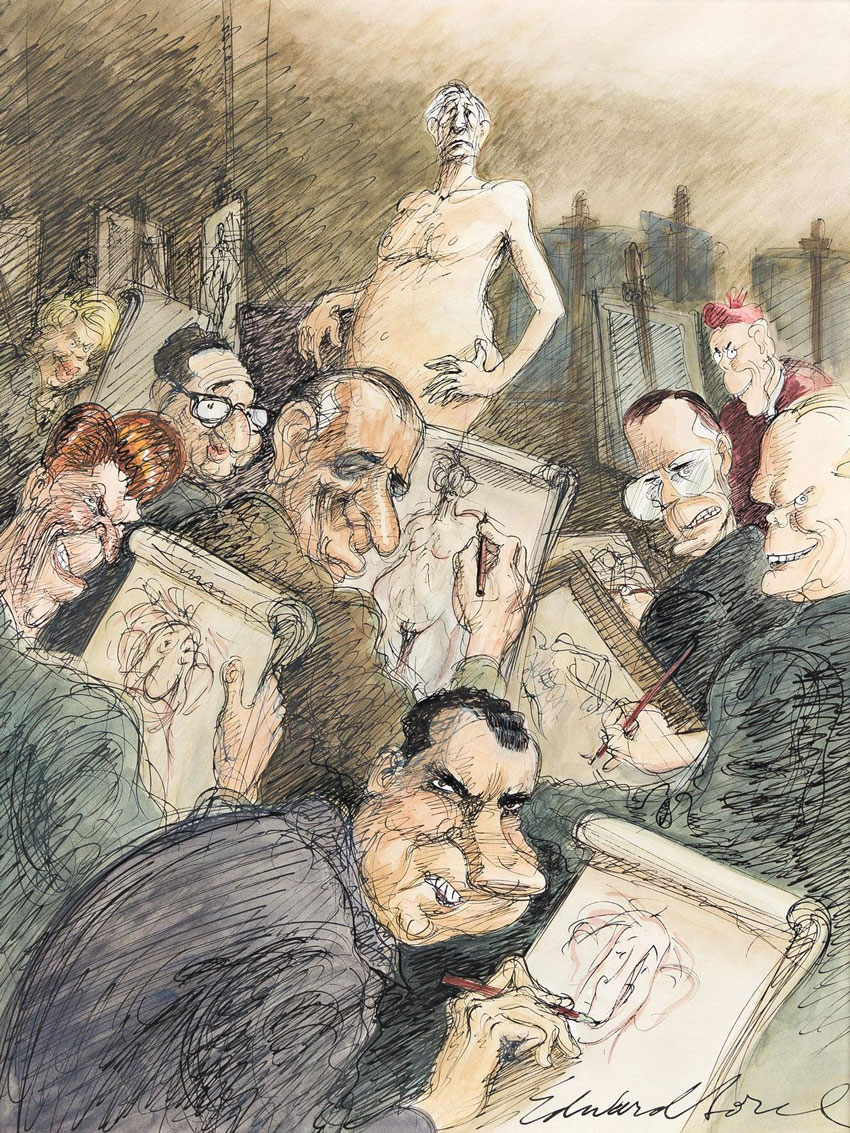

From: 'Superpen: The Cartoons and Caricatures of Edward Sorel' (1978).

Edward Sorel is an American magazine illustrator, caricaturist and comic artist. Working in a scribbly, spontaneous style, his favorite recurring topics were Hollywood stars, politics and organized religion. Apart from drawing satire, Sorel also drew biographical comics about literary giants under the banner 'Literary Lives', serialized in The Atlantic in the early 2000s. Late in his career, Sorel released the acclaimed graphic novel 'Mary Astor's Purple Diary: The Great American Sex Scandal of 1936' (Liveright Publishing, 2016), about the turbulent life and career of Hollywood actress Mary Astor. Sorel's caricatures have often received awards and have been the subjects of thematic expos.

Early life and career

Born as Edward Schwartz in 1929 in The Bronx, New York, Sorel was the son of a Romanian-Jewish door-to-door salesman in dry goods. His mother worked in a hat factory. As his father had a lot of spare time, he was often just lying around on his sofa. Sorel grew up with a hatred for him. He had fled from Poland to escape the draft and basically forced a woman to marry him, in order to be able to stay in the USA. Sorel often observed his father doing nothing all day, while his mother was the real breadwinner. Ironically enough, despite being an immigrant himself, his father had racist views and, when his son was old enough, he wanted him to enlist in the army. However, this plan never came to fruition, since the family was so poor. Sorel also didn't like the rest of his family, who were a group of devout religious conservatives on one hand and staunch communists on the other, making family meetings a cacophony of fierce arguments. Sorel became a lifelong atheist, with a distrust of authority, and found escapism in watching movies, reading comics and novels and drawing.

