'Rupert and the Little Man in Green' (1933).

Mary Tourtel was a British children's book illustrator and comic artist, most famous as the spiritual mother of 'Rupert Bear' (1920- ). She was the first artist to draw his adventures, while her husband Herbert Bird Tourtel wrote the text captions. After his death she continued the series on her own. Although Tourtel only worked on the series during its first 15 years and is overshadowed by her direct successor Alfred Bestall, she can be credited with establishing the popular franchise as it is today. She created and designed many of the main characters: Rupert, his parents and best friends Bill Badger, Podgy Pig, Algy Pug, Edward Trunk, Willie Mouse, Reggie & Rex, Beppo and The Old Wise Goat. Already during her run, 'Rupert' was translated into other languages. Since her retirement, the bear with the yellow checkered scarf has become a timeless bestseller, adapted in many media and reaching iconic status in British pop culture. Still running in papers for over a century(!), 'Rupert Bear' is the longest-running continuous British comic series of all time.

Early life and career

Mary Tourtel was born in 1874 in Kent as Mary Caldwell. Her father was a stained-glass artist and a stonemason. Her elder brother Edmund became a talented animal painter in Africa, while another brother, Samuel Jr., continued the family's stained-glass tradition. Between 1884 and 1889, she took drawing lessons at the Simon Langton School for Girls. She studied at the Sidney Cooper School of Art (nowadays University for the Creative Arts) in Canterbury, and then at the Royal College of Art. At this latter school, she met her future husband, Herbert Bird Tourtel. Tourtel was a struggling poet from Guernsey, and he asked her whether she could liven up his first poetry publication with her illustrations. The end result was 'The Coming of Ragnarok' (1898), both of their literary debuts. Two years later, the couple got married, which led to her name change. Mary Tourtel's early illustration work was done for children's fantasy stories featuring cute animals, magic and elements from fairy tales and nursery rhymes. She illustrated Bruce Rogers' 'The Rabbit Book' (1900), the general publication 'Old King and Other Nursery Rhymes' (1906) and William Cowper's 'The Matchbox Book' (1910) - which was literally printed at a matchbox size. Tourtel also wrote and illustrated books of her own: 'A Horse Book' (1901), 'The Humpty Dumpty Book: Nursery Rhymes told in Pictures' (1902), 'The Three Little Foxes' (1903), 'Matchless ABC' (1903) and 'The Strange Adventures of Billy Rabbit' (1908).

'When Animals Work' (Daily Express, 30 May 1919).

The Daily Express

Since April 1900, Herbert Bird Tourtel had been farm reporter of the newspaper The Daily Express. By 1903, he became night editor and was later promoted to assistant chief editor. Mary Tourtel made her first picture stories in the young women's magazine The Girl's Realm, while her drawings for the series 'In Bobtail Land' (1919) ran in the Sunday edition of the Daily Express: the Sunday Express. That same year, The Daily Express also ran her daily series 'When Animals Work' (1919), in which she depicted anthropomorphic animals in human professions. Readers liked this feature so much that Sefton Fabrics produced handkerchiefs with images of the characters. In one scene of 'When Animals Work', a prototypical little bear and his parents are already seen.

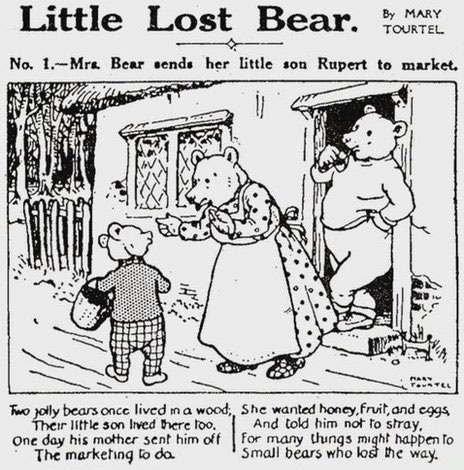

The very first episode of 'Rupert Bear', still nameless at the time, 8 November 1920.

Rupert Bear

In the 1910s, many newspapers in the United Kingdom published popular children's comics about funny animals. The Daily Mail had Charles Folkard's 'Teddy Tail' (1915-1926), while the Daily Mirror ran Julius Stafford Baker's 'Tiger Tim' (1904-1985) and Bertram Lamb and Austin Bowen Payne's 'Pip, Squeak and Wilfred' (1919-1956). The only paper to lack a strong comic series was The Daily Express. Editor R.D. Blumenfield asked Herbert Tourtel to search for an illustrator. He contacted many, before eventually asking his own wife. It was such an obvious choice that it simply didn't cross his mind. Mary Tourtel already had experience illustrating children's stories about anthropomorphic animals. She was a fine, realistic artist. And she basically already worked for the paper.

