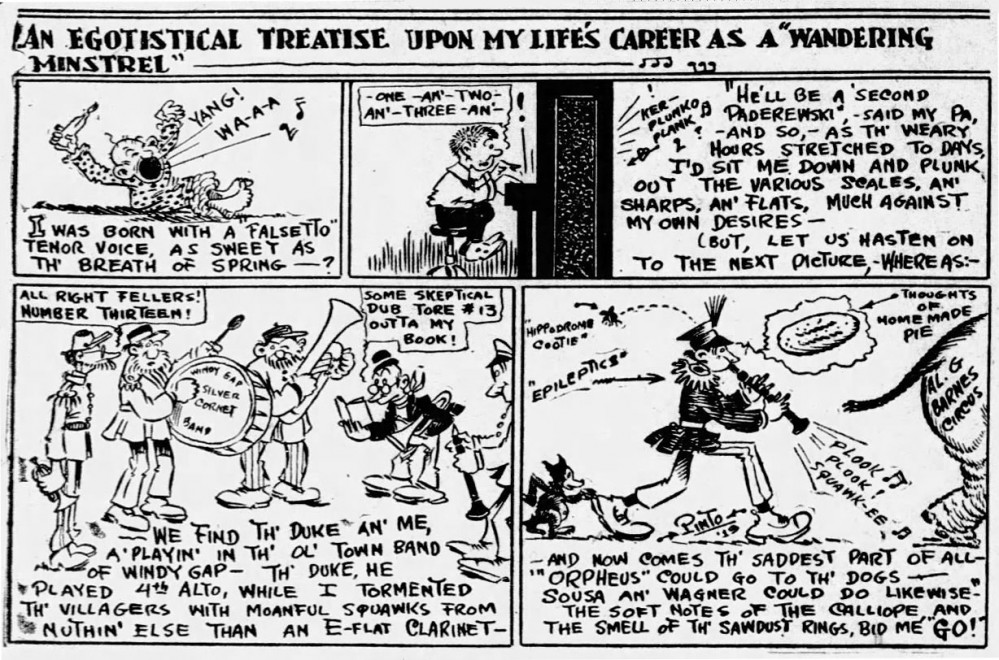

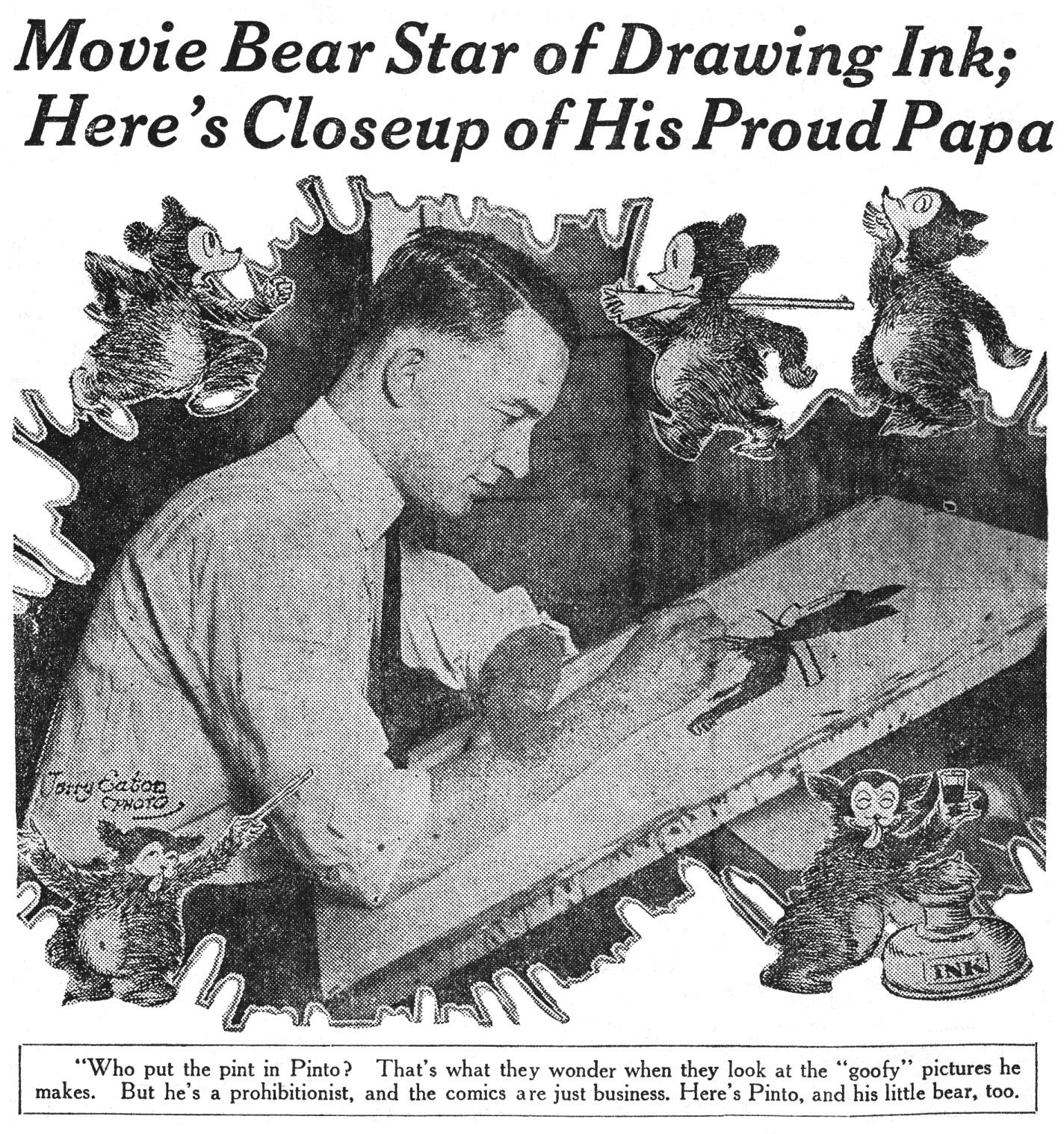

Autobiographical comic strip for the San Francisco Bulletin (22 October 1919).

