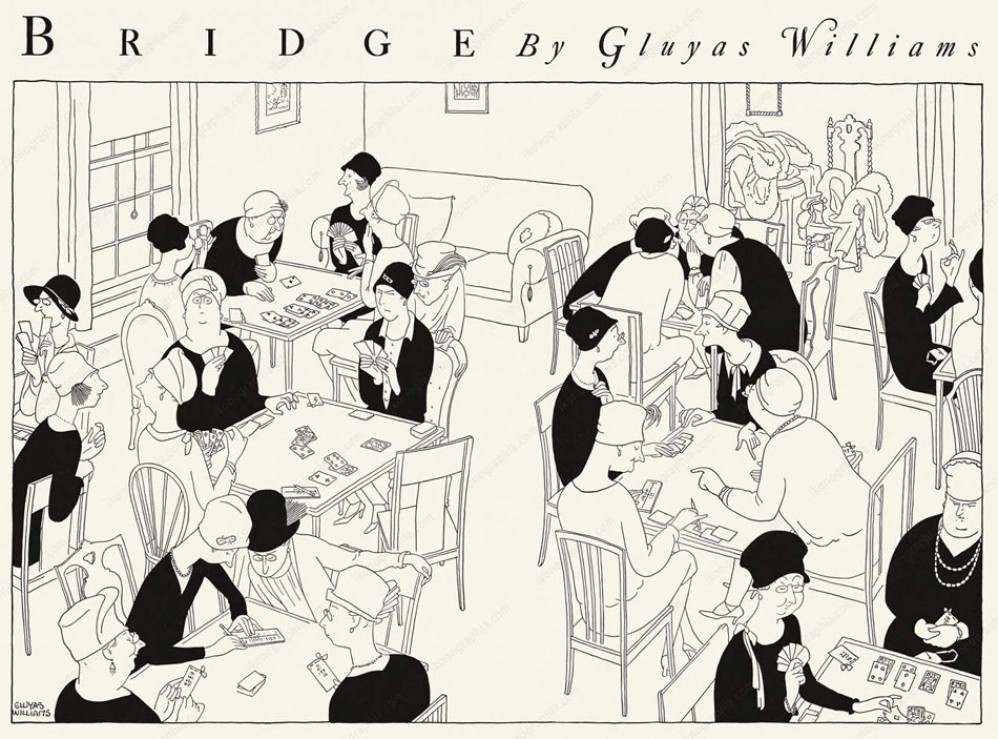

'Bridge' (Cosmopolitan #6, 1928).

Gluyas Williams was an early to mid-20th century U.S. gag cartoonist, remembered for his witty observational comedy. From the 1920s until the early 1950s, his drawings were widely syndicated in many newspapers and magazines, most famously The New Yorker. Williams combined elegant linework with gentle slice-of-life humor. His feature never had one single permanent title, but recognizable human behavior was always the common theme. Williams was additionally notable as illustrator of Robert Benchley's humorous columns in Vanity Fair magazine.

Early life

Gluyas Williams was born in 1888 in San Francisco, California, as the youngest of eight children of hydraulic engineer Robert Neil Williams and Virginia Gluyas. His first name (of which the first syllable should be pronounced as "glue") is Cornish and his mother's maiden name. Williams' older sister Kate Carew (1869-1961) later became a well-known caricaturist, illustrator and comic artist in her own right. Due to his profession, Williams' father was often working abroad, for instance in Chile, and so rarely at home. Between 1892 and 1901, Williams' mother took her children on a long trip to Europe, using 30,000 dollars she won with a lottery ticket.

Gluyas Williams studied Law at Harvard College in Cambridge, Massachusetts, while publishing illustrations in the Harvard Lampoon and serving as the paper's art editor. A notable Lampoon mate was future humor columnist Robert Benchley, who aspired to become a cartoonist at the time. According to Benchley, Williams advised him to stick to writing, as his drawings weren't very good. Yet Williams denied having ever said this. Either way, both men later had successful careers, with Williams illustrating Benchley's columns. Another college friend was John Reed, later famous for his journalistic report 'Ten Days That Shook the World'.

In 1910-1911, Williams spent six months in Paris to work in the studio of Angelo Colarossi, studying life drawing at the Académie Colarossi. Lack of money forced him to return to his home country again, where he completed his law studies and graduated. Still, he decided to follow his sister's example and chose for a career in newspaper and magazine cartooning. His main graphic influences were Aubrey Beardsley, H.M. Bateman and Caran d'Ache, while he also expressed admiration for comic artists E.C. Segar and Frank Willard. In the 1940s, Williams moved to Boston, Massachusetts, later settling in Newton in the same state.

