'Agrippine'.

Claire Bretécher was one of the foremost socio-satirical French cartoonists of her generation. Her sharp and subtle observations of the prosperous, urban female of the 1970s and 1980s made her world famous, as her work was also published in most of the other European countries and the USA. Bretécher was a pioneer in many ways. During the 1960s, she was the first female comic artist with a prominent spot in several Franco-Belgian comic magazines. Her humorous series for Record ('Baratine et Molgaga' ), Tintin ('Hector') and Spirou ('Les Gnangnan', 'Les Naufragés') already hinted at the irony and humor of her later work. She was also at the vanguard of a new wave of adult-oriented comics with her contributions to Pilote and as co-founder of the satirical magazine L'Écho des Savanes. Bretécher was additionally one of the first comic artists to successfully venture into self-publishing. But most of all, she was the first satirist who meticulously and subtly captured the behavior and conversations of both the adult and adolescent female in her two signature series 'Les Frustrés' (1973-1981) and 'Agrippine' (1988-2009), all in her trademark loose and sketchy style.

Early life and career

Claire Bretécher was born in 1940 in Nantes into a middle-class Catholic family as daughter of a jurist and a housewife. Her father was a violent man, and her mother always stimulated her daughter to pursue autonomy and independence. Bretécher took these life lessons to heart throughout her career. As a child, she read magazines for girls, like La Semaine de Suzette, but also the comic magazines Tintin and Spirou. Drawing her own comics since childhood, she however dropped this generally considered inferior art form while studying at the Academy of Fine Arts in Nantes, where abstract art was the norm. After her education, she settled in the Parisian Montmartre neighborhood around 1959. She worked as a babysitter and as a high school drawing teacher, but desired a career working for the press. Bretécher saw her first drawings published in Le Pèlerin magazine, and then contributed illustrations more frequently to the magazines of Bayard Presse. By the second half of the 1960s, she also worked for the publishers Larousse and Hachette, and for advertisers. While her early graphical inspirations were Franco-Belgian authors such as Hergé, André Franquin and Will, the sketchy linework of her later, more satirical comics revealed the influences of Brant Parker and Johnny Hart's 'Wizard of Id', Charles M. Schulz's 'Peanuts' and the socio-satirical work of Jean Bosc, Jules Feiffer and James Thurber.

'Baratine et Molgaga' (published in the Netherlands as 'Nitsotov en Netsochek'). Dutch-language version.

Early comics

In 1964, Bretécher's art style was still in a formative state when she drew her first comic story for Pierre Dac's humorous magazine L'Os à Moelle. Written by René Goscinny, 'Facteur Rhésus' was a humorous strip about a mailman. In a late 1970s interview with Jean-Pierre Mercier, Bretécher recalled Goscinny's script required all sorts of things she couldn't draw, like cars. The project was therefore quickly aborted, and Bretécher decided to focus on what she could do best, drawing humans. From 1964 on, she made her modest debut in the monthly Record with cartoons, illustrations and gag pages, often featuring the characters 'Claire et Pétronille' (1966-1970). Between 1968 and 1970, she made 'Baratine et Molgaga' (1968-1970), a humorous comic series about the quirks of a medieval Hun prince and his benevolent jester. In 1965, she was also present in Tintin with the largely pantomime gags of the unfortunate adolescent 'Hector' (1965-1966).

'Les Gnangnan' in Spirou #1671 (1970). The boy tells the girl that she told a lot of lies about him, but his mother told him to forgive his enemies. Yet, he "doesn't agree with his mum."

Les Gnangnan

By 1967, Bretécher joined Spirou, where publisher Charles Dupuis personally greenlighted her project about a gang of kids, called 'Les Gnangnan' (1967-1970). Remarkable, since Bretécher's strip deviated heavily from the magazine's traditional humor style. It was inspired by the subtle humor of Charles M. Schulz' 'Peanuts', had dialogues written in cursive script and portrayed young kids conversing and philosophizing in adult speech. While her further Spirou comics were comparable to other humor comics of that time period, 'Les Gnangnan' already forebode Bretécher's later, more personal work.