Pinto Colvig was an early 20th-century American clown, who became world famous as the original voice of the Disney character Goofy. Colvig found additional fame as the first actor to perform Bozo the Clown. A creative dynamo, he was active in many fields, including as clarinetist, actor, animator and newspaper cartoonist. Most of his cartoons were single-panels, including the short-lived 'Life on the Radio Wave' (1922) series in The San Francisco Chronicle, though he made occasional use of sequential comic strip panels.

Early life

Vance DeBar Colvig was born in 1892 in Jacksonville, Oregon, as the son of an attorney. Colvig's father William was nicknamed "Judge Colvig", but in reality he never had that profession. Pinto Colvig grew up in a large family, with six other siblings. To gain attention, he became an entertainer. He pulled goofy faces, played pranks and imitated sound effects. Because of his freckled face, he was nicknamed "Pinto", in reference to the horse breed known for white patches on its skin. As a twelve-year old in 1904, Colvig already earned money as a clown. One day, when he visited the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition in Portland, he told a local vaudeville performer that he could play the clarinet. After rushing home to fetch his instrument, Colvig showed how he could produce funny sounds while making silly faces, and was instantly hired as a circus attraction. From that moment on, Colvig combined his school work with performing at vaudeville shows, carnivals and circuses.

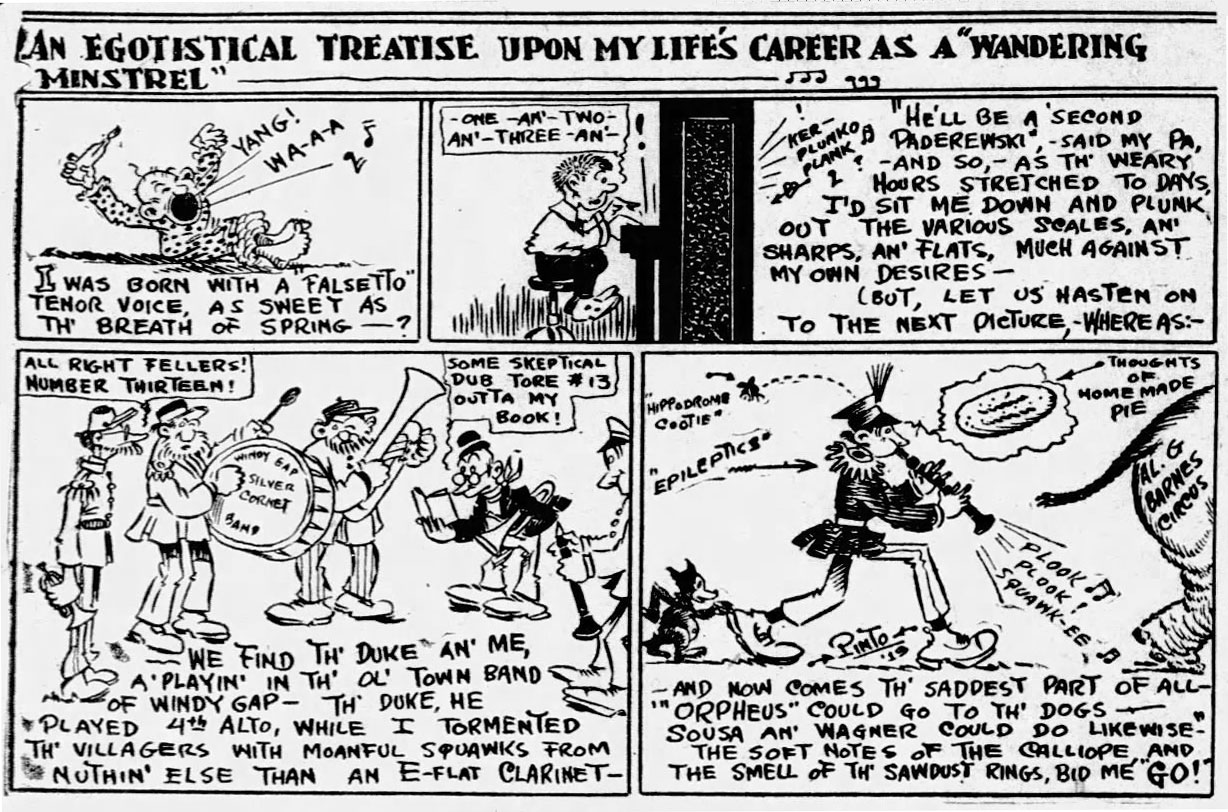

Cartoon depicting the cartoonist's father, "Judge" Colvig, for the Medford Mail Tribune (19 September 1910).

