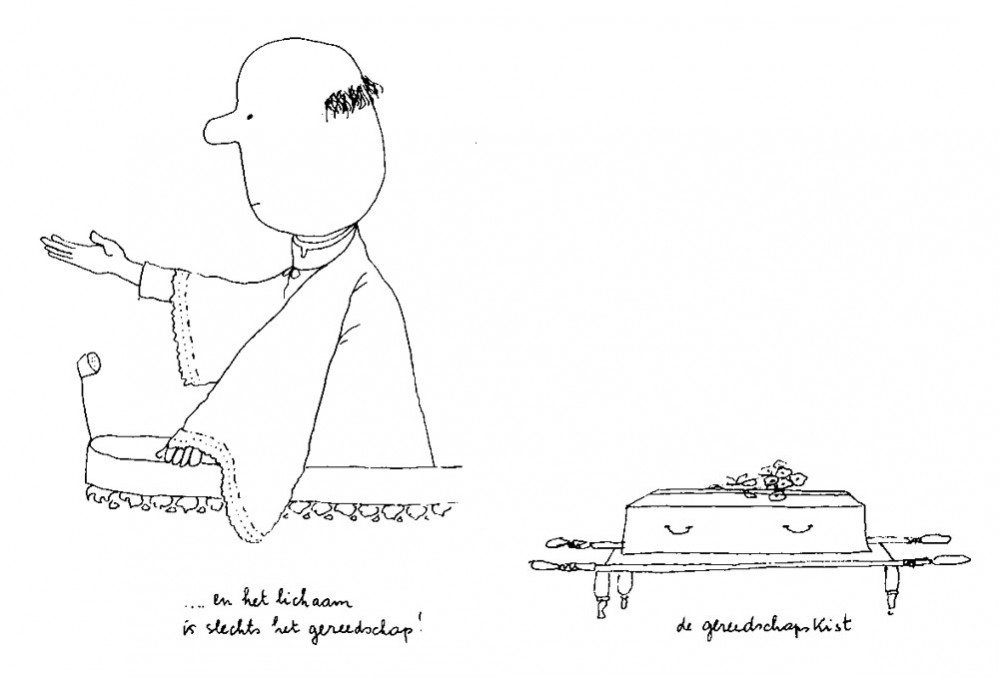

From: 'Clownerietjes' (1979). "...And the body is just a tool." "The toolbox."

Toon Hermans was a legendary Dutch comedian, cabaret artist and singer. One of the most popular and influential humorists of his day, he shaped the post-war Dutch cabaret scene by introducing a one-man act show, which were even further popularized through their broadcasts on the new TV medium. He brought light-weight, observational comedy and was a master in seeing the fun in everyday things and situations. Outside of his long showbiz career, Hermans was a painter, poet and cartoonist. Some of his cartoons adorned his personal poetry books, while his 'Clownerietjes' books offered pure humorous drawings, some of which are sequential.

Early life and career

Antoine Gerard Theodore Hermans was born in 1916 in Sittard in the Dutch South Eastern province of Limburg. Although he often presented himself in public as a folksy boy from a simple working class background, in reality his father was head of a local bank. However, Hermans did experience misery and poverty in childhood when his father went bankrupt in 1924 through bad speculations, and passed away three years later. At age 12, Hermans and his siblings were suddenly forced to grow up and get a job to survive. As a youngster, he decorated shop windows, wrote little poems and drew cartoons, which he sold door-to-door and to stores. In his heart, Hermans aspired to become an entertainer. Among his main humorous influences were Lou Bandy, Louis Davids, Charlie Chaplin and the clown Johan Buziau. Later in his career, he also expressed admiration for Victor Borge, Wim Kan, Danny Kaye, Oleg Popov, Van Kooten en De Bie, Jacques Tati and Bert Visscher. Musically, he drew inspiration from Maurice Chevalier, Yves Montand and Richard Tauber.

