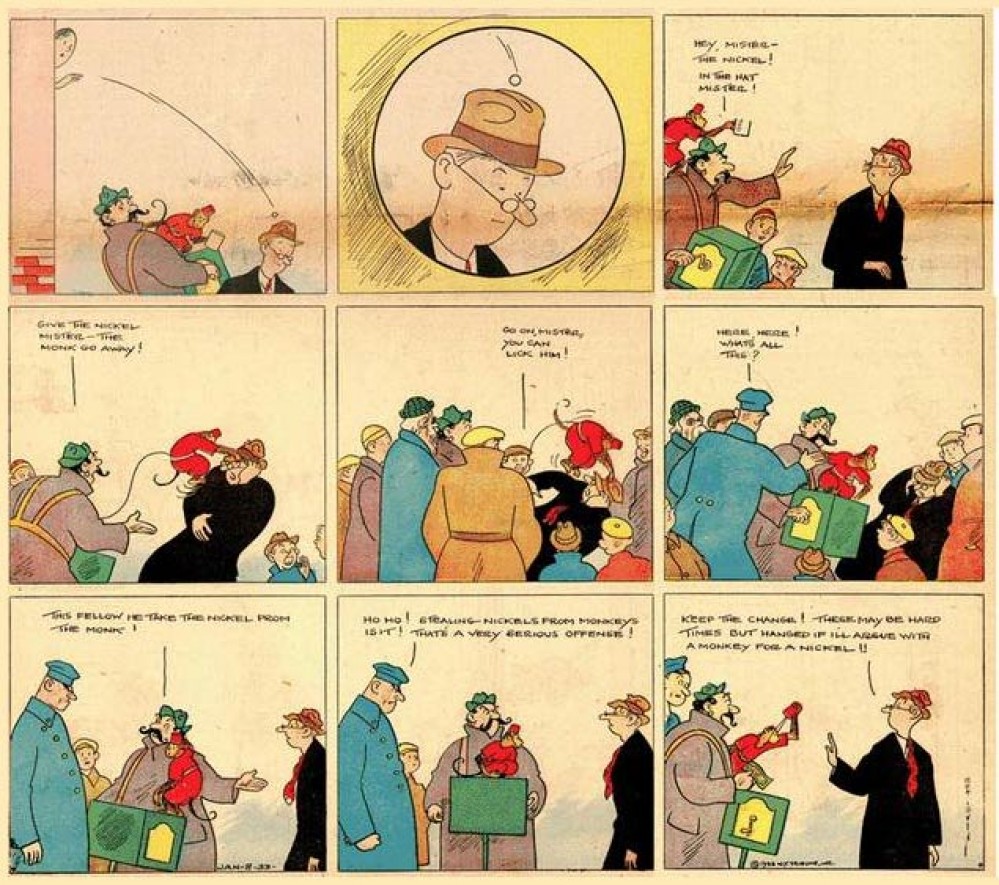

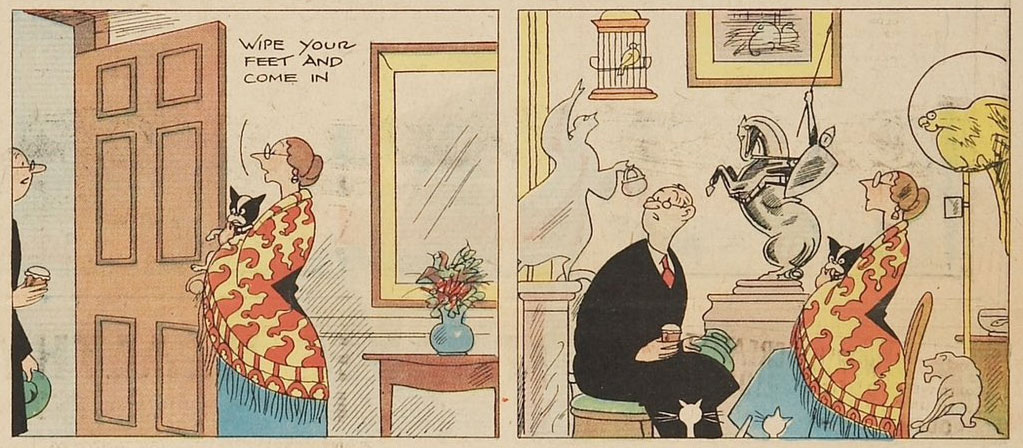

'The Smythes'.

Rea Irvin was an American graphic artist, best known as a co-founder and frequent contributor to the influential magazine The New Yorker. Besides drawing various illustrations and cartoons, he was their first art editor and designed The New Yorker's mascot Eustace Tilley. While best known for his stylish and elegant one-panel cartoons, Irvin also drew a few rare comic features in his career, including his best known series 'The Smythes' (1930-1936).