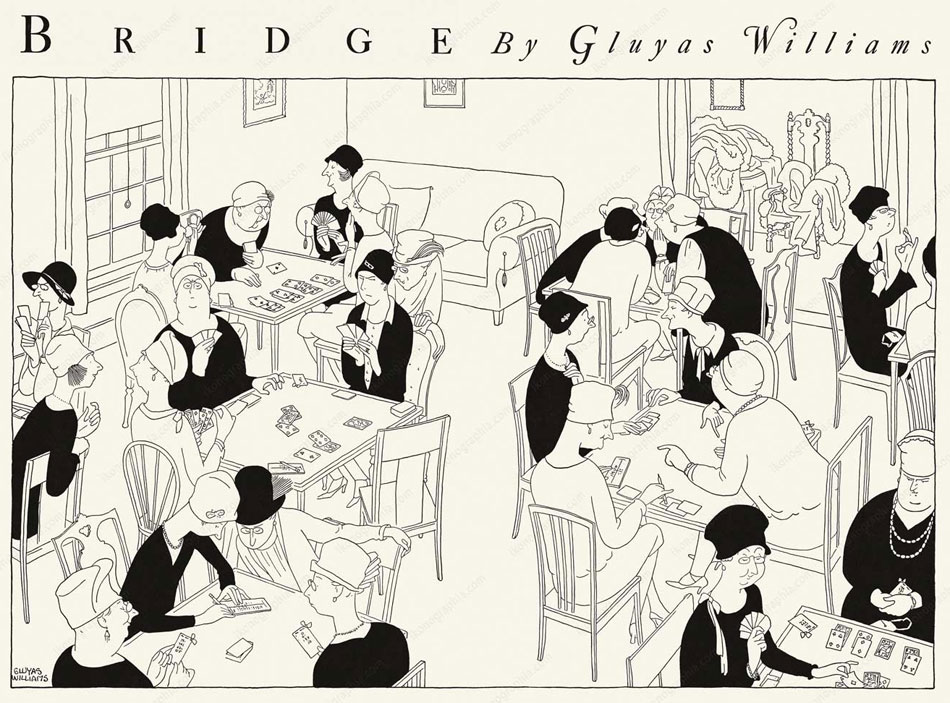

'An Idyl Of Occupied France' (Collier's, 13 April 1918), ridiculing German emperor Wilhelm II.

Cartooning career

Williams drew his first daily comic strip for the Boston Journal right before the First World War broke out. Titleless, it ran for three months during the summer period and looking back on it, the artist described it as "terrible". Between 1910 and 1920, Williams worked as head of The Youth Companion's art department. During this period, he started freelancing cartoons to other magazines, like Century, Collier's and Life. In the latter magazine, he drew the political satire 'Senator Sounder'. For the Boston Evening Transcript, he made theatrical caricatures and, briefly, political caricatures for the William Randolph Hearst papers. Many of Williams' cartoons from the 1917-1918 period ridiculed the German emperor Wilhelm II and general Paul Von Hindenburg. Originally, his cartoons were syndicated by Wheeler, but from 1924 on, the Bell Syndicate carried them for the rest of his career. Throughout the 1920s until the early 1950s, Williams was also house cartoonist for the newspapers The Boston Globe and The Plain Dealer.

