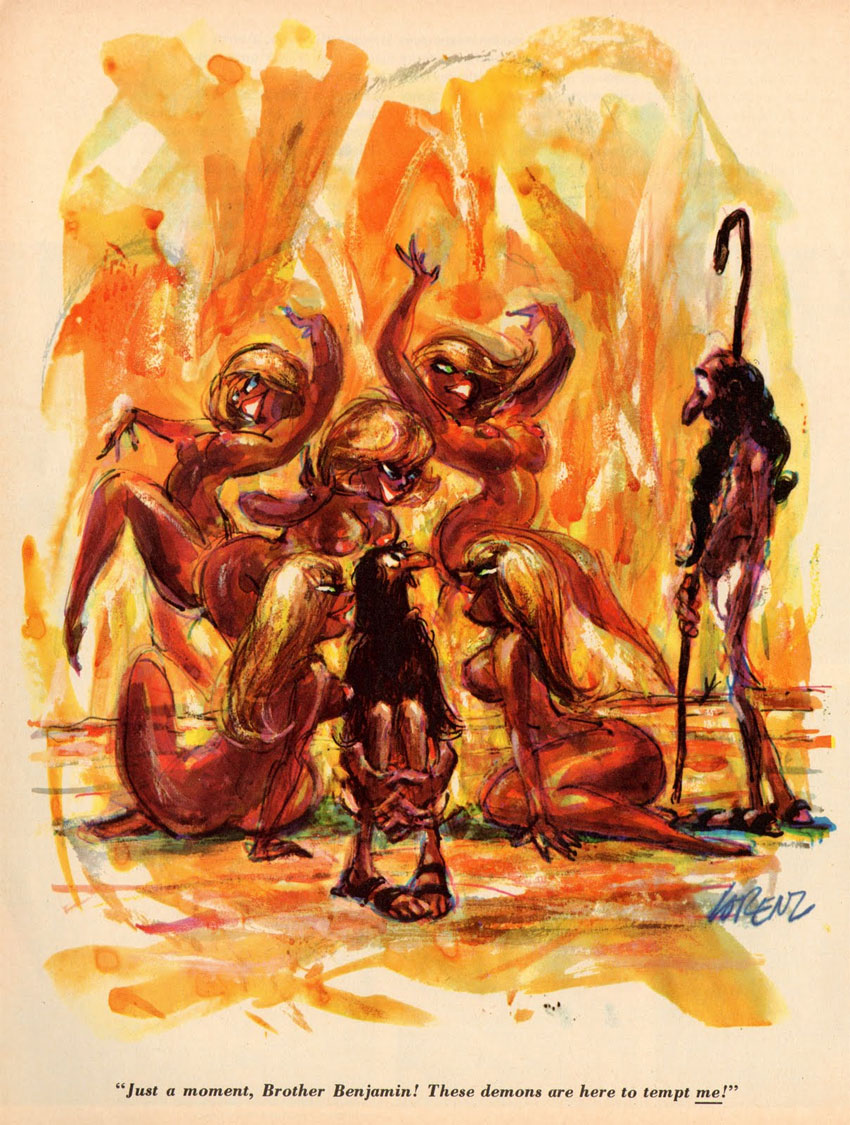

Lee Lorenz was an American jazz musician, cartoonist and book illustrator, best known for his cartoons in The New Yorker. Active from 1958 until 2015, he was one of the magazine's longest-running contributors. He also served as the magazine's art editor (1973-1993) and cartoon editor (1993-1997). Lorenz wrote, compiled and edited several thematic books for The New Yorker, including the very first historical overview 'The Art of The New Yorker 1925-1995' (Knopf, 1995). For Playboy and Pageant he drew cartoons in a more erotic style. He was additionally the first president of the short-lived Cartoonists' Guild.