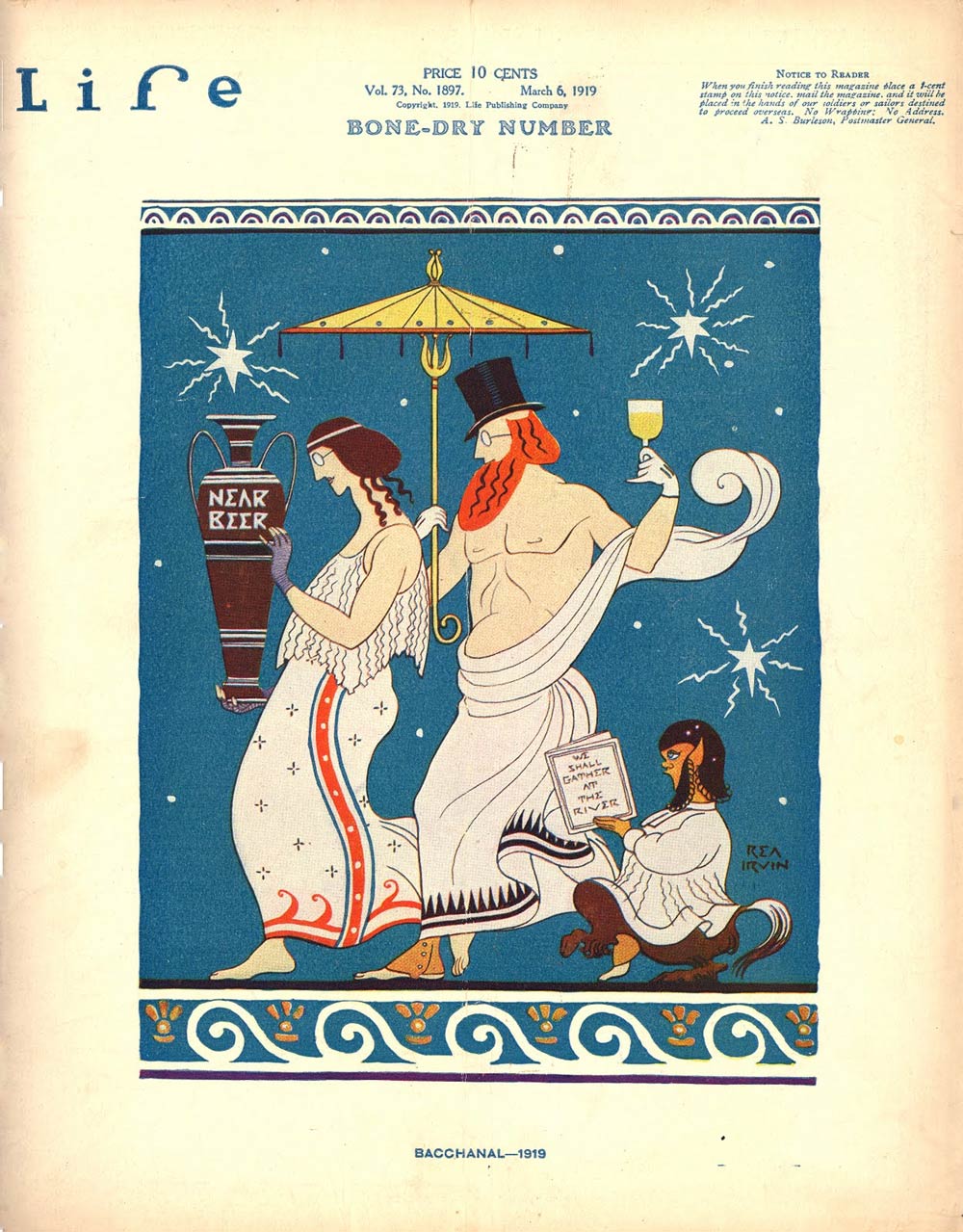

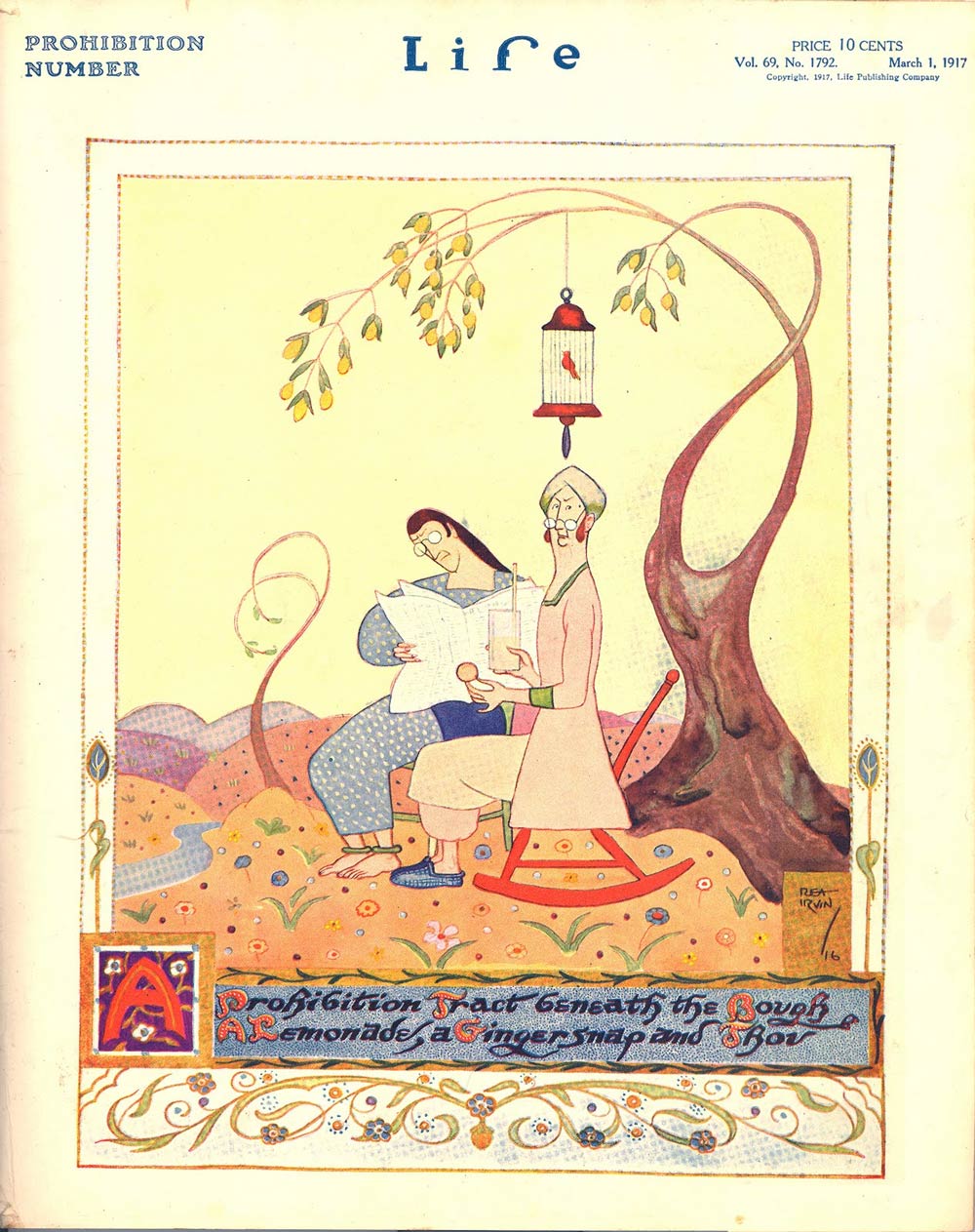

Cover illustrations for Life Magazine, respectively issue #1897 (6 March 1919) and issue #1792 (1 March 1917).

Early life and career

Rea Irvin was born in 1881 in San Francisco, California. He studied at the Mark Hopkins Art Institute, but dropped out after six months. At the turn of the 19th into the 20th century, he published his first cartoons in the San Francisco Examiner and the San Francisco Evening Post. To earn a living, he also worked as theatrical and film actor, as well as a pianist. He was a member of the Players, a private theatrical and literary club at Gramercy Park. During the First World War, he served in the U.S. Army.

Much of his early work was published in Red Book, Green Book, Cosmopolitan, the Honolulu Advertiser and the humorous weekly magazine Life, for which he worked as an art editor until he was fired in 1924. Among his early work were also short-lived weekday comic/cartoon features like 'Isn't He The Sly Dog?' (American-Journal-Examiner, 20 August-21 September 1908), 'How Romantic Is' (NEA Syndicate, 24 September-3 October 1907) and 'Even So' (Joseph Pulitzer's The New York World, 6 through 21 October 1908). Throughout his career, Irvin was additionally active as an advertising artist and created illustrations for Murad cigarettes, the Tennis Club and the Country Club.