Between 1913 and 1915, Colvig toured with the Al G. Barnes Circus and the Ringling Brothers. It left him with little time for school and he dropped out of sixth grade. Through a statute as "special student", he was still able to go to high school. Between 1910 and 1913, he studied art at the Oregon Agricultural College in Corvallis, but only for five hours a week. In his spare time, he drew cartoons for the college newspaper, The Oregon Agricultural College Barometer, and their yearbook. Again Colvig's stage career took up most of his time. When a history teacher asked him to study ancient history on top of his weekly five hours of art class, the pupil was too polite to refuse. Nevertheless, Colvig barely attended the class and on the day of his exam, he simply drew cartoons of Greco-Roman historical characters and turned them in. In the spring of 1913, he dropped out of high school for good.

Colvig made a living as a vaudeville performer, touring with circuses and performing his "silly clarinet player" act. He also performed with a chalkboard, drawing funny pictures while chatting with the audience. Although he loved circus life, the troupes usually didn't perform during winter time. Left without a job during these periods, Colvig searched for other ventures. Between the 1900s and 1922, he earned extra income as an animator and newspaper cartoonist. In 1922, he moved to Hollywood. He had a recurring role as butler in live-action movie adaptations of Richard F. Outcault's newspaper comic 'Buster Brown', namely the shorts 'Buster Be Good' (1925), 'Oh! Buster!' (1925) and 'Buster's Nightmare' (1925). From 1926 on, Colvig was a gag writer and cartoonist for Mack Sennett's slapstick movies. He also drew the title cards for these pictures, adding cartoony drawings.

Newspaper cartoons

According to a letter written by Colvig to The Jacksonville Sentinel, dated 31 August 1962, he published his earliest newspaper cartoons in the 1900s, for this aforementioned paper and its comic supplement, Tanglefoot. One time, as a joke, each page had a dead fly stuck on it. Colvig had literally caught a whole fruit jar full with these insects to make this joke work. Readers who bought the paper that day were informed that Tanglefoot was now a literal "fly-leaf". In 1910-1912, Colvig also drew cartoons for The Medford Mail Tribune. On 5 September 1914, he joined the local paper The Nevada Rockroller in Reno, Nevada. From 14 September on, his caricatures also appeared in The Sunday Oregonian. His work could additionally be found in The Reno Rock-Crusher, a political paper that was discontinued once the publisher was diagnosed with smallpox. By late 1914, Colvig's cartoons appeared in the Carson City Daily News.

Colvig's cartoons were mostly one-panel cartoons and caricatures based on current events. As a running gag he often added a little horse in the background. This character, nicknamed "Pinto's Nightmare", provided humorous commentary to the events in his drawings. Throughout most of the 1900s and early 1910s, Colvig's cartooning career was mostly a pastime whenever the Al G. Barnes Circus troupe was out of town or put on temporary hiatus, usually during the winter period. He didn't look down on his profession, though. To him a cartoonist was "just a clown with a pencil". It took until his marriage (1916) and especially when he and his wife had children, before Colvig settled down. Leaving his days as a travelling vaudeville/circus comedian behind, he now became a full-time animator and newspaper cartoonist. Between 5 March 1919 and February 1920, he had his own illustrated column in The San Francisco Bulletin, titled 'The Bulletin Boob'. He interviewed Hollywood stars and printed their conversations in the paper.

