'Tailspin Tommy' daily of 4 October 1939.

Reynold Brown was an American illustrator and painter, famous for his posters for 1950s and 1960s Hollywood B-movies. Earlier in his career, he was an assistant-inker on Hal Forrest's 'Tailspin Tommy' strip (1935-1942), and then continued the series until its final episode. Renowned for his dynamic and sensational artwork, Brown improved the look of 'Tailspin Tommy' and many of his movie posters are still iconic today.

Early life and career

William Reynold Brown was born in 1917 in Los Angeles, California, as the son of a railroad engineer of German origins and a mother of Scottish descent. In primary school, the left-handed Brown was forced to write and draw with his right hand. As a result, he was later able to paint with both his left and right hand. In the late 1930s, Brown went to Alhambra High School, where his art teacher Lester Bonar was supportive of his talents and served as his mentor. Among Brown's graphic influences were J.C. Leyendecker, Dean Cornwell, N.C. Wyeth and especially Norman Rockwell.

Tailspin Tommy

While Brown was still in high school, the cartoonist Hal Forrest asked Lester Bonar if he knew a good artist who could assist him on the aviation newspaper comic strip 'Tailspin Tommy' (Bell Syndicate/United Feature Syndicate). Since Reynold Brown was both talented and crazy about airplanes, Bonar suggested his pupil for the job. After graduation, the former high school student became Forrest's ghost artist from September/November 1935 on. He started off as an inker, but eventually took over the pencil artwork too. Every week, Brown drove from San Gabriel to Palm Springs to deliver his drawings and was paid 30 dollar for them. His drawings were a vast improvement over Forrest's rather primitive and stiff artwork. Brown spent so much time on them that he actually had to take an inker-assistant himself, of whom only the name "Lloyd" is known.

'Tailspin Tommy' of 12 December 1939, presumably drawn by Reynold Brown.

On 15 March 1942, Brown quit 'Tailspin Tommy', which effectively meant the end of the series. Various reasons have been suggested for his departure. Forrest was known as a difficult and demanding man, whose former scriptwriter Glenn Chaffin had already left 'Tailspin Tommy' in 1934 over too many arguments. Not only was Brown's work uncredited, Forrest rarely showed appreciation. It could be that he just had enough. Yet somewhere between the late 1930s and 1941, a new topper comic was planned, which was to be credited to Brown: 'Stanley Stewart, War Correspondent'. The surviving artwork shows his name at the bottom of the pages. However this project seems to have stranded in the development phase. Brown's sister Lorraine claimed that 'Tailspin Tommy' had to close down under government pressure, because the comic depicted secret warfare tactics. Whatever the case, 'Tailspin Tommy' was already losing popularity by the late 1930s in favor of more contemporary aviation newspaper comics.

Around this period, Brown's old high school teacher introduced him to her brother, the famous painter/illustrator Norman Rockwell. Rockwell advised Brown to give up comics if he ever wanted to be taken seriously as an illustrator. This seems to have been his strongest motivation for quitting. Indeed, Brown never made another comic strip in his career. Some time later, he won a scholarship for the Otis College of Art and Design in Los Angeles.

The P-47 Thunderbolt, by Reynold Brown.

World War II

From May-June 1942 on, Reynold Brown did his patriotic duty during World War II. Together with fellow artist Mary Louise Tejeda, he was in charge of sectional and cutaway drawings of aircrafts at North American Aviation. The couple got married in 1946. Around the same time, Brown's technical airplane drawings ran in Skyline, Popular Aviation and Flying Magazine. He also drew advertisements for Mobil Oil.

Post-war period

After World War II, Brown and his wife moved to New York City. He was much in demand as an illustrator of paperback book covers for Signet and Pocket Books, while his drawings also appeared in the magazines Argosy, Boys' Life, Outdoor Life, Popular Science and the Saturday Evening Post. By 1951, the couple returned to California, where Brown became a teacher in figure drawing at the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena. Among his better known pupils were sculptors Hollis Williford and Richard MacDonald, painters Gordon Snidow and John Asaro, and illustrators Robert Peak and Dru Struzan. Between 1961 and 1963, he made nine paintings for The United States Air Force Art Collection, specifically about operations in the Japan and Okinawa area. Brown was also a long time member of the Los Angeles Society of Illustrators.

Film poster for 'The Incredible Shrinking Man' (1957).

