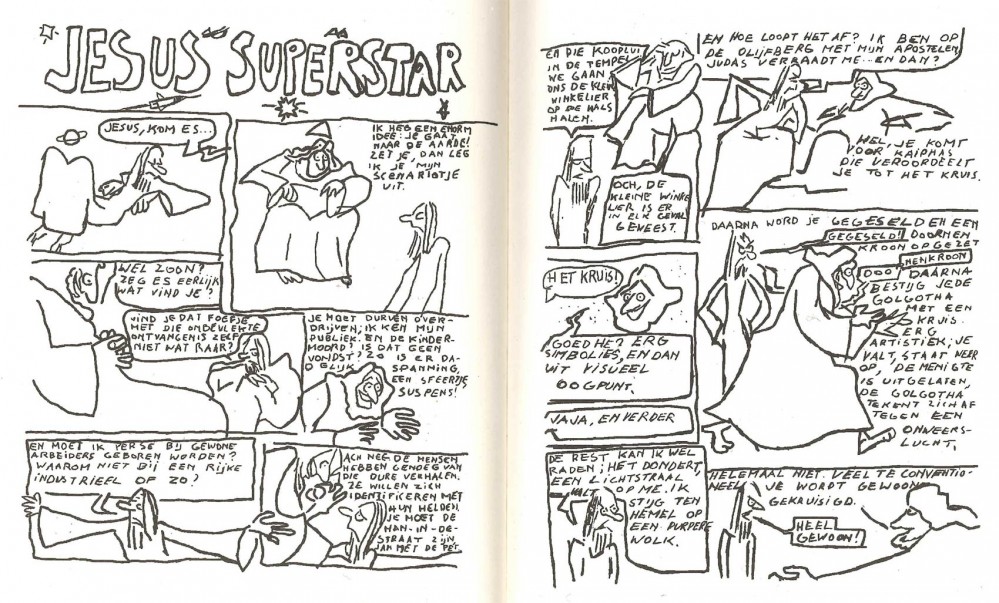

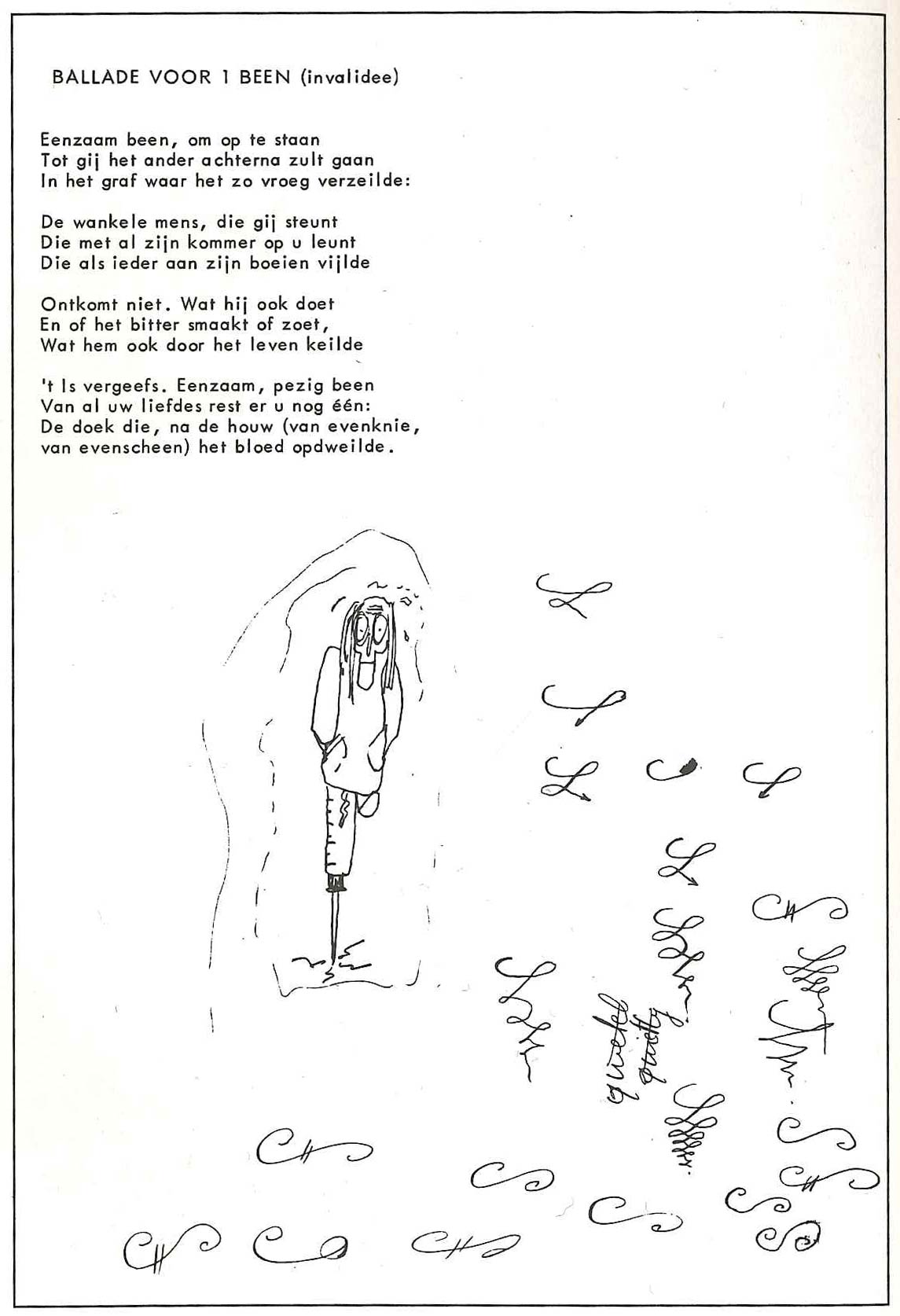

The first and second page of 'Jesus Superstar', 1974.

Jotie T'Hooft was a Belgian hippie poet who enjoys a cult status in Flanders. He became famous in the early 1970s with his poems and essays about rock 'n' roll, drugs and death. A troubled soul, T'Hooft battled with drug addiction and suicidal tendencies. At age 21, he took a fatal overdose. Little known is that he also published a comic strip, 'Jesus Superstar' (1974). A few months before his death, he additionally wrote a funny essay about drug use among classic comic characters.

Early life

Johan T'Hooft, nicknamed "Jotie", was born in 1956 in Oudenaarde. His father was a teacher and librarian. When T'Hooft hit puberty, he became rebellious. Like all teenagers, he started to question society. He became interested in Communism and found solace in the novels and poetry of Hermann Hesse and Franz Kafka, as well as underground comix by Robert Crumb. He enjoyed psychedelic rock bands like The Doors, The Grateful Dead, The Velvet Underground and alternative artists like Lou Reed, David Bowie and Frank Zappa. These helped him escape the boredom of his everyday life. At age 14, T'Hooft took his first LSD trip, which led to heavier stuff like cocaine, amphetamines and heroin. His school grades went down and he was kicked out of high school. When no other school wanted to take him in, he tried out various jobs, including waiter, night watchman, cook, furniture restorer, chimney sweep and gas station attendant. He briefly tried to study art at the Ghent Academy, but soon dropped out again.

The college dropout tried to survive by dealing drugs. Together with a junkie friend named Chapo, they spent their days with sex, drugs, rock 'n' roll and poetry. One day in 1973, Chapo's parents took their son away to put him back on the "good path". This depressed T'Hooft so much that he attempted suicide, but failed. Jotie's parents realized they had to do something and brought him back home.

