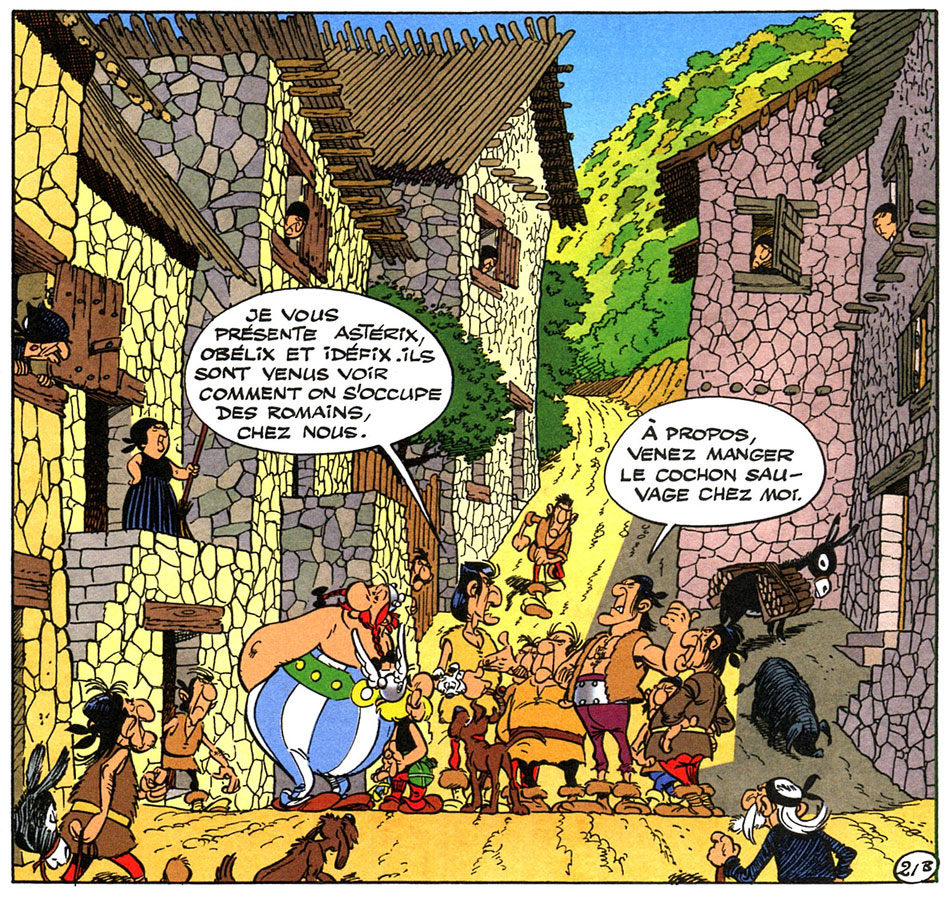

'Obelix & Cie' ('Obelix and Company').

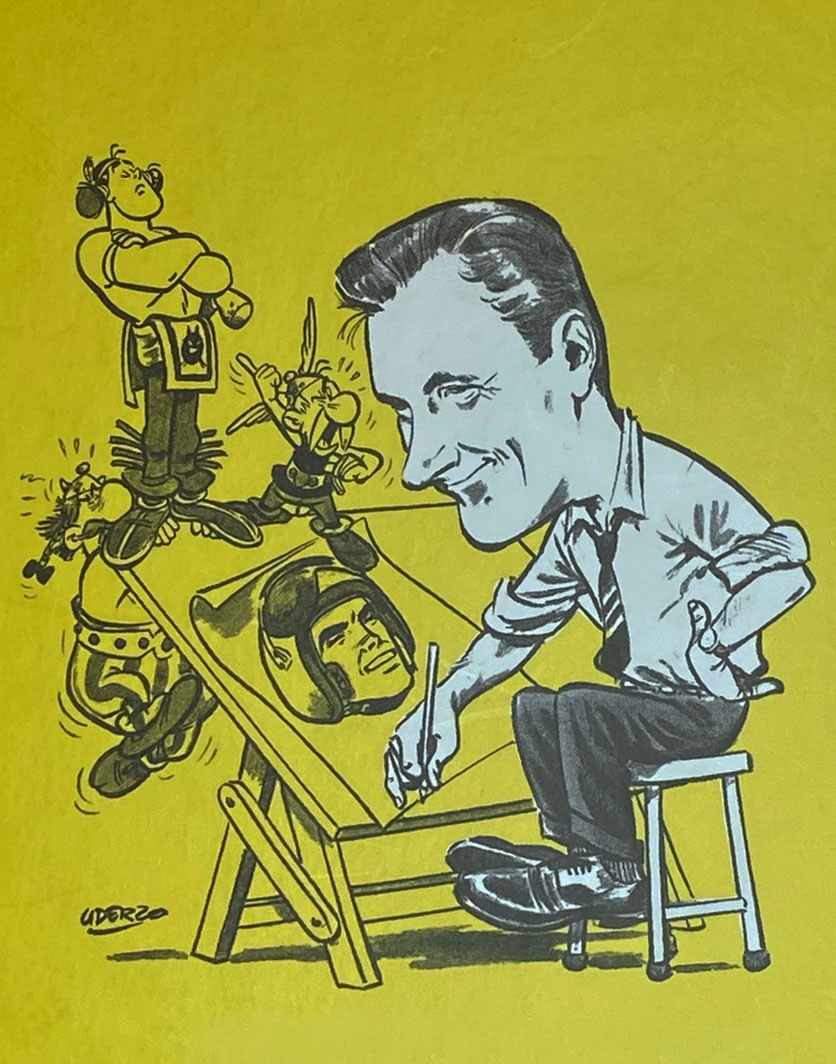

Albert Uderzo was world famous as the co-creator of 'Astérix the Gaul' (1959- ), developed in collaboration with scriptwriter René Goscinny. This humorous adventure series, set in ancient Gaul, has become one of the most surprising global success stories in comic history. The tiny invincible Gaulish warrior and his brawny menhir-carrying friend Obélix are one of the best-known European comic characters on the planet, alongside Hergé's 'Tintin' and Morris and Goscinny's 'Lucky Luke'. A remarkable achievement, given the sometimes near untranslatable puns and francophone references of scriptwriter Goscinny. 'Astérix' appeals to adults as much as children, thanks to its funny comedy, verbal wordplay and many allusions to both Gaulish-Roman culture and other historical-cultural events. The series is one of the few comics admired by intellectuals and can be credited with familiarizing many aspects of ancient Gaul and Rome among general audiences. Uderzo's talent for funny characterizations, expressive action and atmospheric scenery gave 'Astérix' its visual identity. After Goscinny's death in 1977, Uderzo continued 'Astérix' on his own, until his retirement in 2005. While 'Astérix' is considered his magnum opus, Uderzo and Goscinny created other long-running series better known in Continental Europe than elsewhere in the world, such as the humorous pirate series 'Jehan Pistolet' (1952-1956) and the brawny Native American 'Oumpah-Pah' (1958-1962). As one of the founding fathers of the comic magazine Pilote, the original homebase of 'Astérix', Uderzo was also the first artist of the realistic aviation comic 'Tanguy & Laverdure' (1959-1965), scripted by Jean-Michel Charlier.

Early life

Alberto Aleandro Uderzo was born in 1927 in Fismes, France, as the son of Italian woodworker Silvio Uderzo (1888-1985) and his wife Iria Crestini (1897-1997). The couple had met in Italy in 1915, and relocated with their first two children from Italy to France in the early 1920s. In France, they had another son called Albert, who died of pneumonia at the age of 8 months. When in 1927 their next son was born, they decided to name him Albert again. However, the birth certificate said "Alberto", because the registrar had difficulties understanding Silvio Uderzo's heavy Italian accent. After Albert(o) came two more children, including the future comic artist Marcel Uderzo (1933-2021).

By 1929, the Uderzo family had relocated to Clichy-sous-Bois in the eastern suburbs of Paris. Even though he was naturalized as a Frenchman in 1934, he still experienced xenophobia against Italian immigrants during his childhood, because of the heavy anti-Mussolini sentiments of the largely left-wing Clichy-sous-Bois population. On top of that, Albert Uderzo was born color-blind and with six fingers on each hand. While the unnecessary fingers were operatically removed, Uderzo's inability to distinguish red from green remained a lifelong problem. Still, he usually had his drawings colorized by his brother Marcel to avoid mistakes. While Uderzo initially wanted to become a clown, he quickly developed an irrepressible desire to draw. Among his graphic influences were Walt Disney, Floyd Gottfredson, Carl Barks, Walt Kelly, Alex Raymond, E.C. Segar, Alain Saint-Ogan, Calvo, Milton Caniff and Al Capp. Later in life he also expressed admiration for Cabu, André Franquin and Zep. As an artist, he was fully self-taught.

Instead of following his artistic vocation, Uderzo first tried to become an aircraft engineer, like his older brother Bruno. Despite passing his acceptance exam, the Second World War broke out and prevented him from continuing his studies. At the early age of 14, he found employment with the Société Parisienne d'Édition, a French publisher of youth and comic magazines. There, young Albert learned technical skills like lettering and image retouching. His first illustration work was a parody of Aesop's fables, 'Le Corbeau et le Renard' ('The Raven and the Fox', 1941), published in Boum, the youth supplement of the magazine Junior. Around the same time, he also met the classic comic creators Alain Saint-Ogan and Edmond François Calvo, who encouraged him to continue his graphic career. Unfortunately this had to wait until the end of the war. Between 1942 and 1945, Albert and his brother Bruno went into hiding from the Nazis and spent their days at a farm in Les Villages, Brittany. Regardless of all the war-time deprivation and misery, Albert Uderzo always remembered his years at this Breton farm as idyllic, making it a direct inspiration for Astérix' village in the same region.

