Tomi Ungerer was a French cartoonist, poster designer, sculptor, children's book writer and illustrator who gained cult status in the 1960s. He is best remembered for illustrating Hayo Freitag's classic children's book 'Die Drei Räuber' ('The Three Robbers', 1961) and Jeff Brown's 'Flat Stanley's Worldwide Adventures' (1964). In his own books he often expressed satirical commentary and daring, taboo-breaking imagery, regardless whether he wrote for children or adults. Among mature readers he is infamous for his provocative anti-establishment cartoons and S&M-themed erotic drawings. His anti-war and anti-racism posters are iconic images of the counterculture movement. Ungerer's work has always been controversial and for a long while his books were banned in the U.S. and U.K.. Therefore he is nowadays more obscure in these countries, but elsewhere in the world still regarded as one of the finest and foremost artists of his era. Ungerer received countless awards and honors throughout his career, among them his own museum.

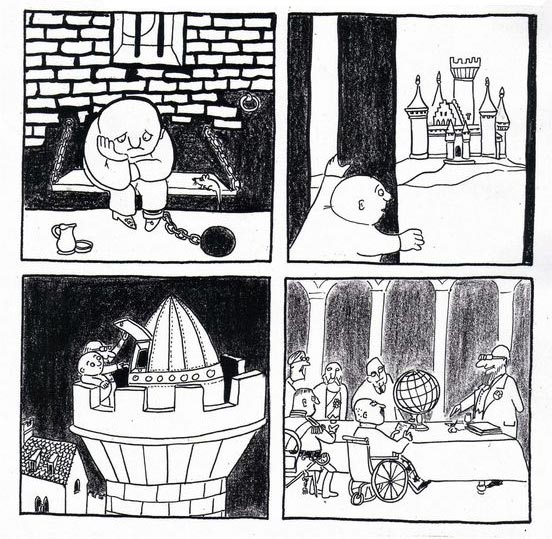

From: 'Underground Sketchbook'.

Early life

Jean-Thomas ("Tomi") Ungerer was born in 1931 in Strasbourg, Alsace, France, a region historically known for its large German-speaking population. As a result, he was fluent in both French and German. His grandfather was Auguste Théodore Ungerer, co-founder of the French clockmaking company Horlogerie Ungerer. August Théodore's son, Theodore Ungerer, continued the family business. Tomi Ungerer often observed his father constructing clocks and inherited his creative spark. One of his lifelong hobbies was creating toy airplanes. As a child, Ungerer read The New Yorker and ranked Saul Steinberg, Wilhelm Busch, Gustave Doré, Samivel, Benjamin Rabier, Louis Forton, Edward Lear, James Thurber, Walt Disney, Hergé, André François, Matthias Grünewald and Honoré Daumier among his graphic influences. Later in life he also expressed admiration for Robert Crumb. In 1968, Crumb would quote Ungerer's praise of his work on the back cover of 'Head Comix' (1968). While Ungerer enjoyed comics as a child, he always preferred text comics, where the text is written underneath the images, because "speech balloons ruined the drawings."

Ungerer's youth was marked by many frightening experiences. At age two he cracked his skull by running too fast and making a painful fall. He survived, but was always convinced that he suffered some kind of brain damage. When the boy was four years old, his father passed away from blood poisoning. Ungerer's mother remarried with the head of Spinnerei Haussman's technical department. In 1940, World War II broke out and Hitler occupied France. The Haussman factory became a prison camp, while a Wehrmacht officer came to live in Ungerer's home. Hitler wanted to eliminate anything non-German in the Alsace region. All Jewish citizens were forced to leave and later deported by the Vichy regime to concentration camps. French teachers at Ungerer's school were fired and replaced by German ones. Since Tomi's first name was "too German", teachers now called him "Hans". All pupils were forced to join the Hitlerjugend and were no longer allowed to speak French. They were encouraged to betray anybody who did something anti-German or anti-Nazi, even their family members. Teachers subjected their pupils to Nazi propaganda. Ungerer recalled that one of his first assignments was to "draw a Jew", according to the stereotypical way they were portrayed in Nazi propaganda.

Childhood drawing by Tomi Ungerer from 1943, published in 'A La Guerre Comme à la Guerre'.

