"Away with the old establishment!"

Fritz Behrendt was a German-Dutch political cartoonist, active between 1953 and 2008. He was house cartoonist of the newspapers Algemeen Handelsblad (1953-1968), Het Parool (1968-1988) and De Telegraaf (1988-2008). Before his long career started, Behrendt was active in the Resistance during World War II and imprisoned by the Nazis. After the war, he joined the Communist International Youth Brigade in Yugoslavia and East Germany, until he was jailed by them too. Having been detained by two opposing extremist ideologies, Behrendt would devote the rest of his life to drawing political cartoons, becoming one the few Dutch editorial cartoonists to enjoy international fame. His graphic views on global politics ran in papers all over the world, and often led to angry reader's letters and even offended reactions from some of the portrayed politicians themselves. Yet Behrendt was also praised for his virtuoso graphic style and sharp commentary. He received several awards and compliments, including from U.S. President John F. Kennedy.

Early life

Fritz Alfred Behrendt was born in 1925 in Berlin, Germany. His father was a baker. At age 11, the boy attended the opening ceremony of the Olympic Games in Berlin on 2 August 1936, where he saw Adolf Hitler during the parade. Back home, he made a caricature of him, which he considered his first "political cartoon". Since his parents were Jewish, they felt increasingly unwelcome in their home country. In 1936, the Gestapo wanted to arrest his father, but escaped by jumping in a train to The Netherlands. There, he settled in Amsterdam, securing a new home for his family. By 1937, the rest of the Behrendt family received permission to move from Berlin to Amsterdam. All the while, a local German police officer had strongly motivated Behrendt's mother to divorce from her Jewish husband.

As a twelve-year old boy, Behrendt felt estranged in his new homeland. In 1938, his earliest published drawing appeared in the youth supplement of the Dutch paper Het Volk. Editor Annie Winkler-Vonk then showed his drawings to the cartoonist Jo Spier, who felt that Behrendt would benefit from taking a graphic course at publishing company De Arbeiderspers. Unfortunately, on the very day of his planned visit - 10 May 1940 - Hitler invaded The Netherlands. At his parents' advice, Behrendt decided to follow in his father's footsteps and become a baker. In 1941, his father was arrested by the SS. During his absence, Behrendt became the breadwinner of the family, working in a pharmaceutical factory. A year later, his father was freed, but Behrendt now faced another problem. He was old enough to either work in German factories, or be drafted into the army. Using the Nazi racial policies against the oppressor, Behrendt pointed out that he wasn't "Aryan" enough to be recruited. They agreed and he was registered into the reserve army of the Luftwaffen-Feld-division. Between 1943 and 1944, Behrendt studied at the Amsterdam Arts and Crafts College (the Kunstnijverheidsschool, nowadays the Gerrit Rietveld Academy). It offered a perfect excuse to avoid being drafted, while simultaneously being on the career path he had aspired to in the first place. Indeed, the very reserve army he could have been serving in, was soon sent to Russia, where the Nazis fought an ill-conceived invasion with barely anyone coming back alive.

Although he was safe for now, acquiring a few additional graphic skills, Behrendt learned more from talking with his teachers and fellow students than the lessons themselves. Frequent bombings interrupted school hours. One day, Behrendt and his classmates witnessed Nazi planes gunning down three British aircrafts. Although the English aviators were able to parachute down, they were still shot dead before reaching the ground. As he witnessed these horrid events, Behrendt told his teacher and classmates that they "could no longer keep drawing flowers, but had to do something." He joined an anti-fascist student organization and secretly worked for the Dutch resistance. In the fall of 1944, the southern half of the Netherlands was liberated by the Allied Forces, while the northern half, including Amsterdam, remained occupied by the Nazis. A long and dreadful period followed, known as the "Hunger Winter", during which citizens in the North had to combat famine and an ice cold winter. The Academy closed down, interrupting Behrendt's graphic education once again. In the spring of 1945, only a few weeks before the end of the war, Fritz Behrendt was arrested and jailed in the Weteringschans prison. Like all political prisoners, the Nazis planned to execute him. Soon after, however, the Allied Forces liberated Amsterdam and Behrendt got off scot-free.

