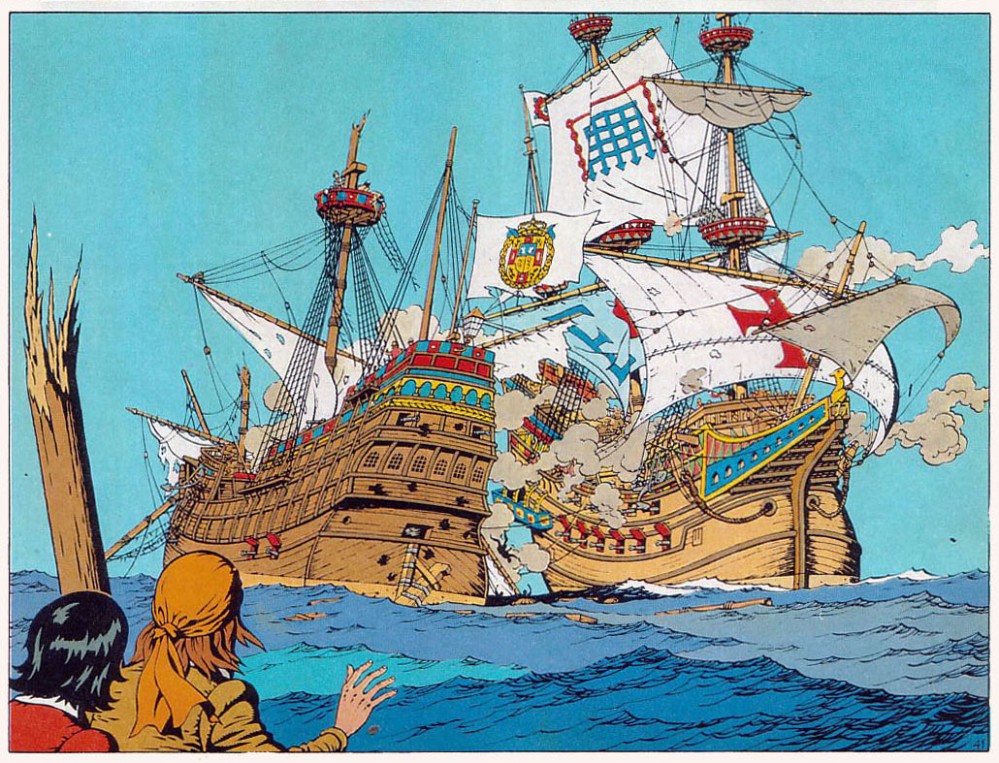

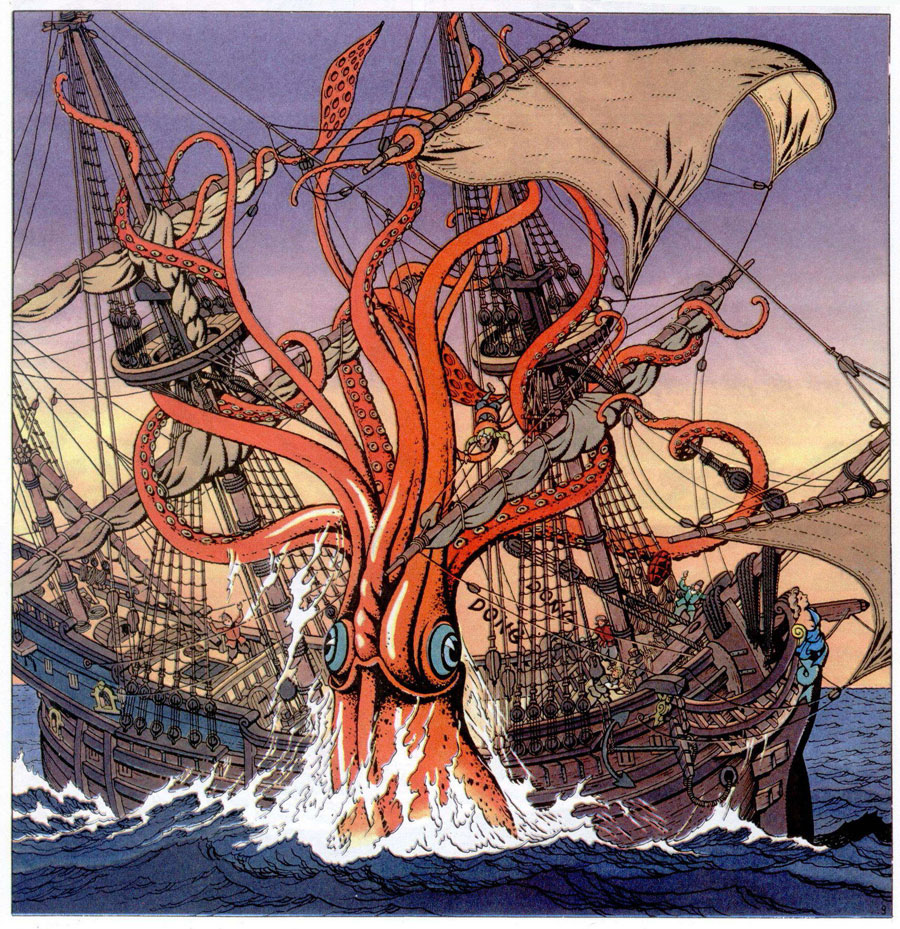

Cori de Scheepsjongen - 'De Onoverwinnelijke Armada'.

The Belgian comic artist Bob De Moor was one of the masters of the "Clear Line" drawing style, and a mainstay at Tintin magazine. For decades, he was one of the closest co-workers of Hergé, playing an important role in the artwork of the later 'Tintin' stories, as well as the reworkings of older ones. In between his tasks at Studio Hergé, De Moor worked on an impressive body of work of his own, easily switching between humorous and dramatic narratives. At first, his solo projects appeared in the Flemish press. De Moor was one of the main artists for the early Flemish comic weeklies Kleine Zondagsvriend, 't Kapoentje and Ons Volkske, for which he created a great many adventure serials and gag strips, notably the first version of 't Kapoentje's 'De Lustige Kapoentjes' (1947-1949). One of his most enduring newspaper comics was 'De Avonturen van Nonkel Zigomar, Snoe en Snolleke' (1951-1956) in Het Nieuws van den Dag. In the second half of the 1950s, De Moor began working exclusively for Tintin, where he combined his work at Studio Hergé with his own series. De Moor's first work for Tintin was his adaptation of the classic 1843 Hendrik Conscience novel 'De Leeuw van Vlaanderen' ('The Lion of Flanders', 1949). His further work included the gag comics 'Monsieur Tric' ('Meester Mus', 1950-1979) and 'Balthazar' (1965-1967), the adventure serials starring the actor 'Barelli' (1950-1989) and his masterpiece, the naval series 'Cori le Moussaillon' ('Cori de Scheepsjongen', 1951-1993). These 16th-17th century adventures of a young cabin boy sailing with the Dutch East India Company were a stunning and vivacious expression of De Moor's love for ships and the ocean. Loyal, dedicated and versatile, Bob De Moor also assisted Jacques Martin on his 'Lefranc' comic and provided the artwork for the final 'Blake & Mortimer' story by the late E.P. Jacobs, 'Les Trois Formules du Professeur Sato' (1989). Despite his personal creations, De Moor sacrificed most of his own career to his loyal service for Hergé. As a result, the general public is less familiar with his name than they could have been, while millions of readers have seen his artwork in 'Tintin' without even realizing it.

Cover illustrations for Tintin magazine, respectively issue #262 (29 October 1953) and #18 (1952).

Early life

Robert Frans Maria De Moor was born in 1925 in the harbor city of Antwerp. He was the second child in the family of Louis and Anna De Moor. His sister Alice was nearly eighteen years older, and would play an important role in the upbringing of her little brother. Father Louis De Moor (1882-1964) led an adventurous life. Early on, he had his own factory that designed and produced machines and tools, until World War I forced him to leave Belgium and seek shelter in London. Back in Belgium, he found employment with the Minerva car factory, but went bankrupt during the Great Depression of the 1930s. The De Moor family then ran a small cafe, where young Bob used to do his homework in a noisy atmosphere. As a child, his sister often took him on walks through the Antwerp harbor to watch the ships come in and leave again, fuelling the boy's lifelong passion for the sea.

Already as a child, De Moor adored maritime novels and pirate films, particularly those set in the 16th and 17th century. Daniel Defoe's 'Robinson Crusoë' and the movies 'Captain Blood' (1935) with Errol Flynn and 'Captain Courageous' (1937) with Spencer Tracy especially left a lasting impression. At home, he would fantasize his own naval stories, and familiarize himself thoroughly about historical ships, down to how they were exactly built and constructed. He eventually became such an expert that he was able to spot inaccurate details in the way ships were portrayed in Hollywood films and book illustrations. Another early interest was drawing. Reading comic magazines like Ons Volkske and later Robbedoes, the first comics that caught his attention were the translated publications of Rudolph Dirks' 'Katzenjammer Kids' and Martin Branner's 'Perry Winkle'. However, in his own artwork, he used to draw out historical scenes and stories based on the novels he read. It wasn't until 1947 before he discovered the 'Tintin' stories of Hergé, who became an important influence of his career, along with Edgar P. Jacobs and Willy Vandersteen.