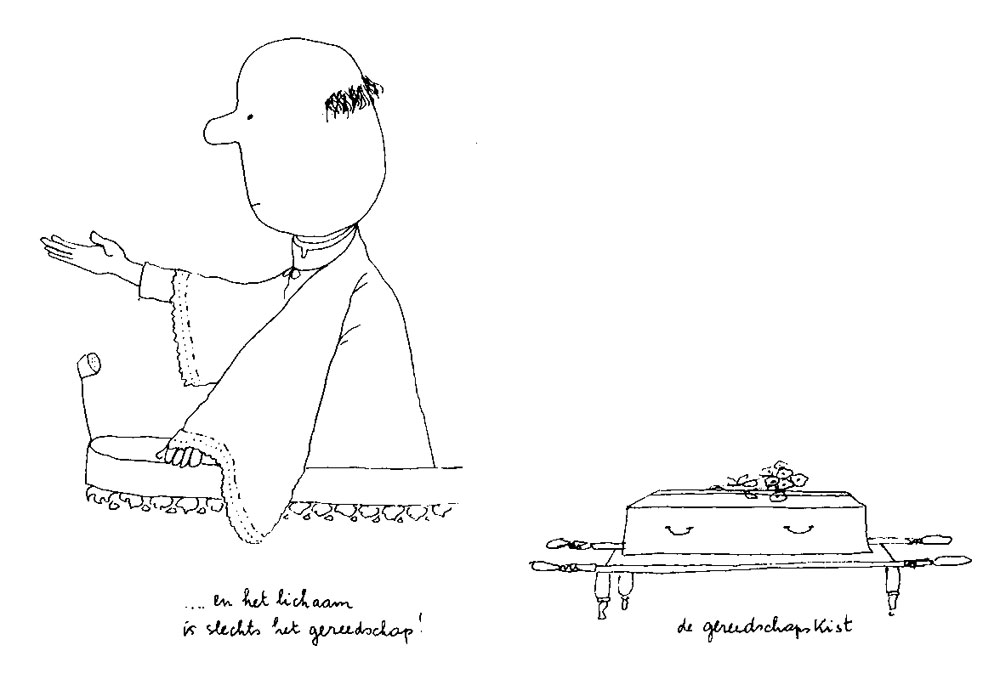

Cartoon by Toon Hermans. Translation: "What do you want to be when you grow up?", asked the teacher. It was in third grade. I looked at her and didn't know. I thought I already was something."

Starting out in small bars and performing during the annual carnival festivities in Limburg, Hermans became a local celebrity. Through correspondence with one of his idols, Johan Buziau, he was able to hone his craft. In the 1940s, he moved to Amsterdam, where he played in various cabaret groups and increased his national fame by being broadcast on public radio. In 1955, Hermans started a solo career. He made evening-filled theatrical shows, which, from 1958 on, were broadcast in their entirety on television. He also released audio recordings of these shows on vinyl records. In an era when the public network was the only channel and video recorders weren't commonplace yet, his shows and records sold out, while TV broadcasts drew high ratings. Hermans became one of the most popular comedians of the Low Countries. Together with Wim Kan and Wim Sonneveld, who soon also jumped on the TV bandwagon, he was hailed as one of the “Big Three of Dutch Cabaret”. Several of his skits, like 'Leg Neer Die Bal', 'Snieklaas' and 'Duif Is Dood' became classics. Hermans also recorded various songs, some humorous, like 'De Tango van het Blote Kontje' and 'Mien, Waar Is Mijn Feestneus?', others sentimental, like '24 Rozen' and 'Méditerranée' (1958).

Hermans tried to expand his audience by performing abroad in Belgium, Germany, Austria, Canada and even a 1968 Broadway show. He had modest success, but felt the foreign theater industry was too overwhelming and business-like. In the end, he preferred the cosy familiarity of performing in the Dutch-language countries. Outside of the Netherlands, Hermans was particularly beloved in Flanders, where audiences almost regarded him as his own. After all, he was a Catholic, his comedy was mild and he hailed from the Dutch province of Limburg, close to the Belgian province of the same name. Since Hermans barely referred to specifically Dutch topics, Flemings received him far better than other Dutch comedians, whose frame of reference remained too local to be properly understood.