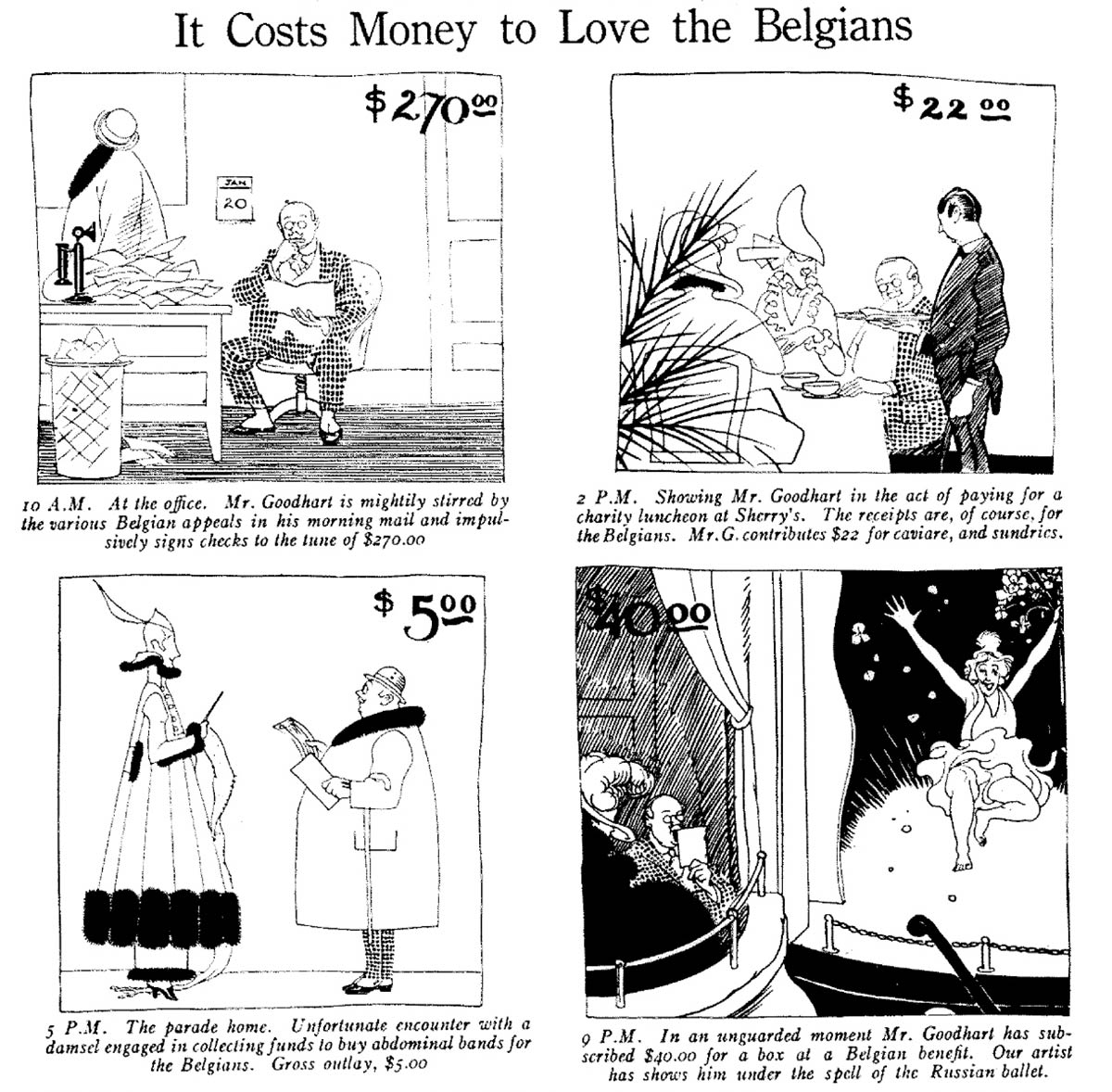

'It Costs Money to Love the Belgians', Vanity Fair, February 1915.

