'Seaman Si' (4 November 1918).

Perce Pearce was an American film scriptwriter, producer and director who worked for the Walt Disney Company from 1935 until 1953. He is best remembered as the scriptwriter of the 'Sorcerer's Apprentice' segment in 'Fantasia' (1940) and as story director of 'Bambi' (1942). Earlier in his career, Pearce drew the newspaper gag comic series 'Seaman Si' (1916-1918) and served as ghost artist on 'The Captain and the Kids' for Rudolph Dirks.

Early life

Percival C. Pearce was born in 1899 in Waukegan, Illinois. He was the son of a physician of British descent. In 1919, a year after his graduation from high school, he moved to Denver, Colorado and later studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Chicago.

Seaman Si

Perce Pearce did his first cartooning while still a high school student, working for The Chicago Herald and the Publicity Feature Bureau. At age sixteen, he developed the comic feature 'Seaman Si' (1916-1918) for The Great Lakes Bulletin, a military newspaper circulating in Great Lakes, Illinois and distributed at the U.S. Naval Training Center. The main star is a chubby, well-meaning but fairly stupid and accident-prone sailor. The so-called "funniest "Gob" in the Navy" also saw print in a 1916 self-published landscape-format compilation book, reprinted in 1918 by Reilly & Britton Co.

Cover for the 1916 'Seaman Si' compilation book.

Pearce additionally sold political caricatures and editorial cartoons to The New York Evening Post and, from late 1919 on, presumably also to The Denver Post. According to the book 'Walt's People - Talking with the Artists who Knew Him, Volume 12' (2012) by Didier Ghez and George Grant, Perce Pearce shared a room with fellow cartoonists John Campbell Cory and Charles Cahn. Pearce presumably continued drawing cartoons throughout the 1920s, but there is little information available about this period, except that he was a ghost artist on 'The Captain and The Kids' by Rudolph Dirks. By 1930, Pearce had moved to Bay City, Michigan, where according to the federal census, he ran his own company.

Disney

On 18 February 1935, Pearce went into animation, working for the Walt Disney Studios. He started as an inbetweener, but quickly moved up the ladder. In the previously mentioned Ghez and Grant book, Pearce is described as a talented self-promoter. He befriended one of his superiors, George Drake, by letting him win during bridge games. Pearce could articulate ideas in a calm, well-spoken and entertaining manner. Animation legend Shamus Culhane recalled that Pearce had a slurry voice reminiscent of Hollywood comedian W.C. Fields, but was still able to make everybody hang on to every word. He was a pipe smoker who often lit a match while talking. As he held the burning match in his hand, the fire slowly burned down to his fingers. But before he could actually hurt himself, he calmly lit his pipe and continued as if nothing was going on. This trick made audiences pay attention to him, helping Pearce move to Disney's story department, where his narrative talents were more useful. Whenever colleagues were too nervous to present their new material in a story meeting, he would fill in for them. Disney animator Wilfred Jackson recalled that Pearce often talked very quietly, so that his supervisors, including Walt Disney, listened with more attention and even moved closer to him to be able to hear him. Soon even "Uncle Walt" himself was impressed with Pearce.

