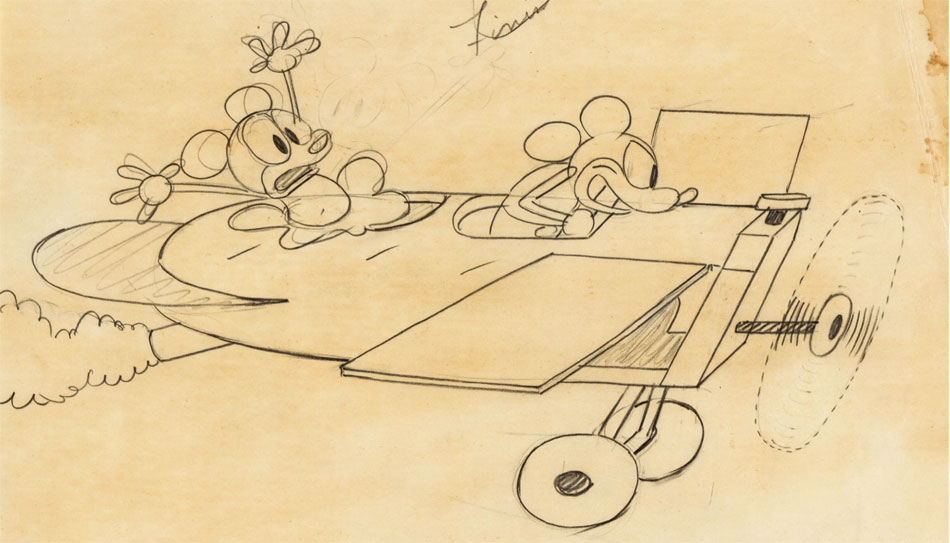

Opening from 'Lost On A Desert Island' (13 January 1930), Mickey's first comic strip appearance. © Disney.

Ub Iwerks was a legendary American animator, famous for his work with Walt Disney. He is credited as co-creator of the world's most famous cartoon character, 'Mickey Mouse' (1928). Within the franchise, he also graphically created enduring side characters, like Minnie Mouse, (Peg-leg) Pete, Horace Horsecollar and Clarabelle Cow. As Disney's loyal companion during his early years of struggle, he helped lay the foundations of the Disney empire. As the first person to draw a 'Mickey Mouse' comic strip (1930), Iwerks is also the first official Disney comics artist in history. However, his career in comics was brief; it lasted only a month. Between 1930 and 1936, Iwerks tried to establish his own animation studio. Lack of success brought him back to the Disney Studios in 1940, where he spent the rest of his career as a special effects expert. Many of his technical contributions have been important to the history of both live-action cinema and animation. Thanks to his dynamic style and ability to work quickly and efficiently, Ub Iwerks has become an animation legend.

Early life and career

Ubbe Eert Iwwerks was born in 1901 in Kansas City as the son of a barber, who later worked as a studio photographer. His father Eert Ubbe was a German immigrant, who had moved to the United States at age 14, coming from the East Frisian town Uttum. Since the Netherlands also have a province named Frisia, it is often incorrectly stated that Iwerks was of Dutch descent. Although the 1940 U.S. Federal Census lists that both of Ub's parents came from The Netherlands, in fact his father's family was Prussian, while his mother's family came from Indiana. From an early age, young Ub showed a gift for drawing. Iwerks' father left the family when Ub was a teenager, after which the boy was forced to drop out of school and get a job to help his family survive.

Meeting Walt Disney

In 1919, Ub Iwerks and Walt Disney first met, while working for the Pesmen-Rubin Commercial Art Studio in Kansas City. Both men had a lot in common. They were born in the same year, with Disney being nine months younger than Iwerks. Both had bad relationships with their fathers, and shared a fascination for animation. In 1919, they founded their own animation studio, Iwerks-Disney Commercial Artists. Disney put Iwerks' name first, since he felt "Disney-Iwerks" would give the wrong impression that they were selling eyeglasses. Their business went bankrupt within a month. In 1920, they joined the Kansas City Film Ad Company, where Hugh Harman, Fred Harman and Friz Freleng were among their colleagues. After hours, Iwerks and Disney studied animation - still a young and crude medium at that time - while making their own cartoon shorts.

'Oswald the Lucky Rabbit'. © Disney.