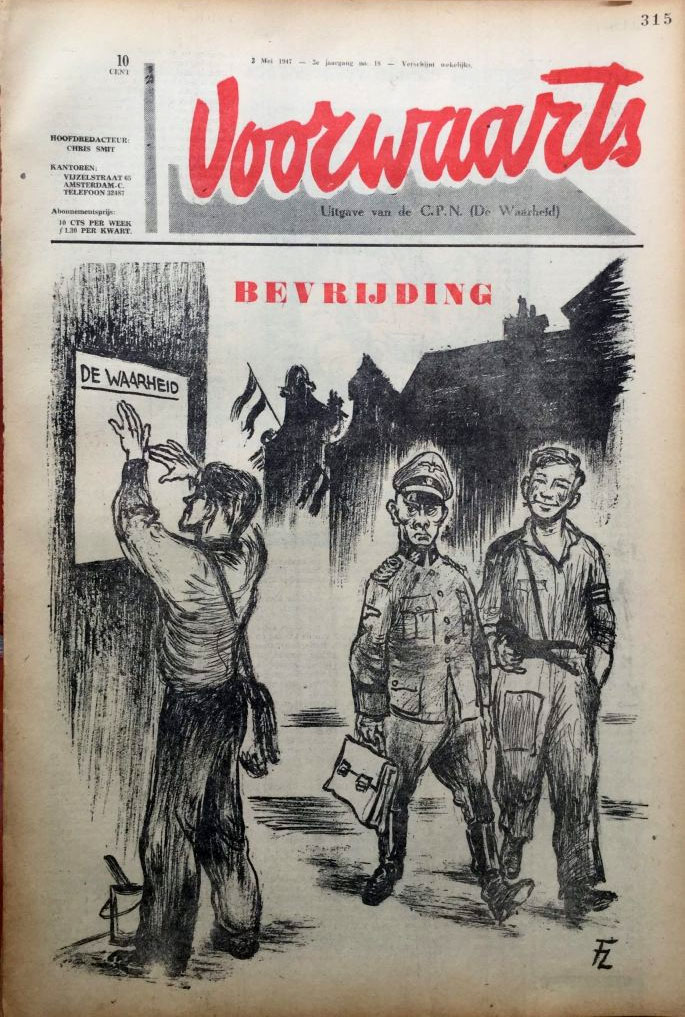

Cover cartoon for Voorwaarts (May 1947).

Post-war communist activism and disillusions

Although World War II was over, Behrendt didn't abandon his socially conscious activities. Having suffered under five years of Nazi occupation, he became a fiery Communist. Directly after the war, Soviet Russia was still respected for bringing Nazi Germany to its knees, in alliance with The United States and The United Kingdom. The same applied to Yugoslavia, where the partisan army led by field marshal Josip Broz Tito had bravely fought back against the Nazi oppressors. Behrendt published his first political cartoons in the Dutch Communist weekly Voorwaarts, where some of his colleagues were the illustrators Alex Jagtenberg and Max Velthuijs. Among his own graphic influences were David Low and Boris Yefimov.

In 1947, Behrendt traveled to Yugoslavia as commander in the Algemeen Nederlands Jeugd Verbond, a Communist youth league led by Gerrit Jan van der Veen. He later joined the International Youth Brigade too. They helped rebuild the war-torn country by working on the railway between Samac and Sarajevo. A year later, Behrendt was project leader and interpreter during the construction of the motorway between Zagreb and Belgrade. As a reward for his efforts, he was given money to pay for his studies. Between 1948 and 1949, Behrendt honed his graphic skills at the art academy of Zagreb. He made political cartoons for Kerempuh, a Communist magazine circulating in this city. In this magazine, Croatian cartoonist Oto Reisinger also published drawings. He and Behrendt became lifelong friends. Behrendt would even be responsible for launching Reisinger's career in the West.

In 1949, Germany was divided. The Western part (BRD) remained an independent democracy and ally of the capitalist states. The Eastern part (DDR) became a Communist puppet state, dictated by the Soviet Union. At the time, future head of state Erich Honecker was still leader of the Communist youth movement Freie Deutsche Jugend. At his request, Behrendt traveled to East Berlin in May 1949, where his graphic skills were used for propaganda purposes. The young cadet published cartoons for the youth magazine Junge Welt and made illustrations for a local publisher. He also made a design for the coat of arms of the DDR. For his efforts, he was bestowed with honorary medals and recommendations. Still, only parts of his official design were later included in the official coat of arms of the DDR.

