Willem is a Dutch political cartoonist, who started his career as part of the 1960s Dutch Provo movement, but since the 1970s mostly published in French magazines like Charlie-Hebdo, Libération and Siné-Hebdo. It consequently made him one of the oldest and longest-running political cartoonists in the Dutch as well as the French press. Willem is also one of the most controversial. His ecoline-drawn cartoons are notorious for their sardonic tackling of taboo topics. They often feature shocking scenes of pornography and violence. The anarchist went into legend when he depicted Dutch queen Juliana as a prostitute (1966) and was promptly sued, making him, along with Peter van Reen and Theo Gootjes, one of three Dutch political cartoonists to be brought to court for libel. In 2015, he unwillingly achieved world fame when he survived the terrorist attacks on the Charlie Hebdo office in Paris "by missing his train", a story which, just like his Juliana cartoon trial, is often presented incorrectly by the press. Willem is also a productive comic artist, often using the format in his political cartoons. But he additionally released several comic books about his own fictional characters Fred Fallo ('Jack L'Eventreur', 1971) and Daan van Dalen ('Dick Talon', 1971). Willem should not be confused with another Dutch artist who uses the same pseudonym, namely Willem Verburg.

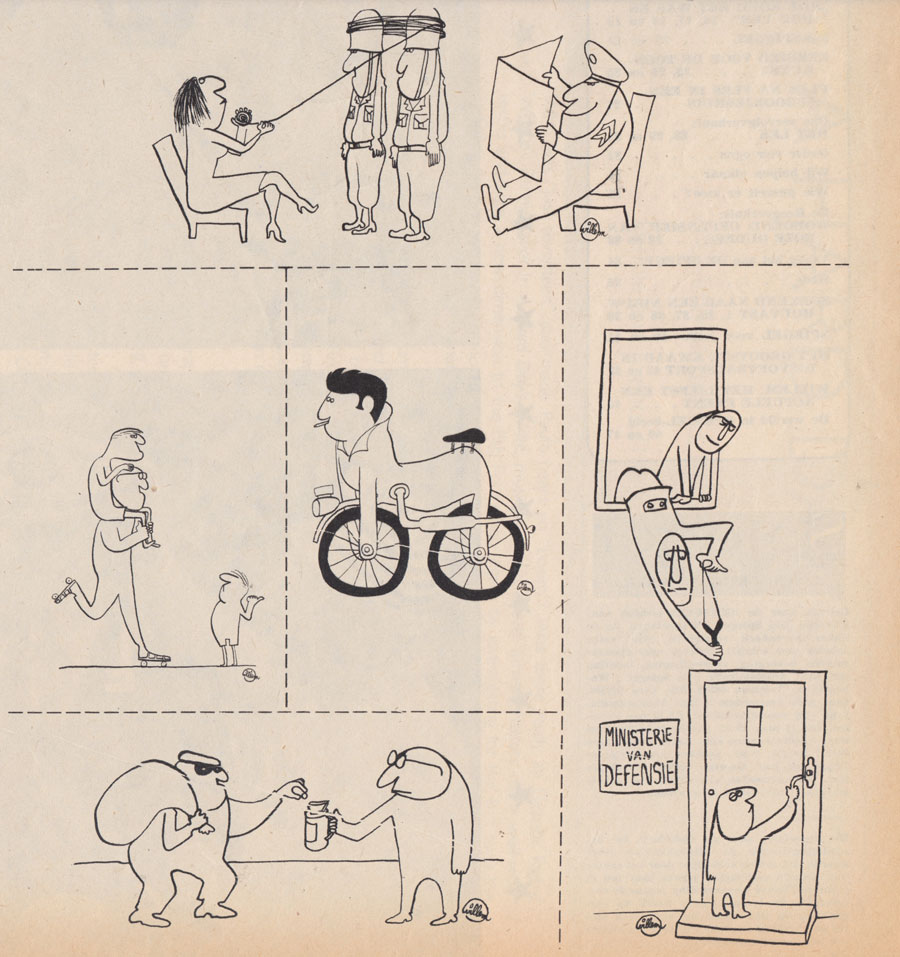

Comic strip by Willem.

Early life and career

Bernhard Willem Holtrop was born in 1941 in Ermelo in De Veluwe, one of the most conservative regions of The Netherlands. He was named after Dutch prince Bernhard, coincidentally the most controversial member of the Dutch royal family (about whom Willem would later make an entire comic book). Willem's father was a devout reformed Christian who worked as a physician. During World War II he was active in the resistance and sheltered a Jewish couple in his home. The Nazis jailed him in prison camp Vught for three months, despite having no concrete proof. After the war he took his eight-year old son to Vught to show him where he had been jailed and where prisoners were executed. Willem suspected that it was part of his father's traumatic process. Through his dad's profession, Willem also saw a lot of medical photos as a kid. Pictures of births, injuries and diseases. All these experiences gave him a lifelong fascination with World War II and the macabre in general.

