis Hamikdosh' for Pekar's 'American Splendor' series. He also went aboard with Dennis P. Eichhorn and drew 'Introducing Dennis Eichhorn' for the first volume and 'The Meaning of Life' for the third issue of 'Real Stuff'. Woodring wrote a personal homage to Robert Crumb in Monte Beauchamp's book 'The Life and Times of R. Crumb: Comments From Contemporaries (St. Martin's Griffin, New York, 1998). In 2002, the Serbian cartoonist Aleksandar Zograf published his collaborative comic book 'Jamming with Aleksandar Zograf', which featured artwork by himself, Woodring, Robert Crumb, Thierry Guitard, Wostok, Charles Alverson, Lee Kennedy, Peter Blegvad, Pat Moriarity, Chris Lanier and Bob Kathman. Woodring also made a contribution to Mad Magazine (issue #2, August 2018), writing and illustrating the article 'The Wisenheim Museum - Hoyden', where old-time Mad readers reminisce about their love of the magazine.

Album cover designs

Woodring enjoys different kinds of music, from classical to muzak. Among his favorite musicians are Captain Beefheart, Erik Satie and Bill Frisell. He illustrated the album covers of Bill Frisell's 'Gone, Just Like A Train' (1998) and 'Bill Frisell With Dave Holland and Elvin Jones' (2001). They turned tables with 'Trosper' (2013), a picture story by Woodring about a little elephant chased by monsters, for which Frisell composed a soundtrack. Woodring additionally illustrated the album cover of 'Ain't My Lookout' (1996) by The Grifters and 'Songs for Sorrow' (2009) by Mika. In 2013, Woodring took a different direction and created a comic book, an animated short and three figurines, inspired by the artwork of 'Fade' (2013), an album by Yo La Tengo.

Recognition

In 1993, Woodring received two Harvey Awards, one for "Best Colorist", while his book 'Tantalizing Stories Presents Frank in the River' won "Best Single Issue or Story". He additionally was awarded an United States Artists Fellowship (2006), Inkpot Award (2008), Genius of Literature (2010) and the Lynd Ward Graphic Novel Prize (2014).

Other activities

Woodring worked as an essayist and journalist for the Fantagraphics comic magazine The Comics Journal. He and Bob Rini also founded the Friends of the Nib, a salon for cartoonists in Seattle. Among its members have been Bruce Bickford (best-known for his clay-mation cartoons for Frank Zappa), Max Clotfelter, Mark Campos, Heidi Estey, Ellen Forney, Jason T. Miles and Max Woodring. Woodring is also active in software. He created the Comic Chat program for Microsoft. Woodring also designs toys and paintings. Some of his toys have been sold in Japanese vending machines.

Silkscreen print of 'Frank', made for Galerie Lambiek, Amsterdam (see photo below).

Legacy and influence

In the United States, Jim Woodring influenced Daniel Clowes, Sophie Crumb, Matt Groening (who placed 'Frank in the River' at number 94 in his personal list of '100 Favorite Things'), Sammy Harkham, Joe Matt and Rich Powell. One book collection, 'The Frank Book' (2003), has a foreword by film director Francis Ford Coppola ('The Godfather', 'Apocalypse Now'). Another celebrity fan is actor Jeff Bridges (best-known as The Dude in 'The Big Lebowski'). Woodring also found admirers in Belgium (Kim Duchateau), Canada (Dave Cooper), Germany (Andreas Rausch), The Netherlands (Merel Barends) and Norway (Jason). Woodring's work has been praised by veteran cartoonists like Joe McCulloch, Alan Moore, Robert Williams and Scott McCloud, who once called him "the most important cartoonist of his generation." In April 2011, Woodring started his own blog. His son Maxfield Woodring is also active as a cartoonist.

Documentaries about Jim Woodring

For those interested in Woodring's life and career, the documentary, 'The Lobster and The Liver: The Unique World of Jim Woodring' (2010) by Jonathan Howells, is highly recommended.

From 26 May through mid July 2000, Kees Kousemaker's Gallery Lambiek in Amsterdam hosted Jim Woodring's 'Frank by the River' exposition. A special silkscreen was released, signed by the artist.

Frank by the River expo in Gallery Lambiek (2000)

www.jimwoodring.com