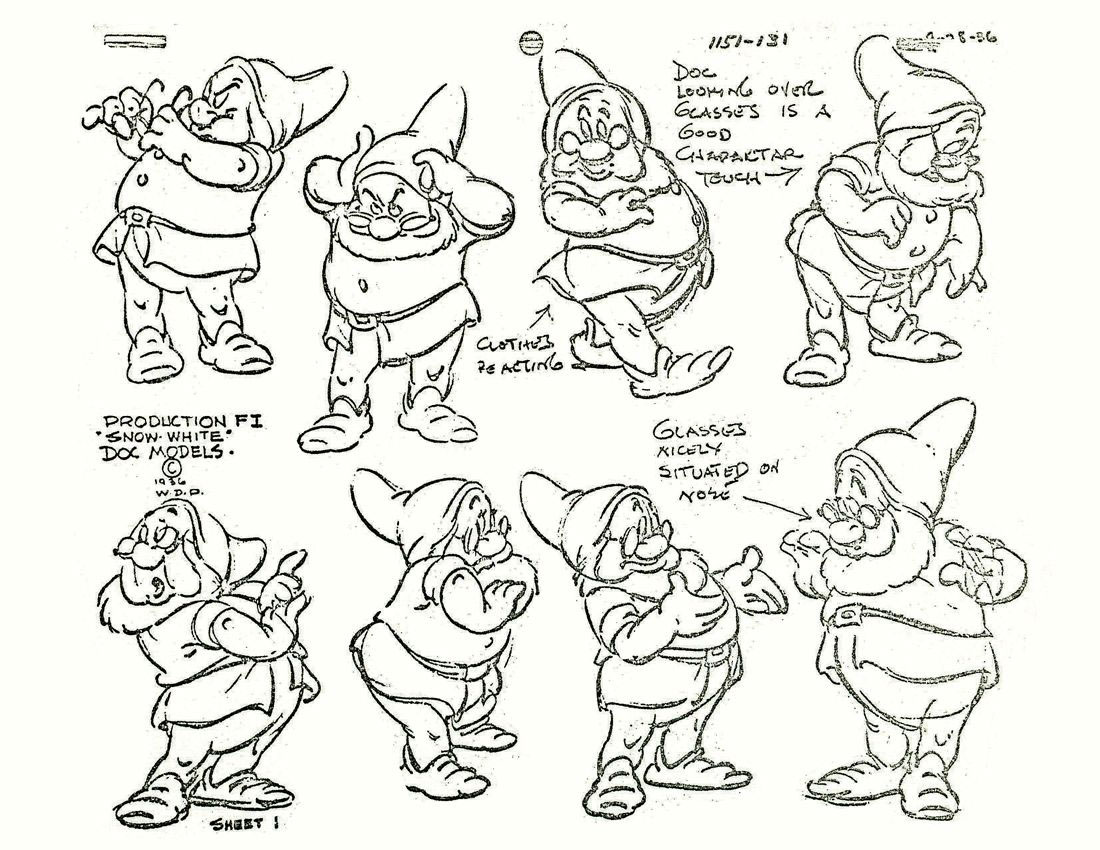

Modelsheet of "Doc", whose mannerisms were modeled after Perce Pearce. © Disney.

Snow White

Pearce's big break came when he was promoted to writer and co-director of Walt Disney's first animated feature 'Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs'. Walt Disney had the ambitious plan to adapt this well known fairy tale into an animated film with the same length as a live-action feature. A risky undertaking, since the company had never tried such a project before. Pearce, however, won Disney's trust and was instrumental in directing several key scenes. He is credited with the moment where Snow White and the Prince first meet. Pearce was also largely responsible for the frightening scene where Snow White runs through the dark forest while seeing monsters lurking behind every tree and branch. At the time, many viewers were genuinely scared. Steven Spielberg recalled that when he was a child, the scene made him run out of the theater, screaming. However, Pearce's greatest accomplishment was the characterization of the Seven Dwarfs. In the original fairy tale, they are just a generic group of characters. Disney decided to give them all a distinctive and specific personality. During story meetings, Pearce was very good at acting out their mannerisms. The animators used his performances as a guideline. Particularly Doc, the leader, was entirely based on Pearce.

Pearce's work paid off. When 'Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs' premiered in late 1937, it became a surprise global box office hit. Many viewers agreed that the Dwarfs were the highlight of the film. This solidified Pearce's role in the next decades as one of Disney's most important screenwriters.

Fantasia

After the success of 'Snow White', Walt Disney immediately began production on two new animated features. One was based on Carlo Collodi's children's book 'Pinocchio', the other a more experimental film that provided stories set to famous pieces of classical music: 'Fantasia'. Pearce worked on the latter picture, more specifically the 'Sorcerer's Apprentice' segment. Based on Paul Dukas' musical adaptation of Goethe's narrative poem, it tells the story of a wizard's assistant. Fed up with mopping the floor, he enchants a broom, so the thing can do the work for him. However, since he can't get the broom to stop, the place is soon flooded with water. Just in the nick of time, the wizard returns and breaks the spell. Originally, Disney intended 'The Sorcerer's Apprentice' as an animated short, but given the length, it was eventually integrated into 'Fantasia'. Since there was already a story to go with the music, Pearce had little trouble with writing the narrative. The tricky part was thinking up how the action would match the music.

Pearce's assignment to 'The Sorcerer's Apprentice' might be explained from the fact that Disney originally wanted to use Dopey the dwarf from 'Snow White' in the role of the Apprentice. Pearce understood the Dwarfs' personalities better than anybody, and Dopey was a silent character who would fit well in a cartoon with only music on the soundtrack. But in the end, Disney replaced Dopey with Mickey Mouse. At the time, Mickey's popularity was declining in favor of Donald Duck, so Disney wanted to bring his superstar back into the spotlight.

Upon their release, both 'Pinocchio' (1940) and 'Fantasia' (1940) lost money at the box office, since World War II had cut off the European market. On top of that, 'Fantasia' divided audiences who considered the film either too pretentious or too kitschy. The one segment spared from criticism was 'The Sorcerer's Apprentice', where the story and music matched perfectly. By the 1960s, 'Fantasia' was revalued as a unique and artistic film. When the 2000 sequel came out, 'Fantasia 2000', the 'Sorcerer's Apprentice' was the only segment included from the original film without alterations.

Still from 'Fantasia' (1940). © Disney.

