'A French Dentist Shewing a Specimen of his Artificial Teeth and False Palates' (26 February 1811).

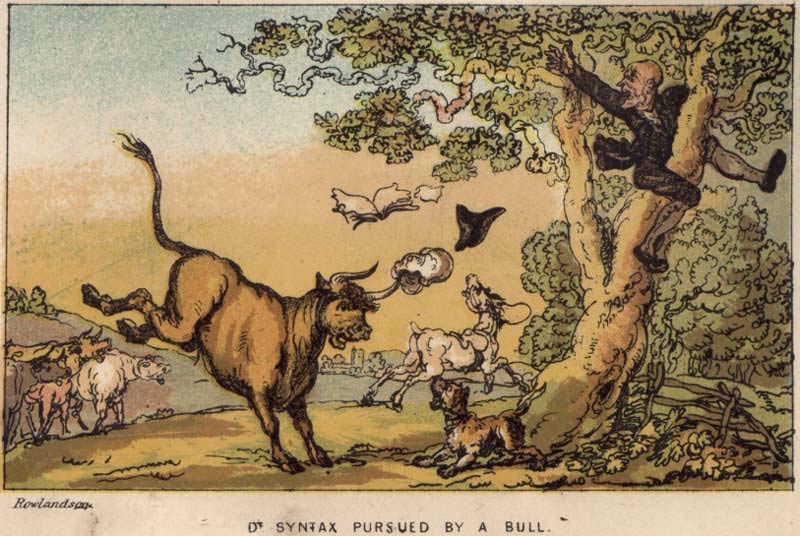

Thomas Rowlandson was a late 18th-century, early-19th century British cartoonist and caricaturist, regarded as one of the greatest in his field. He drew grotesque, often vulgar, but always hilarious caricatures of people and situations. He satirized his own era, entertaining and polarizing audiences at the same time. A productive artist, he also livened up the pages of many books, while simultaneously providing a lot of erotic and pornographic illustrations. Rowlandson was also a notable comics pioneer. Some of his illustrated novels, particularly John Mitford's 'Johnny Newcome' (1818) and William Combe's 'Dr. Syntax' (1812-1821) can be regarded as a prototypical comic series built around one recurring protagonist. 'Dr Syntax' is even the first example of a comic character used in merchandising. Many of Rowlandson's cartoons have made use of word balloons and sequential narratives.

Early life and work

Thomas Rowlandson was born in 1757 in London. His father was a weaver who worked in the textile trade, but went bankrupt when little Thomas was two. Through his uncle and aunt, the boy was still able to study at the Soho Academy (1765-1772), even though he filled his school books with caricatures of his teachers. Rowlandson ranked Thomas Gainsborough and Peter Paul Rubens as his favorite painters, and in the field of caricature he was influenced by James Gillray, William Heath and Giovanni della Porta. At age 16, Rowlandson left for Paris, where he spent two years studying arts at a local academy (recent sources like Stephen Wade's 'Rowlandson's Human Comedy' [2009] have narrowed this often repeated "fact" down to a mere few weeks). Back in London, in 1772, Rowlandson spent six years at the Royal Academy. In 1777, he opened a studio in Wardour Street and became active as a portrait painter. He made several water color paintings and engravings which depicted idyllic and rustic scenes of nature.

Caricatural work

After the death of his aunt in 1789, Thomas Rowlandson could no longer rely on financial aid from his relatives, especially after spending most of her inheritance on gambling. He remained addicted to placing bets throughout his entire life. To pay off his debts, Rowlandson decided to become a caricaturist. Since he always needed money fast, he was quick and productive. Throughout his life, he made over 10,000 drawings and prints. To save time, he sometimes recycled older designs, giving some of his work a rushed appearance. The majority, however, are magnificently rendered and feel fresh and spontaneous. Rowlandson was a master in exaggerating people's facial features. Many of his characters have a grotesque, and often repulsive look. He had a knack for people with bloated faces, big noses and podgy bodies. The expression "warts and all" could have been his life's motto. Every zit, wart, ulcer, is depicted, complete with hairs. Even today, centuries later, his audacious cartoons still make people laugh.

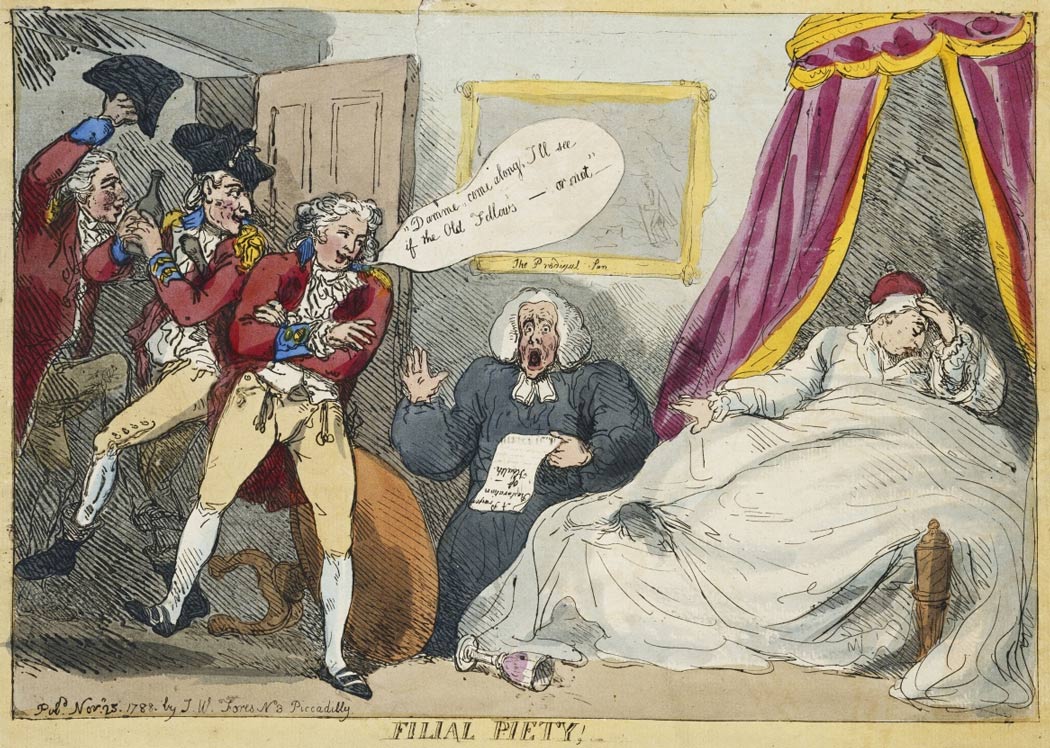

'Filial Piety' (1788). Prince George (later king George IV) checks whether his father, George III, has passed away yet, so he can succeed him.