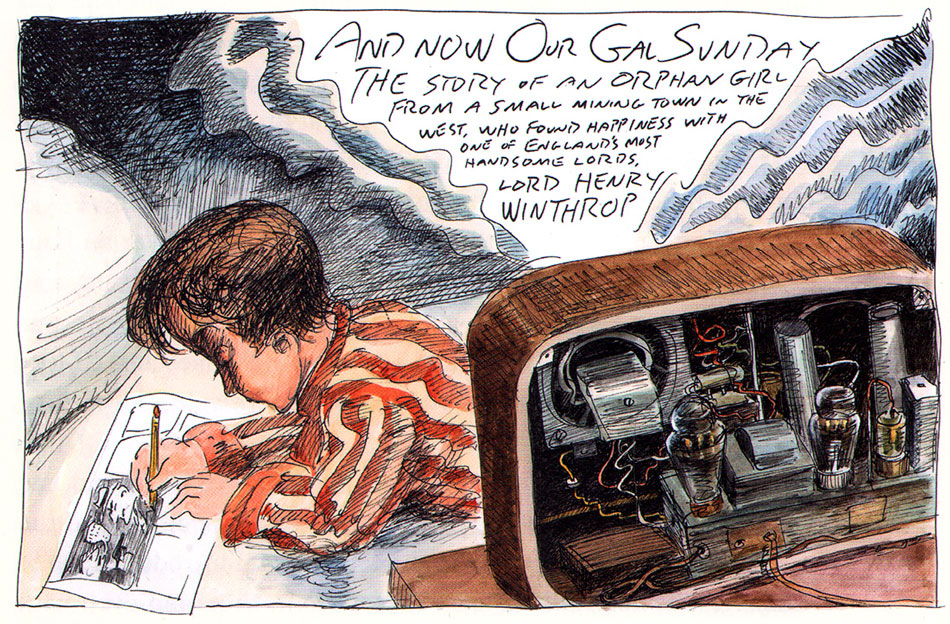

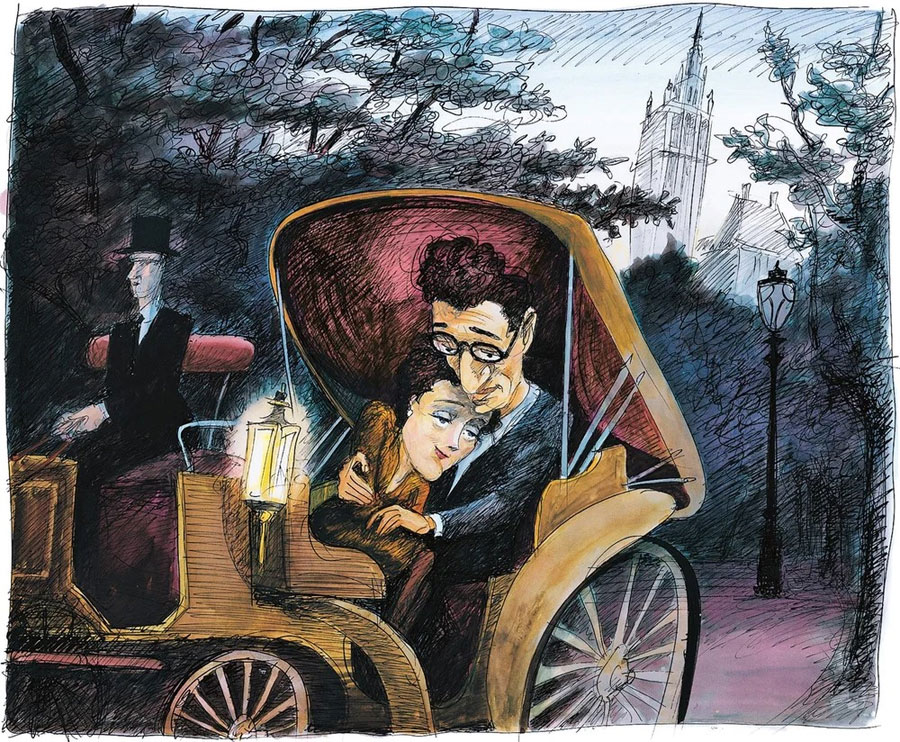

From: 'Profusely Illustrated: A Memoir' (2011).

At age 8-9, the boy spent almost a year in bed due to double pneumonia, which still back then was a serious illness. During these 12 months, he passed the time by learning to draw. Among his main graphic inspirations were German expressionism, the painters Rembrandt Van Rijn, David Hughes, Alice Neel and Robert Andrew Parker, as well as illustrators and cartoonists such as Ludwig Bemelmans, Honoré Daumier, Gustave Doré, André François, David Levine, Lee Lorenz, James McMullan, Pat Oliphant, Thomas Rowlandson, Ronald Searle, Ralph Steadman, William Steig, Arthur Szyk, Felix Topolski and Gluyas Williams. His favorite comic artists were Clare Briggs, Robert Crumb, Billy DeBeck, Jules Feiffer, Ben Katchor, George McManus, E.C. Segar and Cliff Sterrett.

