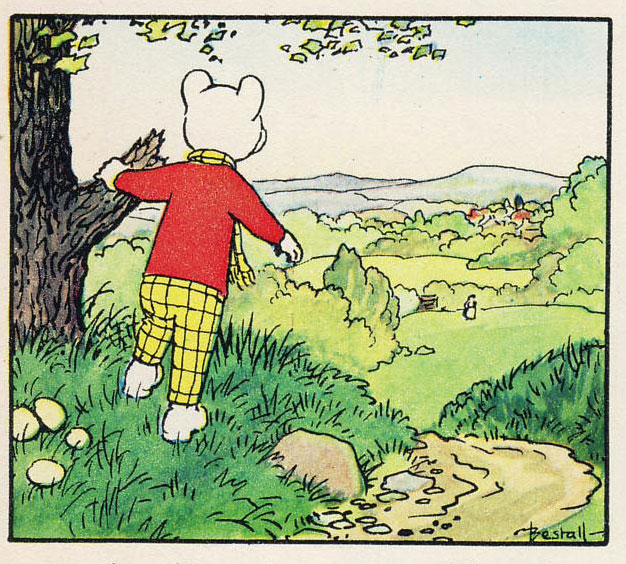

'Rupert and Miranda' (Rupert Annual 1953).

Alfred Bestall was a British comic artist, illustrator and origamist. Between 1935 and 1965 he was the second artist to continue the adventures of 'Rupert Bear' in the Daily Express. During his run, the comic strip reached the height of its popularity and sales. Bestall shaped the adventures of the little white bear into the way they're best recognized today. He oversaw the transition to color and modernized the series. The artist expanded the cast by giving Nutwood several new inhabitants. Overall, he gave 'Rupert' a fun and escapist atmosphere. Artwork and stories reached such a level of quality that many regard him as the finest 'Rupert' creator of all time. His stories are reprinted to this day and are the subject of a fond cult following.

Early life and career

Alfred Edmeades Bestall was born in 1892 in Mandalay, Upper Burma (nowadays Myanmar), back when the country was still a British colony. His father was a methodist missionary. In 1897, Bestall and his sister Maisie returned to England. They stayed with relatives and colleagues of their father, while their parents stayed behind in South East Asia. Only in 1910, the Bestall family moved to England for good. As a child, Bestall was a stutterer, caused by a spinal injury at an early age. He never knew the nature of this accident and his parents refused to discuss it. However, he believed it might have been a fall from a pony. Bestall's spinal problem kept bugging him until age 45, when an osteopath managed to cure him.

Bestall spent his childhood in North Wales and the English countryside, which inspired many backgrounds in his 'Rupert Bear' stories. In particular, the scenery around the Snowdonia area is reflected in his artwork. He studied at the Birmingham Central School of Art (nowadays the Birmingham College of Art) and just started lessons at the LCC Central School of Arts and Crafts in Camden, when the First World War broke out. Bestall joined the British Army and fought in West Flanders, Belgium. He transported ammunition and other necessities to the troops in the trenches. Despite the horror around him, he found time to draw portraits of and for his fellow recruits and officers. Some of his work appeared in the army magazine Blighty. Only after the war did Bestall continue his studies in Camden.

(Children's book) illustrations

By 1920, Graham Hopkins of the Byron Agency got Bestall a job illustrating Enid Blyton's children's books. He livened up the pages of some of her earliest books: 'A Book of Little Plays' (1927) and 'The Play's the Thing' (1927). Later he also illustrated Blyton's 'Plays for Older Children' (1941) and the novel 'The Boy Next Door' (1944). Throughout the 1920s and early 1930s, Bestall's drawings could be seen in numerous children's books. Some were reprints of classic stories, such as Alexandre Dumas' 'The Black Tulip' (1920) and 'The Three Musketeers' (1932), others were based on folklore, such as 'The Magic Apple and Other Stories' (George Newnes Limited, 1926) and 'Mother Goose's Nursery Rhymes' (1939). He collaborated with William H. Lax on 'Lax His Book: The Autobiography' (1928) and 'Let's Go To Poplar!' (1932). Other books he decorated during the interbellum were Evelyn Smith's 'Myth & Legends of Many Lands' (1930), Stephen Southwold's 'True Tales of an Old Shellback' (1930), Agnes Frome's 'The Disappearing Trick' (1933), Dudley Glass's 'The Spanish Gold-Fish' (1934) and Hylton Cleaver's 'The Haunted Holiday' (1934).

