Urbanus - 'Het Verslechteringsgesticht'.

Willy Linthout is a Belgian comic writer and artist, who had one of the most unusual careers in the history of the medium. He started off drawing parody comics ('De Zeven van Zeveneken', 'Kuifje en de Vervalsers', 1982), before hitting it big with his humorous celebrity comic 'Urbanus' (1982-2022). Based on the popularity of the Flemish comedian Urbanus - who also contributes to the scripts - it initially met with the same prejudice, scorn and derision celebrity comics receive. Downgraded by most adults, it nevertheless gained a cult following among children. Thanks to the comedian's fame in the Netherlands, the comic strip also found a market there. Much was owed to Linthout's imaginative storylines, colorful characters, subversive black comedy and witty pop culture references. 'Urbanus' subverted many expectations. It's the longest-running celebrity comic in the world created by the same writer/artist team. It also managed to outgrow its original source material and become more its own thing. In 2007, Linthout reinvented himself with the dramatic adult graphic novel 'Jaren van de Olifant' ('Years of the Elephant', 2007-2008), which deals with his grief over his son's suicide. Its emotional depth surprised both fans and critics and led to several awards and even foreign translations. He followed it up with a more light-hearted autobiographical graphic novel, 'Wat Wij Moeten Weten' ('What We Should Know', 2011), which explores his family history. His children's family comic 'De Familie Super' was launched in 2022. Linthout also writes scripts for the children's comic series 'Roboboy' (2003, art by Luc Cromheecke) and the police comic 'Het Laatste Station' (2007-2008, art by Erik Wielaert). Throughout his long career, Linthout has often polarized readers and critics, but managed to surprise many with his staying power, versatility and inventiveness.

Early life

Willy Linthout was born on 1 May 1953 in Eksaarde, but his parents registered his birth one day earlier to receive an extra month of child support. They needed the money, because they were florists who didn't earn much. Linthout grew up in a relatively poor family where his favorite pastime was doodling and reading comics. Since his family couldn't afford drawing paper, he usually scribbled in the margins of used newspapers, preferably Het Volk - which had the biggest ones. He once managed to sell these "mini comics" to a girl in his neighborhood, but her parents forced her to ask for her money back. As a child, Linthout had a knack for scribbling inside other people's property. When he had to spend some time in a hospital, a neighborhood kid lent him some 'Suske en Wiske' comics by Willy Vandersteen. He actually wanted Mickey Mouse comics, so he drew Mickey ears on all the characters. When the books were returned, his friend beat him up for it. As an acolyte in his local church, Linthout got in trouble a second time. He had scribbled inside an ancient 15th-century missal, for which he was locked up inside a coal hole as punishment - only to draw on the walls instead.

Linthout has always been a huge comics fan. Among his graphic influences were Walt Disney/Floyd Gottfredson's 'Mickey Mouse', Willy Vandersteen's 'Suske en Wiske', Les Barton's 'Billy Bunter', Rudolph Dirks/Harold Knerr's 'Katzenjammer Kids' and particularly the madcap comedy of Marc Sleen's 'Nero', 'Piet Fluwijn en Bolleke' and 'De Lustige Kapoentjes'. As a teenager, he discovered underground comix and gained love for Robert Crumb and Gilbert Shelton. Later in life, Linthout also expressed admiration for Piet Tibos, Jack Cole, Harvey Kurtzman, C.W. Kahles, Grant Morrison, Richard Corben, Jordi Bernet, Paul Pope, Rob G., Henk Kuijpers, Eric Schreurs, Hanco Kolk, François Boucq, Olivier Schwartz, Hiroki Endo, Marten Toonder, Alan Moore and Matt Groening. He remained a passionate collector of comics and associated merchandising. In the 32nd issue of Kuifje in 1983, his self-created three-dimensional clay Tintin figurines were even the subject of an article.

Early comics

At age 14, Linthout published his first comics in his high school paper Contactlens at the St. Laurentius Institute in Lokeren. 'Prosperken' starred a young adult, named after the street his school was located in, the Prosper Thuysbaertlaan. In 2014, Linthout fan Gerry Van Laer managed to obtain these comics with permission of the school's principal. They already show jokes and side characters - like a sadistic teacher and corrupt priest - which would later be reused in 'Urbanus'. As a teenager, Linthout sometimes signed with his real name, but also used the pseudonym "Willy Ribbonwood", a literal English translation of his last name. On 16 October 1968, a gag comic by the 15-year old Linthout, depicting characters from Jef Nys 'Jommeke', was published in issue #41 of 't Kapoentje. This was consequently also his first parody comic in print. After leaving school, Linthout became a metal turner in a factory. In his spare time, he made several comics published in limited editions. His first book, 'Waarom? En Andere Vreemde Verhalen' (1977) was a collection of short comics stories by himself and his brother Antoine. By selling waffles he was able to pay for the printing. Between 1976 and 1979, he also saw three of his comic strips published in the readers' section 'Plant 'n Knol' in Robbedoes.

'De Zeven van Zeveneken', starring Nero, Matsuoka, Meneer & Madam Pheip and Beo the mynah bird. The ghost in the fifth panel is a reference to Jef the World Conscience from the 'Nero' story 'De Pax Apostel' (1958).

De Zeven van Zeveneken

In 1982, Linthout published his first complete comic book adventure: 'De Zeven van Zeveneken' (1982) under the pseudonym Rib. The work is a pastiche of Marc Sleen's 'Nero', more specifically the black-and-white stories from the early 1950s. It follows the same nonsensical narratives and various characters from Sleen's comics have a cameo. Even Sleen himself is visited by Nero halfway through the story, whereupon he complains that "his hero looks so strange that he is probably drawn by an imposter." In reality, Linthout had asked Sleen for official permission. 'De Zeven van Zeveneken' is a labor of love which mimics Sleen's style neatly. Linthout showed off his knowledge by even referencing the very obscure 'Nero' story 'De Geschiedenis van Sleenovia' (drawn by Willy Vandersteen and Eduard De Rop, 1965) and basically the first official parody of the series.