Early life

Lee Sharp Lorenz was born in 1932 in Hackensack, New Jersey. His father organized USO shows for the YMCA, and his mother was a housewife. Lorenz' family moved several times, first to Leavenworth, Kansas, then when he was nine or ten to White Plains, New York, later Newburgh, New York, before eventually settling in 1947 in Greenwich, Connecticut. He inherited his creative side from his mother, who always wanted to become a writer or poet, but never got further than being a greeting card designer. At Greenwich High School, Lorenz wrote and drew a satirical history of his class for the senior yearbook. One of his classmates was the son of cartoonist Jack Morley, who encouraged Lorenz to become a professional artist. Between 1950 and 1951, Lorenz studied art at Carnegie Institute of Technology (nowadays Carnegie Mellon University) in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Since Pittsburgh was a difficult place to make a living, he moved to New York City. In 1954, he obtained a Fine Arts degree from the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, where one of his teachers was the famous painter Philip Guston. Guston was also best man at Lorenz' wedding.

Among Lorenz' main graphic influences were Milton Caniff, Gene Deitch, William Steig and Saul Steinberg. But as a young adult he was far more interested in jazz. He performed as a cornet player in a Dixieland Jazz band, Eli's Chosen Six. The group toured many college campuses and even performed at the Newport Jazz Festival, a moment captured in Bert Stern and Aram Avakian's classic concert film 'Jazz On A Summer's Day' (1958). Lorenz remained active as a jazz musician for the rest of his life. He performed in two other bands, The Creole Cookin' Jazz Band and The Gotham Jazzmen, which all gave him a steady income.