In the 1920s Alfred Bestall became a painter-illustrator for the Amalgamated Press; his art ran in the publisher's Schoolgirl's Own Annuals between 1923 and 1942. The busy artist made cartoons and illustrations for Punch, Tatler, Eve, Passing Show and The Strand as well. He illustrated Ethel Manning's parodies of A.A. Milne's 'Winnie-the-Pooh', mimicking E.H. Shepard's style.

Once Bestall became preoccupied with 'Rupert', he found less time for other illustration assignments. Still, he managed to liven up the pages of Fay Inchfawn's 'Salute to the Village' (1943), Mabel Buchanan's 'The Land of the Christmas Stocking' (1948), Alfred Dunning's 'A Book of Magic Rhymes' (1948), Charles Constant's 'The Treasure Hunt and the Circus Mystery' (1955), John Crompton's 'A Hive of Bees' (1958) and Eirwen Jones' 'Folk Tales of Wales' (1964).

1925 Punch cartoon by Alfred Bestall.

Rupert Bear

Since 1920, Mary Tourtel and her husband Herbert Sidney Tourtel were the creative minds behind the success of 'Rupert Bear', the popular children's comic in the Daily Express. However, in 1930 Herbert passed away, leaving his widow behind in permanent grief. Mary continued the series on her own, but had lost her joy. The stories became increasingly darker and bleaker, while her eyesight deteriorated. More and more the paper had to rely on reprints. In 1933 a replacement artist was hired, Wasdale Brown, who created his own version of Rupert for the children's supplement The Daily Express' Children's Own. Unfortunately this comic was so off-model that the editors clearly needed someone better. In 1935 they approached Alfred Bestall. Since he was unfamiliar with the adventures of the little bear, he first studied Tourtel's artwork. After a few try-outs, he felt he could properly mimic her style. The Daily Express gave him only six weeks to churn out a story. Bestall feared he wouldn't be able to pull it off, but once he started, his inspiration came easy. On 28 June 1935, Bestall's first story, 'Rupert, Algy and the Smugglers', took off in the papers. Although he was a "temporary replacement", the editorial staff was so pleased with his work that he became Mary Tourtel's official successor. Though out of respect he didn't sign his work until after her death. The first story to bear his full signature was 'Rupert and Ting-Ling' (27 May - 21 July 1948). In the 1948 annual he signed his artwork with a simple letter "B".

Alfred Bestall was specifically instructed to continue Rupert's successful formula, but refrain from the dark and depressing themes of Tourtel's final years. Stanley Marshall, editor of The Daily Express' children's section, no longer wanted scary or evil characters. The series had to be happy and cheerful again. In the annuals, Bestall gave Rupert much brighter clothing. His blue jumper became red and his grey checkered scarf and trousers yellow. In Tourtel's stories Rupert sometimes wasn't seen for days. Bestall injected more comedy in the series and made the bear the focus again. His editors insisted that Rupert should appear in every panel. A direct result of this approach was that the bear became more active and assertive than he'd ever been in Tourtel's comics, where he is basically a helpless wanderer.

Bestall was additionally asked to leave magic and fairies behind. Tourtel often used magic as a way to write herself out of a narrative corner. Initially, Bestall followed all these instructions. He avoided scary elements or magical situations and his stories became grounded in everyday reality. Cars, motorcycles, aeroplanes, helicopters and machines play a more prominent role. Yet gradually, magic and villains made their return, though Bestall used them sparingly and with more creativity.

During World War II, Alfred Bestall again served his country, working as an air raid warden in Surbiton, Surrey. 'Rupert' continued in the papers, despite paper shortage. The British government felt the bear was important to "keep up public morale", and even subsidized production. Chief editor Lord Beaverbook obtained paper supplies to continue distribution of new annuals throughout the war. After the war, Bestall worked through the Byron Studios in London for another two decades. His goddaughter, Caroline Bott, recalled that Bestall used to think up stories while mowing the grass. He made most of his artwork late at night in his studio. During Mary Tourtel's run, 'Rupert' appeared in the paper with only one panel a day. Bestall, on the other hand, had to draw two daily panels. Each took two hours to make. And he usually drew three at once, to have one in advance.

'Rupert and the Iceberg' (Rupert Annual 1940).