Laugh-O-Gram

By 28 June 1921, Disney and Iwerks felt confident enough to leave the company and have another try at their own animation studio, calling it the "Laugh-O-Gram Studio". They employed Hugh Harman, Friz Freleng and Carmen Maxwell, animators they had met at the Kansas City Film Ad Company. Another early collaborator was Marion T. Ross. Disney was ambitious and had many ideas for cartoons. Inspired by Terrytoons' 'Aesop's Fables' series, Laugh-O-Gram also created animated shorts loosely based on well-known stories that were in the public domain. Instead of fables, Disney and Iwerks chose fairy tales. However, on 16 October 1923, their enterprise was declared bankrupt again. Disney left Kansas City and moved to Los Angeles, where his uncle Robert and brother Roy lived.

Alice Comedies

With financial aid from his brother Roy Disney, Walt Disney established a new cartoon series, which he named the 'Alice Comedies' (1923). The series was bought by Winkler Pictures, run by Margaret Winkler and her partner Charles Mintz. Loosely based on the Lewis Carroll novels 'Alice in Wonderland' and 'Alice Through The Looking Glass', the shorts featured the live-action adventures of Alice, initially played by the young Virginia Davis, in an animated world. The combination of live-action with animation wasn't new, but their effort was successful enough to be developed into a series. The 'Alice Comedies' (1923-1927) were Walt Disney's first modest commercial hit. It allowed him to reorganize his studio. By 1926, Disney quit working as an artist to focus exclusively on production and story development. Iwerks became his main animator. By dividing the tasks, each man could do what he was best at. Iwerks was such a fine draftsman and fast worker that he did most of the work in the cartoons single handedly. As a cartoon sidekick for Alice, Iwerks created his first recurring character, Julius the Cat. His design was clearly based on Pat Sullivan and Otto Messmer's 'Felix the Cat'. In the cartoon 'Alice Solves the Puzzle' (1925), he created another cat, who became Disney's first enduring character: the villain (Peg-Leg) Pete.

Advertising art from The Film Daily Year Book 1929. © Disney.

Oswald the Lucky Rabbit

In 1927, the 'Alice' series came to an end, and Iwerks designed a new cartoon character, 'Oswald the Lucky Rabbit'. Once again, the rabbit had a design and personality similar to Pat Sullivan and Otto Messmer's 'Felix the Cat'. For a while, Oswald lived up to his name, bringing the company luck. The 'Oswald' cartoons did well with audiences and Disney wanted to improve the technical quality. He asked producer Charles Mintz for a raise, but Mintz refused, reminding Disney that he was the sole contractual owner of the rabbit. Many articles and books have claimed that Disney was surprised by this revelation. In reality, he knew very well what was in their contract. His real shock was that, behind his back, Mintz bought away nearly his entire studio, leaving him with only nine loyal employees, namely Iwerks, Les Clark, Johnny Cannon and six inkers and painters (among them Disney's future wife, Lillian). Mintz produced new 'Oswald’ cartoons up until 1943, the majority directed by a still-unknown Walter Lantz, but the series was never quite as popular again. As a comic character, Oswald lasted longer. In 1935, National Periodicals (which later became DC Comics) launched a comic book series around Oswald, drawn by Al Stahl. In 1942, Dell Comics brought new 'Oswald' comics, created by writer John Stanley and artists like Dan Gormley, Dan Noonan, Lloyd White and Jack Bradbury. Also starring in this comic stories were Floyd and Lloyd, Oswald's adopted children. Production of comic stories kept going until long after Oswald had vanished from screens. In 2006, the Walt Disney Company bought back the rights to Oswald, making the rabbit part of the Disney universe.

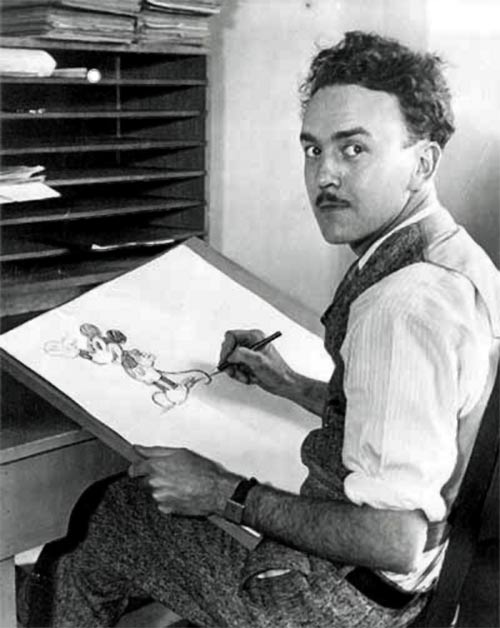

Ub Iwerks drawing for 'Plane Crazy' (1929).

