'Up' in Linus #101 (1973). Translation: "Nobody forced me. I had no accomplices... I worked alone! I am a Stirnerarian individualist anarchist!" (a reference to philosopher Max Stirner, founder of individualist anarchism). - "That's a nice quote from someone who believes in anarchism!".

Alfredo Chiappori was an Italian political cartoonist and comic artist. He is best known for the gag series 'Up Il Sovversivo' (1970-1976), which ran in the magazine Linus. On the surface, Up appears to revolve around a strange man who lives upside down on the ceiling. From a deeper perspective, the feature offers biting political-social satire with an anti-authoritarian stance. Being an utter contrarian, Up doesn't conform to society's expectations, rules and dogmas. The comic fitted the free-spirited atmosphere of the 1960s and gained a cult following. 'Up Il Sovversivo' is widely regarded as a milestone in satirical cartoons, bringing topical, left-wing humor back to the forefront in post-war Italy. The series paved the way for dozens of other similar subversive comics series, making Chiappori one of the most influential Italian cartoonists of the 1960s and 1970s. Another well-known comic series by Chiappori is the historical-educational 'Storie d'Italia' (1977-1981), which offers a funny, but well-researched look at his nation's past, from 1846 up until 1925. Later in his career, Chiappori was a notable editorial cartoonist, novelist, painter and playwright, working extensively for Panorama magazine.

Early life and career

Alfredo Chiappori was born in 1943 in Lecco, in the Northern region of Lombardy. His father was a journalist and theater critic. During World War II, he joined the anti-fascist partisan army, but was executed when Alfredo was only one year old. After the war, Chiappori became an apprentice of painter Orlando Sora. The teen studied drawing nudes at the Academy of Brera and later attended the Art Institute of Fano under the guidance of the sculptor Edgardo Mannucci. Among Chiappori's main graphic influences were Walt Disney, Charles M. Schulz and Georges Wolinski. Later in life, he also expressed admiration for Sergio Staino and Altan.

After graduation in 1965, Chiappori tried to earn a living as a painter, but soon realized he needed a more lucrative source of income. Between 1967 and 1969, he worked as an art teacher at the Liceo Scientifico in his hometown of Lecco. However, he soon gave up this job to become a full-time cartoonist. During the 1960s, Chiappori already published satirical cartoons in the local newspaper Giornale di Lecco and the Milanese weekly news magazine Epoca. After 1967, his work expanded, and his drawings could be found in La Provincia. In 1969, he made his first drawing for the alternative comic magazine Linus, illustrating an article featuring criticism by Ranieri Carano.

First two book publications of 'Up Il Sovversivo', published by Giangiacomo Feltrinelli.

Up Il Sovversivo

In the late 1960s, Chiappori created his signature comic series, 'Up Il Sovversivo' ("Up the Subversive"), also known as simply 'Up'. Perfectly encapsulating the spirit of the time, the feature was inspired by the May 1968 student demonstrations. The title character Up is a rebellious young man. He doesn't conform to the system, nor any of its rules. In fact, he literally breaks the laws of physics by living upside down. Up is able to walk on ceilings and even thin air, giving him a different perspective on life. In many gags, Up debates with conventional people who try to challenge him. Politicians, magistrates, generals, soldiers, policemen, priests, bishops, teachers, college professors want him to behave and obey, but Up regularly has a poignant observation or witty response ready. He doesn't believe in what the authorities tell him. To him, their idea of a "civilized society" is bogus. Up points out the holes in their theories and dogmatic thinking. The ceiling dweller literally and figuratively does the exact opposite of what society expects from him. And by living on the ceiling, he can never be oppressed or “kept down”.

