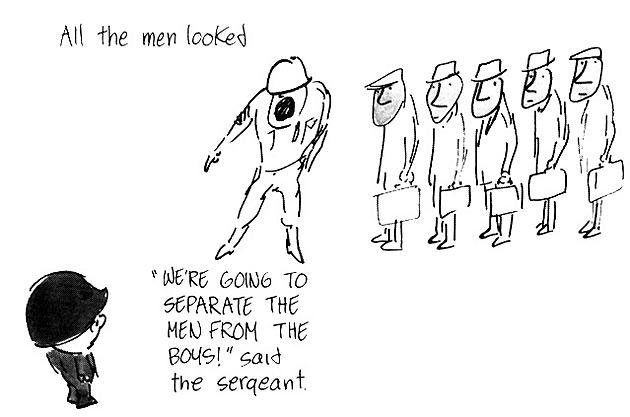

Cartoon starring Feiffer's famous dancer.

Jules Feiffer is widely regarded as one of the most famous and influential American satirists of the 20th century. He started his career co-writing episodes of Will Eisner's 'The Spirit' (1940-1952) and creating his own gag comic 'Clifford' (1949-1951). Feiffer, however, made his strongest impact as an editorial cartoonist. His comic series 'Feiffer' (1956-1997) broke new ground by tackling taboos other cartoonists did not address. He effectively used his comic strip as an editorial column. His characters openly discussed relationships, sex, depression, family troubles, current events and existential angst. Voicing his strong personal opinions about political and social matters through his characters, Feiffer opened doors for many other alternative cartoonists. He also created the satirical graphic novel 'Tantrum' (1979) and the 'Kill My Mother' (2014-2018) trilogy, a pastiche of detective noir. Additionally gaining recognition as an author, playwright and screenwriter, his most enduring children's books are 'Munro' (1959) and 'The Man in the Ceiling' (1993). His play 'Little Murders' (1967) was well received, produced in New York and London, and made into a movie in 1971. Feiffer also wrote the script for the Alan Arkin movie 'Carnal Knowledge' (1971), starring Jack Nicholson, Candice Bergen and Art Garfunkel. With his influential book 'The Great Comic Book Heroes' (1965), Feiffer wrote one of the first essays on superhero comics. Jules Feiffer’s large body of work earned him a strong following among adult readers and many awards, including a 1986 Pulitzer Prize.

Early life and influences

Jules Feiffer was born in 1929 in The Bronx, New York City, the son of an often unemployed salesman. Feiffer's cousin was Roy Cohn, who later became infamous as an accomplice of senator and anti-Communist witch hunter Joseph McCarthy. Feiffer credited his mother for steering his artistic career. She worked as a fashion designer and sold watercolor drawings from door to door. She encouraged her son to draw a lot and supported his studies at the Art Students League of New York. Feiffer was also allowed by his mother to participate in a John Wanamaker art contest, which won him a medal. But in his autobiography, Feiffer also criticized her for being a stereotypical Jewish mother. She complained regularly and was paranoid about expressing controversial opinions in public. Jules was often shamed, making him too inhibited to masturbate, even in his twenties. Suffering from severe mother complexes, it particularly irritated him that he couldn't say what he wanted and was supposed to unquestioningly obey his mother. The frustrated cartoonist spent years in therapy. Many of his cartoons were driven by anger and the determination to discuss taboo topics, including his own personal issues.

From a young age, Feiffer enjoyed reading. Among his literary influences were Nathaniel West, I.F. Stone and Murray Kempton. As a child, he wrote a letter to one of his favorite comic strip artists, Milton Caniff, who sent him an encouraging reply. Among his other notable favorites were Roy Crane, E.C. Segar and Will Eisner, followed by Winsor McCay, Sheldon Mayer, Percy Crosby, Gene Ahern, Crockett Johnson, Raeburn Van Buren, Cliff Sterrett, Walt Kelly, Al Capp, V.T. Hamlin, George Herriman. In terms of single-panel cartoonists, Feiffer looked up to William Steig, Saul Steinberg, André François, George Grosz, Feliks Topolski and Victor Weisz. Later in his career, he also expressed admiration for Art Spiegelman, Ted Rall, Daniel Clowes, Chris Ware, Craig Thompson, Alison Bechdel, David Small, Jeff Danziger, Tony Auth, Pat Oliphant, Tom Toles, Signe Wilkinson and Patrick McDonnell. Feiffer was also mesmerized by Hollywood actor and dancer Fred Astaire, who influenced the iconic female dancer character in his cartoons.