Mickey Mouse

After losing the rights to Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, Disney was bankrupt once again, with only a handful of animators left. His Hollywood career seemed over. Yet he ultimately had the last laugh when Iwerks redesigned Oswald into a mouse. The new character was directly inspired by Clifton Meek's pantomime comic 'Adventures of Johnny Mouse' (1913-1915), because Disney liked Johnny's "cute ears". Originally, Disney wanted to call the character "Mortimer", but at the suggestion of his wife he eventually chose "Mickey". Chronologically, the shorts 'Plane Crazy' (15 May 1928) and 'The Gallopin' Gaucho' (August 1928) were the first to be produced, marking the debut of Mickey and Minnie Mouse. To serve as Mickey's antagonist, Pete from the 'Alice Comedies' was reintroduced in 'The Gallopin' Gaucho'. However, distributors were not impressed with these two cartoons, so they didn't find an immediate release.

Around this time, the first live-action sound films broke through, with Alan Crosland's 'The Jazz Singer' (1927) becoming a huge success. Disney had seen the Paul Terry cartoon 'Dinner Time' (1928), which experimented with a pre-recorded soundtrack, and realized this novelty could be used in animation too. Improving on Terrytoons' attempts, Disney and his team created a perfectly synchronized cartoon with sound effects, music and voices, 'Steamboat Willie' (1928). This cartoon was instantly picked up by distributors, becoming the official cartoon debut of Mickey Mouse, Minnie Mouse and the new version of Pete. 'Steamboat Willie' became a massive hit. Audiences knew that live-action films could record sounds on set, but a cartoon in which the drawings made noises was something magical. Mickey Mouse became a star and Disney was able to establish and expand a stable and financially successful studio. In 1930, he founded the Walt Disney Studios, also referred to as Walt Disney Productions. This independent studio soon evolved into one of the wealthiest multinationals of all time, nowadays known as The Walt Disney Company.

Ub Iwerks in 1929.

Style and craftmanship

Ub Iwerks played a major role in the early success of the Walt Disney Studios. An extraordinarily talented cartoonist, his characters have a vitality that could compete with the best cartoons from the 1920s. Thanks to his amazing working speed, he almost single handedly drew every frame of the 'Oswald' and early 'Mickey' cartoons. During the making of 'Plane Crazy', he allegedly made 700 drawings in one day, breaking 'Felix the Cat' animator Bill Nolan's previous record of 600 drawings in 24 hours. At his own insistence, Iwerks often worked alone. When the first Silly Symphony cartoon 'The Skeleton Dance' (1929) was made, Disney urged Iwerks to let others help him animate the picture, but he stubbornly refused.

Since Walt Disney's name is more famous with general audiences, he often receives credit for the achievements of his employees. For decades, Iwerks was no exception to this rule. Many articles, books and documentaries claimed for years that Disney was the sole creator of Mickey Mouse. In some variations, Disney watched over Iwerks' shoulder while he instructed him "how to draw" the mouse. Disney can indeed be credited with establishing Mickey's personality. In spirit, the happy mouse owed a lot to Charlie Chaplin's Tramp character and Pat Sullivan and Otto Messmer's 'Felix the Cat' cartoons. Disney also came up with the engaging storylines that made the early 'Mickey Mouse' cartoons such a huge success. Even if he didn't directly think up the plots, he streamlined the ideas and kept creative control. And from 'The Karnival Kid' (1929) up until 'Fantasia' (1940), Disney was also Mickey's original voice. But today it's firmly acknowledged, even by the Walt Disney Company itself, that Mickey's design was Ub Iwerks' creation. He gave Mickey his iconic buttoned shirt and, starting with 'The Opry House' (1929), white gloves. Since Mickey's skin is black, his hands were difficult to see when he held them in front of his body. White gloves made it easier to see what he was doing. Originally, Mickey had five fingers, but to save money he was redesigned with four.