Early cartoons in De Spiegel (10 August 1963).

Though his father kept more pleasant pictures too. Willem enjoyed paging through Life Magazine and the engravings in his father's Bible. He became an avid collector of press photos, historical photos, travel landscapes, pornographic and violent scenes. Among his graphic influences were Albert Hahn Sr., Leendert Jordaan, David Low, Boris Yefimov and later Manfred Deix, Francis Masse, René Pétillon, Siné and Roland Topor. As a student at the boarding school Instituut Hommes in Hoogezand, he was expelled for making a "pornographic paper". While drafted, Willem published his first cartoons in November 1961 in a column titled 'Humor uit het Soldatenleven' in the army magazine De Legerkoerier. The same year his first paid cartoon appeared in Het Vrije Volk. Between 1962 and 1967, Willem studied fine arts and advertising at the Academies of Arnhem and 's Hertogenbosch, while publishing in the legendary Dutch student magazine Propria Cures. His other early drawings appeared in De Spiegel, Nieuwe Rotterdamse Courant, NRC Handelsblad, Algemeen Handelsblad, Liberaal Réveil, Pols and Vrij Nederland.

Provo

Like many youngsters in the 1960s, Willem applauded the revolutionary changes and free-spirited atmosphere. He discovered Hara-Kiri magazine, underground comix and got involved with the Provo movement. Provo agitated conventional people with their provocative happenings, which matched Willem's own anarchic convictions. After noticing their official magazine, Provo, lacked a house cartoonist, he applied for it. In December 1965 he debuted in its pages. Willem additionally designed flyers and posters for the movement, including the iconic illustration 'Provoceer!' ("Provoke!"), which depicts a tiny man chopping down a policeman's legs with an ax.

The infamous 'Queen Juliana as a prostitute' cartoon (1966), which led to a court case.

God, Nederland en Oranje

Willem and fellow Provo Hans Metz soon founded their own Provo magazine in September 1966. The title, "God, Nederland en Oranje" ("God, the Netherlands and Orange"), was originally a patriotic slogan used by Dutch people who worshiped Christianity, their country and the royal family, but here it was obviously used ironically. The magazine specialized in outrageous columns and cartoons. Apart from Willem, it published subversive drawings by Willem van Malsen, Ab Tulp, Pierre, Midas, Picha and Roland Topor. God, Nederland and Oranje disturbed the authorities so much that the police confiscated five of the in total 10 issues. In the very first issue two cartoons by Willem led to a court case. The first one depicted a swastika-shaped policeman chasing a little man. The second one portrayed Dutch queen Juliana as a window prostitute, with her prize being the annual cost of the Dutch monarchy. He was charged with insulting public authority and lèse-majesté.

According to legend, Willem was fined for lèse-majesté, but never paid the required sum and instead fled to France. Many newspapers at the time reported this verdict and it has been repeated in dozens of articles, books and documentaries since. In reality, Willem was acquitted by the judge for lèse-majesté in March 1968, but sentenced to a 250 guilders fine for the "police swastika" cartoon. Even on appeal Willem lost, so he paid the sum. Incidentally, cartoonist Pierre was also sued for a similar cartoon in issue #5 (March 1967), depicting the queen as a striptease artist singing: "Ich bin von Kopf bis Fuss auf Guldens eingestellt" (German for: "I'm from head to toe only interested in guilders", a reference to the 1930 song 'Ich bin von Kopf bis Fuss Auf Liebe Eingestellt' by Marlène Dietrich). In March 1968, the final issue of God, Nederland en Oranje was printed.

'Billy the Kid' (1968), caricaturing U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson. Translation: "What? What did you say? Did I hear you say something about politics? Be glad that you're born in a democratic country, where you can calmly discuss these matters!".

Hitweek (Aloha) / De Nieuwe Linie

From 1967 on until the end of the 1970s, Willem's comics and cartoons appeared in the Dutch pop weekly Hitweek (later Aloha) and progressive opinion weekly De Nieuwe Linie. When the Provo movement dissolved, they remained the only long-running counterculture magazines in the Netherlands where he could still publish his anarchic drawings. During the 1960s and 1970s, most comics he made for them were translations from work which originally appeared in L'Enragé, Charlie Hebdo and Charlie Mensuel. Willem's first complete comic book, 'Billy the Kid, Of Hoe Een Eenvoudige Jongen Uit Texas de Maarschalksstaf In Zijn Ransel Vond en Er Mee Op Kruistocht Ging' (Polak & Van Gennep, 1968), was a satire starring U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson as a cowboy/Fascist dictator. The French publishing company L'Apocalypse simply published it under the title 'Billy the Kid'. For Aloha, Willem drew the political comic strip 'De Avonturen van Piet Por', which ran under the French title 'Les Aventures de Tom Blanc' in Hara-Kiri/Charlie Hebdo. In 1972 a book compilation was published by De Harmonie and in 1973 in French by Éditions du Square.