Ever since Clifford Berryman made his iconic "teddy bear" cartoon in 1902, cute bear dolls had been popular among children. This also translated into comics, with Julius Stafford Baker's 'Tiger Tim' (1904) and Kitsie Bridges and Dora McLaren's ' 'Bobby Bear' (1919) as direct predecessors of Rupert. An unconfirmed rumor claims the character was a suggestion from the grandmother of Peter Bessel, a member of the British Parliament, who came up for the Labour Party. Bessel's grandma had sent her idea to the newspaper and, according to legend, received £50 for the rights. What is certain is that right from the start, Herbert Tourtel wrote the texts, while Mary Tourtel provided the artwork. On 8 November 1920, the first episode of The Daily Express' new comic strip appeared in print. The original title was 'Little Lost Bear'. Only later did Rupert receive a name. Like most European comics at the time, it followed a text comics format, with text written underneath the images.

'Margot the Midget' (5 October 1921).

In Tourtel's original stories from the early 1920s, Rupert didn't always make an appearance. Sometimes he only turned up in the daily puzzle feature. Other times he was merely mentioned in the text, but not seen in the images. This was mostly a result of Tourtel not always being able to reach her deadlines. In the beginning, the Rupert stories were alternated with other comic features. Some were created by Tourtel as well, such as 'Margot the Midget' (1921-1925) and 'Father Christmas' (1921). Other gaps were filled by other artists, subsequently Tom Cottrell's 'Paper Cap' (1921), Dora Gibbon's 'Muffy in Moonland' (1922), Peter Bacon's 'The Toy Theatre Folk' (1922) and Weir Browne's 'The Robin's Surprise' (1923). However, by 1926 Rupert became the paper's main star and Margot was regulated to the role of side character.

Unlike most long-running comic characters, Rupert's design was fairly consistent from the start. Only his pants were a bit baggier. And since the comics were published in black and white, the color of Rupert's fur and clothing hadn't been determined yet. The first eight 'Rupert' books, published in the 1920s, only had colored cover illustrations. Later books had colored interiors as well. Tourtel originally made Rupert's jumper shirt blue and his scarf and trousers grey. His fur was brown. It wasn't until The Daily Express had to save money on ink that Rupert's skin became white, giving him the resemblance of a polar bear. Only after Alfred Bestall took over the series in 1935, Rupert finally received his iconic red shirt and yellow-checkered scarf. Nevertheless up until 1973, Rupert's skin was still colored brown on book covers, while being white in the interior story pages.

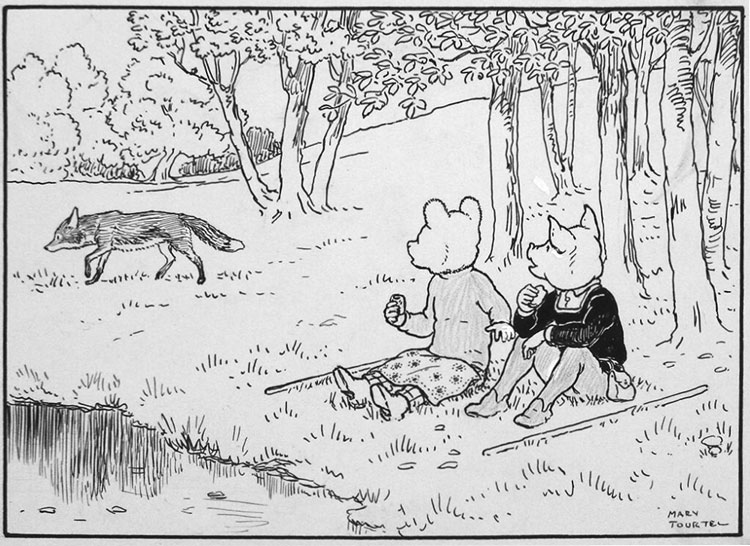

'Rupert Bear', 'Up the Spiral Stairs'.

Style and cast

Tourtel established Rupert's universe. The little bear lives together with his parents in a cozy village set in the green English countryside, called Nutwood. Hills, meadows, lakes and forests offer an idyllic landscape. The time period is vaguely defined. The stories are clearly set in the modern age, yet Rupert also encounters characters and locations more in tune with the Middle Ages, the Baroque or Victorian era. Fans are particularly fond of the nostalgic atmosphere in the classic stories made between the two world wars.