One-man shows

Hermans innovated Dutch comedy in many ways. Up until the mid-1950s, most Dutch comedians either performed as a duo, or as part of a larger ensemble or variety show. In 1956, he pioneered the concept of a “one-man show”, where he entertained audiences completely on his own for a full evening, only accompanied by an orchestra. In other countries, this was already a well-established phenomenon, but in The Netherlands it was so unusual that few believed anyone could pull this off. Once Hermans proved it was possible, it quickly became the standard format for almost all Dutch cabaret artists.

Like other Dutch cabaret artists, Hermans alternated sketches and skits with musical intermezzos. But contrary to them, he wasn't a socially conscious performer. He kept his comedy apolitical and devoid from any heavy-handed statement or reference to current events. Hermans saw the world as a wonderful, fascinating place. If he had any message at all, he wanted people to experience the joy and wonders of life. The comedian brought people's attention to seemingly banal topics and made them look at them with amusement. He built entire performances around something as ordinary as his sister's easy chair, or an observation of a man eating a peach. He found comedy in plain, everyday objects, like a collection of funny hats he brought along with him. General audiences loved this inviting, light-hearted, non-offensive, family friendly style. Critics, on the other hand, felt his comedy lacked substance. Most of the time, there weren't real “punchlines”. The laughter came from the way he presented and told things, rather than actual jokes. His beaming face and proverbial joyfulness were so “infectious” that audiences already cheered up when he simply walked on the stage. It often seemed as if he just made up stuff as he went along, resulting in a lot of filler that could have easily been condensed into shorter, tighter skits. Hermans added to this public image by claiming: “I just do something, nothing very special.”

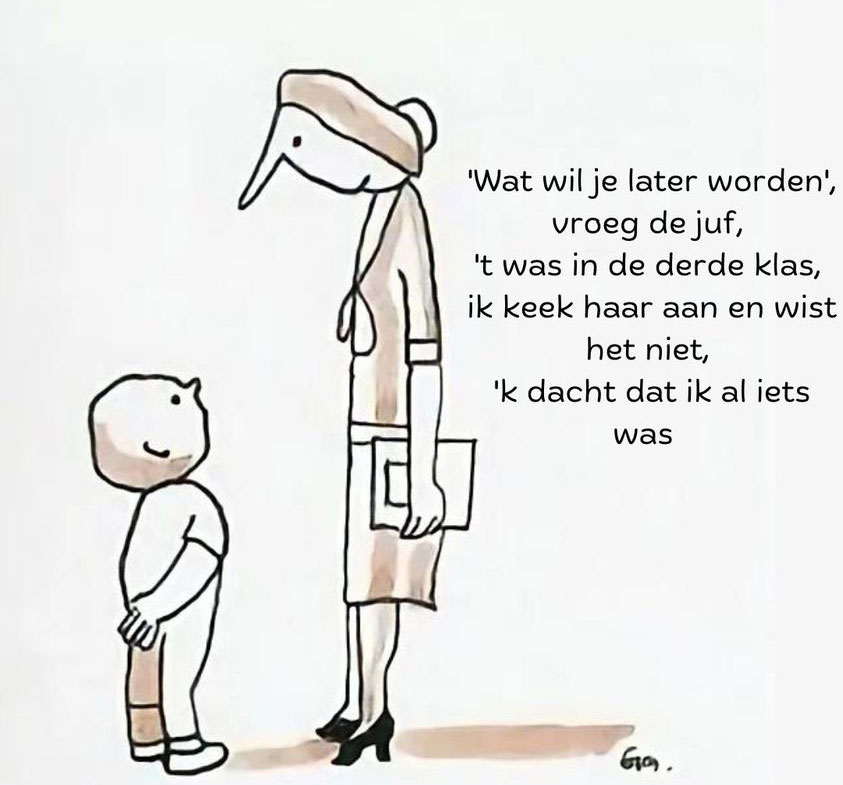

'Happiness'.