Daan van Dalen/ Dick Talon, Barnstein and Fred Fallo/ Jack L'Eventreur

In 1971-1972, Willem created his best-known recurring comic characters: the naïve simpleton Daan van Dalen (known as Dick Talon in French), his detective brother Guust van Dalen (Gaston Talon), black bearded terrorist Barnstein and the flirtatious mustached scoundrel Fred Fallo (Jack L'Eventreur). His anti-heroes starred in turbulent stories full of sex, drugs, violence and politics, including fights against neo-Nazis.

Prins Bernhard

In 1976, De Nieuwe Linie published a series of cartoons about Dutch Prince Bernhard and his involvement in the Lockheed corruption scandal. When they were compiled into a book, 'De Avonturen van Prins Bernhard' (1977), many Dutch magazines refused to prepublish, let alone promote it. The work was also published in France as 'Les Aventures de Prince Bernhard' (Éditions du Square, 1977).

'Daan van Dalen' (De Topeloeng, 1976).

Move to France

In May 1968, during the student demonstrations in Paris, Willem's work started appearing in the French press too, namely the magazines L'Enragé (edited by Siné), Hara-Kiri and (from 1969 on) Charlie Mensuel. In 1969, he eventually moved to France. Contrary to urban legend, he didn't flee to avoid paying a fine for making an offensive cartoon about Queen Juliana. After all, he wouldn't have been able to leave his country in the first place. But the trial was one of three good reasons to move to France. Willem liked France better because there were more magazines willing to publish his anarchic cartoons. He also felt French politics were more inviting to satirize because there are "genuine crooks and gangsters", compared with the rather bland Dutch government.

Charlie Hebdo covers of 12 November 1980 and 5 March 1997. The first cover depicts newly elected U.S. President Ronald Reagan with the line: "Reagan puts women back in their place." The second cover mocks extreme-right politician Jean-Marie Le Pen with the line: "Le Pen sees Jews everywhere", while he says: "And all that while missing an eye!", in reference to his real-life blind eye.

Hara-Kiri / Charlie Hebdo

Joining Hara-Kiri in 1968 and staying with this magazine after its 1970 name change into Charlie Hebdo, Willem became the longest-running contributor and, since 2015, sole survivor from the pioneer years. He was also the only regular non-French contributor and the only Dutchman. Willem received his own columns, 'Revue de Presse' and 'Chez Les Esthètes'. For many years, he made the weekly 'Autre Chose' section, an illustrated editorial chronicle about exhibitions, fanzines, obscure publications and other pop culture memorabilia. Originally, his French was very rusty, so his comics had frequent spelling and grammatical errors. His colleagues nevertheless felt this was part of the charm and his personal stamp, so they kept them in. Funny enough, in the early 1970s Gérald Poussin was rejected from Charlie Hebdo, because editors told him "we already have someone who makes grammar mistakes." Willem has always felt most in his element at Charlie Hebdo, because he is allowed to do what he wants, whereas other magazines are more likely to reject certain cartoons. Les Humanoïdes Associés collected a decade's worth of Willem's Charlie Hebdo output in 'Complet! La Revue de Presse de Willem. Charlie Hebdo, 1969-1981' (1984). L'Association compiled several of his political comics into the books 'Coeur de Chien' (2004) and 'Le Prix du Poisson' (2010).

Charlie Mensuel

Since 1970, Willem was also a mainstay in Charlie Hebdo's sister magazine Charlie Mensuel. He prepublished many of his comics starring Fred Fallo, Barnstein and Daan van Dalen under their translated names. One 'Fred Fallo' story in issue #64 (1974) was co-created with Joost Swarte. In 1981 Willem succeeded Wolinski as Charlie Mensuel's third and final chief editor. He took over from issue #146 on and stayed until the 152th and final issue.

Surprise

In February 1976, Charlie Hebdo/Mensuel brought out a sister magazine titled Surprise, of which Professeur Choron and Willem were the chief editors. Surprise wanted to be even more outrageous than its mother magazine, featuring mostly comics by European underground artists like Joost Swarte, Ever Meulen, Chapi, Loulou, Roland Topor and Kamagurka, but also U.S. material by Kim Deitch, Robert Armstrong and Justin Green. Although it was mostly Willem's magazine, he was so preoccupied with editing that he didn't draw for it, not even a cover. Surprise caught the attention of French Minister of Interior Michel Poniatowski, who banned its sales among minors. Yet sales were already nil to begin with. To nobody's surprise, the fifth and final issue rolled from the presses in October of that same year.

B.D.