Education

After high school, Feiffer attended the Pratt Institute in 1947 to improve his drawing skills. He left after a year, because he felt there was too much focus on abstract art. A more satisfying experience were the evening classes he attended for three years under Lenny Kusokov, advertising art director for Grey Advertising.

'The Spirit' section of 11 September 1949, featuring Feiffer's breakthrough story 'Ten Minutes' (art by Will Eisner).

The Spirit

In 1946, Feiffer picked up a phone book and looked up the name of comic artist Will Eisner - of whom he was a huge admirer - and applied for a job as cartoonist in his studio. The two got along well and Eisner was amazed how much Feiffer knew about his work. He was equally impressed with Feiffer's enthusiasm about comics. Much like him, he didn't regard it as just a job to pay the bills. Yet Feiffer's artwork was not up to Eisner's standards, so he employed Feiffer as a clean-up artist. Their bond was so strong that Feiffer felt comfortable voicing criticism, for instance about the declining quality of Eisner's signature comic 'The Spirit'. Eisner then challenged his pupil to write a story of his own. Feiffer came up with 'Ten Minutes', a story detailing the final 10 minutes of the life of the failed store robber Freddy.

At the start, readers are informed that the story will actually take "ten minutes to read", and throughout the story, a clock on top of the page counts down the remaining minutes. The story was a remarkable experiment in pacing and timing, something Feiffer had learned from his co-worker Abe Kanegson. Impressed when he proofread 'Ten Minutes', Eisner used the story for the 11 September 1949 issue of his Sunday newspaper supplement The Spirit Section. Eisner particularly liked Feiffer’s ability to write naturalistic dialogue and promoted him to regular writer of episodes for 'The Spirit'. Feiffer did so until 'The Spirit' came to a close on 5 October 1952. Years later, 'Ten Minutes' was adapted into the live action short film 'Will Eisner's the Spirit: Ten Minutes' (1989) by Edgewood Studios, directed by David Giancola.

Clifford

While he was working as a scriptwriter for 'The Spirit', Feiffer once asked Will Eisner for a raise. When his taskmaster refused, Feiffer threatened to quit. As a counter proposal, Eisner offered his assistant the opportunity to create his own comic strip. 'Clifford' (1949-1951), a charming gag series about a little boy and his naïve view of the world, debuted in Eisner's one-shot comic book 'Kewpies' (Spring 1949). For the drawing style, Feiffer tried to imitate Walt Kelly, and in the writing, he aspired to show how children really behave, not how adults want to see them. Between 10 July 1949 and 4 March 1951, 'Clifford' continued in The Spirit Section as a weekly back cover feature. The later episodes of ‘Clifford’ were written by Feiffer and drawn by Gene Bilbrew. Although 'Clifford' didn't leave a lasting mark with readers, it is historically notable for debuting a year before Charles M. Schulz's 'Peanuts' (1950-2000), a comic strip with which it shares thematic similarities. Although it is not known if Schulz had ever read 'Clifford', Will Eisner, in an interview by John Benson for Panels, stated that 'Clifford' was "a great feature that deserves to be recognized as the forerunner of Peanuts." 'Clifford' was Feiffer's first attempt to create comics about real-life people and their worries, a theme that became his trademark.

'Munro'.

Munro

Between January 1951 and 1953, Jules Feiffer was drafted in the U.S. Army. He continued to write new episodes of Will Eisner's 'The Spirit', which were then sent back to the series' regular illustrator Wallace Wood. Feiffer served at the Signal Corps in New Jersey, but never saw combat. Instead he spent most of his time marching and doing pointless drills and tasks. He hated his military service, because he felt treated like a child, again blindly obeying orders. To ventilate his frustrations, Feiffer wrote a satirical children's story in his spare time, 'Munro'. The tale follows a four-year-old boy who is accidentally drafted into the army. Nobody believes him when he tries to argue that he is just a kid.