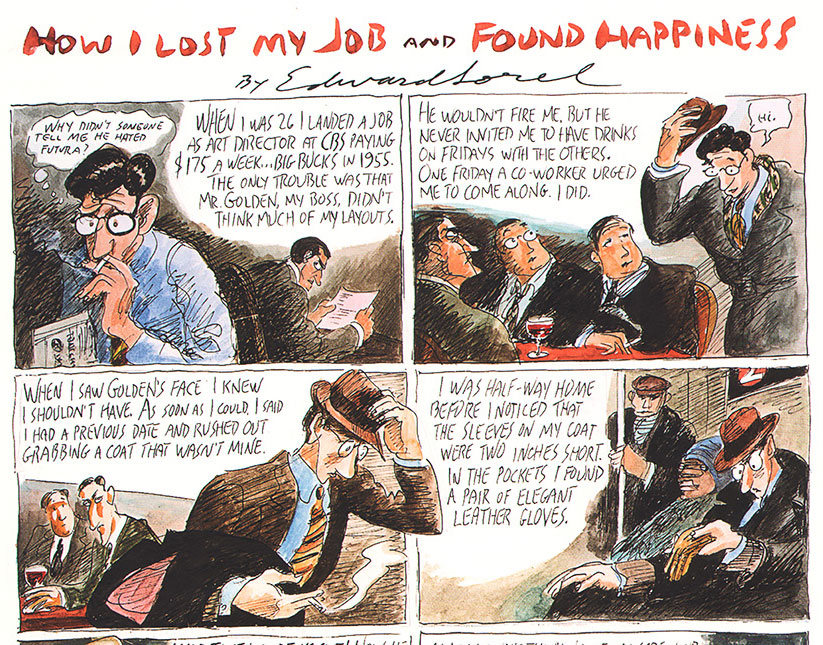

Edward Sorel went to the High School of Music & Art, but regarded it as a waste of time, since the teachers focused more on theory than on actual drawing. He followed it up with studies at The Cooper Union for Advancement of Science and Art in Manhattan, where he befriended future talents Seymour Chwast and Milton Glaser. Interviewed by R.O. Blechman for The Comics Journal (25 October 2012), Sorel remembered that he was "in the clique with the losers", while Glaser and Chwast were among the talented artists. After graduating in 1951, Sorel managed to get hired and fired by no less than eleven companies, which he claimed must have been "a record". Every time he applied for a different company, he snuck some graphic designs by more skilled colleagues in his portfolio, which helped him get hired with a much higher salary than before, but once his editors noticed he wasn't the virtuoso he claimed, he was just as quickly shown the door again. Interviewed by Gary Groth for The Comics Journal issue #158 (April 1993), Sorel recalled that "by the middle of 1951, I was lasting on jobs only about three days before they realized I was unsuited for it." Eventually, in 1953 he managed to get a longer-lasting job at Esquire magazine, where he was later joined by Chwast. Being able to rely on his friend's advice and help, caused Sorel's artwork to improve. But after working for 11 months for this publication, the editors decided to fire half of the art staff.

'How I Lost My Job And Found Happiness' (The Nation, 24 January 2008).

Sorel and Chwast put their money together to share a cheap flat with cold water, which they turned into their own Push Pin Studios, where they were joined by Milton Glaser and Reynold Ruffins. While they received a lot of commissions and were able to move into a more luxurious building after two years, in 1956, Sorel decided to go solo. He often clashed with his friends, who were in favor of abstract art and considered his illustrations "old-fashioned." Sorel dismissed it: "Abstraction and modern art is what people who can't draw love." But even he couldn't deny that he was the weakest link in the studio, so he often took care of the sales instead of drawing. After Sorel's departure, Push Pin kept flourishing and gave many other talents a chance throughout the decades.

Style

In 1956, Edward Schwartz went freelance and chose the name "Sorel" as his pseudonym, derived from the protagonist Julien Sorel in the classic novel 'Le Rouge et Le Noir' ("The Red and the Black") by the 19th-century French novelist Stendhal. Interviewed by Henry Chamberlain for Comics Grinder (8 February 2017), Sorel explained: "(...) I saw myself in Julian Sorel because he was like catnip to women, which I really wasn't, and he hated the corrupt society of his time, as I hated mine. (...) The other thing about Julian Sorel was that he hated his father. God, I certainly hated mine, not only because he tried to discourage me in wanting to be an artist but because he was a mean-spirited ignorant man not kind to my mother, not kind to anyone. And I didn't want anything to do with him. I was going to be a cartoonist and I didn't want to sign my name, Schwartz, in the right-hand corner. (...) I chose the name, Sorel, because of the novel. It seemed as good a name as any." In the early 1960s, Sorel moved to upstate New York, where his close neighbor was watercolor painter Robert Andrew Parker, whose style influenced him strongly.