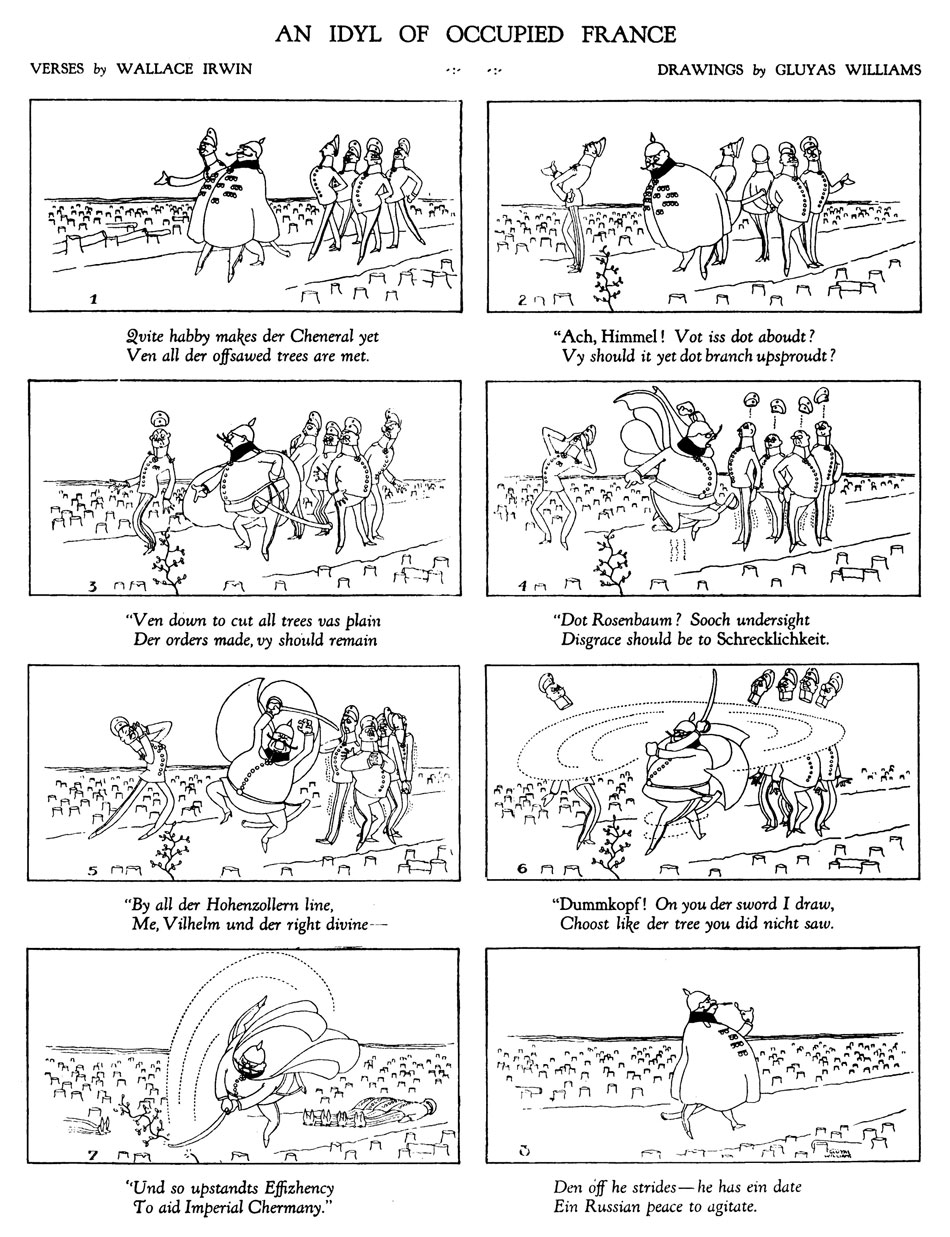

'Industrial Crises' (from The New Yorker).

Style

Gluyas Williams is notable for his gracious graphic style. His characters are elegantly rendered, with round shapes and expressive poses. The linework is minimalist, stripping everything down to its essence. Williams was a master in observational comedy. All of his cartoons and comics focus on people caught up in their own little problems, annoyances or distractions. He presented their all-too-recognizable laughable struggles in different formats, and under different titles. Some are one-panel cartoons, accompanied by a lengthy description underneath. 'Difficult Decisions', for instance, portrays characters in a dilemma or a catch-22 situation. This could range from a father arriving back with rapidly melting ice cream cones only to find out his family is temporarily gone for the moment, or a little boy wanting to see whether daddy really tripped over his toy truck, while simultaneously pondering whether it might be wiser to stay in his room for a while. 'The Minute That Seems A Year' centers on short, awkward or tense moments. Examples might be a dead silence during a conversation that isn't going anywhere, or a dropped coin rolling dangerously close to a manhole. The rather bluntly titled 'The World At Its Worst' (published in The Boston Globe from 13 September 1922 on) visualizes moments when one is glad not to stand in the shoes of Williams' characters. They range from a husband anticipating that his wife will suggest redecorating the living room, to a woman rushing to catch a streetcar, only to find out it's the wrong one. 'Raconteurs', published in The New Yorker, focuses on people who keep chattering when others wish they would shut up. 'Hello, Hello', published in The Boston Globe from 2 October 1922 on, pokes fun at conversations not going according to plan.