On 10 October 1977, another sister magazine was launched: B.D. From the first until the 26th issue it featured a two-parter mafia comic strip by Willem set in New York City, titled 'Rats Hamburger' (1977-1978).

Charlie Hebdo terrorist attacks

In 2006, Charlie Hebdo brought out a special issue in which they mocked Islam and the Prophet Muhammad, in a direct reaction to the global outrage sparked by cartoons which had ridiculed the same subject in the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten and which had forced the editors and cartoonists to go into hiding. Now the editors of Charlie Hebdo found themselves sued and subject of death threats. In April 2011, a molotov cocktail attack burnt out the offices, but without any victims. The Parisian police put them under police protection, but on 7 January 2015 two Muslim fundamentalist terrorists broke inside the magazine's office, murdered the police officers (including Ahmed Merabet, himself a Muslim) and nearly all editors, cartoonists and writers inside. In total 12 people were murdered and 11 injured, including several of Willem's best friends and colleagues. He survived the attack, because he wasn't present. Many media at the time claimed that Willem "had missed his train and was late for work", but in reality he never attended their weekly editorial meetings. Some reporters confused him with cartoonist Luz, who indeed was late for work that tragic day. But Willem was traveling to Paris by train that day, with the intention of delivering a couple of cartoons to the office of Libération, Charlie Hebdo and Siné Mensuel and attending a dinner for former organizers of the Comics Festival of Angoulême.

The terrorist attacks sparked universal outrage and sadness, including from the majority of Muslims. It not only made Charlie Hebdo suddenly world famous, but also gave Willem more unwanted media recognizability, for he was the oldest-surviving veteran cartoonist of the publication. Apart from that, he was also the most well-known Charlie Hebdo contributor in both the Dutch-language and French-language press. He was therefore frequently interviewed and confirmed to everyone that "both I and Charlie Hebdo will continue. We have to." Only a week after the tragedy, he and the surviving editors joined forces to publish the next issue. Since they had to work with fewer people than before, he, Luz and Catherine Meurisse were forced to make more cartoons than usual to fill in for the others, though reprints of the deceased contributors were added too. Willem rejected all public support from politicians, religious leaders, organizations and all "so-called new friends, because it made him throw up." He felt most were crocodile tears and people who never dared to support them before and often obviously had no clue what Charlie Hebdo was all about. He didn't care about the terrorists' background either: "They are idiots, so-called religious people real Muslims don't want anything to do with." For the same reasons he co-signed a petition on 12 January 2015 by several French writers and cartoonists against the German islamophobic movement Pegida, who tried to exploit the tragic events by stirring up racial hatred.

Willem also refused any police protection or bulletproof vests, because if someone wanted to kill him, he would find a way, anyway, since they hadn't managed to rescue his colleagues either. He gave the terrorists a firm middle finger in his next book, 'Willem Akbar!' (Les Requins Marteaux, 2015). In the homage book, 'Charlie Hebdo: Même Pas Peur' (Les Échappes, 2016), his cartoons appeared alongside those by his fellow cartoonists. He also contributed to the tribute book 'Bernard Maris Expliqué à Ceux Qui Ne Comprennent Rien à L'Économie' (2017) by Gilles Raveaud, an homage to the economic columns of his murdered colleague Bernard Maris.

Comic strip mocking far-right politician Jean-Marie Le Pen and his stance on bringing back the death penalty. The brainless crowd shouts: "Understood, chef! Death penalty only for French people!!"

Libération

Between 1981 and 2021, Willem was house cartoonist of the left-wing newspaper Libération, where his work appeared under the title 'L'Oeil de Willem' (literally "Willem's Eye"). Between 1993 and 2002 he was a travel journalist for the magazine, making voyages to Cameroon, the Ivory Coast, the Baltic States, New Hampshire and Russia. He kept an illustrated diary which, compared with the general tone of his work, is much milder and accessible to general audiences. In the Netherlands, the reports were published in HP/De Tijd and Vrij Nederland. The trips formed the basis of several cartoon books, such as 'Quais Baltiques' (Les Petits Libres, 1994), and 'Op Stap Met De Razende Reporter' (De Harmonie, 2002). Later titles like 'Ailleurs' (Cornelius, 2002) and 'Partout' (Cornelius, 2008) covered countries like China, Netherlands, Ireland, Vietnam, Italy, Finland, Norway, Burkina Faso and Estonia. 'Avignon' (Cornelius, 2011) collects all graphic reports he made for the Festival of Avignon.