'De Zeven van Zeveneken' appeared in a limited edition of about 100 copies. Much to Linthout and Sleen's chagrin, bootleg editions popped up, exceeding over 1,000 copies. It remained an extremely rare publication until a 2025 reprint was released. In fact, it took until 2017 before a new complete and official 'Nero' parody was published: Kim Duchateau's 'De Zeven Vloeken'. Three years later, Linthout wrote a second official 'Nero' story, 'De Toet van Tut' (2020), illustrated by Luc Cromheecke and again prepublished in Knack.

Eppo and Wordt Vervolgd

In 1981, Linthout was one of the winners of a scriptwriting contest organized by the Dutch Eppo magazine. His 'Eppo' gag was eventually drawn by Uco Egmond and published in Eppo #6 of 1981. Two years later, Linthout was one of three winners of a reader's drawing contest by Dutch comic magazine Wordt Vervolgd. As part of the prize, his winning comic strip 'Wooden Heart' appeared in issue #26 (January 1983), making this his professional debut in a magazine. In issue #31 (June 1983), his one-shot gag 'De Seksmaniak' was published, followed by the gag 'Hypnose' in the next issue, #32 (July/August 1983). In 1993-1994, Linthout returned to magazine work, when he made weekly tv-related cartoons for TV-Express.

'Kuifje en de Vervalsers'.

Kuifje en de Vervalsers

In 1983, Linthout made another comics spoof: 'Kuifje en de Vervalsers' (Vive La Suisse, 1983), lampooning Hergé's 'Tintin'. The story was unusual, because it also parodied another parody comic, namely Filip Denis' infamous Tintin porn spoof 'Tintin en Suisse' ('Tintin in Switzerland', 1976). Back in the day, 'Tintin en Suisse' made headlines because Hergé's estate banned it both in Belgium and France. In Linthout's story, Hergé is outraged over Tintin's sexual escapades in Switzerland, though it turns out there is a doppelganger, Oskar, at work. The real Tintin therefore tries to hunt down this lewd imposter. He drags him to the Swiss court, asking the judge to let Oskar "pay him in damage for every dick he drew in the story". Oskar, however, flees to the Netherlands, where the entire case is dismissed.

Contrary to his previous parody, Linthout didn't ask Hergé's heirs for permission, because his story spoofed Filip Denis more than the original 'Tintin' stories. Nevertheless, he still put a lot of effort in mimicking Hergé's "Clear Line" art style, proving that he is a much better artist than some people give him credit for. 'Kuifje en de Vervalsers' never received a reprint and didn't sell well either. It remains the most obscure title in Linthout's catalog, also because he took the precaution of leaving the entire album unsigned.

First two panels of 'Het Fritkotmysterie' (colorized version).

Urbanus

Now that Linthout had proven himself capable of completing two comic albums within two years, he wanted to create his own series. In 'De Zeven van Zeveneken', he had given popular Flemish comedian and singer Urbanus a small cameo. He realized that Urbanus had potential as a comic character. After all, his stage persona and comedic style were quite cartoony. Urbanus often went on stage dressed in a Beanie (propellor hat), baggy pants and suspenders. His routines, sketches and songs depicted himself as a bratty manchild and made use of nonsensical black comedy and toilet humor. A comic strip about him would be lucrative too, since he was already famous and popular in Flanders and the Netherlands, especially among children. Linthout therefore asked Urbanus for official permission and took a copy of 'De Zeven van Zeveneken' with him. Since the comedian was a fan and personal friend of Marc Sleen, the deal was instantly sealed. On 10 November 1982, the first story, 'Het Fritkotmysterie', was serialized in the Flemish teen weekly Joepie.

Urbanus: success and longevity

Like many comics based on a popular media star, 'Urbanus' met with instant scorn and derision, increased by the fact that some adults disliked the comedian over his vulgar and blasphemous jokes. Yet contrary to many people's expectations, 'Urbanus' lasted much longer than only two albums. The debut album alone sold 50,000 copies from the start. The comic strip later ran in the TV weeklies Dag Allemaal, Panorama/De Post, TV Express and the newspaper Het Laatste Nieuws. By the time the last album rolled from the presses in 2022, 201 titles had been made, making it the longest-running Belgian celebrity comic and the longest-running Dutch-language celebrity comic (with Wim T. Schippers and Theo van den Boogaard's 'Sjef van Oekel' at second place and Hec Leemans' 'F.C. De Kampioenen' in third.). The longest-running celebrity comics in the world are arguably the ones based on comedy duo Laurel & Hardy and those starring Mexican wrestler El Santo. But these were drawn by dozens of different artists for different companies, often without each other's knowledge. 'Urbanus', on the other hand, is the longest-running celebrity comic in the world by one and the same team, lasting 40 years non-stop.

The secret of its success can be attributed to several factors. First of all, for over half a century, Urbanus has rarely been out of the public eye, making new shows, tours, movies, records and/or guest appearances every year. It helped him stay recognizable to new generations of readers. His media projects indirectly promoted the comic and vice versa. Secondly, Urbanus had a gift for self-mockery. He didn't mind that Linthout put him in many embarrassing and painful situations, something more self-important media stars would never stand for. This offered the cartoonist tremendous limitless creative possibilities, which kept the series fresh and daring.

Cover illustration for album 29, 'De Slavin van Tollembeek'.

Originally, Linthout wrote and drew 'Urbanus' on his own, but after two albums Urbanus felt he ought to keep an eye on all his merchandising items. Other than that, he always dreamed of making his own comic strip and thus couldn't resist joining in the fun. However, their creative partnership has often been misunderstood. First of all, Urbanus doesn't draw the series, though Linthout has credited him with the design of a few side characters. Another misconception is that Linthout merely illustrates Urbanus' scripts. In reality, the comic strip is mostly Linthout's brain product. He created the regular cast, nearly all the side characters, the setting and the stories. Urbanus mostly guards the tone and peppers the script with extra ideas or jokes if a scene requires some. Right from the start many people wondered why Urbanus collaborated with such an amateur cartoonist. The artwork of the early stories looked crude, with little regard for anatomy, perspective or proportion. Yet Urbanus recognized a kindred spirit in Linthout. They both adored black comedy, comics and understood what children enjoy. Most importantly, Linthout's imagination was strong enough that Urbanus didn't have to guide him - a rare gift for celebrity comic artists. This was especially handy given Urbanus' busy schedule, which made it occasionally difficult to organize brainstorm sessions. In the early decades, Linthout sometimes went on tour with Urbanus to discuss new stories in hotel rooms or his car.