In hindsight it is amazing that Feiffer actually created this subversive anti-army story at the Civilian Corps Publication Center in Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, with full support of his supervisor, Perc Couse. Seven years later, when Feiffer had become famous, 'Munro' was published in his story collection 'Passionella and Other Stories' (McGraw-Hill, 1959). In the following year, 'Munro' was adapted into an animated short by Gene Deitch, with Feiffer voicing a sergeant. The picture won the 1961 Academy Award for Best Animated Short. Decades later, Deitch directed two other animated shorts scripted by Feiffer, 'Bark, George' (2003), narrated by John Lithgow, and 'I Lost My Bear' (2005), in which Feiffer's daughter Halley provided narration.

Animation scriptwriting

When Jules Feiffer returned to civilian life in 1953, 'The Spirit' had come to an end, so he worked at a variety of jobs before becoming an animation scriptwriter at UPA ('Gerald McBoing Boing', 'Mr. Magoo') and Terrytoons ('Mighty Mouse', 'Heckle & Jeckle'). At Terrytoons, he worked with Gene Deitch for the first time, scripting his 'Tom Terrific' animated shorts and developing a never-produced TV series, 'Easy Winners'. Previously, Feiffer felt insecure about his graphic skills, but the simple, effective artwork of UPA made him realize you didn't necessarily need great art to tell great stories. His time at UPA gave Feiffer more self confidence, and he began trying to sell his cartoons to various magazines.

First Feiffer cartoon published in The Village Voice on 24 October 1956.

Cartoons

When Jules Feiffer debuted as a cartoonist in the mid-1950s, he had a hard time trying to sell his work. Initially every publication rejected them. His cartoons were difficult to pigeonhole. They used a comic strip format, but weren't adventure stories or gags with wacky characters. Instead, they featured common people talking about recognizable everyday issues. Because of their unusual style and content, most editors had no clue how to market them. While his applications always ended in rejections, Feiffer did notice that all these editors had a copy of the alternative weekly newspaper The Village Voice on their desk. He figured that if he was able to get his cartoons printed in this magazine, other editors would notice him soon. Therefore Feiffer focused all his efforts on The Village Voice, even offering to work for free. This was a proposal they couldn't reject and so, on 24 October 1956, Feiffer's comic strip debuted in The Village Voice. Originally titled 'Sick, Sick, Sick', with the subtitle 'A Guide to Non-Confident Living', it later changed to 'Feiffer's Fables' and eventually simply to 'Feiffer'.

While most people wouldn't want to work without payment, Feiffer didn't mind. As an employee for Eisner his pay had also been low, and he still received income as an animation scriptwriter. It also made him more audacious. Since he didn't have to worry about losing income from his non-paying job, Feiffer felt he had nothing to lose, and could draw and say whatever he wanted, even about social taboos.

Feiffer cartoon published in the Detroit Free Press on 23 November 1959.

When Feiffer debuted in 1956, most mainstream media in the USA kept up a facade, portraying only people with happy and carefree lives. Controversies were deliberately swept under the carpet. If they had to be discussed, they were kept vague to avoid offending or disturbing audiences. Especially newspaper comics and cartoons focused on simple, family friendly gags and stories. Feiffer had built up many frustrations over the years. At home, in school and in the army he and everybody else were supposed to never question authority. Nobody was allowed to talk about anything remotedly risqué or upsetting. He was sure that he wasn't the only person who was fed up with these unspoken social taboos. His very first editorial cartoon summarized his feelings perfectly. A man complains that he is literally worried "sick, sick, sick" to his stomach. He summarizes everything that gives him stress, until two other men tell him to "shut up!". But as they leave the scene, they too grab their bellies, obviously as sick as him.

In his cartoons, Feiffer addressed real emotions, down to the darkest feelings, like lovesickness, fear, doubt, anger, sadness and despair. His characters often worry or feel dissatisfied with their lives. Many cartoons deal with relationships. They show people trying to live together as partners, family members or colleagues. Feiffer especially broke new ground by introducing sex as a topic. Although he didn't depict any nudity, his characters do talk about lust and sexual frustrations. At the time this was unexplored territory in most mainstream magazines, except in Hugh Hefner's Playboy.