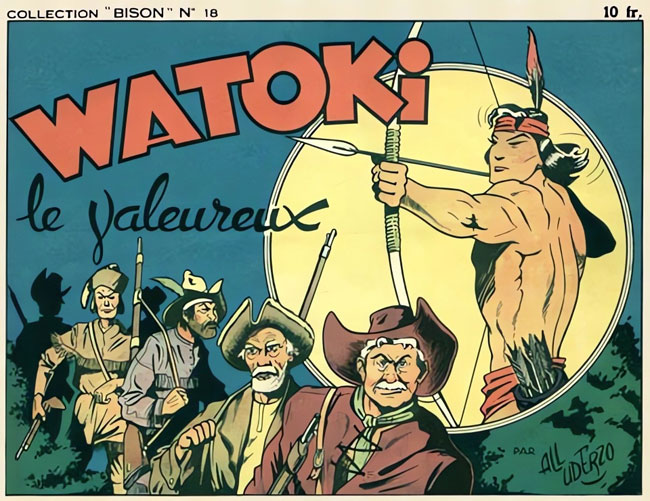

'Watoki Le Valeureux'.

From animation to comics

After World War II, Albert Uderzo tried to become an animator, inspired by Walt Disney and Pat Sullivan. In a small Parisian studio run by Renan de Vela and André Chavaud, he worked on a 11-minute black-and-white animated short, 'Carbur et Clic-Clac'. After slaving away for many days, he was so appalled with the end result, that he said farewell to animation and turned to comics. His animation director, De Vela, also went for a career change and became a publisher. He hired Uderzo to illustrate a humorous swashbuckler story written by Em-Ré-Vil (pseudonym for Marcel Reville), titled 'Flamberge, Gentilhomme Gascon'. Between October 1945 and May 1946, the story was serialized in the magazine Clic-Clac Images of Les Éditions André Renan. In later years, Uderzo dismissed his first full-length comic story as "unpromising".

After participating in a drawing contest, Uderzo was offered a publishing contract with the Éditions du Chêne in Paris. For this company, he drew the landscape-format comic booklet 'Les Aventures de Clopinard' (1946), with 16 pages of slapstick humor. He became associated with Marcel Debain's Paris Graphic agency, which provided the French press with locally produced material. Between 1946 and 1947, Uderzo drew short humor comics for the children's page of the Toulouse newspaper La Démocratie, like 'Les Aventures de Jacky' (5 episodes), 'Clodo et son Oie' (17 episodes) and 'Zidor Chasseur' (17 episodes). The character of Zidor returned in the comic story 'Zidore, l'Homme Macaque' (1947), a 'Tarzan' parody published in a booklet by Éditions S.A.E.T.L. Two years later, for the Collection Bison published by Lucien Dejoie, Uderzo made the landscape-format comic book 'Watoki le Valeureux' (1949), starring a Native American character that can be regarded as a predecessor to his later character Oumpah-Pah.

Early panel of Belloy, featuring a caricature of the artist.

O.K. magazine

During the second half of the 1940s, Uderzo was a prominent artist in the pages of O.K. magazine by the Société d'Éditions Enfantines. There, he first showcased his interest in creating fantastic adventures with muscular heroes in historical settings, a theme he further explored in his later collaborations with René Goscinny. His first creation for O.K. was the medieval strongman 'Arys Buck' and his magical sword, serialized between 12 December 1946 and 10 April 1947. Uderzo's second serial starred Arys Buck's son, Prince Rollin. Starting dramatically, the first panels of 'La Magnifique Aventure du fils d'Arys Buck, le Prince Rollin' show Arys Buck on his deathbed, handing his sword to his son. Serialized between 26 June and 2 October 1947, the story shows Prince Rollin drinking magic potion and ending up in the 20th century. Interestingly enough, while inspired by superheroes themselves, Arys Buck and Prince Rollin are both accompanied by small mustached sidekicks: Arys by Cascagnace (with winged helmet) and Rollin by Teutatès. In a way, these unlikely team-ups formed the blueprint for the future duo of Astérix and Obélix (although Goscinny would make Astérix small and his sidekick Obélix big).

Starting on 29 January 1948, Uderzo's third serial for O.K. was 'Belloy l'Invulnérable' (1948-1949), set in a folkloric version of the Middle Ages. Of all of Uderzo's early creations, this Herculean hero, with extraordinary strength and semi-invulnerability, proved to have the most staying power. While the first story was cancelled after 47 pages because of the artist's military service and the subsequent disappearance of O.K. magazine, the character reappeared in newspapers and magazines throughout the 1950s, by then scripted by Jean-Michel Charlier.

Advertising strip for Palmolive.

Newspaper cartoonist

After fulfilling his military service in Tyrol, Austria, Uderzo returned to civilian life and became a reporter-illustrator for the newspaper France Dimanche (1949-1951). During two years, he headed out to make drawings of news events "on the spot", whenever there was no photographer available. In the meantime, at the newspaper France-Soir, he was one of the artists for the vertical comic strip feature 'Le Crime Ne Paie Pas' (1950-1951), written by journalist Paul Gordeaux. This series presented readers with real-life historical anecdotes of situations, proving that "crime didn't pay". Uderzo also worked on the spin-off series 'Les Amour Célèbres' (1950), which dealt with real-life historical romances, and illustrated a comic strip adaptation of Mildred Davis' "gothic" novel 'La Chambre du Haut' (43 episodes in 1951). Further newspaper work include advertising strips for Colgate and Palmolive (1950-1951), Christmas stories for the newspaper Sud-Ouest (1955) and illustrations for the movie section 'Le Film du Jour' in L'Aurore (1956).

'Captain Marvel Jr.' (Dutch-language version, Bravo!, 1950).

Superheroes

During the 1950s, Uderzo still worked for the Paris Graphic agency, which inspired his brief venture into superhero comics. In issue #33 of the pocket comic book '34 Aventures' by Éditions Vaillant, he drew the semi-realistic 18-page story 'Superatomic Z' (1950). Then, with Paris Graphic's Marcel Debain as scriptwriter, he created 'Capitaine Marvel, Jr' (1950) by commission of the Belgian press group Le Soir for their comic magazine Bravo!. The character was based on the American superhero 'Captain Marvel' by C.C. Beck and Bill Parker, although Uderzo had never read this original. The assignment just gave him an excuse to draw stories about super strong men, much like he had done earlier with his characters Arys Buck and Belloy. His love for characters with superhuman strength revealed the influence of E.C. Segar's 'Popeye' and Al Capp's 'Li'l' Abner'. In fact, Uderzo signed many of his early comics as "Al Uderzo", as a tribute to Capp.

Belloy - 'La Princesse Captive' (1956).

Brussels period

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, Belgium was the capital of the continental European comic scene, thanks to the success of magazines like Tintin and Spirou. Invited by the International Press agency of Yvan Chéron, Uderzo decided to stay in Brussels for a while, in search of better job opportunities. The International Press firm shared an office with the World's P. Presse agency, headed by Chéron's brother-in-law Georges Troisfontaines. There, Uderzo got in touch with Belgian comic legends like Victor Hubinon, Eddy Paape, MiTacq and Jean-Michel Charlier, who all worked for Spirou and the other magazines of Éditions Dupuis. Especially with Charlier, he struck a friendship and fruitful collaboration, starting with the relaunch of the 'Belloy' comic in the Belgian newspaper La Wallonie. In this new incarnation, Belloy's educator Père Hoc sometimes uses an alcoholic beverage that increases one's strength and courage, a plot element that later returned as the magic potion in Uderzo and Goscinny's 'Astérix' stories. After two stories in La Wallonie ('Le Chevalier sans Armure' and 'La Princesse Captive'), the 'Belloy' comic was abandoned again. Later that decade, between 1955 and 1958, the 'Belloy' stories were reprinted in Pistolin, followed by two new episodes ('Le Baron Maudit', 'L'Homme Qui Avait Peur de Son Ombre'). During the 1960s, the 'Belloy' stories were once again reprinted in Pilote and La Libre Junior.

Uderzo & Goscinny

By 1951, Uderzo was working at the brand new Parisian division of International Press/World's P. Presse, where he was joined in the art department by the artist Martial Durand. Another newcomer there was René Goscinny, an aspiring cartoonist who had just returned from the United States. Expecting a fellow Italian because of the name, Uderzo was surprised to learn that Goscinny in fact had French origins. And even though their personalities differed - Goscinny was extroverted, playful and intellectual, Uderzo more anticipating, pragmatic and traditional - they proved a perfect mix for some of the best creations in Franco-Belgian comic history. Their collaboration took off in November 1951, when Uderzo began illustrating 'Qui à Raison?' and 'Sa Majesté Mon Mari', two columns about everyday life and proper manners, written by Goscinny under a pseudonym in the Dupuis women's magazine Bonnes Soirées. Uderzo provided the illustrations until 1953, after which he was succeeded by Charlie Delhauteur.

'Jehan Pistolet'. Dutch-language version.

Jehan Pistolet and other comics in La Libre Junior

Through International Press, Uderzo and René Goscinny were productive contributors to La Libre Junior, the junior supplement of the Belgian newspaper La Libre Belgique. Of all of their creations in La Libre Junior, the humorous series about wannabe pirate 'Jehan Pistolet' (1952-1956) had the most longevity, and was the first showcase of Goscinny and Uderzo's talent for creating pun and gag-filled adventures against a historical backdrop. Debuting on 26 June 1952, the story is set in the 18th century and revolves around a young waiter called Jehan, who works in a tavern in Nantes. Dissatisfied with his job, he decides to become a privateer and buys a ship, "La Brave". He assembles a crew consisting of various colorful characters, including his second captain Hugues, cooks Bertrand and Pierrot, cannoneer and navigator Gilles, tiny sailor P'tit René (a caricature of René Goscinny) and Jasmin the parrot. Jehan and his crew work for the French king and sail the seven seas looking for treasures and new colonies, or to fight off villainous pirates.

Several elements of 'Jehan Pistolet' already hint at Goscinny and Uderzo's later work. 'Jehan Pistolet' satirized a specific genre, in this case nautical and pirate stories, and much like 'Astérix', the protagonists celebrate every happy ending with a banquet. 'Jehan Pistolet' allowed Uderzo to show off his rich illustration work and talent for visualizing Goscinny's funny scripts.

'Luc Junior' in La Libre Junior, 1956.

Uderzo and Goscinny also created La Libre Junior's mascot: 'Luc Junior' (1954-1957). Luc was a young reporter in the tradition of 'Tintin', who starred in exciting and humorous adventure stories. With his friend Laplaque and his faithful companion, the dog Alphonse, he investigated seven cases before his authors handed him over to Sirius and then Greg. In 1956, International Presse released one album of the comic: 'Junior en Amérique' (1956). A complete volume with all seven stories created by Uderzo and Goscinny was released in 2014. Between November 1954 and June 1955, La Libre Junior also ran Goscinny and Uderzo's only realistic comic serial, starring shark hunter 'Bill Blanchart'.