'Up Il Sovversivo' was strongly influenced by the French satirical and taboo-breaking magazine Hara Kiri. Chiappori discovered Hara Kiri (nowadays Charlie-Hebdo) in 1968, during a trip to Paris at the height of the student demonstrations. Its columns, comics and satirical ads struck him "like lightning", as he later described. It convinced him to create a similar subversive comic. Originally, Chiappori wanted to use a policeman as his main character, but a bumbling, tyrannical police officer worked better as an adversary. Instead, he made his protagonist a young, rebellious everyman. 'Up Il Sovversivo' serves as a platform for Chiappori's personal ideas. The series offers anarchic, left-wing commentary on conservative politics, outdated values, conventional thinking, religion, police violence and neo-fascism. Just like the cartoonists of Hara-Kiri, he uses a simple, linear style with big-nosed characters. Chiappori also enjoys working with silhouette figures and light-and-dark contrasts.

'Up' in Linus #113 (1974). Translation: "Who of these men of the SID is responsible for destroying the SIFAR files?". The SIFAR Files were police files about several high-profile people from Italian politics, the military, media, unions, journalism and bishops, including the Pope, collected by the Italian secret service (SID or SIFAR). In 1965 several scandals led to the disbandment of the SIFAR, who changed its name to the SID. A parliamentary commission investigated the files, despite many obstructions by the christian-democratic party and suspicious illnesses and deaths from investigators. In 1974 Italian Prime Minister Giulio Andreotti ordered the destruction of 34.000 "illegal" SIFAR files.

'Up Il Sovversivo' is often credited with reintroducing and popularizing topical satire in post-war Italy. Before the rise of Benito Mussolini in 1922, the country had a vivid left-wing satirical tradition. But once Fascism got Italy in its stronghold, these voices were slowly but surely silenced. After World War II, Italy became a democracy again, but at the same time succumbed into political chaos. Many governments came and fell, sometimes in a matter of months. Far-right and far-left parties actively tried to prevent each other from gaining too much power, sometimes through violent means. Assassinations, terrorism and Mafia intrigues frequently made headlines. Most Italians were not in the mood for anything that questioned the system, so writers and cartoonists kept their comedy light-hearted and apolitical - out of fear of polarizing audiences, but also because they were scared of violent, even fatal repercussions. However, by the end of the 1960s, times were so turbulent that Chiappori couldn't remain silent. 'Up Il Sovversivo' dared to criticize the government, brutal police force and the Vatican's unquestioned authority on political-social matters. It was also more in line with younger generations demanding radical changes.

Drawing the first gag in 1968, the early episodes of 'Up Il Sovversivo' were printed in La Provincia. In early 1970, the publisher Giangiacomo Feltrinelli released 'Up Il Sovversivo' in book format. In the following years, Feltrinelli remained the publisher of Chiappori's books. Between 1973 and 1976, the 'Up' feature ran on a regular basis in the Italian monthly comic magazine Linus (issues #94 up until #136), where it quickly gained a cult following. Episodes were often accompanied by a critical reflection on their "deeper meaning", written by Ranieri Carano.

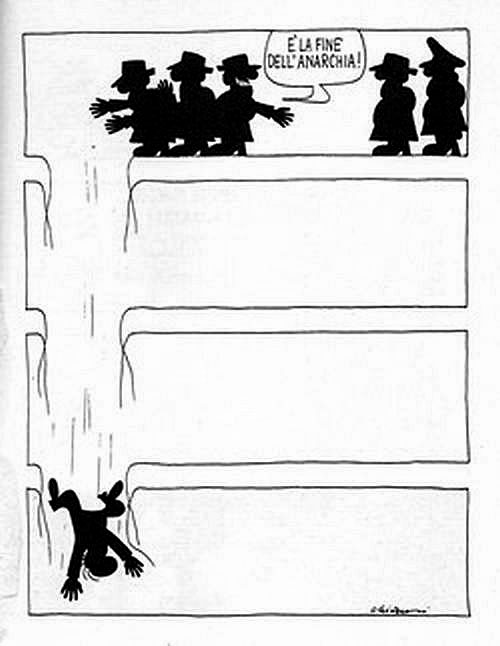

Scene from 'Vado, L'Arresto e Torno' (1973). Translation: "This is the end of anarchy!".