Cartooning career

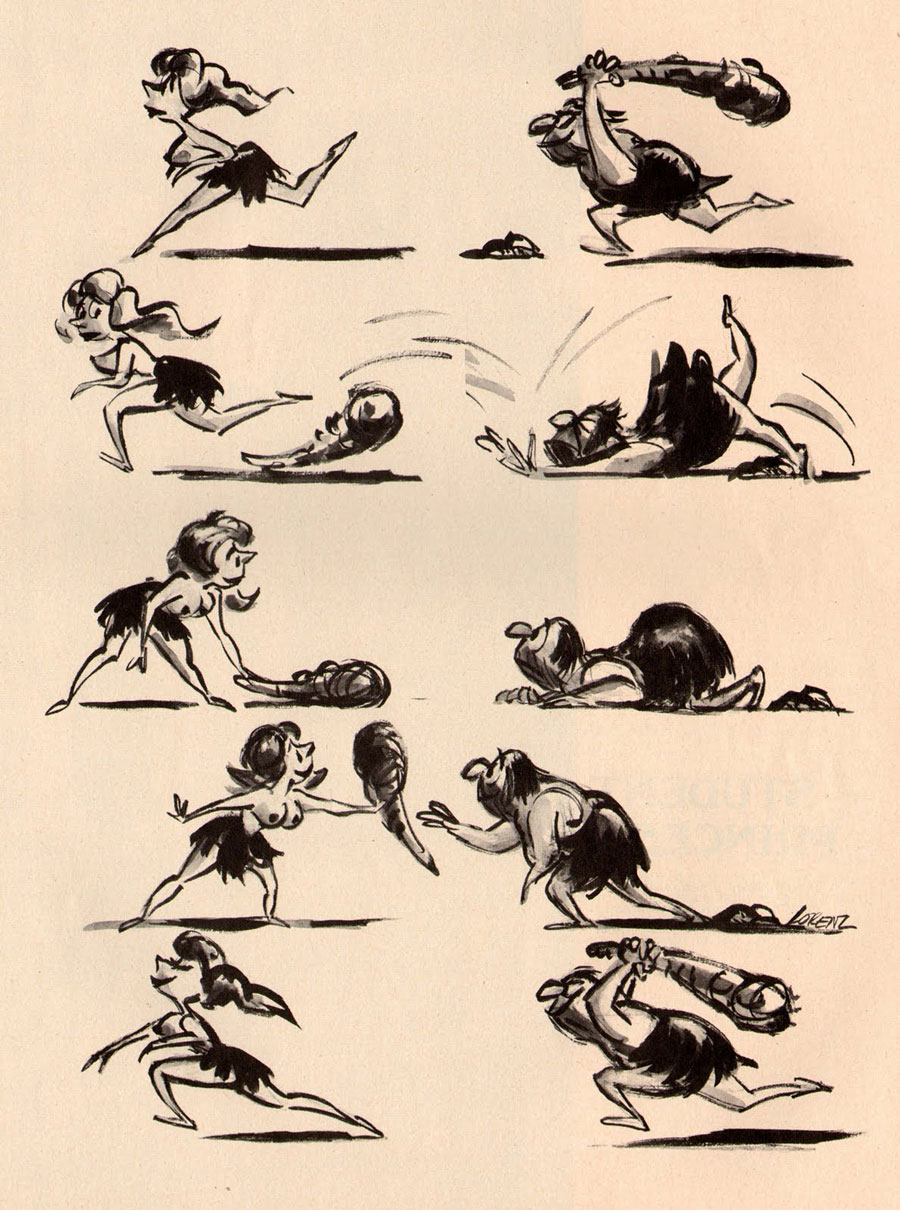

Lorenz' graphic career took off in the mid-1950s when he sold gag ideas to cartoonists. He also started drawing ones himself. In 1956, he sold his first cartoon to Collier's magazine. Within two years he was hired by The New Yorker. Over the decades he published in many other magazines, including 1000 Jokes, Argosy, Look, Pageant, Post, Sports Illustrated, True and Hugh Hefner's Playboy.

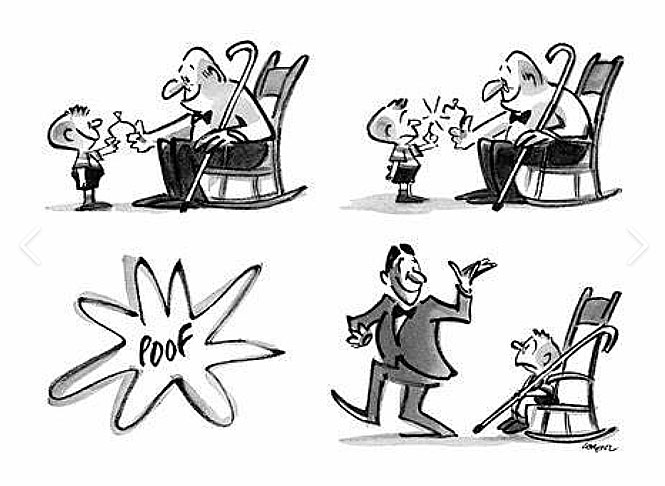

Comic strip by Lee Lorenz.