World War II

Despite his naval interests, De Moor felt more for a career as an artist than as a sailor. In September 1940, during the Nazi occupation of Belgium, fourteen-year old De Moor enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp. While his parents urged him to study Architecture, he instead chose drawing from a model and eventually applied arts, which included caricatures and illustrations. In the summer of 1943, De Moor found employment with the AFIM animation studios, recently started by Ray Goossens and Jules Luyckx. Several other former Academy students followed as well, including De Moor's friends Marcel Colbrant and Mon van Meulenbroek, and the future comic creator Jef Nys. At AFIM, De Moor drew backgrounds for a short film with the folkloric 'Smidje Smee' character, and for 'Hoe Pimmeke ter Wereld Kwam', an original Goossens creation. When the studio chiefs refused to move their activities to the UFA studios in Germany, AFIM was dissolved. All staff under eighteen, including De Moor and his friends, were forced to work in the Erla factories in Mortsel near Antwerp, where Messerschmitt Bf 109 aircrafts were built and maintained for the Luftwaffe.

After the Liberation in 1944 brought peace back to Belgium, the AFIM studios were revived, re-employing De Moor and Marcel Constant, as well as De Moor's girlfriend at the time, Gilberte Ghesquiere. On 18 February 1945, Bob accompanied his girlfriend to her house, when a German V-bomb hit the street, severely injuring the young lovers. A piece of shrapnel cost him the middle and ring finger of his left hand. A second bombing near the hospital left both Bob and Gilberte unharmed, but their romance didn't last. On 3 August 1948, Bob De Moor married Jeanne De Belder, with whom he had five children: Chris (b. 22 September 1949), Dirk (b. 19 January 1952), Johan (b. 17 October 1953), Annemie (b. 18 December 1958) and Stefaan (b. 11 September 1963).

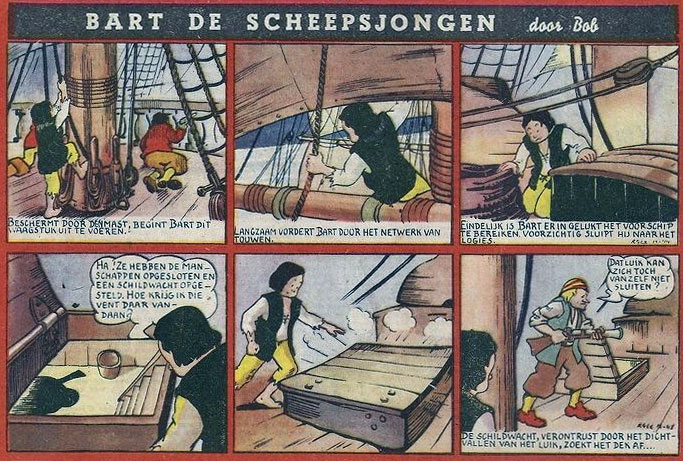

'Bart De Scheepsjongen' (Kleine Zondagsvriend, issue #22, 1945). The earliest incarnation of De Moor's thematically similar, but graphically revised nautical series 'Cori De Scheepsjongen' ('Cori Le Moussaillon').

Early comics: Kleine Zondagsvriend and more

Even though the AFIM studios had closed its doors for good in September 1945, and he had lost two of his fingers, this didn't keep Bob De Moor from further pursuing his career in arts. Shortly after the war, he began a steady production of comic strips for the Flemish press. Through his former AFIM bosses, Ray Goossens and Jozef Luyckx, he got a spot in the recently launched children's magazine Kleine Zondagsvriend (KZV), which was just expanding its pages to include more comics. For a maritime lover like De Moor it came as no surprise that his first comic strip, 'Bart de Scheepsjongen' (1945-1946), followed the adventures of a cabin boy in the late 16th century. Debuting in March 1945, the comic was published in issues #11 through #49. Created in a semi-realistic drawing style and published in varying formats (a full page, half a page or a strip), the 'Bart' comic still followed a naïve narrative while the artwork lacked professional skills. Over the course of the 1940s, De Moor gradually fine-tuned his craft, while experimenting in styles and genres, and signing with only his first name, "Bob", and later also with his initials "RDM".

'De Nieuwe Avonturen van Professor Hobbel en zijn assistent Sobbel'.

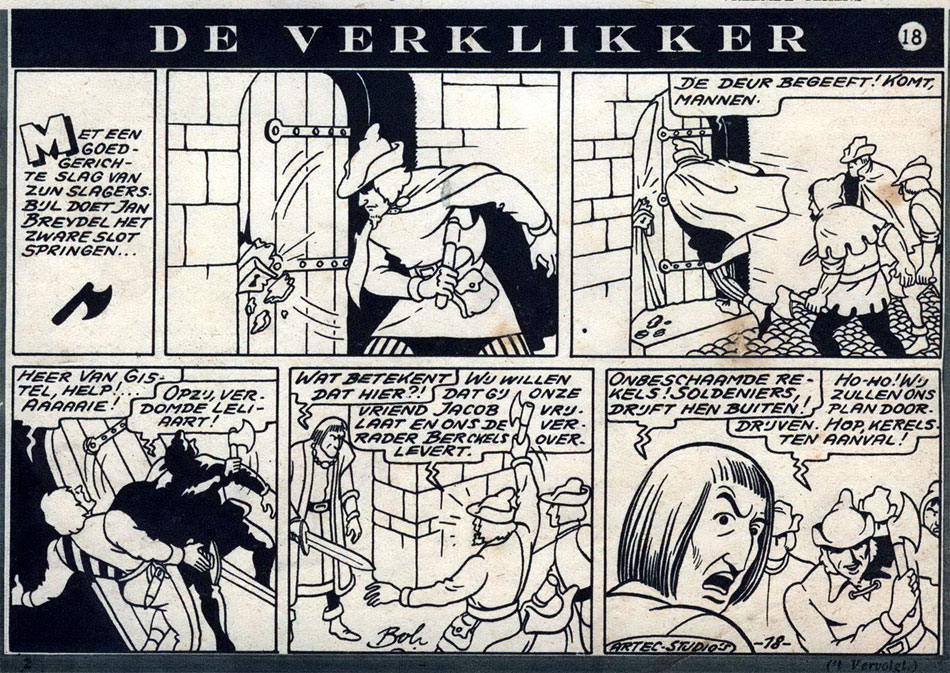

In late 1946, De Moor created a second feature for Kleine Zondagsvriend, this time in a cartoony style. 'Hobbel en Sobbel' (1946-1950) presented the surreal adventures of an absent-minded professor and his bumbling assistant, involving elements from science fiction to fairy tales and from cowboys to chivalry. For his two adventures starring private investigator 'Inspecteur Marks' (1946-1947), De Moor found inspiration in film noir, creating realistic artwork with moody scenes in the Antwerp harbors. Some episodes of the comic had fill-in art by Jules Luyckx (AKA Julux). His next feature, 'De Lotgevallen van Hannes Boegspriet' (1946-1947), was more humorous and followed the adventures of another sailor boy with a group of pirates. With writer Jozef van Overstraeten, chairman of the Flemish Automobile Association, De Moor created the serial 'Dat Wondere Pimpeltje' (1948). His final new comic strip for KZV was the one-shot story 'De Verklikker' (1949-1950), a historical tale set in the city of Bruges in 1302, as a prelude to the Battle of the Golden Spurs.

'De Verklikker' (Kleine Zondagsvriend, #13, 1950).

Artec-Studio's

Within no time, the assignments piled up for De Moor. He regularly provided illustrations and cartoons to the weekly magazines ABC and De Zondagsvriend. Another magazine, Week-end, ran his pantomime gag strips 'Professor Quick in Actie' (4 May 1947-20 January 1952) and 'De Lotgevallen van Babbel & Co' (13 February 1949-November 1950). For the newspaper De Nieuwe Gids, he made the full-page family humor comic 'De Lotgevallen van de Familie Kibbel' (10 November 1947-28 June 1948), as a replacement for Willy Vandersteen's similar 'Familie Snoek' comic. Between 1946 and 1949, the weekly magazine De Zweep published De Moor's pantomime strips 'Vodje de Zwerver', starring a hobo, and 'De Lotgevallen van Kareltje', about an unlucky bourgeois.

'Vodje de Zwerver' (22 September 1946).

To keep up with the workload, De Moor began a partnership with his brother-in-law John Van Looveren, operating as the Artec-Studio's. While Van Looveren provided some story ideas, he was mainly acting as an agent and took care of acquiring assignments. As De Moor had to secure full production, additional artists assisted on the artwork when necessary, including De Moor's Art Academy friend Armand van Meulenbroeck and presumably also François Cassiers, who later formed the Flemish comedy duo De Woodpeckers with his brother Jef. The first joint production by De Moor and Van Looveren was 'Le Mystère du Vieux Château Fort' (1947), a Disneyesque fairy tale story published directly in book format, and exclusively in French, by Éditions Campéador. Starting in 1948, all new creations began carrying the "Artec-Studio's" credit. Van Looveren took his task seriously. By 1949, Bob De Moor had 17 ongoing comic features in newspapers and magazines. Several stories were later resold to other publications. In addition, De Moor made political and sports caricatures for Het Handelsblad.

Debut episode of 'De Lustige Kapoentjes' (November 1949).