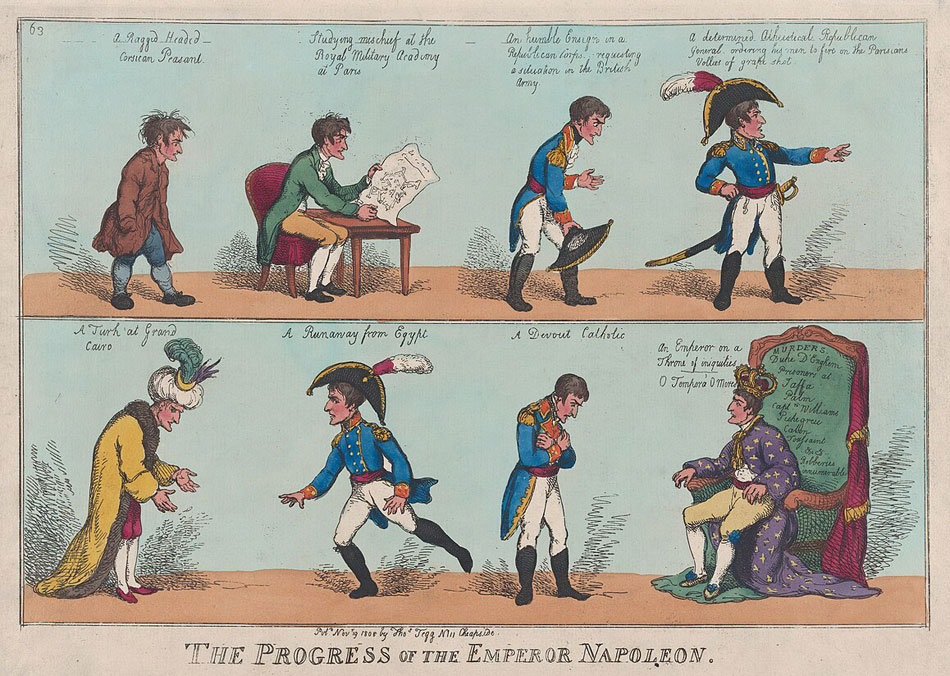

Rowlandson's satirical cartoons were published in magazines like The English Spy, The English Review, The Humorist and The Poetical Magazine, often aquatint on copper plate. His publisher was Rudolph Ackerman. A versatile commentator, Rowlandson mocked fashions, doctors, alcoholics, couples, politicians and even the British Royal Family. He mercilessly lampooned Prince George (the later King George IV) and his mistress, even going so far as to make a cartoon, 'Filial Piety' (1788), in which King George III lies on his death bed, while the young prince happily walks in to check whether his father is dead yet. On the other hand, Rowlandson made no qualms about integrity. When Prince George asked him to draw cartoons that depicted him in a better light, Rowlandson simply accepted the offer and the payment. And as much as he ridiculed English society, he also showed his patriotic side during the Napoleonic Wars, drawing many cartoons that ridiculed Napoleon Bonaparte.

'The Progress of the Emperor Napoleon' (1808).

At the time, Rowlandson was mostly popular with the common people and those rare upper class people that were willing to admit his talent. Many, however, also criticized him for making such vulgar cartoons, particularly his erotic drawings. Even George Cruikshank felt that Rowlandson wasted his talent: "Rowlandson had suffered himself to be led away from the exercise of his legitimate subjects, to produce works of a reprehensible tendency."

'Two New Sliders For The State Magic Lanthern' (1783).

Prototypical comics combining word balloons and panels

Thomas Rowlandson made a huge amount of cartoons which use word balloons or sequentially illustrated narratives. In some cases, he combined the two. 'Two New Sliders For The State Magic Lanthern' (29 December 1783) was a satirical take on the coalition government of Lord Fox and Charles James North, presented as a series of slides to be projected from a magic lantern. The work is notable because it depicts a narrative told in ten sequences clearly separated by frames. The entire story takes up two strips. Each scene has a description written underneath it. There is also anthropomorphism at play, since Lord Fox is depicted as an actual fox. Rowlandson made another comic strip-like cartoon about the two politicians, namely 'The Loves of the Fox and the Badger, or the Coalition Wedding' (7 January 1784), which depicted them as a fox (Lord Fox) and a badger (North) who are wed in matrimony by Satan. The entire story is told in nine separate frames, divided over two strips. Much like the previous work, descriptive sentences appear underneath the images, but there are also characters using word balloons. In the second and third image above, there is even a primitive suggestion of thought balloons, to indicate that both the protagonists have a dream.

'The Loves of the Fox and the Badger' (1784).