Naturally, Ungerer felt frustrated over this unjust situation. He expressed his feelings in a personal diary and several satirical drawings and paintings, which he hid away. His mother managed to protect him whenever he got in trouble. At night, mother and son snuck out to sabotage the roads with pieces of glass, so Gestapo and SS cars couldn't drive through. In 1945, the Allied Forces liberated the Alsace. Ungerer personally witnessed the Battle of Colmar. While he certainly applauded the Liberation, it was still a disillusion. The U.S. troops had little respect or interest for the locals. Some of them plundered buildings and took away two jam pots his family had saved all those years. During the occupation anything French or Alsacien had been suspect, but now everything German had to be banned. Ungerer saw how people burned several German books, which made him realize how absurd life actually was. Half a century later, Ungerer made his childhood diary and artworks available in his autobiographical book 'A La Guerre Comme à la Guerre' (1991). The book also includes memorabilia from the time period, including school books, leaflets, lyric sheets, posters and stamps. It was later translated into German as 'Die Gedanken Sind Frei' (1993) and in English as 'Tomi: A Childhood Under the Nazis' (2002).

His wartime experiences gave Ungerer lifelong recurring nightmares and a strong distrust of authority. He described himself as a realist. Ungerer didn't believe in illusions and always read between the lines. His motto was: "Don't hope, cope." The Nazi brainwashing that scarred his mind as a child taught him a lot. He used the same shock effects in his political posters, because "the best way to fight your enemies is to use their own weapons." Even in his children's books, he didn't mind disturbing young readers with frightening imagery.

Traveling years

In 1951, Ungerer barely graduated from high school, mostly because he rebelled against the pro-French policy and suppression of anything Alsacien. His teacher described him as a "willfully perverse and subversive individualist". Ungerer started biking and hitchhiking throughout Europe, eventually joining the Méharistes (French Camel Corps) in Algeria, back when it still was a French colony. In 1954, he took up studying again at the École Municipale des Arts Décoratifs in Strasbourg, but by lack of discipline he was asked to leave the school again. Ungerer therefore worked as a window decorator and publicity maker for small enterprises.

Children's books

In 1956, Ungerer moved to New York City, motivated by his love for jazz and the work of Saul Steinberg and James Thurber. He went to every children's book publisher with his portfolio, but was rejected because his drawings weren't considered suitable for the target audience. He was advised to visit Ursula Nordstrom of Harper & Row. She was his final option, because the young artist only had 65 dollars left and was in desperate need for food and medical attention. In the hospital he was even refused treatment, since he couldn't afford it. At first, Nordstrom was ready to reject his book, but when he started crying and told her about his dire situation, she took pity on him and published his first book.

The Mellops Go Flying

Ungerer's debut as a children's author, 'The Mellops Go Flying' (Harper & Row, 1957), became an instant bestseller and won him his first award. Ungerer made a deal with the Swiss publishing company Diogenes Verlag, so the book could be translated in Europe too. 'The Mellops Go Flying' stars a family of pigs who go flying, nearly die during their flight, but eventually return home safely. Despite its dark content, it spawned four sequels: 'Mellops Go Diving for Treasure' (1957), 'The Mellops Strike Oil' (1958), 'Christmas Eve at the Mellops' (1960) and 'Mellops Go Spelunking' (1963).

'The Beast of Monsieur Racine' (1971).

The Three Robbers

Over the years, Ungerer published several notable children's books. In Continental Europe, his drawings for Hayo Freitag's 'Die Drei Räuber' ('The Three Robbers', 1961) are arguably his best known work. The story features three highway men who rob coaches and terrorize the country. Everyone is afraid of them, but one night they rob a carriage with a little orphan girl inside. She is too young to know what robbers are and thus not afraid of them. The startled thieves therefore take her to their cave, where she manages to make them change their lives for the better. The look of the robbers was inspired by a 1870 picture story from Münchener Bilderbogen, illustrated by Kaspar Braun.

'The Three Robbers' is nowadays a classic and was adapted into an animated feature twice. In 1972 by Gene Deitch, and in 2007 by Freitag himself, with Ungerer providing the narration. This latter version won several awards at European film festivals. On 28 March 2016, original artwork of a first-print edition of 'Die Drei Räuber' was auctioned in Hotel Drouot for the unexpected sum of 72,724 euros (82,150 dollars).