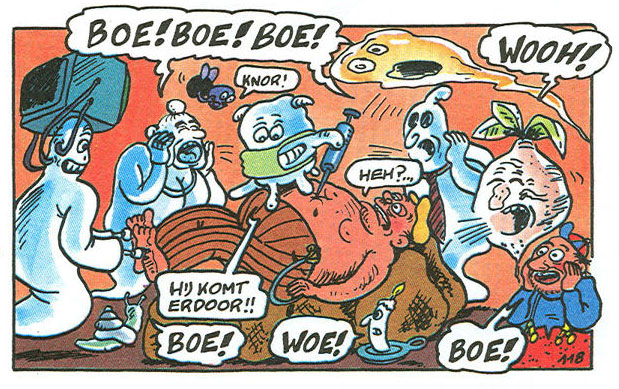

De Avonturen van Urbanus #55 - 'De Geest in de Koffiepot'.

Urbanus: concept and setting

Linthout has always dismissed the stigma "celebrity comic" for 'Urbanus', because his series has very little to do with the real-life comedian. His comic book version indeed looks like him, wears the same stage outfit and - just like the real Urbanus - lives in the town Tollembeek. Over the decades, the comic strip occasionally referenced Urbanus' franchise. Gigippeke van Meulenbeek in 'Het Fritkotmysterie' and the Hittentitten in 'De Hittentitten Zien Het Niet Meer Zitten', for instance, are nods to characters from Urbanus' songs. In 'Urbanellalla' (1989), the town organizes a soundmix contest tribute to Urbanus, where the characters cover actual Urbanus' songs. In '... En Ge Kunt Er Uw Haar Mee Kammen' (1990), Urbanus' half brother Werther is a nod to Urbanus' real-life TV sidekick Werther Van Der Sarren, while one gag in 'Dertig Floppen' (1991) spoofs Urbanus' real-life game show 'Wie Ben Ik?'. His real-life statue is part of the plot of 'Het Bronzen Broekventje' (2000).

Other than these elements, the comic strip takes place in a totally different universe. The comic book Urbanus is not an adult, but a young teenage boy who still lives with his parents. He is a sneaky but sometimes naïve brat. His father, César, is a dumb unemployed farmer, while his wife Eufrazie is a devout Catholic housewife. Their looks were based on Linthout's parents. Urbanus' hometown Tollembeek bears no resemblance to the real-life village either. Some backgrounds are inspired by Linthout's own birth town Eksaarde and neighboring villages. Certain characters were based on friends, relatives and people from Linthout's childhood. The priest, for instance, but also the main antagonist Jef Patat, who is a caricature of Linthout's publisher Jef Meert. In his autobiography, 'En Van Waar Dit Allemaal Komt', Urbanus said that Linthout was frequently criticized by people who thought he made his celebrity comic without Urbanus' knowledge or permission. To prove these people wrong, Urbanus and Linthout made more collective media appearances. On the back cover of each 'Urbanus' album a photo collage was added, visualizing a scene from the story. Urbanus obviously played himself, while Meert performed Jef Patat and Linthout took the role of César. Through this cut-and-paste work of amateur snapshots of Urbanus, sceptics could see for themselves that Urbanus was fully aware and involved. Urbanus also drew the cartoony background art in these collages, colorized by his daughter Liesa.

De Avonturen van Urbanus #72 - 'Vers Gebakken Poetsen'.

Linthout wanted 'Urbanus' to evoke the atmosphere of the comics he grew up with. Every story starts with a typical introduction panel as was common in classic newspaper comics. The characters speak dialect, since most Flemish comics until halfway through the 1960s didn't use standard Dutch. Some words are deliberately old-fashioned, very local dialect words or spelled phonetically. Ironic captions often offer explanations, dedicated "to our readers in The Netherlands." Just like in classic comics, many stories are utterly unrealistic. Characters will craft wacky inventions or ploys, which somehow work. All animals have the ability to speak, like Urbanus' pet pig Wieske, his genius pet fly Amedee and dumb dog Nabuko Donosor, whose upper jaw floats above his lower one. Witches, vampires, extraterrestrials and comic characters from other franchises often pop up for the fun of it. Certain side characters are classic comic book archetypes. Urbanus' rich uncle Nonkel Fillemon comes straight out of Carl Barks' 'Uncle Scrooge' comics. His untrustworthy butler Eugène is an expy of Nestor from Hergé's 'Tintin'.

In school, Urbanus is tormented by a sadistic teacher, Mr. Kweepeer, and an obese, bespectacled pupil, Dikke Herman, both directly inspired by Mr. Quelch and Billy from C.H. Chapman's 'Billy Bunter' (particularly Frank Richards and Les Barton's version). Another pupil is the black kid Botswana, often referred to as "Het Negerken" ("The Little Negro"). The latter spoofs classic characters like Jijé's Cirage and Frans Piët's Sjimmie whose only purpose seemed to be a black stereotype and nothing else. Another pupil, Pinnekeshaar, took his name from the Dutch-language name of the boy Poildur from Franquin's 'Spirou' stories. Dr. Kattenbakvulling (literally "Dr. Kitty Litter") and Dr. Schrikmerg (literally "Dr. Fearmarrow") are typical evil mad scientists. The gangsters Stef, Staf and Stylo are inspired by Morris' The Daltons from 'Lucky Luke'. Last but not least, there is a dumb muscular guy named Birdbrain who wears Mickey Mouse ears and enjoys thinking up words that rhyme with other people's sentences. When he can't think of something, he becomes mad.

De Avonturen van Urbanus #47 - 'De Harem Van Urbanus', featuring an extreme version of a dating show.