Vado, L'Arresto e Torno

While most episodes of 'Up Il Sovversivo' were gag comics, Chiappori published one longer narrative with the character. In 1973, Feltrinelli released 'Vado, L'Arresto e Torno', a comic book inspired by the 1969 terrorist attack at the National Agricultural Bank in Piazza Fontana, Milan. 17 people died and 88 were wounded. The culprits were the neo-fascist paramilitary movement Ordine Nuovo. In the following years, several other terrorist attacks followed, some by Ordine Nuovo and other neo-fascist groups, others by Communist terrorists like the Brigate Rosse ("Red Brigades"). It caused a climate of fear in Italy, where politicians took extreme measures to "maintain the country's safety", declaring the "state of emergency". Naturally, the polarization between various left-wing and right-wing ideologies divided the population only further. In 'Vado, L'Arresto e Torno', many authorities conspire to finally arrest Up. Through draconic laws, the country becomes a police state. In the end, all opposition is silenced. Chiappori's bleak vision still receives a spark of hope, though. On the final page, the façade of the authorities suddenly crumbles down. With everything in ruins, Up is the only rebel still standing.

'Coerenza', from Linus #183 (1980). Translation: "Beyond the polemic tones which always accompany an election campaign, I shouldn't forget [to say to] our comrades that our [party] line is still in talks with the DC (Democrazia Christiana, AKA the Christian Democratic Party). The PCI (Partito Comunista Italiano, AKA the Communist Party) has lost the vote, but not its vices!".

Success, and other publications in the 1970s

'Up Il Sovversivo' marked a veritable boom in topical satire in Italy. In the late 1960s and especially the 1970s, many other cartoonists and comic artists created their own subversive series. Many were unapologetically anarchic, biting and left-wing in tone. Chiappori was hailed as one of Italy's most influential cartoonists and able to build out a productive career. From 1970 on, his drawings ran in the left-wing magazine Compagni, followed by the graphic humor magazine Ca Balà a year later. In 1973, his cartoons appeared in Rassegna Sindacale and Fabbrica e Stato, followed by La Stampa, La Unità, La Repubblica, Il Corriere della Sera and L'Erba Voglio. In 1972, Chiappori created the comic book 'Alfreud' (Feltrinelli, 1972). After the conclusion of 'Up' in 1976, Chiappori remained a regular in Linus magazine with the shorter-lived features 'Kaspar Pfistermeister' (1977, issues #145-#147) and 'Coerenza' (1980, issues #178-#188).

With political writer Forebraccio - a journalist for the Communist newspaper L'Unità - Chiappori wrote the book 'Il Belpaese' (Feltrinelli, 1973). Despite its romantic sounding title (literally "The Fair Country"), the book doesn't offer a positive view of Italy. A similarly titled cartoon column ran in the weekly Panorama. Chiappori additionally contributed weekly political cartoons to the Roman daily paper Paese Sera. Together with Oreste del Buno, chief editor of Linus, he also created the political comic 'Padroni e Padrini' ("Bosses and Godfathers", 1974), published in book format by Feltrinelli.

Chiappori's Lockheed game (1976).

Parody games

For Panorama magazine, Chiappori designed a series of playing cards in 1979, depicting Italian politicians, bishops, magistrates, policemen and other officials. The cards were produced by Windmill Playing Card Company in collaboration with Arnoldo Mondadori Editore. For Linus, Chiappori made a 1976 board game parody, 'Il Gioco de l'Ockheed'. Spoofing the classic racing board game 'Game of the Goose' ('Gioco dell'Oca' in Italian), it was originally an insert within an issue of Linus. Chiappori designed the entire game, which referenced the 1976 bribery scandal within the U.S. airplane company Lockheed. At the time, the Lockheed affair made major headlines, especially since many heads of state were accused of involvement, including Dutch prince Bernhard and the Italian President Giovanni Leone, among other politicians. Players of Chiappori's game travel past all the major institutions in Italy, including the Cassa del Mezzogiorno (Bank of the Southern Regions), national broadcasting company RAI, advertising firm SIPRA, the Italian Ministry of Defense and the presidential house. On some spaces the CIA is represented, allowing players to throw their dice again. On others the Mafia "kills" you. Sometimes players are lucky: if the Mafia merely kidnaps you, paying ransom allows you to start all over again. The Lockheed Company itself is also present, complete with suspicious "little brown envelopes". The winner is the one who manages to enter the presidential palace.