Flat Stanley

In 1964, Ungerer illustrated 'Flat Stanley', a children's book by Jeff Brown. The story features a young boy, Stanley Lambchop, who is crushed in his sleep by a bulletin board. He survives, but is now completely flattened. Stanley discovers he is able to use his handicapped body for new purposes, such as sliding underneath doors, acting as a kite and mailing himself by envelope. The book became a classic and received several sequels, though Ungerer had nothing to do with them. In 1995, a Canadian teacher, Dale Hubert, launched the Flat Stanley Project, organized all over the world, with people in several continents photographing themselves with a cut-out Stanley doll. Over the years, various celebrities have participated with the project and had their photo taken carrying this cut-out, among them boxing legend Muhammad Ali, Hollywood actors Arnold Schwarzenegger and Clint Eastwood, TV host Steve Irwin, TV cooks Jamie Olivier and Gordon Ramsay, musicians Clay Aiken and Willie Nelson and U.S. Presidents Bill Clinton, George Bush Jr. and Barack Obama. The project was even satirized in the episode 'How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Alamo' (2004) of Mike Judge's animated series 'King of the Hill'.

The Moon Man

Ungerer's best-known personally written and illustrated children's book is 'Der Mondmann ('The Moon Man', 'Jean de Lune', 1966). The story features the Man from the Moon traveling to Earth, where he discovers he's not welcome. People discriminate and eventually jail him, because he's different. Luckily he turns from a "full moon" into a "half moon", which makes him slim enough to escape and return home. The novel was adapted into a 2012 animated film by Stephan Schesch and Sarah Clara Weber, with Ungerer providing narration.

Sequence from 'Jean de la Lune'.

Style

Ungerer was known for his dark children's stories. All throughout history, adults had told their offspring scary stories. Many children's book authors and illustrators had continued this path, with Heinrich Hoffmann's 'Der Struwwelpeter' (1845) as perhaps the most nightmarish example. But by the mid-20th century most children's book publishers avoided anything remotely inappropriate or scary. It wasn't until the 1960s before Ungerer and Maurice Sendak - gained notoriety by publishing children's books with much darker content again. 'The Three Robbers' is bathed in dark, flat colors, with cloaked armed robbers roaming the woods at night. In 'Criktor' (1958), Ungerer made the protagonist a snake, an animal most children's book publishers discouraged authors from using. In 'La Grosse Bête de Monsieur Racine' (1971), the attentive reader can spot many strange details, among them a beggar with reddish eyes who has a chopped off foot in his knapsack. In 'Pas de Baiser Pour Maman' ('No Kisses For Mother', 1973), a schoolyard with smoking and fighting children is depicted. The same story also features a young kitten smoking a cigar and drinking schnapps at breakfast. The most controversial children's book by Ungerer is 'Otto, Autobiography of a Teddy Bear', 1999). The story follows a teddy bear during World War II. He belongs to a Jewish boy, but his family is deported by the Nazis. The Jewish child gives the bear to a German boy. The bear experiences a series of horrible events, such as bombings and warfare, but everything has a happy end.

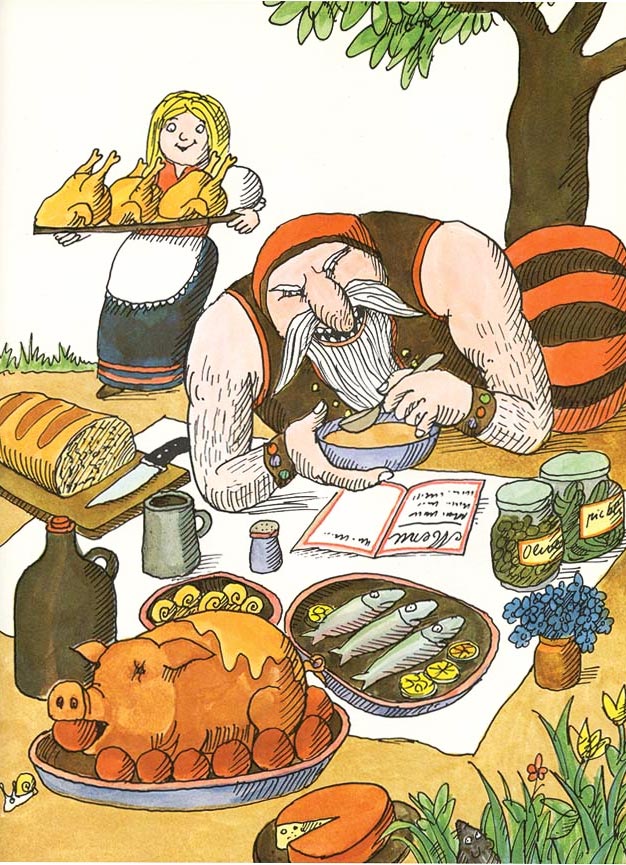

From: 'Zeralda's Ogre' (1967), about a little girl who becomes friends with an ogre.