Additional International Press/World's P. Presse work

Besides his successful collaborations with Jean-Michel Charlier and René Goscinny, Albert Uderzo was assigned on a great many other projects by the International Press/World's P. Presse agencies, often for the Belgian market. With scriptwriter Octave Joly, he collaborated on a comic strip biography of Marco Polo (1953), another comic for La Libre Junior. Between 1953 and 1958, Uderzo additionally illustrated educational stories and vertical strips for the parent newspaper La Libre Belgique. For Bonnes Soirées magazine, Uderzo provided illustrations for a section about history, 'L'Histoire Vivante', most notably installments about the French resistance veteran Valérie André (1954) and the French queen Marie-Antoinette (1955). In Spirou magazine, he illustrated the similar comic story 'Le Fils du Tonnelier' (1954, script by Jean-Michel Charlier) in the educational series 'Les Belles Histoires de l'Oncle Paul'.

Again with Octave Joly as his scriptwriter, Uderzo appeared in the pages of Risque-Tout, a short-lived tabloid comic magazine initiated by World's P. Presse as a companion title to Spirou. Between 1955 and 1956, they created two serials of 'Tom et Nelly' (1955-1956), an adventure comic about two kids who escape from a terrible orphanage in London. After the cancellation of Risque-Tout, the series moved over to Spirou in 1957, although by then José Bielsa had taken over the art duties.

'Tom et Nelly' (Risque-Tout #13, 1956).

Édifrance/Édipresse

In 1956, Goscinny and Uderzo's association with both the Belgian agencies came to a sudden end. In that year, René Goscinny and Jean-Michel Charlier had tried to establish a union for comics creators. As scriptwriters, both were treated as second-class collaborators, and left out of any negotiations between World's P. Presse and its artists. When World's P. Presse's agency owner Georges Troisfontaines caught wind of this mutiny, he made Goscinny the scapegoat and instantly fired him. Out of solidarity, Uderzo and Charlier stuck with Goscinny and also left. During the second half of the 1950s, the team of Goscinny, Uderzo and Charlier expanded their activities for other publishers and clients. As independent creators, they were now assured that they would have ownership over their creations.

Together with World's P. Presse's former publicity manager Jean Hébrard, the three men founded a syndicate consisting of two different agencies, ÉdiFrance and ÉdiPresse. With Uderzo as lead illustrator, Goscinny and Charlier were tasked as copywriters for advertisements and comic features. The syndicate launched publications like Clairon for Fabrique-Union toys, Pistolin (1955-1958) for the Pupier chocolate company and the monthly Jeannot (1957-1958), a joint venture between Nappey watches, Klaus chocolate and Gilac plastic. Several of Goscinny and Uderzo's earlier creations reappeared in the new Édipresse projects; 'Jehan Pistolet' was reprinted in Pistolin under the title 'Jehan Soupolet', and in 1957 'Bill Blanchart' returned in the Edifrance magazine Jeannot. Among the other advertising titles launched by Édifrance was Milliat Frères Magazine (1956) for Milliat Frères pasta, for which Uderzo drew the front page comic features 'Le Neveu de d'Artagnan' (script by Charlier) and 'L'Étonnante Aventure du Seigneur Raviolitos' (script by Goscinny).

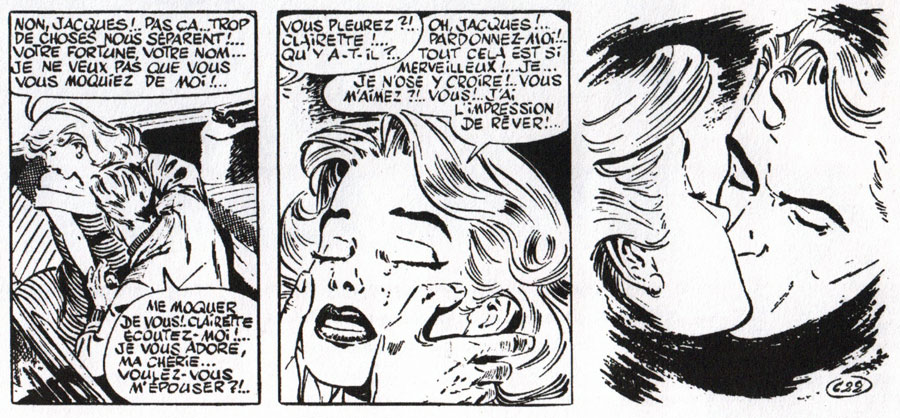

An extremely rare dummy issue of an Édifrance newspaper supplement called Le Supplement Illustré (1956) had two new co-creations by Uderzo. First the humor 'Antoine l'Invincible' with René Goscinny, and also 'Clairette' (1957), a realistic romance serial written by Jean-Michel Charlier in the tradition of Stan Drake's 'Heart of Juliet Jones'. As the supplement never got off the ground, most comics from Le Supplement Illustré were never heard of again. However, in 1957, Édifrance syndicated 'Clairette' to the Parisian "naughty" magazine Paris-Flirt. Also with Charlier, Uderzo reprised 'Belloy' in Pistolin, and produced the comic book 'Les Aventures de Jim Flokers: La Diligence de Santa-Fe', commissioned by Floker's corn flakes. This realistic western story would prove to be a try-out for Charlier's later western comic 'Blueberry', created with Jean Giraud. In addition, Uderzo drew three stories for Pistolin's 'Grands Noms de l'Histoire de France', a historical feature by Jean-Michel Charlier similar to Spirou's 'Oncle Paul' comic.

However, the most fruitful team-up proved to be that of Goscinny and Uderzo. They shared a similar sense of humour and complemented each others' talents perfectly. Their production rate rose to the point that Uderzo sometimes drew nine pages a week, even inking everything instantly, rather than sketching it out first. In Pistolin, Uderzo also illustrated Goscinny's column 'Les Enfants Héroïques' (1955-1958), which recounted the heroic acts of courageous children. Later installments were illustrated by Jean-René Le Moing. Between 1957 and 1959, Goscinny and Uderzo took over the comic feature 'Benjamin et Benjamine', starring the mascot of Benjamin magazine. The comic was previously created by Christian Godard, and then continued by Jen Trubert and Roger Lécureux. A rare entry in Goscinny and Uderzo's catalog was 'Monsieur et Madame Plume' (1958), a gag strip syndicated by Édifrance to Paris Flirt (an earlier strip had appeared under the title 'Routine' in Radio-Télé).

Tintin magazine

By 1957, René Goscinny had become a prolific scriptwriter for Tintin magazine, writing a great many comics for several of the magazine's artists. He also brought along Uderzo. Their first creation for the magazine was 'Poussin et Poussif' (1957-1958), starring an energetic toddler and an unfortunate Great Dane dog, who is tasked with keeping the boy safe. However, the little boy always manages to crawl away, urging the panicky pet to try and get the child safely back home, often hurting and endangering himself in the process. Although only three episodes were published, readers loved the comic, which opened doors for other new Goscinny-Uderzo creations in Tintin.

'Oumpah-Pah'. Dutch-language version.

Oumpah-Pah

Encouraged, Uderzo and Goscinny took the opportunity to dust off an old concept they had developed, but which had been rejected by both American and French publishers. In fact, the giant Native American 'Oumpah-Pah' was the first joint creation they had done back in 1951. When it was finally greenlighted, it debuted in Tintin on 2 April 1958. 'Oumpah-Pah, Le Peau-Rouge' (1958-1962) is set in Canada (New France) during the 18th century, when French colonialists explored the country. The main character Oumpah-pah is a hefty, brave and strong Native American who befriends a scrawny dignified French military officer, Hubert de la Pâte Feuilletée.

Goscinny studied documentation thoroughly to know more about the time period, but didn't hold himself back when it came to poking fun at every conceivable cliché about Native Americans. Just like in the 'Lucky Luke' stories he wrote for Morris, their animalistic names and communication through smoke signals were running gags. European settlers are mocked with the same wit and nobody can deny that Oumpah-Pah is effectively the hero. Graphically, Uderzo made Oumpah-Pah another muscular strongman, with physical resemblances to earlier creations like 'Watoki' and 'Belloy'. With this comic, Uderzo also dropped the Al Capp-inspired semi-realism, and fully switched to a round and dynamic drawing style, more suitable for slapstick action, that would further come to blossom in 'Astérix et Obélix'. Other elements were also later recycled in the 'Astérix' comics. Much like how the Gauls in 'Astérix' frighten the Romans, the Native Americans scare off colonials with their physical strength and hide in bushes and trees. In the third Oumpah-Pah' story, the main characters even encounter some incompetent pirates.

The 'Oumpah-Pah' book collections have been translated into many languages, including Dutch ('Hoempa Pa'), German ('Umpah-Pah'), Danish ('Umpa-Pa'), Norwegian ('Ompa-Pa'), Swedish ('Oumpa-Pa'), Finnish ('Umpah-Pah'), Spanish ('Oumpah-Pah'), Portuguese ('Humpá-Pá'), Italian ('Oumpah-Pah'), Polish ('Umpa-Pa Czerwonoskóry') and Russian ('Умпах-Пах').

La Famille Moutonet

In 1959, Uderzo and Goscinny made another comic series for Tintin, 'La Famille Moutonet', starring a grandfather with a military background who is tormented by his overly busy grandchildren, Totoche and Mimi. It only lasted two short stories, but was nevertheless in 1961 revived as 'La Famille Cokalane' in the French edition of Tintin. Having basically the same cast and set-up, this reboot came about at the instigation of Pétrole Hahn, whose shampoo products were sponsored at the bottom of each comic strip. Since their products were not available in Belgium, 'La Famille Cokalane' appeared only in the French edition of Tintin. After a first episode drawn by Albert Uderzo, the next fifteen installments were illustrated by a different artist, who has not yet been identified.