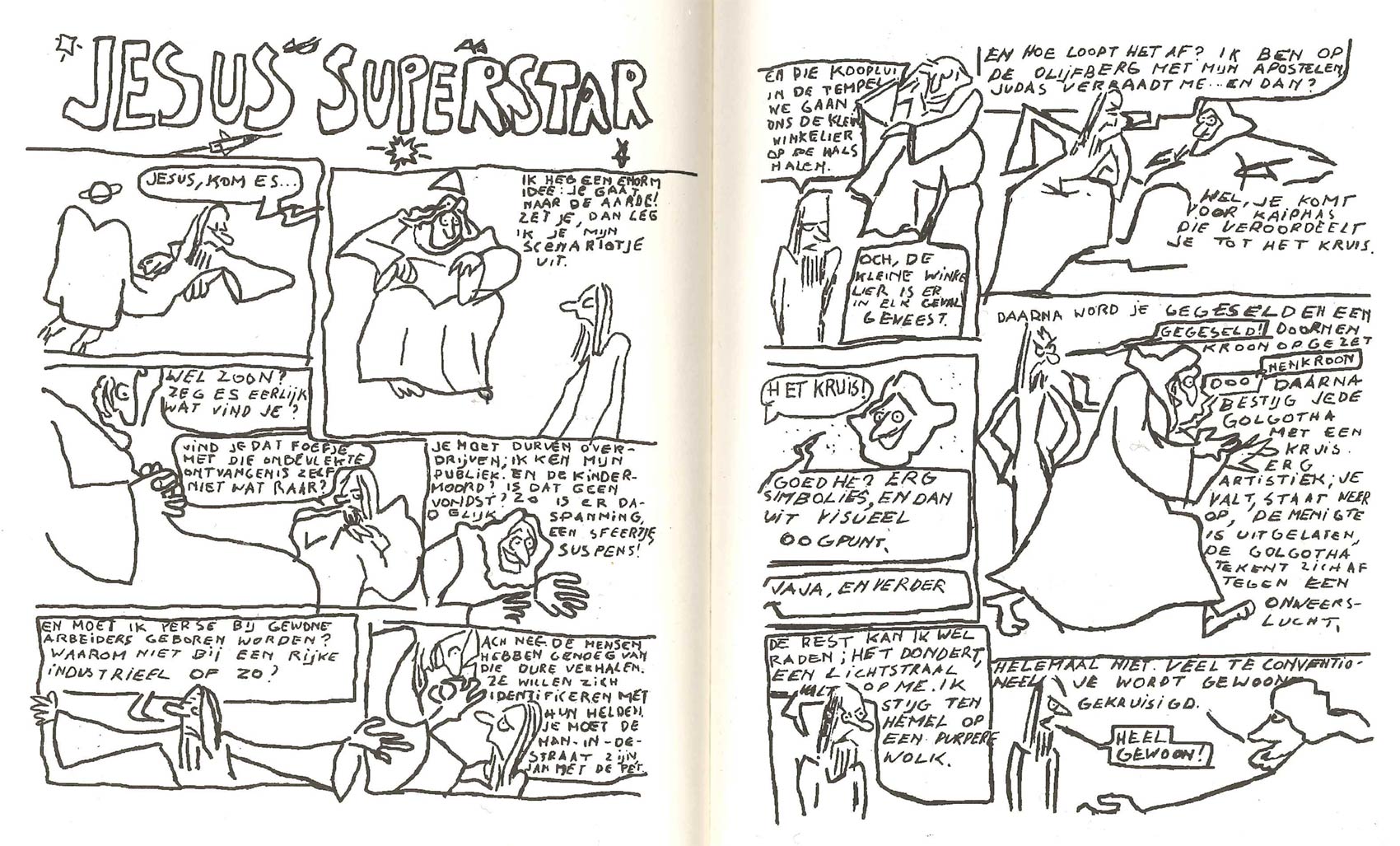

Third page of 'Jesus, Superstar', 1975.