Pete

Iwerks created many secondary characters that remain part of the Mickey Mouse universe to this day. One of them was the first Disney villain, Pete. He originated from the 1925 Alice comedy 'Alice Solves the Puzzle', in which he was still nameless, and later also appeared in 'Oswald' films. In 'Steamboat Willie' (1928), he was firmly established as Mickey's nemesis. Pete was a natural for this role, since he is a big black cat. In the 'Alice' and 'Oswald' cartoons, Pete was shown with a peg-leg, but in the early Mickey films, he had two legs. It wasn't until the newspaper comic story 'Mickey Mouse in Death Valley'' (21 April 1930) that his peg-leg returned, and that he was given the nickname "Peg-Leg Pete'. Pete's wooden leg remained a physical characteristic in the comics and was also used for his animated counterpart. However, artists had trouble remembering that it had to be his right leg that was wooden. In many cartoons and comics from the 1930s, it is sometimes his right, then his left. From 'Moving Day' (1936) on, he was drawn with two legs again. In the comics, Pete received two legs starting in 1941. Mickey and Pete are also the first cat-and-mouse duo in animation, paving the way for Hanna-Barbera's 'Tom & Jerry' (1940-1958), 'Pixie, Dixie and Mr. Jinks' (1958-1961), 'Punkin' Puss & Mushmouse' (1964-1965) and 'Motormouse and Autocat' (1969-1971), as well as Famous Studios' 'Herman and Katnip' (1940-1958), Terrytoons' 'Roquefort Mouse and Percy Cat' (1950-1955) and Matt Groening's 'Itchy and Scratchy' (1987).

Minnie Mouse, Clarabelle Cow and Horace Horsecollar

In 'Steamboat Willie' (1928), Iwerks also introduced Mickey's girlfriend, Minnie Mouse. She goes down in history as the first major female animated character, even though she was always a side character to Mickey. In many ways, Minnie was basically a clone of her male counterpart, only with huge eyelashes, a dress and more gentle gestures. In this regard, she was a forerunner of other female companions like Petunia Pig from Looney Tunes, and Winnie Woodpecker. In addition, Iwerks created Clarabelle Cow, first seen in 'Plane Crazy' (1928, official release as a sound cartoon: 17 March 1929), and Horace Horsecollar, who was introduced in 'The Plowboy' (28 June 1929). Initially presented as an actual cow and horse, the two characters were later turned into anthropomorphic funny animals, forming a couple. They were featured prominently in the early 1930s cartoons. In the 'Mickey Mouse' comics, they have remained regular cast members. Originally, Clarabelle was drawn with udders, but after the mid-1930s, at the demand of censors, this part of her anatomy was no longer shown.

From the seventh episode of the Mickey Mouse newspaper strip (20 January 1930). © Disney.

Mickey Mouse comics

Apart from animated films, the seemingly tireless Iwerks also drew the first 'Mickey Mouse' newspaper comic story, 'Lost on a Desert Island', distributed to newspapers by King Features Syndicate from 13 January 1930 on. The story was written by Walt Disney himself, borrowing heavily from the recent shorts 'Plane Crazy' (1928) and 'Jungle Rhythm' (1929), but also contained elements from older 'Oswald' and 'Laugh-O-Gram' films. However, by 8-10 February 1930, Iwerks retired from the comic and handed the strip over to his inker Win Smith. By 17 May, Smith also called it quits, after which Floyd Gottfredson continued the comic series. During a brief interruption of two weeks - from 9 to 21 June 1930 - Jack King took over, but otherwise Gottfredson remained the lead artist of the 'Mickey Mouse' newspaper comic for almost 45 years. Gottfredson developed the mouse into a proper comic hero, bringing the character to greater heights.

Leaving Disney

When Iwerks quit drawing the 'Mickey Mouse' comic strip in February 1930, he departed from the Disney Studio altogether. The ever-ambitious Walt wanted to move away from the weightless "rubber hose" animation and make his characters more realistic. In order to do so, his animators needed to professionalize their drawing skills and stay "on-model". As skillful as Iwerks was, he couldn't meet these new standards. His individualism also became problematic, since Disney wanted the company to evolve into a team effort. When Iwerks left, Disney's composer Carl Stalling followed his example. He was convinced that without Iwerks, Disney was doomed.