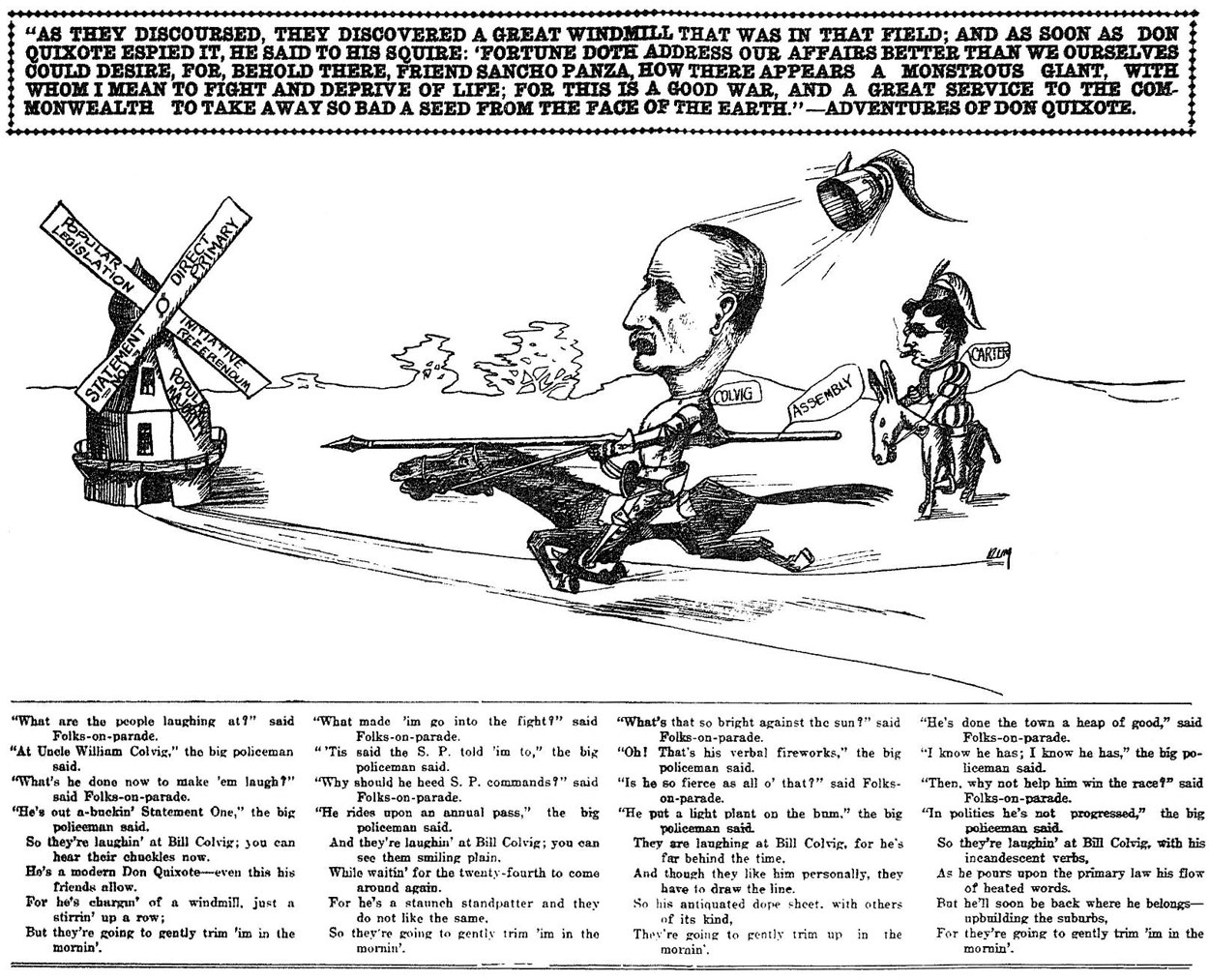

'Life on the Radio Wave'.

Life on the Radio Wave

In the early 1920s, radio was still a young medium, but slowly but surely attracted a mass audience. Many magazines and papers felt the need to offer a special column devoted to daily broadcasts and news about radio personalities. On 19 March 1922, the San Francisco Chronicle launched a one-panel cartoon series, 'Life on the Radio Wave', syndicated by United Features, to liven up their radio pages. 'Life on the Radio Wave' was drawn by Colvig, using the pen name Pinto, and appeared three to four times a week. The series had no recurring characters. Instead it focused on radio listeners in general. Some are so enthralled that they forget or ignore their surroundings. Others take the broadcasts so seriously that they forget they aren't real or that other people have no clue what they are talking about. Some gags depict people trying to find the right radio signal or building their own radio sets. According to Allan Holtz of the Stripper's Guide blog, 'Life on the Radio Wave' ended on 26 August 1922. Around that same time, Colvig had moved to Hollywood, motivated by the interviews he had with actors for the paper.

As short-lived and gimmicky 'Life on the Radio Wave' may have been, it nowadays offers an interesting historical look. It shows how big the impact of this medium was on general audiences in the decades before other mass media, like television, made their mark.

Article about Pinto Colvig, San Francisco Bulletin, 24 May 1922.

Animation

In 1916, Colvig worked as an animator for the Animated Film Corporation in San Francisco. Although this studio is nowadays forgotten and most of their content lost, they did produce early examples of a feature-length animated cartoon ('Creation', 1915) and a color cartoon ('Pinto's Prizma Comedy Review', 1919). After his move to Hollywood in 1922, Colvig worked for Walter Lantz. He is credited with the design of one of his earliest characters, Bolivar the Ostrich. In 1928, Lantz was assigned to produce 'Oswald the Lucky Rabbit' cartoons. Colvig also worked on theatrical shorts starring this character, originally created by Walt Disney and Ub Iwerks, who didn't own his rights.

Disney

In 1930, Walt Disney had become the market leader in animation. Colvig applied for a job as cartoon writer, voice actor and provider of sound effects. He co-scripted the 'Mickey Mouse' cartoons 'Mickey's Revue' (1932), 'The Whoopee Party' (1932), 'Touchdown Mickey' (1932), 'The Klondike Kid' (1932), 'The Steeple-Chase' (1933) and 'Mickey's Amateurs' (1937) and the Silly Symphony shorts 'Three Little Pigs' (1933), 'The Grasshopper and the Ants' (1934), 'The Cookie Carnival' (1935), 'Music Land' (1935), 'Broken Toys' (1935) and 'Merbabies' (1938). Together with Erdmann Penner and Walt Pfeiffer, Colvig also co-directed one Mickey Mouse short, 'Mickey's Amateurs' (1937), in which Mickey, Donald Duck and Goofy host a stage show, broadcast on the radio. In the same cartoon, Colvig provided Pete's singing voice.

Colvig made significant contributions to 'The Three Little Pigs' (1933). Apart from being co-writer, some sources have also credited him with co-writing the lyrics to Frank Churchill and Ann Ronnell's hit song 'Who's Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?'. He also voiced the Practical Pig who made his house from bricks. In one scene, Colvig also originally briefly voiced the Big Bad Wolf when he disguises himself as a door-to-door salesman. In the original 1933 theatrical cut, the Wolf pretended to be a representative of the Fuller Brush Company. He had a stereotypical Jewish look, complete with thick glasses, a gag nose, black beard and Yiddish accent. After World War II, the segment was altered to avoid unfortunate anti-Semitic undertones. The Wolf no longer wears a stereotypical Jewish mask, but simply put on some glasses. Colvig's accent-heavy voice was rerecorded by Disney sound effect maker Jimmy MacDonald, using different lines and vocal inflections.