Early publications

Spending his days in his parents' house, T'Hooft continued his drug-induced life and wrote several pages of poetry and essays. The majority dealt with typical teenage angst, such as the search for meaning, love, sex and refusal to be integrated in society. He was morbidly fascinated with death and constantly flirted with ending it all. Among his more enjoyable writings were various articles, reviews and homages about his favorite rock artists, concerts and records. They were published in local magazines like Kentering, DW&B, De Vlaamse Gids, NVT, Yang, Kreatief, Amarant, Bok, Gedicht, 't Liedboek, Het Weekblad der Vlaamse Ardennen, Stop and Schuim.

Comics

In November 1974, T'Hooft drew a three-page comic strip, 'Jesus Superstar', in which God talks with Jesus. After the Heavenly Father tells His Son that he ought to be tortured and crucified, Jesus naturally feels nothing for this plan. God keeps insisting and eventually promises he'll save Jesus, which convinces the Messiah to go through with the plan. In the final panel Jesus gets skeptical again and asks: "You're not going to abandon me, are you?", to which God replies: "Come on, trust me: your own father." The blasphemous comic was published in an issue of the Bokkrant and had T'Hooft's friend N. as co-author.

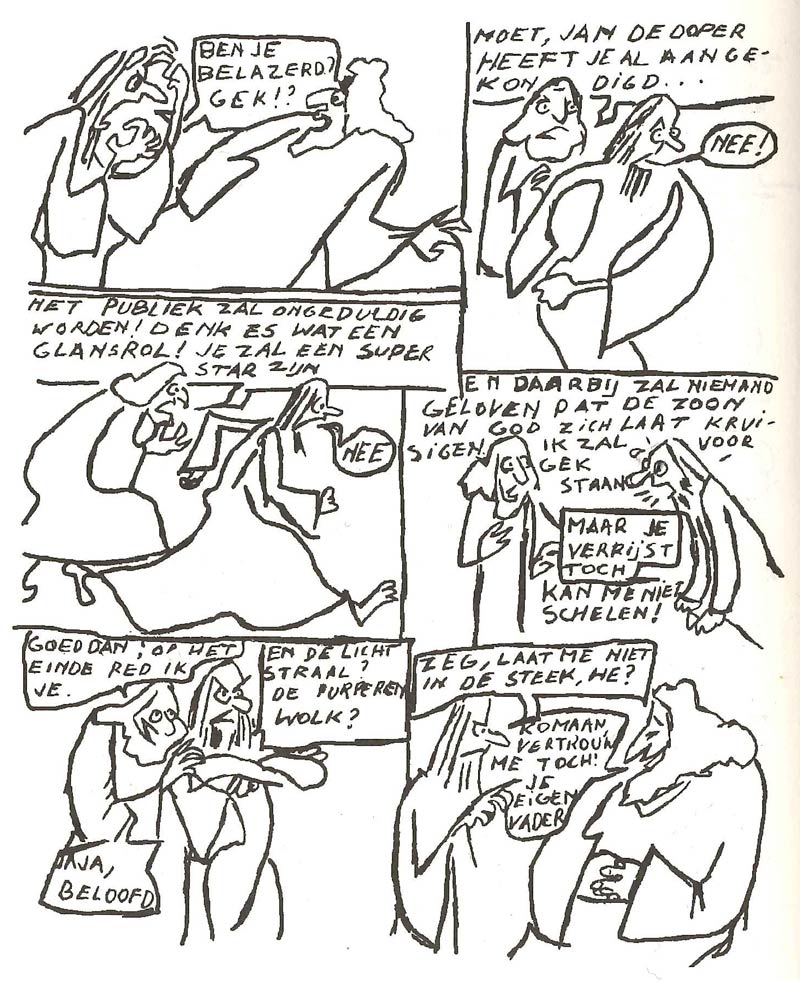

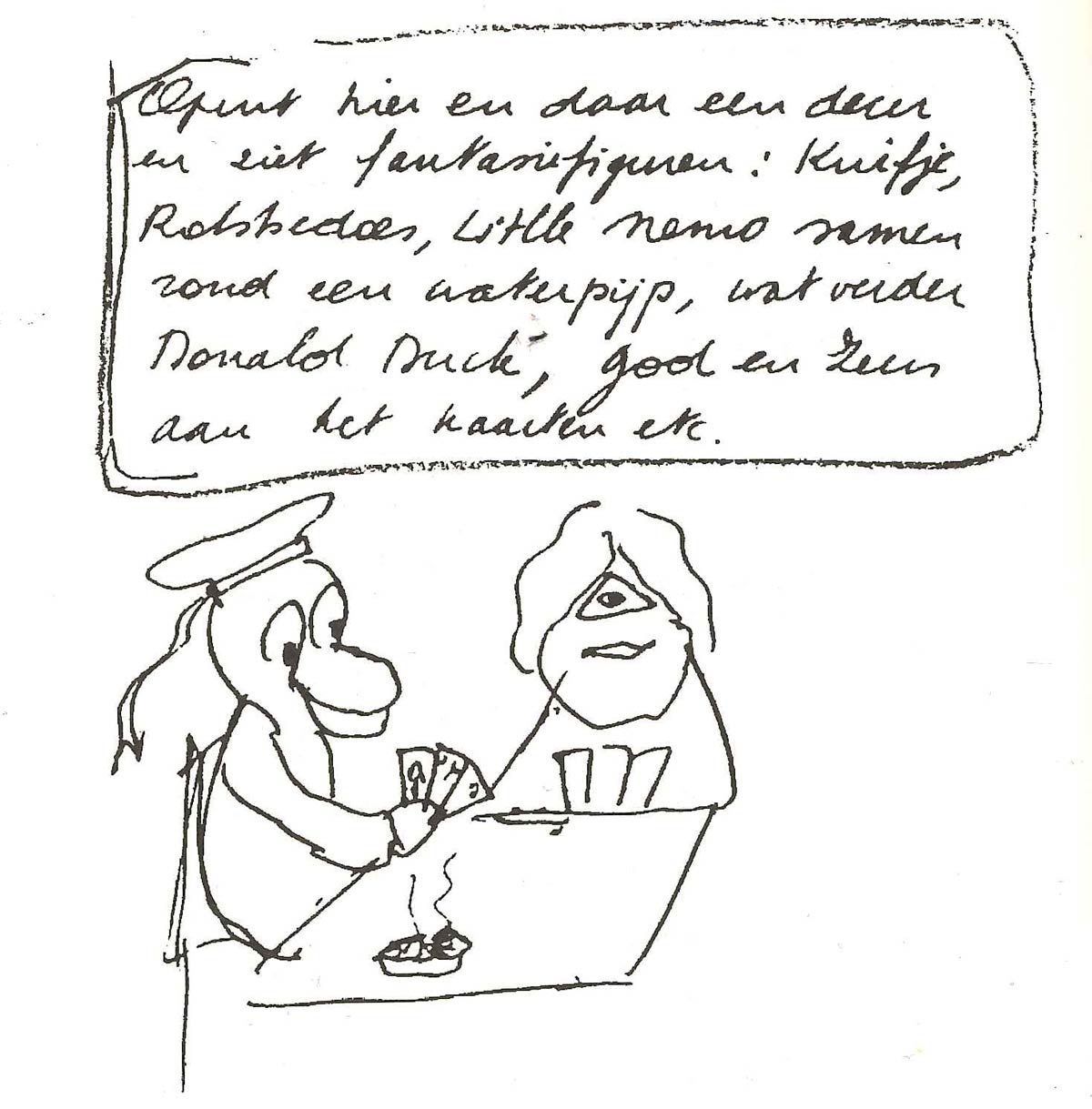

Jotie also wrote a storyboard for an animated film, which was never produced. The story features cameo appearances by Tintin, Spirou, Little Nemo and Donald Duck. A friend of Jotie, Sjors, also wrote him a letter illustrated with comic strip panels, dated 29 April 1976. All these unpublished comics were made public in the book 'Een Pijl in het Niet. Een Leven in Teksten' (Houtekiet, 1997).