Episode 13 of the Mickey Mouse newspaper strip (27 January 1930). © Disney

Mickey Mouse after Iwerks' departure

History has proven both Disney and Mickey Mouse were perfectly fine without Ub Iwerks. Mickey Mouse went on to become a global cultural phenomenon. In the 1930s, movie theaters had to screen Mickey cartoons or visitors wouldn't enter them. The phrase "What? No Mickey Mouse!" became a popular euphemism for disappointment. Irving Caesar even wrote a 1932 novelty song about it: 'What! No Mickey Mouse? (What Kind Of Party Is This?)'. The laughing mouse revitalized animation at a moment when the genre seemed to lose its popularity with audiences. His success is traditionally seen as the root of the Golden Age of Animation (1930-1960). In the early 1930s, many film studios started their own animation department to compete with Disney. Many had a happy cheerful Mickey-esque character as protagonists, but none could top Disney's mouse in terms of success. He became the most merchandised fictional character of the time.

In the 'Laurel & Hardy' film 'Babes in Toyland' (1934), a monkey is seen dressed up as Mickey Mouse. In the film 'The Princess Comes Across' (1936), Carole Lombard plays a Swedish princess who names "Meeky Moose" her "favorite actor." Famous writers like John Betjeman and E.M. Forster, directors like Sergej Eisenstein, Hollywood actors Mary Pickford, Béla Lugosi and Charlie Chaplin and heads of state like U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, George V of the United Kingdom, Afghan king Mohammed Zahir Shah, Canadian Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King, South African Prime Minister Jan Smuts, Italian dictator Benito Mussolini and Japanese emperor Hirohito all declared themselves Mickey Mouse fans. After his death, Hirohito was buried with his Mickey Mouse watch. Cartoonist David Low named Disney's mouse "the most important graphic achievement in art since Leonardo Da Vinci."

Mickey Mouse : controversy

Unbelievable as it may seem today, Mickey Mouse originally met with controversy. In Germany, the cartoon 'The Barnyard Battle' (1929) was banned because Mickey fights cats who wear "pickelhaube", a pointed helmet associated with the German army. The situation worsened once Hitler took power in 1933. A 1935 Nazi newspaper stated that Mickey was a "bad role model for children", since mice are vermin. The Nazis temporarily banned Mickey Mouse cartoons, but public pressure forced them to allow screenings again. In 1935, the Romanian government also ended import of 'Mickey Mouse' cartoons out of concern that "moviegoing children would be frightened of seeing a colossal mouse on the screen." In 1937, the Yugoslavian government banned 'Mickey' comics because one plot about an uprising felt similar to the political turmoil in their country. A year later, Fascist Italy discontinued the import of U.S. media and comics, but Mussolini made an exception for Mickey Mouse. In 1941, when the United States joined World War II, both Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy banned all U.S. products, including Disney cartoons, in all their occupied countries.

Solo career (1930-1936)

Between 1930 and 1936, Iwerks ran his own animation studio at MGM. Among the people who have worked for him were Dick Bickenbach, Lee Blair, Mary Blair, Stephen Bosustow, Scott Bradley, John N. Carey, Les Clark, Ben Clopton, Shamus Culhane, Izzy Ellis, Al Eugster, Dick Hall, Ben "Bugs" Hardaway, Cal Howard, Earl Hurd, Chuck Jones, Tom Massey, Grim Natwick, Tony Pabian, Virgil Ross, Win Smith, Irven Spence and Frank Tashlin. Iwerks created his own characters, of which 'Flip the Frog' (1930-1933) and 'Willie Whopper' (1933-1934) enjoyed the most longevity. The 'Flip the Frog' cartoon 'Movie Crazy' (1931) is notable for featuring the first instance of the "characters running through doors in a hallway" gag in animation.

Win Smith once made an attempt at a newspaper comic based on 'Flip the Frog'. In the biographical entry about Win Smith, printed in the first Fantagraphics collection of 'Mickey Mouse' newspaper comics, Disney historian David Gerstein estimates that this comic strip might have been drawn in 1931. About five years after the 'Flip the Frog' comic was created, single panels from it were used to advertise 16mm releases of some of the animated shorts. These were small copies of film rolls, usually featuring one short picture, and can be described as forerunners of the home video. However, at the time, Iwerks' cartoons were never that popular. Most distributors of animated shorts and comics were more interested in 'Mickey Mouse' cartoons, given their tremendous commercial possibilities. In the United Kingdom, Dean & Son Ltd. is the only known publisher to have brought out a 'Flip the Frog' comic book, namely the 'Flip the Frog Annual' (1931), drawn by local British artist Wilfred Haughton.