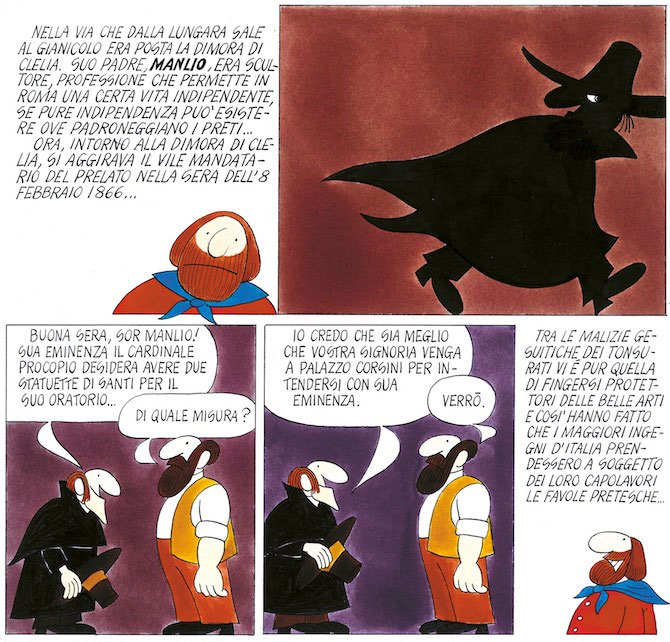

'La Storie d'Italia', featuring Giuseppe Garibaldi.

La Storie d'Italia

While Chiappori was well appreciated within the pages of Linus, chief editor Oreste del Buono once asked him to make a more ambitious and timeless comic strip that didn't just comment on current and quickly dated events. The idea arose to make a comic strip about Italy's past, serialized in Panorama magazine and published in book format by Giangiacomo Feltrinelli. Logically, Chiappori looked at the nation's founder, Giuseppe Garibaldi. In 1870, Garibaldi had written the novel 'Clelia, Il Governo dei Preti' ('Clelia, the Government of Priests'), set in Rome and highly critical of the Church as an institution. Garibaldi nevertheless didn't write it out of any high ambitions, he simply needed some badly needed cash. Chiappori felt his purely monetary motivation showed up in the quality of the book. He confirmed it was "naïve and very badly written". But as one of the few novels written by Italy's founder, it still held his interest. Plus, since Chiappori was highly anti-clerical himself, he felt it would be a fitting work to dust off and reintroduce to modern readers.

'Fiumicino - Il Bel Paese', from: 'La Storie d'Italia' (1980).

But when Chiappori started with the project, it soon became clear that he needed to put the narrative into a historical context. He consulted well-known historians like Giorgio Candeloro and Franco della Peruta, whereupon the comic changed in scope. Instead of a mere adaptation of Garibaldi's book, it grew into an ambitious history of Italy, from the 1861 unification of all its city states and how it developed in the decades beyond. Still, Chiappori wanted to avoid a dry history lesson. He deliberately named his project 'Storie d'Italia' ("Stories about Italy", 1977-1981), since most of what we know about the past is not reliable as "historical fact". At best, they are a bunch of anecdotes, or "stories". Chiappori also added a lot of humor. He mocks the decisions of "our forefathers", though doesn't stray away from his educational goals.