Les Naufragés

Bretécher's second feature for Spirou was the gag strip 'Les Naufragés' (1968-1971), one of the first series written by Raoul Cauvin. While their career paths eventually moved into completely different directions, Bretécher and Cauvin were a perfect match in terms of cynical humor. The series stars the crew of a sunken ship, swimming in the open sea in search of rescue. Most of the humor lay in the interactions between the captain and the naïve sailor who caused all the mayhem.

Robin les Foies

Claire Bretécher additionally made four short stories of 'Robin les Foies' (1969-1971), a medieval comic full of intentional anachronisms. Robin is a detective, tasked with protecting his demanding king from usurpers, crooks and other opponents. He is however also lazy and doesn't care about his job.

'Fernand l'Orphelin' (Le Trombone Illustré, 26 May 1977).

Alfred de Wees / Fernand L'Orphélin

Claire Bretécher's role in Spirou came to an end shortly after the discharge of editor-in-chief Yvan Delporte and the arrival of his successor, Thierry Martens. Delporte was however a big fan of Bretécher (and her work), and asked her to work with him on a new comic for the Dutch comic magazine Pep. The duo made five short stories of 'Alfred de Wees' ('Fernand l'Orphelin', 1971-1972), another cynical humor comic, this time about an opportunistic and self-pitying orphan boy. It was Bretécher's sole production made directly for a foreign market, and the stories weren't published in French until they appeared in Delporte's Spirou supplement Le Trombone Illustré in 1977.

Cellulite - 'Les Bonnes Oeuvres' (Pilote #581, 1970).

Pilote

While still working for the juvenile press, Claire Bretécher began her association with the comic magazine Pilote, which had more mature content. 'Cellulite' (1969-1977) was her first creation with a predominantly adult tone and humor. Just like her previous comics 'Baratine et Molgaga' and 'Robin Les Foies', she chose a medieval setting. Her protagonist, Cellulite, became one of the first female anti-heroines of Franco-Belgian comics. Cellulite is a princess, tired of waiting for her Prince Charming. Her father is a busy king, who not only devotes his time to exploit his subjects, but also looks for a suitable husband for his daughter. A difficult task, since Cellulite is not particularly a natural beauty, to put it mildly. She is however very emancipated for the time period, and actively protests against her father's choices, while pursuing her own interests.

Bretécher also contributed several short stories and gags to Pilote, most based on her own scripts. While chief editor René Goscinny gave her artistic freedom, she was assigned to do some other tasks. Bretécher, for instance, helped out Hubuc, who was terminally ill, with the second episode of the historical humor comic 'Tulipe et Minibus' (1970). She however severely detested working on the magazine's "current affairs" pages, the so-called "actualités", to which all Pilote's authors were expected to contribute. As a pastime, she began making her own 'Salades de Saison' (1971-1974), gag pages with social observations, which were a direct predecessor to 'Les Frustrés'.

Cover illustrations for Pilote #674 (1972) and the first issue of L'Écho des Savanes (May 1972).

L'Écho des Savanes

In the early 1970s, part of Pilote's authors team revolted against the editorial policies of René Goscinny. Nikita Mandryka was one of the instigators and decided to launch his own magazine. Bretécher tagged along with her good friend Gotlib, even though she continued to work for Pilote as well until 1977. The trio each made 16 pages, which formed the first issue of L'Écho des Savanes, published in May 1972. The team personally took care of the production, printing and distribution. Bretécher utterly hated going to bookstores, convincing them to carry the new magazine, only to get kicked out. Mandryka was however perfectly in his element and invested in more initiatives. The original DIY approach of L'Écho des Savanes lasted ten issues. Bretécher and Gotlib bailed out in fear of losing their money. Gotlib moved on to launch his own magazine, Fluide Glacial, while Claire Bretécher made her mark in the leftist press. Launched in the wake of the U.S. underground comix movement and the French satirical publications Hara-Kiri and Charlie-Hebdo, L'Écho des Savanes called in a new era of autonomously published comic magazines. Magazines like Fluide Glacial (1975- ), Métal Hurlant (1975-1987) and Psikopat (1982-2019) offered their authors artistic freedom, and stayed clear from the conservative editorial policies of the traditional press.