Pilote

Uderzo and Goscinny's 'Oumpah-Pah' ran in Tintin until 1961, but wasn't the instant hit one would expect. Perhaps because Tintin generally carried more serious comics, the series ended up on the eleventh spot in the annual readers' poll. Disappointed, the authors decided to cancel their comic, also because by then they already had a heavy workload for their own magazine. In late 1958, the Édipresse/Édifrance team was approached by advertising executive François Clauteaux to create a special paper for youngsters, a mix of comics with articles about current affairs, science and history, modeled after Paris-Match magazine. Joining in on the venture were Radio-Luxembourg and two top editors of the regional Centre Républicain newspaper. After several mock-ups, the first issue of Pilote magazine appeared on 29 October 1959. In its first years, the magazine underwent several editorial, stylistic and personnel changes, with the radio connections becoming less prominent and an increasing representation of the comics content. In early 1961, the magazine was bought over by Éditions Dargaud, the publishing house that also released many of Pilote's comic series in book format, and so became an important competitor to the leading Belgian comic publishers, Dupuis (Spirou) and Le Lombard (Tintin).

Cover illustrations for Pilote #14 (28 January 1960) and #267 (3 December 1964).

From the start, René Goscinny and Jean-Michel Charlier served as Pilote's chief editors, as well as its main scriptwriters - Goscinny for the humor content, Charlier for the more serious adventure serials. From the magazine's first issue on, Albert Uderzo worked with both writers on the creation of two iconic series of Franco-Belgian comics: 'Astérix' with Goscinny, and 'Tanguy et Laverdure' with Charlier. So by 1961, Uderzo was already working on two major series, four pages a week, making it an easy decision to drop 'Oumpah-Pah' in Tintin.

Together with Jean-Michel Charlier, Uderzo also edited the short-lived newspaper Sunday supplement L'Illustré du Dimanche (1967), featuring comics originally published in Pilote. It ran for 24 issues with regional newspapers like Le Provençal, Midi Libre, Sud-Ouest and Paris-Normandie.

'Tanguy et Laverdure' (Pilote #294, 10 June 1965).

Tanguy et Laverdure

In the debut issue of Pilote magazine of 29 October 1959, the very first comic that the reader encountered was an aviation comic by Jean-Michel Charlier and Albert Uderzo: at first called 'Michel Tanguy', but later retitled 'Tanguy et Laverdure'. In the debut episode, the two main heroes are transferred from the Salon-de-Province Air School to the French flying school in Meknès, Morocco, to improve their skills. There, they are quickly sent on a dangerous mission in the snowy mountains to retrieve a lost warhead with confidential information. Later, they join the Cigognes squadron, where they pilot the Mirage III plane. Their next missions bring them to the Dijon air base, Tel Aviv and Greenland.

Narratively, the 'Tanguy et Laverdure' comic has all the ingredients of the typical Charlier comic: a straightforward and serious hero with a more reckless and goofy sidekick as comic relief, keen documentation and exciting and well-structured plots filled with companionship, betrayal and thrilling action. In many ways, the series covered the same territory as Charlier's other aviation comic, Spirou's 'Buck Danny', drawn by Victor Hubinon. But while Buck Danny and his companions served in the U.S. Army, Michel Tanguy and Ernest Laverdure were French, making them more relatable to Pilote's readership. Graphically, Uderzo proved he was as equally adept at realism as in humor, taking great care in correctly depicting the various aircrafts. While his characters were not caricatural, he allowed himself more freedom in their expressions, especially with the oddball Ernest Laverdure, whom Uderzo had largely modelled after himself. One story, 'Les Pirates du Ciel', was drawn by Uderzo in collaboration with his brother Marcel Uderzo and Jean Giraud.

Published in book format by Dargaud, the 'Tanguy et Laverdure' series was translated into Dutch, English ('The Flying Furies', also as 'The Aeronauts'), German ('Mick Tanguy'), Danish ('Luftens Ørne'), Swedish ('Jaktfalkarna'), Finnish ('Haikaralaivue'), Spanish, Portuguese, Indonesian, Serbian and Croatian. 'Tanguy et Laverdure' were adapted into a live-action TV series, 'Les Chevaliers du Ciel' (1967-1970), with the spin-off 'Les Nouveaux Chevaliers du Ciel' (1988-1991) and a film, 'Les Chevaliers du Ciel' (2005), directed by Gérard Pirès, which was only loosely based on the original comic.

'Tanguy et Laverdure'. Dutch-language version.

Tanguy & Laverdure post-Uderzo

By 1966, Uderzo had to devote all his time to his hit series 'Astérix', and he retired from the 'Tanguy et Laverdure' comic. After eight albums, he passed the pencil to Jijé, who continued the comic for nearly fifteen years, aided by his assistants Daniel Chauvin and Patrice Serres. After Jijé's death in 1980, Serres became the new artist for three more books, followed by a final installment drawn by Al Coutelis. Shortly afterwards, scriptwriter Charlier, seemingly ending the series altogether. In the early 2000s, however, Tanguy et Laverdure's plane took off again with Jean-Claude Laidin as new scriptwriter, and Yvan Fernandez, Renaud Garreta, Frédéric Toublanc, Julien Lepelletier and Sébastien Philippe either sharing or alternating on the art duties. Since 2018, Patrice Buendia and Frédéric Zumbiehl have been the franchise's new scriptwriters. In 2016, the spin-off series 'Tanguy et Laverdure Classic' was launched, with stories set in the same time period as the original Charlier-Uderzo episodes. Writers on duty have been Patrice Buendia and Hubert Cunin, with Matthieu Durand doing the artwork.

First appearance of Astérix and Obélix in 'Astérix the Gaul'.

Astérix

With Goscinny, Uderzo created a new comic series that would change the world of Franco-Belgian comics for good. However, the two friends didn't settle on the little Gaul from the start, although they wanted something historical. Contractual restrictions by publisher Le Lombard kept them from continuing their Tintin comic 'Oumpah-Pah' in Pilote. So instead, they picked out a comic version of the medieval folk tale about the trickster fox Reynard, 'Le Roman de Renart'. However, it turned out comic artist Benjamin Rabier had already beaten them to the idea and Jean Trubert was also preparing a comic book version about Reynard. Goscinny decided to delve deeper, all the way back to the starting point of all French history books: Gaulish culture. At school, everybody learned about the Gaulish chieftain Vercingetorix and his brave resistance against the Romans. Since the time period was such common knowledge among French readers, Goscinny and Uderzo could have all the fun they wanted with this setting, because everybody would get the references.

'Astérix' is set in the 1st century BC, around the time of Caesar's conquest of Gaul (ancient France). As the famous title page of every album explains: Caesar apparently hadn't conquered all of Gaul. One tiny village in the western-northern French region Brittany (Bretagne) keeps resisting the Roman oppressors. This is the place where Astérix and his fellow villagers live. The choice for this homebase was self-evident. Goscinny wanted it to be near the ocean, in case storylines would require the characters to sail to other countries. Uderzo favored Bretagne because he had lived there during World War II. And since the province was famous for its many archaeological examples of Gaulish culture - such as the famous menhirs of Carnac - it was a done deal. At the time, the creators weren't aware that there already had been two comics about ancient Gaul, namely Jean Nohain and Poléon's 'Totorix' and Fernand Cheneval's 'Aviorix'. Luckily, as it turned out, because otherwise they might have dropped that idea too.

Astérix: characters

When graphically creating the characters, Uderzo initially drew a big muscular Gaul as the main hero, much in line with his previous heroes. As a sidekick, he added a smaller guy for comic relief. However, Goscinny suggested to swap the two roles, and Astérix and Obélix were born. In the debut episode 'Astérix le Gaulois' ('Asterix the Gaul', 1959), most of the recurring cast was established. While Astérix is small and hot-tempered, he is nevertheless very smart. Together with the druid Panoramix (Getafix in the English translation), they are easily the most intelligent people in the village. Panoramix provides all the villagers with a magic potion which makes the Gauls strong enough to beat up the Romans time and time again. The only person not allowed to drink the potion is Astérix' best friend, the local stonecutter Obélix, who fell into the cauldron of the magic potion when he was just a small boy and is therefore already strong enough. A brawny man, he enjoys beating up Romans, eating and hunting for wild boars. Unfortunately he is not very bright and in constant denial over his obesity. However he is such a charming doofus that he is easily everyone's favorite character, particularly with children. Although Obélix and Astérix often quarrel, their friendship is strong and heartwarming. Goscinny and Uderzo based much of the duo's dynamic on Laurel & Hardy, which is notable down to their hatwear.

Astérix - 'La Grande Traverse' ('The Great Crossing').

Abraracourcix (Vitalstatistix) is the village's self-important chieftain who is carried around on a shield, as was common among Celtic tribes, but constantly falls off due to his carriers' clumsiness and stupidity. Assurancetourix (Cacofonix) is the local bard, but sings so awfully that everyone always tries to shut him up, particularly the blacksmith Cetautomatix (Fulliautomatix) who often keeps a hammer near. The final recurring character introduced in Astérix' debut album is Julius Caesar. He acts as the town's nemesis and is frustrated that he can't conquer the Gaulish village. Yet he is not portrayed as diabolical. When defeated or humiliated, he usually shows some grace or a sense of fair play towards the Gauls. He even helps them punish some of his subordinate centurions or far more villainous Romans.

Other recurring villains in the series are the pirates, although they are less of a threat. They made their debut in 'Astérix Gladiateur' ('Asterix the Gladiator', 1962) where they make the fatal mistake of attacking Astérix and Obélix. Originally they were just intended as a shout-out to the pirate comic 'Barbe Rouge' by Jean-Michel Charlier and Victor Hubinon, which also ran in Pilote. The three main pirates are even directly modeled after Barbe Rouge, the one-legged Triple-Patte and Baba the crows' nest look-out. But they quickly became a running gag in every 'Astérix' album. No matter where the buccaneers travel, they always happen to come across "the crazy Gauls" somewhere, much to their own misfortune. Since 'Barbe Rouge' was unknown outside Continental Europe, the reference to Charlier and Hubinon's comic was lost on most foreign readers. Today, now that 'Barbe Rouge' has more or less fallen into obscurity, they have become a prime example of a parody which outlived the original spoof material.

'Astérix, Légionnaire' ('Asterix the Legionary'), The pirates on the raft are a parody of Théodore Géricault's classic painting 'Le Radeau de la Méduse' ('The Raft of the Medusa', 1819). An extra pun is the pirate captain's remark: "Je suis médusé!" ("I'm stupified", providing wordplay on the name "Medusa").