After serialization in Panorama, the first volume of 'Storie d'Italia' was published in 1977 by Feltrinelli. It focuses on the period 1860-1870. The second volume, released in 1978, goes back in the past, commenting on the prelude to Italy's foundation, all the way up to the year 1846. From the third volume (1979) on, the books are chronological. The 1979 volume reflects on all the events from 1870 until 1896. The fourth volume (1980) continues from 1896 until 1918. The fifth and final volume (1981), covers the events up until 1925. Sadly, Chiappori never made any extra sequels. Though in the 1980s, Panorama magazine ran a special feature, 'Storie d'Italia. Di Scandalo in Scandalo', tackling the period after World War II, in particular all the political scandals. Apart from Chiappori, it featured graphic contributions by Giuseppe Coco & Antonio Tettamanti, Filippo Scozzari, Renato Calligaro, Luca Novelli, Maurizio Bovarini, Ro Marcenaro, Lorenzo Mattotti & Antonio Tettamanti, Sergio Staino and Francesco Tullio Altan.

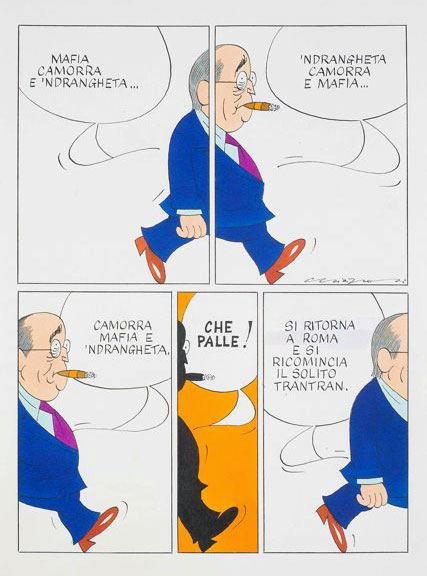

Cartoon for Panorama magazine (1980). Translation: "Mafia, Camorra and 'Ndrangheta, 'Ndrangheta, Camorra and Mafia, Camorra, Mafia and 'Ndrangheta. What a bunch of crap! We return to Rome and restart the usual rut."

Graphic contributions

Alfredo Chiappori contributed cartoons to 'Chi Gioca alla Crisi' (Books' Store, 1976), a satirical commentary on the economic crisis, filled with work by cartoonists from the magazine Pelo e Contropelo. He designed the album covers of Paolo Pietrangeli's 'Karlmarxstrasse' (1974) and 'Lo Sconfronto' (1976). He also drew the comic strip on the cover of Michele L. Straniero's record 'Coi Comforts della Religione' (1976). In line with the themes of the title (literally: "Comforted by Religion"), the comic depicts a man who, at first, feels sheltered by the Church. The institution offers him help and spiritual answers. But in the final panel this religious shelter turns out to be a dogmatic cage.

Recognition

Chiappori was honored with the 1974 Prix Révélation ("Revelation Prize") at the International Comic Festival of Angoulême, France. In 1976, he received the First Prize for "Humorous Commentary" at the Festival of Siena. the artist won a 1979 "Golden Palm" for Book Illustration at the International Salon of Bordighera. In 1997, during the Premio Dessì Awards ceremony, Chiappori became the first cartoonist to receive the "Special Jury Award" for his literary output. In 2000, he also won the Giorgio Cavallo Award for Humor and Satire.Chiappori received a golden medal in 2003, from his hometown Leco, declaring him a "Citizen of Merit".

Chiappori also frequently exhibited his paintings. During these public events, art critics Giulio Carlo Argan and Umberto Eco were present to praise his work. In 2005, Chiappori also exhibited thematic paintings based on the Holy Scripture.

Final years and death

Later in his career, Chiappori focused on writing novels. Among his titles were 'Il Porto della Fortuna' (Rizzoli, Milano, 1997), 'La Breva. Storie di iago' (Lipomo (CPO), Dominioni, 2001), 'Il Mistero del Lucy Fair' (Milano, Dalai Editore, 2002) and 'Franco Destino. Un'Infanzia d'Artista' (Venezia, Marsilio, 2004). He also contributed to theatrical plays, including collaborations with Peter Brook and Jerzy Grotowski. In 2022, Alfredo Chiappori passed away, at age 79.

Alfredo Chiappori.