'Beauté Mon Beau Souci' (L'Écho des Savanes #8, July 1974).

Leftist press

Following her adventure with L'Écho des Savanes, Claire Bretécher broke out of the comics market and began working for the general press. Her first excursion was the comic series 'Les Amours Écologiques du Bolot Occidental' (1973), which debuted in the first issue of the ecological monthly Le Sauvage in May 1973. The comic stars a sex-obsessed dog, who desperately tries to be admitted into a reserve for animals in danger of extinction. On 24 September 1973, Bretécher made her debut in the societal section 'Notre Époque' of the leftist-oriented news magazine Le Nouvel Observateur. Throughout the following decades, she subtly and painfully exposed the urban, prosperous female in all its fashions and hypocrisies, starting with her weekly feature 'La Page des Frustrés' (1973-1981).

Les Frustrés

'Les Frustrés' (1973-1981) debuted on 15 October 1973 in Le Nouvel Observateur. It had no recurring characters, but instead presented archetypes: housewives, career women, mothers, feminists, college students... All deal with universal everyday problems, such as despair, loneliness, anxiety and the need to be liked, but also more recognizable female issues, such as menstruation, the pill, weight concerns, raising children, dealing with men who just don't seem to understand, rivalry with other women and aging. Men, if present at all, are mere side characters. 'Les Frustrés' effectively satirized the May 1968 generation, whose ideals weren't always compromisable with everyday life, and who throughout the bleak 1970s evolved into materialistic yuppies by the time the 1980s rolled along. Bretécher worked in a sketchy, minimalist style. Most of her pages feature white or dark backgrounds, with usually only couches, beds, chairs, tables or walls as recurring props. Dialogue is the real focus. Although her comics are presented as gag comics, they don't rely on punchlines. Most episodes are mere anecdotic moments in life or reflections on society. They are often witty, but some are melancholic, embarrassing or confrontational as well. Bretécher's humor lies in the spot-on satire of the language and mannerisms of the bourgeois intellectual, while the drawings reveal the bored snobbism and decadence with subtle nuances.

Bretécher eventually quit 'Les Frustrés' in 1981, when she felt the times had changed to such a degree that the original concept of her comic strip was no longer contemporary. It was a typical product of the faith in progress during the 1960s and 1970s, which a decade later seemed to have vanished away in society. Instead, she began to focus on other satirical comics.

Self-publishing

In 1972-1973, Éditions Dargaud had released two albums with Bretécher's comics for Pilote, 'Cellulite' and 'Salades de Saison'. Le Nouvel Observateur on the other hand had no experience with book collections. The individualist author had no interest in dealing with the paternalism of a traditional publishing house, and decided to do it all herself. Her first collection of 'Les Frustrés' appeared in 1975 and was an instant bestseller. Bretécher was the first Franco-Belgian author who actually made good money from self-publishing. She also syndicated her comics to foreign publishers. 'Les Frustrés' eventually appeared in books and magazines from the United States (in Viva and National Lampoon), the United Kingdom (as 'Frustration'), the Netherlands (as 'De Gefrustreerden' in Gummi and Opzij), Spain (as 'Los Frustrados' in Totem), Portugal (as 'Os Frustrados'), Germany (as 'Die Frustrierten'), Italy (as 'I Frustrati' in Linus, Alter Alter), Norway (as 'De Frustrerte'), Denmark (as 'De Frustrerede'), Sweden (as 'De Frusterade'), Finland (as 'Turha Joukko') and Croatia, among other countries. Meanwhile, Jacques Glénat published her earlier comics for Spirou and Record in book format in 1976-1977, while Bretécher herself collected her comics for L'Écho des Savanes in the book 'Le Cordon Infernal' (1976). Claire Bretécher continued self-publishing her works, in later years under the Hyphen imprint, until she sold the publishing rights of her back catalog to Dargaud in 2006.

Book covers for 'Les Amours Ecologiques du Bolot Occidental' and 'La Vie Passionée de Thérese d'Avila'.