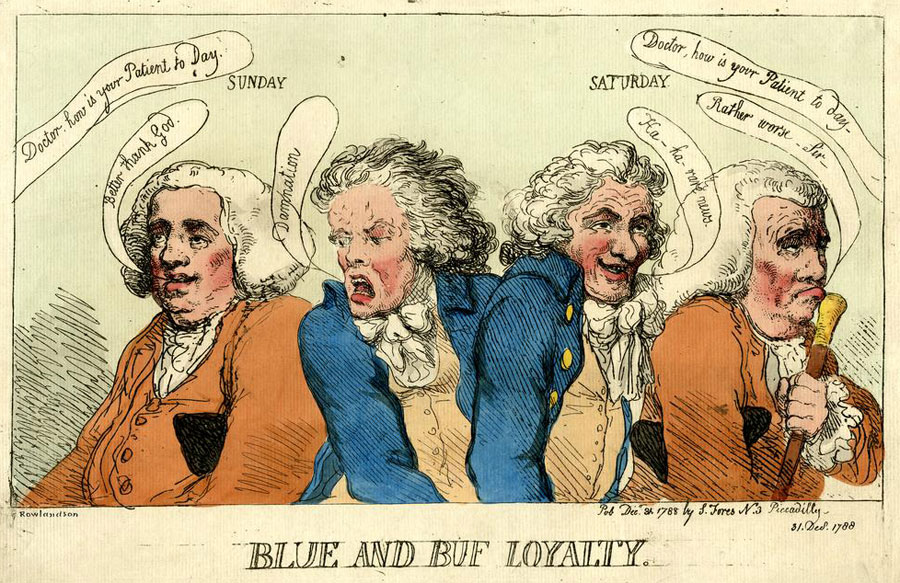

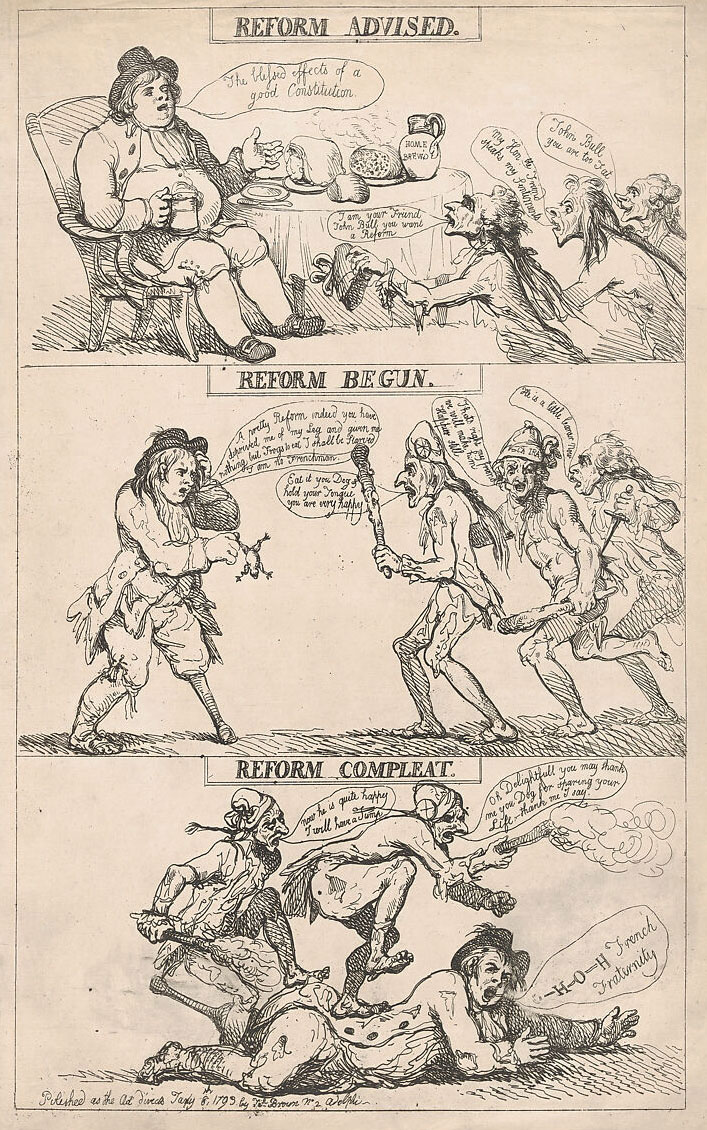

Rowlandson's cartoon 'Blue and Buf Loyalty' (1788) mocked the politician Richard Brinsley Sheridan and King George III's personal doctor Willis and their opposite reactions to the monarch's declining health. To indicate a passing of time, the word "Sunday" is written in the left corner, while in the right corner the word "Saturday" is written. Rather than frame these time sequences by separating the images, both men are shown standing next to each other, giving them the confusing appearance of being four different men, instead of the same two men depicted twice. Both express their emotions in word balloons, as does the off-screen announcer who informs them about the king's mental state. In 'Reform Advised, Reform Begun, Reform Complete' (8 January 1793), a three-panel comic strip shows how the British national personification agrees to give a group of rebels reforms, only to be trampled by them afterwards. Their dialogue is depicted in word balloons. The work is a fierce criticism of the ideals of the French Revolution, with John Bull exclaiming: "O-h-oh French fraternity".

'Blue and Buf Loyalty' (1788).

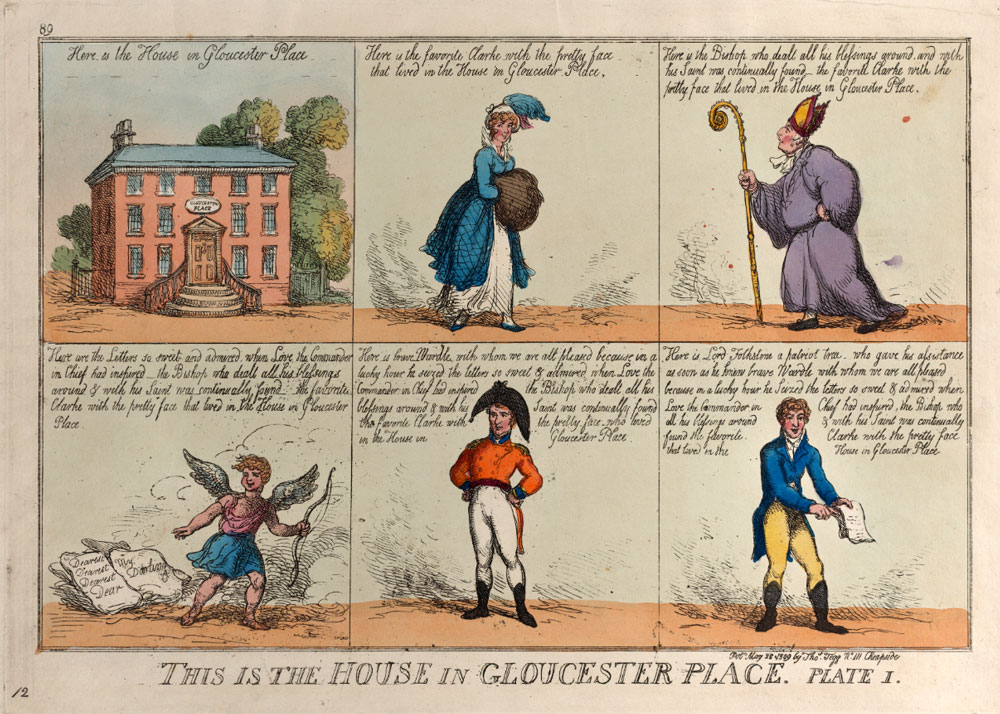

'This Is The House In Gloucester Place', printed on 26 May 1809, was another interesting prototypical comic strip. It explained all the key people in a political scandal that broke out that same year. Mary Anne Clarke, the mistress of Frederick, Duke of York, was known for her decadent lifestyle. In their luxurious Gloucester House home she soon needed extra money. In full knowledge she could convince her lover, she accepted large sums from military officers. However, this was technically bribery. When the scandal broke out, it brought the Duke under direct investigation of a special committee. It didn't help matters much that Mary Anne published the book 'The Rival Princes', in which she freely discussed her motivations and accused the people who had leaked the scandal, namely Wardle (Member of Parliament for Salisbury) and Lord Folkestone. They sued her for libel, but lost their case. When she threatened to publish her written correspondence with the Duke, Sir Herbert Taylor bribed her and destroyed all evidence, except for one copy. Meanwhile, the Duke was acquitted, but his reputation was so tarnished that he was still forced to resign as commander-in-chief. He instantly broke off his relationship with Mary Anne. She was later sued for libel, based on what she wrote in another book, 'A Letter to the Right Hon. William Fitzgerald'.

'This Is The House in Gloucester Place' (1809).

Rowlandson starts off his comic strip with a shot of Gloucester House, where the Duke and Mary Anne resided. Then he introduces everybody and everything involved with the scandal by depicting them in a panel, with lengthy explanations above and below the images. First Mary Anne, then the bishop, the letters between her and the bishop, Wardle who seized the letters, Lord Folkstone, Francis Burdett, Dodor O'Meara, Dowler, the volumes about the lives of Mary, the printer and the bonfire that burnt the evidence. The entire comic strip was so long that Rowlandson used two pages to draw it.