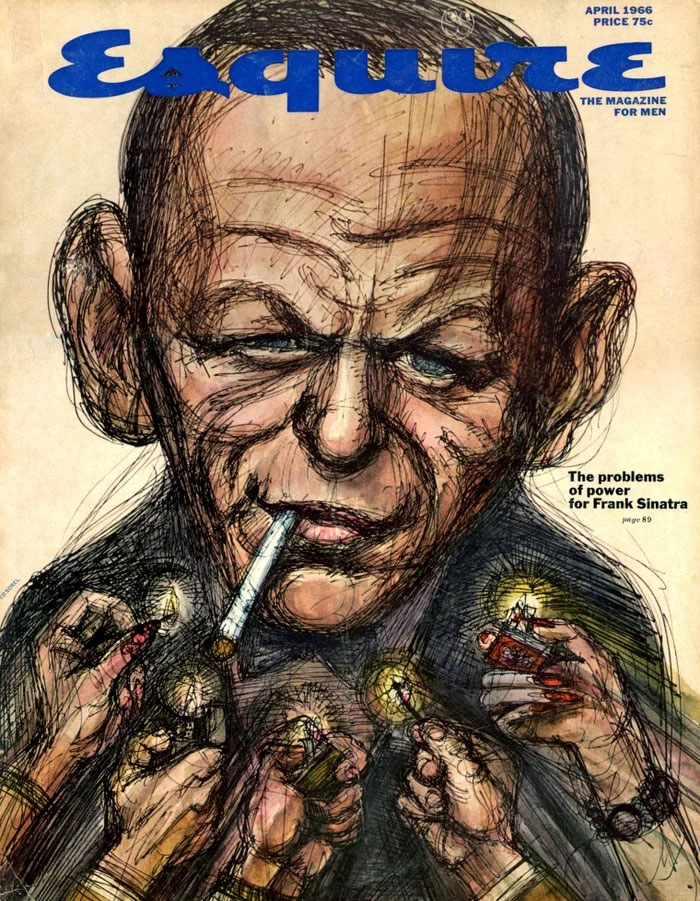

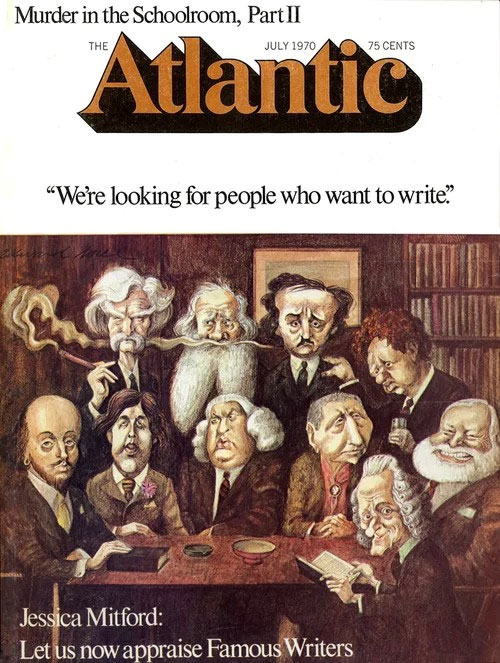

Cover drawings with caricature of Frank Sinatra for Esquire (April 1966) and of writers Mark Twain, Leo Tolstoy, Edgar Allan Poe, an unidentified writer, William Shakespeare, Oscar Wilde, Samuel Boswell, another unidentified writer, Voltaire and Ernest Hemingway, for The Atlantic (July 1970).