Yet Linthout subverts the classic Flemish family comic by adding elements more reminiscent of an underground comic. He and Urbanus deliberately wanted to make a children's comic which sides with the kids, rather than the adults. However, the comedy itself is more adult than child friendly. Urbanus is a bad boy who hates school, plays pranks and lures at naked women. His parents, teachers and local priest Mr. Pastoor often punish him mercilessly. Yet they are no role models either. Father César is an alcoholic, pipe-smoking whoremonger. Mr. Pastoor often swears, boozes and is unconcerned about his celibacy. Urbanus' young and sexy school teacher Juffrouw Pussy is often stripped nude. Jef Patat has a private porn collection. The police officers René and Modest use excessive violence. Even God himself is a recurring character. But he is far from a Supreme Being, acting more like a cranky old man. Many stories are filled with anti-authoritarian comedy, blasphemous jokes, toilet humor, sexual gags and gruesome violence. In 'Het Verslechteringsgesticht' (1989), all kids in Tollembeek suddenly become too nice and obedient for their own good and Urbanus is asked to organize a special school to teach them how to misbehave again. In 'De Depressie van Urbanus' (1993), Urbanus tries to commit suicide to be reunited with his true love in Heaven. When he finds out Heaven doesn't allow suicidal people, he tries to make his suicide look like "an accident", frequently killing innocent bystanders in the process. In 'De Harem van Urbanus' (1994), Urbanus opens a peep show.

In some stories, classic comic characters from other franchises turn up in depraved situations. In 'Dertig Varkensstreken' (1992), Jef Nys' Jommeke appears as a guest star, yet his goody two-shoes behavior is so horrible that Urbanus and his pets start yelling obscenities "to save their series". In 'Game Over' (1995), Urbanus enters Euro Disney with a Mickey Mouse hat, when suddenly his pants drop down, revealing his exposed genitals. All children and parents think he is the real Mickey, whereupon the theme park goes bankrupt.

Willy Linthout has a cameo in album 11, 'De Tenor Van Tollembeek'.

Urbanus: controversy

Because of the subversive comedy and toilet humor, many adults consider 'Urbanus' unsuitable for children. Its very "forbiddenness" is, of course, the prime reason why kids adore it. Many long-time fans have fond childhood memories of reading the series on the sly, chuckling about all the naughty jokes. Linthout and Urbanus knew they had made it when they heard about a boy in boarding school who was punished for having an 'Urbanus' story in his suitcase. Even today, many adults dismiss 'Urbanus' as low-brow entertainment, despite rarely actually having read it.

It should be mentioned that the series has often poked fun at its own reputation. In 'De Tenor van Tollembeek' (1986), Urbanus becomes a pop star and a street artist named "Willy Lintworm" is forced to whip out "badly drawn" celebrity comics about him, the majority plagiarizing classic 'Nero' stories. In 'Aroffnogneu' (1992), Urbanus promises to keep the story free from bathroom comedy, only to give it up halfway through the story. In 'De Vettige Vampiers' (1994), Urbanus wants to know the title of his (then future) "album nr. 75". When a fortune teller informs him that it will be called "The Facelift of Urbanus", Urbanus comments this is a rather uninspired title, which the fortune teller blames on the writers becoming more unoriginal. Funnily enough, album nr. 75 (1999) was indeed given that title, but the writers quickly rushed it out in two panels before making the actual story under a completely different title. The authors mock this by having an old lady who reads the story feel utterly confused.

De Avonturen van Urbanus #36 - 'Aroffnogneu'. Urbanus is asked by his teacher what animal makes the sound: "aroffnogneu"? He answers "a sea elephant" and when his teacher disbelieves him, he runs out to fetch one, which his teacher dismisses as "If you can do that, then I'm an anteater." When Urbanus actually drags one into the classroom, the teacher briefly changes into an anteater by surprise. Still he's not convinced, because the sea elephant ought to be "in heat". Urbanus then asks the sea elephant "to show his rutness."

By challenging taboos and not being bound by restrictions, 'Urbanus' is one of the more unpredictable and experimental Flemish comic series. Linthout hasn't been afraid of killing off major characters from time to time, including the main cast. Many stories feature silly ideas and very imaginative plots. In 'De Kleine Tiran' (1987), Tollembeek becomes a mini monarchy where Urbanus rigs the elections to become their local tyrant. Urbanus gets the Book of Creation in his possession in 'De Zeven Plagen' (1990), whereupon God sends down seven plagues to Earth (not the same as in the Bible, far wackier ones!) to force him to give the book back. Urbanus has to memorize the content of six door stopper novels in 'De Zes Turven' (1991) to inherit a fortune, yet tries to cheat in every possible way. In 'Aroffnogneu', Urbanus has to describe in class what kind of animal makes the sound "aroffnogneu", whereupon he runs out to fetch a sea elephant "whom he noticed waiting at the bus stop, a couple of blocks away." The town council in 'Leute voor de Meute' (1993), decides to execute Urbanus in a big-budget spectacle, parodying bread and circuses. 'De Vettige Vampiers' (1994), stars vampires who suck people's body fat, rather than blood. In 'De Laatste Hollander' (2001), the cast visits the Netherlands until the entire county is vaporized by extraterrestrials, leaving only one Dutchman - a man of Surinamian descent - behind. Mr. Pastoor becomes the victim of accusations of child molestation in 'Pedo-Alarm' (2011), whereupon he is arrested and Urbanus sent to a help center.

Stories often break the fourth wall. In 'De Kleine Tiran', the creators decided to end the story one panel early, because they are "confused about their own plot". In 'De Sponskesrace' (1989), the narrative continues on the cardboard book cover. 'De Hete Urbanus' (1995) is a complete photo comic, 'De 3D-bielen' (2008) entirely made in 3-D, while 'Het Zwarte Winkeltje' (1996), self-described as "the first interactive comic" features four different storylines spread over four different strips, which the reader can follow by choice.

Urbanus 87 - 'De Wraak Van Boemlala'.

Certain 'Urbanus' stories feature clever satire of real-life TV shows, films, toys, comics and celebrities like the Belgian royal couple, President Ronald Reagan, the Pope, Queen Beatrix of the Netherlands, Michael Jackson and Flemish schlager singer Eddy Wally. In 'Een Knap Zwartje Is Ook Niet Mis' (1994), Urbanus, his parents and pets all find success in their own different endeavors. Urbanus decides to change their look and borrows a facial cream suggested to them by Michael Jackson's monkey "to give them a nice tan". Unwillingly, their skin color turns black and suddenly they become victims of racism. The same people who were once so enthusiastic about their achievements suddenly feel they can't make business deals "with black people".