Ungerer felt that children shouldn't be shielded from horrible or scary things. As a child, he was taught to overcome his fears, which made him stronger as a result. His brother sometimes took him to the cemetery at night where he dressed him in a sheet and told him to play ghost. After that experience he was no longer scared of ghosts. The child protagonists in his novels are never scared either. Characters who would normally frighten people (robbers, beggars, octopuses, rats, snakes...), turn out to have a good side as well. The happy ends to all his children's stories help young readers to overcome their fears and prejudices. One of Ungerer's most famous quotes is: "You have to vaccinate children against evil with cruelty." As for his somewhat subversive and at times odd drawings, he stated that "curiosity" is vital. "The finest gift you can give your children is a magnifying glass, so with a little effort they can make their own discoveries." On the same token, he also liked to use colorful, vocabulary enriching nouns like "a daisy" and a "blunderbus", instead of just "a flower" and a "gun".

Ungerer's work is also notable for its loose and fluid lines. He tended to avoid erasing so they could remain spontaneous. If he drew a wrong line, he simply started all over again until he got it right.

'Kiss for Peace', anti-war cartoon by Tomi Ungerer, 1960s.

Political-social posters

During the 1960s, Ungerer was particularly notable for his posters against racism, nuclear threats and the Vietnam War. One of his most iconic designs of this era is 'Black Power/White Power' (1967), a topsy-turvy drawing of a white and black man devouring themselves. Another well-known poster, 'Join the Free and Fat Society', depicts a nude obese Statue of Liberty whose underwear is the Stars 'n' Stripes. 'Kiss for Peace' shows a U.S. soldier forcing a Vietnamese to lick Lady Liberty's behind. Ungerer's decade-defining posters were later made available in 'The Poster Art of Tom Ungerer' (Darien House, 1971), while his political cartoons are collected in the book 'In Extremis' (Cadesseines, 2018).

Cartoons

Ungerer gained notoriety through his books for adults as well. His 'Underground Sketchbook' ('Pensées Secrètes', 1964), features shocking, macabre imagery, while 'The Party' (1966) offers satirical depictions of fancy-dressed gentlemen and ladies at society meetings. Many of his drawings show beau monde with grotesque faces, make-up and costumes. After paging through a copy of the glossy magazine The Hamptons, Ungerer was utterly disgusted with the shallowness of this world. In an interview with The Comics Journal (issue #303, June 2018), he claimed he never went to a party again afterwards. He did once ring the doorbell at a fancy party, but only to spray the proprietor with a water hose and then run away.

From: 'Underground Sketchbook'.

Erotica

In 1969, Ungerer released a book with explicit satirical erotic drawings: 'Fornicon' (1969). This launched a stream of erotic cartoon books, such as 'Der Sexmaniak' (1971), 'Adam & Eva' (1974), 'Totempole' (1976), 'Babylon' (1979), 'Das Kamasutra der Frösche' ('The Kama Sutra of Frogs', 1982) and 'Guardian Angels of Hell' (1986). Many people were outraged over the explicit and disturbing erotic S&M images. 'Fornicon' was banned in the UK, just like 'Guardian Angels of Hell', which featured drawings of dominatrix at a brothel in Hamburg, whom he personally interviewed about their profession. In March 1985, an exhibition of his erotic art opened in the Royal Festival Hall in London, but after three days a group of feminist activists led by Valerie Wise invaded the exhibition and wrecked the show with spray-paint. In the end, one-third of the exhibition had to be sheltered. Ungerer's erotic books also caused controversy in the United States, where many people couldn't reconcile this with the fact that he was also a well-known children's novelist.

Most critics failed to see the satirical context. Ungerer exaggerated sexual submission and power play by making the erotic imagery severely degrading and violent. A book like 'The Kama Sutra of Frogs' was just a silly series of erotic scenes featuring funny frogs. The artist defended his work: "I'm a satirist. When people take it literally, it becomes something else." He also pointed out that most buyers of his erotic books were women. In fact, famous feminist Gloria Steinem actually liked his work. In regard to his erotic art, Ungerer was interviewed in the documentary 'Eroticon' (1971) by Richard Franklin, alongside other people like Al Goldstein (publisher of the adult magazine Screw) and porn actor Harry Reems ('Deep Throat'). Ungerer's erotic drawings are collected in the book 'Erotoscope' (Taschen, 2001).