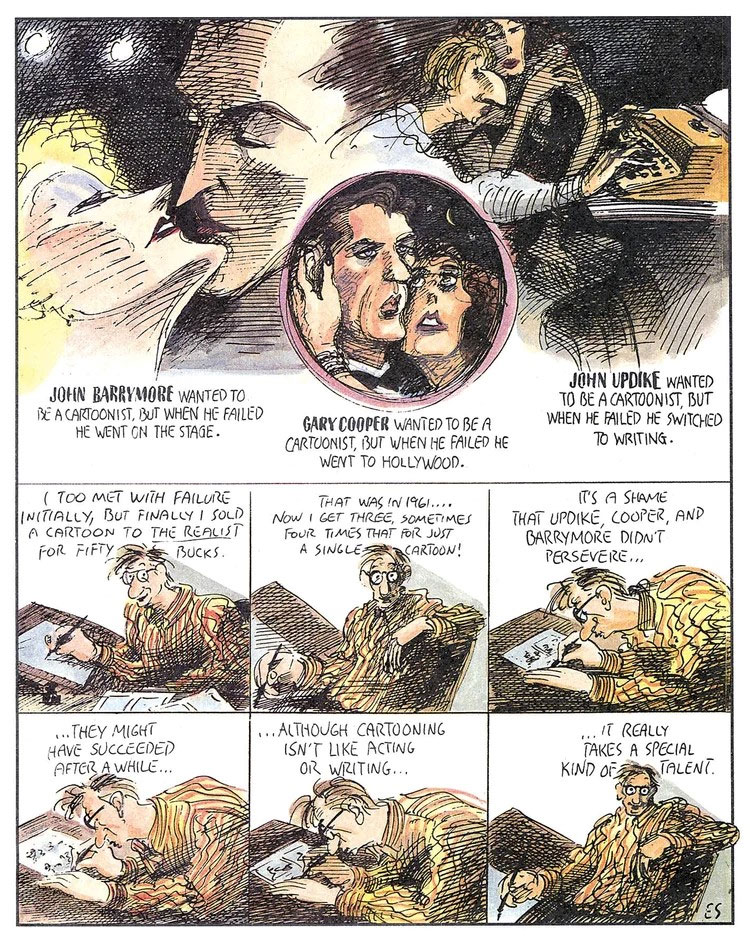

In the previously mentioned 1993 Comics Journal interview, Sorel referred to himself as the "patron saint of late starters". In his opinion, he only made his first "good" drawing when he was already 40, finally figuring out how to draw vividly and visualize a good gag. Sorel's earliest cartoons ran in the satirical magazine The Realist (1961), after which he became art director for another satirical publication, Monocle. He became particularly associated with the men's magazine Esquire, designing covers and livening up articles for many decades. Sorel illustrated one of their most famous articles, Gay Talese's 'Frank Sinatra Has A Cold' (April 1966), which was groundbreaking for discussing a topic in an unusual, personal, but colorful manner. Simultaneously, Sorel also found his own voice. As he was preparing his portrait of Sinatra for the cover, he faced a deadline and therefore made a very quick, spontaneous drawing that nevertheless perfectly captured the singer's face with scribbly lines that were full of movement. Like so many artists, Sorel always felt his sketches had more vitality than the finished artwork, which looked "dead and overworked" in comparison. By keeping the spontaneity and directness of his sketches intact and avoiding tracing, he established his trademark sketchy style. In the Comics Grinder interview, he said: "Tracing (...) that's impossible to do if you're doing very complicated scenes. You can work directly if you're doing a face, a figure, a still life, or anything relatively simple. You can work directly without tracing and the work has a vitality to it. But when you're doing complicated scenes, with many different elements, you really do have to know where you're going. So, I found out that if I just had a light outline of where I wanted the elements to be, and didn't trace, I could keep this sketchy quality that I think gave my art work some distinction."

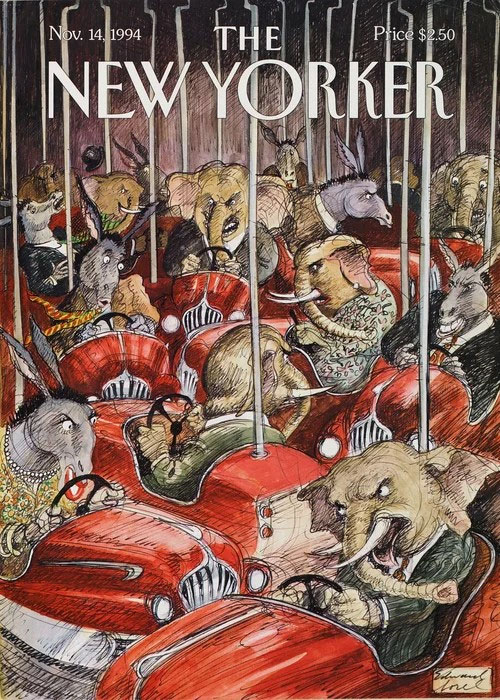

Covers for The New Yorker (14 November 1994 and 18 January 1999).

Interviewed by Sage Stossel (The Atlantic Unbound, 6 November 1997), Sorel stressed out the importance of spontaneity: "Anything that's labored ceases to be funny. It only works if it looks easy. A good example is Fred Astaire's dancing. I think the reason that we enjoy it so, is because it looks so effortless. The fact that it took hours and hours of painful rehearsal is immaterial as long as the finished product looks effortless. It's the same with my drawing. I do many, many preliminary sketches, but as long as the finished product looks like it was easy to do, it's successful." He also regarded himself as a humorist first and foremost, since he didn't consider himself very talented in conveying serious topics.

Cartooning and caricaturing career

From the 1950s until into the 2020s, Sorel was a regular appearance in many magazines, most notably American Heritage, American Horizon, The Atlantic, Esquire, Forbes, Fortune, Harper's Magazine, National Lampoon, Penthouse, Ramparts, Rolling Stone, Time and The Village Voice. He was most recognizable as a caricaturist. In the 1960s and 1970s, he drew monthly portraits of politicians, depicted as animals with human heads, printed in Ramparts. Around 1970, he had his own syndicated caricature column, 'Sorel's News Service', distributed by King Features, which lasted a year. Between 1974 and 1978, Sorel drew weekly topical comics for The Village Voice. For Esquire, he often illustrated the column 'Movie Classics', giving a graphic interpretation of a movie scene, with trivia about the making of this picture printed next to his drawing. A huge fan of movies from the Golden Age of Hollywood, Sorel enjoyed caricaturing Hollywood actors, but still disbanded 'Movie Classics' after a year, since he felt it started to look as if he merely traced movie stills with no additional value.