In a September 2010 interview conducted by Jesse Rhodes for Smithsonian Magazine, Feiffer explained: "Particularly as an American, we are taught - as other cultures do not teach - that failure is a bad thing. It's looked down upon. Don't be a loser. We have all sorts of negative notions about failure and so the hidden message is: 'Don't risk anything. Don't take chances. Be a good boy. Stay within the limits. Stay within the proper boundaries and that way you won't get into trouble and you won't fail.' But of course in the arts and virtually anything else that leads a satisfactory life, failure is implicit. You try things, you fall on your face, you figure out what went wrong, you go back and try them. And what I was hoping to do for the readers (...) - particularly young readers - was tell them that a lot of the good advice they got should simply be ignored."

Feiffer cartoon from 4 September 1978.

Together with Paul Conrad in the L.A. Times, Feiffer was one of the earliest U.S. cartoonists to address the African-American civil rights movement, the Vietnam War and the sexual revolution. While Feiffer criticized conservatism, U.S. Republicans, racism, J. Edgar Hoover, the Cold War and pro-war politics, he was equally critical of left-wing complacency, U.S. Democrats and sexual liberation. He often surprised people by rallying for issues most people wouldn't be bothered about. Between 1961 and 1964, he testified at the obscenity trials against Lenny Bruce, defending the comedian's freedom of speech. At the height of the Watergate affair, Feiffer designed a cover for the Village Voice criticizing the Nixon administration's illegal bombing of Cambodia, which he felt was more tragic than breaking into the Democratic Party Headquarters.

To convey his messages, Feiffer deliberately kept his artwork and lay-outs simple. A typical Feiffer cartoon comprises six to eight borderless panels, which can vary in size and shape. Backgrounds are minimal, and text doesn't appear in speech balloons, but floats above the characters' heads. In a 28 July 2008 interview with Sam Adams for AV Club, he said that he looked at artists like Saul Steinberg, William Steig, André François and George Grosz. During the first decade he drew with pointed wooden dowels to stand out among the competition, then changed to pen and ink. In his quest for spontaneity he drew directly on the paper without any penciling. Using photocopy machines, Feiffer could reduce his drawings, cut them out and put them into a lay-out. Even though the process took longer, it did give him more vital drawings. In the previously mentioned interview with the AV Club, Feiffer added: "I discovered over and over again that once you lose control, you have a chance of getting good at it. And once you're controlling the work, it's not going to be very good, or it won't be as good as it should be."

Characters

Feiffer's cartoons don't have many recurring characters. The most recognizable duo are the brainless womanizer Huey and his timid sidekick Bernard, who often discuss sex and relationships. His most iconic individual character is "The Dancer", an unnamed female ballerina in a black leotard. The Dancer often holds a monologue about a current affair, a specific feeling or to welcome "a new season". She expresses these topics through an interpretative dance. The Dancer was inspired by Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers musicals. Feiffer also often attended stage performances by modern dance companies. It struck him that the dancers expressed all their emotions in movement. By letting his Dancer character "dance" about a topic, it made his cartoons more visually interesting. It was also far more fun to draw than characters just standing around.

Cartoons: success

Jules Feiffer's cartoons quickly caught on, reaching a wide audience. Many readers were surprised to read such deep, thought-provoking themes in a simple comic strip. His comics read more like an illustrated editorial column. He caught the attention of intellectuals, striking a particular chord with young adults. Feiffer perfectly fitted the changing, free-spirited mood of the 1960s and 1970s. He voiced what many people felt and thought, but were too scared to say out loud. In an era when most U.S. citizens had an unshaken faith in their government, institutions and the American way of life, he dared to tackle complex issues and express strong progressive opinions. Yet Feiffer was modest about it: "At the time liberals didn't understand that they had First Amendment rights."

Once his cartoons were in higher demand, Feiffer was in a better position to ask for payment. In 1962, Hugh Hefner, chief editor of Playboy, became the first to pay for his work, prompting The Village Voice to do the same. Playboy ran his 'Bernard and Huey' cartoons under the title 'Bernard Mergendeiler'. He always preferred these two magazines, because they gave him the most creative freedom. Hefner did occasionally suggest changes to his cartoons, but only with the goal to make Feiffer's arguments stronger. Soon Feiffer was syndicated nationally by the Robert Hall Syndicate and later by Universal Press to newspapers like the Boston Globe, Minneapolis Star Tribune, Newark Star-Ledger and Long Island Press. His cartoons appeared in The Nation, Playboy, Esquire, Mademoiselle, Holiday, Life, Commentary, Saturday Evening Post, Ramparts, The Los Angeles Times and The New Yorker, as well as the London Observer in the UK and Vrij Nederland in the Netherlands. A book compilation, 'Sick Sick Sick: A Guide to Non-Confident Living' (McGraw-Hill, 1958, reprinted in 1992 by Fantagraphics), became a bestseller.