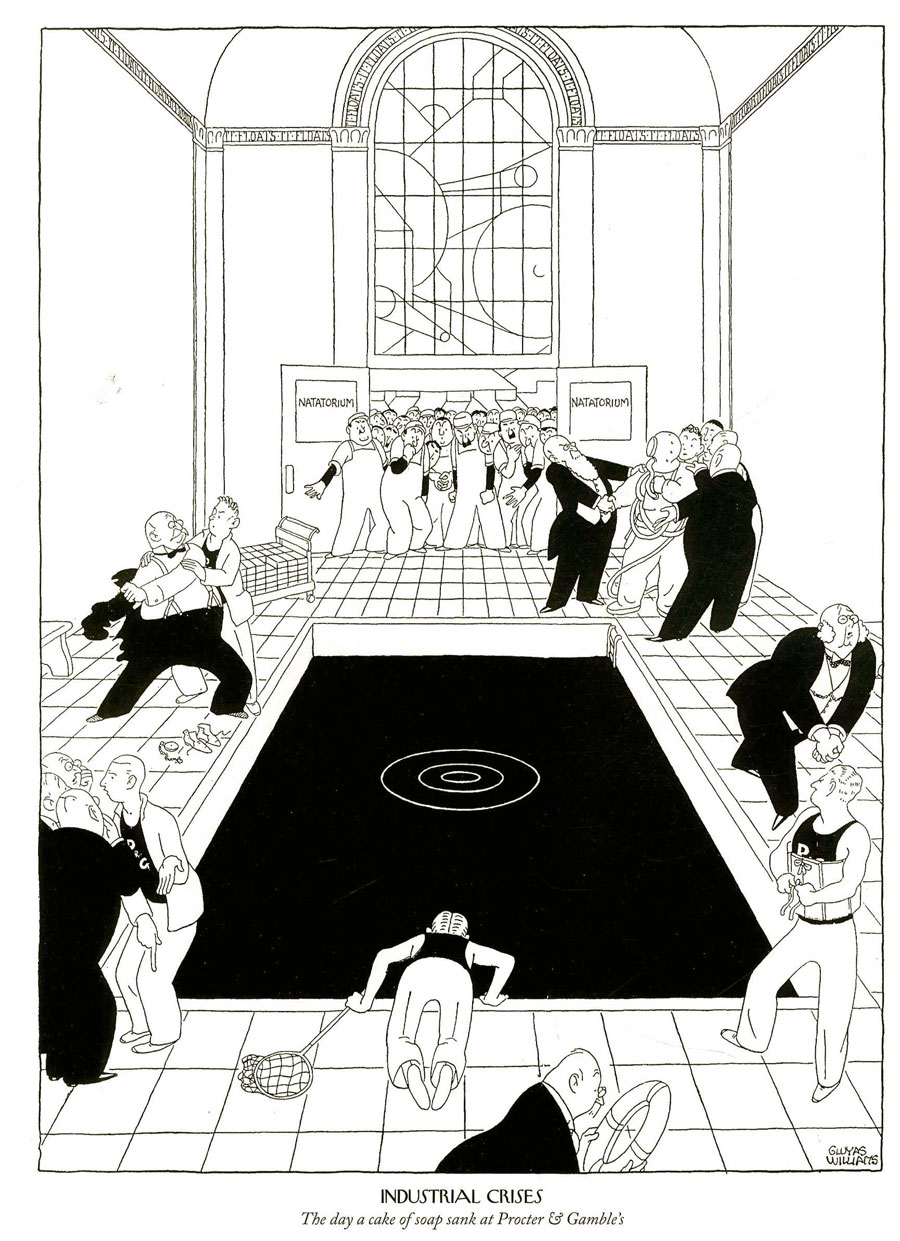

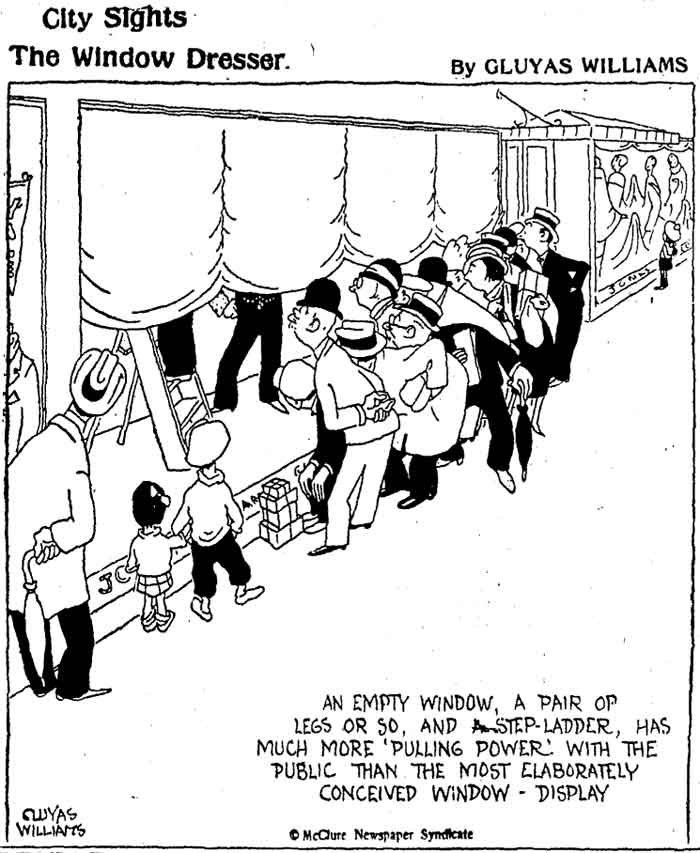

'City Sights' (15 September 1925).