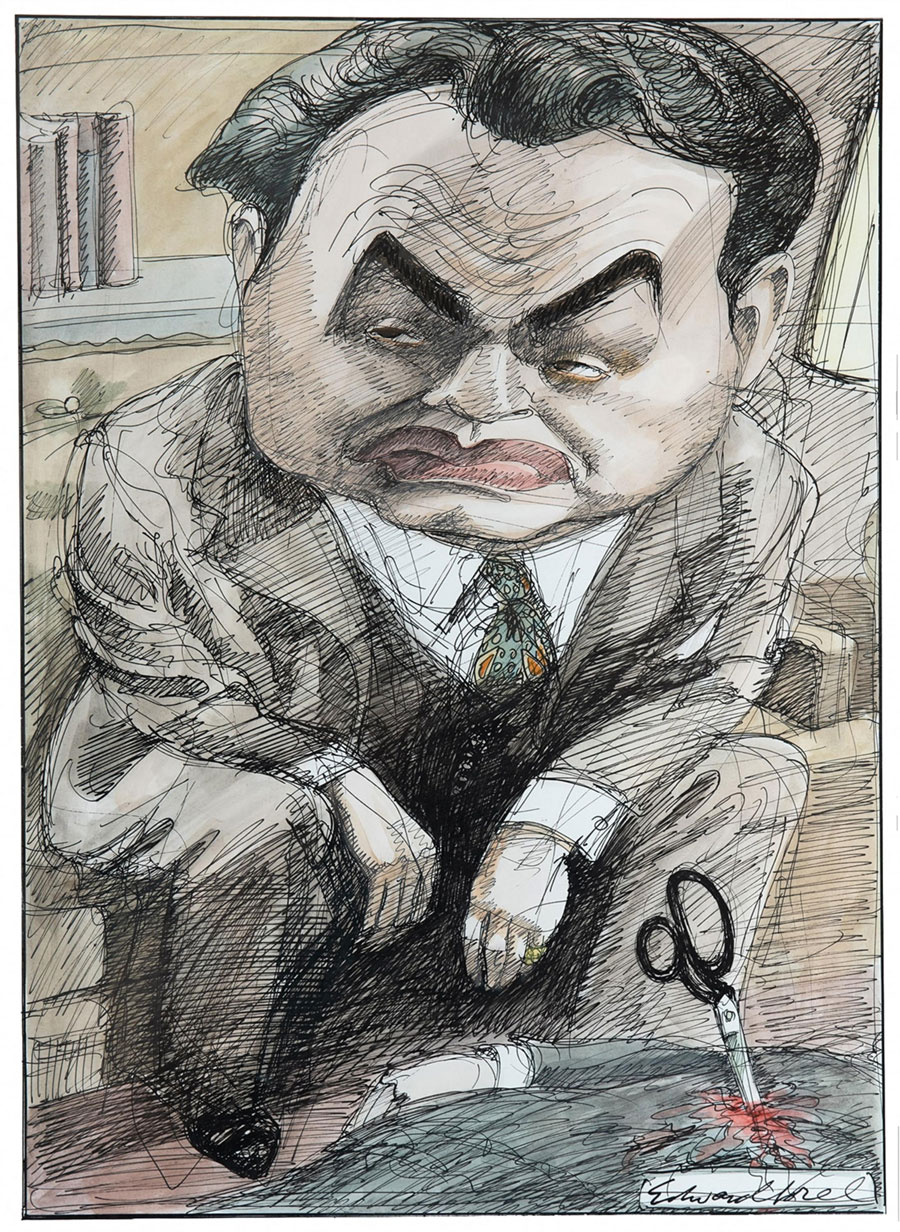

Edward Sorel's drawing of Edward G. Robinson.

Sorel nevertheless kept caricaturing Hollywood stars for other magazines. He admitted having more awe for the actors he grew up with in the 1930s and 1940s, who seemed "larger than life", than those from later generations. His personal favorite was a portrait he made of Edward G. Robinson for The New Yorker, based on a scene from 'The Woman in the Window' (1944). He felt it turned out exceptionally well and he also received many requests from readers afterwards who wanted to buy the original. Interviewed by Randy Cohen for PersonPlaceThing (12 March 2022), Sorel said that "if I was a pharaoh, I would want that caricature to be buried with me."

Comic strip featuring Sorel reflecting on his career, Penthouse, 12 December 1988.

Sorel also made general parodies of paintings, film posters and other graphic art for various magazines. From 1982 on, Sorel and his wife Nancy started the series 'First Encounters' for The Atlantic (1982-1996), depicting fantasized meetings between two famous people, for which Nancy Caldwell Sorel wrote the accompanying stories. They were collected in the book 'First Encounters' (Alfred A. Knopf, 1994). Sorel also designed advertisements for various companies, fully admitting that he needed the income to enable him to draw the projects he really wanted to do.

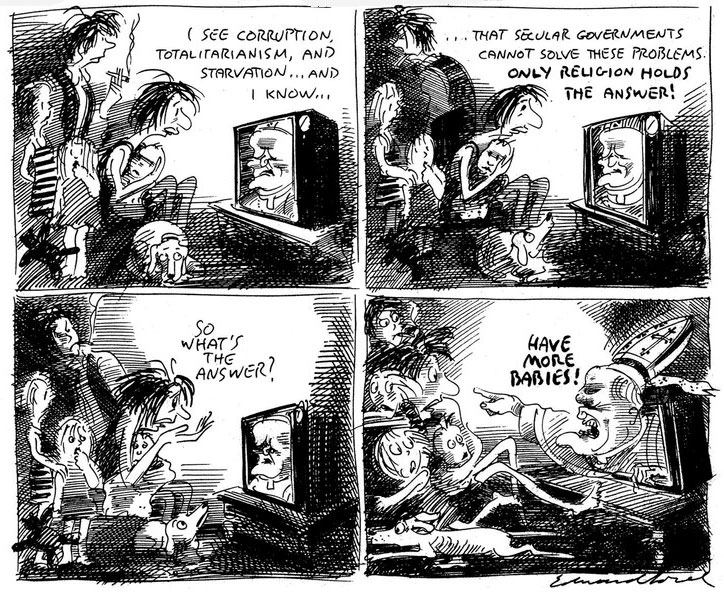

Part of a comic strip for The Nation, depicting Pope John Paul II.