Tourtel created most of the core cast members used by later artists. Anthropomorphic animals and human characters live side by side. Rupert's best friend and sidekick is Bill Badger. While Rupert is generally nice, polite, smart and incorruptible, Bill is naughty, scared and easily angry. Another good friend with a fondness for playing tricks is Algy Pug, a pug dog. Algy is actually older than the series itself, as Tourtel already used him in one of her early children's books. Rupert is also best pals with Podgy Pig who, like most pigs, can be greedy and lazy. Among his other friends are the twin rabbits Reggie and Rex, who also own a pet monkey named Beppo. Interestingly enough, all animals are drawn the same size, even Rupert's friend Edward Trunk – who is a strong elephant – and the timid Willie Mouse. Basically they are human children with animal heads. Tourtel also created the Wise Old Goat, an adult mountain goat whom Rupert often asks for advice.

The Old Wise Goat returns Rupert home in 'Rupert and Prince Humpty-Dumpty' (1931).

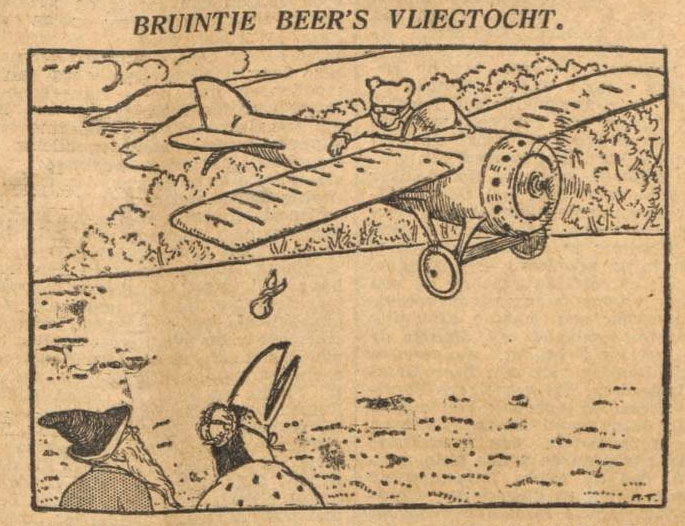

Tourtel also established the basic pattern for the 'Rupert' stories. Each tale starts off in Nutwood, where Rupert and his friends are playing outside, when they suddenly get caught up in a magical, fairy tale-like adventure. It usually brings the characters to dreamy, faraway lands. When the problems are solved, Rupert returns home safely to his parents, who are usually only mildly concerned about the adventures he experienced. Mary Tourtel and her husband were enthusiastic travelers themselves, which explains why Rupert rarely stays at home. Throughout the years, the Tourtels visited several countries, like Italy, Egypt and India. During the Great War, Herbert was fascinated by the newly formed RAF and wrote under the name of Icarus about how air travel would revolutionize tourist travel. In 1919, he was given two tickets for the inaugural in a converted Handly Page 400 bomber from the London Borough of Hounslow to Brussels, Belgium. There were six passengers on board of this record breaking flight and the pilot sat outside. It was as a result of this flight that Herbert, who wrote the stories, had Rupert flying everywhere on his adventures. The flight was featured in a Samson Low Little Yellow Book series as 'Rupert and Ted's Aeroplane Adventure'. Mary Tourtel later expressed she was so fond of flying because it enabled "seeing the land as the birds saw it".

In the early 'Rupert' stories, Tourtel often took inspiration from well known fairy tales and nursery rhymes. In one story, Rupert finds a Sugar-Plum House, not unlike the candy house in 'Hansel & Gretel'. In another story he is brought home by Puss-In-Boots. Despite her target audience, Tourtel didn't sugarcoat her content. Like traditional fairy tales, her stories could be quite dark and grim, heightened by the realistic drawing style. In 'Rupert and the Magic Toyman' (1922) for instance, an evil toymaker turns every intruder into wood. A diabolical dwarf named Grimblegrouch (in itself reminiscent of Rumplestiltskin) scares readers in 'Rupert, the Knight and the Lady' (1925), until he is killed by a knight. Tourtel's stories became even darker when her beloved husband passed away from tuberculosis in a German sanitarium on 6 June 1931. She never got over his death. From that moment on, she constantly wore black and carried his ash with her wherever she went. She continued 'Rupert' for five more years, but clearly lost her spark. Readers complained that the stories became too frightening and depressing for children. In 1932 Tourtel had Rupert and his friend Margot kidnapped by bandits who left a ransom note. She was directly inspired by the real life-kidnapping of aviator Charles Lindbergh's baby son, who was later found dead.