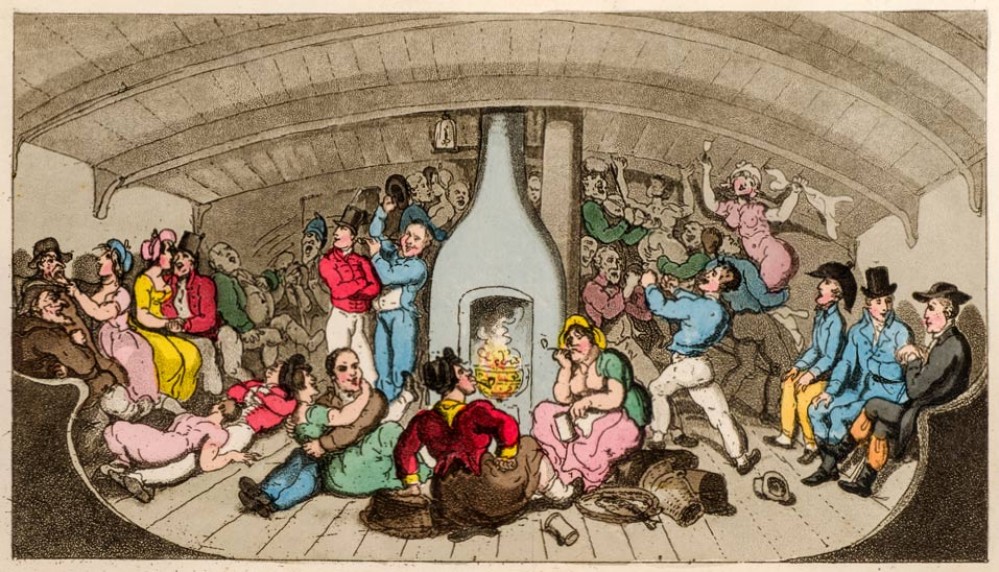

Another one of Rowlandson's house-related picture stories based on real events was 'This Is The House That Jack Built' (27 September 1809), spoofing the English nursery rhyme of the same name. Every panel has a rhyming narrative, handwritten underneath the images. This makes it a text comic, though some panels have word balloons too. The comic satirized riots which took place at the Theatre Royal in Covent Garden, London, a week earlier. On 18 September 1809, the theater had opened to the public after the building had burned down a year earlier. This made the tickets more expensive than usual and many theatergoers were understandably not too happy about it. People started to protest outside the building and theater owner John Philip Kemble was forced to send in the police. However, the riots kept going. Some people who paid for tickets only entered the theater to continue disrupting the performances with banners and by shouting for lower prizes. Rowlandson depicted these events in six panels, with Kemble (the "Jack" from the title) himself appearing in the final image. Nobody could suspect that these riots would continue for three months in a row, with twenty people dying in the uproar. Eventually Kemble was forced to offer a public apology and lower the ticket fees again. Decades later, Edward Williams Clay also made a satirical comic strip parodying the same nursery rhyme, 'This Is The House That Jack Built' (1840).

'This Is The House That Jack Built' (1809).

In 'The Double Humbug or the Devils Imp Praying for Peace' (1 January 1814), Napoleon gives a speech in the first panel, with the Devil at his side. In the second panel, he is no longer the "great general" and offers all his wealth and titles to the Allies, while kneeling. Apart from the two-panel sequences, the "before/after" situation is notable for using word balloons.

Rowlandson also drew many cartoons that shared a thematic connection and featured people in dialogue with one another, typically divided in two horizontal strips. Although each dialogue is intended as a stand-alone scene, he didn't use panels to separate scenes from each other. The dialogues too were simply handwritten above or beneath the characters. Examples are 'Opinions on the Divorce Bill' (2 June 1800), 'Opinions Respecting the Young Roscius' (24 December 1804), 'The News Paper' (1 October 1808), 'Wonders! Wonders!! Wonders!!!' (1 August 1809) and 'A Plan for General Reform' (29 August 1809). A special series is Rowlandson's 'Grotesque' (1799-1800), in which the characters presented within an overall theme are all depicted as small people with disproportionally large heads. It was based on an earlier series of caricatures by a friend of Rowlandson, George Murgatroyd Woodward. In addition, Rowlandson and Woodward published in The Caricature Magazine, where cartoonists like Charles Williams, Isaac Cruikshank, Piercy Roberts and others etched out his sketches. Another Rowlandson series with big-headed caricatural people talking is 'The Secret History of Crim Con' (18 August 1808).

'Reform Advised, Reform Begun, Reform Compleat' (1793).

One-panel cartoons using word balloons

Although Thomas Rowlandson drew sequential illustrated narratives with word balloons earlier in his career, he rarely combined the two again. But he did use word balloons in numerous one-panel cartoons. In 'Sir Jeffery Dunstan Presenting an Address from the Corporation of Garratt', printed on 30 December 1788, politician Jeffery Dunstan visits George III at court. In 'Neddy's Black Box', printed on 30 January 1789, writer Edmund Burke and politician Richard Brinsley Sheridan offer the Prince of Wales the head of Charles I in a treasury box. The crowd in 'The Irish Ambassadors Extraordinary, A Gallante Show' (7 March 1789) all chatter excessively in dozens of word balloons. In 'An Imperial Stride!' (12 April 1791), Rowlandson visualized the Russian-Ottoman War by depicting Czarina Catherine the Great crossing from Russia to Constantinople (present-day Istanbul) as if she was crossing a brook. Her crossing is admired by the Doge of Venice, Pope Pius VI, Charles IV of Spain, Louis XVI of France, British king George III, Prussian emperor Leopold II and Ottoman Sultan Selim III, though their dialogues all feature sexual innuendo. The cartoon 'Philosophy Run Mad or a Stupendous Monument of Human Wisdom' (29 May 1792) satirized the French Revolution as a violent tyranny. 'John Bull's Turnpike Gate' (23 April 1805), featured the British national personification John Bull refusing the pope entrance. In 'St. Valentine's Day or John Bull intercepting a Letter to his Wife' (23 February 1809), John Bull is discussing a letter with his wife.

'An Imperial Stride!' (12 April 1791). Catherine the Great crosses her Russian armies to Constantinople, while Doge of Venice, Pope Pius VI, Charles IV of Spain, Louis XVI of France, British king George III, Prussian emperor Leopold II and Ottoman Sultan Selim III gaze at her.

More erotic innuendo can be found in 'The Bishop And His Clarke, or A Peep Into Paradise' (26 February 1809), in which a bishop is beneath the sheets with Mary Anne Clarke, the mistress of Frederick, the Duke of York. That year scandal had broken out when it was revealed that she had sold army commissions, with the Duke's knowledge. She appears in two other one-panel cartoons with word balloons that same year, namely 'The Triumvirate of Gloucester Place, or the Clarke, the Soldier and the Taylor' (7 March 1809) and 'Mrs. Clarke's Farewell To Her Audience' (1 April 1809). In 'A Parliamentary Toast' (2 March 1809), parliamentarians bring a toast behind a dinner table. 'A Visit To The Synagogue' (28 April 1809), was an one-panel cartoon in which a group of men with heads shaped like food products visit a synagogue. The rabbit uses a word balloon to welcome them.

All word balloons were drawn as literal balloons. However, the one-panel cartoon 'Fancy' (20 July 1801) featured a man fancying a woman. Their dialogue simply floats above their heads.

'Six Stages Of Mending A Face', 1794.

Sequential illustrations in pantomime, or with text captions

Rowlandson made numerous sequential illustrations without dialogue. In some cases, the text caption is simply written underneath the images. 'An Essay on the Sublime and Beautiful: The Maiden Speech' (1 October 1785), was a two-part cartoon in which a cobbler is seen speaking in the first panel, while a new member of the House Commons does the same in the second panel. 'Nap in the Country, Nap in Town' (1785), used two panels to show the contrast between a couple taking a rest in the idyllic countryside and another sleeping at home on a sofa. A similar contrast cartoon was 'The New Speaker and the Wedding Night' (7 February 1789), in which a man addresses a hall in parliament, while in the second panel he prepares for his wedding night with an ugly woman, which takes a lot more courage. 'Comedy Spectators, Tragedy Spectators' (8 October 1789), contrasted ordinary people laughing at a comedy, while other, more sophisticated theatergoers weep with a tragedy. A similar cartoon was printed on 29 May 1807, albeit with a different title: 'Comedy in the Country, Tragedy in London'.