De Lustige Kapoentjes

Starting in 1947, an important new homebase for Bob De Moor's comics was 't Kapoentje, a children's supplement edited by Marc Sleen for the newspaper De Nieuwe Gids (and later Het Volk). During the title's early months (April-November 1947), the magazine's flagship comic feature had been Willy Vandersteen's 'De Vrolijke Bengels' (1946-1954). This gag comic starred four kids performing pranks and counter-pranks on a bumbling police officer and a youngster hoodlum. The plots are often set in motion when an elderly woman's cakes are stolen by the youngster hoodlum, giving the kids a reason to get revenge on him. When in November 1947 Vandersteen left 't Kapoentje to join Ons Volkske, he took his comic with him. To fill the gap, 't Kapoentje asked Bob De Moor to create a substitute, following the same concept.

Naming the new comic 'De Lustige Kapoentjes' ("The Jolly Rascals"), the artist redesigned the cast and gave them different names. The child protagonists were now named Petrus (the leader of the gang, who has a huge quiff), Janus (the tall one, with glasses), Bertus (the short one with the beret), Eefje (the girl) and Benjamien (her kid brother). The police officer was fittingly named Pakker (literally meaning "Grabber"), the older woman became Mie Vis and the hoodlum was renamed Dorus. In 't Kapoentje's French-language edition Le Petit Luron, 'De Lustige Kapoentjes' ran as 'Les Joyeux Lurons'. In 1950, De Moor's 'De Lustige Kapoentjes' was reprinted in the newspaper De Nieuwe Gazet, under a different title, 'Petrus en zijn Rakkers'.

When in December 1949, De Moor also left 't Kapoentje, Marc Sleen continued 'De Lustige Kapoentjes' from 9 February 1950 until April 1965. Over the next couple of decades, until the cancellation of 't Kapoentje, the comic was continued by several different artists who all redesigned and renamed the main cast members: Jef Nys (1965-1966), Hurey (1966-1976) Karel Boumans (1976-1985) and finally Jo (1985-1989). Between 1965 and 1974, Sleen, aided by his assistants Hurey and Jean-Pol, simultaneously revived his version of the comic in Pats, the children's supplement of the newspaper De Standaard. Since they couldn't use the copyrighted title 'De Lustige Kapoentjes', these gags were always printed without a title. In 2011, after a long absence, 'De Lustige Kapoentjes' made a brief comeback, this time drawn by Tom Bouden, with a different scriptwriter for each gag.

't Kapoenje: realistic serials

Almost simultaneously with the creation of 'De Lustige Kapoentjes', De Moor and Artec-Studio's also provided 't Kapoentje with the medieval story 'Willem de Vrijbuiter' (26 November 1947-7 October 1948). From the fifth episode on, the feature was retitled 'Willem Koelbloed', and under this title it was also reprinted in De Volksmacht in 1949-1950. Set in 1302, the plot follows a brave and strong Flemish resistance fighter who battles the French oppressors, eventually joining uprisings like the 'Brugse Metten' ('Matins of Bruges') and the 'Guldensporenslag' ('Battle of the Golden Spurs'). The story was clearly influenced by the 1843 classic Hendrik Conscience novel 'De Leeuw van Vlaanderen' ("Lion of Flanders"), which romanticized the same historic events. The 'Willem Koelbloed' serial can be considered a predecessor to De Moor's more ambitious 1949 comic adaptation of Conscience's 'De Leeuw van Vlaanderen' in Tintin magazine.

Between 1947 and 1950, Bob De Moor drew various other realistic comics for 't Kapoentje, but also for Overal, the adult supplement of the newspaper De Nieuwe Gids. Under the pen name Bob Van Looveren, De Moor launched 'De Dodende Wolk' (November 1947-1948), a gripping serial about a looming world war and a mad professor with an all-destroying cloud as a weapon. It first appeared in Overal, and later also ran in 't Kapoentje (1950-1951). Its follow-up 'De Vergeten Stad' (1948-1949) began publication in Overal, but was after four episodes transferred to 't Kapoentje. For 't Kapoentje, De Moor additionally created the Belgian western 'Het Land Zonder Wet' (14 October 1948-28 April 1949) and the historical comic 'De Slaven van de Keizer' (1949-1950). Together with the journalist Gaston Durnez, De Moor created 'De Koene Edelman (of het Bewogen Leven van Jan Baptist Messire de la Salle)' (1949), a comic biography of the French priest Jean-Baptiste de La Salle (1651-1719), founder of the Institute of the Brothers of the Christian Schools.

'De Rosse', by Artec Studio's.

't Kapoentje: comical features

In addition to serious adventure serials, De Moor also created several cartoon duos in 't Kapoentje, using art that, for the first time, demonstrated his Clear Line influences. Both the text comic 'Monneke en Johnneke' (29 April-9 September 1948) and the two stories of 'Janneke en Stanneke' (September 1948-1949) followed improvised storylines with absurd twists and deus ex machina solutions. A similar comic was 'Bloske en Zwik' (1948-1949), of which two serials appeared: 'Bloske & Zwik detectives' (16 December 1948-28 April 1949) and 'Het Eiland der Reuzen' (1949). Among De Moor's further comical work for 't Kapoentje are the pantomime gag strip 'De Rosse', about a red-haired boy (1 April 1948-10 February 1949) and the adventure serials 'De Slaapmachine van Jonas' (6 January-28 April 1949), 'Het Halssnoer met de Groene Smaragd' (1949-1950) and 'De Tijdmachine van Carolus Clem' (1949-1950). On top of all that, De Moor provided the artwork for the readers' drawing course, 'Onze Kleine Tekenschool' (1949). Another Artec production, two adventures of 'Tim en Tom' (1949-1951), were presumably drawn by Mon Van Meulenbroeck .

Reprints

After their initial publication in 't Kapoentje, many of De Moor's comics were reprinted in other newspapers. Starting in November 1948, several serials reran in the newspapers De Nieuwe Gazet (not to be confused with De Nieuwe Gids) and Het Wekelijks Nieuws: first 'De Dodende Wolk' (1948-1949), then 'Het Land Zonder Wet' (1949-1950) and finally also the gag strip 'Petrus en zijn Rakkers' (1950), which was 'De Lustige Kapoentjes' under another title. In 1953, De Volksmacht also ran 'Het Land Zonder Wet'. In 1952, 'Bloske & Zwik detectives' was reprinted in Het Wekelijks Nieuws, and then released in book format by the paper's publisher, Sansen. This first 'Bloske en Zwik' story also appeared in Het Volksweekblad (1 January-31 December 1955), while the second one had been reprinted in Het Handelsblad (1949-1950). 'De Slaapmachine van Jonas' was also published in Het Handelsblad (1950) and in Het Wekelijks Nieuws (1960). Het Volksweekblad also printed De Moor's 'De Slaven van De Keizer' (1951) and 'Het Halssnoer met de Groene Smaragd' (1954). During the 1960s, 'Janneke en Stanneke' (1960), 'Het Eiland der Reuzen' (1962) and 'De Vergeten Stad' (1964) were reprinted in Pum-Pum, the juvenile supplement of Het Laatste Nieuws.

Le Lombard: Ons Volkske & Kuifje

In late 1948, De Moor got in touch with Karel Van Milleghem, chief editor of Kuifje, the Dutch-language edition of Tintin magazine. A key figure at Éditions du Lombard, Van Milleghem was also responsible for providing many of the comics in Ons Volkske, a Flemish children's magazine that was in a way a "budget edition" of Kuifje. Besides rerunning comics from Tintin, Ons Volkske also featured original material, and De Moor was hired to provide it. Van Milleghem also secured the artist a steady income by having him work two days a week at Tintin's layout department in Brussels, assisting the graphic designer Evany. In this role, De Moor did design work and spot illustrations, for instance for the editorial section 'Tintin Vous Parle' ('Kuifje aan het woord', in Dutch). With these new opportunities, he was able to drop most of the exhausting Artec-Studio's activities. A dispute and court battle followed with his brother-in-law and business partner John Van Looveren, who sued De Moor for breach of contract. The matter was settled in 1950, with De Moor finishing the ongoing assignments, but not taking on new ones. With a staff position at Tintin's art department, and later at Studio's Hergé, De Moor was able to start a new phase in his career, where quality prevailed over quantity.

'Mieleke en Dolf' (Ons Volkske, 4 January 1951).

Starting off in the first issue of the new rendition of Ons Volkske, on 13 January 1949, De Moor was present with the one-shot serial 'Het Wonderschip' ("The Wondership", 1949), a story about the stolen plans of a technically ingenious ship. While this first story tackled De Moor's favorite subject, the sea, his second serial for Ons Volkske was a space saga: 'Oorlog in het Heelal' ("War in the Universe", 1949-1950). Between 13 January 1949 and 12 July 1951, he also provided the magazine with the gag strip 'De Avonturen van Mieleke en Dolf', starring two kid brothers. These strips were also printed in the French magazine Chez Nous as 'Les Farces de Titi et de Toto'. Later in 1949, De Moor created a similar gag comic for both Kuifje and Tintin, starring a thin and a fat kid, under the respective titles 'Fee en Fonske' and 'Bouboule et Noireaud' (1949-1951). These gags also appeared in the weekly magazine Ons Volk and its French edition Chez Nous (as 'Les Farces de Titi et de Toto').

In both Ons Volkske and Kuifje, De Moor also illustrated many weekly text stories written by Gommaar Timmermans, several involving characters from Flemish folklore, but also Ons Volkske's long-running naval adventure serial 'De Dobber, Ahoy!'. By 1950, Bob De Moor had completely switched to Tintin magazine, and Ons Volkske began to reprint his stories from that magazine.