On 26 October 2022, the 201th and final 'Urbanus' story, 'Het Allerlaatste Avontuur', was published, marking the end of the series after 40 years. Urbanus and Linthout admitted that sales weren't what they used to be. Both also wanted to move on to other projects. On 16 April 2026, a new 'Urbanus' story, 'Het Vergeten Avontuur', was released, officially to honor Urbanus final comedy theatre tour, but also because Linthout still had inspiration and the urge to create a definitive, ultimate final adventure.

Assistance

During the 1980s, Linthout worked with an assistant, Luk Moerman. In the past, Kris De Saeger was inker on 'Urbanus'. Since 1997, Steven De Rie is Linthout's main assistant, mostly devoted to inking. Hannelore van Tieghem, Sabine De Meyer (wife of Luc Cromheecke) and Vera Claus (wife of Dirk Stallaert) have been the series' colorists. Since the late 2010s until the final album in 2022, Ann Smet has been co-scriptwriter of the series, alongside Urbanus and Linthout. She is credited with inventing a running gag, starring a Japanese Maneki Neko cat sculpture who counts down until the final panel.

Introduction panel for Urbanus #177 - 'De Levende Blokjes'.

Publishing company Loempia

On 16 December 1983, Linthout and his friend Jef Meert established their own publishing company, Loempia. For almost a decade and a half, Loempia thrived mostly on the success of the 'Urbanus' stories, though they also distributed similar subversive and/or celebrity comics by artists like Lukas Moerman ('De Papevreters'), Kamagurka and Herr Seele ('Lava', 'Cowboy Henk'), Erik Meynen ('Jean-Pierre Van Rossem'), Auke Herrema ('Een Kleine Verbouwing'), Yurg & Tony Beirens ('Wendy van Wanten'), Gummbah and Jan Bucquoy. In collaboration with French publisher Magic Strip, Loempia also published French-language comics by Frédéric Boilet, Ataide Braz, Yves Chaland, André Franquin, Bruno Goossens, Jacques Laudy, Bruno Loisel, Jacques Martin, Hector G. Oesterheld and Hugo Pratt, Roberto Raviola, Jacques Tardi and Daniel Torres. Under the subdivisions "Turbo" and "Follies", they released erotic comics by Paul Cuvelier, Guido Crepax, Milo Manara, Paolo Euleteri Serpieri, Eric Stanton, Zefiro and Charlie Hebdo writer Professeur Choron. Despite Loempia's success, Meert eventually sold the company in 1996 to Standaard Uitgeverij, allowing serialization of 'Urbanus' in their newspapers De Standaard en Het Nieuwsblad.

An attempt was made to translate 'Urbanus' in French too (as 'Urbain'), but it didn't catch on. 'Urbanus' also had a cameo appearance on page 60-63 of Alan Moore's 'Portrait of an Extraordinary Gentleman' (2003), in a gag comic drawn by Linthout and De Rie under the title 'Urbanus Gets... Much Moore Than He Asked For' (2003).

'Urbanus Gets... Much Moore Than He Asked For' (2003). In this panel, Urbanus accidentally murders Rorschach from Alan Moore's 'Watchmen' comics.

Merchandising

Apart from streamlining the 'Urbanus' comics, Loempia (and later Standaard Uitgeverij) also took care of merchandising products, such as key chains, puzzles, CD-roms, jeans, boxer shorts, craft-, game- and coloring books. All products were kept under tight quality control, making sure that they were in line with the tone of the comics. Their game books, for instance, weren't comparable to a regular children's game book. All games featured silly solutions and unexpected twists. In 1988, Linthout and Urbanus made a special advertising comic for shoe company Brantano, titled 'Urbanus Maakt Reclame' (1988), but satirized the very brand they were promoting. In the story, a desperate shoe salesman tries to exploit Urbanus into selling his product, but the boy is too stupid to understand his marketing strategies. The comic book was later added to the regular 'Urbanus' series, but changed Brantano into a fictional shoe brand.

With 'Urbanus In De Hoek' (1989), Linthout and Urbanus brought out a so-called moralistic book to raise obedient children, which in reality was quite the opposite. For the drug information telephone service De Druglijn, Linthout drew the one-page gag comic 'Urbanus Tegen De Drugbaron' (2004) in which Urbanus fights off a drug baron in an airplane. In March 2011, the special Cesar Tripel beer was named after Urbanus' father in the comics. The logo was designed by Linthout. A theatrical musical about the comic strip was announced for the fall of 2020, directed by Stany Crets and produced by Deep Bridge. However, the COVID-19 pandemic canceled those plans.

'Urbanus Maakt Reclame'. In the original version Urbanus advertised for real-life shoe brand Brantano. This was changed to a fictional shoe brand when this exclusive comic was added to the official 'Urbanus' series.

Animated adaptations

In 1992, Urbanus also went into animation. With the support of FOX, the album 'Het Lustige Kapoentje' was adapted into a 25-minute animated short. Linthout remembered that the people at FOX didn't really understand Urbanus, being utterly confused that the character was a child with a beard. They also felt the comic strip resembled Matt Groening's 'The Simpsons', both in terms of subversive comedy and using a city as setting. Naturally, 'Urbanus' was much older than the yellow-skinned family, but Linthout took it as a compliment. 'Het Lustige Kapoentje' was made available on home video, but nevertheless didn't sell well. In the United States, it also circulated as a bootleg video named 'The Cheerful Rascal', despite the fact that nobody there was familiar with the original comic.

Between 1 September and 13 October 1999, to celebrate Urbanus' 50th birthday, a weekly TV series, 'Eindelijk 50!', was broadcast on the Dutch public TV channel VRT. It showed archive footage of Urbanus' old shows and TV sketches, alongside never-before released material. Naturally, the birthday boy himself hosted the show. The opening credits featured an animated short based on Urbanus' drawings, while other animated quickies were adaptations of gags from Linthout's 'Urbanus' comic. On 27 February 2019 an animated feature film, 'Urbanus, de Vuilnisheld', was released, produced by Eyeworks. Keeping in tone with the comics' subversive and vulgarities, it appealed to kids and left adults a bit uncomfortable, but nevertheless did well in theaters. Interestingly enough, black side character Het Negerken was remodeled.