Media adaptations

Film director Stanley Kubrick once considered adapting Jules Feiffer's cartoons into a film and asked him to write an original screenplay, as well as the script for 'Dr. Strangelove'. Feiffer liked Kubrick's work, but was aware that the perfectionist director would likely dictate him what to do, rather than collaborate. Feiffer declined both offers. 'Dr. Strangelove' was eventually written by Terry Southern, author of 'Candy' and 'The Magic Christian'. Decades later, Judy Dennis directed the short 'The Dancer Films: Nine Minutes' (2011), in which Andrea Weber played Feiffer's dancer. Seven years later, Dan Mirvish made 'Bernard and Huey' (2018), a live-action film based on Feiffer cartoons. The picture won various awards, including the Grand Jury Prize (2017) at the Guam International Film Festival, "Best Screenplay" (2017) at the Manchester Film Festival and "Best Film from the American Continent" (2017) at the Jaipur International Film Festival.

Illustration

Early in his career, Feiffer considered becoming a children's book illustrator, but after reading Maurice Sendak he felt so intimidated that he dropped the idea. But eventually, in 1961, Feiffer made illustrations for a children's book by his roommate, Norton Juster. Both men shared an apartment in Brooklyn Heights, but had no prior experience in the field. Juster merely started writing for fun, while Feiffer created images, taking inspiration from the illustrators John Tenniel, Edward Ardizzone and Gustave Doré to give his illustrations a more elaborate style than his cartoons. The book, 'The Phantom Tollbooth' (1961), follows a young boy who travels to the Kingdom of Wisdom through a magic tollbooth. There he tries to restore the shattered country through adventures that help him appreciate learning things. A clever story full of amusing puns, 'The Phantom Tollbooth' is also a metaphor for the value of wonder and education to appreciate life. The book became an unexpected bestseller and was translated into many languages. In 1969, it was adapted into an animated feature film by Chuck Jones. Years later, Feiffer illustrated another children's book by Juster, 'The Odious Ogre' (2010). This book revolves around a giant ogre who terrorizes the country, until he meets a friendly young lady who helps him out in an unpredictable way.

Tantrum

In 1979, Feiffer drew his first graphic novel 'Tantrum' (Alfred A. Knopf, 1979), only a year after Will Eisner's 'A Contract with God' popularized the genre. The story originally ran in the Village Voice for four weeks, after which Feiffer decided to turn it into a full-fledged comic book. 'Tantrum' features a 42-year old man who suffers from a midlife crisis. In an emotional moment, he transforms himself to become a two-year old boy again. This gives him the freedom to do whatever he wants, without shame or repercussions. But while he enjoys life much more than before, he also discovers the disadvantages of acting like an infant. The clever satirical metaphor was praised by many critics, including Will Eisner and Neil Gaiman, who called it one of the finest graphic novels ever published. Stylistically, 'Tantrum' is more in line with Feiffer's cartoons and book illustrations than with other graphic novels. Everything was drawn without preliminary sketching and most panels are just one drawing spread over an entire page.

Kill My Mother

Over three decades later, Feiffer wanted to make an ambitious and realistic comic story, paying homage to the detective pulp stories he enjoyed in his youth. However, since this required elaborate graphic skills, detailed backgrounds as well as historical research, he was unsure whether he could pull it off. He hired an assistant, who eventually pulled back from the project. This motivated Feiffer to just draw everything himself after all. He watched and recorded old films on the TV channel Turner Classic Movies, so he could freeze frame certain scenes to sketch them down on paper. Feiffer used inventive lay-outs to make his narrative more engaging. Buildings, cars, clothing and airplanes were especially difficult for him to draw, making each page a challenge. The end result, 'Kill My Mother' (Liveright, 2014), is a hard-boiled mystery romance about a detective and his girlfriend, combined with a subplot about teenagers trying to get by during the Great Depression. The work reads like a pastiche of detective noir, but is also an enjoyable and intriguingly solid, complex thriller in its own right. 'Kill My Mother' won the Eisner Award for “Best New Graphic Album” and was praised by comic legends like Art Spiegelman, Chris Ware and Stan Lee. Two sequels followed, 'Cousin Joseph' (Liveright, 2016) and 'The Ghost Script' (Liveright, 2018), continuing the storyline throughout the McCarthy era in the late 1940s and 1950s.