De Leeuw van Vlaanderen (The Lion of Flanders)

Shortly after his debut in Ons Volkske, chief editor Karel Van Milleghem also brought De Moor to Kuifje, and eventually also the French-language parent magazine Tintin. To boost the sales of Kuifje in the Dutch-speaking regions, De Moor was asked to create a story that would appeal to Flemish readers. As a subject, he chose Hendrik Conscience's 1838 historical novel 'De Leeuw van Vlaanderen' ('The Lion of Flanders'), a romanticized account of the Battle of the Golden Spurs (1302), when Flemish troops won a victory over the French armies. At the time of its original release, Conscience's novel helped revive interest and pride in this almost forgotten medieval event. His book became a bestseller and the battle date itself (11 July) a national holiday for the Flemish community.

Between issues #37 of 1949 and #50 of 1950, the story ran exclusively in Kuifje magazine, and was eventually also serialized in Ons Volkske. Since the original book was such an important influence on Flemish nationalism and had French nobility as major villains, the comic adaptation did not appear in the French-language parent magazine Tintin. However, in issue #30 of 1950, a battle scene from De Moor's comic appeared on the magazine cover. Since Kuifje and Tintin always had the same cover, it also appeared on the Walloon edition. For this issue, scriptwriter Yves Duval was brought in to write a text story about the 14th-century Breton military hero Bertrand du Guesclin, while the artwork on the cover was amended: the Flemish lion flag became Du Guesclin's coat of arms. Meanwhile, De Moor's 'De Leeuw van Vlaanderen' was well-received by Flemish readers, partially due to the fact that the majority were familiar with Conscience's novel, but also because De Moor's vivid, high-quality artwork enriched the story.

While De Moor's version of 'The Lion of Flanders' is considered a classic today, he wasn't the first to adapt this novel into a comic story. Already in 1934, Eugeen Hermans had done the same. Around the same time De Moor's adaptation was serialized, an artist named Wik published another comic book version of 'De Leeuw van Vlaanderen' in rival magazine Robbedoes. De Moor also wasn't the last comic artist to translate Conscience's classic novel into a comic strip: Buth, Jef Nys, Gejo, Karel Biddeloo, Christian Verhaeghe and Ronny Matton all did the same. Willy Vandersteen was so impressed by De Moor's version that he also decided to make a realistic comic adaptation of a classic Flemish nationalist novel, 'Tijl Uilenspiegel' (1951-1953). As they had become good friends, De Moor helped him with some of the artwork (as he had also done with some of the more complicated scenes in Vandersteen's 'Suske en Wiske' stories for Tintin). Another Flemish artist, Buth, was in such awe over De Moor's 'De Leeuw van Vlaanderen' that he plagiarized several images for his own 1950 text comic version.

In 1952, 'De Leeuw van Vlaanderen' was published in book format by Standaard Uitgeverij, the first major comic book release of De Moor. While the original story was printed in black-and-white, a colorized version was published later. In 1976, Michel Deligne finally published 'De Leeuw van Vlaanderen' in a French-language translation.

Further Flemish heroes

As a follow-up to 'De Leeuw van Vlaanderen', editor Karel Van Milleghem and De Moor wanted to adapt another Flemish literary classic. Their top choice was Constant de Kinder's 1910 youth novel about 'Jan zonder Vrees', but this was still copyrighted. Instead, De Moor created a hero of his own, a medieval strongman called 'Sterke Jan' (1951-1952). Besides appearing in Kuifje and Ons Volkske, this time the story also ran in Tintin, under the title 'Conrad le Hardi'. Unlike its folkloric inspiration Jan Zonder Vrees, De Moor's hero was far more sillier and the story's overall tone more comical. In one scene, the hero hangs all of his opponents to the city gate by their belts as if they are a bunch of clothes left out to dry.

In the following year, De Moor adapted another Hendrik Conscience novel, this time 'De Kerels van Vlaanderen' (1871). Serialized in Kuifje and Ons Volkske in 1952 and 1953, the story centers around a group of Flemish rebels who rise against count Charles the Good in 1126-1127. While certainly epic, 'De Kerels van Vlaanderen', was a bit more nuanced, with heroes who aren't all incorruptible. Just like 'De Leeuw van Vlaanderen', this serial only ran in the Flemish edition of the magazine, while Tintin printed a translation of one of Bob De Moor's newspaper comics.

'De Nieuwe Avonturen van Tijl Uilenspiegel' - 'Het Vals Gebit' (Het Nieuws van den Dag, 15 November 1950).

Tijl Uilenspiegel

By 1950, De Moor had a steady homebase at Éditions du Lombard. And while he had burned many bridges when leaving the Artec-Studio's, he remained active for the Flemish press for most of the 1950s. In 1950, he joined the newspaper Het Nieuws van den Dag, which had just lost its popular comic feature 'Nero', by Marc Sleen, to the newspaper Het Volk. Het Nieuws van den Dag's initial replacement comics were Raf Van Dijck's 'Kwik en Filidoor' and Lucien De Roeck's 'De Strijd Om Het Uranium', but they didn't catch on. On 22 May 1950, Bob De Moor's 'De Nieuwe Avonturen van Tijl Uilenspiegel' kicked off, and proved more popular with readers. The stories feature the 16th-century Flemish folk hero Tijl Uilenspiegel and his sidekick Lamme Goedzak, but then in different time periods, mostly the present.

In the debut episode, both heroes are in Heaven, and ask Saint Peter permission to return to earth. Their request is denied, but the two scoundrels take the parachutes of two deceased soldiers and descend. Some stories, like 'Het Vals Gebit', contain Flemish-nationalist propaganda, criticizing the post-war repression of Nazi collaborators, the 1946 bombing of the Yser Tower and the forced abdication of king Leopold III. In total, four 'Tijl Uilenspiegel' stories ran in Het Nieuws van den Dag, until the final episode was printed on 14 August 1951. The series also appeared in sister papers 't Vrije Volksblad, De Nieuwe Gids and De Antwerpse Gids.

'Nonkel Zigomar, Snoe en Snolleke'.

Snoe en Snolleke (Johan en Stefan)

In the final panels of De Moor's fourth 'Tijl Uilenspiegel' story, two kids were among the people dropped from a covered wagon. They turned out to be the heroes of the next comic feature in Het Nieuws van den Dag and its sister papers, debuting on 16 August 1951. 'De Avonturen van Nonkel Zigomar, Snoe en Snolleke' became the longest-running series of Bob De Moor's career, starring the adventures of two boys and their uncle. Uncle Zigomar is a gardener who hails from Antwerp. Much like Willy Vandersteen's Lambik and Marc Sleen's Nero, he is an easily agitated, naïve, clumsy, vain but well-meaning twit. Usually, the blond quiffed Snoe and his younger, black-haired brother Snolleke solve all the problems.

During the time he worked on this newspaper strip, De Moor was already employed by Studio Hergé, where all the artwork had to look perfect, down to the tiniest details. For De Moor, creating 'Snoe en Snolleke' was a way to let off steam after work hours. The drawings still looked neat, but were more loose in their execution, while the stories were mostly improvised. In four-and-a-half years time, De Moor managed to churn out 15 stories. Yet despite this large quantity, only four were made available in album format by N.V. Periodica at the time. The final episode concluded in the papers on 29 February 1956, as De Moor's workload at Hergé's studio had become too much.

In 1959, De Moor created the one-shot serial 'De Zoetwaterpiraten' ('Pirates d'Eau Douce') for Tintin, starring the characters 'Mik, Dik en Vik'. While the tale featured brand new characters, storywise it could just have been another 'Snoe en Snolleke' adventure.

'Johan en Stefan' #3 - 'De Schele Zilvervos' (colorized version of the 'Snoe en Snolleke' newspaper strip).

Between 1978 and 1984, other 'Snoe en Snolleke' stories were finally made available in book format when publisher De Dageraad released them in the 'Magnum' series. Thanks to enthusiastic collectors, the titles sold well. In 1987, De Moor rebooted the series after a thirty-year hiatus. The older stories were colorized, Flemish dialect was changed to standard Dutch and certain panels redrawn with assistance from Geert De Sutter. The series was retitled as 'Johan en Stefan', after two of De Moor's sons, and serialized in Gazet van Antwerpen. New book collections were published in Dutch and French by Casterman and even translated into Portuguese.