Hermans didn't consider himself a genuine cabaret artist. In his opinion, he was a clown outside a circus, keeping his humor simple and a little tragi-comical. He acted as if he merely pondered about things, while in reality he recited a carefully prepared and memorized monologue. Fellow comedians admired his ability and audacity to entertain people with material that doesn't seem particularly inspired or hilarious in itself, but became genuinely witty once he put his personal spin on it. A typical example is his parody of a magician, whose “magical tricks” are all plain things anyone could do, only presented more spectacularly. Another iconic moment, from his 1980 show, has him ask a stagehand (his son, Maurice) to bring him a tennis racket and a ball, whereupon Hermans does nothing until the man returns with this object, walking circles, humming in himself, but barely addressing the audience. Hermans would stretch this kind of nothingness for minutes, while keeping everybody roaring in the aisles.

Behind the scenes, Hermans was a perfectionist who was very protective of his public image. He could be very insecure and bossy, rewatching and analyzing his stage rehearsal video recordings after the show, and even during the half hour break in between. Yet the general public wasn't allowed to see this side of him. Hermans presented himself as a common, modest everyman, who didn't seem to understand the modern world. He entertained people with witty nonsense and simple philosophies, telling them to cherish the small things. As he grew older, Hermans was compared to a charming grandfather figure, telling corny, old-fashioned puns and just acting silly for the fun of it. On stage and during interviews, he avoided sex jokes, vulgarities, topical comedy, complicated language or mean-spiritedness. In private, he was actually well-read, very opinionated and followed the latest developments far better than he let on to the general public.

From: 'Clownerietjes' (1979). Fireman with a "fikkie" (slang for "fire"). Again fireman with Fikkie ("Fikkie" is a typical Dutch dog name).

Graphic and literary work

In his spare time, Hermans wrote short poems, which he dubbed his “verses”. They are typically simple reflections on life, mankind, nature, happiness or the benefits of being nice to each other. Some were only a few lines long. The comedian used them during his stage shows, but they were also printed on greeting cards, calendars and tiles. Hermans also made them public in books, and to liven up the pages he often added personally drawn cartoons. All were simple line drawings, close to doodles, which visualized the themes of his poetry. Hermans' artwork appeared in his books 'Kladboek' (1953), 'Waar Ben Je?' (1980), 'Vandaag Is De Dag' (1987), 'Verzamelde Versjes' (1989), 'Geluk' (1990), 'Liefde' (1990), 'Een Boom Opzetten' (1995) and 'Wijsheid en Andere Versjes'. Some of his books were made with the participation of his cartoonist friend Ted Schaap, AKA Scapa, who also designed some of his theatrical posters.

'De laatste blootjes wegen het zwaarst'. From: 'Clownerietjes' (1979).

In 1975 and 1979, Hermans brought out two books with straightforward humorous cartoons and occasional sequential illustrations, titled 'Clownerietjes' (”Clowneries”). All drawings are accompanied by a corny pun. For instance, a drawing of a weightlifter is described as an “oplichter” (literally “somebody who lifts something”, but an “oplichter” is also Dutch for “scammer”). A family of nudists, with the children walking up front and a father and an uncle follow behind them, is described as “the laatste blootjes wegen het zwaarst”, a pun on the expression “the laatste loodjes wegen het zwaarst” (“the final load is the heaviest”, with the word “blootjes” referring to “nakedness”). Thanks to Hermans' fame, the 'Clownerietjes' sold well. His crude drawings can be compared with similar rudimentary cartoons and comics by other Dutch celebrities like Wim de Bie, IJf Blokker, Herman Brood, Remco Campert and Jan Cremer. In a TV interview, Hermans said that he was inspired by children's drawings, since kids don't overthink their “art”. In his opinion, adults like him could imitate these primitive scribblings, but not achieve the same level of spontaneity.