Over the years, Libération's publisher, Les Requins Marteaux, has brought out regular compilations of Willem's political cartoons, including 'Willem à Libération' (Albin Michel, 1989), 'Eliminations' (2002), 'Merci Ben Laden!' (2002) and 'Destruction Massive' (2003), which mostly dealt with U.S. President Bush Jr. and his war on terror against Osama Bin Laden and Saddam Hussein. Closer to home, 'Élections Surréalistes' (2003) poked fun at the 2002 presidential elections, when Jacques Chirac faced off against the far-right candidate Jean-Marie Le Pen. Chirac's successor Nicolas Sarkozy was lampooned in 'Sarko, L'Increvable' (2006), 'Le Roman Noir des Élections' (2008) and 'Casse-Toi, Pauvre Con!' (2009), while François Hollande was ridiculed in 'Plus Jamais ça!' (2012) and 'Le Pire Est Derrière Nous' (2014). President Emmanuel Macron wasn't spared either, as 'Macron, L'Amour Fou' (2018) proved. In 2021, Willem announced his retirement from Libération. His spot is taken over by Charlie-Hebdo cartoonist Corinne Rey, AKA Coco.

'Le Bec Cloue', from 'Les Crimes Innomables'.

Other publications

In the 1970s, Willem's cartoons & comics also appeared in Joost Swarte's underground comic book Cocktail Comix (1973). A decade later, he published in Rigolo!, Psikopat, Métal Hurlant (France), Pardon Lul, Joost Swarte's Moderne Kunst (Netherlands) and Robert Crumb's Weirdo (USA). He was one of many cartoonists who contributed to a "chain comic" in Raw (issue #8, September 1986), titled 'Raw Gagz'. In the 2000s and 2010s, his work also ran in BoDoï, Fluide Glacial, L'Immanquable and Siné Mensuel. His work is also a regular occurence in the Le Monde, L'Écho des Savanes, HP/De Tijd and Vrij Nederland. Ever since his move to France, his work has been collected in a great many books by publishers like Éditions du Square, Albin Michel and Cornélius. Among his collections are 'Chez les Obsédés' (Éditions du Square, 1971), 'Drames de Famille' (Éditions du Square, 1973), 'La Crise Illustrée' (Éditions du Square, 1975), 'Terreur Aveugle' (Éditions du Square, 1979), 'Plaisir d'Esthète' (Dernier Terrain Vague, 1982), 'Les Crimes Innommables' (Albin Michel, 1983), 'L'Amour sera Toujours Vainqueur' (Les Humanoïdes Associés, 1984), 'Le Monde en Images' (Albin Michel, 1991), 'Tout Va Bien' (Albin Michel, 1997), 'La Droite Part en Couilles' (Bichro, 2000), 'La Paix dans le Monde' (L'Atalante, 2002) and 'Appétit' (Humeurs, 2004).

'Les Crimes Innommables', 'L'Amour Sera Toujours Vainqueur' and 'Fred Fallo Staat op Springen'.

Thematic historical comics

Over the decades, Willem has published a variety of comic books based on historical themes. Most imagery is presented as a series of small pictures, directly copied from real-life photographs but drawn in his own style. In the center or corners of the page are usually one or two splash panels. These panels are more fantasy-driven and subvert photographic imagery into a symbolic metaphor. Willem presents all pictures as a kind of twisted pen-and-ink photo collage. The idea came from his childhood fascination with photographs in Life Magazine and newspapers. Since he couldn't read yet and was too young to understand the political context, these images had a mysterious aura. His own cartoons evoke the same atmosphere. Most press photos he traced only have one subtitle for each chapter to indicate a theme. They show pictures which have become part of our collective memory or show familiar politicians in unusual contexts or settings.

The earliest work in this fashion is 'Storm over Batavia!' (De Harmonie, 1975), which deals with the Japanese invasion of the Dutch Indies (nowadays Indonesia) during World War II. In 1985, Willem published 'Lust en Strijd' (De Harmonie, 1985), published in French as 'N'Oublions Jamais' (Éditions du Square, 1985), arguably the most controversial book from his career. It features many harsh drawings about the Second World War, mocking warfare, Nazism and Fascism, often mixed with pornographic imagery. The book was printed in Italy, but when it was imported, French customs officers withheld it at the border under the assumption it was Nazi propaganda. Only when one of them pointed out that Willem published in the left-wing Libération did they realize their mistake. Yet this didn't mean the end of the controversy. Many book stores still refused to sell it and instead sent it back to the publisher. It therefore made 'Lust en Strijd' very rare. Willem nevertheless said that he was most proud of this book and 'Romances et Mélodrames' (Éditions du Square, 1977). In 2015 it was eventually reprinted.

With 'Gloire Coloniale et d'Autres Récits Exotiques' (Les Éditions du Square, 1981) Willem delved into Europe's colonial horrors. 'Willem 30/40' (Futuropolis, 1987) focused on the United States. The work tackles the blackest pages in their history: McCarthyism, the Korean War, racism against blacks, the Black Panther Movement, the Kennedy assassinations, the Vietnam War, Watergate, the Iran hostage crisis, Reaganomics...

'Euromania', from the chapter about Italy, mocking Pope John Paul II and his stance on birth control.