Another major character, Obelix' dog Idéfix (Dogmatix), actually started out as a running gag but quickly became a full cast member. All throughout the story 'Le Tour de Gaule d'Astérix' ('Asterix and the Banquet', 1963), Astérix and Obélix are followed by a tiny, white mustached dog, who is noticed and adopted by Obélix in the final strips. Pilote organized a contest to find a name for the canine. Four young readers, Hervé, Dominique, Anne and Rémy, came up with "Idéfix", a pun on the French word "idée fixe" for an obsessive idea. Other regulars in the franchise are the village elder Agecanonix (Geriatrix, 1962) and his far younger wife (1970). Chieftain Abraracourcix also received a feisty partner in 1964, Bellefleur (Impedimenta). Finally, in 1969, fish monger Ordralfabetix (Unhygienix) was introduced. His merchandise is never fresh and so sparks off numerous village fights. But despite all of their internal struggles, the Gaul village is still united against their common enemy, the Romans. Every story ends with the villagers celebrating at a large, round table in the middle of the forest, while drinking beer and eating roasted wild boars. Even Assurancetourix is allowed to be there, but out of precaution against his possible warbling is bound and gagged against a tree.

Astérix: visual style

At the time, nobody believed in Astérix' commercial potential. If the authors hadn't had their own magazine with Pilote, the comic might never have been published. But 'Astérix' defied all expectations and became a runaway success. Sales of the book collections by publisher Dargaud rose with each album. Thanks to Uderzo's inviting slapstick drawings and Goscinny's witty scripts, 'Astérix' appeals to both children and adults. A large part of the success of 'Astérix' can be attributed to Goscinny's multi-layered scripts, filled with witty slapstick, linguistic comedy, amusing running gags and historical-cultural references, often with deliberate anachronisms. Since Uderzo always praised his friend in interviews, while remaining humble about his own contributions, it is often underestimated how important the artist was in the series' lasting popularity. Uderzo designed the characters' looks, their village and their universe. Without him, 'Astérix' would have lacked Obélix and Idéfix, since Goscinny originally didn't see much in these characters.

Above all, Uderzo was a marvellous illustrator, who combined the instant readability of the Belgian "Ligne Claire" ("Clear Line") with stunningly detailed artwork and Disneyesque character appeal. His humans look like believable individuals and are amusingly portrayed with dynamic movement and subtle expressions. In the 'Astérix' years, Uderzo was particularly fond of drawing bulbous-nosed characters with huge potbellies. Whenever he depicted stereotypical presentations of people, he added little subtle touches that were amusing in their recognizability. Especially the characters' voyages to Britannia, Germania, Hellas (Greece), Hispania (Spain), Helvetia (Switzerland) and Belgica gave the creators the opportunity to make stereotypical jokes about the local people and everything these countries are internationally famous for. Not only do Europeans recognize these stereotypes easily, they also feel honored whenever Astérix visits their country.

'Astérix Chez Les Goths' ('Astérix and the Goths').

Uderzo was also a master caricaturist. He frequently gave celebrities cameos in the series, several mostly known in the francophone world, like TV host Guy Lux (in 'Le Domaine des Dieux'), film actor Lino Ventura ('La Zizanie), comedian/musician Annie Cordy ('Astérix Chez les Belges'), film actors Bernard Blier and Jean Gabin ('L'Odyssée d' Astérix'). Others are internationally famous, like French politician Jacques Chirac, Laurel & Hardy ('Obelix & Co'), Sean Connery ('L'Odyssée d' Astérix), The Beatles ('Astérix Chez les Bretons') and Kirk Douglas ('La Galère d' Obélix'). Colleagues and friends of Uderzo also received cameos, such as Jean Graton ('La Serpe d'Or'), film and TV producer/screenwriter Pierre Tchernia ('Astérix en Corse') and 'Astérix' film soundtrack composer Gérard Calvi ('Astérix en Hispanie'). Another one of Uderzo's passions was drawing cute animals, from the panicky wild boars who try to hide from Obélix, to the village rooster crowing at dawn.

Chanteclairix, the Gaulish rooster (short story from 'Astérix et la Rentree Gauloise'/'Asterix and the Class Act', 2002).

Goscinny's hilarious scripts rarely looked better when executed by Uderzo's pencil. From funny facial expressions to the over-the-top fight sequences where Obélix knocks away entire legions of Romans as if they were pins in a bowling game. Nobody could depict banquets so deliciously that one can almost taste the food. Several of Goscinny's referential gags demanded a decent visual execution, such as Uderzo's parodies of famous paintings by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Theodore Géricault, Rembrandt van Rijn, or scenes from famous movies like 'Cleopatra' (1963) and Federico Fellini's 'Satyricon' (1969).

Latin edition of 'Astérix et Cléopâtre' ('Astérix and Cleopatra').

Goscinny and Uderzo read various books and visited many museums to study the Gallo-Roman time period. While Goscinny did most of the research for the stories, Uderzo depicted authentic clothing, weapons, sculptures, architecture, customs and objects with much attention to detail. Two Dutch authors, René van Royen and Sunnya van der Vegt, investigated the historical accuracy of the 'Astérix' universe in three books, published by Bert Bakker: 'Asterix en de Waarheid' ('Asterix and the Truth', 1997), 'Asterix en de Wijde Wereld' ('Asterix and the Wide World', 2002) and 'Asterix en Athene: Op Naar Olympisch Goud!' ('Asterix and Athens: Onward to Olympic Gold!', 2004). They actually came to the conclusion that various objects, customs, architecture and geographical details were depicted far more historically accurately and realistically than one would expect from a humorous comic strip. Sometimes Uderzo didn't even have proper documentation, but his knowledge of the era was so exquisite that he could easily imagine how certain things might have looked. In 'Le Tour de Gaule d'Astérix' ('The Banquet', 1963), Uderzo once drew the harbor of Gesobicratie (nowadays Le Coquet) off the top of his head, only to be amazed when a historian complimented him for its accuracy!

Uderzo and Goscinny also traveled a lot, bringing back all the necessary photographs of archaeological sites and landscapes. Some of Uderzo's drawings of ancient cities and nature scenery are so picturesque that they can compete with pictures in a tourist guide. In the backgrounds, Uderzo hid numerous visual gags in the backgrounds, sometimes so subtly that they don't distract from the main action. As a result, some of them are only discovered after several re-readings.

The famous cheese fondue scene from 'Astérix Chez les Helvètes' ('Astérix in Switzerland').

Astérix: global success

All in all, 'Astérix' was a runaway success from the start. Sales rose with each album and Pilote eventually turned the character into the magazine mascot. Despite being the most "European" comic of all time, 'Astérix' also managed to become a global success. The series has been translated into more than 115 languages and dialects, including Arabic, Bengali, Chinese, English, Hindi, Indonesian, Japanese, Persian, Russian, Thai and Turkish. All across the world, it shares the stage with Hergé's 'Tintin' as perhaps the most recognizable European comic ever, and many schools have used 'Astérix' comics to help their students read and learn French.

In 1963, the series debuted in the United Kingdom in the magazine Valiant, where it ran as 'Little Fred and Big Ed'. The setting was changed from Gaul to Celtic Britain. In 1965, the series also ran in Ranger, again with Britain as setting, under the subtitle "Britons, Never, Never, Never Shall Be Slaves", in reference to the refrain of "Rule Britannia". Here Asterix and Obelix were renamed 'Beric and Doric'. However, once 'Asterix in Britain' was published, the translators could no longer present the Gauls as Britons. So from 1969 on the series was finally simply translated as 'Asterix and Obelix', making them Gauls once and for all. Legendary translators Anthea Bell and Derek Hockridge made a successful effort to do Goscinny's writing justice and came up with many clever English-language puns and verbal jokes of their own. In Germany, 'Asterix' was originally translated as 'Siggi und Babarras', when it ran in Rolf Kauka's Fix und Foxi magazine in 1967. They too eventually settled on 'Asterix und Obelix'.

The international fame of 'Astérix' remains somewhat amazing, considering its unapologetic and sometimes untranslatable puns and references to francophone culture. In 'Le Tour de Gaule d'Astérix' ('Asterix and the Banquet', 1963), for instance, Astérix and Obélix travel through Gaul, meeting people from Paris, Lyon and Nice, all depicted according to stereotypes attached to these regions. In the same story, the Gauls meet four men in a bar in Marseille, who are caricatures of the main cast from the 1932 film 'Marius' by Marcel Pagnol.

'Les Lauriers de Cesar' ('Asterix and the Laurel Wreath', 1972),

Astérix: film adaptations

'Astérix' also gained greater international fame through films. In 1965, the Belgian animation company Belvision adapted the very first 'Astérix' story, 'Asterix the Gaul' into an animated feature, directed by Ray Goossens. However, Uderzo and Goscinny weren't consulted beforehand, and by the time they learned about the upcoming film, it was already too late to prevent its premiere. While the film did well at the box office, it was a very literal adaptation of the original comic and so Goscinny and Uderzo stipulated more creative control over Belvision's next 'Astérix' film, 'Astérix and Cleopatra' (1968). Goscinny was well aware that an animated feature required a different approach than a comic, so he removed specific scenes while writing new material taking full advantage of the creative possibilities of cinema. As a result, 'Astérix and Cleopatra' was much better received.