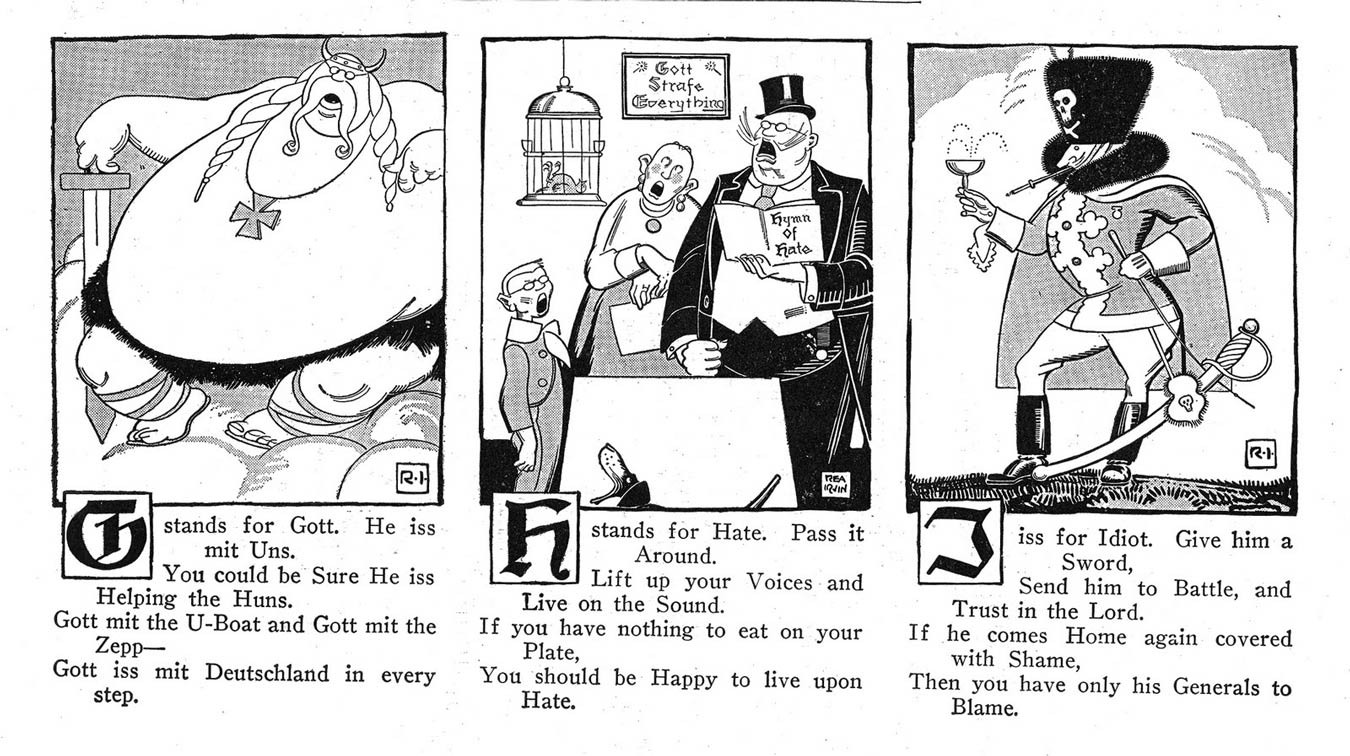

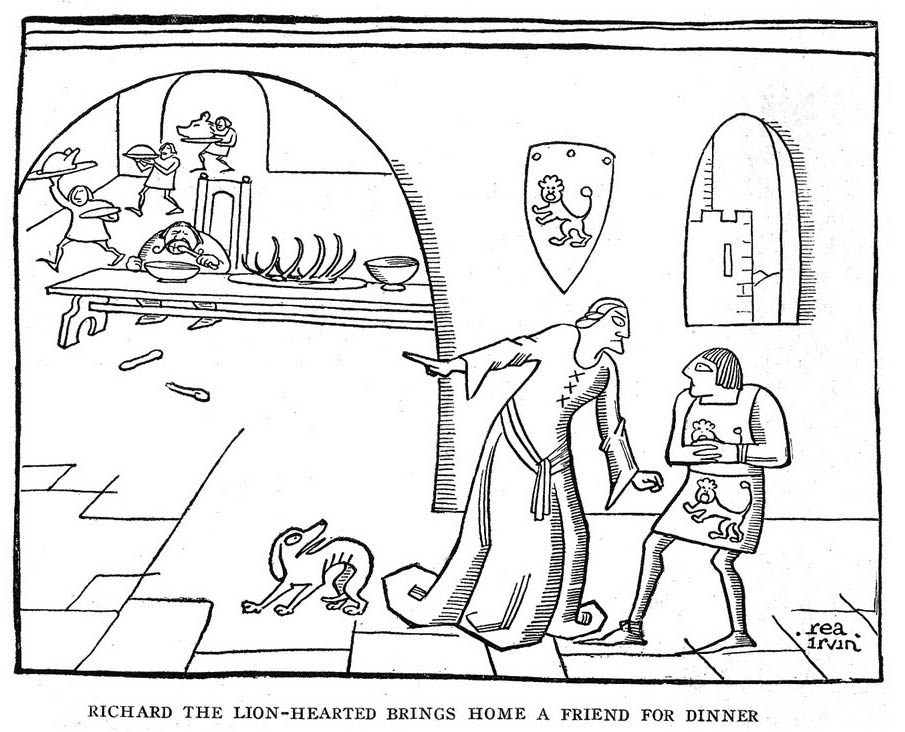

Early text comics

In February 1915, Irvin drew a text comic for Vanity Fair, named 'It Costs Money to Love the Belgians' (1915). It features a man named Mr. Goodhart who has to reach deep into his pockets wherever he goes to buy war bonds to support Belgium during the First World War. The work is notable for motivating readers to donate money to Belgian war victims and their struggling army at a time when the United States still held a neutral stance. In 1917, the USA entered World War I after all. On 29 November of that year, Irvin drew a text comic which ridiculed the Germany army in the form of an alphabetic rhyme. In May 1920, Irvin drew another text comic, 'Wives of Famous Men', which depicted moments in Western history when historical characters had trouble with their spouses. The artwork was made to resemble an ancient woodcut.

Text comic for Vanity Fair, 29 November 1917.

Style and personality

Irvin was a bit of an eccentric man. He regularly wore a fedora hat with a very wide brim. His home in Newton, Connecticut, had numerous animals, including some horses which he called his "models". The artist worked in a very round and elegant style, inspired by the then-fashionable Art Deco movement and his love for Chinese and Japanese scroll paintings. It gave his work a sophisticated look, which suited the various prestigious magazines he made his illustrations for.