All of Behrendt's optimism about Communism was shattered when on 9 December 1949 Honecker ordered his arrest. Around that time, Yugoslavian head of state Josip Broz Tito took a more independent course, instead of blindly obeying the Soviet Union, and fell out of grace with Joseph Stalin. Soon anybody with Titoist sympathies, or who had once worked for Yugoslav Communist organizations, like Behrendt, was suddenly suspicious. For six months, he was kept in solitary confinement in an East Berlin prison, even though his only "crime" was asking critical questions. His cell was small, with barely any facilities. He was only brought out for interrogations by the secret police, the Stasi. To avoid going insane, Behrendt started walking around in his cell, pretending he was traveling. He imagined himself driving a car, taking a train and visiting places. The worst part was that none of his friends or relatives in The Netherlands knew that he had been imprisoned, let alone where, as he wasn't allowed to write or phone anybody. Eventually, he was able to talk to another prisoner, who was about to be released. He promised to send Behrendt's family a secret message regarding his whereabouts. After having reached them in Amsterdam, they immediately contacted the Dutch embassy in East Berlin, who were able to get Behrendt free again. On 9 June 1950, Fritz Behrendt left East Berlin, where his father would pick him up to return to Amsterdam. But Behrendt refused to go before he had one final conversation with Honecker. His father declared him insane, but Behrendt still went to Honecker and confronted him with what happened. Honecker was very intimidated, but defended himself that "in times of revolutionary alert, it's better to jail 99 innocent people instead of letting one guilty person go free." Behrendt told him that this was the mentality of their opponents, which they fought against, and that they would never be able to build a society by crushing anybody who wanted something different.

Cartoon signed with "Igel" for Der Tarantel issue #53 (1955). Translation from German: "So, gentlemen, now you sign the protest against the Treaty of Paris."

His jail experience changed Behrendt. Now he was one of the few political cartoonists to have enjoyed the "honor" of being imprisoned by two different, diagonal totalitarian ideologies. For the rest of his career, he devoted his graphic talent to combat international injustice, whether Fascist, Communist or any other kind. He became particularly opposed to Communism, of whom he had now seen the true face. For all their promises of egalitarianism and political-economic-social-scientific progress, these regimes were just another totalitarian dictatorship, oppressing common people. After his release, under the pen name Igel, Behrendt contributed satirical drawings to Der Tarantel, a CIA-funded magazine produced in West-Berlin and distributed illegally in the DDR, mocking the establishment of the Soviet Union, the East-German Communist Party and its government officials.

"25 years after the Liberation: You never know who stands next to you in a German streetcar..." (1970).

Career in the Dutch and international press

In the early 1950s, Behrendt's political cartoons ran in the Dutch weekly opinion magazine Vrij Nederland and the official socialist party magazine Arbeid. On 6 March 1953, the Amsterdam newspaper Het Parool published one of his cartoons on its front page. The illustration referenced Joseph Stalin's recent passing: it showed the old dictator sharing a table with all the Soviet politicians he had betrayed, deposed or executed, hanging his head in shame. The stinging line underneath read: "The old Politburo has reunited." But since Leendert Jordaan was already the house cartoonist of Het Parool, Behrendt instead joined Algemeen Handelsblad. After creative differences with the paper's new chief editor Henk Hofland, in March 1968, Behrendt left Algemeen Handelsblad and joined Het Parool, where his cartoons ran for the next twenty years. In 1988, he was fired for a controversial cartoon about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, whereupon he went to rival paper De Telegraaf, which ran his political drawings until the cartoonist's death in 2008.

Behrendt also sold his cartoons to foreign publications, making him the most widely read Dutch political cartoonist of his time. In West Germany, he appeared in Hamburger Abendblatt, Die Welt, Der Spiegel, Der Tagesspiegel and, from 1972 on, in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. In Switzerland, Behrendt's work ran in Der Nebelspalter and Die Weltwoche, while in Austria readers knew him from his contributions to the Neue Kronen Zeitung. He additionally published in Belgium (De Nieuwe Gazet), Norway (Afteposten), Denmark (Berlingske Tidende), Sweden (Svenska Dagbladet), the United Kingdom (Punch), Greece (Kathimerini), Israel (Ma'ariv), Japan (Shimbun), Australia (The West Australian) and the United States (The Los Angeles Times, The New York Herald Tribune [1958-1964], The New York Times and Time). Despite his reputation as an anti-Communist cartoonist, the Soviet press also published some of his cartoons, though only if they criticized Capitalism, the NATO or U.S. imperialism.