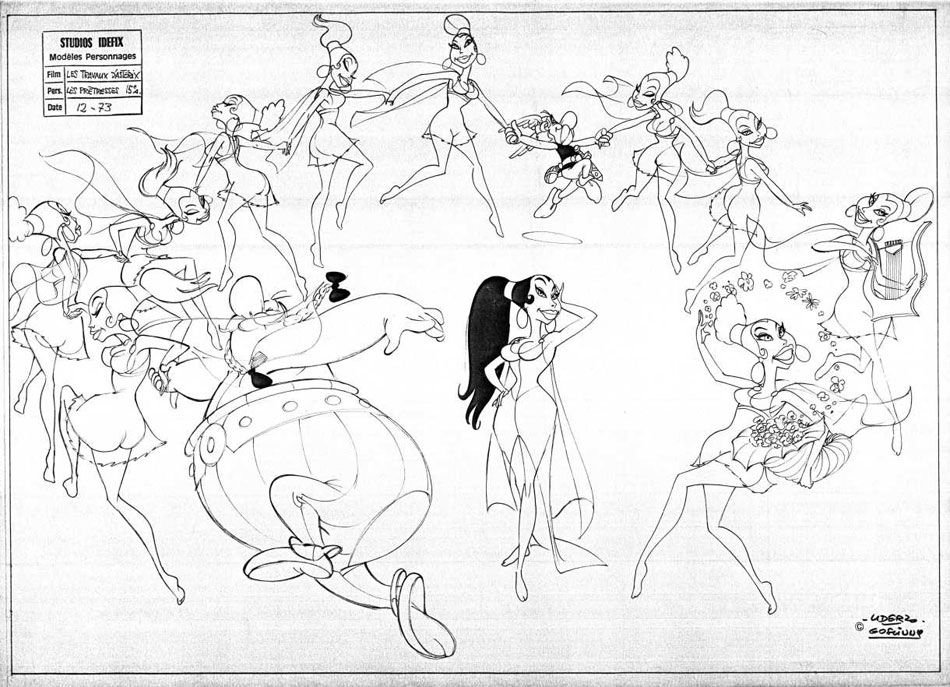

In 1974, Goscinny, Uderzo and their publisher Georges Dargaud established their own animation studio, Studio Idéfix. It was the first French animation studio since Paul Grimault's company. Several of its animators had been employees at Grimault, namely Henri Gruel, Pierre Watrin and Bernard Roseau. Their first feature film, 'Les 12 Travaux d'Astérix' ('Asterix and the 12 Tasks', 1976), was an exclusive story not based on a pre-existing 'Astérix' comic book. Uderzo came up with the idea to do something inspired by Hercules' 12 Tasks, which Goscinny developed into a witty screenplay. In the film, the Romans suspect the indomitable Gauls may be gods, since they are so invincible. Caesar therefore challenges Asterix and Obelix to 12 impossible tasks to prove this claim. One task, where the duo has to obtain "permit A38" from a Kafkaesque bureaucratic office, is regarded as a classic and even entered popular language in some parts of Europe, referring to similar frustratingly absurd bureaucratic problems.

Compared with previous 'Asterix' films and even the regular comics, 'Asterix and the 12 Tasks' had a far wackier plot, inspired by Tex Avery, with absurd gags that break the fourth wall and an ending that even breaks the regular continuity and historic events. At the time, the film polarized viewers, some of which felt it strayed too far from the spirit of the original comic. However, today the picture is a cult classic and regarded by many fans as the funniest 'Asterix' movie. Together with 'Asterix and Cleopatra', it has been regularly rebroadcast on European TV channels during holiday seasons. 'Asterix and the 12 Tasks' received an unofficial comic book adaptation, unavailable in the regular 'Asterix' series. This version was drawn by Uderzo's brother, Marcel Uderzo, and serialized in some European newspapers. Another version, published by Dargaud, was presented in the style of an illustrated storybook, with panels accompanying a written text. A third version, released in 1999, was also presented as an illustrated storybook, but with artwork directly based on Uderzo's original animation designs, readapted and streamlined for the book.

Model sheet for the animated film 'Les 12 Travaux d'Astérix' (1976).

It took nearly a decade before the next 'Astérix' picture came out: 'Astérix et La Surprise de César' ('Astérix Versus Caesar', 1985) was directed by Gaëtan and Paul Brizzi and combined the plots of 'Astérix and the 1st Legion' and 'Astérix the Gladiator' into a well-made, entertaining adventure movie. Pino Van Lamsweerde directed another 'Astérix' animated feature, 'Astérix Chez Les Brétons' ('Asterix and the Britons', 1986), which was a Danish-French co-production. One animator who worked on this film was Arthur Qwak, who also contributed to the Brizzi Brothers' next 'Astérix' picture, 'Astérix et le Coup du Menhir' ('Astérix and the Big Fight', 1989). While 'Asterix Chez Les Brétons' was well received, 'Astérix et le Coup du Menhir' wasn't. The film merged the plots of 'Astérix and the Big Fight' and 'Astérix and the Soothsayer', but wrote the "big fight" in the English translation of the title out of the movie. One of the animators who worked on the film was Jeff Baud.

'Astérix et les Indiens' ('Astérix Conquers America', 1994), directed by Gerhard Hahn, was the first French-German 'Astérix' film. The plot was a very loose adaptation of 'La Grande Traversée' (1975) and flopped. The same Astérix album also formed part of the plot of the next animated feature, 'Astérix et les Vikings' (2006), which was a Danish-French co-production, directed by Stefan Fjeldmark and Jesper Møller. The other half of the story was based on 'Astérix et les Normands' (1966). It received mixed reviews. Alexandre Astier and Louis Clichy made the Franco-Belgian feature 'Astérix: Le Domaine des Dieux' (2014), based on the comic book of the same name. It was the first Astérix film to be made in 3-D and received excellent reviews. Even Uderzo claimed it was the best adaptation he saw in his entire life. A new CGI film, 'Astérix: Le Secret de la Potion Magique' ('Astérix and the Secret Potion', 2018), followed four years later. Since 2021, new CGI-animated TV series have been created, for instance the spin-off 'Dogmatix and the Indomitables' (2021), and the Netflix series 'Asterix and Obelix: The Big Fight' (2025).

Since 1999, 'Astérix' has also been adapted into a successful but often critically mixed received series of live-action films: 'Astérix et Obélix Contre César' (1999), 'Astérix et Obélix: Mission Cléopâtre' (2002), 'Astérix aux Jeux Olympiques' (2008) and 'Astérix et Obélix: Au Service de Sa Majesté' (2012). In this film series, Gérard Depardieu plays an excellent Obélix. In 2023, a new live-action film with an original story was released, 'Asterix & Obelix: The Middle Kingdom', with Guillaume Canet as Astérix and Gilles Lellouche as Obélix.

'Astérix en Corse' ('Asterix in Corsica', 1973). This album, set in Corsica, was Uderzo's favorite.

Farewell to Goscinny

As 'Astérix' had become a huge commercial and critical success, Goscinny and Uderzo gradually dropped most of their other projects in favor of the indomitable Gauls. Their final new joint creation was the editorial strip 'Obélisc'h' (Pilote #172-186, 1963), in which the authors themselves appear with a present-day descendent of Obélix. After that, Goscinny and Uderzo's further collaboration was focused on the 'Astérix' stories and their animated spin-offs. Unfortunately, where money and success is concerned, conflict arises. The overnight success of 'Astérix' had made Goscinny the top dog at Pilote. In 1968, he clashed with a new generation of artists, resulting in editorial changes and Goscinny eventually stepping down as director. In 1974, he left the magazine altogether, ending the publication of 'Astérix' in Pilote's pages along the way. 'Astérix en Corse' ('Asterix in Corsica', 1973) was the final 'Astérix' story serialized in Pilote. The subsequent stories of the Uderzo-Goscinny tandem were first printed in newspapers like Le Monde, Sud Ouest, or in the weekly Le Nouvel Observateur, before appearing in book format at Dargaud. However, the relationship of Goscinny and Uderzo with their publisher Georges Dargaud took a turn for the worse. An escalating conflict over the comic's foreign rights prodded Goscinny to cut all ties with his publisher in the Autumn of 1977. A couple of months later, the legendary scriptwriter died from a heart attack at the early age of 51.

Les Éditions Albert-René

At the time of Goscinny's passing, Uderzo was halfway through drawing 'Astérix Chez Les Belges' ('Astérix in Belgium', 1979). The shock was huge and can be pinpointed in the story itself. In one scene, it starts raining and the sky never really clears up. In the final image of the story, a small rabbit can be spotted, walking away sadly. This was a reference to Goscinny and his wife, who often called each other "mon lapin" ("my bunny", pronounced as "lapaing", with a Nice accent). After 24 'Astérix' albums, the groundbreaking team-up between Goscinny and Uderzo had abruptly come to an end. However, by popular demand, Uderzo decided to continue the series on his own. In 1979, after the departure from Dargaud, he set up an imprint of his own. Its name, Les Éditions Albert-René, was in honor of the inseparable bond between the two friends.

Starting with 'Le Grand Fossé' ('Asterix and the Great Divide', 1980), Uderzo created eight new regular 'Astérix' albums entirely on his own, releasing them in irregular intervals. While graphically still impeccable and all instant bestsellers, critics felt that the new 'Astérix' albums never reached the same heights as under Goscinny's scripts, with the tone gradually becoming more child-oriented and melodramatic. The plausible reality of the original series was sometimes pushed too far into unbelievable fantasies, like a flying carpet in 'Astérix Chez Rahàzade' ('Astérix and the Flying Carpet', 1987) and Atlantis with flying animals in 'La Galère d'Obélix' ('Astérix and Obélix All At Sea', 1996). Uderzo's final album, 'Le Ciel Lui Tombe Sur La Tête' ('Asterix and the Falling Sky', 2005), felt like a frustrated attack aimed at his critics. It brought extraterrestrial aliens into the Astérix universe, combined with mean-spirited and pointless attacks at the manga industry, which had gradually conquered the European market. The book is widely perceived as the moment when the series finally jumped the shark. Some comic shops even strongly advised their customers not to buy it.

'Le Ciel Lui Tombe Sur La Tête' ('Asterix and the Falling Sky', 2005). The Superman lookalike is a caricature of Arnold Schwarzenegger.

Assistants

Throughout his career, Uderzo has often received assistance, most notably from his brother Marcel. From 1964 on, Marcel Uderzo inked three 'Tanguy et Laverdure' albums and, between 1965 and 1979, participated in the artwork of 16 'Astérix' stories. For the book publication of the first 'Astérix' story, page 35 was redrawn by Marcel as well, since the original source material was lost. Marcel also often colored the comics, because of Albert's colorblindness. In addition, he was responsible for a lot of promotional and other commercial artwork related to 'Astérix' for Éditions Dargaud. This included the rare album 'Les 12 Travaux d'Astérix' ("The Twelve Tasks of Astérix", 1976), based on the film of the same name, which never appeared in the regular series. Daniel Sebban was responsible for the lettering of 'L'Odyssée d'Astérix' ('Asterix and the Black Gold', 1981), and Michel Janvier provided the lettering of Uderzo's final three albums. Starting with 'La Galère d'Obélix' ('Asterix and Obelix All At Sea', 1996), Frédéric Mébarki was credited as Uderzo's inker, with Thierry Mébarki joining the team as colorist. However, the Mébarki brothers had been working with Uderzo since the 1980s.