'Wives of Famous Men', Vanity Fair, May 1920.

The New Yorker

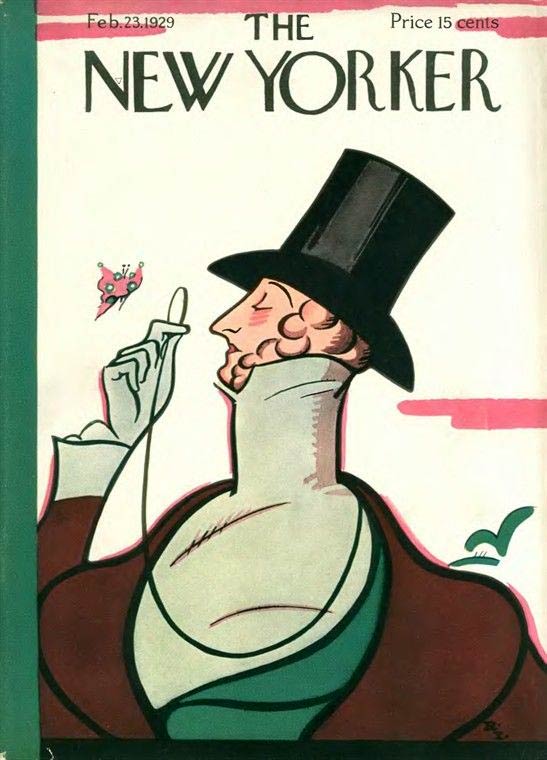

No magazine fit Irvin's graphic style better than The New Yorker, in which he was present from its very first issue of 21 February 1925. The magazine was created by the journalist Harold Ross and his wife Jane Grant, with the goal of establishing a humor magazine offering room for various amusing short stories, columns and particularly cartoons. The pair wanted to promote a classy public image. For the first cover, the editors wanted to show theater curtains being pulled away, revealing the Manhattan skyline. At the last minute, Rea Irvin came up with a more eye-catching idea. He drew a dandy in a high hat, inspired by a 1834 caricature by James Fraser, depicting Count d'Orsay. The dandy sports a monocle and observes a butterfly through it. Columnist Corey Ford named the character Eustace Tilley, inspired by the last name of one of his aunts. The cover had the desired effect. The first issue reached the right demographic and established The New Yorker's reputation for quality reading.