Covers of the 'Roboboy' albums number 2 and 5, artwork by Luc Cromheecke.

Roboboy

Linthout has also written scripts for other artists. Together with Luc Cromheecke, he created the funny children's comic 'Roboboy' (2002-2009), not to be confused with Jan van Rijsselberge's animated TV character 'Robotboy' (2005-2008). Roboboy is a little extraterrestrial robot from the planet Kryptobot. After a nuclear explosion, he fell on Earth, where he is adopted by Mr. and Mrs. Kwabbelmans, a childless couple who also own a dog named Kastaar. Roboboy has trouble adapting to his new environment and vice versa. Many people find him strange, because he is not a "real" boy. He drinks oil and has numerous unusual gadgets hidden inside his suit. Some people dislike him, while others just misunderstand his good intentions. Yet he often manages to surprise them and subvert their prejudices. The charmingly innocent stories surprised some adults who previously associated Linthout with the depravity of 'Urbanus'. Many children's magazines ran 'Roboboy', among them Taptoe, Spirou and - under the different title 'Supersnotneus' - in Suske en Wiske Weekblad too. In fact, it won Linthout the first awards in his career. At the 2003 Prix Saint-Michel Festival in Brussels he received the award for "Best Dutch-language author" and "Best Dutch-language children's author". 'Roboboy' also won "Best Dutch-language Children's Album" during the 2003 Stripdagen in Alphen aan den Rijn.

Personal dramas

In 2004, Linthout was struck by severe sleep apnea, which forced him to wear tubes and a facial mask with positive airway pressure. Worried about his health, the artist was hit by even more tragic news that same year: his only son Sam committed suicide by lying down on a railroad track. He was only 21 years old. Overwhelmed with grief, Linthout has trouble carrying on and even considered quitting 'Urbanus' altogether. But he remembered that his son once said that it was his duty to continue the comic series since so many children enjoyed it. This convinced him to continue and he actually found escapism in it too. Still, Linthout wanted to express his emotions in one way or another. As he was already writing the script for a new comic series, 'Het Laatste Station', he altered the story somewhat to reflect his mourning.

'Het Laatste Station', artwork by Erik Wielaert.

Het Laatste Station

Between September 2007 and 2008, Standaard Uitgeverij released three albums of 'Het Laatste Station' (2007-2008), written by Linthout and illustrated by Erik Wielaert. Inspector Vandermeulen is a police inspector down on bad luck. He and his colleagues don't get along, his car breaks down and his mother, whose husband died, lives in a retirement home where she can't cope with her grief. Vandermeulen tries to find a mysterious serial killer who calls himself "the Monk" and who conducts a killing spree in the red light district. After a while, he realizes he has become a personal target too. The series spawned three titles. 'Het Laatste Station' was Linthout's first attempt at an adult drama and was written with assistance from his brother Theo. Linthout added the subplot about Vandermeulen's father's suicide, mirroring his own son's suicide. At the time, this heavy theme needed to be a bit distant from Linthout's own personal tragedy, which explains why he made the victim a father rather than a son. Yet he realized he wanted to confront his grief in a more direct and personal comic strip.

Jaren van de Olifant / Years of the Elephant

For two years, Linthout worked on his monumental eight-part graphic novel series 'Jaren van de Olifant' ('Years of the Elephant'). The work was first released by Bries as eight comic books under the title 'Het Jaar van de Olifant' (2007-2008), and then collected in one volume as 'Jaren van de Olifant' (2009) by Meulenhoff/Manteau. An updated edition with two new chapters was released by Davidsfonds in 2022.

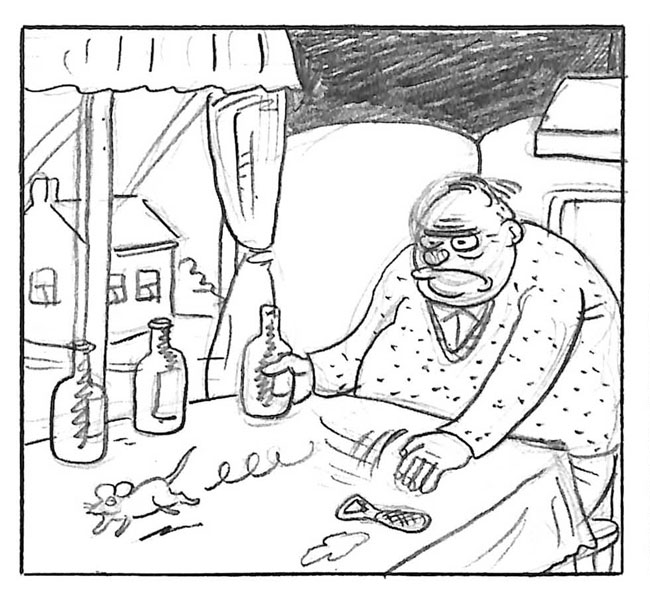

The title refers to the facial mask and tubes Linthout had to wear because of his sleep apnea, which made his wife compare him to "an elephant". To Linthout, the sleep apnea treatment and his son's suicide were two equally stressful and depressing events in one and the same year, which he dubbed his "year of the elephant." The series revolves around a father (Karel Germonprez), whose son Wannes committed suicide. He goes through a long mourning process where he tries to make sense of the events, all while coping with people's vastly different reactions. His boss, for instance, is cold and distant, while Karel's secretary reacts overly melodramatically. Karel's wife's face is never shown, but a literal cliff between them symbolizes their emotional distance. His late son, represented by a chalkboard line character, frequently haunts him. To keep some emotional distance, Linthout changed some events in his otherwise autobiographical account. For instance, Karel's son died by jumping off a roof. In volume 5, Karel travels by train when the ride is suddenly delayed because a boy had thrown himself in front of the tracks. Much to his shock, other passengers joke or vent their anger about this interruption. Linthout actually went through the same ordeal, only a few months after his son had died the same way. He was so hurt over this event that he drank his sorrows away later that night. The next day, Linthout went to a doctor and found out he suffered from sciatica too. Some events in 'Years of the Elephant' are based on anecdotes from friends, relatives and other people Linthout knew who went through similar experiences.