Novels and children's books

Jules Feiffer’s first written novel was 'Harry the Rat with Women' (1963), about a narcissistic man who is too in love with himself to pay any attention to other partners. Despite this, many people admire him, inspiring him to start a political movement. His second and final novel, 'Ackroyd' (1977), starts as a parody of detective fiction. A private investigator delves deep into the life of a writer, until he starts to take over his personality, bringing up questions about the detective's own identity. Feiffer's first children's book, 'The Man in the Ceiling' (1993), revolves around a young boy who wants to become a comic writer, but is discouraged by his father and own feelings of self doubt. A more popular boy helps him out, until an unexpected obstacle reaches their path. 'The Man in the Ceiling' received good reviews and in 2017, Feiffer worked with Andrew Lippa to adapt it into a musical. In 1999, Feiffer released his children's picture book 'Bark George', about a puppy who does not sound like a puppy should, despite the efforts of his mother to help him.

The Great Comic Book Heroes

As a non-fiction author, Feiffer is renowned in comic circles for 'The Great Comic Book Heroes' (Bonanza Books, Dial Press, 1965), which he wrote in collaboration with E.L. Doctorow. The work was one of the first academic studies of comics, focusing on the superhero genre. Feiffer provides a personal history of the medium, starting off in 1937 until the early 1950s. He discusses various series and explains their appeal to him, and also offers a historical context and artistic analysis. In his innovative book, Feiffer discusses comics in the same way a critic would analyze the work of a novelist or a graphic artist. He also addresses common criticisms heard about comics, particularly in the light of the 1950s witch hunts by Dr. Fredric Wertham. In the famous closing chapter, he argues whether comics are "junk" or not. He points out that even junk can be good, because comics do deliver escapist entertainment, which is why people read them in the first place, much like any light-weight novel. He stated, "Comics are junk, but that junk is good, even necessary."

'The Great Comic Book Heroes' was an instant bestseller. People who previously dismissed the comic medium as low-brow pulp now looked at it with different eyes. Many series and cartoonists from the past were rediscovered, including Will Eisner's 'The Spirit', which enjoyed a veritable revival. In 2003, 'The Great Comic Book Heroes' was reprinted by Fantagraphics. A monologue about Superman, held by David Carradine in Quentin Tarantino's film 'Kill Bill, Vol. 2' (2004), was directly based on theories from Feiffer's book.

Cover of 'The Great Comic Book Heroes'.

Plays

In 1959, Jules Feiffer designed the poster for the short-lived play 'The Nervous Set'. Later in his career, he himself became an accomplished author of satirical plays, movie screenplays and TV scripts. Most were written for quick cash, without the assumption that they might ever be produced. Nevertheless, some of his titles were adapted. 'Little Murders' (1967) is an odd play about a woman, Patsy, who falls in love with Alfred, an asocial man who is so passive that he is indifferent towards pain. Alfred isn't alone, as most people in their city feel apathetic about other people's suffering. Patsy's family turns out to be even more eccentric. Feiffer wrote 'Little Murders' after the assassination of President Kennedy. The play closed quickly on Broadway, but was a surprise hit at the Aldwych Theatre in London. A 1969 off-Broadway revival won an Obie Award. In 1971, 'Little Murders' was adapted into a film by Alan Arkin, starring Elliott Gould and Marcia Rodd in the title roles. The black comedy was well received by critics. Comic artist Dave Sim later based the Judge in his comic series 'Cerebus the Aardvark' on Judge Stern in this picture.

'Feiffer's People' (1969) is a play consisting of 32 humorous vignettes, based on characters and situations from his cartoons. Most are people trying to find their place in life, only to find out the world doesn't care. 'Knock Knock' (1976) takes place in a log cabin, where a matter-of-fact former stockbroker, Abe, and romantic unemployed musician, Cohn, have lived together for ages. They discuss their varied viewpoints when Joan of Arc visits them and tries to help them reconsider their lives before going to Heaven. 'Grown Ups' (1981) was written after Feiffer's mother passed away. Jake, a successful reporter, is commissioned to interview Henry Kissinger, former U.S. Secretary of State. While his Jewish parents are ecstatic about the idea, Jake suddenly has conflicted feelings about having lived his entire life up to the expectations of his family. A similar kind of angst is found in 'Elliot Loves' (1989), where two lovers have found the ideal partner in each other, but are terrified and uncertain what this will bring them. When Eliot introduces his partner to his friends, they are confronted with themselves.