Cover illustration for the first issue of The New Yorker, 21 February 1925, marking the debut of their mascot Eustace Tilley.

Soon, The New Yorker became one of the best-selling American magazines in the world. Many other newspapers and magazines across the globe that tried to maintain a similar sophisticated public image all took their inspiration from it. Rea Irin's Eustace Tilley character was featured as often as possible. He not only appeared on several covers, but traditionally also headed the magazine's 'Talk of the Town' column. In that capacity, he is arguably one of the most recognizable magazine mascots in the world, along with the Playboy Bunny (Hugh Hefner's Playboy) and Alfred E. Neuman (Mad Magazine, designed by Norman Mingo).

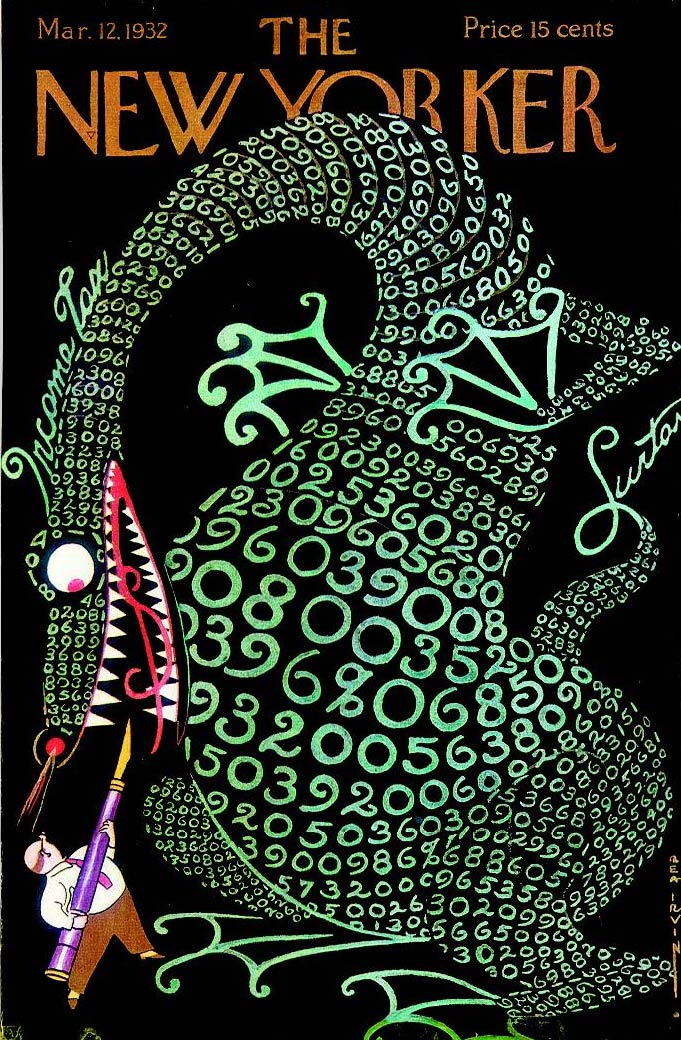

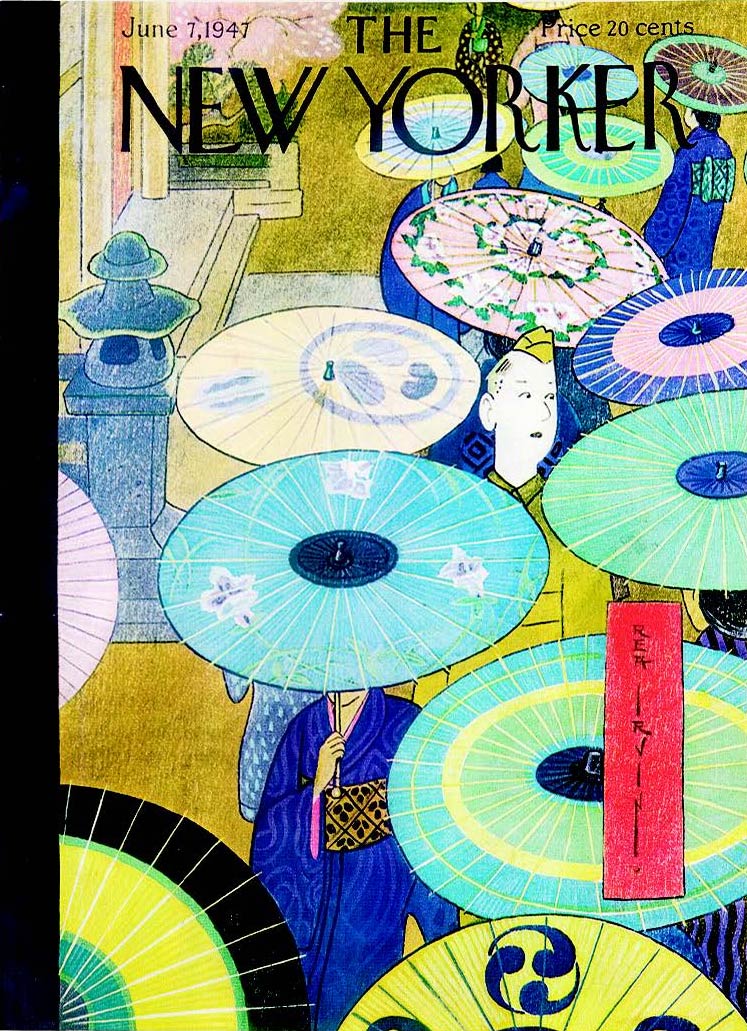

Cover illustrations for The New Yorker, respectively 12 March 1932 and 7 June 1947.