The New Yorker

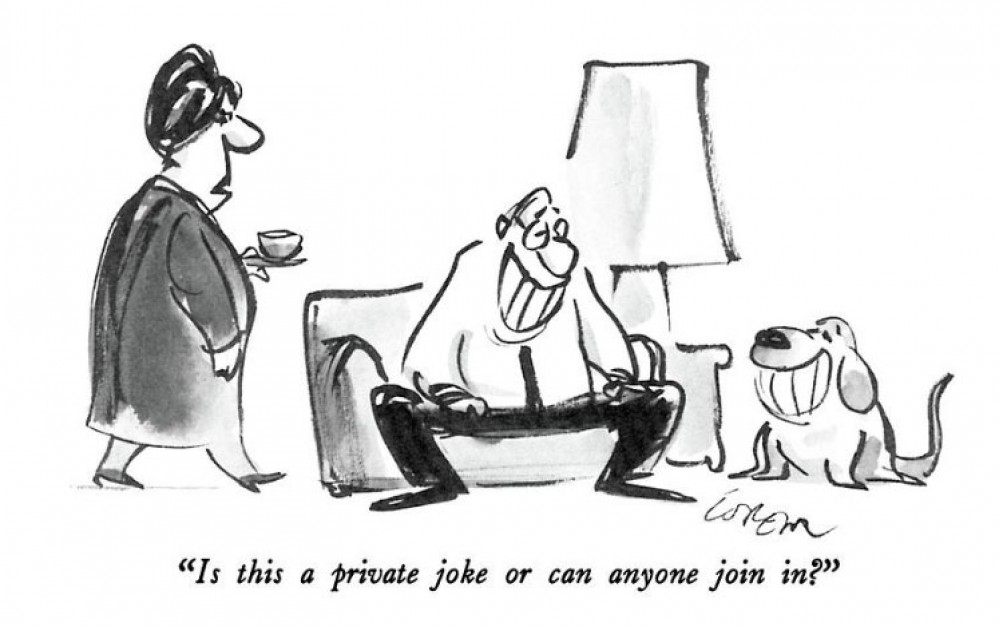

In 1958, Lorenz first published in the magazine he is mostly associated with, The New Yorker. He was lucky to be instantly hired as a contract cartoonist. Originally he mostly thought up gags for their established graphic contributors, like Charles Addams, George Price and Richard Taylor. His earliest cartoon of his own appeared in print on 8 March 1958. Over the course of more than half a century, Lorenz contributed many more. In a 2011 interview with The Comics Journal, Lorenz mentioned he experienced a creative breakdown in the early 1960s. Although he had plenty of ideas for cartoons in other magazines, he no longer couldn't come up with anything he felt suited The New Yorker. Through psychological help and the support of his New Yorker editors Jim Geraghty and William Shawn, he got rid of this irrational fear.

As a cartoonist, Lorenz was most notable for his airy brush technique. At the time, many cartoonists in The New Yorker used a very detailed drawing style, while he had a simpler approach. Critic/journalist Richard Gehr compared him to a jazz musician, creating a "free-flying spirit of a music that sounds dated while still epitomizing the improvisational whimsy informing so much modern art." Lorenz' cartoons found endless thematic inspiration in the absurdities of life. He had a particular knack for old people. Many of his cartoons star nagging senior citizens who annoy their partners, pets, doctors, psychiatrists and other unfortunate bystanders. Though Lorenz also admitted that, "after so many years of drawing old farts, I had become one (...) and (...) was right all along."

Lorenz' final cartoon in The New Yorker appeared on 12 January 2015. At that time, with 57 years on his track record, he was one of their longest-running cartoonists. Compilations of his work have been published under the titles 'Here It Comes: A Cartoon Collection' (Indianapolis, Bobbs-Merrill, 1968), 'Now Look What You've Done' (Pantheon, New York, 1977), 'The Golden Age of Trash: Cartoons for the Eighties' (Chronicle Books, San Francisco, 1987) and 'Old Farts Are Forever' (Andrew McMeel Publishing, 2009).

Sequential cartoon for Cavalier (May 1967).

Editorship

In 1973, Lee Lorenz succeeded James Geraghty as The New Yorker's art editor. Although his predecessor had decades-long experience, he wasn't a cartoonist himself. In this field, Lorenz had an advantage, since his trained eye instantly noticed whether a cartoon was good or not. Yet he only gave his colleagues notes if he thought the look or a caption could be improved in function of the punchline. Otherwise Lorenz had more of a "hands off" approach. In interviews he stated that his power as a talent scout was the "most important part of his job."

During his run he discovered many new talents and brought well-established cartoonists from other magazines in The New Yorker's pages. Among them were Barry Blitt, Roz Chast, Frank Cotham, Michael Crawford, Leo Cullum, Liza Donnelly, Jules Feiffer, Sam Gross, Bruce Eric Kaplan, Nurit Karlin, Arnie Levin, Bob Mankoff, Michael Meslin, Lou Myers, John O'Brien, Victoria Roberts, Sempé, Barbara Smaller, Edward Sorel, Peter Steiner, Mick Stevens, P.C. Vey, Bill Woodman and Jack Ziegler. Two of them, Michael Maslin and Liza Donnelly, actually married after having met each other at The New Yorker's editorial board. Lorenz favored cartoonists with a "distinctive point of view." He also preferred people who didn't have to rely on gag writers, but thought up their own punchlines. In 1993, he resigned as art editor and was succeeded by Françoise Mouly. He then continued as the New Yorker's cartoon editor, a position he held until 1998, when Robert Mankoff succeeded him.