Film and TV scripts

Out of all Feiffer's film scripts, 'Carnal Knowledge' (1971) is the best known. The film was directed by Mike Nichols, whom Feiffer knew from his comedy sketches with Elaine May. Feiffer always felt the comedy duo’s humor was similar to the spirit of his own cartoons and was glad when Nichols adapted his work. 'Carnal Knowledge' revolves around a callous womanizer (Jack Nicholson), his more well-behaved roommate (Art Garfunkel) and their equally opinionated girlfriend (Candice Bergen). The film follows the changing dynamic in their relationship from their college years until their forties. 'Carnal Knowledge' received good reviews and is nowadays considered a cult classic. Feiffer additionally wrote the screenplay for Robert Altman's 'Popeye' (1980), because Richard Sylbert, who was also the production designer on 'Carnal Knowledge', felt Feiffer was "the only one who could make these characters real." Yet Feiffer only agreed to write the screenplay if they took E.C. Segar's original comics as reference point, instead of the animated cartoons. The film was shot on the isle of Malta, with Robin Williams and Shelley Duvall giving very convincing portrayals of Popeye and Olive Oil. Nevertheless the film didn't do well at the box office. Stan Hart and Mort Drucker ridiculed it in comic strip version as 'Flopeye', published in issue #225 (September 1981) of Mad Magazine.

Feiffer additionally wrote the script for Alain Resnais' film 'I Want to Go Home' (1989), about the life of a has-been cartoonist in Paris. Despite the fact that Resnais spoke little English and Feiffer little French, the picture got made and received good reviews. The prolific scriptwriter also wrote the animated short 'Boomtown' (1985) by Bill Plympton, which satirized the Cold War. Feiffer scripted two 1984 episodes of the TV series 'Comedy Zone', the 1985 episode 'Puss in Boots' of 'Faerie Tale Theatre' and a 1991 episode of 'The Nudnik Show', based on Kim Deitch's cartoon character. Feiffer also created the drawings for the episode 'Three Is Enough' (2008) of 'The Naked Brothers Band'.

Feiffer cartoon from 1998.

Media appearances

Over the years, Jules Feiffer has been a regular interviewee in documentaries and TV series about comics, cartoonists and comedy. In 1972, he appeared in Benoît Lamy's documentary 'Cartoon Circus', a Belgian documentary about cartoons and comics, in which he was interviewed alongside Siné, Picha, Roland Topor, Cabu, Jean-Marc Reiser, François Cavanna, Professeur Choron, Gal (Gerard Alsteens), Georges Wolinski, Willem and Joke. He was also interviewed in Robert Heath's ‘Hugh Hefner: Once Upon a Time’ (1992), Susan Warms Dryfoos' 'The Line King: The Al Hirschfeld Story' (1996), Michael Letcher’s 'God's Will' (2000) about preacher Will D. Campbell, Andrew D. Cooke's documentary 'Will Eisner: Portrait of a Sequential Artist' (2007), Brad Bernstein's documentary about Tomi Ungerer, 'Far Out Isn't Far Enough' (2012), Josh Melrod and Tara Wray's 'Cartoon College' (2012), about The Center for Cartoon Studies and their annual education of amateur cartoonists, and Michael Stevens' 'Herblock: The Black & the White' (2013) about political cartoonist Herblock. The artist appeared in the documentary series 'The First Amendment Project: No Joking' (2004), 'Funny Already: A History of Jewish Comedy' (2004), 'The Jewish Americans' (2008), 'A Broadway Lullaby' (2012) and 'Superheroes: A Never-Ending Battle' (2013), Bob Hercules and Rita Coburn Whack's documentary 'Maya Angelou: And Still I Rise' (2016). He also appeared as a cartoonist in a 2006 episode of the TV series 'Horizon'.