Bambi

After 'Pinocchio' and 'Fantasia' didn't do well at the box office, Walt Disney was lucky that 'Dumbo' (1941) became a surprise hit. His next feature, 'Bambi' (1942), was based on Felix Salten's book of the same name, and told the story of a young deer growing up in harsh nature. Pearce and Larry Morey were appointed as scriptwriters. Uncharacteristically, Walt Disney gave Pearce remarkable autonomy. He developed the story into a beautiful and moving feature film. The scene where Bambi's mother is shot has moved generations of children to tears and turned millions of people against game hunting. Disney himself was said to be genuinely satisfied with the end result. But during the war years, audiences were not in the mood for stories about happy forest animals, while people were dying in combat every day. 'Bambi' only became a classic after the war. Besides scriptwriting, Pearce also voiced the mole who says "Nice sunny day!" to Bambi.

Other World War II projects

During World War II, Pearce also worked on some less iconic film projects. He was a co-director on the military propaganda film 'Victory Through Air Power' (1942), produced by Walt Disney to promote strategic bombing. Both U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt and U.K. Prime Minister Winston Churchill praised the film as a perfect way to advocate this strategy among general audiences. Pearce was also involved in the Disney adaptation of Kenneth Grahame's 'The Wind in the Willows', which wasn't released until after the war as part of the anthology film 'The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad' (1949). Pearce additionally spent a lot of time directing an adaptation of Roald Dahl's children's story 'The Gremlins', about little monsters that sabotage airplanes. A book version was released in 1943, illustrated by Disney animators Bill Justice and Al Dempster, but the film itself stalled out in the development phase. Dahl always claimed the gremlins were his own invention, but stories about these creatures already circulated decades earlier. Disney was therefore not sure if the characters weren't copyrighted by anyone else, especially when Warner Bros released the Bugs Bunny cartoon 'Falling Hare' (1943) - directed by Bob Clampett - in which Bugs travels by plane and is outwitted by a gremlin. A year later, Clampett directed another gremlin-themed cartoon, 'Russian Rhapsody' (1944), in which the creatures lampoon Adolf Hitler. The Disney version of the Gremlins did appear in a couple of 1943 comic book stories, drawn by Vivie Risto and Walt Kelly.

Live-action films

After World War II, Walt Disney was less interested in animation and focused on live-action family films. At this point, his trust in Pearce was so strong that he was appointed assistant-producer and second-unit director on the films 'Song Of The South' (1946) and 'So Dear To My Heart' (1948). Both combined live-action with animated segments. In 1946 Disney, screenwriter John Tucker Battle and Pearce traveled to England to scout locations for the upcoming live-action film 'Darby O' Gill and The Little People', which was actually set In Ireland. The film, based on the stories by Herminie Templeton Kavanagh, premiered in 1959, four years after Pearce's death. In 1949, Perce Pearce and production manager Fred Leahy traveled to the British Isles to supervise the live-action adaptation of Robert Louis Stevenson's classic pirate novel 'Treasure Island' (1950). Robert Crumb and his brother Charles Crumb had fond childhood memories of watching Disney's 'Treasure Island'.

Pearce was also producer of 'The Story of Robin Hood and His Merrie Men' (1952), 'The Sword and the Rose' (1953) and 'Rob Roy, the Highland Rogue' (1953), all live-action costume films in a historical British setting. While all these films enjoyed a decent box office run, they didn't turn out to be the hits Disney was hoping for. According to animator Dick Huemer, Disney blamed Pearce for their lack of financial success and the two men drifted more apart.

Final years and death

After filming several Disney live-action films in England, Pearce decided to stay in the country, because the Bank of England claimed that his British bank accounts couldn't be transferred to the USA. He bought a cottage in the English countryside, where he spent the rest of his life. Officially, he left the Disney company on 2 October 1953, but in reality he remained involved with the company until his death. Perce Pearce, Bill Walsh and Hal Adelquist were executive scriptwriters on the Disney TV show 'The Mickey Mouse Club' (1955), although Pearce never lived to see the premiere of this popular children's show. One week earlier, on 4 July 1955, Perce Pearce suddenly died behind his desk from a coronary thrombosis. He was 56 years old.

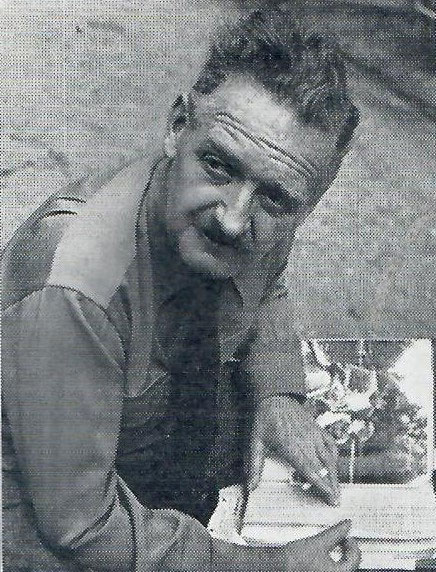

Perce Pearce in August 1949.