Books about The New Yorker

In addition, Lee Lorenz published several books about The New Yorker. Among them is 'The Art of The New Yorker 1925-1995' (Knopf, 1995), the first comprehensive and chronological compilation of the magazine's long history. He did a lot of research, gaining access to a large collection of memos between founder Harold Ross and his employed cartoonists. It led to a thorough chronicle and analysis of The New Yorker's history and signature style, also printed in the book. Together with Jules Feiffer, Lorenz provided the foreword to Liza Donnelly's 'Funny Ladies: The New Yorkers Greatest Women Cartoonists and their Cartoons' (2005). He additionally provided the preface to Robert Mankoff's 'The New Yorker Book of Teacher Cartoons' (2012), a compilation of school-themed cartoons.

Lorenz also compiled and edited various books about individual New Yorker cartoonists, like George Booth ('The Essential George Booth', Workman, 1998), Charles Barsotti ('The Essential Charles Barsotti', Workman, 1998), William Steig ('The World of William Steig', Artisan, 1998) and Jack Ziegler ('The Essential Jack Ziegler', Workman, 1998). Whenever a New Yorker cartoonist passed away, he also usually wrote a personal obituary in the next issue.

Book illustrations

Lorenz was a prolific book illustrator. He livened up the pages of children's books like Richard J. Margolis' 'The Upside-Down King' (Windmill Books, 1971), Jan Wahl's 'Sylvester Bear Overslept' (Parents Magazine Press, 1979), Bonnie Pryor's 'Mr. Munday and the Space Creatures' (Simon & Schuster, 1989), Charles Keller's 'Driving Me Crazy: Fun-On-Wheels Jokes' (Pippin Press, 1989), 'Remember the A La Mode: Riddles and Puns' (Prentice Books, 1986), 'Waiter, There's a Fly In My Soup! Restaurant Jokes' (Simon & Schuster, 1986), David Updike's 'Seven Times Eight' (Pippin Press, 1990) and Jill Lorenz Caruso's 'Ava Queen of the Jungle' (Blue Velvet Books, 2016).