Film posters

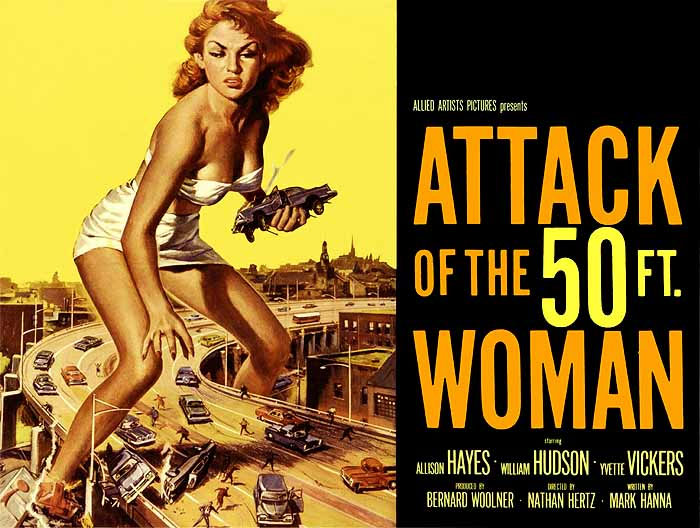

Through Misha Kallis, art director at Universal Pictures, Brown received regular commissions to design film posters. He made breathtaking realistic artwork to advertize B-horror movies like 'Creature from the Black Lagoon' (1954), 'Tarantula' (1955), 'This Island Earth' (1955), 'The Incredible Shrinking Man' (1957), 'I Was a Teenage Werewolf' (1957), 'The Deadly Mantis' (1957), 'Attack of the 50 Foot Woman' (1958), 'House On the Haunted Hill (1958) and 'The Time Machine' (1960). His imagery tingled people's curiosity and was often far more thrilling and scary than the picture itself. Partially thanks to his memorable posters, several of these pictures became cult classics. In some cases, like 'Attack of the 50 Foot Woman', the posters are arguably more iconic than the film itself.

While Brown's work is often associated with shlocky camp, not all movies were that bad. In fact, he also designed posters for more prestigious films, such as 'Cat On A Hot Tin Roof' (1958), 'Ben-Hur' (1959), 'Spartacus' (1960), 'The Alamo' (1960), 'King of Kings' (1961), 'How The West Was Won' (1962), 'Mutiny on the Bounty' (1962) and 'Dr. Zhivago' (1965). Sometimes his artwork promoted foreign pictures as well, such 'La Maschera del Demonio' (also known as 'Black Sunday', 'The Mask of Satan', or 'The Revenge of the Vampire', 1960), 'Reptilicus' (1961) and 'Mothra vs. Godzilla' (also known as 'Godzilla vs. the Thing', 1964). Brown made more than 250 film posters, which were hung outside film theaters, inside lobbies and printed in promotional flyers and magazines. They are still popular among cinephiles and fans of 1950s-1960s memorabilia.

For comic historians, his posters for 'The Creature Walks Among Us', 'The Incredible Shrinking Man', 'Love Slaves of the Amazons' and 'How the West Was Won' are interesting, because Brown made use of sequential images to describe parts of the story.

Poster for the film 'Attack Of The 50ft. Woman'.

Final years and death

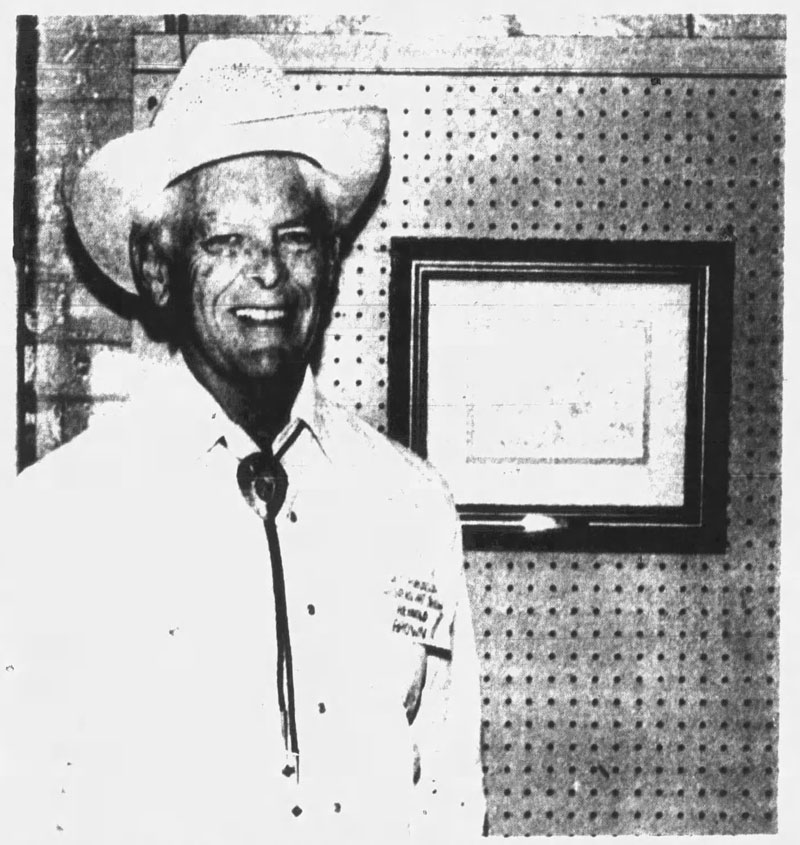

In the early 1970s, Reynold Brown left the film poster business, because he lost touch with new trends in movies. He focused on western-themed paintings to be sold on the fine art market. Unfortunately he became victim of a serious stroke, which left the left side of his body paralyzed. With the help of his loving wife, he was still able to make new paintings, but at a slower pace. In 1983, the couple moved to Chadron, Nebraska, where Reynold Brown passed away in 1991 at age 73.

Secondary literature

Brown's life was subject of a documentary, 'The Man Who Drew Bug-Eyed Monsters' (1994), directed by Mel Bucklin. For those interested in Brown's career, the book 'Reynold Brown: A Life in Pictures' (2009) by Daniel Zimmer and David J. Hornung is highly recommended.

Reynold Brown in 1981 (The Chadron Record and Crawford Tribune, 1 August 1981).