Cartoon about German rearmament, printed in the German magazine Die Welt (27 September 1954). Translation: "How France wants the German army to be: stronger than the Soviet one, weaker than the French one." The man in German uniform is West German chancellor Konrad Adenauer, while the man in French uniform (right) is French President René Coty.

Book collections

Fritz Behrendt's cartoons were collected in the books 'Geen Grapjes, A.U.B.' (Algemeen Handelsblad, 1957), 'Kijken Verboden. Een Kijkje Achter Het Gordijn in 70 Caricaturen' (Nijgh & Van Ditmar, 1957, reprinted in 1961), 'Ondanks Alles' (Nijgh & Van Ditmar, 1962), 'F. Behrendt's Omnibus' (Nijgh & Van Ditmar, 1965), 'De Volgende, A.U.B.' (also translated into German as 'Der Nächtste Bitte', 1971), 'Helden en Andere Mensen' (translated into English as 'Heroes and Other People' and German as 'Helden und andere Leute', Econ, 1975), 'Hebt U Marx Nog Gezien?' (Nijgh & Van Ditmar, 1977), 'Op Naar Het Jaar 2000' (Keesing, 1982), 'In Vredesnaam' (Elsevier, 1984), 'Waakzaam en Steeds Paraat. NAVO en Warschau Pact in Karikatuur' (De Bataafsche Leeuw B.V., 1994), 'Grafische Signalen' (Van Soeren & Co., 2000) and 'F. Behrendt - Een Europees Tekenaar' (Van Soeren & Co, 2005).

Cover for the English edition of 'Grandfather was defenceless...' (1983).

The 1978 book 'Israël: Tussen Sjalom en Jihad' (Nijgh & Van Ditmar, in 2003 reprinted by Soeren en Van Co.) was published in collaboration with the foundation Christenen voor Israel ("Christians for Israel"). Behrendt's book 'Grootvader was Weerloos' was also translated into English as 'Grandfather was Defenceless...' (Ma 'ariv Book Guild, 1983). 'Het Was Stil Vandaag in Sarajevo' (Van Soeren & Co, 1994) collects drawings regarding the war in former Yugoslavia (1991-1995) and received a more optimistic sequel, 'Er Is Weer Hoop in Sarajevo' (Van Soeren & Co., 1998). Jaap de Hoof Scheffer, secretary-general of NATO (2004-2009) provided the foreword to Behrendt's book 'Tussen Grebbeberg en Uruzgan. De Nederlandse Krijgsmacht in de Periode 1940 tot Heden' (Van Soeren & Co., 2008), an overview of the Dutch army during World War II and afterwards.

"How the times have changed" (1960). The four begging white politicians are West German chancellor Konrad Adenauer, East German chancellor Walter Ulbricht, U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower and Russian head of state Nikita Khrushchev.

Style

Behrendt worked in a very detailed, elaborate style. Whether caricatures of famous politicians, certain people in society or simple bystanders: each individual is portrayed very specifically. Beyond the main message, readers can marvel at the witty personalizations and extra amusing background gags. A prime example is the cartoon Behrendt made after the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy in 1968, which portrays various Americans from all layers of society posing with guns, from a hillbilly, Ku Klux Klan member and mafiosi, to a senior citizen, a housewife, children and even two babies. Another detailed cartoon is Behrendt's 1967 "celebration" of the Soviet Union's 50th anniversary. The drawing depicts international Communism as a carnival show, titled 'The Marx Brothers Ltd.', and promises "show, shock and sensation". Several former and (then) current heads of state are portrayed as circus entertainers. Karl Marx is the cashier, Lenin bangs the drum, Ho Chi Minh throws knives at a Southern Vietnamese man, Fidel Castro is a fire eater, Joseph Stalin uses DDR leader Walter Ulbricht as a ventriloquist dummy and Russian head of state Leonid Breznhev and Minister of Foreign Affairs Alexej Kosygin are Siamese twins. But while a bystander stares in disbelief at the spectacle, his son pulls his arm to move on.

People marvel at the Communist ideas of Karl Marx, but are shocked that, in practice, the system actually leads to totalitarian terror, represented by Joseph Stalin.