Graphic contributions

In 1980, Uderzo provided illustrations for the Molière film adaptation 'L'Avare' (1980) by Jean Girault, starring Louis de Funès. When Hergé's 'Tintin' celebrated its 50th anniversary in 1979, Uderzo drew a graphic tribute, published in Tintin magazine. When the legendary 'Donald Duck' artist Carl Barks passed away in 2000, Uderzo drew a personal homage. In 2002, when Jean Roba's 'Boule et Bill' celebrated its 40th anniversary, Uderzo was one of several artists to draw a tribute, published in the magazine Sapristi!. After the death of Tibet in 2010, Uderzo also penciled a graphic "in memoriam".

Recognition

Albert Uderzo was honored with the title of Knight (1985) and Officer (2013) in the French Order of the Legion of Honor, and in the Netherlands he was named Knight in the Order of the Dutch Lion (2006). He received a Max und Moritz Preis (Germany, 2004), an Eisner Award (USA, 2005) and on 15 October 2009, an honorary doctorate from the university of Paris. Between 2003 and 2007, Albert Uderzo's own name inspired the Prix Albert-Uderzo, which were offered in three categories on behalf of Les Éditions Albert-René. In 2021, the Prix Albert -Uderzo were awarded again on the occasion of the Uderzo exhibition at the Maillol Museum in Paris.

Despite not being a Belgian comic, 'Astérix' has had its own comic book wall in Brussels since August 2005, located in the Rue de la Buanderie/Washuisstraat 15, as part of the Brussels' Comic Book Route. And despite not being Dutch, streets have been named after Asterix, Obelix and Idéfix in the Dutch city of Almere since 2003, as part of the "Comics Heroes" district.

In 1996, four asteroids were named after Astérix, Obélix, Idéfix and Panoramix. Uderzo also received his own asteroid in 2017.

Astérix: continuation

Regardless of the quality of the new 'Astérix' titles, each new book release was a major international media event. On 9 September 1998, Uderzo managed to obtain the profits and rights of the first 24 albums from his former publisher Dargaud in a trial. For a long time, he planned to let the franchise die with him, much like Hergé had done with 'Tintin'. Yet in 2008 he changed his mind. The shares in Les Éditions Albert-René of Albert Uderzo (40%) and the daughter of René Goscinny, Anne (20%), were sold to the publishing house Hachette. Uderzo's daughter Sylvie held on to her 40% of the shares, as she strongly disagreed with her father's decisions of having the series continued after his retirement. The rift between father and daughter had begun in 2007, when Sylvie Uderzo and her husband Bernard de Choisy were dismissed as managers of the Uderzo estate. A painful legal battle followed, that lasted for seven years. In 2014, father and daughter reconciled, stating they were "determined to make a clean slate reciprocally, with regard to the reproaches made by both sides".

In the meantime, Uderzo had been searching for a capable writer and artist to safeguard the continuation of 'Astérix'. In 2011, Jean-Yves Ferri was presented as the writer of the next 'Astérix' album. Originally, Uderzo's longtime assistant Frédéric Mébarki was considered as the new artist, but he got cold feet and backed out. Instead, a suitable replacement was found in Didier Conrad, an artist with already an impressive track record in Franco-Belgian comics. In October 2013, the first Ferri-Conrad book appeared, 'Astérix Chez les Pictes' ('Astérix and the Picts'). Since then, new 'Astérix' albums have been published almost every other year. In 2023, Fabcaro came on board as the comic's new scriptwriter.

In 2016, Hachette launched Astérix Max!, a magazine appearing twice a year. In 2019, a German-language Astérix magazine was launched by Egmont, called Astérix Magazin. On 1 April 2020, an online 'Asterix' magazine was launched, 'Irréductibles avec Astérix', which could be downloaded for free at www.asterix.com during the COVID-19 pandemic. Coinciding with the release of the animated TV series 'Idéfix et les Irréductibles' ('Dogmatix And The Indomitables', 2021), a spin-off comic series of the same name was launched by Hachette/Les Éditions Albert-René, starring short stories with Obélix's dog Idéfix. Among the contributing writers have been Jérôme Erbin, Matthieu Choquet, Yves Coulon, Hervé Benedetti, Nicolas Robin, Michel Coulon, Simon Lecocq, Marine Lachenaud, Olivier Serrano, Cédric Bacconnier, Jean-Marie Olivier, Lison D'Andréa and Philippe Clerc, with Philippe Fenech, Jean Bastide and David Etien as artists.

Final years and death

In 2015, Uderzo suddenly gave a sign of life again when the head office of the French satirical magazine Charlie-Hebdo became the victim of a terrorist attack. One of the casualties was his friend Cabu. Enraged by the events, Uderzo drew two cartoons in tribute to the murdered cartoonists. The first drawing shows Astérix beating up a terrorist flying out of his sandals, while shouting "Me too, I'm a Charlie", referencing the "Je Suis Charlie" solidarity movement that spontaneously rose to defend the freedom of speech. A more solemn drawing followed soon after, with a mourning Asterix and Obelix putting a rose on the ground. Uderzo even proposed selling one of the original pages of 'Les Lauriers de César' ('Asterix and the Laurel Wreath') with the money going to the families of the victims.

In the night between 23 and 24 March 2020, Albert Uderzo passed away in his home in Neuilly-sur-Seine. He was 92 years old. As one of the last remaining legends of Franco-Belgian comics, his death made international headlines. Since his passing happened to coincide with several Western countries going into a lockdown because of the COVID-19 pandemic, several articles mistakenly reported he had died from the coronavirus. In reality, Uderzo died from a heart attack. French president Emmanuel Macron paid tribute in a personal speech, citing "the ink in which Uderzo dipped his pen to draw was the real magic potion."

Cover illustration for the 'Astérix' album 'La Grande Traversée' ('The Great Crossing').

Legacy, celebrity fans and cultural impact

'Astérix' is one of the most recognizable French symbols on the planet, along with baguettes, wine and the Eiffel Tower. When Time Magazine devoted an article to "The New France" in 1991, it was visualized by Asterix on the cover. The tiny Gaul has become the French equivalent of Mickey Mouse, particularly since he also has his own theme park near Paris since 1989, the Parc Astérix. The series garnered some notable celebrity fans over the years. According to French politician François Misoffe, president Charles De Gaulle read 'Astérix' and once named members of his cabinet after characters from the comic. De Gaulle's successor Georges Pompidou once suggested sending Astérix to Switzerland, which eventually led to the album 'Astérix Chez Les Helvètes' ('Asterix in Switzerland', 1970). When France launched its first satellite in 1965, it was officially named A-1, but later renamed to the 'Astérix'.

Astérix: parodies

As world famous as Astérix is, parody is inevitable. In 1971, two German 'Asterix' spoofs, 'Asterix un die SDAJ' and 'Asterix und der Kampf der Lehrlinge', were published, making propaganda for the Socialist German Workers Youth. In 1978, a politically motivated parody about nuclear energy was published in Austria under the title 'Asterix und das Atomkaftwerk', which was further bootlegged in various languages. The book, credited to G. Raub and U. Druck, was mostly a cut-and-paste work, cobbling together scenes from existing 'Asterix' albums. In 1981, and again in February 1984, the Viennese publisher was sued by Uderzo's estate for plagiarism. Raub and Druck also published 'Asterix & Obelix gegen Rechts' (1981), in which the Gauls were pitted against conservative German politician Franz Jozef Strauss.

Other German 'Asterix' parodies reacted against the university system 'Asterix und die UNI' (1979), Turkish holidays ('Asterix und Obelix reisen in die Türkei', 1979), hotel Schwarzwaldhof ('Asterix im Schwarzwaldhof',1980), nuclear missiles ('Asterix im Bombenstimmung' and 'Asterix und die Atombombe', published in 1981 by Raternal Verlag), reductions of subsidies ('Asterix und die Subventionskürzungen', 1980), reductions of the 35-hour week ('Asterix und Obelix und die 35-Stunden-Woche', 1980), holiday villages ('Asterix im Hüttendorf', Waldgeist,1981, by Rosa Klar and Bernd Trueb), prisons ('Asterix im Knast', 1981), cultur centers ('Asterix und Obelix. Das Kulturzentrum', 1986), yuppies ('Asterix als Yuppie', Madnight Oilie, 1993) and the Northern-Irish conflict ('O'Connerix in Nordirland', D.A & D.A., 1999). Some German 'Asterix' spoofs were promotional in nature, for instance for the student group Liste Asta und Fachschaften ('Wahl-ASTAR-Rix', 1979), the punk movement ('Alkoholix und der Jutesack' and 'Alkoholix gegen Superman', both in 1983), the environmental youth organization Naturfreundejugend ('Asterix bei der NFJ', 1984) and the 'Monsters of Rock' festival ('Asterix auf dem Monsters of Rock', 1989). Equally odd were 'Gallas: Skandal auf der Chewing-Ranch' (Egmont Ehapa, 1983), which spoofed the soap opera 'Dallas', and 'Astronix der Galliroider' (1990) by a certain Alex, which brought the Gaul into outer space. The two-parter 'Asterix und die grosse Mauer' (Piraten Comics, 1992) was also translated into French as 'Astérix et la Grande Muraille' (Kalashnikov, 2002). The spoof 'Der Q-Seher' (1994) was credited to Gehtfix, Hilftfix, Adelnix (script) and Geklaut (art). 'Asterix und der Faseroptische Kreisel' (1997) dealt with fibre-optic gyroscopes, and 'Die Verschwörung' (1998) delved into conspiracy theories. The political satire 'Asterix und der Kampf um's Kanzleramt' (2005) revolved around the German chancellor elections.

In France, Asterix fought against the French electricity company EDF in 'Astérix Contre L'Empire de Framatum' (1980). In the Netherlands, the squatters' movement brought out 'Asterix en het Kraakpand' (1980), while in J. de Reuver's 'Faberix en de Kruisraket' (1983), the indomitable Gauls resisted against the placement of nuclear missiles. In Belgium, the anti-cigarette spoof, 'Anti-rook-kolder-stripke: Asterix en de Xgaretten' (1991), was made. In the United Kingdom, Asterix promoted the shop Pick 'n' Pay in 'Asterix Goes Shopping at Pick 'n' Pay' (Hodder & Stoughton, 1986) and fought against bulldozers in 'Asterix and the Road Monster' (1990). Spanish Asterix parodies were 'Asturix y Obierzix Van A Bankistan' (2012), 'La Hoguera Calderón de la Barca' (1999), 'Asterix Contra Las Privatizaciones' (2005), 'Asterix e la Battaglia di Venaus' (No Tav, 2005), 'Asterix e la Tregua Olimpica' (No Tav, 2006), 'Asterux in Baetica' (2008), 'Asturix in Brunete' (2008) and 'Iut Bayonne' (2014). A Hungarian spoof is 'AZ Asterix-Legenda' (2013). Danish artist Freddy Milton made a political satire, 'Svenderix og de gæve Danere' (2013), spoofing Danish politician Svend Auken.