In 1984, Édition Moderne published Willem's 'Europa über Alles!' (1984), a book with cartoons about Europe. Five years later, when the Berlin Wall fell, he decided to expand his original concept. The end result, 'Euromania' (1992), was published by both De Harmonie and Futuropolis as a multilingual book in Dutch, English, French and German to coincide with the Treaty of Maastricht and numerous festivities regarding the European Union. 'Euromania' ditches up dirt and sleaze about the post-war history of all 12 European member states. In his trademark merciless style, Willem looks at past horrors like colonial crimes, the DDR, Baader-Meinhof, Northern-Irish terrorism, Action Directe, the Brabant Killers, Thatcherism, the Falklands War and the dictatorships in Spain, Portugal & Greece. But he also pays attention to contemporary problems, such as the mafia, drug trafficking, sex scandals, royal scandals, corporate crime, political assassinations, government corruption, separatism, the ultraconservative Vatican and the rise of the far-right, neo-fascism and neo-Nazism.

'Les Aventures de l'Art'.

With 'Le Feuilleton du Siècle' (Cornelius, 2000), the cartoonist embarked upon his most ambitious project yet. Since a new century waited ahead, he felt it would be a swell idea to look back at the entire scope of the 20th century and all its wars and atrocities. A highlight is a two-page labyrinth showing all 20th-century conflicts as an obstacle people need to survive to reach the end of the century. 'Déguelasse' (2014) looks back at political events of the past 30 years, including wars in the Middle East and Africa, and the Western forces who made them possible. In 2004 Willem published 'Les Aventures de l'Art' (Cornelius, 2004), expanded in 2019 as 'Les Nouvelles Aventures de l'Art' (Cornélius, 2019) and translated into Dutch as 'De Nieuwe Avonturen van de Kunst' (Concerto Books, 2020). The comic book features satirical biopics about famous artists, done in comic strip format and prepublished in Charlie Hebdo. It targets both the snobby art industry as well as specific icons, such as Pablo Picasso, Salvador Dalí, Edward Hopper, Christo, Le Corbusier, Andy Warhol, the Cobra movement and Banksy. Though Willem also sheds light on less famous artists, among them Sophie Calle, Roberto Platé, Gil J. Wolman, Fedele Azari and Nelly van Doesburg. The world of literature, film and music isn't spared either. One comic artist is targeted too: Hergé.

The infamous 1966 swastika cartoon from God, Nederland en Oranje, which got Willem fined in the Netherlands.

Style and controversy

Willem is known for his black-and-white ecoline drawings, rarely making use of color. Since the dawn of his career, they have been criticized for being quite clumsily drawn, especially when copying photographs. Faces and body parts are often out of proportion. His caricatures have been contested for not always resembling their subjects well. Yet he still managed to capture his messages in a few simple lines, something he has in common with another cartoonist, Arend van Dam. However, most criticism of Willem has less to do with his graphic style and more with his subject matter. General audiences are often repulsed and outraged by his cartoons and comics, which are seemingly obsessed with sex and violence. He often depicts politicians and authority figures in pornographic situations and/or scenes of decapitations, bloodshed and disembowelment. Even his love book 'Plus Mort Que Moi Tu Meurs' (Futuropolis), sex manual parody 'Poignées d'Amour' (Cornelius, 1995) and the anally retentive sequel 'Anal Symphonies' (Cornelius, 1996) are devoid of any eroticism. His drawings are so sardonic, shocking and crass that they've led to a massive stream of angry letters, censorship, publication rejections, trials and even death threats. The 1966 Juliana cartoon and its subsequent trial are the most infamous case, but there have been more examples.

On 30 April 1979, drawings from Willem's book 'The Adventures of Prince Bernhard' were refused from an exhibition in Schiedam about comics. Out of protest, Martin Lodewijk pulled back his own work from the expo. On 3 August 1994, the cultural councilor of Ermelo removed a cartoon by Willem from an exhibition titled 'Moord en Doodslag', only a few hours before the event started. The illustration depicted two men, one putting his testicles in the other's bra. On 12 September 2001, only one day after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, Willem drew a cartoon for Libération showing the famous 1972 photograph by Nick Ut of a Vietnamese girl running away from a U.S. napalm bombing during the Vietnam War. In the background he added planes flying into the World Trade Center. Many readers were outraged that the cartoonist implied that the U.S. now suffered some kind of poetic justice.

In April 2005, Willem published a cartoon in Libération depicting Jesus appearing in the sky, while a group of bishops are appalled that their savior is wearing a condom. The newspaper was promptly sued for blasphemy by Agrif, a traditionalist Catholic group led by Front National politician Bernard Anthony. On 30 March 2006, they lost their case and again on 17 May on appeal. A 28 July 2006 cartoon in HP/De Tijd about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict also caused some uproar. It depicts two Israelis building the wall on the West Bank, which unfortunately is shaped like a Nazi concentration camp. Nevertheless, it won the 2006 Inktspotprijs in the Netherlands.