It took Linthout several years to work on the project. Sometimes he cried while drawing, though not with the explicit emotional scenes, more with tiny details which directly referenced his personal tragedy. In an interview with Humo (2 November 2009), conducted by Diederik Van den Abeele, Linthout revealed that he actually went to lie down on a railroad track, just to experience what his son might have felt. He lay there for a few minutes, until he heard a train coming and quickly got up again. 'Years of the Elephant' was also co-written by Linthout's brother Theo, while Steven De Rie did the lettering and Serge Baeken provided the design.

The series was a remarkable break in style, contemplating life and death, sorrow and grief, all very heavy themes for a cartoonist known as a humorist. Suicide in particular is still a taboo topic, especially in a comic book. Nobody expected he would be able to pull it all off. Some people suggested using a different, more realistic illustrator to match the comic's serious mood. But Linthout felt it was his story, so he didn't care whether his own cartoony style was "fitting" or not. He knew people would always be prejudiced about it. Fans of 'Urbanus' might not be interested in such a dramatic story. Other people might dismiss it merely because he was the creator of 'Urbanus', but he didn't care. The only precaution he took was not inking, nor colorizing his pencil drawings, to keep it different from his more comedic work. The sketchy, black-and-white style gives everything a sad, raw and hermetic feel. Linthout felt it was symbolic of his son's unfinished life. In the end he just wanted to tell his personal story, regardless whether it would sell or be appreciated. All earnings of 'Years of the Elephant' were donated to 'Shangrila Home', an orphanage for street children in Kathmandu, Nepal. Linthout's wife often visits the place. One of the rooms there has been named after their late son, as a sign of gratitude.

However, 'Years of the Elephant' moved many readers and won critical acclaim. Several critics - outside the comic world too - listed it as one of the best books of the year. It won the Dutch Stripschapspenning for Best Literary Comic (2007), the Cultural Award of the Flemish Community (2008) and the Carolus Quintus Prijs for "Most Socially Relevant Comic" (2009). In 2009, he received the prestigious Flemish comics award the Bronzen Adhemar. Even more astonishing was the fact that his graphic novel was translated into English, French, Spanish and Arabic! In 2008, it was nominated for the Prix Saint-Michel for Best Dutch language comic and two Eisner Awards, namely "Best U.S. Edition of International Material" and "Best Writer/Artist Nonfiction". The work is also discussed in Elisabeth El Refaie's 'Autobiographical Comics: Life Writing in Pictures' (2012). Many therapists started using 'Years of the Elephant' to help people coping with similar deaths of friends and relatives.

Linthout was overwhelmed. The literary acclaim and prestige that had eluded him for more than three and a half decades, suddenly fell into his lap. His comics were now read in non-Dutch language countries too. While he was glad that 'Years of the Elephant' was appreciated, he had somewhat mixed feelings about its success. In Flanders, there were still critics prejudiced to dislike his work, because of his association with 'Urbanus'. He observed that in other countries, where 'Urbanus' was unknown, the reception was far more positive, since they misinterpreted 'Years of the Elephant' as his debut novel. After decades of scorn, it was somewhat sad that a comic book about a personal tragedy changed public opinion so drastically. He was very reluctant to go to book signings and/or accept awards either. But it did motivate him to make more autobiographical comics.

The first two chapters of a follow-up to 'Years of the Elephant', called 'De Leveling', were published by Catullus in 2010. It also starred Karel Germonprez, but this time Linthout's own grief is not the theme, but the true story of a mother who lost her handicapped child.

Wat Wij Moeten Weten

Linthout always wanted to write something about his family and found a perfect source. His mother kept a little notebook, titled 'Wat Wij Moeten Weten' ("What We Should Know"). She intended it as a handy reference guide, despite the fact that it had no register. And this wasn't the only odd thing about it: she wrote down all kinds of recipes (including one for rat poison right next to a cake recipe), how to sow certain vegetables and when discount sales took place in Greece. All this while she never used these recipes, her garden was too small to sow anything and she never left Belgium in her entire life. This peculiar book is a leitmotif throughout Linthout's graphic novel 'Wat Wij Moeten Weten' ("What We Should Know", 2011), again co-written with his brother Theo. The story was first released by De Bezige Bij in two albums, and then in a one-volume graphic novel in 2012.

Linthout re-used his alter ego Karel from 'Jaren van de Olifant', but otherwise all other characters are directly based on his own relatives, such as his alcoholic brothers and his mother's bizarre way of cutting her toenails by stitching a piece of sandpaper to the wall and rubbing her toes over it. Part of the book also deals with his mother's death. All in all, it's an all too recognizable portrait of small-minded village life and people too stuck in their own little world to properly communicate with one another. 'Wat Wij Moeten Weten' was released with similar critical attention and translated too, though some critics felt it was more anecdotal and less focused than 'Years of the Elephant'.

'Wat Wij Moeten Weten'.

De Familie Super

After ending his signature series 'Urbanus' in 2022, Linthout launched a new humor comic, 'De Familie Super'. A mixture between a classic Flemish family strip and a U.S. superhero comic, it revolves around a father, mother and their son and daughter. Like their last name indicates, the Supers all have exceptional powers. Father Jack has sweaty feet with incredible stench and strength. Mother Martine is able to stretch her nose. Son Lewis has spiky hair which can sting like a porcupine. He is also able to fire it at people. Daughter Trezemieke's voice can demolish entire walls, though only when she's angry. Finally, grandfather Pepe Smos has hair over which he has no control. Even the family dog can stretch its body to enormous lengths. The Supers live in a typical Flemish village, Bommerskonten, based on the dialect expression 'Bommerskonten', to describe a "faraway primitive, backwards town". However, their home town is inhabited with all kinds of goofy monsters that they have to defeat. Published by Peter Bonte, 'De Familie Super' is made by the same team who previously made 'Urbanus'. Stories are co-scripted with Ann Smet, while Linthout is assisted on the artwork by Steven De Rie. Sabine De Meyer is the colorist.

Additional collaborations with Ann Smet

The collaboration between Willy Linthout and Ann Smet further extended with another graphic novel, 'Gelukkig Worden in 8½ Stappen' ("Finding Happiness in 8.5 Steps"). Published by Standaard Uitgeverij, this 2023 graphic novel was made in the same pencil style as Linthout's previous excursions into "serious" comics. This book follows the life of Morris, from his birth to his death, and tackles the many life questions and problems that he encounters on his path. Also in 2023, Linthout and Smet co-scripted the gags for 'Rare Vogels', the 315th volume in the classic Flemish 'Jommeke' series, drawn by newcomer Dieter Steenhaut.