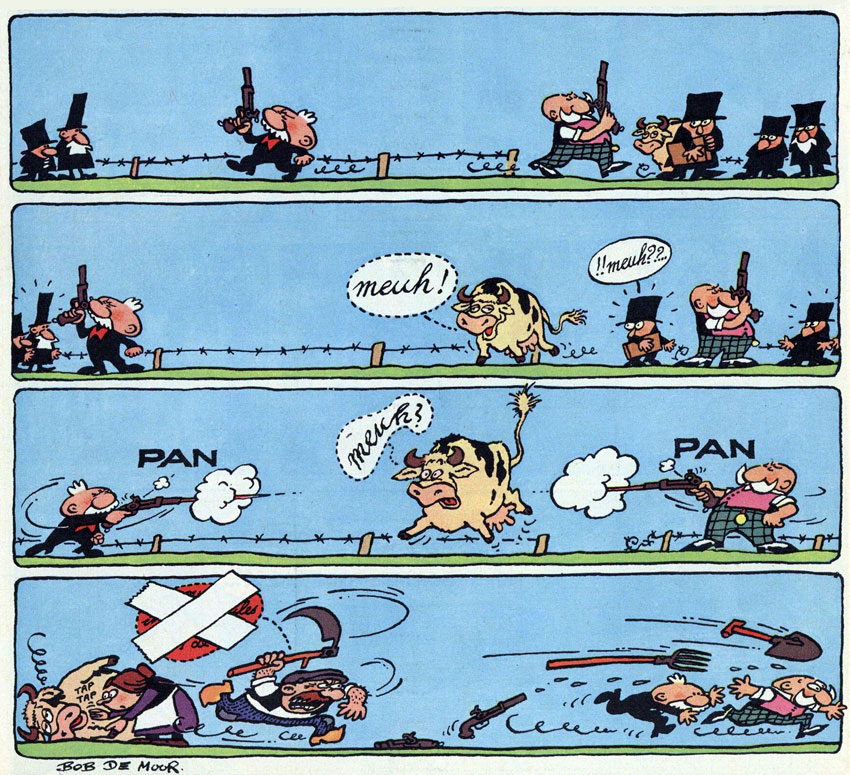

Meester Mus

In the meantime, De Moor's presence in Tintin increased. In addition to 'Bouboule et Noiraud', he created another humor comic, 'Professeur Tric', later renamed to 'Monsieur Tric' ('Meester Mus' in Dutch, 1950-1979). Tric is a well-meaning, but clumsy school teacher who looks like a cross between Charlie Chaplin and Willy Vandersteen's Lambik. Debuting in the 23 February 1950 issue of Tintin, he appeared both in short gags and adventures of four pages in length. René Goscinny wrote the scripts for nine short stories in the period 1957-1958. Appearances became more and more sporadic, as De Moor saw the comic as a funny pastime. In 1983, the final episode appeared in the 21st Super Tintin Spécial. Between 1952 and 1958, gags of 'Meester Mus' were reprinted in Ons Volkske too.

'Balthazar' (Tintin #52, 1966).

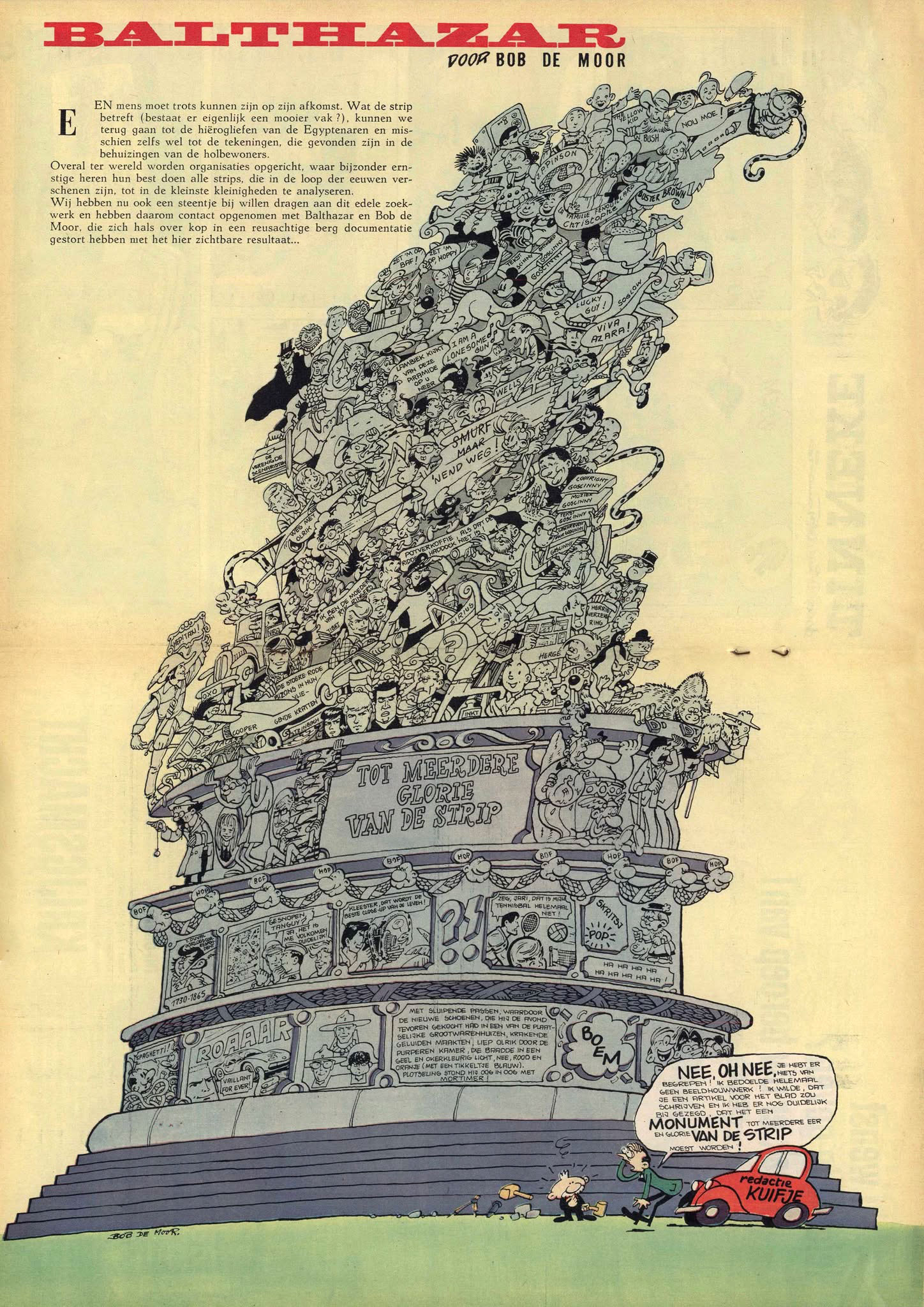

Balthazar

Between 1965 and 1967, De Moor created another gag strip for Tintin, 'Balthazar'. The first gag of this pantomime comic ran in issue #28 of 1965 (13 July). Originally intended as a brother of Monsieur Tric, Balthazar is a little man in a black suit with a white mustache. One gag even featured a younger brother, Melchior. Inspired by Mad Magazine, De Moor used a more absurd, cynical kind of comedy and cartoony style. He deliberately tried to draw "bad", without any regard for perspective or perfect anatomy. The free-spiritedness of 'Balthazar' was much to De Moor's liking and Hergé and chief editor Michel Greg supported the comic strip. Yet for the average Tintin reader, 'Balthazar' looked too "slovenly and sloppy". Several readers complained that this "badly drawn comic" didn't belong in the pages of their favorite magazine, so after two years, 'Balthazar' was discontinued, with the final gag appearing in issue #48 of 1967 (30 November). Still, De Moor kept using Balthazar in merchandising promoting 'Tintin' magazine and its comics. He also snuck in Balthazar's face on a balloon during the carnival scene in Hergé's 'Tintin and the Picaros'.

'Barelli Op Nusa Penida' episode #1 - 'Het Tovenaarseiland' (1951).

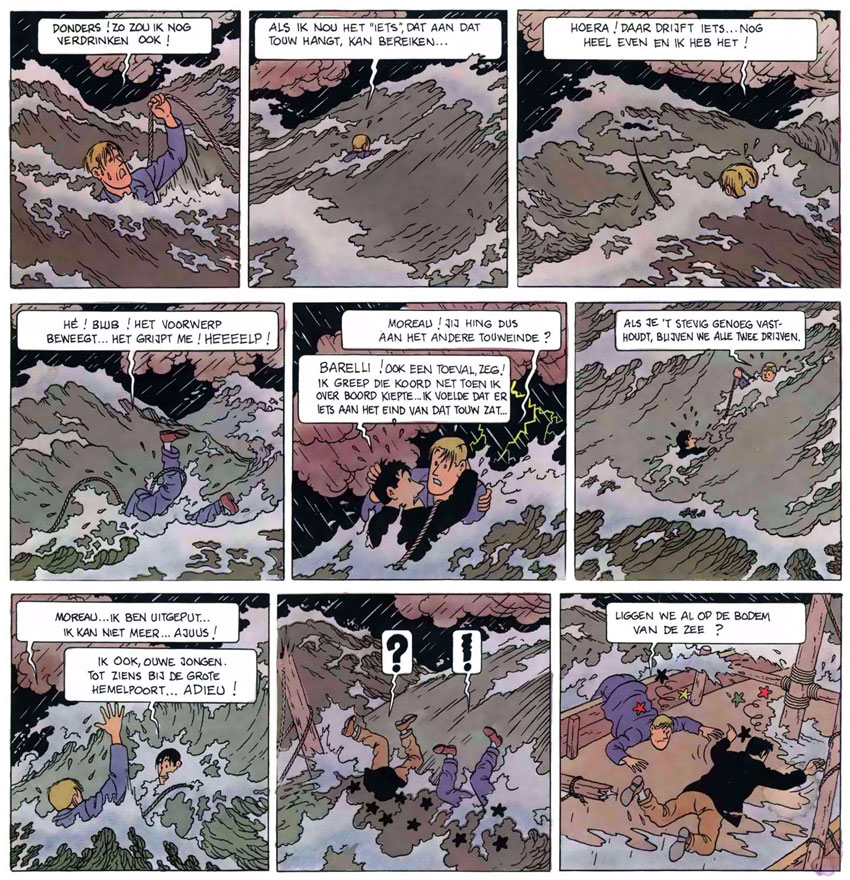

Barelli

Still in 1950, De Moor created one of his best-known heroes. Around that time, Tintin was trying to increase its sales in France by releasing a French edition of the magazine. To appeal to that readership, De Moor was assigned to create a comic serial set in Paris, resulting in 'L'Énigmatique Monsieur Barelli' ("The Enigmatic Mister Barelli", 1950-1951). Based on an initial story idea by presumably Jacques Van Melkebeke, the first episode appeared in the 27 July 1950 issue of Tintin. The main hero is Georges Barelli, a theatrical actor of Yugoslavian descent, whose uncle Vittorio is head of a theatrical company. With the bespectacled aunt Sofie and Barelli's black-curled love interest Anna Nannah, the comic was notable for its strong female cast.