Rupert: cast expansion

Alfred Bestall transformed Rupert's home village of Nutwood into its current form. Even though the village was not always consistent in its look, he still turned it into a fairly believable, three-dimensional setting. Bestall expanded the family tree of many characters created by Tourtel. He gave Rupert an uncle, Bruno, who often takes him out on trips in his motor car. Podgy Pig's cousin Rosalie was introduced, and Willie Mouse was given a country cousin named Rastus, in direct reference to the fable 'The Country Mouse and the City Mouse'. The Wise Old Goat's family was expanded with a sister, Grandma Goat, and his little cousin Billy Goat.

Bestall created completely new characters too. Notable additions are Freddy and Ferdie Fox, two mischievous fox-faced twins. They are the bad children in Rupert's neighborhood, although the little white bear always forgives them when they show remorse after their punishment. Gregory Guinea Pig is always loyal to Rupert, but most of the time too scared to go on an adventure. Bestall gave Rupert two extra dog-faced comrades. Bingo is an intelligent white fox terrier and a good inventor. A fan theory claims the brainy, bespectacled dog was a self-portrait, but Bestall never confirmed or denied this. Pong Ping has the face of a Pekingese dog. He is excellent in math, magic and owns a pet Chinese dragon named Ming. His quick-temperedness is his only vice.

Pong Ping wasn't the only Chinese side character with magic powers introduced by Bestall. He also created two humans: the girl Tigerlily and her father, who is always referred to as The Chinese Conjurer. They live in a pagoda in Nutwood, where they conduct magic. Tigerlily's tricks often lead to trouble, which her father then has to solve. Another human friend with a descriptive name is The Professor. The bumbling, absent-minded inventor is assisted by a little person, originally referred to as "The Dwarf", but later named Bodkin. Bestall gave Nutwood several other adult villagers, such as the dog-faced policeman Constable Growler, lion-faced Dr. Lion and orangutan-faced headmaster Dr. Chimp, who may or not be related to another monkey, shopkeeper Mr. Chimp. Rupert has several human friends outside Nutwood. One of them is the friendly old bearded farmer Gaffer Jarge. The Sage of Um is a wizard who travels the world while sitting inside a huge umbrella. Sailor Sam and Captain Barnacle take the bear on sea trips. Near the ocean, a merboy, simply named The Merboy, sometimes swims to the surface to say "hello". A land counterpart is Rollo, a gypsy boy with a keen knowledge of nature. Rupert's most unusual human friends are the Girl Guides. They were actually based on a group of real-life guides from Bestall's church: Beryl Sweet, Pauline Coates and Janet Francksen. In 1947, they asked Bestall whether he could give them a role in the series. Bestall fulfilled their request, keeping their first names and even giving Beryl's black cat Dinky a role as well. Remarkably enough, the girls remained part of the cast even decades later.

'Rupert, Algy and the Cannibals' (Rupert Annual 1953).

Style

One advantage of drawing two panels a day was that Bestall had more opportunity to write longer and stronger narratives, with exciting cliffhangers. Fans agree that his run was the series' golden era. His stories express powerful imagination, while never forgetting the core ingredient: heart. Bestall was a rare example of a creator equally gifted in writing as in drawing. His stories and artwork were a genuine improvement over Tourtel. He redesigned The Old Wise Goat by replacing his hooves with hands, making his scientific skills more believable. Characters in Bestall's work have tremendous vitality in their facial expressions and movements. As a fan of silent movies, he knew how to communicate through images. His action scenes are dynamic and thrilling. Interestingly enough, Bestall never used onomatopoeia and rarely added movement lines. All his images are understandable purely on the strength of his drawing talent. The artist had a good sense of composition, making his fantasy worlds believable and versatile. Under his pencil, the landscapes in Rupert's world attain an almost poetic atmosphere.

Bestall came up with striking, surreal images, which etched themselves deep into the memories of his readers. In 'Rupert, Algy and the Cannibals' (1936), Rupert gets help from hundreds of snakes to chase a cannibal tribe away. In 'Rupert's Autumn Adventure' (1936), he uses spring-heeled boots to jump extraordinary distances and defeat a bunch of thieves. A flood in 'Rupert and the Floods' (1937) leaves Rupert and Bill's boat up in a tree once the water ebbs away. In 'Rupert and the Little Men' (1937), the bear discovers a cave where a mean man exploits gnomes for personal gain. In 'Rupert and the Flying Bottle' (1937), Podgy becomes weightless, so he has to be carried around like a balloon. The little bear visits the Bird Kingdom in 'Rupert and Bill in the Treetops' (1938), where all kinds of wonderful birds have established a monarchy. With the use of a magic wand, Willie Mouse accidentally sends his friends to another dimension in 'Rupert in Mysteryland' (1938). Rupert and Algy are kidnapped by a snowman in 'Rupert and King Frost' (1940). In 'Odmedod' (1940) the white bear meets a walking scarecrow, who helps him arrest spies. In 'Rupert and the Green Buzzer' (1953), our hero is startled to find a tree with a huge bump on its bark. It's not surprising that all these stories have become classics.

