For the special anniversary issue accompanying Eppo magazine #40 of 1980, Richard's Studio created an argument in comic format between a hand-written letter and a typeset letter.

Richard Pakker was a Dutch comic letterer and production artist, active from the 1960s through the 1990s. With about twenty employees, His business, "Richard's Studio," employed roughly twenty employees and provided the lettering for the major Dutch comic magazines, including Pep, Sjors, Eppo, Donald Duck and Tina.

Early life

Richard Pakker was born in 1931 in Amsterdam. A high school dropout, he prefered drawing over studying and decided to become an illustrator. Shortly after World War II, he found employment at Marten Toonder's studio, where he was introduced to the world of comic production. He spent one year at the studio as an apprentice inker, until he was drafted into military service. Back in civilian life, Pakker attended the Amsterdam Academy of Fine Arts, alongside fellow student and future graphic artist Aat Veldhoen. Between August 1954 and February 1955, Pakker joined his journalist friend Koen Aartsma on a motor scooter journey through the Scandinavian countries. The two young men sent their reports, written by Aartsma with photographs by Pakker, to the newspaper Friese Koerier.

Second part of the 1980 argument strip.

Comic book lettering

After returning to the Netherlands, Pakker spent a year working as a comic artist at Studio Wienk.He got married, settled in Amsterdam's Watergraafsmeer district and eventually switched to full-time comic lettering, initially for Swan Features Syndicate, where he filled the speech balloons of imported comic strips with translated texts. By 1956, he had his own lettering and advertising studio, which became known as "Richard's Studio" or "Studio Pakker". One of the studio's most important clients was the publishing house De Geïllustreerde Pers, which in 1962 launched the comic magazine Pep. To give the new title a different look from other comic magazines, Pep's editors decided to use hand lettering in their comics, rather than the standard typeset letters. As the in-house letterer, Pakker specialized in what he called "miniature calligraphy", which not only included dialogues in speech balloons, but also expressively drawn onomatopoeia (sound effects). Pakker's hand lettered texts were written out in India ink on a sheet of paper, then cut out and carefully pasted inside the speech balloons on the comic page. Pakker also reformatted and edited artwork of foreign comic strips to make them suitable for Pep's page layout.

Richard's Studio in Amsterdam-Oost.

Richard's Studio

In the upcoming Dutch comic industry of the 1960s, Pakker became an expert in his trade. Besides Pep, he provided lettering for other comic magazines published by the VNU group. For decades, Richard's Studio lettered all the comics in Pep, Sjors, Eppo, Tina, Donald Duck and the other Dutch Disney publications. With assignments piling up, Richard's Studio began expanding. Initially, Pakker collaborated with his wife, Geesje Wortel, but by the mid-1960s, six additional employees were brought on to keep up with the workload. One of Pakker's first hires, Meini Gouwenberg (1942-2021), was a former letterer for publisher De Spaarnestad who remained with Richard's Studio for decades to come. Another longtime employee was Rini van Broekhoven (1948-2018). At the peak of his studio's output, Richard Pakker had twenty people working for him, among them Klaas Groot, Jaap Vermeij, Mark de Jonge, Peter de Wit and Rudi Jonker. Besides comic lettering, the team provided lay-outs and production art for advertisements, crossword puzzles and knitting patterns for women's magazines.

Hand-lettered font designed by Meini Gouwenberg for Donald Duck weekly in 1986 (left) vs. digital lettering in 1988 (right).

During the 1980s, Dutch comic magazines struggled with declining circulation figures. From 1981 on, Studio Pakker had competition from Peter de Raaf, who also ran a studio specialized in comic book lettering. Pakker realized that lettering by hand became too expensive, and invested in a typesetting machine controlled by a computer. From 1987 on, all the in-house fonts were digitized, allowing the studio to save time and publishers to manufacture the lettering themselves. By making two versions of the same letter with slight variations, the end result still gave the impression of hand lettering. The lower case font the studio used for Donald Duck weekly is still in use today. In 1992, Studio Pakker also made the characteristic character headers that open each Disney story, modeled after the headers of the classic American 'Donald Duck' stories by Carl Barks.

Retirement and the post-Pakker period

Richard Pakker retired in 1996, leaving his studio to his employees Rini van Broekhoven and Jean Magrijn. By then, long-time employee Meini Gouwenberg had already left the company to form his independent Studio Meini. From the 1980s until his retirement in 2008, Meini provided the lettering for Don Lawrence's 'Storm' and the Disney book publications. His studio was then taken over by the graphic design studio Fecit Vormgevers, that continues to provide the lettering for the Dutch Disney pocket books. Rini van Broekhoven ran Studio Pakker until 2002, then continued lettering under his own "Studio R" banner. Van Broekhoven provided lettering for the comics in the Disney magazines, Tina and Zo Zit Dat until he retired in mid-2018, due to health reasons.

Recognition

To honor his contributions to the Dutch comic industry, Het Stripschap awarded Pakker the 2013 Bulletje & Boonestaak Plate, which was presented to him during that year's Stripdagen comic festival by acclaimed comic book handletterer Frits Jonker. Until the end of his life, Pakker has resided in his old house studio, where he spent his time digitizing old slides and writing rhymes and epigrams.

Death

In 2023, Richard Pakker passed away at age 92. A few months earlier, between 22 Juli and 6 August 2023, an exhibition about his studio was on display at Galerie Weerdruk on the Entrepotdok in Amsterdam in the presence of his daughter. At that point, Pakker was already too ill to attend the ceremony.

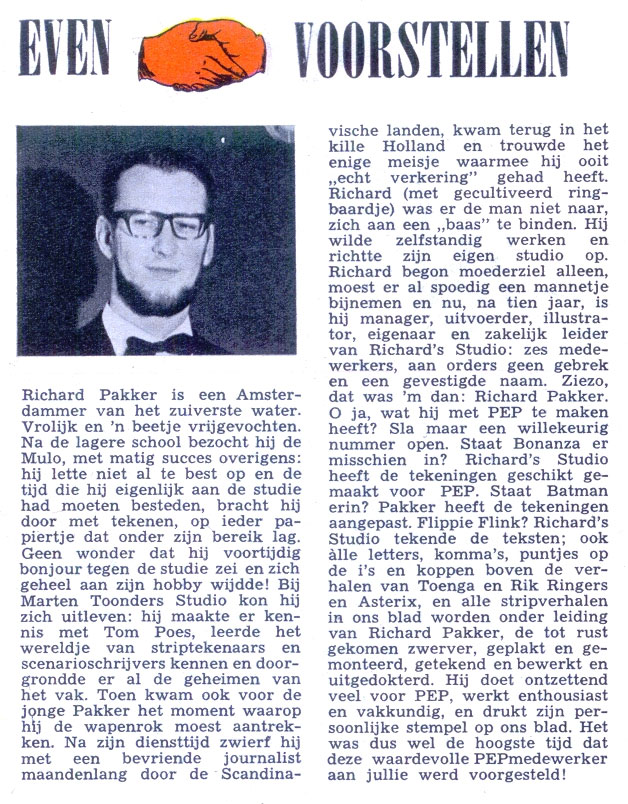

Pep magazine often introduced its regular co-workers to the readers. In issue #3 of 1967, it was Richard Pakker's turn.