Rowlandson's 'Different Sensations' series, published on 22 October 1789, is a collection of four one-panel cartoons depicting a fat man preparing, waiting, eating and relaxing around dinnertime. All four cartoons form a thematic connection, told chronologically. 'Single and Married', printed on 1 December 1791, showed a woman yearning for a husband in the first panel, while she caresses a baby in the second. 'Modish and Prudish', released on the same day, showed the differences between a modish and a prudish woman. More female differences were addressed by Rowlandson in the etch 'St. James's and St. Giles's' (1792), where beautiful women apparently hail from the first location and ugly ones from the second. 'The Contrast' (December 1792), visualized the difference between "British Liberty" and "French Liberty". Lady Britannia is seen in the left circle and has nothing but virtues written underneath the image. Marianne is portrayed in the right circle as an old hag, with nothing but bad things underneath. The propaganda cartoon asked readers "Which is best?", in a clear attempt to condemn the French Revolution and its aftermath.

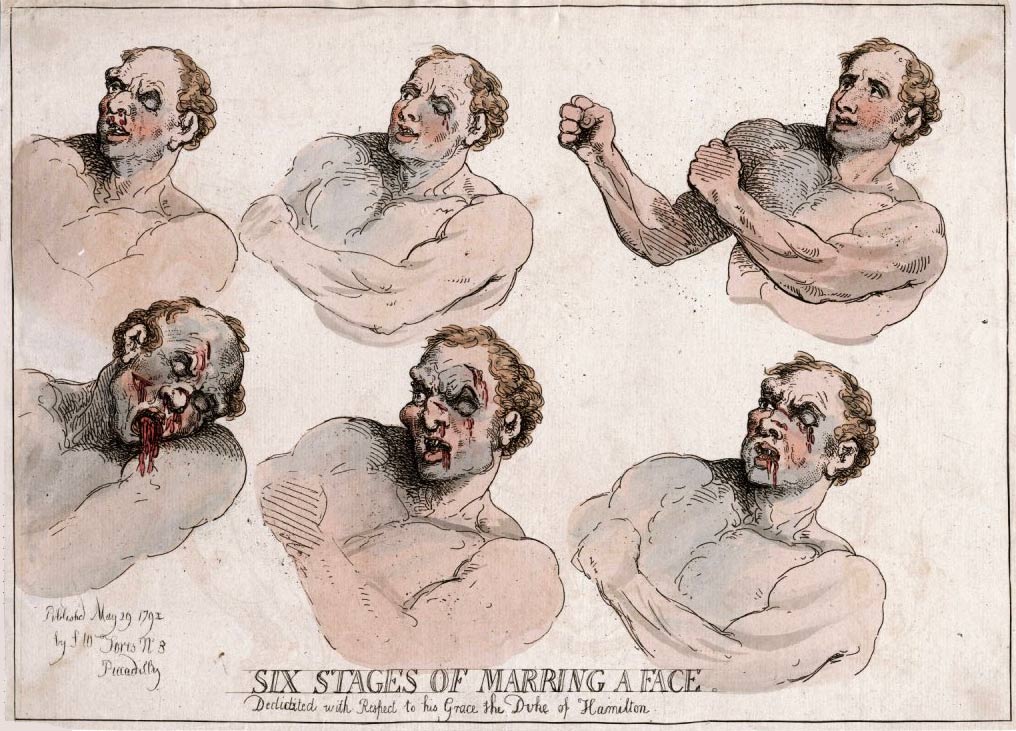

'Six Stages Of Marring A Face', 1794.

Two interesting pieces are 'Six Stages Of Mending A Face' and 'Six Stages Of Marring A Face' (both from 1794). The first work ridiculed a woman deconstructing her face with make-up and fashions in six sequences. Rowlandson proved he was an equal opportunity offender with the second cartoon, which shows a boxer's face gradually being hit into a bloody pulp. 'Salt Water and Fresh Water', printed on 25 March 1800, was a two-panel illustration which contrasts an old, plump woman taking a bath at the beach and an obese man being scrubbed in a bath tub. 'A Brace of Public Guardians' (10 July 1800), depicted a judge who fails to see that somebody is bribing a lawyer in plain sight. In the right panel, a night watchman also doesn't notice a burglary and an officer embracing a woman in a sentry box.

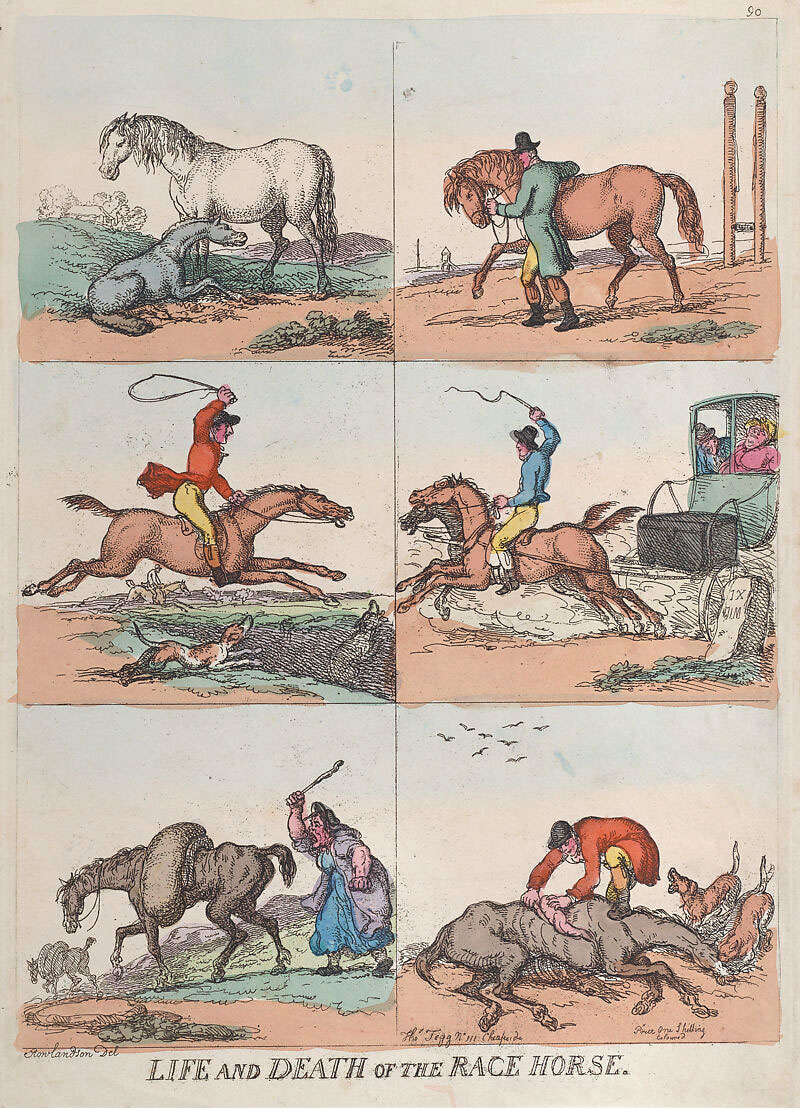

Interestingly enough, quite a number of sequentially illustrated narratives by Rowlandson featured people riding horses. Given his love for betting on horse races, this might not come as a surprise. On 1 August 1799, his 12-part cartoon series 'Horse Accomplishments' was released. Each illustration featured a person of a different profession or class trying to ride a horse, with a funny description written underneath. Rowlandson mocked the horse-riding abilities of an astronomer, paviour, whistler, devotee, arithmetician, time keeper, civilian, politician, loiterer, minuet dancer and land measurer. In 'The Puzzle for the Dog; The Puzzle for the Horse; The Puzzle for Turk, Frenchman, or Christian' all three protagonists wear a device attached to their chins. 'Life and Death of the Race Horse', printed on 25 September 1811, is a grim look at how humans use horses. In six images we see how a foal is trained to become a race horse. During the prime of its life he's an excellent animal, but when it gets too old, it is used as a pack horse. When the animal dies, it proves its final usefulness as food for a group of hounds. On 10 October 1811, Rowlandson created the text comic 'Six Classes of the Noble and Useful Animal A Horse', which depicts a race horse, war horse, shooting pony, hunter horse, gig horse and draught horse with their descriptions underneath the panels.