Behrendt could also strike readers with one, simple, powerful image. Another cartoon commemorating the 1967 bicentennial of the Soviet Union has the byline: "A lot has been achieved". It shows a city with huge factories, buildings and statues, while rockets, satellites and bombs fill the sky. Yet in the center of the drawing is a little bare tree, with a deeply depressed man underneath, covering his head in his arms. Another moving drawing by Behrendt shows the corpse of one soldier, with the haunting cold commentary: "Our losses were rarely so few." Some of his cartoons were made in charcoal, reducing people to more stylized lines and stripes. This didn't diminish their impact, however. In 1956, the Hungarian Uprising against the Soviet Union was brutally crushed, with 117,000 people fleeing the country. Behrendt read that a Hungarian radio propaganda channel had covered the event with the blatant lie: "A group of fascist spies and agents have left our country." He instantly made a charcoal drawing of a long line of people crossing a snow landscape, with a mother up front, carrying a baby and holding a daughter by hand. Another silence-inducing cartoon by Behrendt was made after the execution of Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann in 1962. The subtitle references one of his testimonies during the trial: "I only did my duty", with Behrendt portraying Eichmann's detached face among millions of his victims.

On occasion, Behrendt made cartoons with apolitical themes too, like the holiday season, the sexual revolution and TV addiction.

Cartoon depicting Syrian president Hafez Al-Assad and Egyptian president Anwar Al-Sadat threatening Israel, but acting hurt even before Israel has actually taken violent action.

Controversy

Since Behrendt's cartoons were internationally syndicated, it increased the number of his admirers, but also of his critics. Some critics claimed that he pandered too much to conventional positions average Western citizens would easily agree with, explaining why he was so easily universally accepted. His cartoons often criticized Communism and Muslim fundamentalism far more sharply than the USA or Israel. Contrary to other political cartoonists from his generation, he portrayed certain controversial politicians, like Lyndon B. Johnson, Richard Nixon, Golda Meir, Henry Kissinger, Ronald Reagan and Menachem Begin, with far more dignity and respect. Behrendt was also one of the few to not portray Mikhail Gorbachev with his iconic wine mark on his forehead. While his colleagues couldn't resist poking fun at this birth defect, he felt this was in bad taste. Younger generations therefore sometimes dismissed Behrendt as a square conservative. Journalist Jan Blokker used to mockingly greet him with the line "Hi, fascist!", whenever they met at the office.

Behrendt's anti-Communist stance made him particularly unpopular with youngsters during the 1960s and 1970s, who sympathized with Marxism and Maoism and were critical of Western involvement in the Vietnam War. His reputation was such that his cartoons were banned in all Communist countries. Only the Soviet press occasionally printed some of them, if they criticized the West. One time the Finnish paper Hufvudstadsbladet informed Behrendt that they wouldn't publish political cartoons about Soviet leaders for a while, since a Russian delegation planned a state visit to Helsinki.

To Behrendt, his criticism of Communism was a personal matter. After having done so much humanitarian work in Yugoslavia under the red banner, his 1949-1950 jail time in East Germany felt like a betrayal. He observed that whenever a country became Communist, it unavoidably became a dictatorship. Even countries who had been Communist for several decades now, like Russia, China and Cuba, never became a true democracy, despite all their promises. Interviewed by Arnold Vasen for the 28 December issue of the magazine Studio, Behrendt dismissed criticism that he was a Communism hater: "I'm very combative against any dictatorship, both from the left as the right. I don't like fanatics. But this doesn't mean I'm spiteful in my drawings, like Honoré Daumier and Albert Hahn, Sr., They were driven by a fiery fire, they must have gotten terribly angry. I can't do that." Still, he was delighted to live long enough to see the Cold War thaw, the Iron Curtain and Berlin Wall crumble and the Soviet Union dissolve.

Cartoon that got Behrendt fired from Het Parool in 1988, depicting PLO leader Yasser Arafat and Israeli Prime Minister Shimon Peres. Translation: "The Israelis shouldn't be so militant, but should seek an unarmed dialogue and particularly talk with the PLO. Strange, how the Jews used to be far more tolerant in the past."