Still from 'The Grasshopper and the Ants', 1934, © Disney.

Colvig also voiced the grasshopper in Disney's 'The Grasshopper and the Ants' (1934). Much of the insect's vocal mannerisms, including his theme song, 'The World Owes Me A Living', were later reused for Colvig's signature character Goofy. Colvig played the heroic gingerbread man in 'The Cookie Carnival' (1935) and the dwarfs Sleepy and Grumpy in 'Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs' (1937). He was also the earliest actor to make the barking sounds for Mickey's dog Pluto. Animal sounds were Colvig's expertise, proven by the ants in the Donald Duck cartoons 'Tea For Two Hundred' (1948) and 'Uncle Donald's Ants' (1952), as well as the flamingo in 'Alice in Wonderland' (1951). Among his recurring animal characters were Salty the Seal in three Mickey Mouse cartoons and the crazy Aracuan Bird who heckles Donald Duck in 'The Three Caballeros' (1944), 'Clown of the Jungle' (1947) and 'Melody Time' (1948). Colvig did a convincing impression of Hollywood comedian W.C. Fields in 'Broken Toys' (1935). Colvig's hiccup sounds were often recycled, for instance for Hortense the Ostrich in 'Donald's Ostrich' (1937) and Dopey in 'Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs' (1937). The same applied to his screaming sounds, memorably evoked by Ichabod Crane in 'The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad' (1949) and Thunderclap the Moose in 'Morris, the Midget Moose' (1950). He also played the goons of Maleficent the Witch in 'Sleeping Beauty' (1959). Since Colvig's voice sounds somewhat similar to another well-known Disney voice actor, Sterling Holloway, they are sometimes confused with one another.

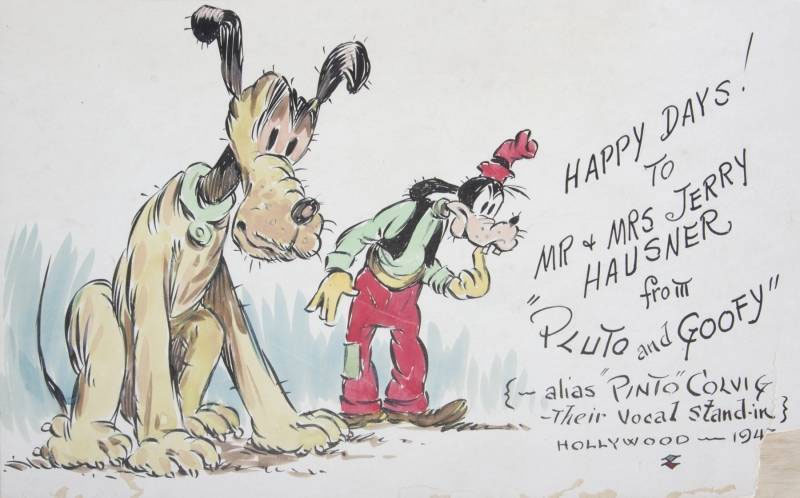

Pluto and Goofy, drawn by Pinto Colvig.

Goofy

Colvig's most significant and longest-lasting contribution to the Walt Disney Studio was done as the first voice actor of Goofy. The character debuted as "Dippy Dawg" in the Mickey Mouse short 'Mickey's Revue' (1932), directed by Wilfred Jackson. He looked very old, due to glasses and a beard, and only had a minor role as a spectator with an annoying laugh. Colvig based the voice on a young flagman he once observed at a railroad crossing in Oregon. Interviewed by Jake Rachman for the Omaha World Herald (9 April 1944), Colvig described him as "one of those big bucolic youths of the village or crossroads who have no particular aim in life beyond cracker barrel conferences or cutting their initials in the hitching post in front of the general store." Colvig had previously also used the voice for his vaudeville character "The Oregon Appleknocker".

The character was redesigned by animator Tom Palmer, Art Babbitt and Frank Webbe for his second screen appearance in 'The Whoopee Party' (1932). Now he received a clean shaven face and trademark fedora hat. He was renamed Goofy and developed into a laughable but loveable simpleton. His proverbial stupidity was similar to Stan Laurel, while the baggy pants and huge shoes brought up comparisons with Charlie Chaplin. Goofy became a recurring character in many 'Mickey Mouse' cartoons of the 1930s. From 'Orphan's Benefit' (1934) on, he and another new star, Donald Duck, often teamed up with Mickey. The happy mouse was already creatively limited, since parents complained whenever he did something family unfriendly. Donald's temper tantrums and Goofy's clumsiness could now steal the show, while Mickey was regulated to the role of straight man.