One-shot thematic comics

In 1979, Le Nouvel Observateur published Bretécher's humorous and alternative view on the life story of the Spanish Catholic saint Teresa of Ávila. 'La Vie Passionnée de Thérèse d'Avila' (1979) aroused many readers' protests who deemed it blasphemous, while Bretécher also received support from prominent Catholics and theologians.

In 1981, Bretécher ended her weekly page in Le Nouvel Observateur which continued to prepublish her later thematic observations of contemporary society, often counting one or two pages in length. In 'Les Mères' (1982), she commented on motherhood and family planning. This was also the subject of 'Le Destin de Monique' (1983), about an actress who becomes pregnant just when she lands her first major role. She asks her Portuguese cleaning lady Candida to become the child's surrogate mother, but several twists and turns will affect the eventual fate of the fetus. The two books about 'Docteur Ventouse, Bobologue' (1985-1986) offered a humorous look on a medical practice, while 'Tourista' (1989) mocked the decadent holidays of the Parisian middle-class. Finally, 'Mouler Démouler' (1996) offered more observations in the style of 'Les Frustrés'.

Agrippine

Most of Bretécher's output after 1988 was however devoted to one character, the rebellious adolescent 'Agrippine' (1988-2009). The reader follows Agrippine at the top of her teenage crisis, struggling with existential dilemmas and curiosities. She is a typical spoiled teenager, who cannot be bothered with future plans, but instead is angry with everyone and everything. She resents her parents for not divorcing when she was a child, and is annoyed with her baby brother and his "pee poo" humor. Again, Bretécher offered observations of the generation gap between babyboom parents and the bored and spoiled teenagers of the 1990s. Bretécher self-published seven volumes until 2004, with one final installment released by Dargaud in 2009. The absolute best-seller in the series was 'Agrippine et l'Ancêtre' (1998), in which Agrippine's forgetful but also quite modern great-grandmother is introduced. She retired from comics with the final 'Agrippine' album in 2009.

Other activities

In addition to comics, Bretécher continued to work as an illustrator for books, magazines and posters. She co-wrote two theatrical plays, 'Frissons Sur Le Secteur' (1975, with Serge Ganzl and Dominique Lavanant) and 'Auguste Premier où Masculin-Féminin' (1980, with Hather Robb). She was also an accomplished painter, specializing in close-up watercolor portraits. Her paintings have been collected in art books and catalogs like 'Portraits' (Denoël, 1983), 'Moments de Lassitude' (Hyphen, 1999), 'Portraits Sentimentaux' (La Martinière, 2004), 'Claire Bretécher: Dessins et Peintures' (Éditions du Chêne, 2011) and 'Le Tarot Divinatoire de Claire Bretécher' (Éditions du Chêne, 2011).

Recognition

In 1975, the year of her first self-published book, Claire Bretécher was awarded the "Prize for Best Scenario" at the Angoulême International Comics Festival. At the 29-31 January 1982 edition of that same festival, she was offered the prestigious Grand Prix Lifetime Achievement Award. Bretécher was the first female comic author to receive this honor, and kept this unique position until Florence Cestac (2000) and Rumiko Takahashi (2019) won the prize as well. Her album 'Agrippine et l'Ancêtre' earned her Angoulême's Alph-Art Humor prize in 1999. Her oeuvre was praised in other countries too. In 1987, she received the Swedish Adamson Award for her entire body of work. In Germany, her influential comics were celebrated with the Max & Moritz Prize in 2016. She was additionally praised by intellectuals like Pierre Bourdieu, Roland Barthes, Umberto Eco and Daniel Arasse. The French linguist Barthes even labeled her "Best Sociologist of the Year" in 1976. The astronomist Jean-Claude Merlin named an asteroid after her in 2006.

Media adaptations

Bretécher's work has seen adaptations for animation, stage and radio. Eleven animated shorts based on 'Les Frustrés' were released in 1975. 'Agrippine' was adapted by Frank Vibert and Nicolas Mercier into a 26-episode animated TV series for Canal+ in 2001. New animated shorts based on both series were produced by Christèle Wurmser and Christine Bernard-Sugy between 2012 and 2014.