'Rupert Bear' - 'Rupert and the Magic Toyman' - The Daily Express, 28 September 1922.

Recognition

For her book illustrations, Mary Tourtel won the National Book Prize (1893), Princess of Wales Scholarship (1894), the Owen Jones Medal (1888) and the Rosa Bonheur Prize (1900). In 2003 the Canterbury Heritage Museum opened a special section devoted to Rupert Bear. On 3 September 2020 the Royal Mail issued an official set of stamps to celebrate Rupert's 100th birthday.

Retirement and death

On 28 June 1935, Mary Tourtel passed 'Rupert' on to Alfred Bestall. She was not only tired of the series, but also suffered from failing eyesight. In the previous years, the paper had accommodated her by alternating new 'Rupert' stories with reprints of older ones. The Daily Express gave Tourtel a "golden handshake" plus the copyrights of her stories, which she sold to the publishing house Sampson Low Ltd. This enabled her to live a comfortable retirement. At first she moved in at her brother's home, but eventually spent her final years wandering around, spending nights in hotels, just like when her husband was still alive. In interviews, Tourtel expressed regret over having created 'Rupert Bear'. Her creator backlash might be explained by the fact that she sacrificed her promising career as a children's book illustrator in favor of this comic strip. Particularly from the late 1920s on, 'Rupert' became a full-time occupation. In 1948 she suffered a brain tumor and collapsed. Tourtel was rushed to the hospital, but nevertheless passed away in Canterbury on 15 March 1948, at age 74. Some sources claim she died a week after her collapse, others say she passed away in the hospital the very same day.

'The Adventures of Rupert, The Little Lost Bear', by Mary Tourtel - the first Rupert Bear book, published 1921 by Thomas Nelson & Sons.

(Courtesy of Hamer 20th Century Books, Worksop).

Success

Right from the start, 'Rupert Bear' was a smash success. In 1921 the first compilation book was published by Thomas Nelson: 'The Adventures of The Little Lost Bear', followed by three more titles: 'The Little Bear and the Fairy Child', 'Margot the Midget & Little Bear's Christmas' and 'The Little Bear and the Ogres' (all from 1922). Sampson Low launched the 'Rupert Little Bear Adventures' in 1924, followed by 'The Little Bear Series' in 1928. The character made regular appearances in The Daily Express' 'Children's Annual' and its short-lived supplement The Daily Express Children's Own (with a completely off-model Rupert drawn by Wasdale Brown). In 1932 an official fanclub was established: the Rupert League. At one point, the staff spent 3,000 pounds a week just to reply to children's letters! Various merchandising products were launched, including - of course - teddy bears. The long-running Rupert Annuals only became a Christmas tradition in 1936, a year after Tourtel retired.

During World War II, the British government subsidized the continuation of 'Rupert' in the Daily Express "for the sake of public morale". Despite budget concerns and paper shortage, the Rupert Annuals appeared in full color from 1940 on. Chief editor Lord Beaverbook even obtained paper supplies so that new annuals could be distributed throughout the war. Nevertheless, 'Rupert' was reduced to only one panel a day. Only after peace returned did the original stories return in full swing.

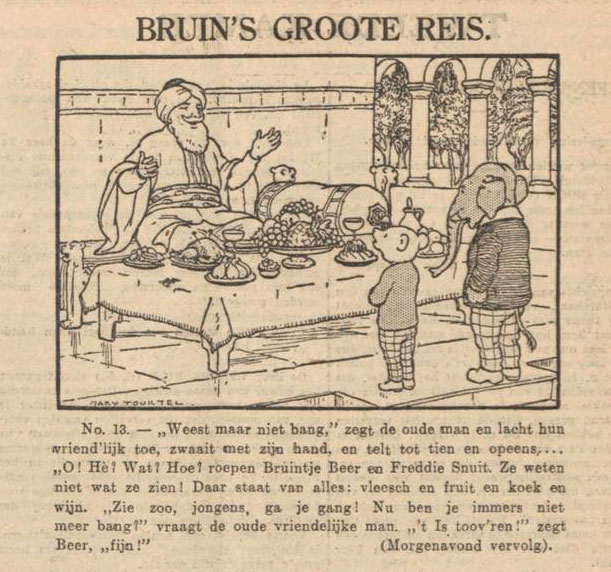

'Bruintje Beer', Dutch-language version of 'Rupert Bear', from Algemeen Handelsblad, 18 December 1929.