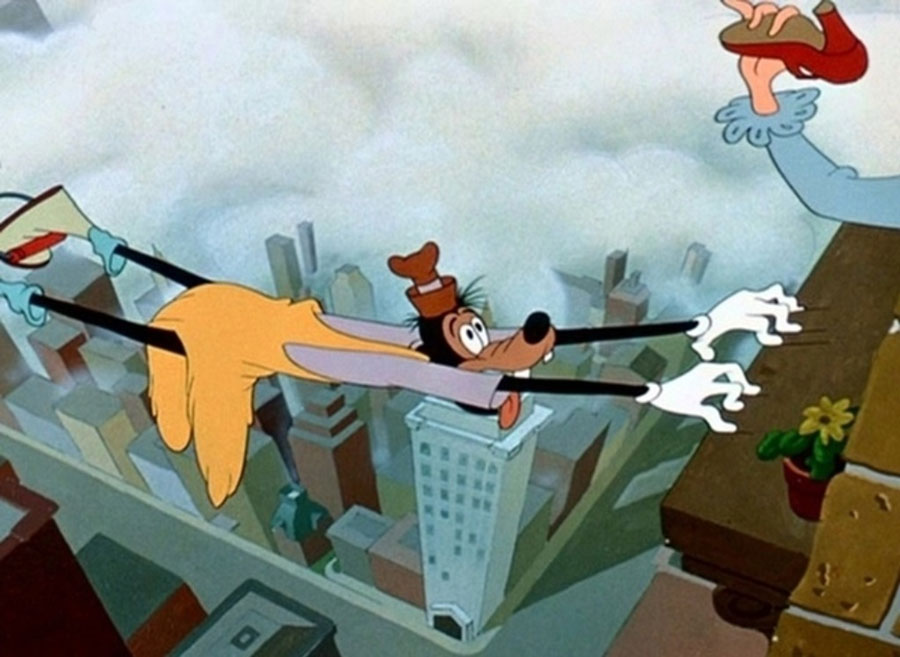

Still from 'Goofy Gymnastics' (1949). ©Disney.

However, in 1937 Colvig left Disney after a never-specified falling out. Since he didn't own the rights to Goofy, the company kept using the character. In fact, starting with 'Goofy and Wilbur' (1939), Goofy received his own solo series. Since his voice wasn't that difficult to imitate, Danny Webb succeeded Colvig as Goofy's voice actor. But most of the time new dialogue wasn't needed, because his cartoons relied on visual comedy. In a master stroke, Goofy was recast as an enthusiastic amateur sportsman. From the short 'How to Ride a Horse' (1941) on, the clumsy dingo tried out various hobbies and sports with disastrous results. Several rank among the funniest Disney cartoons ever made. Most of the dialogue is provided by a narrator, whose serious voiceover offers a hilarious contrast with Goofy's ill-fated attempts to master a certain game or activity. It also allowed the character to remain mostly silent. Whenever he had to say something, sound technicians simply used archive recordings of Colvig chuckling, singing, yelling or saying "Gawrsh" or "Somethin's wrong here." Only one stock sound effect was brand new and not invented by Colvig: the famous "Goofy holler". This high-pitched yell is heard whenever Goofy falls down from a great height, and was introduced in the cartoon 'The Art of Skiing' (1941) and recorded by Austrian skier and yodeler Hannes Schroll. It's arguably one of the most iconic Hollywood soundbites, along with Johnny Weissmuller's Tarzan yell, Woody Woodpecker's laugh, Godzilla's roar and the Wilhelm Scream.

In 1941, Pinto Colvig returned to Disney and remained Goofy's official voice until he passed away in 1967. Even during this period, he only occasionally had to record new lines. But he contributed much to the character's popularity.

Goofy in comics

In addition to the cartoons, Goofy became a regular character in Disney comic stories, usually as a sidekick to Mickey Mouse. If he played a starring role, it was always in short gags or humorous short stories. In 1949, Goofy received a sidekick of his own, Ellsworth the mynah bird, created by Bill Walsh and Manuel Gonzales. In 1965, Del Connell and Paul Murry reimagined Goofy as a superhero named 'Super Goof', which led to a popular series of spin-off comics. Another notable alternate comic version of Goofy was drawn by Adolfo Urtiága of the Jaime Diaz Studios who, between 1976 and 1987, made several full-length humorous 'Goofy' comic books, in which the dingo plays famous historical characters or adapts literary classics. When the American market for Disney comics dried out during the 1970s and 1980s, licensees from Brazil, Denmark, Italy, France and The Netherlands picked up the story production, which has also included many appearances of Goofy. In the Dutch Disney weekly Donald Duck, Goofy has his own educational feature inspired by the instruction films, 'Goofy Geeft Les' (1999- ), created by Jos Beekman and Michel Nadorp. Inspired by the same shorts, the French Le Journal de Mickey has run several 'Sport Goofy' pages, featuring Goofy as a sportsman.

Non-Disney animation career

In 1937, Pinto Colvig replaced Gus Wickie as the voice of Popeye's nemesis Bluto at the Fleischer Brothers Studio. He also voiced Gabby the town crier in 'Gulliver's Travels' (1939) and Mr. Creeper in 'Mr. Bug Goes to Town' (1941), the Fleischers' only attempts at feature-length animated films. Gabby was later featured in several short Fleischer cartoons until the studio went bankrupt in 1941. For Warner Brothers' Animation Studio, Colvig also provided some minor voices, the most notable being Cecil Crow in Bob Clampett's 'Aloha Hooey' (1942), Conrad the Cat in Chuck Jones' 'Conrad the Sailor' (1942) and Claude Hopper the kangaroo in Norm McCabe's 'Hop and Go' (1943).