Political cartoons and comic strips

Sorel started to rise as a political caricaturist after publishing the satirical books 'How to Be President: Some Hard and Fast Rules' (Grove Press, 1960) and 'Moon Missing' (Simon & Schuster, 1962). Several of his political caricatures ran in American Horizon, Penthouse, Ramparts, Rolling Stone, The Village Voice and his own syndicated newspaper column, 'Sorel's News Service'. They criticized the Vietnam War, several scandals and targeted politicians all over the ideological spectrum. Sorel held the opinion that all US Presidents from Dwight D. Eisenhower to Donald Trump had been atrocious for a variety of reasons. In 2016, after caricaturing Trump for Vanity Fair as the Greek mythological character Medusa, Sorel reflected that previous US presidents were hypocrites that you could have fun with, but considered Trump so unhinged, dangerous and cruel that making fun of him only trivializes him.

One time in American Horizon, Sorel had drawn politician Barry Goldwater as a knight sitting backwards on his horse and was stunned when Goldwater actually wanted to buy the original. Sorel refused, while the editors informed him that the politician was head of the postal committee in the Senate and he could decide whether magazines could receive a special postal rate, or not. If he raised theirs, they would be out of business. Sorel snapped back: "Well, I guess you're out of business, then, because I'm not giving my original." Luckily the editors came up with an excuse to Goldwater and the postal rates were kept the way they were.

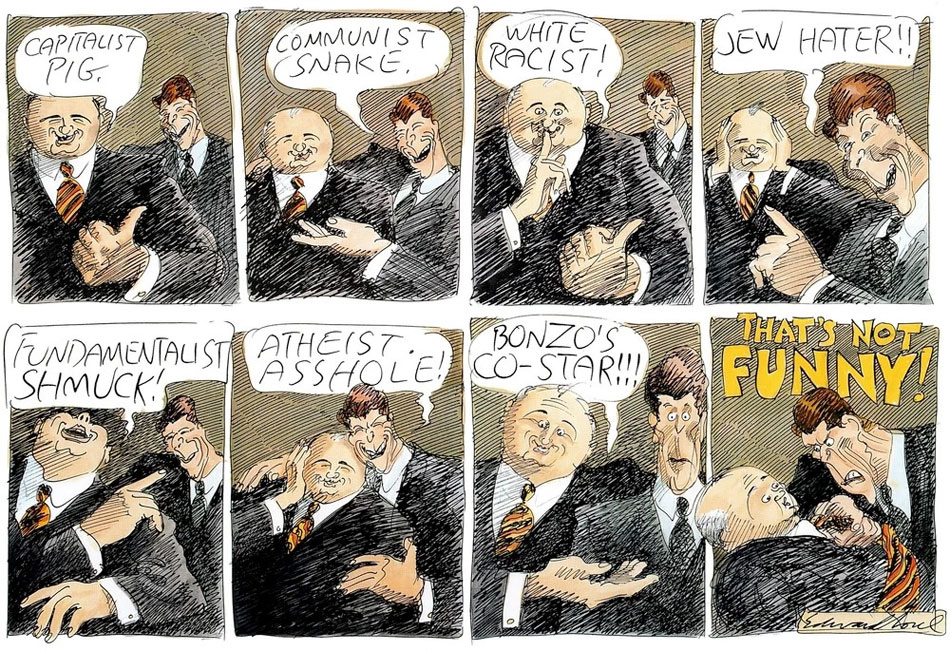

Gag comic by Edward Sorel, depicting U.S. President Ronald Reagan and Russian head of state Mikhail Gorbachev. 'Bedtime for Bonzo' was a 1951 B-movie in which Reagan acted alongside a chimpanzee named Bonzo (the real-life Reagan wasn't embarrassed by this movie, by the way.)

By 1988, Sorel was house cartoonist of the left-wing magazine The Nation, for which he drew a weekly comic strip featuring political and religious satire. Both The Nation and Penthouse were his favorite magazines to work for, since they gave him creative freedom, even though The Nation paid badly and Penthouse's pornographic content was sometimes a bit much to him. The Nation was also one of the few US magazines to allow satire of organized religion, a topic dear to Sorel's heart. While party politics tend to change more, the Church's institutional ideology remains quite consistent, allowing for more timeless satire. Sorel left Penthouse for a period of five years, since his daughter was teased about it in college by students who found out her father worked for a "nudie magazine". After her graduation, he returned to the title. In 1992, Sorel became a frequent contributor to The New Yorker. His first cover was a striking image of a punk being driven around in Central Park in a horse carriage. Over the decades, he made more than 40 cover illustrations, increasing his global fame.

One of the few commissions Sorel ever rejected was a magazine cover supporting a point-of-view that the press treated former and disgraced US President Richard Nixon unfairly: "I said that's too much. I'll sell out, but there are limits." In the field of advertising, he also rejected an offer from Philip Morris to make illustrations for them, despite the fact that he was a smoker himself.