Inktspot Award-winning cartoon, published in HP/De Tijd on 28 July 2006. Translation: "And that's that. Safe borders for Israel." - "It reminds me of something."

So far, Willem has only paid a fine twice for his cartoons. The first time for the aforementioned cartoon about the swastika-shaped police officer, and the second time in 2009, when he illustrated an article for Libération about government minister Roland Dumas who owned illegal money on a Swiss bank account. The politician sued them and won because they couldn't prove their claims sufficiently enough. Overall, Willem has gotten somewhat desensitized by the commotion his work has caused over half a century. He once defended himself in an interview published in Trouw on 16 May 2008: "You don't blame a butcher for selling meat! What I draw is far less worse than what happens in the world on a daily basis." For the same reasons, he doesn't feel bad earning money with other people's misery, because "weapon dealers and industries earn a lot more than I do." In fact: some of his work was inspired by personal traumas. He and his wife once lost a baby in a miscarriage. To their shock, the doctor coldly advised them to just flush the remains of the dead foetus down the toilet. Willem did so, but it motivated him to draw a rather infamous comic strip about flushed down fetuses rising from toilet bowls to act revenge on mankind.

Willem is also a man of principles, who refuses to be assimilated by his targets. When the Institute Néerlandais in Paris asked him for his sponsorship in 2007, he accepted, but warned them that he wouldn't shake the hand of Dutch queen Beatrix if she was present at the reception. He kept his word that evening, staunchly turning his back to her.

Graphic contributions

Willem made contributions to collective comic books, such as 'Nimbus Présente le Grand Orchestre' (Cumulus, 1980), 'Animaux Admis' (Alliance Européenne, 1990) and 'Crème Solaire' (Cornelius, 2002). He illustrated songs by Tachan in the four-volume song collection 'Les Chansons de Tachan' (Dargaud, 1982-1984), to which most established Charlie Hebdo cartoonists made a contribution. He was one of several artists to make drawings for the "safe sex" promotional book 'Les Aventures de Latex' (FortMedia, 1991), the anti-racism special 'Rire Contre Le Racisme' (SOS Racisme, 2006), the anti-Jacques Chirac book 'La Success Story du Président' (Hoëbeke, 2006) and the religious satire book 'Non de Dieux' (Pat à Pan, 2010). Willem joined various Dutch and Flemish cartoonists to make a "chain comic", composed of individually drawn scenes which together form one long comic strip, published as 'Het Lieve Leven' (2000) by Robin Schouten's Incognito.

In February 2009, Willem designed a series of wine labels for the Dutch-Portuguese liquor company Dirk Niepoort and their Douro wine. They were sold under the title 'De Gestolen Fiets'. He collaborated with Edmond Baudoin on the graphic novel 'Jazz à Deux' (Super Loto Éditions, 2015), which offers a look at the jazz festival Jazz à Foix. To conclude, his work has appeared in the 'New Comics Anthology' (Collier Books, 1991) and the 'Small Express Expo' (1997-2004) series of alternative comics, published by the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund.

Book illustrations

Willem illustrated one genuine children's book in his career, 'Van Niks en Nogs Wat' (De Harmonie, 1985), written by Ton de Vreede. The book stars a young boy, Jantje Pilaar, who lives in the village Niks and manages to cure all illnesses. A jealous major, priest and doctor therefore ask him to fulfill three difficult challenges. The work remains a remarkable stylistic break for Willem, though he admitted that he made it at the advice of his publisher and never actually met the author. Later he created illustrations to Daniel Varenne's 'Par La Bande' (Ed. Demoures, 1999), Jo Bertil's 'Les Porcs du Monde' (Le Zouave, 2000) and Jean-Claude Lecocq's 'L'Important C'est La Dose' (Les Apogogistes, 2002).

Written contributions

Willem provided a foreword to 'Weg Met De Varkens: 500 Jaar Opruiend Tekenwerk' (Van Gennep, 1969), a collection of offensive political cartoons from the 15th century until the 20th. He also penned the prologue for a 1977 book collection of comics previously published in Evert Geradts' underground comix magazine Tante Leny Presenteert, as well the foreword to 'Enfantillages' (1999) by Kelek.

In 1980, Willem scripted 'Wat Heb Ik Nou Aan Mijn Fiets Hangen?', illustrated by Joost Swarte and serialized between 26 April and 11 October of that year in Vrij Nederland. The story stars two kids, Rik and Klaartje, who travel the world in their special car. Most of the dialogue features satirical commentary about the countries they visit, but presented in the style of an old-fashioned children's book about exotic adventures. In 1982, it was published in book form as 'De Wereldreis van Rik en Klaartje' (De Harmonie, 1982), with a French translation under the title 'Le Tour du Monde de Ric et Claire' (Futuropolis, 1982) and a German one as 'Klara und Ricky. Eine Reise um die Welt' (Édition Moderne, Zürich, 1983).

