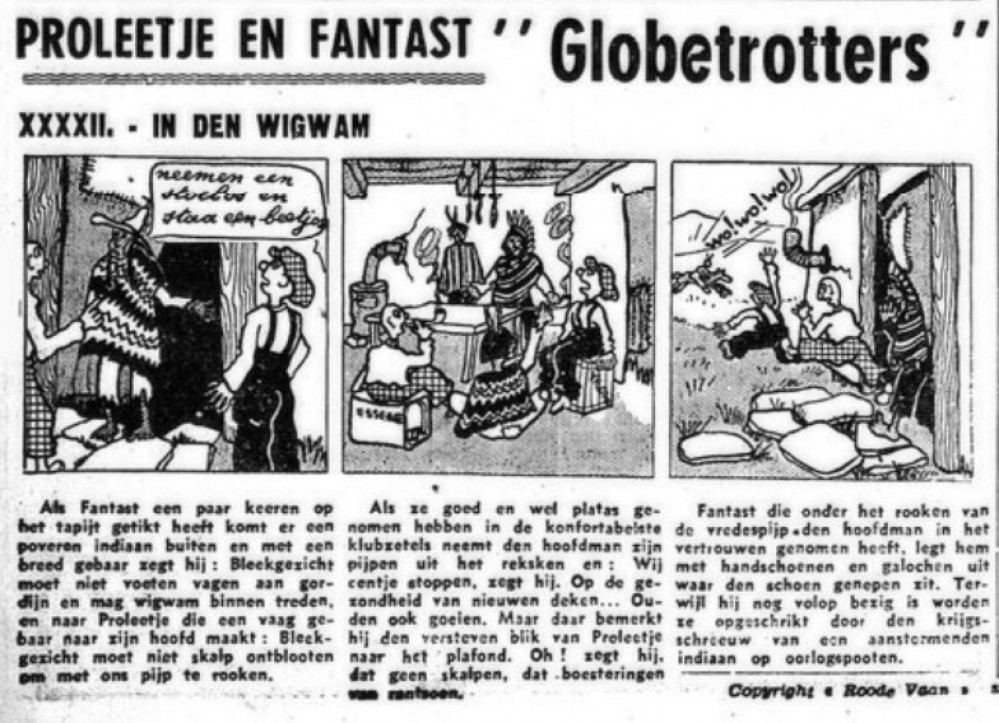

'Proleetje en Fantast', second story (De Rode Vaan, 7 January 1947).

Maurice Roggeman was a Belgian painter, illustrator and comic artist, best known as the illustrator and book cover designer for the acclaimed Belgian novelist Louis Paul Boon. Roggeman also drew a Communist propaganda adventure comic scripted by Boon, 'Proleetje & Fantast' (1946-1947), which appeared in the Communist paper De Rode Vaan.

Life and career

Maurice Roggeman was born in 1912 in Aalst, East Flanders, six months after the famous Belgian writer Louis Paul Boon. Also born in Aalst, Boon later gained fame with his novels 'De Kapellekensbaan' (1953), 'De Bende van Jan de Lichte' (1957), 'Priester Daens' (1971) and 'Mieke Maaike's Obscene Jeugd' (1972). His work is praised for its experimental nature, social consciousness and cheeky eroticism. Apart from writing, Boon was also active as a columnist and a painter. As students at the Academy of Fine Arts in Aalst during the 1930s, Boon and Roggeman first met, and became lifelong friends. During World War II, Roggeman made illegal prints in his studio in the De Marollen neighborhood in Brussels. He also designed the front covers for Boon's earliest novels: 'De Voorstad Groeit' (1943), 'Abel Gholaerts' (1944) and 'Vergeten Straat' (1946).

From 6 December 1945 until 20-21 July 1946, Boon serialized 17 humorous short stories about the character Jo in the Communist paper De Rode Vaan, which were all illustrated by Roggeman. Decades later, in 1989, they were collected in book form by De Arbeiderspers under the title 'Vertellingen van Jo'. Between 12 January and 6 March 1946, De Rode Vaan printed a column by Boon in which he described the strong divide between rich and poor in post-war Brussels. Again, Roggeman provided the illustrations. These columns were later collected in book form as 'Brussel, Een Oerwoud' ('t Gasthuys – Stedelijk Museum Aalst, 2020). Other artists who have livened up writings by Boon have been GoT ('Dorp in Vlaanderen', De Arbeiderspers, 1966) and Rony Heirman ('Mijn Oude Schoolmeester', 1972). In 1985, Edwin Nagels made a comic adaptation of Boon's 'De Bende van Jan de Lichte'.

Boon gave his friend Roggeman the affectionate nickname "Morris". Two characters in his literary oeuvre were based on Roggeman, namely Morriske in 'De Voorstad Groeit' and Tippetotje in 'De Kapellekensbaan'. Boon and Roggeman often corresponded through letters, which were later collected in the book 'Brieven aan Morris' (Gerards & Schreurs, Maastricht, 1989). Nevertheless, their friendship came to a sudden end in 1946 and wasn't restored until over four decades later. Roggeman gave two reasons for their fractured bond. First of all, Roggeman refused to have his daughter baptized. For Boon, who was an atheist, this was no big deal, but his pious wife Jeanneke saw this as blasphemy. The second reason for their friction was a heated discussion about a book by Boon, titled 'Drie Menschen Tussen Muren'. He had written it in 1941 and gave the sole lino-print copy to Roggeman. It seems that Roggeman either lost it for a while or refused to give it back. Either way, it took until 1969 before it was eventually returned to Boon and printed. In 1978, Roggeman contacted Boon again and the old friends enjoyed a pleasant reunion before Boon eventually died in 1979. Maurice Roggeman survived him for another 11 years, eventually passing away in 1990. He was the uncle of the poet and writer Willem M. Roggeman (b. 1935).