Translations

From the 1920s on, 'Rupert' was published all over the British Empire and their dominions. The bear also ran in other languages: Dutch ('Bruintje Beer'), French ('Rupert l'Ours'), Portuguese ('Rupert, o Urso'), Norwegian ('Rupert Bjørn'), Swedish ('Olle Brum', where it originally ran in Dagens Nyheter) and Finnish ('Roope-karhu'). Especially in the Netherlands, it was extraordinarily popular. On 5 November 1929, the series first appeared in the newspaper Algemeen Handelsblad. Since 'Rupert' was originally published in black-and-white, Dutch translators simply named him 'Bruintje Beer' (literally: "Little Brown Bear"). Naturally this caused a glaring error once Rupert was published in color. Yet few readers ever noticed or complained that Bruintje's name didn't match with his white fur color. Therefore his name was never changed, even when other papers ran his adventures. When 'Rupert' was removed from Het Nieuwsblad van het Noorden in 1934, Marten and Jan Gerhard Toonder created a replacement comic about the white polar bear 'Thijs IJs' (1934-1938). Another example of Rupert's lasting popularity with Dutch readers was Phiny Dick and Ton Beek's own text comic about a smart bear, 'Birre Beer' (1954-1959), introduced in Algemeen Handelsblad as "the son of Rupert". Between 1987 and 1990, old 'Rupert' stories by Alfred Bestall ran in the Dutch Disney weekly Donald Duck, adapted by chief editor Thom Roep into the balloon comics format.

Longevity record

After Tourtel's retirement, 'Rupert Bear' was continued by Alfred Bestall from 1935 until 1965. During his era the series achieved its highest popularity and sales. He was assisted by Enid Ash, Alex Cubie and colorist Doris Campbell. After 1965 he was succeeded by Freddie Chaplain (stories) and Alex Cubie in alternation with Jenny Kisler, Lucy Matthews and John Harrold (artwork). Occasional 'Rupert' illustrators were Enid Ash, Wendy Arnot, Kathleen McDougall and Marjorie Owens. From 1985 on John Harrold was the full-time 'Rupert' artist and continued the series until his retirement in 2008. Since then Stuart Trotter has been the main artist.

As of 2023, 'Rupert Bear' has been in constant production for over a complete century, making it with 100 years the longest-running British comic series of all time. Julius Stafford Baker's 'Tiger Tim' (1904-1985) takes second place with an uninterrupted 81 years on its count, while Arthur White's 'Jungle Jinks' (1898-1947) is in third place. Globally, 'Rupert' is also among the record holders. After Rudolph Dirks' 'The Katzenjammer Kids' (1897-2006), Frank King's 'Gasoline Alley' (1918-present) and Billy DeBeck's 'Barney Google & Snuffy Smith' (1919-present), it takes the fourth place as the longest-running uninterrupted comic series of all time. 'Rupert Bear' can additionally claim to be the longest-running text comic, children's comic and funny animal comic in the world. Though, like all newspaper comics, there have been days when reprints were published. Still, only three times over a course of a century has the Daily Express interrupted a 'Rupert' publication, namely to make room for one of Winston Churchill's wartime speeches during the early 1940s and because of the deaths of pope John XXIII (1962) and John F. Kennedy (1963). In 2001 the Daily Express was sold to new owners. Since then there have been no new Rupert stories in the paper, only reprints of earlier stories. The Annuals however still contain new material.

'Rupert and Bill's Aeroplane Adventure' (1933).

Media adaptations

In 1923, 'Rupert' was adapted into a theatrical play titled 'Rupert's Revenge'. Decades later, ITV produced a live-action puppet TV series, 'The Adventures of Rupert Bear' (1970-1977). The theme music was sung by Irish singer Jackie Lee, who also released it as a single. However, the lyrics referred to 'Rupert the Bear', which made generations of people incorrectly add a "the" to the character's name. Interestingly enough, in 1971 the song was also covered in Finnish by Arto Sotavalta. Geoff Dunbar directed an animated short, 'Rupert and the Frog Song' (1984), which won a BAFTA for Best Animated Short Film. In 1985 the BBC presented a TV show where Ray Brooks narrated 'Rupert' stories, while stills from the comics were shown. Nelvana co-produced an animated TV series, 'Rupert' (1991-1997), with Ellipse Programmé, TVS and Scottish Television. A decade later, a CGI/stop-motion series, 'Rupert Bear, Follow the Magic' (2006-2008) was made, produced by Entertainment Rights and Cosgrove Hall Films.