From: 'Fornicon'

Controversy

Ungerer's career took off in the USA, where he counted novelists like Saul Bellow, Philip Roth and Tom Wolfe among his friends. Yet he never felt quite at home. It shocked him that the same nation that helped defeat the Nazis and Fascists during World War II was still segregating black people. Ungerer also made himself unpopular through his outspoken political posters and explicit erotica. The University of Columbia refused to exhibit his anti-Vietnam War posters. The editorial building of Ramparts magazine, in which Ungerer posted, was once raided by far-right people who tore up all his drawings. Even the FBI once apprehended him at the New York railway station. He was "suspicious", since he once played poker with the Cuban ambassador and wanted to travel to China as a journalist. In 1960, three men tried to kidnap Ungerer at Idlewild Airport (nowadays JFK), checked his luggage and even his footwear, but let him free again afterwards. He later discovered his telephone was tapped. Ungerer also looked like a fish out of water. Because of his beard and long hair, he was often refused drinks in bars. Ungerer countered people who thought he was a hippie by showing them a penny, pointing at president Lincoln's beard and asking if they would refuse him service as well.

Since Ungerer's adult works were provocative, quite a number of people made the incorrect assumption that his children's books were also "depraved". He once appeared on a talk show, where the head of a Swiss kindergarten network expressed her strong disapproval of his work. She stated that as long as she was in charge, his books would never be allowed in her schools. Funny enough, Ungerer would go on to design a kindergarten later in his career, albeit in Wolfsartsweier, Germany. Since 2002 toddlers can play in a cat-shaped playground there.

But his undeserved reputation stuck. In 1969, during a conference at the American Library Association, he was again criticized for his "dirty" cartoons. Tired of these prudent remarks, he yelled: "If people didn't fuck, there wouldn't be any children, and without children, you would be out of work." In the still very conservative parts of the United States and United Kingdom, Ungerer now became persona non grata. Many bookstores and libraries banned his work and deliberately didn't reprint his books. In 1970, Ungerer therefore left the United States and donated his manuscripts to the Children's Literature Research Collection at the Free Library of Philadelphia. His move and the bans had the unfortunate side effect that he was soon forgotten in the English-speaking world, while remaining a well-known author and artist in Continental Europe.

Move to Canada and Ireland

In 1970, Ungerer moved to Rockport, Nova Scotia in Canada, where he earned a living as a pig farmer and welder. He enjoyed this agrarian lifestyle, but disliked the conservative local community. Religious fundamentalists were so strict that there were no pubs. So local rednecks just bought their alcohol from stores, drank it at home and started gun fights and arson afterwards. By 1976, Ungerer and his family had enough and moved to Ireland, where he would stay for the rest of his life. He combined his artistic career with running his own farm. He owned pigs, 18 cows and more than 600 sheep! In a 17 May 2016 interview for Die Welt, conducted by Dagmar von Taube, Ungerer said that he was once struck by lightning while living in Ireland. He picked up the phone at home during a thunderstorm, when he suddenly got struck by a lightning bolt and his phone melted in his ear. He was lucky that he was still wearing rubber boots - as he just entered his house - and that he stood still without touching anything, causing the voltage to escape.

Graphic and other artistic contributions

Ungerer's success led to more work in the graphic sector. His cartoons appeared in magazines like Esquire, Harper's Bazaar, Life, the New York Times, Ramparts, Newsweek and The Village Voice. In 1966, he became the food column editor in Hugh Hefner's Playboy. He was one of many famous illustrators to make a contribution to Alan Aldridge's 'The Beatles Illustrated Lyrics' (1969) book. Ungerer designed film posters for Stanley Kubrick's 'Dr. Strangelove' (1964), the rock documentary 'Monterey Pop' (1968) and Ken Loach's 'The Angels' Share' (2012).

Ungerer kept drawing for various causes, like animal rights, environmental issues, the Red Cross, Amnesty International, Doctors Without Borders and the Council of Europe. He was a member of the think tank Forum Carolus, which focused on Strasbourgian issues. Ungerer also supported French-German relations and promoted Alsacien culture. In 1972, he designed election posters for German chancellor Willy Brandt who indeed got re-elected. Ungerer also made drawings for AIDS and cancer awareness. He designed an image of a naked girl with a condom-shaped butterfly net to be printed on 500,000 condoms. On 20 January 1992, Ungerer's sister died in an airplane disaster when the plane crashed in the Vosges Mountains, which motivated him to establish the Entraide de la Catastrophe des Hauteurs de Sainte-Odile (Echo), a special aid for the survivors of this particular catastrophe. In 2015, after the terrorist attack on the Charlie Hebdo office in Paris, Ungerer was one of many cartoonists who paid tribute to the victims. He drew a crucified image of Lady Liberty.