His pro-Israel stance was also explained by previous jail time, being imprisoned during World War II for his Jewish roots and resistance against the Nazi occupation. Behrendt therefore opposed antisemitism and supported the Israeli state. A 1988 comic strip regarding the Israeli-Palestinian conflict was even directly responsible for his discharge from the newspaper Het Parool. At the time, the Israeli army came to blows with the Palestinian population, who, by lack of weapons, fought back by throwing stones at soldiers, an event that went down in history as the "First Intifada". In Behrendt's comic, he ironically expressed the viewpoint that the Israelis "should seek unarmed dialogue with the P.L.O.", while his drawings show how impossible this is, given the P.L.O.'s hostility. In the final panel, Nazis deport Jews, with the line: "How odd, back in the day, Jews were far more tolerant." For Het Parool's chief editor Sietze van der Zee, this cartoon was the final straw. They never got along anyway, but he also had other reasons to fire Behrendt: Van der Zee's father had been a Nazi collaborator during World War II. While he was a boy back then, he was severely traumatized by the vengeful reactions against his parents after the war. From this perspective, he certainly didn't want to associate his paper with images of Nazi deportation.

Still, Behrendt also acknowledged that divisions between Israeli and Arab fanatics were the real root for much of the bloodshed in the Middle East. One of his cartoons depicted the graves of a Palestinian and an Israeli, with the subtitle: "Finally peacefully next to each other." Another iconic drawing portrays an Israeli soldier and Palestinian militant staring at each other with suspicion, while their children happily play with each other. The subtitle reads: "Hope…" On the same token, Behrendt made several cartoons criticizing the U.S. government, capitalism, the Western war industry, racism and even intolerant conservatives who erroneously claim that "things used to be better in the past." Behrendt always sympathized with the average citizen, victimized by oppression, torture and execution, regardless what country they lived in. As he explained in his own words: "I'm a fierce opponent of patented recipes to change the world with violence. The cynicism of Soviet leaders is just as horrid to me as the icecold materialism of industrial mandarins, whose anti-communism has a suspicious smell."

Any criticism of Behrendt's supposed "one-sidedness" is easily countered by the sheer amount of people from both sides of the political spectrum who were offended by his work. In many papers, readers wrote complaints or requested cancellation of their subscription. In 1961, the terrorist organization O.A.S. attempted to depose French president Charles De Gaulle, since he planned to grant the former French colony Algeria independence. Behrendt portrayed O.A.S. leader Raoul Salan as a pirate and doubled the final "S" of the word "O.A.S", to reference the Nazi organization S.S. The O.A.S. sent an official letter of threat. In February 1963, Behrendt criticized Indonesian president Achmed Sukarno with his belly full with New Guinea, licking his lips at the prospect of devouring North Borneo. When the cartoon ran in the Berlin paper Der Tagesspiegel, it caused a major demonstration in front of the German embassy in Malaysia.

In October 1963, Behrendt drew a cartoon, depicting John F. Kennedy and Nikita Khruschev dining on the Berlin Wall, while Charles De Gaulle and Mao, both portrayed as irritating dogs, gnaw at their coats. De Gaulle happened to see the drawing when it ran in the magazine NATO's Fifteen Nations and wrote a personal complaint. The editor was so frightened of losing French advertisers that he asked Behrendt to "temper down" and not send any cartoons for a while. This "while" eventually became a pure cancellation. In September 1964, the German magazine Der Spiegel reprinted a drawing showing politicians Hans-Christoph Seebohm, Walter Ulbricht and Franz Jozef Strauss with the tagline "Hand in hand, against reason and mind." Seebohm and Strauss were notorious for their extreme right-wing conservative opinions, while Ulbricht was the leader of the East-German Communist Party and thus de facto the head of state. Strauss felt so offended that he tried to sue Behrendt, but the judge dismissed his case since in Germany satire is protected by the freedom of speech.

1969 was a particular controversy-heavy year for Behrendt. When in January of that year the German magazine Die Weltwoche put a critical Behrendt cartoon about Spanish dictator Franco on its cover, all issues were confiscated at the Madrid airport and Die Weltwoche was banned in the country for a while. The drawing in question depicted Franco putting a bull with the word "opposition" under the guillotine. In July, a cartoon of Franco raising prince Juan Carlos from a cabbage, also resulted in a ban when it appeared in the German magazine Der Tagesspiegel. In April 1969, the military junta in Greece ordered confiscation of the magazine Holland Herald, because of a cartoon of dictator Georgios Papadopoulos replacing a portrait of the Greek royal couple with a wedding photo of Aristotle Onassis and Jacqueline Kennedy. In January 1970, Der Tagesspiegel portrayed Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser as an avalanche victim, with Russian head of state Leonid Breznhev and Saudi king Faisal as two St. Bernhards with oil instead of brandy. The Saudi ambassador in Bonn protested at the German government, claiming the portrayal of king Faisal as a dog was lèse-majesté.