Colvig's talent for mimicking animal sounds secured Colvig a job in Tex Avery's live-action serial 'Speaking of Animals' (1941-1946), where footage of real-life animals was combined with funny voice-overs. In a case of self-parody, Colvig voiced the brick-building pig in Tex Avery's war-time propaganda cartoon 'The Blitz Wolf' (1942) at MGM, a parody of Disney's 'The Three Little Pigs' in which he previously played the same character. He also voiced the stupid dog Meathead in Avery's Screwy Squirrel cartoon 'The Screwy Truant' (1945). For the latter short, he also provided Screwy's obnoxious laugh. In other 'Screwy Squirrel' cartoons, Meathead was voiced by Avery himself, while Screwy was played by Wally Maher. Colvig voiced the cat in Avery's 'King-Size Canary' (1947) and used Goofy's voice for the Country Wolf in Avery's 'Little Rural Riding Hood' (1949). Also at MGM's cartoon studio, he scripted Hanna-Barbera's 'Tom & Jerry' cartoon 'Quiet Please!' (1945), where Tom has to prevent Jerry from waking up the angry bulldog Spike. In Walter Lantz' 'Woody Woodpecker' series, Colvig played the sheriff, Wild Bill Hiccup and the Devil in the short 'Wild and Woody!' (1948).

Later film, radio and music career

Further in his career, Colvig remained active in Hollywood. He and fellow Disney voice actor Billy Bletcher dubbed the Lollipop Guild in Victor Fleming's classic film 'The Wizard of Oz' (1939). Colvig also voiced Coily the animated spring in the documentary short 'A Case of Spring Fever' (1940), produced for the car company Chevrolet. In this educational film, Coily the animated spring makes all the springs in the world disappear, after a human protagonist foolishly expresses his annoyance over these objects and wishes they "didn't exist". Soon enough, his wish is granted and drives him into despair, until he learns a valuable moral about the importance of springs in everyday use. Five decades later, this laughably corny short found a new audience when it was mocked in a 1999 episode of the TV show 'Mystery Science Theater 3000'.

Colvig made regular radio appearances, including on 'Amos 'n' Andy' and as Maxwell the car and Leona the horse in 'The Jack Benny Program'. In 1948, Colvig also recorded the novelty song 'Filbert the Frog'. The lyrics described a frog who enjoys singing and makes comical guttural sounds. Contrary to what many listeners assume, Colvig didn't provide the "glug" throat sounds. That part of the recording was done by performer Mickey Katz. A similar novelty song by Colvig was 'The Laughing Hyena Song' (1949).