In 1988, Ungerer sculpted the "Fountain of Janus" at the Broglie square in Strasbourg, not far from the Opéra National du Rhin. On 15 September 2007 the artist designed a toilet building in Plochingen, Germany. He was one of the interviewees in the documentary series 'Fascism' (1996), about national tendencies in modern-day countries such as Italy, France and ex-Yugoslavia.

Recognition

Throughout his career, Ungerer received many awards, such as the Critics' Award (1967) (1972) at the Festival of Juvenile Literature in Bologna, the Bretzel d'Or (1980), Prix Burckhardt (1983) and Grand Prix National des Arts Graphiques (1995). He won Lifetime Achievement Awards like the Hans Christian Award (1998), E.O. Plauen Award (2005), Berlin Academy Award (2008) and the Society of Illustrators Lifetime Achievement Award (2011). In 2004 the veteran artist was honored with a Lifetime Achievement prize during the Sexual Freedom Awards. In 1999, he was celebrated with the European Prize for Culture and in 2003 the European Council named him Ambassador for Childhood and Education. In 2008, Ungerer received the Prix-Franco-Allemand du Journalisme (French-German Journalistic Prize) for his entire career.

Ungerer was honored as a Chevalier (1990), Officer (2001) and Commandeur (2017) in the Légion d'Honneur. In 1984, the legend was named Commandeur de l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, in 2004, a Chevalier des Palmes Académiques and in 2013 a Commandeur de l'Ordre National du Mérite. Germany showed its respect through the Bundesverdienstkreuz (1993) and the Technological Institute of Karlsruhe granted him an honorary doctorate in 2004.

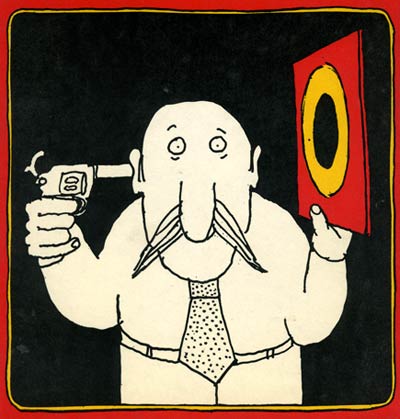

Cartoon by Tomi Ungerer.

Final years, death, legacy and influence

Since the 2000s, Ungerer coped with cancer and several heart attacks. The legendary author eventually passed away in 2019 at the age of 87. In France, he was an influence on Charles Berberian, while in Germany he ranks Jakob Hinrichs and Horst Jansen among his followers. Ungerer also inspired artists in Australia (Bjenny Montero), Belgium (Gal (Gerard Alsteens), Philippe Geluck, Joke, Jean-Louis Lejeune), The Netherlands (Sieb Posthuma), United Kingdom (Roy Raymonde) and the U.S. (Dave Cooper, Maurice Sendak). Ungerer's nieces, Anne and Isabelle Wilsdorf, later became well-known illustrators in their own right.

Books, documentaries and museums about Tomi Ungerer

In 1991, Ungerer published his autobiography, with special focus on his childhood: 'Tomi: A Childhood Under The Nazis'. For those interested in the rest of his life and career, the book 'Tomi Ungerer Incognito' (2015) by Philipp Keel is highly recommended. This book was the museum catalog for the exhibition 'Incognito' about his work, which ran in Kunsthaus Zürich between 30 October 2015 and 7 February 2016 and Museum Folkwang Essen between 18 March and 15 May 2016. Brad Bernstein's documentary 'Far Out Isn't Far Enough: The Tomi Ungerer Story' (2012) features contributions by Maurice Sendak and Jules Feiffer. In 2013 the picture won "Best Documentary" at respectively the Jameson Dublin International Film Festival, the Durban International Film Festival, the Nashville Film Festival, Florida Film Festival, Warsaw International Film Festival.

Since 2 November 2007, Tomi Ungerer also has his own museum, Musée Tomi Ungerer/ Centre International de l'Illustration, in his birth town of Strasbourg. Apart from his own work, the building exhibits works by Saul Steinberg, Ronald Searle and André François.