Translations

Lesser known is that Willem has occasionally translated Dutch-language comics into French, such as Joost Swarte's 'De Moderne Kunst' (1980, as 'L'Art Moderne'), Wim T. Schippers & Theo van den Boogaard's 'Sjef van Oekel' (1986, as 'Léon-la-Terreur') and Johannes van de Weert's punk comics 'Les Aventures de Red Rat' (Black-Star, Le Monde à L'Envers, 2016). On one occasion he translated S. Clay Wilson's 'Bastard' (Futuropolis, 1984), from English into French.

Photo of Willem.

Media appearances

Willem appeared in Benoît Lamy's 'Cartoon Circus' (1972), a Belgian documentary about cartoons and comics, where he was interviewed alongside Siné, Picha, Roland Topor, Cabu, Jean-Marc Reiser, François Cavanna, Professeur Choron, Gal (Gerard Alsteens), Georges Wolinski, Joke and Jules Feiffer. He voiced the fish-headed character Willem Van Mandarine (a pun on William of Orange) in Henri Xhonneux and Roland Topor's film 'Marquis' (1989). The makers picked him because they needed "someone with a Dutch accent". The picture is nowadays a cult classic. In 1995, he made an animated version of 'Hansel and Gretel' for the 'Il Était Une Fois...' series by Rooster Studio, which featured animated fairy tales designed by famous French comic artists.

Recognition

On 18 December 1989, Willem received the Grand Prix Nationale des Arts Graphiques. In 1996, the Salon International du Dessin de Presse et d'Humour de Saint-Just-le-Martel awarded him the Grand Prix de l' Humour Vache (1996), which meant that he received a real-life cow! The same year his book 'Poignées d'Amour' won the Alph-Art Humour (1996) at the Festival of Angoulême. During the Stripdagen in Den Bosch, on 23 and 24 October 2000, he received the Dutch Stripschapprijs for his entire body of work, and six years later, the Medaille d'Honneur (2006) from the French government. In the Netherlands, he won both the Inktspotprijs (2006, awarded on 16 January 2007) and the Junior Inktspotprijs (2008). In 2013, he won the Grand Prix de la Ville d'Angoulême, being at age 71 the oldest to receive this award since the 76-year old Pellos won it in 1976. Willem was consequently also the first Dutch artist to win this prize. In 2015, he was honored with the Prix International d'Humour Gat-Perich for his entire body of work. On 5 March 2025, he receivd the Grand Prix de l'Académie des Beaux Arts for Graphic Art.

His work has often been exhibited, including at the Centre Pompidou in Paris in 2006.

Legacy and influence

Willem's work was admired by Jaap Vegter, who in issue #47 of Stripschrift said: "Bernhard Holtrop works from a totally different mentality than me. It's incredibly impressive what he makes. Not so much the little men he draws, but more the total composition." Joost Swarte said about him: "By drawing what comes into his mind, he gives other cartoonists more freedom. (...) He shows his colleagues that you don't need to hold yourself back." Other admirers have been Kamagurka, Jean-Louis Lejeune, Erik Meynen, Jean Plantu, Peter Pontiac, Joost Swarte, Marc Verhaegen, Zapiro and writer Rudy Kousbroek.

Since 2012, Willem and his Norwegian wife Medi Brath have lived on the island Groix in front of the coast in Brittany (Bretagne). In 2016, he donated his entire archive to the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris. Willem is additionally a member of Cartooning for Peace. He co-signed a boycott of the Eurovision contest in Tel Aviv in 2019.

Willem, signing at Lambiek on 3 March 2020 (Photo: Boris Kousemaker).

Books and documentaries about Willem

For those interested in Willem's life and career, Volume 6 of 'Les Iconovores' series, 'Willem, Printemps Cannibales' (2017) by Virginia Ennor focuses on him. Pierre-André Sauvageot's documentary 'Het Oog van Willem/L'Oeuil de Willem' (2006) is highly recommended as well. In his prolific and veritable mountain of book publications, the majority difficult to find, Jean-Pierre Faur's anthology 'Deadlines' (1998) and 'Trapenards & Melodramas, Stories 1968-2015' (Cornelius, 2014) are arguably the most beautiful and comprehensive overviews of his work.

Between 17 September and 31 October 1998, Willem exhibited in Kees Kousemaker's Gallery Lambiek under the title 'De Kleurrijke Jaren Tachtig' ('The Colourful 1980s'). He held a book signing in our store on 3 March 2020. Lambiek will always be grateful to Willem for illustrating the letter "R" in our encyclopedia book 'Wordt Vervolgd - Stripleksikon der Lage Landen', published in 1979.