Some of Williams' observational one-panel cartoons are set in specific locations. 'Suburban Heights' (published in The Boston Globe starting on 19 September 1922) focuses on people in towns and villages, while the urban variant is titled 'City Sights'. The comedy varies from curious passersby stopping to stare at a half-opened shop window, to a more poetic scene of a lonely policeman patrolling the streets at night. In The New Yorker, 'Industrial Crises' brings the reader to the highest echelons of society, featuring Williams at his most absurd, with stuffy businessmen in suits panicking over extraordinary trivial matters. A classic example is his cartoon depicting employees of Heinz 57 steak sauce frantically recounting their stock, because they have produced 58 varieties instead of the usual 57. 'Industrial Crises' is also a rare showcase for Williams' caricaturing. In some cartoons, the crisis is set in the White House, where president Herbert Hoover refuses to leave until his other rubber shoe is found, or in the Oval Office, where president Franklin D. Roosevelt is cornered by dozens of curious journalists. 'Bedtime Stories', (published in The Boston Globe from 24 October 1922 on) is set in people's bedrooms.

In weekly and monthly magazines, Williams could make his one-panel cartoons larger and more detailed. In Cosmopolitan, his feature 'Ourselves as Others See Us' depicts people in restaurants, waiting halls and sports tribunes. Instead of one comical situation, the attentive reader is treated to several at once. The large panoramic shots show dozens of people caught up in witty behavior. Each man, woman, child or animal is individualized. Williams had a good eye for composition. He balanced the crowds out by including "less busy" spaces or contrasting people in black or grey costumes along the ones dressed in white. His crowd drawings are all the more impressive, since he never used white-out to correct his lines, being under the mistaken impression that his idol Aubrey Beardsley never did so either.

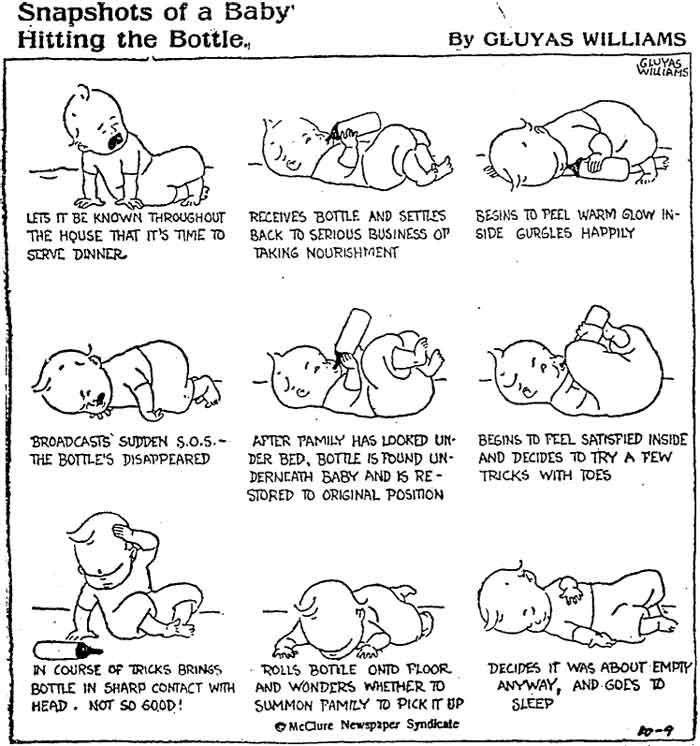

'Snapshots Of A Baby Hitting The Bottle' (9 October 1925).