Graphic contributions

In 1993, Linthout wrote a tribute to Marc Sleen in the book 'Marc Sleen: Een Uitgave van de Bronzen Adhemar Stichting' (Standaard Uitgeverij, 1993), which also used a page from 'De Zeven van Zeveneken' as an illustration. On 4 December 1996, Linthout and Urbanus published 'Kiekebanus', a crossover album with Merho, author of 'De Kiekeboes'. In the story, Urbanus and the Kiekeboes swap houses. The story was drawn by Linthout and Merho, allowing for a veritable clash of their graphic styles and brand of comedy. The villain in the story is a composite character by both authors. In 2001, Linthout was one of several comic artists to contribute to the crossover album 'Het Geheim van de Kousenband' (2001), which made several series by Standaard Uitgeverij, among them 'Urbanus', appear together in one album, drawn by the respective artists themselves. In 2005, the cast of 'Urbanus' visited the Kiekeboe family again in Merho's one-shot album 'Bij Fanny op Schoot' (2005), where Fanny interviews comic characters from different franchises. The same year, Linthout and Urbanus made a graphic contribution to the book '60 Jaar Suske en Wiske' (2005), which paid homage to Willy Vandersteen's long-running and highly popular comic series 'Suske en Wiske'. The men made two separate graphic tributes to Jef Nys in the homage album 'Jommekes Bij De Vleet' (2010) and two separate homages to Marc Sleen in 'Marc Sleen 90: Liber Amicorum' (2012). Linthout paid graphic tribute to Pom's 'Piet Pienter en Bert Bibber' in 'Kroepie en Boelie Boemboem: Avontuur In De 21ste Eeuw' (2010) and Martin Lodewijk's 'Agent 327' in 'Hulde aan de Jarige' (2019).

De Avonturen van Urbanus #120 - 'Rachidje Is Plat'.

Recognition

Linthout's scripts for Luc Cromheecke's 'Roboboy' won the award for "Best Dutch-language author" and "Best Dutch-language Children's Author" at the 2003 Prix Saint-Michel Festival in Brussels. During the 2003 Stripdagen in Alphen aan den Rijn, the same series was awarded "Best Dutch-language children's album". His graphic novel series 'Years of the Elephant' won the Dutch Stripschapspenning for Best Literary Comic (2007), the Cultural Award of the Flemish Community (2008) and the Carolus Quintus Prijs for "Most Socially Relevant Comic" (2009). In 2009 ,he received the prestigious Flemish comics award the Bronzen Adhemar.

Legacy

On 8 April 2000, a statue depicting Urbanus, Amedee and Nabuko Donosor was erected in Tollembeek. The sculptures laugh at passers by, which is fitting since the statue stands on a square, not far from a school. On 7 July 2001, Urbanus also received a statue on the dyke of Middelkerke, as part of their local comic book route. In 2012, Linthout designed a biking route around his hometown in Eksaarde. He designed various road signs with Urbanus' image on it. Though bikers have to be careful, because the signs often deliberately point in the wrong direction. If one finds himself in the wrong spot, a cartoon of Urbanus can be seen, laughing at the gullible traveler. In 2017, 'Urbanus' was one of six comic series to be part of the Comics Station theme park near the Antwerp Central Station.

Comics shop Lambiek in the 'Urbanus' story 'De Laatste Hollander'.

Over the years, some Flemish cartoonists have given Linthout and his creations cameos. He, Urbanus, Jef Meert and the 'Urbanus' comic were spoofed in a vicious satire by former assistant Lukas Moerman, titled 'King Urbanus', published in the parody album 'Parodies. 20 Jaar Later' (Oranje, 1991). Urbanus had a cameo in 'Van Rossem' (1991), a celebrity comic by Erik Meynen about Jean-Pierre Van Rossem, also published by Loempia. Merho gave Linthout a cameo in 'De Kiekeboes' album 'Vluchtmisdrijf' (2009), where he appears as a comics collector. In the 'Jommeke' album 'Missie Middelkerke' (2017), written and drawn by Gerd Van Loock, Jommeke visits Middelkerke where one of the real-life comic book character statues depicted in the story is Urbanus. In 2019, it was announced that a comic mural will be created in Antwerp, paying homage to the 'Urbanus' comic series.

All these monuments, awards and comics cameos prove how much public opinion about Linthout's work has changed. Starting off in the most downgraded of all comics genres (celebrity comics, parody comics), he eventually became an awarded veteran artist, whose work has been exported, translated and was subject of a 2018-2019 retrospective exhibition in the Belgian Center of Comics in Brussels. With 'Urbanus', he created a hit series out of a celebrity comic, which kept running far beyond people's expectations. He made something children enjoy without feeling restricted. 'Urbanus' eventually outgrew its niche and became more than just a byproduct of a popular comedian. Some children have even discovered 'Urbanus' before they even heard about the real Urbanus. The comic strip contains enough satirical elements and wacky stories that adults can enjoy too. Without ever cleaning up his trademark style, 'Urbanus' has won the respect of all but the most prejudiced and elitist people (who will always be lampooned in the series, anyway). Linthout additionally showed his versatility by scripting more family friendly comics like 'Roboboy' and emotionally powerful graphic novels about serious topics, like 'Years of the Elephant' and 'Wat Wij Moeten Weten'. Again without changing much about his style. His long and versatile career is the triumph of someone who always did his own thing and proved the skeptics wrong.

Willy Linthout was an influence on Bavo.

Books about Willy Linthout

For those interested in the 'Urbanus' comics, the website www.urbanusfan.be is highly recommended, highlighting every possible aspect of the series. Tom Wouters published the equally insightful book 'Urbanus - Van Amedee tot Zulma' (Standaard Uitgeverij, 2019), which contains an interview with Linthout and Urbanus about both 'Urbanus' as well as their other comic series.

Typical back cover of the 'Urbanus' albums, featuring Willy Linthout as father Cesar and Urbanus as himself.