Over some of his cartoons, Behrendt later expressed regret. For decades, Romanian head of state Nikolai Ceaucescu was admired in the West for not always blindly obeying orders from the Soviet Union. Behrendt therefore always drew him as a sympathetic politician. But in 1989, Ceaucescu was deposed, put on trial and executed. It was revealed to the rest of the world that he had been a vicious dictator, responsible for the arrest, torture and deaths of thousands of his fellow citizens. Behrendt felt bad that he hadn't been able to see through Ceaucescu's façade. Later in his career, he also admitted that during the early decades of his career, he was less aware of the economics and behind-the-scenes operations behind most of international politics.

"Diplomatic torpedos". European heads of state fear Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs Vyacheslav Molotov.

Graphic and audiovisual contributions

On 5 May 1962, Fritz Behrendt joined his graphic artist colleagues at Algemeen Handelsblad in making a large group illustration. Among the other participants to this crossover drawing were Bouwk Denijs (from the section 'Voor U, Mevrouw'), Rupert van der Linden (artist of 'D. van Kwikschoten'), Raymond Bär & Jan van Reek (authors of the comic 'Wipperoen'), H. Focke ('Eigen Wijs'), Endre Lukács, H. Scholten, J. Mulder and Niek Hiemstra.

Fritz Behrendt contributed cartoons to publications by the Dutch environmental organization Milieudefensie, Amnesty International, the Evangelist Church of Germany and a foundation supporting widows of the 1995 Srebenica Massacre during the War in Former Yugoslavia (1991-1995). In 1985, he was one of several cartoonists to support Dutch comic artist Wim Stevenhagen, who was convicted for his refusal to fulfill his military service for reasons of principle. His and more graphic contributions were collected in the book 'Tegenaanval' (De Lijn, 1985). Starting in 1962, Behrendt was also a familiar face to Dutch TV viewers, presenting his "graphic commentary" in current event-related TV broadcasts.

Behrendt additionally designed the cover of a 1969 compilation record featuring New Years's comedy conferences by Dutch cabaret artist Wim Kan. Kan wrote him personal thanks, with the huge compliment: "(…) I have to say that me and my wife love your beautiful drawing. Though it is sad that if the sales of the record disappoint, we won't be able to say: 'Yes, but the cover wasn't good either.' People often ask: 'Where do you get your ideas?', but they never listen to the answer, what in your case should be: 'From my genius brain.' But, ah, you'll probably not say this about yourself. Can I therefore say it in your place?" Kan also mentioned specific Behrendt cartoons in his diaries, later made public in book form.

Behrendt also livened up the pages of some children's books, namely Làszló Hámori's 'De Gevaarlijke Reis' (De Arbeiderspers, 1962), Herman Koch's 'Marius Blok bij de Tommies' (1962) en A.M. Koppejan, e.a.'s 'Met Bus en Benenwagen', 'Ik en Mijn Fiets', 'Weten Maar Ook Doen' and 'Heb Je Naaste Lief' (all from 1971). He also wrote the foreword to his friend and colleague Oto Reisinger's retrospective book 'Amor... Amor' (1973).