Predictably, 'Asterix' also inspired pornographic parodies, of which AVE's 'Asterix Op De Walletjes' (1982) and 'Asterix de Geilaard' (1982), and 'Rammérix - Le Condôme' (also known as 'La Vie Sexuelle d'Astérix') by Ger van Wulften's Espee team (including Willem Vleeschouwer and Wim Stevenhagen) are the most notorious. In 1983, Dutch stores were forced to give up their stock of pornographic or otherwise illegal 'Asterix' comics by legal order. This also ended the market and desire to create more similar spoofs, at least in the Netherlands. In the same category, there are the German sex parody 'Österix und der Tempel der Elektra' (1984), the French 'Le Dépucelage d'Astérix' (Fluide Thermal, 2009) by Almo and the French 'Camille la Zadiste' (2012).

More inspired 'Astérix' sex parodies appeared in Roger Brunel's 'Pastiches 1' (1980), Alain Voss' 'Parodies de Al Voss' (1984), 'Les Invraisemblables Aventures d'Istérix' (1991) by Coyote, Denis Merezette and Michel Rodrigue and 'Asterix Le Gaulois' (Yop Comics, 2011), drawn in a realistic style by Chris Lannes. Nevertheless, in 1983 Uderzo wanted to sue Brunel, but couldn't, since his pastiche was recognized as a parody by French law. Instead, he did the next best thing and managed to get a German translation of Brunel's comic by Volksverlag off the market. 2,000 copies were confiscated.

Sticker series for Agfa Film, 1992, made at the occasion of the Treaty of Mastricht, to celebrate the then-12 European union members. Depicted above are the United Kingdom (with an appearance by Notax), The Netherlands, Greece and Ireland.

Influence and plagiarism

'Astérix' is one of the most influential humorous history comics in the world. Sometimes, this has led to downright plagiarism, for instance comic series that didn't use Uderzo's characters, but were obviously similar in terms of content, characters and jokes. After losing his license to the 'Asterix' stories, the German publisher Rolf Kauka came up with his own rip-off, titled 'Fritze Blitz und Dunnerkiel' (1967-1969), scripted by Peter Wiechmann and drawn by Branco Karabajic and later Riccardo Rinaldi. The stories were set in ancient Germany, with the title characters being Goths. Goscinny sued, but the judge ruled in Kauka's favor. Nevertheless the series wasn't a success and already ended in 1969. Two decades later, the Austrian cartoonist Günther Mayrhofer's 'Gallenstein' was another rip-off, this time set in the 16th century. Even the costumes of his characters look Celtic rather than the era they are supposed to take place in. Uderzo filed a complaint and the series was discontinued. In Greek, Dimitris Antonopoulos' 'The Ancient Losers' ('Ta Koróida oi Archaíoi') was a satire of Greek mythology, copying lots of imagery from 'Asterix'.

Besides obvious plagiarism, the 'Astérix' series has influenced many other humorous-satirical series set in national history featuring characters fighting a military oppressor. Among them are Lo Hartog van Banda and Dick Matena's 'De Argonautjes' (set in ancient Greece), Romano Garofalo and Leone Cimpellin's 'Alem' (set in Italy during the Antiquity), Lazo Sredanovic's 'Dikan' (set in 6th-century Balkan), Tito and José Maria André's 'Tonius' (set in medieval Portugal when the Moors occupied the Iberian peninsula), Janusz Christa's 'Kajko and Kokosz' (set in medieval Poland), Hanco Kolk and Peter de Wit's 'Gilles de Geus' (set in 16th-century Netherlands) and Dwi Koendoro's 'Sawang Kampret' (set in 17th-century Indonesia). The Dutch artist Peter de Smet made 'Morgenster en Durandel' (1984-1985), of whom the title characters were similar to Astérix and Obélix, while all action is set in a post-apocalyptic world. The Belgian humor comic 'Arkulleke' (scripted by Hugo Renaerts and drawn by Frank Sels, 1968) was set in ancient Rome, also showing notable graphic inspiration from 'Astérix'. Again in the Netherlands, the historical comic series 'De Romeinen' (2023- ), written by Kristof Berte and drawn by Tim Artz and Irene Berbee, shares a lot with 'Astérix' in terms of humor and atmosphere.

It has all gotten to the point that whenever a humorous depiction of ancient Gaul is used in historical comics, writers and artists unavoidably use visual cues from the 'Astérix' series. Even if they deliberately try to avoid it, readers will subconsciously still think of 'Astérix'.

Homages

Uderzo has been praised by veteran artists René Pétillon, Moebius, André Franquin and Gotlib. In 1996, the comic book 'Uderzo Croqué Par Ses Amis' (1996) featured homages to Uderzo by 26 authors, namely Achdé, Éric Adam, Arleston, Serge Carrère, Giorgio Cavazzano, André Chéret, Hélène Cornen, François Corteggiani, Al Coutelis, Crisse, Xavier Fauche, Franz, Gil Formosa, Paul Claudel, Michel Janvier, Erik Juszezak, Jean-Charles Kraehn, Jack Manini, Félix Meynet, Jean-Louis Mourier, François Plisson, Rodolphe, Michel Rouge, Éric Stalner, Pierre Tranchand and Roger Widenlocher. Another all-star homage, called 'Astérix et ses Amis - Hommage à Albert Uderzo' was released in 2007, and contained contributions by international authors like Achdé, Scotch Arleston, Baru, Batem, Fred Beltran, François Boucq, Brösel, Serge Carrère, Raoul Cauvin, Steve Cuzor, Dany, Derib, Emebé, Forges, Laurent Gerra, Jean & Philippe Graton, Juanjo Guarnido, Kathryn & Stuart Immonen, Jidéhem, Henk Kuijpers, Laudec, David Lloyd, Loustal, Milo Manara, Midam, Jean-Louis Mourier, Grzegorz Rosinski, Didier Tarquin, Tibet, Turf, Jean Van Hamme, William Vance, Vicar, François Walthéry and Zep.

In 2019, to celebrate the 60th anniversary of the franchise, no less than two 'Astérix' homage albums were launched. In Germany, '60 Jahre Asterix' (2019) featured old and new graphic contributions by Didier Conrad, Flix, André Franquin, Klaus Jöken, Mawil, Moebius, Fabrice Tarrin and Sascha Wüstefeld. In France, 'Générations Astérix' (2019) has more than 60 graphic homages, including again by François Boucq, Didier Conrad, Derib, Flix, Juanjo Guarnido, Milo Manara, Mawil, Midam, Fabrice Tarrin and Sacha Wüstefeld, but also Charlie Adlard, Pierre Alary, Kaare Andrews, Laurent Astier, Philippe Aymond, Alain Ayroles, Alessandro Barbucci, Béja, Charles Berberian, Philippe Bercovici, Blutch, Paul Cauuet, Florence Cestac, Frank Cho, Ian Churchill, Serge Clerc, Louis Clichy, Cosey, Arthur De Pins, Delaf, Guy Delisle, Dupuy, Jean-Yves Ferri, Emmanuel Guibert, Eric Hérenguel, Frédéric Jannin, Kim Jung Gi, Wilfrid Lupano, Frank Margerin, Julie Maroh, Catherine Meurisse, Ralph Meyer, Félix Meynet, Terry Moore, Fabrice Parme, Pascal Rabaté, François Ravard, Anouk Ricard, Mathieu Sapin, Lolita Séchan, Tébo, Didier Tronchet, Lewis Trondheim, Tony Valente, Sylvain Vallée, Valérie Vernay and Bastien Vivès.

Influence

In France, Albert Uderzo was a strong graphic influence on Nicolas Barral, Ian Dairin, Désert, Françoise Mouly, Jean Mulatier and Frédéric Toublanc. He also found followers in Austria (Günther Mayrhofer), Belgium (Kristof Berte, Jeroen De Coninck, Willy Lambil, Merho, Erik Vandemeulebroucke), Finland (Kari Korhonen), Germany (Andreas Schuster), Greece (Dimitris Antonopoulos), Italy (Leone Cimpellin), The Netherlands (Rim Beckers, Gleever, Koen Hottentot, Hanco Kolk & Peter de Wit, Marcel Ozymantra, Marnix Rueb, Ronald Sinoo, Peter de Smet and Willbert van der Steen), Poland (Janusz Christa), Portugal (José Maria André), Romania (Robert Obert), Serbia (Lazo Sredanovic), Spain (Tony Fernández, José Antonio González, Juanjo Guarnido, Tito) and The United Kingdom (Adam Weller).

Outside of Europe, 'Astérix' also has his notable fans. In North and South America, Goscinny and Uderzo are admired in Argentina (Liniers, Fernando Sosa), Brazil (Rodolfo Damaggio, Harald Stricker), Canada (Gisèle Lagacé), Costa Rica (Alex Corrales) and The United States (Alexis Fajardo, Tessa Hulls). Illustrator Edward Gorey was a fan of 'Astérix', even owning rare English-language translations of 'Oumpah-Pah'. When he was interviewed for Proust's Questionnaire in 1997, he named 'Astérix' one of his favorite names. Matt Groening is also an 'Astérix' fan. The travel episodes in 'The Simpsons', in which the family visits a certain country with various references to the things that nation is famous for, are directly inspired by the similarly multi-layered travel-themed albums of 'Astérix'. Other notable Uderzo fans across the globe can be found in India (Harsho Mohan Chattoraj) and South Africa (Zapiro).

Books about Albert Uderzo

For those interested in Uderzo's life, the biographies 'Uderzo: de Flamberge à Astérix' (Éditions Albert-René, 1985), 'Uderzo-Storix' (J.-C Lattès, 1991) by Bernard de Choisy and 'Uderzo' (Chne, 2002) by Alain Duchêne are all very much recommended.

Traditional festivities at the end of 'Astérix et le Chaudron' ('Astérix and the Cauldron').