'Life and Death of the Race Horse' (1811).

On 12 October 1801, Rowlandson released 'John Bull in the Year 1800! John Bull in the Year 1801!' (1801). In the first panel, set in 1800, national personification John Bull is at war and sits on a chair in military uniform. In the second panel, set in 1801, peace has returned, which motivates him to play the fiddle. 'At Home and A Broad/Abroad And At Home', printed on 28 February 1807, is another two-panel cartoon. The first image shows an unhappy man at home with an ugly, obese attractive woman, or "a broad" in British slang. In the second image, the same man lies on the couch with an attractive woman, abroad in her home. 'The Captain's Account Current of Charge and Discharge' (3 February 1807), showed how an army captain goes to battle and quickly leaves again afterwards. A similar contrast sequence was 'The Huntsman Rising: The Gamester Going To Bed' (1809). The first panel portrays how a happy huntsman rises in the morning with the prospect of a good hunt. In the second panel, a gambling addict is visibly angry that he's lost so much money in one night. Yet he still decides to continue instead of quitting and going to sleep. 'Mock Turtle, Puff Taste' (20 November 1810), shows a couple licking a bowl in the first panel, while another pair are rolling dough in the second panel. Both men and women were depicted as ugly caricatures.

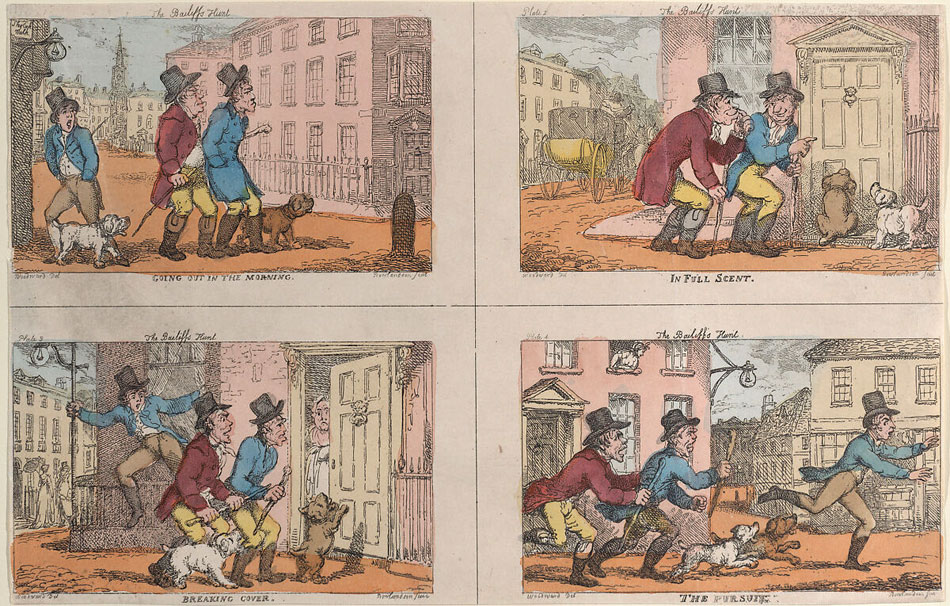

'The Bailiff's Hunt' (1809) was an interesting picture story, where a clear narrative is followed, spread over two pages. Two bailiffs spot a man jumping out of a window, but he manages to escape. Later they spot him again and bring him to justice. The story could almost be described as a pantomime comic, since all dialogue is absent, but each panel does feature a description of the situation.

In 1811, Rowlandson drew an overview of all characters from William Shakespeare's play 'Twelfth Night', with their names written above each image, and a description underneath. Presented as a series of six panels each, in four rows, it gives the drawing a veritable comic strip appearance. The two-sequential 'Glow Worms, Muck Worms' (1812) contrasted a group of happy partying people with a bunch of grumpy, bickering seniors. In the three-panel sequence 'Boney Turned Moralist' (1 May 1814), Napoleon was shown as "what he was" (a tyrant), "what I am" (a snivelling wretch) and "what I ought to be" (hung for a fool).

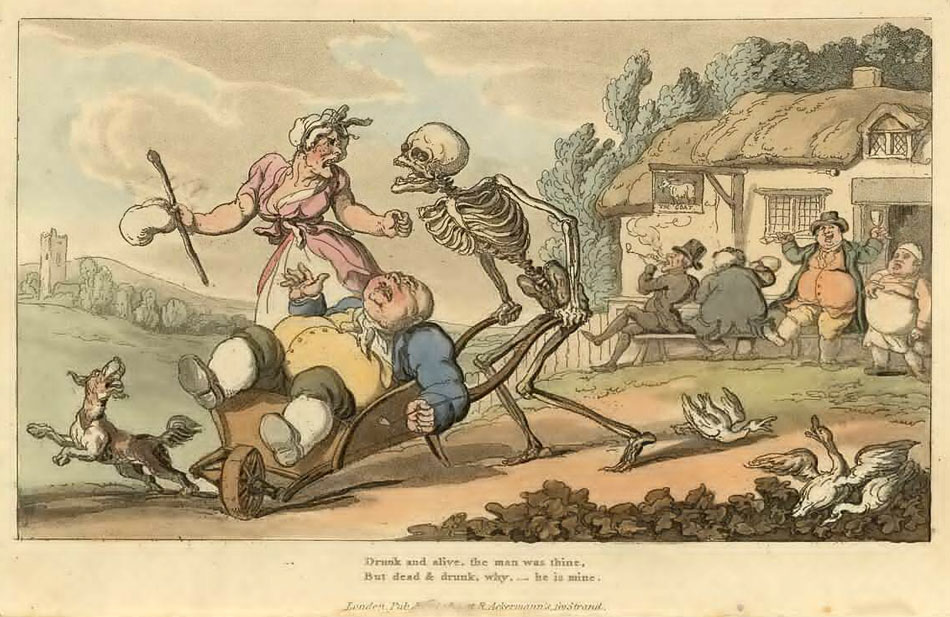

'The Sot' ('The English Dance of Death' plate 12, 1814).

Between 1814 and 1816, Rowlandson made a series of illustrations based on the 'Dance of Death' concept, namely that nobody, rich or poor, escapes the Grim Reaper. Hans Holbein the Younger had first introduced this graphic idea in 1523-1526 in a solemn and often disturbing series of thematically connected images. In Rowlandson's version, some images maintain a little of this macabreness. In one illustration, for instance, a young man bids his sweetheart goodbye as he is about to join his friends off to war, with the Grim Reaper tapping on his shoulder to hurry up. Others turn Death's arrival into a farce. He, for instance, takes an ugly woman away, much to the delight of her husband, who was apparently already having an affair with a younger woman. In another cartoon, the tables are turned. A man who boozed himself to death is carried away by the Grim Reaper in a wheelbarrow, while he argues with his annoyed wife. 'The Dance of Death' doesn't follow a chronology, but all images follow a thematic connection, with a text in rhyme printed under each image.