Graphic and written contributions

Feiffer contributed to Françoise Mouly and Art Spiegelman's 'Little Lit', namely 'Little Lit: Strange Stories for Strange Kids' (2001). He also wrote the chapter about E.C. Segar in 'Masters of American Comics' (Yale University Press, 2005), a catalog book by John Carlin, Paul Karasik and Brian Walker to an exhibition in the Hammer Museum and Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. Feiffer also provided the foreword to Nicole Hollander's 'The Sylvia Chronicles: 30 Years of Graphic Misbehavior from Reagan to Obama' (2010).

Recognition

Feiffer won a George Polk Award (1961), a Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Cartooning (1986), an Inkpot Award (1988), the Milton Caniff Lifetime Achievement Award (2004), the Creativity Foundation's Laureate (2006) and Writers Guild of America Lifetime Achievement Award (2010). The animated short 'Munro', based on his work, received the 1961 Academy Award for Best Animated Short. His play 'Little Murders' won an Obie Award (1969), and 'The White House Murder Case' won an Outer Circle Critics Award (1970). His graphic novel 'Kill My Mother' won an Eisner Award for "Best New Graphic Album". In 1996, he was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters (1996) and eight years later, the Eisner Award Comic Book Hall of Fame (2004).

Final years and death

In addition to writing and cartooning, Feiffer was active as a professor at Yale School of Drama, Northwestern University, Dartmouth College and Stony Brook Southampton. In 1997, Feiffer quit The Village Voice over a salary dispute. He went to the New York Times where he continued a similar monthly comic strip until 18 June 2000. He started to grow tired of coming up with new material every week and the final four episodes had him talk with his iconic dancer about the loss of her venue. In April 2008, The Village Voice approached him, asking what it would take to get him back to do a cartoon about Hilary Clinton. Feiffer asked for a large sum and a full color page, and got his wishes.

Between 1988 and 2006, Fantagraphics released four volumes of 'Feiffer: The Collected Works', a collection initially projected as a fifteen-volume compilation series of Feiffer's complete comics work. In 1996, he donated his papers and artwork to the Library of Congress. In 2008, he wrote a furious letter of complaint to the New York Review of Books, after they criticized a new book by cartoonist David Levine.

His oldest daughter Kate Feiffer wrote a children's book, 'Which Puppy?' (2009), for which Jules Feiffer made the illustrations. His middle daughter Halley Feiffer is an actress and playwright.

On 17 January 2025, Jules Feiffer passed away of congestive heart failure at his home in Richfiield Springs, New York, at age 95.

Legacy and influence

Film director Stanley Kubrick admired Feiffer's "scenic structure (...) and the eminently speakable and funny dialogue" of his comics, which were "close to my heart." Rock composer Frank Zappa cited Jules Feiffer in the liner notes of his album 'Freak Out!' (1966) as one of the people "who made our music what it is". He was the only cartoonist on that list. Film director and comedian Woody Allen's type of Jewish comedy borrowed overtones from Feiffer's cartoons, to the point that the cartoonist himself noticed. Feiffer: "It's hard to believe that Woody Allen could have gotten that early character of his without having read about Bernard Mergendeiler. Now we know it's not Woody at all - he didn't draw it from his own character, he drew it from mine." Allen once mentioned that, as a teenager, he was attracted to a type of woman (long hair, black leotards) "almost what you'd call a Jules Feiffer type of girl." The front cover of Feiffer's book 'Sick, Sick, Sick' is also shown in the animated opening credits of the film 'Grease' (1978), along other nostalgic things from the 1950s.

Jules Feiffer had a strong impact on alternative cartoonists, especially in tackling taboo subject matter. In the United States, he influenced Derf Backderf, Lynda Barry, Matt Groening, Stuart Hample, Paul Karasik, Peter Kuper, Edward Sorel, Art Spiegelman, Ann Telnaes, Tom Toles, Tom Tomorrow, Garry Trudeau and Chris Ware. He also inspired artists in Argentina (Copi), Belgium (Gerard Alsteens (Gal)), France (Blutch, Claire Bretécher, Wolinski), Italy (Guido Crepax) and South Africa (Zapiro).

Books about Jules Feiffer

For those interested in Feiffer's life and career, his autobiography, 'Backing into Forward: A Memoir' (University of Chicago Press, 2010), is a must-read. An insightful addition is Martha Fay's 'Out of Line: The Art of Jules Feiffer' (Abrams, 2015), which has a foreword by film director Mike Nichols.