In 1933, Iwerks invented a multiplane camera, which allowed an incredible illusion of depth in the animated backgrounds. It took the Disney Studios seven years before they came up with a more efficient model. Although Iwerks' multiplane camera was less flexible, it achieved the same impressive results at a cheaper cost. Unfortunately, Iwerks' technical achievements were always overshadowed by the content of his cartoons. His forgettable plots and characters lacked Disney's talent for storytelling. Even in the early 1930s, Iwerks' cartoons looked increasingly old-fashioned compared to what Disney and the Fleischer Brothers produced. By 1936, Iwerks was forced to close down his studio.

Only in later decades have his solo cartoons been revalued by animation historians and fans. Iwerks' short 'Balloonland' (1935), in which an evil pincushion man tries to prick balloon characters, is nowadays considered a cult classic.

Still from 'Balloonland', 1935.

Work for Warner Brothers, Screen Gems and Monogram

Iwerks briefly worked for Warner Bros in 1937, producing four 'Porky Pig' cartoons - the latter two directed by Bob Clampett. Between 1936 and 1940, he also joined Columbia Pictures' animation studio Screen Gems, where he contributed to their Color Rhapsody cartoons. In 1940, Iwerks also produced animation for Monogram Pictures, namely three cartoons based on Lawson Wood's 'Gran'pop'.

Return to Disney

In 1940, Iwerks returned to Walt Disney, where he was welcomed back as an old friend. However, since the studio was now working on a far more graphically sophisticated level, Iwerks didn't rejoin the animation department, but instead worked for Disney's special effects. He invented the Multihead Optical Printer, a technique that perfected interaction between an animated character and real-life actors, as featured in Disney's films 'The Three Caballeros' (1944), 'Song of the South' (1946) and 'Mary Poppins' (1964). He also worked at Disney's WED Enterprises division, co-developing many theme park attractions during the 1960s, including the Hall of Presidents in Disneyland. Iwerks' adaptation of a photocopy machine to transfer drawings directly onto animation cels saved a lot of production time. The technique was used from '101 Dalmatians' (1961) on, where the spots on the dogs could be added without having to redraw them again and again.

Apart from Disney, Iwerks also created the special effects for Alfred Hitchcock's horror classic 'The Birds' (1963).

Recognition

In 1960, Iwerks won an Academy Award for Technical Achievement for his design of an improved optical printer for special effects and matte shots. He and Petro Vlahos also shared an Academy Award of Merit (1965) for the conception and perfection of techniques for color traveling matte composite cinematography. Iwerks was posthumously given a Winsor McCay Award (1978) and named a Disney Legend in 1989.

Death, legacy and influence

Ub Iwerks passed away at the age of 70 in Burbank, California, in 1971. While his best work remains in the shadow of Disney, he is still regarded as a legend. It cannot be overstated that he graphically created Mickey Mouse, the most famous comic mouse of all time. Countless cute mice in children's books, comics and cartoons have been modeled or inspired by him. Even the fact that many cartoon characters wear gloves and only have four fingers on each hand is derived from Mickey. Mickey's round face and ears are one of the most recognizable icons on the planet, and his face is featured on numerous products. Disney comic magazines worldwide carry his name, and he is the official mascot of each Disney theme park.

In 1932, Mickey Mouse became the first fictional character to receive an Academy Award. Yet Walt Disney received the prestigious statue, not Iwerks. The same year the League of Nations named Mickey a "universal goodwill ambassador". In 1978, U.S. President Jimmy Carter named the character "a symbol of goodwill, surpassing all languages and cultures. When one sees Mickey Mouse, they see happiness." That same year, Mickey was honored as the first fictional character with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Forty years later, in 2018, Minnie Mouse also received a star on the same walk. Mickey, Minnie, Pete, Horace Horsecollar and Clarabelle Cow were among many classic animated characters to receive a cameo in Richard Williams and Robert Zemeckis' 'Who Framed Roger Rabbit?' (1988). Both Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein created pop art paintings featuring Mickey. In 2008, president Barack Obama met a Mickey Mouse actor in public and joked: "It's always great to meet a world leader who has bigger ears than me."