Drawn in a Clear Line style in the tradition of Hergé and Jacobs, Barelli is comparable to Tintin, not just because of his quiff, but also because his actual profession is closer to being a private investigator. He regularly gets involved in all kinds of criminal situations which he tries to solve, often thanks to his many disguises. Barelli's best friend is the journalist-paparazzo Randor, and he can also count on the pipe-smoking Parisian police inspector Moreau, who, in the Dutch-language version, mixes French and Dutch words in his speech.

'Barelli en de Boze Boeddha' (1972).

In 1951 and 1952, Mister Barelli starred in two new adventures, but after that, his appearances became more sporadic. It took over ten years for a new story ran in Tintin, as the character returned in 1964, 1968, 1972, 1974, 1976, 1979, 1981 and 1989. Appearing directly in book format, the 1989 episode 'Bruxelles Bouillonne' (''Barelli in Bruisend Brussel') was a special story, made by commission of the Flemish Community. The comic book shows several tourist hotspots in Brussels, with cameos for some well-known Brussels people, like jazz musician Toots Thielemans, flamboyant policeman François "Susse" Rowies (known for his funny gesticulations while guiding the traffic) and Guy Dessicy, head of the Belgian Comic Strip Center. During the making of the album, De Moor was assisted by his son Johan De Moor and assistant Geert de Sutter. The book was also translated into English, German and Spanish.

Cori de Scheepsjongen - 'Koers Naar Het Goud'.

Cori de Scheepsjongen

As 'Barelli' was intended for Tintin's French readers, in 1951 De Moor was asked to create a comic targeting the readers in the Netherlands. This became the comic series many consider his greatest achievement, 'Cori De Scheepsjongen' ('Cori Le Moussaillon', meaning "Cori the Cabin Boy"). Already in 1945, he had drawn a serial about a young 16th-century cabin boy in Kleine Zondagsvriend, 'Bart de Scheepsjongen'. For his new creation, De Moor rebooted the concept and the main character, but changed his name, and featured more realistic and detailed artwork. Debuting in the 19 July 1951 issue (#38) of the Belgian edition of Tintin, 'Cori De Scheepsjongen' is set in the mid- to late 16th-century and follows the adventures of Cori, an orphan boy who is kidnapped by pirates, but rescued by the Dutch East India Company, after which commander Harm Janszoon adopts him. As a cabin boy, he joins the Company on their exploration journeys.

The vivacious adventure stories are filled with sea battles, treasure hunts and provide readers with a well-documented time capsule of nautical life during the heydays of exploring. Cori gets involved in battles against the Spanish Armada and the Eighty Years' War between the Netherlands and Spain. His travels bring him to exotic continents such as South East Asia, Africa, America and the Arctic, while he also meets real-life historical naval officers like Pieter van der Does, Joris van Spilbergen, Willem Janszoon, Piet Heyn and explorers like Willem Barentsz. Above all, 'Cori de Scheepsjongen' is a breathtaking showcase for De Moor's expertise in depicting caravels, galleons and other kinds of vessels down to the tiniest details.

In 1951 and 1952, the first serial of 62 pages ran under the title 'Onder De Vlag van de Compagnie' ('La Compagnie des Grandes Indes'). It wasn't until his workload at Studio's Hergé slowed down before De Moor returned to the character. Using even more documentation and a slightly older Cori, the second story 'De Onoverwinnelijke Armada' ('L'Invincible Armada') took off in the 22 November 1977 issue of Tintin, while the Dutch-language version appeared in the comic magazine Eppo. Widely praised as "the comeback of Bob De Moor" after years of anonymous work for Hergé, the artist moved on to create new 'Cori' stories during the 1980s, which this time appeared directly in book format at Casterman. Following the second volume of 'De Onoverwinnelijke Armada' (1980) was 'Koers Naar Het Goud' (1982), which was a redrawn and colorized update of the first 1950s serial. In 1987, De Moor created a genuine new story, 'De Gedoemde Reis' ('L'Expédition Maudite'), which received the Prix Jeunesse for children between the age of nine and twelve at the 1988 Comic Festival of Angoulême, France. His assistant on the later 'Cori' stories was Geert De Sutter. His son Johan de Moor finished 'Dali Capitain' (1993), the fifth and final story that his father had been working on, which was published posthumously.

Cori de Scheepsjongen - 'De Gedoemde Reis' (1987).

Studio's Hergé

Starting in February 1951, De Moor became a co-worker of Hergé, and by September 1955 had a fulltime job with Studio's Hergé in Brussels. For the occasion, the De Moor family moved from Wilrijk, near Antwerp, to the Brussels suburb of Uccle. De Moor managed to fill the gap left by Hergé's former assistant, Edgar P. Jacobs. Dedicated, modest and loyal, De Moor managed to closely approach Hergé's Clear Line, and quickly became his right hand man. He became responsible for most of the backgrounds in the 'Tintin' stories. In the early years of Studio's Hergé, the team consisted of Hergé, De Moor and colorist Guy Dessicy. Later, De Moor worked in a close collaboration with Jacques Martin, who also brought along his own assistants, Roger Leloup and Michel Demarets. Along with a group of colorists and administrative staff, the team assisted Hergé on the creation of new 'Tintin' stories, the reworking of older ones and the production of promotional material. In the final years of the studio's existence, Bob's son Johan De Moor also joined the team.

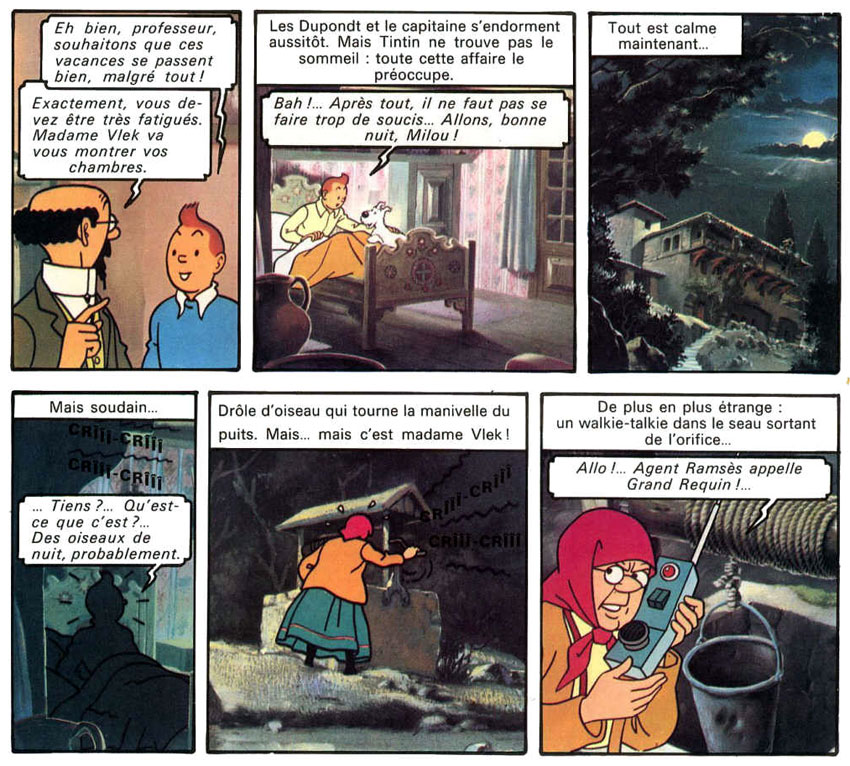

Bob de Moor was largely responsible for the modernization of the Tintin episode 'The Black Island'. ©Hergé/Moulinsart, 2012.

The first 'Tintin' story with Bob De Moor's collaboration was 'Destination Moon' (1950-1952). Among his most astonishing contributions are the moon rocket and lunar landscapes in 'Explorers On The Moon' (1952-1953), as well as his 1965 revision of 'The Black Island'. Hergé asked De Moor to redraw the backgrounds for this latter album at the request of the British publisher, who felt that the original 1936 book presented an outdated version of their country. De Moor traveled to Great Britain and made countless sketches of local architecture, landscapes and official uniforms. Together with Jacques Martin, De Moor also had a prominent role in the production of the 1950s/1960s 'Tintin' albums 'The Calculus Affair', 'The Red Sea Sharks', 'Tintin in Tibet' and 'The Castafiore Emerald'. For the final two installments created during Hergé's lifetime, 'Flight 714 to Sydney' (1966-1967) and 'Tintin and the Picaros' (1975-1976), Bob De Moor had an even larger role in the artwork, as Hergé was suffering from depression and the burden his iconic creation had become for him.