Feminism

Bretécher was often pigeonholed as a "feminist" cartoonist, but she downplayed this label. Even though she sympathized with the feminist ideals, she was strongly opposed to the militant aspects of it. In interviews she explained that she didn't make comics about women to express a feminist statement, but mostly because "I understand women better than men." While her comics often address the battle of the sexes, female inequality and the women's liberation movement, Bretécher satirized these matters too. Some self-declared feminists in her cartoons are mere poseurs. Others are whiny and/or hypocritical. Again others are well-meaning, but have unrealistic goals. Bretécher felt many feminists in the 1970s were too dogmatic in their beliefs, which often led to desperate attempts to not conform to gender stereotypes. An irresistible target for her satire. One thing that Bretécher did achieve was paving the way for more female authors in the male-dominated comic industry. In the late 1960s, she was the first female cartoonist with a regular spot in several classic comic magazines. Bretécher always pointed out that she never felt out of place or victim of misogynist behavior, though. With her spot-on observations of contemporary society, she became a true media personality, with regular TV appearances and international exposure.

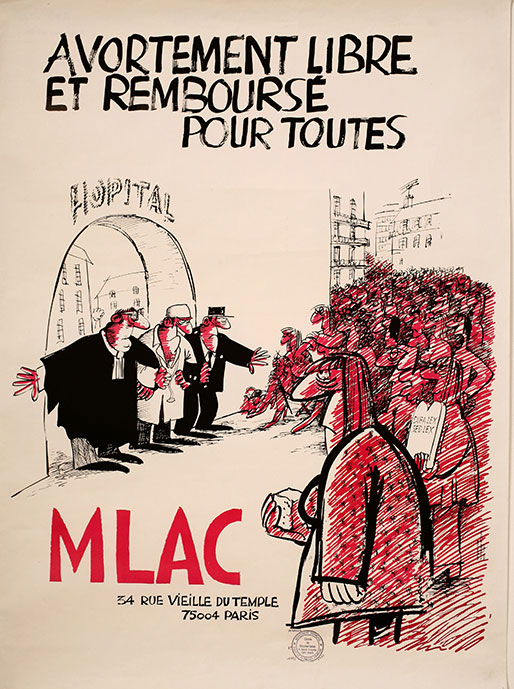

Poster for the MLAC women's movement in France (1973).

Influence

Claire Bretécher inspired a new generation of female comic authors to follow their own career paths and create personal work. Chantal Montellier, Florence Cestac, Nicole Claveloux and Annie Goetzinger also established themselves as respected and prominent authors in their home country. Since the generation of Bretécher, the French-speaking countries have seen many important female authors, for instance Marjane Satrapi, Pénélope Bagieu, Lisa Mandel, Julie Maroh, Catherine Meurisse, Isabelle Pralong, Aude Picault, PrincessH, Coco, Bénédicte and many more. The Argentinian Maitena Burundarena and the French cartoonist Hélène Bruller have specifically named her as an important inspiration, while Catel, Penelope Bagieu, Frédéric Jannin, Françoise Mouly and Blutch have also expressed their admiration.

In terms of subtle social satire, Claire Bretécher was a forerunner as well. Of course it is difficult to pinpoint whether she was a real instigator or a mere product of her time. Internationally, one can recognize influences of Bretécher in the work of the German cartoonist Ralf König. In the Netherlands, Gerrit de Jager and Jaap Vegter are prime examples of similar chroniclers of society. Other Dutch artists who named Claire Bretécher an influence on their work have been Danny Steggerda and Mirjam Vissers. In Belgium, Bretécher inspired Jean-Louis Lejeune and Katrien Van Schuylenbergh. In the United States, Nicole Hollander named Bretécher as one of her strong influences.

'Agrippine'.

Final years and death

Retired from self-publishing, other publishers have released collections of her back catalog since 2006. Glénat compiled her early humor comics in the volume 'Décollage Délicat' (2006), while Dargaud has issued compilations like 'Inédits' (2007) and 'Petits Travers' (2018). Claire Bretécher passed away in Paris on 10 February 2020, two months before her 80th birthday.

Self-portrait, made for the comics news magazine Schtroumpf in 1974.