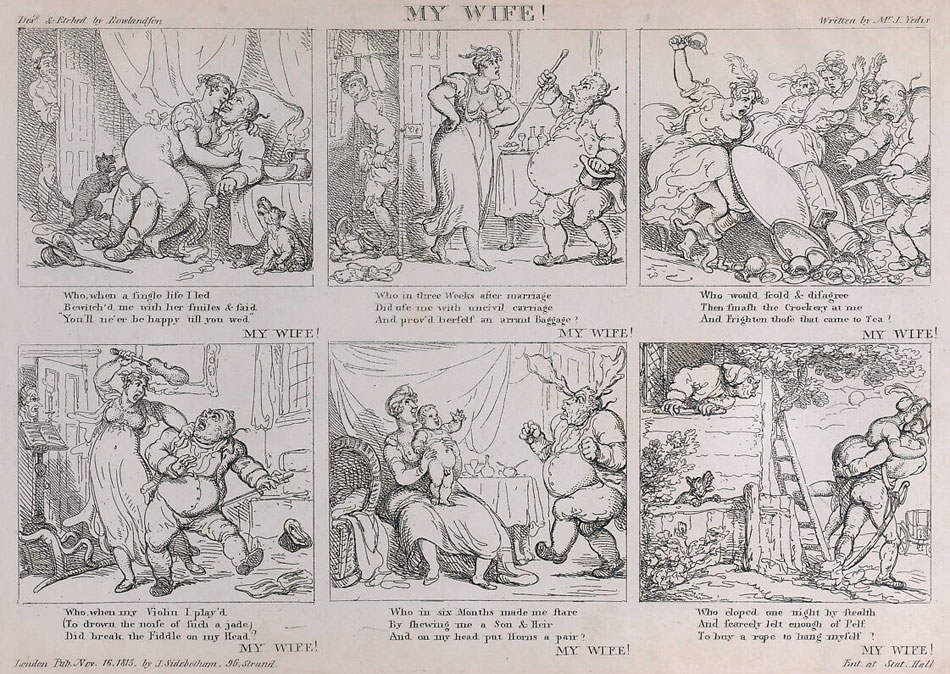

A cynical picture story driven by a clear chronology was 'The Four Seasons of Love' (15 September 1814), in which four stages of a relationship were compared with the changing of the seasons. In Spring and Summer, a couple loves each other, but in Autumn and Winter they start arguing and separate. The four-panel story has no dialogue, only season indications underneath the images. A similar unhappy relationship story was told in 'My Wife!' (16 November 1815), about a man who values his wife, but gradually discovers she's aggressive and unfaithful. The six-panel story was told with rhyming narration under each panel, summarizing the situations the man finds himself in, wondering "who is responsible." The punchline is each time: "MY WIFE!"

Book illustrations

Thomas Rowlandson was additionally active as an illustrator for novelists such as Henry Fielding, Laurence Sterne, Oliver Goldsmith and Tobias Smollett. Between 1808 and 1811, he and Augustus Pugin co-illustrated the book 'The Microcosm of London', with Pugin concentrating on the backgrounds, and Rowlandson drawing the people.

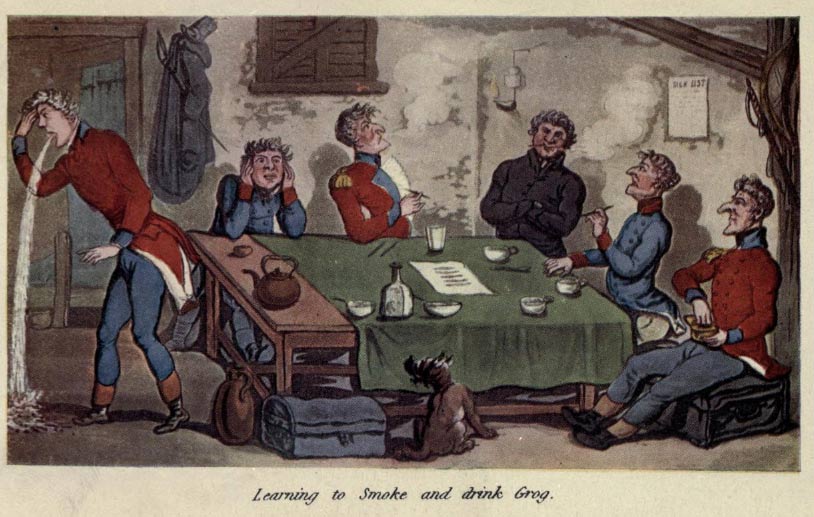

'The Military Adventures of Johnny Newcome', with an account of his campaign on the Peninsula and in Pall Mall and notes, by an officer.

Dr. Syntax

Of all the books Rowlandson livened up with his drawings, three novels in particular are interesting for comic historians: William Combe's 'The Tour of Dr. Syntax in Search of the Picturesque' (1812), David Roberts' 'The Military Adventures of Johnny Newcome, With an Account of his Campaign on the Peninsula and in Pall Mall and Notes, by an Officer' (1815) and John Mitford's 'The Adventures of Johnny Newcome in the Navy' (1818). All three follow one central character throughout a series of humorous events, presented in sequences. Even so, text and images are still separate entities. One has to read the books to understand what is going on in the illustrations. Even the descriptions underneath consist of just one sentence.

'The Tour of Dr. Syntax in Search of the Picturesque'.

And yet particularly 'Dr. Syntax' is important because Rowlandson used this character again in two literary sequels, which he illustrated too: 'Dr. Syntax in Search of Consolation' (1820) and 'Third Tour of Dr. Syntax in Search of a Wife' (1821). This makes the character the earliest known example of a prototypical picture story protagonist, comparable to a comic hero. Syntax was also the first "comic character" to be the subject of merchandising. A century earlier, William Hogarth's picture story 'A Harlot's Progress' (1731) had led to similar spin-off adaptations, like plays, operas, pamphlets and poems. But Rowlandson's 'Dr. Syntax' was not merely adapted. The character was portrayed on hats, coats, mugs, puppets, tops, crockery and wigs, while also being the first prototypical comic book character translated into other languages (Danish, German, French). Last but not least, Dr. Syntax was an important influence on the first actual comic artist in history, Rodolphe Töpffer.

Erotic art

Curiously enough for a cartoonist so associated with crude, repulsive caricatures, Rowlandson was also a prolific provider of erotic illustrations. Since pornography was still illegal in the late 18th century and early 19th century, many erotic drawings were sold under the counter. Given the sheer amount of erotic material Rowlandson drew, the demand and pay were presumably lucrative. Some, however, were just drawn, inked and put in water color, without being engraved or even published. An example is 'The Old Harlot's Dream', which depicted an old prostitute dreaming of sex and gigantic phalluses.

'The Empress of Russia receiving her Brave Guards' (1810s). Elizabeth Alexeievna, wife of Czar Alexander I, has sex with her guards.