Work at the studio was laborious, but slow. Hergé strove for absolute perfectionism, and only deemed a page finished when he was fully satisfied. As a result, only eight full 'Tintin' stories were completed in 25 years time, and Tintin magazine ran for years without any appearance of its title character. Still, Studio's Hergé had enough work on its hands. As he most closely touched Hergé's style, Bob De Moor was involved with the studio's promotional art and commercial assignments through Lombard's Publiart division, and the animation projects of the publisher's Belvision studio. He provided artwork for Belvision's 1956 TV cartoons based on 'Tintin', and the backgrounds for the feature films 'Prisoners of the Sun' (1969) and 'Tintin and the Lake of Sharks' (1972). The full-color graphic novel adaptation of the latter story was also largely Bob De Moor's work.

'Tintin et le Lac aux Requins' ('Tintin and the Lake of Sharks') (adaptation from the movie, 1973).

Side projects during the Studio years

Since he was on the Studio's Hergé payroll, De Moor was able to secure a monthly income. As Hergé's closest co-worker, he was also allowed a small percentage of the royalties for the albums he had participated in. In turn, De Moor was also allowed to work on his own comics during work hours, with the largest part of the royalties going to the studio. Because there were longer periods of time without any new 'Tintin' stories, Bob De Moor was able to create new episodes of his 'Barelli' and 'Cori' comics during the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, all with full support of Hergé.

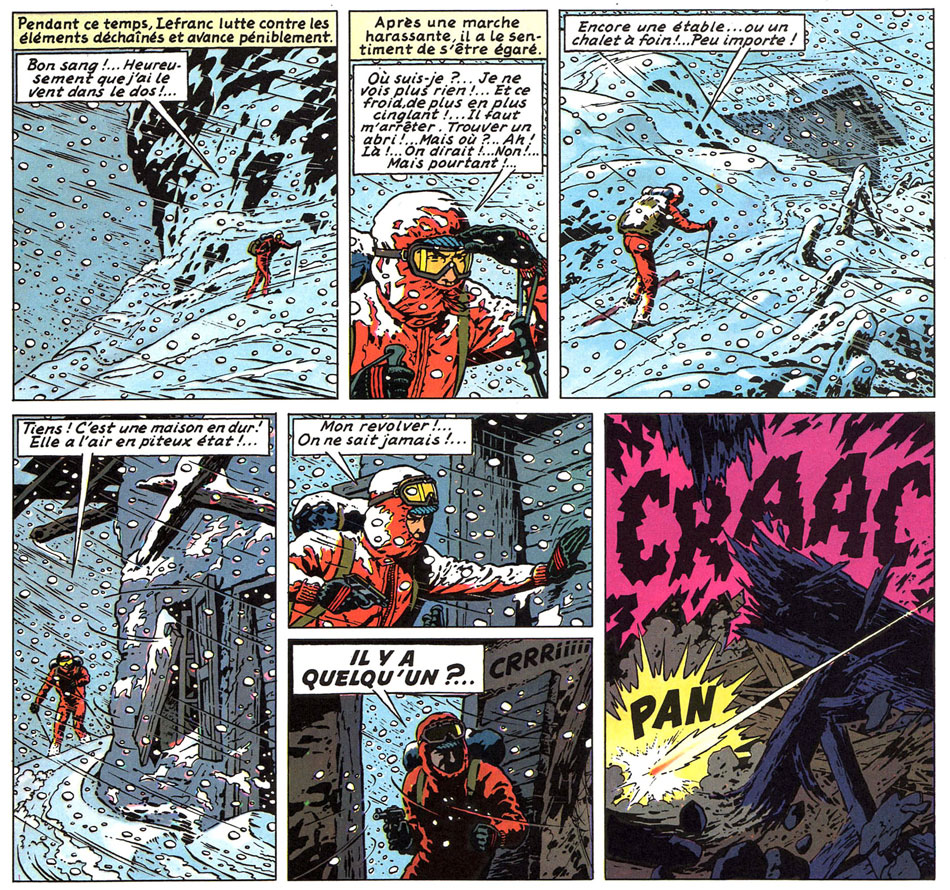

De Moor also proved a helping hand for other artists. His studio partner Jacques Martin was also working on solo projects, the historical adventures of the Gaul 'Alix' and the investigations of the journalist 'Lefranc'. In the past, De Moor had helped Martin with the backgrounds of some 'Alix' stories, but in 1970 he provided the full artwork for the 'Lefranc' episode 'Le Repaire du Loup', based on Martin's script. In addition, De Moor did some occasional scriptwriting work for others, for instance some gags for comics by Géri and and a story by Ploeg which appeared in Tintin Sélection #19 (1973).

Lefranc #4 - Le Repaire du Loup' (1970).

Post-Hergé period

By the 1980s, De Moor had been promoted to art director of the Studio's Hergé. After Hergé's death in 1983, the future was unsure. Hergé had stated that no new 'Tintin' stories should be created after his death. However, there was still the unfinished story 'Tintin and the Alpha Art' that Hergé had been working on, with close participation of De Moor. From the start, Bob De Moor expressed both doubt and eagerness to finish this final project. As it was still in its concept and sketch phase, the question arose whether this would be deemed a new story. At first, Hergé's wife and sole heir Fanny Rémi showed interest to have Bob De Moor work on it, but eventually came back on her decision. In 1986, 'Tintin et L'Alph-Art' received its book release, but as a collection of the sketches and script pages Hergé left behind. A description of the images and dialogue was added by experts like Hergé biographer Benoît Peeters, so readers could follow Hergé's line of thought.

Since the Studio's Hergé was not involved in this product, the whole experience had left De Moor deeply hurt. Since the death of Hergé, a rift had occurred between his widow and his personal secretary Alain Baran on one side, and the Studio's Hergé on the other. More and more, Bob De Moor felt sidetracked, since he assumed that Hergé saw him as his successor. During the final years of Studio's Hergé, De Moor worked on the designs for a 'Tintin' ride in the Walibi amusement park and two 'Tintin' murals for the Stokkel/Stoccle subway station in Sint-Pieters-Woluwe/Woluwe-Saint-Pierre (inaugurated on 31 August 1988), while his son Johan was working on an animated series and new comic stories with Hergé's 'Quick et Flupke' characters. In late 1986, Bob De Moor's contract with the Studio's Hergé was terminated.

De Moor's work for Hergé has both been praised and contested. Critics disliked him for basically drawing every 'Tintin'-related product, including the albums, while Hergé didn't even lift a pencil for it. Many scenes in later 'Tintin' stories look and feel more like artwork by De Moor than Hergé. In reality, Hergé kept a close watch on the production. He still sketched out every story beforehand and had the final say over the content of each new album. De Moor recalled having a lot of fun with Hergé, thinking up gags for his characters and future stories. While it is true that De Moor drew the majority of the backgrounds and more technical aspects, Hergé insisted on drawing his main cast characters personally.

Fans of De Moor also feel spiteful because De Moor's personal graphic output diminished significantly during his Studio's Hergé era (1951-1986). While Hergé's post-war comics appeared only sporadically, he and his assistants were still endlessly preparing and revising upcoming stories, redrawing and editing older 'Tintin' albums and creating merchandising art. Sometimes months or years of preparation for a new 'Tintin' story eventually turned out to have been a waste of time, once Hergé scrapped the entire project and spent his attention on a new, different plotline. It all chewed up time that De Moor could have spent on his own series. As a result, new gags and stories by De Moor could only be worked on during his spare time. Also when he was given opportunities to take over other series, Hergé interfered. In 1962, for instance, Jen Trubert had drawn three new stories starring the classic 'Bécassine' character, but quit afterwards. De Moor was asked to continue the series and made a few test drawings, but Hergé wanted to keep him at his own studio and so he simply obeyed. In the eyes of many De Moor fans, the artist sacrificed the majority of his talent and career in service to Hergé.

'Een Afspraak in 2009' (1989).

Graphic contributions

For the Belgian Pavillion at the 1967 Expo of Montréal, Bob De Moor designed a large panel. In 1968, he created the poster for the exhibition 'Het Stripverhaal in België' in the Royal Library of Brussels, reusing a drawing which appeared earlier in Tintin #14 (1966). He subsequently illustrated the cover of 'Het Beeldverhaal in Vlaanderen en Elders' (Archief en Museum van het Vlaams Cultuurleven '1969).

In 1980, De Moor designed a sticker for Unicef and the same year he was one of several Belgian comic artists to make a graphic contribution to the book 'Er Waren Eens Belgen.../Il Était Une Fois... Les Belges' (1980), which illustrated historical anecdotes about Belgium with a gag comic or illustration on the opposite page. For a 1983 special issue of (Á Suivre) and its Dutch-language edition Wordt Vervolgd, titled 'Adieu Hergé', he drew a graphic tribute to commemorate Hergé's death and designed the invitation for the 10th International Comics Festival of Angoulême that same year.