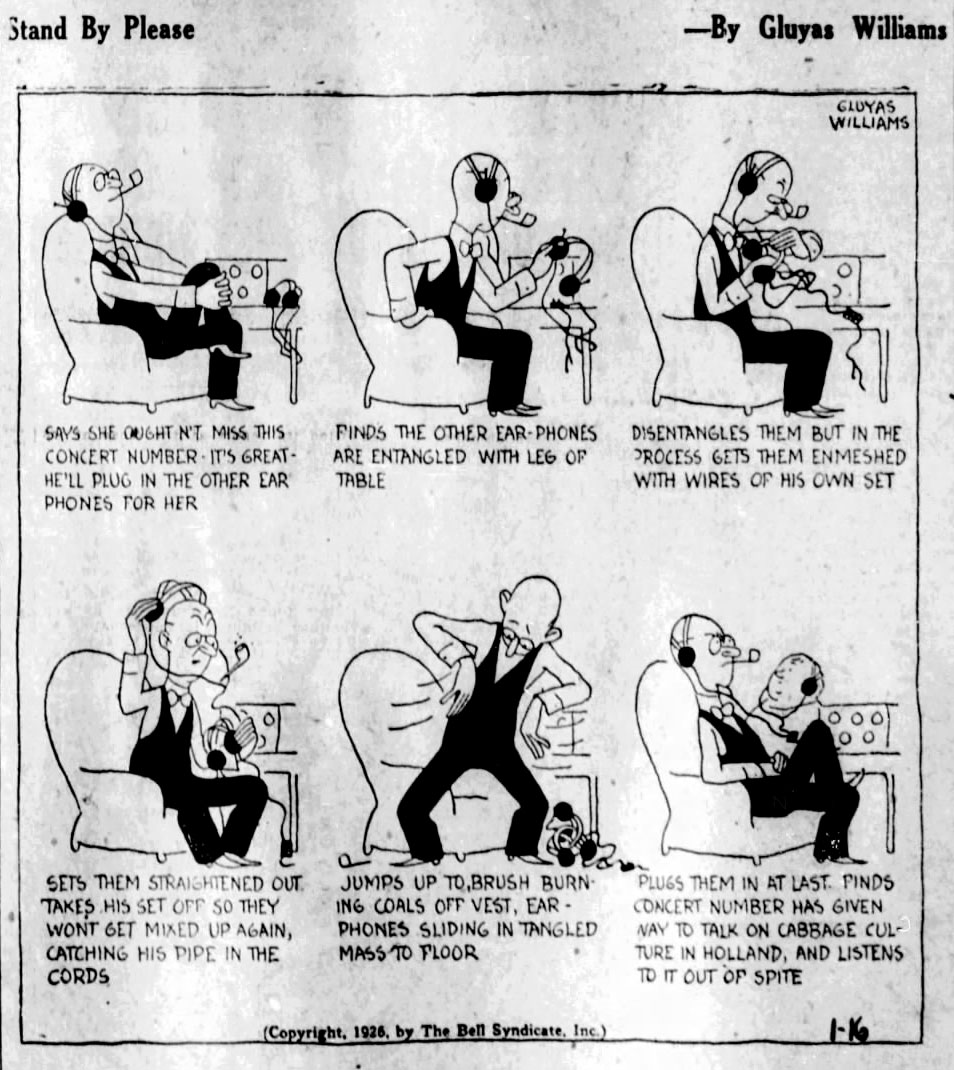

Other observational comedy by Williams was presented in a comic strip format, most prominently in 'Snapshots of…' (published in The Boston Globe from 11 September 1922 on) and, occasionally, 'Suburban Heights' too. In his one-panel cartoons, Williams was often forced to include lengthy summarizations underneath the drawing to describe how the characters found themselves in their particular situation. By using a comic strip style, he could simply visualize the foreplay and aftermath to these situations step by step, panel by panel. He could, for instance, show a man trying to kill time before his train arrives. Or a father trying to read his paper while constantly being interrupted by his curious son. The comic strip format was particularly efficient to poke fun at people stuck in repetitive behavior or needlessly time-wasting endeavors. For instance, a man going through several attempts to stick an already used stamp on a new envelope. Yet even when a character does little more than just go back and forth between the same motions, or simply sit in a chair looking around, Williams kept the artwork interesting. Each pose in each panel was still drawn individually, with small changes.

'Stand By Please' (The Sacramento Bee, 16 January 1926).

General audiences loved Williams' cartoons and comics, which, after a century passing by, have lost none of their timelessness and universality. He depicted humanity in its all-too-relatable clumsiness, awkwardness and repetitiveness. Anyone can easily project him or herself in trying to move a trunk across stairs, getting hopelessly lost in a department store or impatiently waiting for a movie to start in a theater. Williams claimed he never made things up, but simply kept his eyes open at all times. He could find inspiration in something as simple as a man discreetly trying to clean his dirty tie without anyone noticing him, or a small boy taking various poses while reading from the comfort of a big chair. In a 1975 interview, conducted by Richard Marshall, he said: "I'd watch for things to happen at the West Newton Station in the morning or evening - things like somebody trying to get through the station door to buy a paper, just as everyone else surges out to board the train; or trying to get a taxi at the station on a rainy night; or the way everyone in the station starts for the platform when a train rumbles by, and it's usually a freight train. All those little everyday occurrences can be built into cartoons."