Controversy

Bestall's stories sometimes featured people from different races. Interestingly enough, the vast majority aren't portrayed in nowadays stereotypically offensive ways. They speak proper English, are drawn realistically and are friendly and helpful. Shining examples are the black minstrel in 'Rupert and the Ruby Ring' (1938) and the recurring Gypsy Boy character. Villains are usually white people, anthropomorphic animals or fantasy creatures. Bestall's work is notable for featuring a lot of people of Chinese descent. Maybe not surprisingly, since Bestall spent his early childhood in South East Asia. Besides Tigerlily, the Chinese Conjurer and Pong Ping, Rupert also met the Prince and Emperor of China. While it must be said that the Chinese characters walk around in old-fashioned costumes, complete with ponytails, the country as a whole is still depicted as an empire, even though it was already a republic since 1911. Bestall opted for a fairy tale version of China, just like the way he depicted Arabia, Africa or England, for that matter. Some old stories used outdated depictions of minority groups, which were altered for later reprints. For instance, the Professor's assistant was always referred to as "The Dwarf". He later received a name, Bodkin, to solve the matter. Only two of Bestall's 'Rupert' annuals are no longer reprinted because of unintentional racial offensiveness. In the 1946 and 1947 annuals, Rupert meets black tribespeople who all look like golliwog dolls, complete with big red lips, fluffy curls and dumb-founded expressions. Throughout these stories they are referred to as "golliwogs" or "coons". In this sole case, not just the choice of words, but the entire stories and artwork are problematic. As a result they are effectively banned.

The 1939 and 1944 Rupert Annuals.

Annuals

Besides the daily strip, the 'Rupert Annuals' became an important addition to the franchise. After Mary Tourtel's retirement, the Daily Express editors felt that after 16 years they had enough 'Rupert' stories to collect and reprint in book format. In August-September 1936, the annual compilation book series was launched, simply known as the 'Rupert Annuals'. The originals were quarto books in hardcover, printed in black-and-white with red tinting. Only the front and back covers were in color. Bestall designed each one up until 1973. During World War II, there was no board available, so the books were reduced to paperbacks and stayed that way for a decade. As a compensation, the annuals turned to full color from that moment on. After the war, more comic magazines launched annuals as well. To beat their rivals, the 1946 'Rupert' annual offered more than just comics. Games, coloring pages and origami lessons became a popular staple. This latter novelty was a suggestion from Bestall, who was quite skilled in making folded paper figurines. In 1967 it even landed him a job as vice president of the British Origami Society.

From 1950 on, the hardcover annuals were resumed. The edition of that year even sold a record 1.7 million copies! Original copies of old annuals by Bestall are collector's items today. New annuals are still published every year. They are traditionally released in the late summer, but sales always increase around Christmas time. Generations of British children have fond memories of receiving a 'Rupert' annual as Christmas present. Many wondered why the bear always had brown fur on the book covers, while he was colored white inside. This was a relic of the earliest book publications of the Tourtel era, which only had colored cover illustrations, with Rupert appearing as a brown bear. The stories themselves remained in black and white, like in the paper. In later book publications, the stories were given spot colors. To save money on ink, Rupert's skin remained white, giving him the resemblance of a polar bear. In 1973 editors decided to fix this discrepancy and made Rupert white on the cover too, without consulting Bestall first. The artist was so furious that he never illustrated another cover again.

Retirement, final years and death

In 1956 Alfred Bestall bought a cottage in Beddgelert, Snowdonia, North Wales, where he lived permanently from 1980 on. He lived together with his elderly mother and his disabled sister. In 1965 his mother passed away, so he dutifully took care of his sister himself, which motivated him to retire from the daily 'Rupert' production. On 22 July 1965 his final story, 'Rupert and the Winkybickies', came to an end. At that point, he'd written and drawn 274 'Rupert' stories, of which 224 were for the newspaper. 41 were written specifically for the Annuals and seven stories first appeared in the 'Adventure' series. In 1938 and 1939, Bestall also drew two 'Rupert' stories for the Boys' and Girls' Books of the Year series, though he later dismissed them as being substandard.