Many of the things that Hermans told to journalists and audiences often seemed true revelations and anecdotes, but in reality most were romanticized stories, intended to keep his myth of an ordinary everyman intact. His drawings fell in the same category, being presented as the work of an average Joe whose graphic skills were as simple as his musings about life. In reality, Hermans was a far more accomplished artist. In his spare time he made very realistic landscape paintings, depicting nature in and around his hometown. As a devout Catholic, he felt that the splendor of forests, grassy fields and rivers expressed God's greatness far better than well-intended religious ceremonies. He admired Marc Chagall, Charles Eyck, Constant Permeke, Bram van Velde and Kees Verwey. Hermans regarded painting as a hobby and a way to let off steam. He didn't want to make his canvases public, since they were just intended to give him some mental rest. The majority weren't even signed. Only relatively late in his career, a book compilation, 'Toon Hermans, Schilderijen, Tekeningen, Gedachten' (1995), came out, which instantly became the best-selling art book in the Low Countries of that year. A posthumous exhibition, 'Toon Hermans Levenskunstenaar' (2001) was held in the Singer Museum in Laren, followed by another one in 2005, 'Mariablauw, Boerderijenwit, Klaproosrood. Honderd Schilderijen van Toon Hermans' in the Kunsthal in Rotterdam.

Final years

Hermans remained successful throughout the decades. In 1965, he was knighted in the Order of Orange-Nassau. After the death of Wim Sonneveld (1971) and Wim Kan (1983), he was the only one of the “Big Three of Cabaret” left, which increased his stature. To many people, Hermans was the “grand old man” of his profession. An entertainer who had been in the business for so long that several people hadn't even been born when he debuted. To younger generations of comedians, he sometimes acted as an elderly mentor. He gave them professional advice and his personal opinion about their performances.

After the death of his beloved wife Rietje in 1990, Hermans was heartbroken. In 1996, the 80-year old veteran gave his final show. At that point, he was the longest active stage comedian in his home country. Four years later, he wanted to release a CD-only comedy show, but died during the Spring of 2000. The CD, 'Als De Liefde' (2000) was released posthumously. Hermans' death made headlines in The Netherlands and Flanders, where he was hailed as a genius and trendsetter. His legacy is guarded by the Toon Hermans Foundation.

Legacy and influence

Since Toon Hermans was a mainstay in Dutch theatre and television for most of the second half of the 20th century, his comedy reached a wide audience. His shows have also been repeated far more often on TV than several of his contemporaries, since his humor is so timeless and easy to understand without preconceived knowledge. He has been cited as an influence by Dutch comedians like Vincent Bijlo, Herman Finkers, Seth Gaaikema, Freek de Jonge, Brigitte Kaandorp, Paul de Leeuw, Hans Liberg, Jochem Mijer, Youp van 't Hek, Kees van Kooten, Herman van Veen, Paul van Vliet and Ivo de Wijs, and by Flemish humorists like Warre Borgmans, Geert Hoste, Guy Mortier, Bart Peeters and Mark Uytterhoeven.

In 2003, Hermans received a statue in front of the local theatre in Sittard, sculpted by Loek Bos. In 2005, he was elected to a 22th place in the “Greatest Dutchman” contest. His life was also adapted into a 2010 musical by Albert Verlinde. In 2021, the local theatre in Sittard was renamed the Toon Hermans Theater. Toon Hermans' portrait was painted by Jan Kruis for Jojanneke Claassen's series 'Dubbelportretten' in the women's magazine Libelle. Hermans' comedy is also admired by 'Kiekeboes' creator Merho.

Books about Toon Hermans

For those interested in Toon Hermans' life and career, Jacques Klöters' biography 'Toon. De Biografie' (Nijgh & Van Ditmar, 2010) is highly recommended.