Plagiarism of Mickey Mouse

As can be expected, Mickey is one of the most plagiarized, parodied and ridiculed fictional characters of all time. In the 1930s, animated cartoon stars like Milton and Rita (Van Beuren), Foxy the Squirrel and Bosko (Warner Brothers) were basically rip-offs of Mickey's design. Disney even sued the Van Beuren Studios in 1931. Around the same time, cartoonists in Europe were commissioned by their publishers to draw unofficial comics starring Mickey, such as Ivan Sensin ('Dozivljaji Mike Misa', 1932), Sergije Mironovic's 'Mike i majmuna Doke' ('The Life of Mickey the Mouse and Monkey Djoka', 1932), Nikola Navojev and Vlastimir Belkic ('Mika Miš', 1936) in Yugoslavia and the Italian 'Topolino' stories by Giovanni Bissietta, Buriko, Federico Galli, Guglielmo Guastaveglia, Giorgio Scudellari, Giove Toppi and Gaetano Vitelli (1930-1935). In Japan, mangaka Shaka Bontaro drew another illegal Mickey Mouse story, 'Mikkii no katsuyaku' ('Mickey's Show', 1934). In Thailand, Wittamin drew the character 'LingGee', a hybrid of Mickey Mouse, Horace Horsecollar and Popeye. His story 'LingGee Phu Khayi Yak' (1935) plagiarized panels and storylines from Floyd Gottfredson's 'Mickey Mouse' story 'Rumplewatt the Giant'. Paul Terry's animated cartoon character 'Mighty Mouse' (1942) was also very close to plagiarism, from design down to the name. The Croatian cartoonist Veljko Kockar created an anthropomorphic cactus in 1942, Kaktus Bata, whose design and stories were very reminiscent of Mickey Mouse too.

Parodies of Mickey Mouse

Also during the 1930s, Mickey and his friends were shown in pornographic parodies, exemplified in the “Tijuana Bibles” digest-sized comic books. The Japanese animated cartoon 'Omochabako' (1936) by Komatusuzawa Hajime features the folk hero Momotaro battling a giant Mickey-esque mouse flying on a bat. Raymond Jeannin's 'Nimbus Libéré' (1944) was made in Vichy France during World War II and stars, apart from André Daix' 'Professeur Nimbus', Mickey, Donald and even Popeye bombing France. The most peculiar non-official appearance of Mickey was 'Mickey à Gurs' (1940), a text comic created by Horst Rosenthal, made while he was a prisoner in a Nazi POW camp. He didn't survive the war. Harvey Kurtzman and Will Elder's 'Mickey Rodent' (Mad Magazine, issue #19, 1955) was a hilariously cruel spoof, while Ed "Big Daddy" Roth's 'Rat Fink', Robert Armstrong's 'Mickey Rat' and Eric Knisley's 'Mickey Death' were created as vulgar parodies of the iconic mouse. In Whitney Lee Savage's silent animated cartoon 'Mickey Mouse in Vietnam' (1969), Mickey - as a symbol of the USA - is drafted to serve in the Vietnam War, where he is shot upon arrival. 1971 was a particularly rich year for Mickey parodies. In a memorable scene in Gerald Scarfe's animated short 'A Long Drawn Out Trip' (1971), Mickey lights a joint. In Neon Park's poster 'Chemical Wedding' (1971), the famous mouse is featured in a surreal comic story. The underground comic book 'Air Pirates Funnies' (1971) by Dan O'Neill, Bobby London, Shary Flenniken, Gary Hallgren and Ted Richards depicted Mickey and other Disney characters as sex and drug addicts. It was their determined and ultimately successful intention to be sued by Disney. Even today, Mickey is frequently used in subversive satire of children's media, spoofing the United States or the Walt Disney Company.

Ub Iwerks left his cultural mark on the world. His cartoons have drawn respect and admiration from people like Osamu Tezuka, Jean-Louis Lejeune and John Kricfalusi. Friz Freleng once said: "At the time, just making a character move was an accomplishment. Iwerks could make characters walk and move; he could move a house in perspective. I thought he was a genius when it came to the mechanics of animation." His name lives on in the Ub Iwerks Award for Technical Achievement at the Annie Awards. And Walt Disney himself always said that the successes of his company "all started with a mouse."