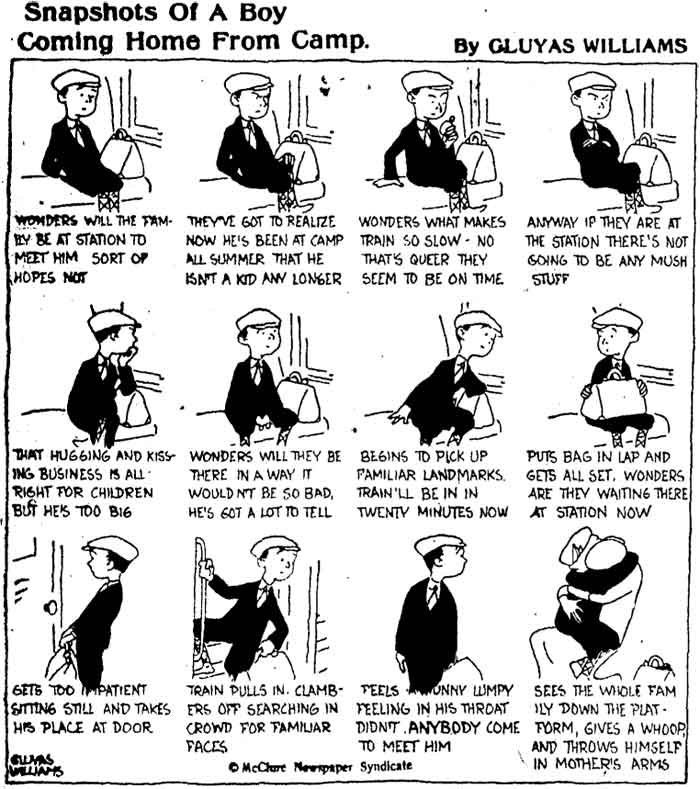

'Snapshots Of A Boy Coming Home From Camp'.

Williams' comedy is slightly satirical, but never malicious. He offers a witty view on people overreaching themselves or being caught in irritating but, at the same time, endearingly recognizable small-scale problems. Sometimes there isn't even a real punchline, just a heartwarming conclusion to all their ordeals. In a 'Snapshots' episode where a boy returns from summer camp, for instance, the kid is waiting inside the train. On one hand he anticipates being home again, on the other he hopes his family won't be there, because "that hugging and kissing business is alright for children, but he's too big." As the train reaches closer to its destination, the boy gets more anxious, worrying whether they'll be there at all. Even before the train has fully come to a halt, the kid is already moving to the door. As he steps on the platform, he doesn't see anybody he recognizes and starts to panic, only for his mother to come in and give him a warm hug.

In a reprint of an old interview, printed in The Boston Globe after Williams' passing in 1982, Williams explained his overall goal: "Trivialities interest me most. We spend the greater part of our lives struggling against things that don’t matter. Minor crises often aren’t comical at the moment, but viewed in perspective they take on overtones of humor. Two things I strive for in my cartoons - to bring the reader to smile at himself in the past or make it easier for him when the incident happens in the future."

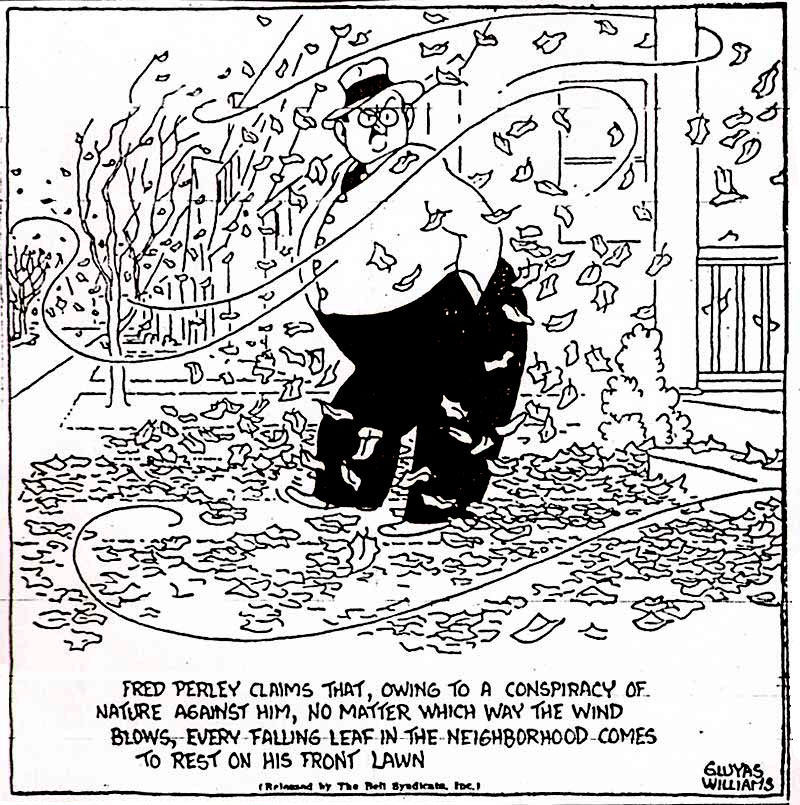

1939 cartoon with Fred Perley.

The inconsistency in titles and lack of genuine recurring characters might explain why Williams' cartoons were, on hand, popular, but didn't really increase his name recognition. Most characters in his work are anonymous and interchangeable. The only exceptions can be found in 'Snapshots Of…', where one child character is frequently named "Eddie Selzer" (no relation to the Looney Tunes producer of the same name), while an everyman with glasses and a Chaplin mustache is named Fred Perley.

Williams' cartoons have been collected in 'The Gluyas Williams Book' (with a foreword by Robert Benchley, 1929), 'Fellow Citizens' (1940) and 'Gluyas Williams Gallery' (1957).