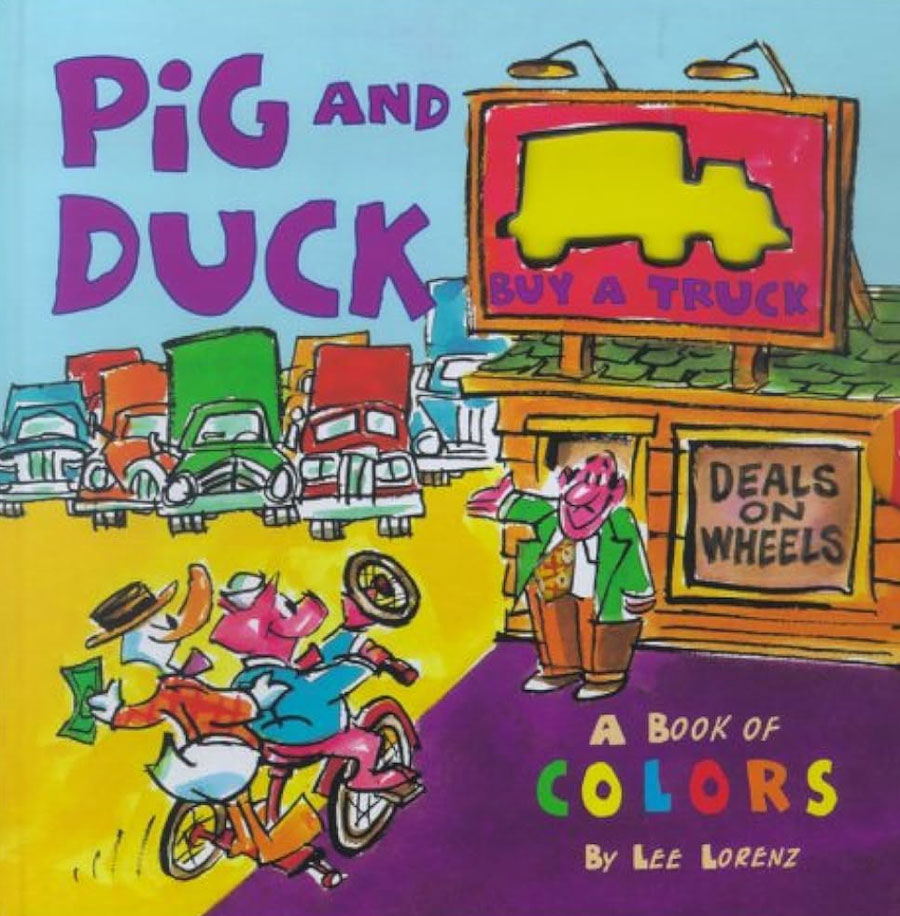

Lorenz additionally wrote and illustrated several books of his own. Two were based on Geoffrey Chaucer's classic narrative poem 'The Canterbury Tales', namely 'Scornful Simkin: Adapted from Chaucer's The Reeve's Tale' (Prentice Hall, 1980) and 'Pinchpenny John: Suggested by Incidents in Chaucer's The Miller's Tale' (Prentice Hall, 1981). Among his original children's books were the titles 'Big Gus and Little Gus' (Prentice Hall, 1982), 'The Feathered Ogre' (Prentice Hall, 1983), 'Hugo and the Space Dog' (Prentice Hall, 1983), 'A Weekend in the Country' (Prentice Hall, 1985), 'Dinah's Egg' (Simon and Schuster for Young Readers, 1990), 'A Weekend in the City' (Pippin Press, 1991) and 'Pig and Duck Buy A Truck: A Book of Colors' (Little Simon, August 2000). 'The Feathered Ogre' has also been translated in French as 'L'Ogre à Plumes'.

Lorenz was especially in demand as an illustrator of humor books. He livened up Jeanne K. Hanson & Patricia Marx 'You Know You're Grown Up When...' (Workman Publishing Company, 1991) and 'You Know You're A Workaholic When...' (Workman Publishing Company, 1993). Laughable excerpts from real-life court cases form the backbone of Rodney R. Jones', Charles M. Sevilla and Gerald F. Uelmen's 'Disorderly Conduct' (W.W. Norton & Company, 1987), 'Supreme Folly' (W.W. Norton & Company, 1993), and 'Law and Disorder' (W.W. Norton & Company, 2014). Lorenz delved into the world of palindromes with Allan Miller's 'Mad Amadeus Sued A Madam' (David R. Godin, 1997). His most popular illustrated humor books were Bruce Ferstein's 'Real Men Don't Eat Quiche: A Guidebook To All That Is Truly Masculine' (1982) and 'Real Men Don't Bond: How To Be A Real Man in an Age of Whiners' (1992) and Joyce Jillson's 'Real Women Don't Pump Gas: A Guide to All That Is Divinely Feminine' (Pocket Books, 1982). It inspired Lorenz to make a spoof of these books, 'Real Dogs Don't Eat Leftovers: A Guide to All That Is Truly Canine' (Holiday House, 1983), written and illustrated by himself.

Cartoon for Cavalier (March 1966).

Recognition

In 1995, Lee Lorenz received the Gag Cartoon Award from the National Cartoonists Society.

Other activities

Lorenz was also part of the board for the Museum of African Art. He was a trustee for the non-profit organization Swann Foundation for Caricature and Cartoon, which promotes cartooning. Lorenz was additionally the first president of the Cartoonists Guild, who guarded the (financial) interests of professional cartoonists. The Cartoonists Guild tried to raise rates for cartoonists, standardized the return of original artwork to the respective creators and passed along magazine requests for reprints. However, the Cartoonists Guild was discontinued when it became too much of a business.

Death

Lee Lorenz died in 2022, at age 90, in his home in Norwalk, Connecticut.