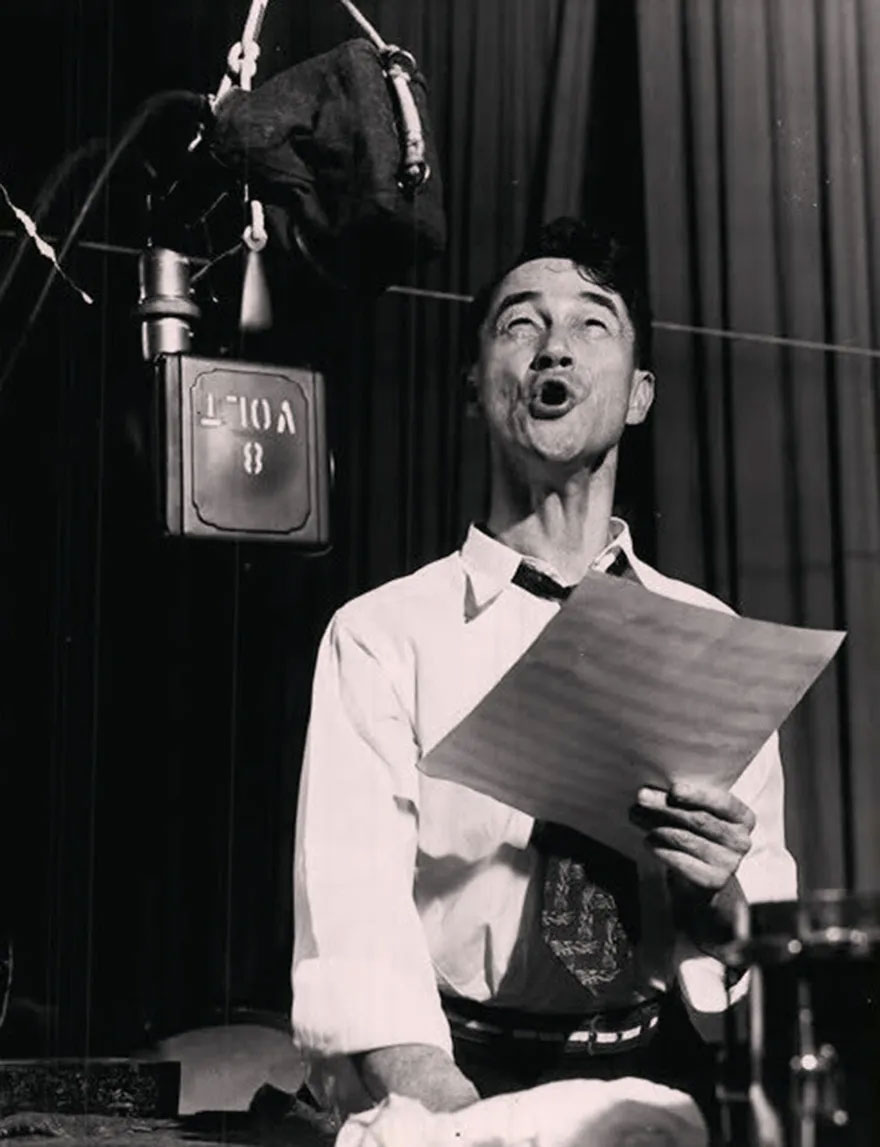

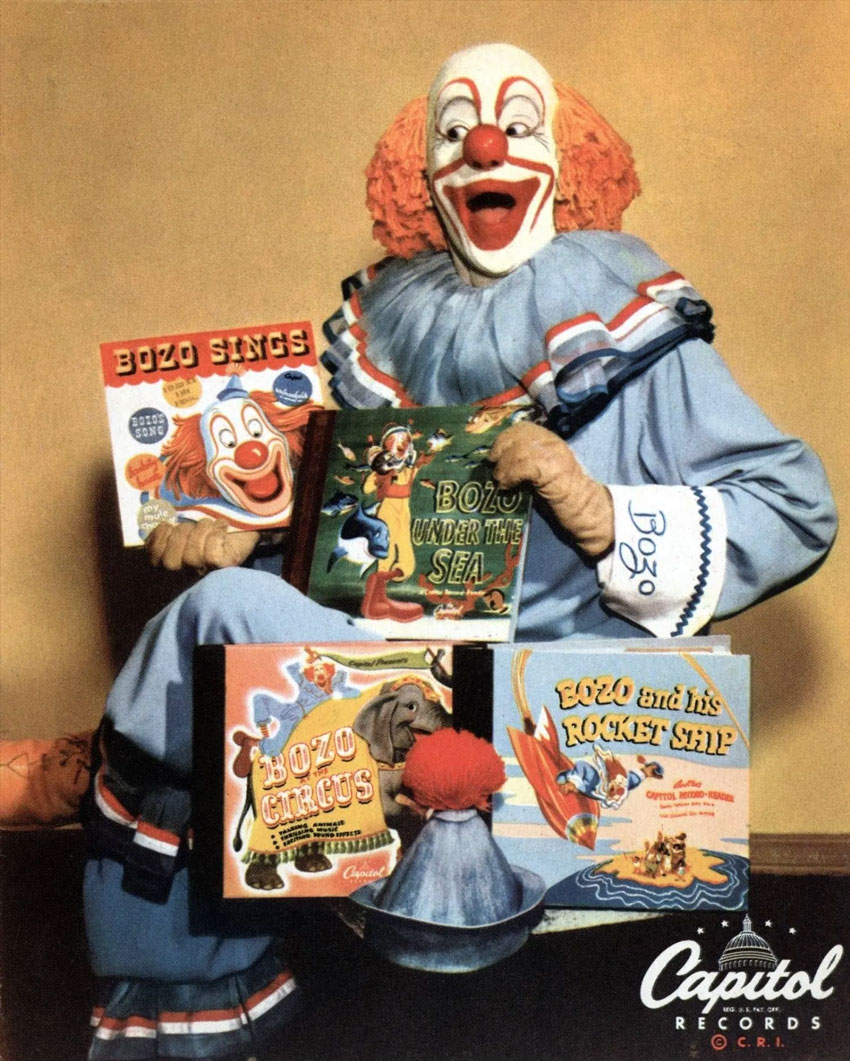

Pinto Colvig as Bozo the Clown.

Bozo the Clown

In 1946, U.S. businessman Alan W. Livingston recorded a children's audio play, narrated by a clown named Bozo. The record, produced by Capitol Records, came with a picture book, so young listeners could read along. Colvig did the voice of Bozo and up to eight other side characters. The record became a surprising bestseller, paving the way for more 'Bozo the Clown' merchandising. Some of the audio play records were illustrated by Cecil Beard and Norm McCabe. In July 1950, Dell Comics published a 'Bozo the Clown' comic book, as part of their Four Color Comics series (issue #295). In July 1951, he received his own quarterly comic book series, lasting until 1954. A second series was published by Dell between 1962 and 1963. The stories were scripted by Don Sheppard and drawn by artists like Carl Buettner and Lee Hooper. In Europe, Giacinto Gaudenzi of the Staff di If studio drew 'Bozo' stories for the French-Italian market.

Colvig also performed Bozo on stage. From 1949 on, he had his own successful TV show, 'Bozo's Circus', broadcast on KTTV-Channel 11 (CBS). He performed the long-haired clown regularly until 1956. Since so many commercial offers came in, he couldn't do all of it alone, so different actors were hired to play Bozo. Many local TV shows, for instance, were licensed to use his physical likeness and otherwise create their own content. When Colvig retired from the role, it was therefore easy to find a replacement and continue the 'Bozo the Clown' franchise for decades. In 1959, for instance, Colvig's son, Vance Colvig Jr. (1918-1991), played the role. Decades later, Bozo the Clown is still the most famous real-life TV clown of all time, even though the last 'Bozo' show went off the air on 14 July 2001.

Death and legacy

Pinto Colvig was a lifelong smoker, which contributed to his health problems. Remarkably enough, when the detrimental effects of smoking became clear in 1963-1964, Colvig was one of the first celebrities to support anti-smoking campaigns. He was in favor of a government bill to put warning labels on cigarette packages, an idea that only later became a global practice. In 1967, Pinto Colvig died in Woodland Hills, Los Angeles, from lung cancer. He was 75. His personal archives were donated to the Southern Oregon Historical Society in 1978. In 1993, Colvig was posthumously named a Disney Legend. On 23 May 2004 he was also inducted in the International Clown Hall of Fame in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Self-portrait.