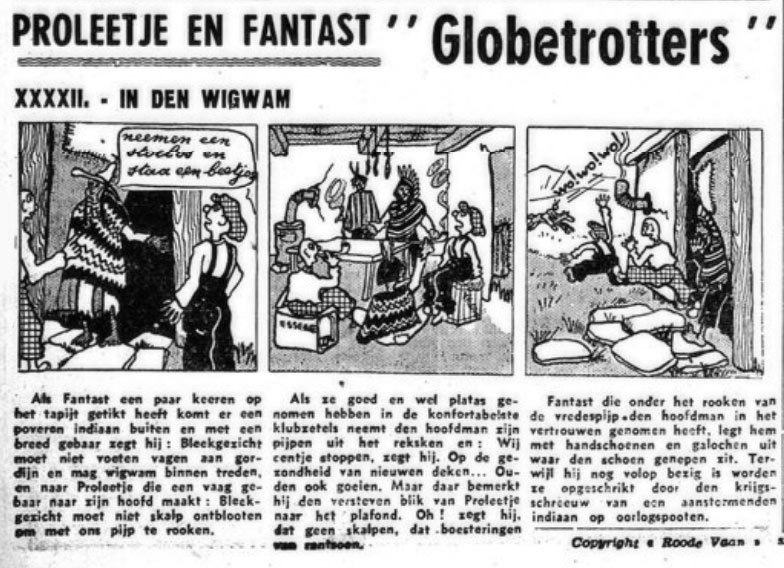

'De Wonderlijke Avonturen van Proleetje en Fantast' (De Rode Vaan, 17 July 1946).

Proleetje & Fantast

After World War II, Roggeman illustrated Louis Paul Boon's comic feature 'Proleetje en Fantast' (1 May 1946 - 20 January 1947), which ran in the Communist paper De Roode Vaan as requested by the editors. The name "Proleetje" was a pun on the word "proletarian". Compared with most other post-war comics published in Flanders, 'Proleetje en Fantast' didn't feature the typical Catholic, pro-Western and anti-Communist propaganda, but instead advocated propaganda for the opposite side, ridiculing capitalism, royalism and the United States. It was also not presented in the balloon comic format, but as a text comic with text underneath the images. Only a few panels make use of speech balloons.

In the first story, 'In Het Land van Koning Trust' (1 May - 28 September 1946), Proleetje and Fantast live in a kingdom ruled by an evil monarch named "Trust" (an obvious nod to a "business trust"). King Trust rules over a "thousand-year empire" and owns a personal slave named "Jef Buchenwald", respectively referencing Hitler's so-called "thousand year empire" and the Nazi camp Buchenwald. The tyrant exploits his people in his factories, protected by a powerful army. Proleetje and Fantast organize an uprising. Although it is never specified as a Communist revolt, the characters do refer to one another as "comrade" and the symbols of their rebellion are the hammer and sickle.

Originally, Boon and Roggeman wanted to create a satirical comic in the style of Marten Toonder's Dutch comic strip 'Tom Poes'. But 'Proleetje en Fantast' reads more like a straightforward Communist propaganda comic, with only a few humorous touches and references to then current events. It is known that Boon and Roggeman didn't receive much creative freedom in De Rode Vaan. Their script had to follow strict ideological guidelines. Because of this, some literary critics doubt how much input Boon really had in the story, if he had any at all. During the serialization of the first story, he suddenly fell ill, making it hard to reach his deadlines. By the time of the second story, 'Proleetje en Fantast, Globetrotters' (16 November 1946-20 January 1947), Roggeman scripted the entire narrative on his own. It has been suggested that Boon possibly feigned his illness, because he lost interest in the story, whereupon Roggeman possibly already ghost-wrote the plot during the first story. While Boon had sympathies for the Communist cause, he was very nihilistic about whether mankind could ever achieve a "socialist paradise". The ending of 'Proleetje and Fantast', in which the heroes succeed in their revolution, therefore feels very atypical of his style.

Roggeman didn't have fond memories of the 'Proleetje en Fantast' strip. Partially because his artwork had to be done after hours to combine it with his day job, but mostly because Boon missed so many deadlines. Sometimes Roggeman drew the new episode mere minutes after he had been informed of the latest plot development, which gave him little time to think his artwork through. As a result, many of his drawings had to be rushed out, giving them a sloppy, wooden look.

Boon and Roggeman eventually left De Rode Vaan. Boon in particular was never a dedicated Communist and often argued with the die-hard Stalinists in the editorial board. Apart from ideological differences, the Rode Vaan was hardly a bestseller and had to save costs. And shortly after in 1946, Boon and Roggeman had their severe fall-out. In 1982, the 'Proleetje & Fantast' stories were collected in book form by Querido. Maurice Roggeman's nephew, Willem Roggeman, provided the foreword.