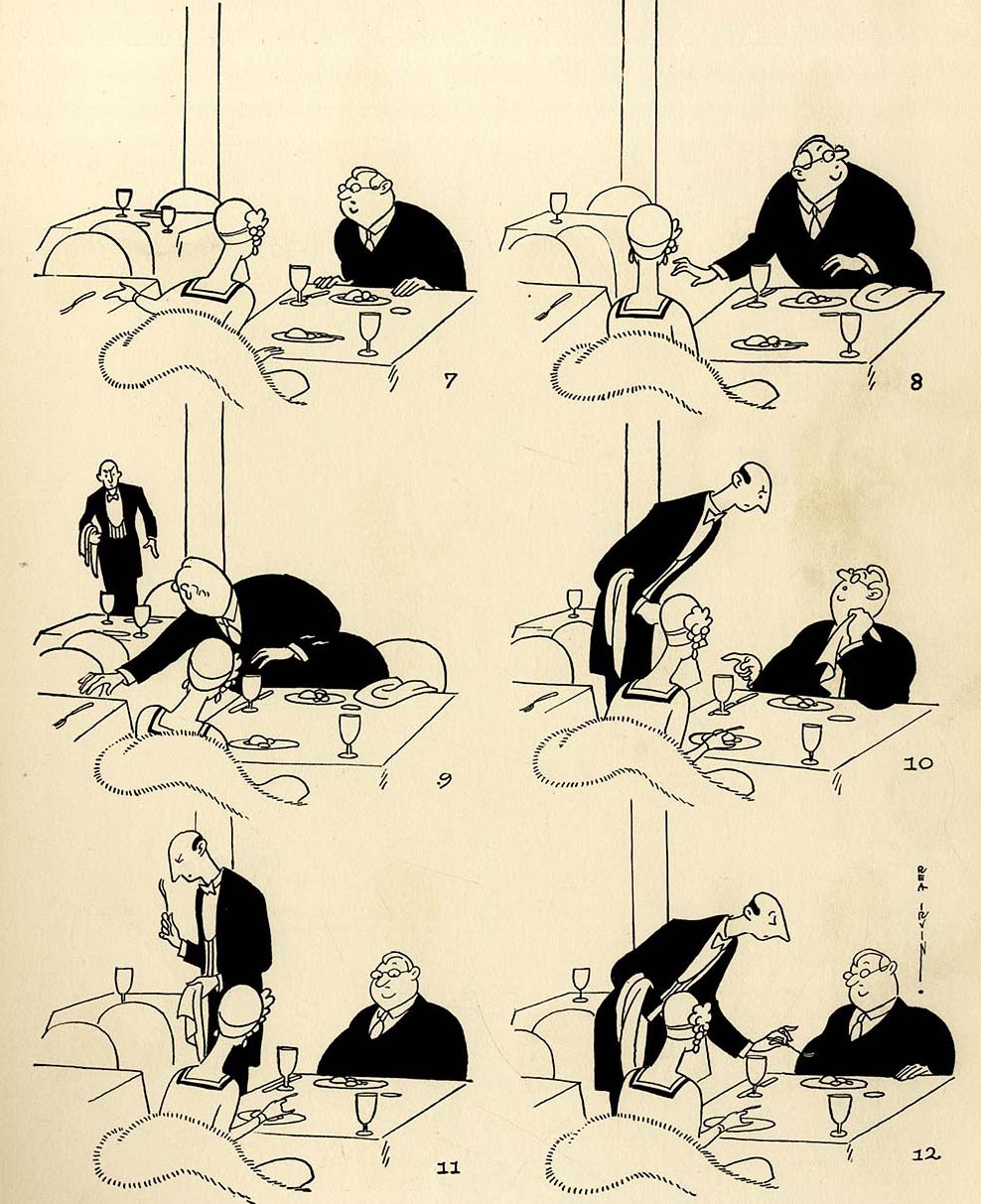

As an uncredited art editor, Irvin was closely involved with every issue of The New Yorker. He designed their display typeface, inspired by the lettering of Allen Lewis, which has since then been named the "Irvin type". He kept a close eye on the cartoons featured in the magazine's pages. Much like chief editor Harold Ross, he was a notorious control freak. He once scorned a cartoonist for not drawing "better dust" on a cover of a Ford Model T standing on a dusty back road. Another time he made technical personnel check a drawing of a PT boat, because he feared the torpedo tubes didn't look realistic enough. And when he noticed too many cartoons had featured characters counting sheep, he asked the editors to cut them down a bit. Irvin also created various illustrations, caricatures and cartoons of his own. One of his best-known was 'The Young Man Who Asked for a Pack of Camels in Dunhills', which shows a man in a tobacco store ignored by the store owner. Most of his cartoons were either one-panel illustrations with humorous captions, or pantomime comics with the gentle punchline found in the humorous details.

'The Smythes' (5 November 1933).