Celebrity fans

The most famous 'Rupert' fan is former Beatle Paul McCartney. He enjoyed the stories as a child, but rediscovered them when he read them to his own children. In 1969, while The Beatles disbanded, he bought the film rights to 'Rupert'. In his 1973 song 'Band On The Run', he namedropped Rupert character Sailor Sam. Decades later the musician was interviewed in the Channel 4 documentary 'The Rupert Bear Story' (1982), which vastly increased Rupert's adult fanbase. The documentary was directed and hosted by another celebrity fan: Monty Python member Terry Jones. A year later, an official fan club was established, The Followers of Rupert, who organize annual "Fun Days" and release associated merchandise. McCartney and Jones were members from the start. Other famous 'Rupert' fans are radio host Mark Radcliffe, architects Richard Rodgers (famous for the Centre Pompidou) and Hugh Casson, actor Terence Stamp and Prince Charles (later Charles III). McCartney not only produced the animated short 'Rupert and the Frog Song', he also voiced Rupert and some other characters, while writing the title song and hit song 'We All Stand Together' for the picture. The former Beatle also wrote the foreword to Caroline G. Bott's biography 'The Life and Works of Alfred Bestall' (2003).

Parodies

In 1971 Jim Anderson, Felix Dennis and Richard Neville, editors of the underground magazine Oz, were sued over an obscene parody of 'Rupert'. The comic in question showed the innocent bear raping an unconscious virgin. It was actually more collage than an actual comic: drawn, cut-and-pasted together by a 15-year old schoolboy, Vivian Berger, who used an 'Eggs Ackley' story by Robert Crumb to make his offensive new creation. Anderson, Dennis and Neveille were charged with conspiring "to corrupt the morals of young children and other young persons". They had to pay a fine and were sentenced to 15 months in jail. The verdict was later squashed on appeal. During the same decade, editorial cartoonist Carl Giles started rebelling against the conservative ideology of the Daily Express, a paper he worked for, by hiding images of Rupert Bear being tortured or killed in his cartoons.

Legacy and influence

Mary Tourtel is generally respected for creating 'Rupert Bear', a character which enjoyed a remarkable longevity and is still recognizable to many people, especially in the United Kingdom. Her 85 stories are praised for their decent artwork and suspenseful, sometimes dark fantasy stories. She can additionally be credited with paving the way for all 'Rupert' artists who came after her. Yet her achievements are generally overshadowed by her direct successor Alfred Bestall, whom many fans regard as the superior writer and artist. While her artwork is top notch, her characters tend to look a bit stiff with little variation in expression. Additionally, her lay-outs are rather monotone with little change in perspective. Tourtel's stories are generally devoid of much humor. In her work, Rupert is often a passive observer, who usually has to be rescued by others. Tourtel also had a tendency to use magic as an easy way to write herself out of narrative corners. In fact, this was one of the first things Bestall was asked to tone down. Last but not least, Bestall's comics have been reprinted far more often than Tourtel's.

While he wasn't the first fictional bear created by British writers and artists, Rupert is the oldest example still iconic today. He paved the way for other famous English bears, such as A.A Milne and E.H. Shepard's 'Winnie-the-Pooh' (1926), Dudley D. Watkins' 'Biffo' (1948), Harry Corbett's 'Sooty' (1948) and Michael Bond and Peggy Fortnum's 'Paddington' (1958). 'Rupert Bear' also influenced Dutch authors like Marten Toonder, Phiny Dick, Thé Tjong-Khing, Piet Wijn and Thom Roep. Particularly Toonder's comics reveal Tourtel and Bestall's influence in every frame. One of his earliest series, 'Thijs IJs' (1934-1938) starred a smart adult polar bear, while his signature series 'Tom Poes en Heer Bommel' (1941-1986) and 'Panda' (1946-1991) also have bears as protagonists. Just like 'Rupert', Toonder's comics are set in an idyllic countryside, where modern and more ancient elements are brought together, just like funny animals and human characters. One particular character, Joachim Sickbock, is a wise goat just like The Old Wise Goat in 'Rupert'.

Books

For those interested in 'Rupert Bear', George Perry and Alfred Bestall's 'Rupert: A Bear's Life' (Pavilion Books, London, 1985) and John Beck and Pamela Stones' 'The Rupert Index - 100 Years of Stories' (2020) are highly recommended.