Alfred Bestall never married and spent most of his final years alone, suffering from bone cancer. When asked whether he would've wanted to have children, he answered that he had millions of them in his target audience. He felt a responsibility to give them quality stories with a strong moral: "The thought of Rupert being in people's homes and in so many children's heads was a perpetual anxiety to me". The artist made it his mission to personally reply to every letter children sent to him. At age 90, he broke his hip playing table tennis. When the chaplain visited him in the hospital, he joked: "I was only sorry I didn't return the shot." His hip was replaced through surgery. Alfred Bestall died in 1986 at age 93 at Wern Manor Nursing Home in Porthmadog, Wales.

Recognition

In 1985 Alfred Bestall was named a MBE (Member of the Order of the British Empire), but couldn't attend the ceremony because of his illness. Prince Charles (the future King Charles III) therefore sent him a congratulatory telemessage on his 93rd birthday with his award, also adding that he remembered his "marvellous illustrations" from his childhood. In May 2006 Bestall's house in 58 Cranes Park, Surbiton, London was commemorated with a blue plaque.

Successors

During Bestall's lifetime, additional artists were brought in to relieve Bestall from his workload and illustrate the 'Rupert' book publications. Enid Ash and Alex Cubie, for instance, illustrated most of the 'Rupert Adventure Series' between 1952 and 1962, although Bestall often had to fill in to draw Rupert's face. Doris Campbell became the colorist for the annuals.

After Bestall's retirement, most 'Rupert Bear' adventures for the Daily Express were written by his editors, subsequently Freddie Chaplain (1965-1979), James Henderson (1979-1990) and Ian Robinson (1990-2002). Between 1965 and 1985, several artists alternated on illustrating the stories, most notably Alex Cubie (1965-1979), Jenny Kisler (1965-1977), Lucy Matthews (1976-1985) and John Harrold (1976-1985). Sporadic illustrators were Wendy Arnot (1969-1970) and Enid Ash (1971-1973). While Bestall quit the daily production, he still contributed artwork to the 'Rupert' annuals until 1973. In 1985, John Harrold became the official 'Rupert' artist, and continued his daily adventures until the end of the newspaper strip in 2002. Since 2008, Stuart Trotter is the main Rupert artist in the annuals.

'Rupert Bear' story remounted to balloon comics format for Dutch Donald Duck weekly (as 'Bruintje Beer').

Legacy and influence

Throughout his active career, Alfred Bestall was an unsung artist. In the 1970s, comics enthusiasts tracked him down and gave him more recognition. Monty Python member Terry Jones made a TV documentary, 'The Rupert Bear Story' (1982), broadcast on Channel 4, in which he praised Bestall as a "genius". Jones interviewed former Beatle and 'Rupert' fan Paul McCartney, as well as Bestall himself. The broadcast made the veteran comic artist more famous among general audiences. Since Jones complained that Bestall's classics were difficult to find nowadays, the Daily Express issued reprints. The comic artist collaborated on a book to celebrate the bear's 50th anniversary, 'Rupert: A Bear's Life' (London, Pavilion Books, 1985), written by George Perry. He also received an MBE medal (Member of the Order of the British Empire) that year, making him the only 'Rupert' artist to receive that honor.

Even today, Bestall's stories remain beloved. No other 'Rupert' creator has written and drawn so many stories and no other has been reprinted so much. His work has overshadowed that of the series' creator, Mary Tourtel. While it's true that Tourtel laid the foundations for 'Rupert' and created the core cast, Bestall took the series to a different level. His artwork remains the standard for his successors. The fact that he wrote his own stories is also admired. Academics and scholars have called his stories important literature.

Alfred Bestall was an influence on Anthony Green and James Jarvis, the American Tessa Hulls and on the Dutchmen Marten Toonder, Piet Wijn and Thom Roep. Between 1987 and 1990, 'Rupert' stories by Alfred Bestall ran in the Dutch Disney weekly Donald Duck, adapted by chief editor Thom Roep into a balloon comics format.

Books about Alfred Bestall

The finest compilation of Bestall's work is 'Rupert Bear: A Celebration of Favourite Stories' (2020) which has a foreword by his granddaughter Caroline G. Bott and by British writer and former politician Gyles Brandreth. For those interested in Bestall's life and work, Caroline G. Bott's 'The Life and Works of Alfred Bestall' (Bloomsbury, London, 2003), is highly recommended. The book has a foreword by Paul McCartney.

Portrait of Bestall by John Harrold (Daily Express Annual 1985).