The Smythes

Between 15 June 1930 and 25 October 1936, Rea Irvin created the newspaper Sunday gag comic strip 'The Smythes', which ran in The New York Herald Tribune. Featuring mostly gentle humor, the gags centered around a middle class suburban family, consisting of father John, mother Margie, and their two children, Willie and Maudie. Despite the Great Depression, the family is eager to climb the social ladder, and Irvin gracefully shows them navigate ill-fated dinner parties with pompous socialites, fend off robbers dressed as Santa, and get chased out of restaurants by cleaver-wielding chefs.

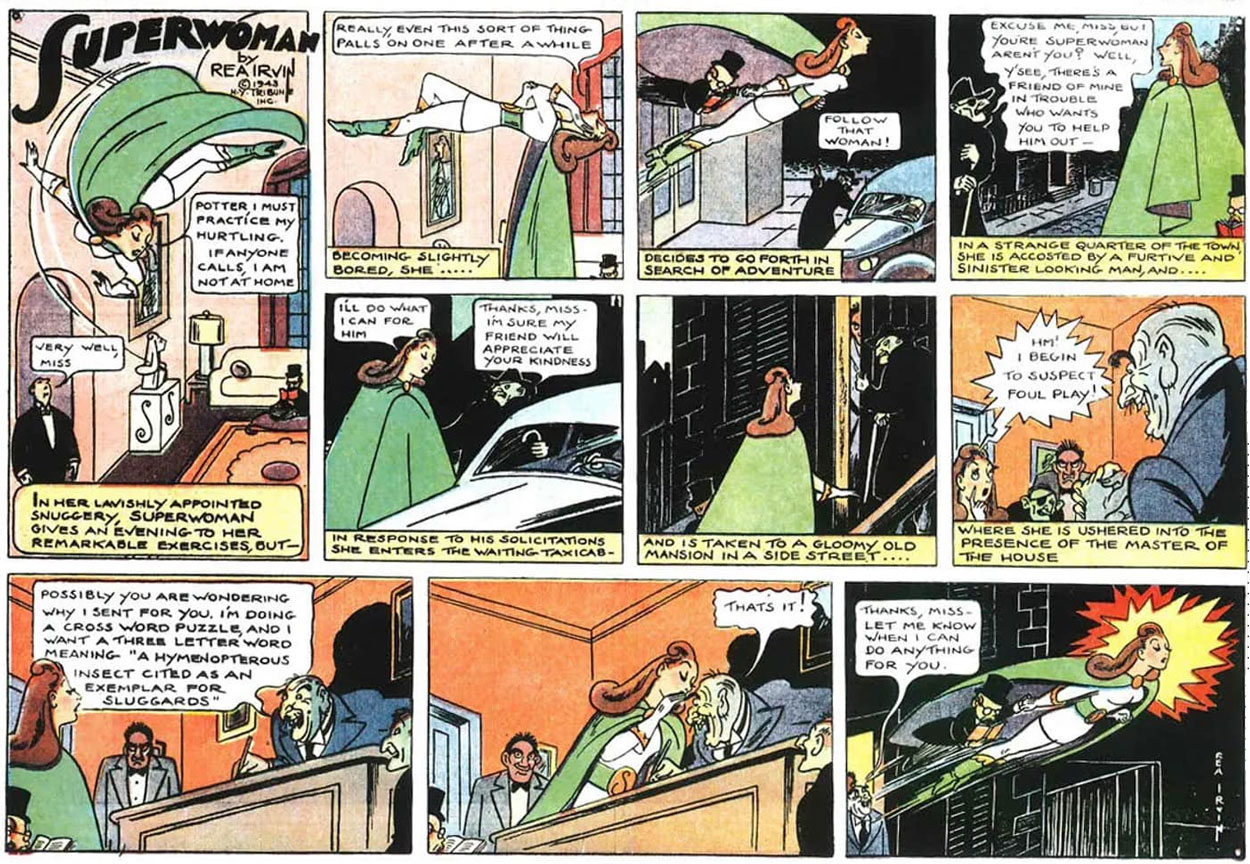

Superwoman

In 1943, Irvin created a superhero parody, titled 'Superwoman', presenting a female version of Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster's 'Superman'. It ran as a Sunday comic on 27 June 1943, serialized in The New York Herald Tribune and The Oakland Tribune, but was canceled after only one episode. Unbeknownst to Irvin, National Periodicals (DC) had already copyrighted the name 'Superwoman' and released a serious story about her, written by Jerry Siegel and drawn by George Roussos. They sent a cease-and-desist letter and Irvin was forced to drop his spoof.

The sole episode of Rea Irvin's 'Superwoman' (27 June 1943).

Final years, death and legacy

Irvin stayed with The New Yorker until 1951, when founder Harold Ross passed away. After his friend's death, Irvin's good relationship with the magazine started to diminish. Ross's successors were less interested in Irvin's cartoons and refused many of them. In 1972, the cartoonist passed away in Frederiksted, Saint Croix, at age 90 from a stroke. James Thurber credited Irvin with "doing more to develop the style and excellence of the New Yorker drawings and covers, than anyone else, and being the main and shining reason that the magazine's comic art in the first two years was far superior to its humorous prose."

Recognition

During his long career, Irvin didn't receive any awards. Yet in 2025, he was posthumously inducted into the Will Eisner Award Hall of Fame. In that same year, a book collection of Rea Irvin's 'The Smythes' was released by New York Review Comics, with an introduction by R. Kikuo Johnson and Dash Shaw, and an afterword by Caitlin McGurk.