Illustration by T'Hooft in a letter to one of his friends. Translation: "Here and there he opens a door and sees fantasy characters: Tintin, Spirou, Little Nemo together around a hookah pipe, a little further Donald Duck, God and Zeus playing cards, etc."

Drug use in comics

In 1977, T'Hooft wrote 'Het Gebruik van Verdovende Middelen Bij Traditionele Stripfiguren', a funny essay defending drug use by pointing out that various characters from so-called "clean and innocent" comics are actually junkies themselves. As he wrote: "Reading Hergé's 'The Blue Lotus' at age ten, where Tintin resides in a luxuriant opium den, clumsily disguised with the fund glasses that would become so popular with other users, and sucking on an opium pipe with closed eyes, contributed much to the destruction of my youth." He then pointed out that the Count of Champignac in André Franquin's 'Spirou' stories is an enthusiastic mushroom cultivator and uses several of his extracts on Fantasio, who immediately gains tremendous physical powers. In other albums of the series, several of the Count's injections and potions have similar effects. T'Hooft also reminds readers that Marc Sleen's Nero swallows opium pralines in 'De Groene Chinees', smokes opium cigars in 'De Spekschieter' and the title of 'Het Zevende Spuitje' ('The Seventh Injection') "probably says enough".

His watchful eye also noticed that Lambik uses opium in Willy Vandersteen's 'De Witte Uil', that Fantasio takes tranquillizers in 'Bravo les Brothers' and alcoholic Captain Haddock hallucinates in 'The Crab with the Golden Claws'. Nero eats a peach which makes him swing vines in 'De Krabbekokers', while becoming a football legend after eating a brew with hair in 'De Witte Parel'. His son Adhemar drinks beer in 'De Zoon van Nero', before becoming a scientist, while in 'Les Ressucités' Will and Tillieux's 'Tif et Tondu' take peyote and Tillieux' Inspecteur Crouton smokes opium cigars in the 'Gil Jourdan' album 'Le Chinois à Deux Roues'. T'Hooft briefly mentions the frequent opium smuggling in 'Tintin', Haddock and Madam Pheip's tobacco use and René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo's Obelix' obsession with magic potion. He concludes his essay with the remark: "Comics are far more honest and open about drugs than newspapers. Is this because they are more grounded in fantasy? What makes these characters living in a fantasy world with little boundaries still long for a transcendental experience?"

Downward spiral, death and legacy

In 1974, on his 18th birthday, T'Hooft was arrested for drug possession and dealing. He spent seven weeks in the correction center of Ruiselede under heavy psychiatric observation. After his release, he returned to Ghent, where he soon got addicted again. He met a girl there whom he married in secret. The marriage had two advantages. First of all: the juvenile court could no longer touch him. Secondly, the girl's father, Julien Weverbergh, was head of publishing company Manteau. Thanks to him, T'Hooft got a job as lecturer and was able to publish two poetry collections: 'Schreeuwlandschap' (1975) and 'Junkieverdriet' (1976). The latter won the Reina Prinsen Geerligsprijs.

While it brought him literary fame and respect, his addictions remained problematic. Soon the young couple found themselves in serious debt. T'Hooft tried to use a cheque from Manteau without their knowledge, but was caught. It motivated him to another failed suicide attempt. His wife eventually left him, also because he often became violent while under the influence. T'Hooft's downward spiral now took a nosedive. In the fall of 1977, the isolated poet wrote "Dag kleine meid! Veel geluk!" ("Bye, little girl! Good luck to you!") on the wall of his bedroom. He put the song 'The End' by The Doors on his record player and stuck the needle on endless repeat. Afterwards, he took a cocaine overdose. His suicide at the tender age of 21 increased his readership and guaranteed public attention, which continues to this very day.