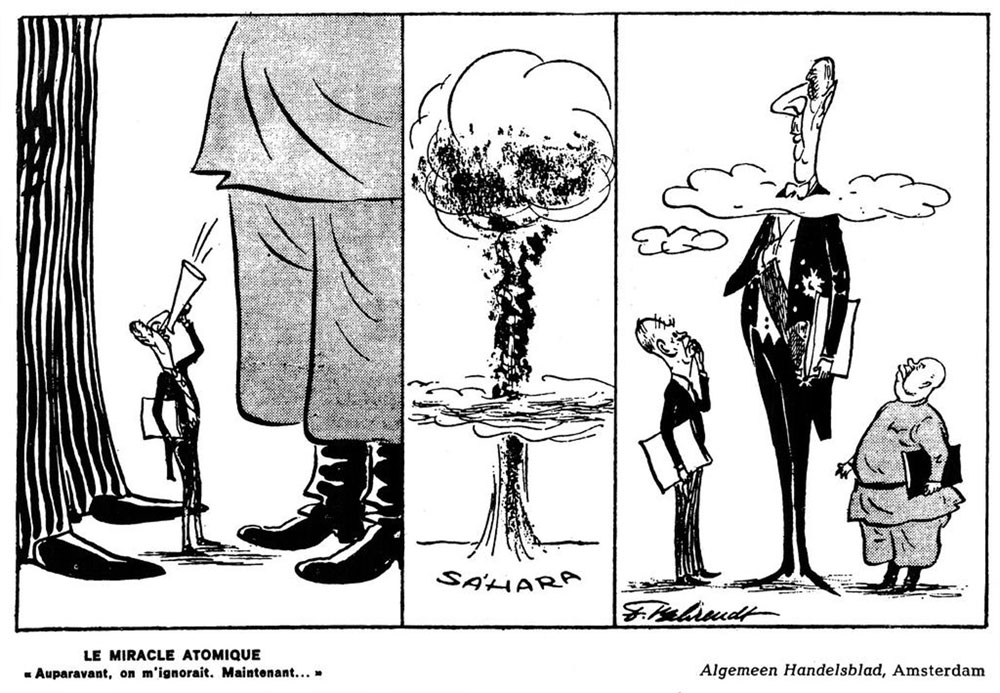

Cartoon about the first French nuclear test in 1960, which made France (caricatured as Charles de Gaulle) an atomic power on the level of the two other countries with atomic weapons: the U.S. (caricatured as Dwight D. Eisenhower) and Russia (caricatured as Nikita Khrushchev.) Algemeen Handelsblad, 1960.

Recognition

In October 1962, Behrendt received a letter from White House staff member Pierre Salinger, regarding a recent cartoon he drew about the Cuban Missle Crisis. At the time, Soviet missiles had been discovered in Cuba, leading to a diplomatic crisis between the USA and the USSR, that brought the world on the edge of nuclear escalation. Eventually, it was agreed that Russia would remove the missiles, while the U.S. would refrain from invading Cuba. In Behrendt's cartoon, Soviet leader Nikita Khruschev stands on John F. Kennedy's foot, but doesn't move, despite the U.S. President's requests. Only when Kennedy bursts out in anger, Khruschev is startled and instantly apologizes. According to Salinger, "President Kennedy most enjoyed the cartoon." When John Lennon and Yoko Ono released their 'Wedding Album' in 1969, the record contained various cut-out newspaper articles about their wedding, honeymoon, bag-in and bed-in peace activism, including cut-out editorial cartoons drawn by various British and Dutch comic artists, one of them was by Fritz Behrendt.

In 1967 and 1976, Behrendt won the award for "Best Political Caricature" at the International Cartoon Festival of Montreal. In April 1985, he received the Award for International Editorial Cartoons. He was named Officer in the Crown Order in Belgium (1975) and knighted in the Dutch Order of Oranje-Nassau (1995), while Austria bestowed him the Ehrenzeichen für Verdienste um die republik Österreich. The Croatian government gave him the Danica Hrvatke ("Dawn of Croatia"). In 2000, the United Nations honored him as "best political cartoonist" with the 2000 Ranan Lurie Political Cartoon Award, while in Germany he received the Gothaer Karikade Award for "Best Caricaturist". In 2002, Behrendt received the German honorary order Verdienstorde and was knighted in the Order of the Netherlands Lion. In 2006, he was awarded the Austrian "Ehrenzeichen für wissenschaft und Kunst" (Honorary Sign for Science and Art).

Behrendt was advisor of "political cartoons" at the University of Kent and the International Museum of Cartoon Art in the United States. In 1980, he was one of five political cartoonists whose work was exhibited in the Wilhelm Busch Museum in Hannover. Near the end of 2001, he had a solo exhibition in the House of History in Bonn, Germany. The Contemporary History Forum of Leipzig funded a traveling exhibition, 'A Feather for Freedom', about Behrendt. In the fall of 2009, his work was exhibited in the Dutch Resistance Museum in Amsterdam.

Death and legacy

In 2008, Fritz Behrendt died in Amsterdam at age 83. He remained active for De Telegraaf until the very end. His final cartoon was found on his drawing table and published the next day. Fritz Behrendt was admired by fellow political cartoonists like Brasser, Pat Oliphant and Gerard Alsteens (Gal).

Self-portrait, balancing various dictators on his pencil. On top Muammar Ghadaffi, being held by Kim Jong-Il. One row beneath appears Slobodan Milosevic, and in the row below Ayatollah Khatami, Saddam Hussein and Fidel Castro, with Augusto Pinochet beneath.