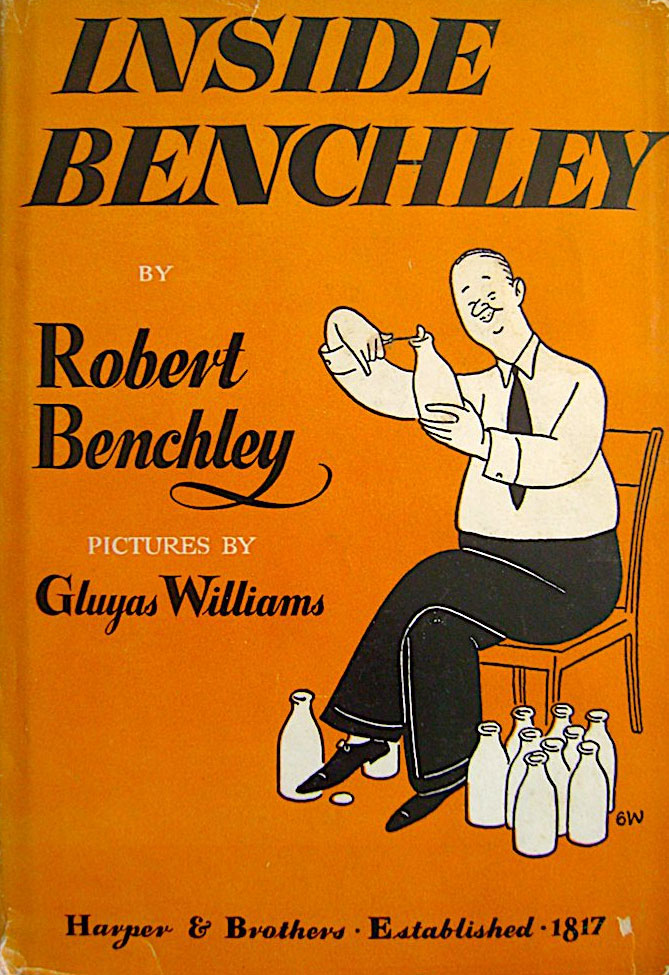

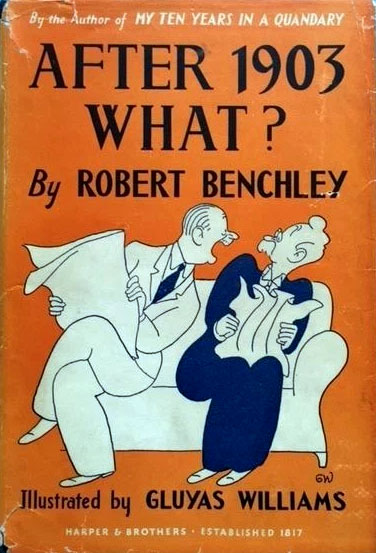

Illustrator

Williams was notable for illustrating the humorous columns of Robert Benchley in Vanity Fair magazine. He also designed the covers for Benchley's book compilations. The only downside was that Benchley was sometimes approached by people who complimented him on "his pictures". Williams also livened up Edward Streeter's novel 'Father of the Bride' (1948), famously adapted into two Hollywood movies, in 1950 starring Spencer Tracy and Elizabeth Taylor, and in 1991 starring Steve Martin and Kimberley Williams. He also livened up Edward Streeter's column collection 'Daily - Except Sundays'. He additionally provided drawings to Laurence McKinney's 'People of Note' (1948), Ralf Kircher's 'There's A Fly in This Room' (1946), 'Wrap It As A Gift' (1947), Corey Ford's 'How to Guess Your Age' (1950) and David McCord's 'The Camp at Lockjaw' (1952).

As a commercial illustrator, Williams also created art for companies, among them Bell Telephone, Michelin, Rand McNally & Co and Texaco.

Legacy and influence

Williams was known as a witty, but reserved man. In his spare time, he played bridge and billiards, while also enjoying sailing. He kept a spare pile of drawings in a local bank, just in case his studio might be subjected to some disaster that would destroy his entire archive. However, in 1933 a sudden bank holiday was declared, just when Williams faced a deadline and wanted to use some of the drawings he had stashed away. The Boston Globe went through the effort to contact the bank and arrange it so that Williams could enter the building under guard, just to get his drawings.

In 1953, Gluyas Williams retired, mostly because he felt 65 was a good age to put his pencil down. Yet he was also afraid that continuing might strain his eyesight. He lived for almost three more decades, passing away in 1982, at age 93.

Gluyas Williams was an influence on Fougasse (Kenneth Bird), John Blair Moore and Edward Sorel. In 2019, the publishing company Rosebud released several compilations of Williams' cartoons, titled 'Short Stories', 'People of Note', 'The Wide Open Spaces' and 'And So to Bed'.