Many of Rowlandson's erotic drawings fall in the farcical category, depicting sailors, adulterers, sultans inspecting their harem, perverts taking advantage of unsuspecting damsels, voyeurs observing copulating couples or simply people surrounded by phallic symbols. Many are ugly, lewd middle-aged or old geezers, or despicable wrinkled hags. He didn't even shy away from depicting heads of state in the sexual act, like in his 1810s cartoon 'The Empress of Russia receiving her Brave Guards', where empress Elizabeth Alexeievna is gangbanged by her guards (some sources have incorrectly identified this empress as Catherine the Great). In some cases, modern-day audiences might be bewildered that some of the erotic situations in Rowlandson's drawings were based on real-life phenomena. In 'The Exhibition Stare Case, Somerset House' (1800), the reader first assumes Rowlandson misspelled the word "stair case", only to realize it is a clever pun on the fact that some visitors at exhibitions loved to peer at ladies descending or ascending the stairs, just to get a glimpse of their legs and - on a good day - undergarments. In The World, Fashionable Advertiser (8 May 1787), a journalist wrote: "(...) Exhibitions are now the rage and though some may have more merit, yet certainly none has so much attraction as that at Somerset House; for, besides the exhibition of pictures living and inanimate, there is the raree-show [peep show] of neat ankles up the stair-case which is not less inviting…" In Rowlandson's cartoon, the perverts squeal in delight, since all the women trip and tumble from the stairs, revealing their lack of underpants.

'The Exhibition Stare Case, Somerset House' (1800).

Other erotic drawings by Rowlandson were genuinely titillating images with attractive-looking people, drawn in a more realistic style. Most were very explicit and would be classified as pornography today. In 1845, 18 years after Rowlandson's death, several of his erotic illustrations were brought together posthumously in the book 'Pretty Little Games for Young Ladies & Gentlemen, with Pictures of Good Old English Sports and Pastimes', accompanied by bawdy rhymes under each image. 'Pretty Little Games' was much sought after and so frequently reprinted.

King George IV collected erotic cartoons by Rowlandson and even ordered specific ones for private possession. His successor, Queen Victoria, hated them and had them destroyed during her reign. She wrote: "The many very improper and indecent prints entirely collected - there were quantities of the most obscene character - by George IV." Reportedly, some may still be in the Royal Collection, though not that many. From the late 19th century until late in the 20th, Rowlandson's erotic cartoons were kept out of the public eye. It wasn't until the post-World War II sexual revolution that a compilation book was published, 'The Forbidden Erotica of Thomas Rowlandson' (The Hogarth Guild, 1970), with an introduction by Kurt von Meier.

'Doctor Convex and Lady Concave'.

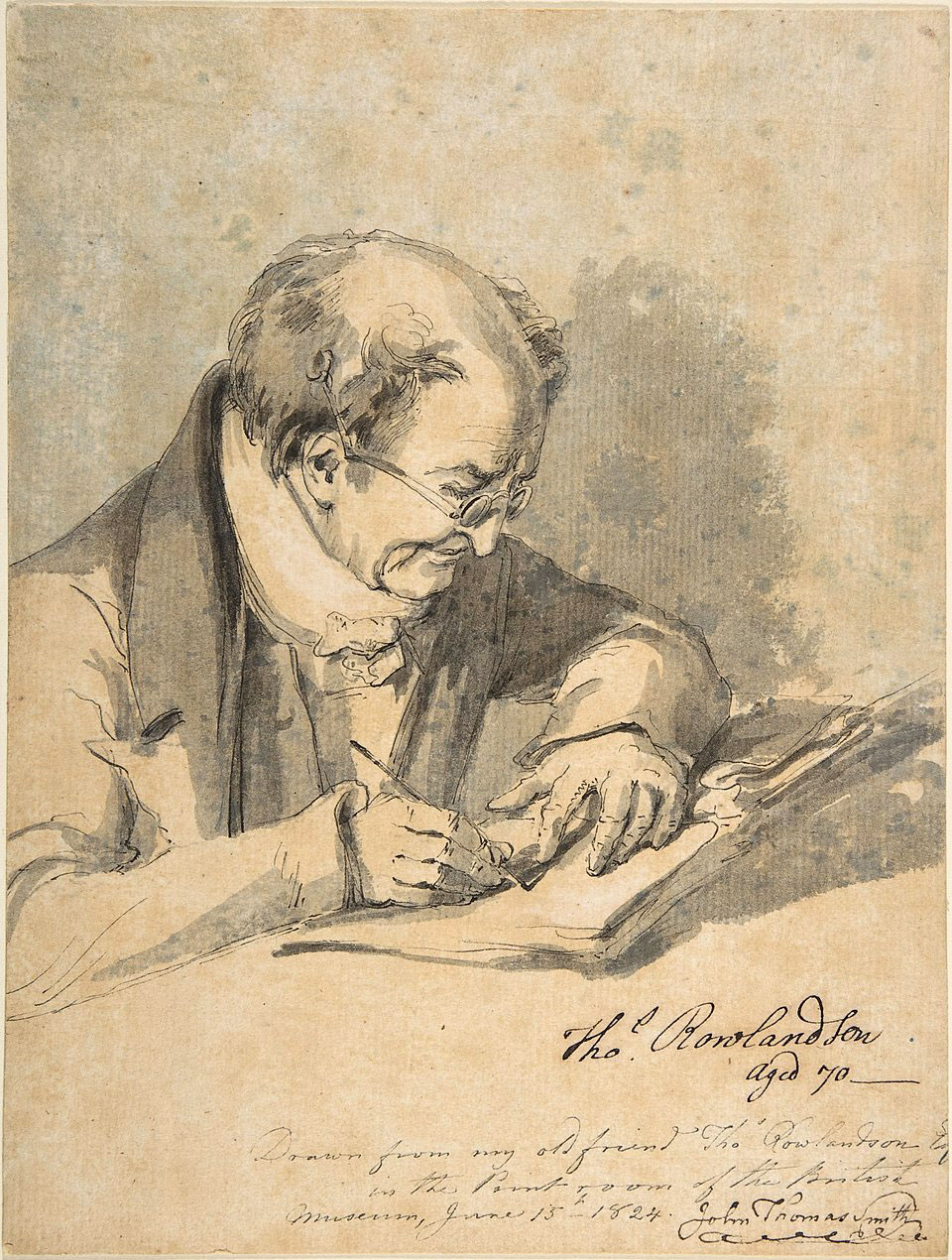

Death, legacy and influence

Thomas Rowlandson died in 1827 after an illness, at age 70. But his legacy as one of England's greatest cartoonists endures. His crass and grotesque drawings all seemed to be a summarization of the caption he wrote under his 1802 cartoon 'Doctor Convex and Lady Concave', which went: "Man is the only creature endowed with the power of laughter, is he not also the only one that deserves to be laughed at?"

In his home country, Thomas Rowlandson was an influence on artists like Roger Law, Roy Raymonde and Ronald Searle. Interviewed for Cartoonist Profiles issue #4 (November 1969), Searle praised Rowlandson for his "wit, genius, ability to handle line, ability to range from the broadest and most clownish grotesque to a cunning subversive charm." He additionally inspired artists in The Netherlands (Oscar de Wit), Sweden (Johan Tobias Sergel), Switzerland (Rodolphe Töpffer) and the United States (Edward Williams Clay, Arnold Roth, Edward Sorel).

Thomas Rowlandson at age 70, portrayed by John Thomas Smith.