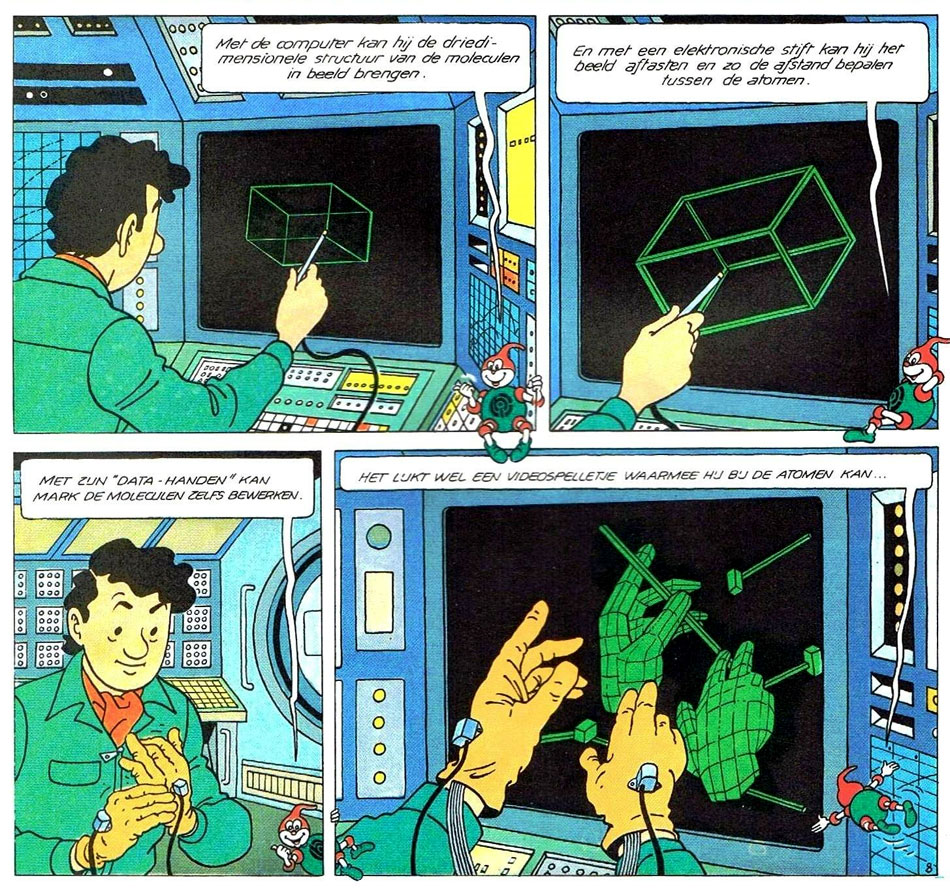

In 1987-1988, the publishing company Brain Factory International released a four-volume comic book series in which Franco-Belgian comic creators visualized songs by singer Jacques Brel in comic strip form. The second volume, 'Les Prénoms' (1987) featured a contribution by De Moor, illustrating the song 'Jojo'. In 1988, he parodied his own series 'Barelli' as 'Bary Lelli' in 'Les Auteurs Ravis Vous Proposent Leurs… Parodies' (Toulon, 1988), a collective comic book in which comic artists spoofed their own creations. He designed the cover of the debut album 'A World of Machines' (1982) by the Belgian pop band The Machines, best-known for the Belgian hits 'Don't Be Cruel' (1981) and '(I See) The Lies in Your Eyes ' (1982). On commission by the Federation of Chemical Industry, he made the educational comic book 'Een Afspraak in 2009' (1989).

Recognition

Having operated largely in the shadows, De Moor's talent was first honored in 1972, when he received the CISO-prijs for Special Achievements, awarded on 30 November 1972 in Breda. This recognition from Dutch/Flemish comic fans inspired him to pick up his own comic series again later that decade. Later, De Moor was awarded the 1985 "Stripclubprijs van de Vrienden van de 9e Kunst" and the 1988 Crayon d'Or (1988) from the Chambre Belge des Experts en Oeuvres d'Art for his entire body of work, while his 'Cori' story 'De Gedoemde Reis' won the Prix Jeunesse (1988) at the Comic Festival of Angoulême, France. In Québec, Canada, he was awarded in 1988 with the Prix Bédéis causa. In 1991, Bob De Moor was knighted by King Boudewijn/Baudouin as a Knight in the Order of Leopold.

'Balthazar' gag, printed in Kuifje issue #40 of 1966 (5 April), paying homage to "the glory of comics". The huge statue featuring a crowd of famous American, French, German and Belgian comic characters is shaped like Tintin's quiff. De Moor later reused the image for a 1966 exhibition in the Royal Library of Belgium in Brussels, which was the first exhibition on Belgian soil devoted to Belgian comics. In 1983, the image was also used for a comic festival and in 1989 in brochures by the Belgian Center of Comics in Brussels.

Comic promotion

From 1977, De Moor was a jury member of the Bronzen Adhemar awards and a member of the Vlaamse Onafhankelijke Stripgilde ("Flemish Independent Comics Guild"). On 24 October 1984, the Center of Belgian Comics was founded, an association to secure funds for a comics museum. Among its members were people like Alain Baran, Bob de Groot, Hec Leemans, François Schuiten and Marc Sleen. De Moor was named its president, because he was bilingual and respected on both sides of the language border. In 1989, when the Belgian Center of the Comic Strip opened its doors in Brussels, De Moor was honored as one of the Belgian comic pioneers in its permanent exhibition. The same year he was appointed artistic director of the publishing house Le Lombard. In 1990, De Moor was on the editorial board of JET, the first European magazine for young talent, published monthly by Le Lombard.

'Blake & Mortimer'. 'Les Trois Formules du Professeur Sato'. Dutch-language version.

Final years and death

With his work for Studio's Hergé terminated in 1986, De Moor made plans for other projects. Aided by his assistant Geert De Sutter, he began working on new stories of 'Cori de Scheepsjongen', the revival of 'Snoe en Snolleke' as 'Johan en Stefan', and on the continuation of Edgar P. Jacobs' classic 'Blake et Mortimer' series. In 1977, Jacobs had released the first volume of a new episode, 'Les Trois Formules du Professeur Satō' ('Professor Sató's Three Formulae'), but never finished the second volume. After the artist's death in 1987, Bob De Moor and his assistant created the second volume of the story, bearing the subtitle 'Mortimer vs Mortimer'. The book was published in 1990, to lukewarm reception.

In 1989 and 1992, De Moor suffered two strokes. During his hospitalisation he was diagnosed with lung cancer. He died in Brussels in the late summer of 1992. His final 'Cori' album was completed posthumously by his son Johan De Moor, aided by scriptwriter Stephen Desberg.

Bob De Moor signed his books in Kees Kousemaker's Lambiek store in Amsterdam on 21 February 1981.

Legacy and influence

De Moor is remembered by many as a jolly soul, who enjoyed his work and always had stories to tell. In an interview in Tintin issue #38 of 1975, he described comics as a "music-hall of paper" of which he enjoyed "the show, theater and spectacle". His comics and artwork are still admired by new generations of artists. Among the artists influenced by him are Philippe Geluck, Luc Morjaeu, Dirk Stallaert and Peter de Wit. De Moor's 'Barelli' comic was spoofed as a sex parody by Roger Brunel in 'Pastiches 3' (1984).

In September 1998, 'Cori' received his own comic book mural in the Rue des Fabriques/Fabrieksstraat in Brussels, as part of the Brussels Comic Book Route. The mural was designed by G. Oreopoulos and D. Vandegeerde. In 1989, the Waranda in Turnhout hosted an overview exposition of Bob De Moor's work, while an accompanying book was released. Since the 1970s, comic fan imprints like the Magnum series, the Collectie Fénix and BD Must have reprinted many of the early comics from Bob De Moor's Flemish career. In January 2019, the first issue of a new Flemish comic magazine, Stripkiosk, offered a reprint of his extremely rare comic book 'Bloske & Zwik, Detectives' as a free supplement.

Offspring

All of Bob De Moor's children have had careers in a creative profession, or have worked for media organizations. His oldest sons have been active in music, Chris De Moor (1949) as an opera singer and Dirk De Moor (1952) as a conductor and artistic director of the European Union Choirs. Like his father, Johan De Moor (1953) has become a comic artist and cartoonist, who first worked at Studio's Hergé and later gained fame with his own comic 'La Vache' (1992-2002) and as a Comic Art teacher at the Sint-Lukas School of Arts in Brussels. Bob De Moor's only daughter Annemie De Moor (1958) was a secretary at Studio's Hergé (1981-1986) and then worked for the publishing company Casterman (1987-2023). The youngest son Stefaan De Moor (1963) was in the 1990s working for the rights department of publisher Le Lombard, and later had a career in marketing and finances.

Books about Bob De Moor

In 1986, publisher Lombard celebrated the 40th anniversary of Bob De Moor's career with the book 'Bob de Moor - 40 jaar strips - 35 jaar aan de zijde van Hergé' (Lombard, 1986), compiled by Pierre-Yves Bourdil and Bernard Tordeur. For those interested in De Moor's life and career, Ronald Grossey's biography book 'Bob De Moor. De Klare Lijn en De Golven' (Vrijdag, 2013) is a must-read. The excellent website www.bobdemoor.info, hosted by Bernard Van Isacker and Luc Huygh, also keeps the latest news about De Moor in check.

Lambiek will always be grateful to Bob De Moor for illustrating the letter "M " in our encyclopedia book 'Wordt Vervolgd - Stripleksikon der Lage Landen', published in 1979.

Bob de Moor and his characters. Among the kids at the left side of the table (from left to right) are Snoe (Johan), Snolleke (Stefan) and two Lustige Kapoentjes. Behind the table, leaning over De Moor's shoulder one can spot aunt Sofie, Anna Nannah, Cori, Barelli, a knight from 'De Leeuw van Vlaanderen', Nonkel Zigomar, Meester Mus, Randor and Balthazar. The approving man in the painting is Hergé.