Sorel's cartoons have been collected in the books 'Sorel's World's Fair' (McGraw-Hill, 1964), 'Making the World Safe for Hypocrisy' (Swallow Press, 1972), 'Superpen: The Cartoons and Caricatures of Edward Sorel' (Random House, 1978), 'Unauthorized Portraits' (Alfred A. Knopf, 1997), 'Literary Lives' (Bloomsbury, 2006) and 'Just When You Thought Things Couldn't Get Worse: The Cartoons and Comic Strips of Edward Sorel' (W.W. Norton, 2007).

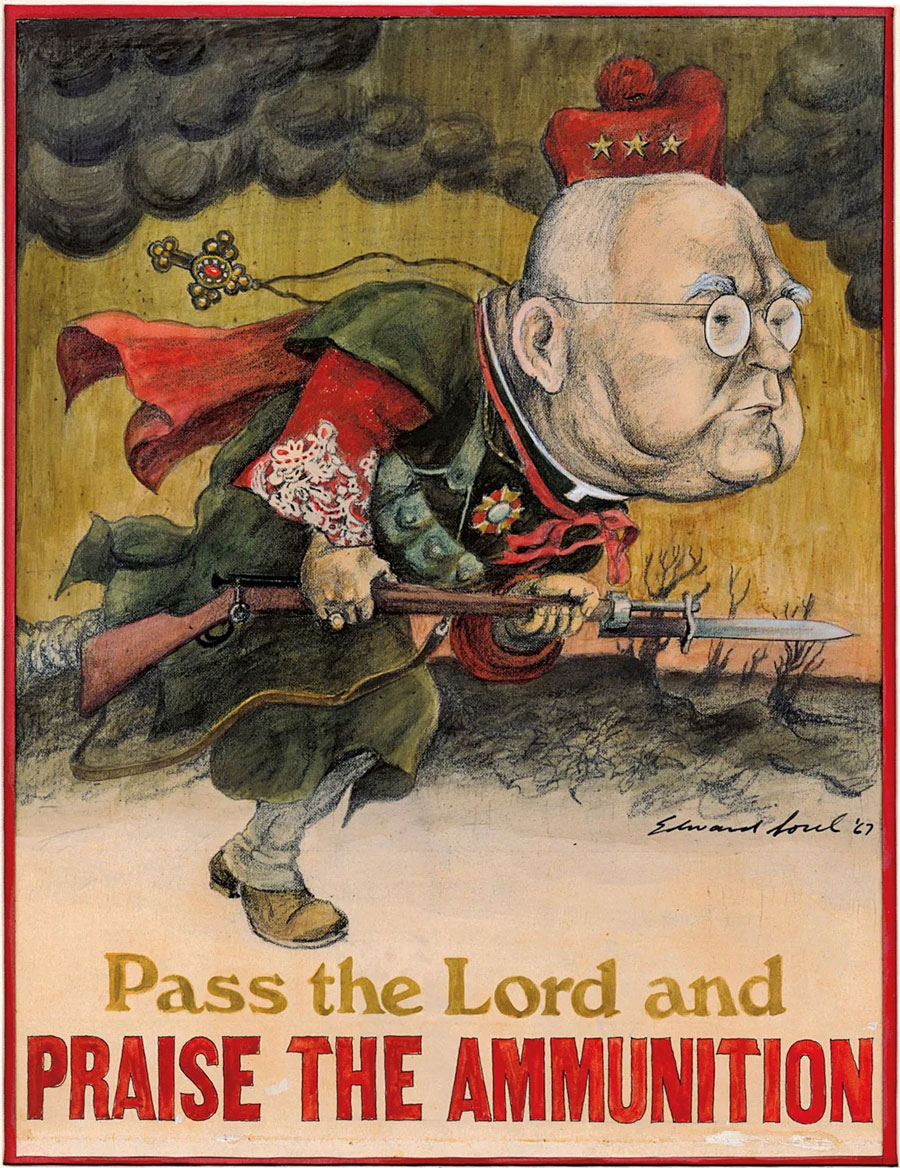

"Pass the Lord and Praise the Ammunition" poster (1967), depicting cardinal and archbishop of New York Francis Spellman.

Controversy

Edward Sorel made several posters for the anti-war movement against the Vietnam War and to rally people to join in during demonstrations. In 1967, he made a poster depicting the controversial archbishop of New York, Francis Spellman, who supported the US military intervention in Vietnam and advocated it as a "holy war between Christians and godless Communists." Sorel depicted the religious fundamentalist charging with a bayonet, while spoofing the song title 'Praise the Lord and Pass the Ammunition' as "Pass the Lord and Praise the Ammunition". As bad luck would have it, Spellman died on the day the poster came off the press. Now completely dated, it could no longer be sold. One store in Chicago tried, but vandals smashed the shop window. In 1972, Sorel also used the image as the cover for his book 'Making the World Safe for Hypocrisy'.

When Sorel made topical comics under the title 'Sorel's News Service', he drew a cartoon of US President Richard Nixon juggling skulls, accompanied by a real-life quote by him: "Fun is being president so you can do all the things you couldn't do if you weren't president." Made at the height of the Vietnam War, many readers felt offended, ending Sorel's comic strip after only a year.

'Sorel's News Service' (13 March 1970), with a caricature of Ronald Reagan.

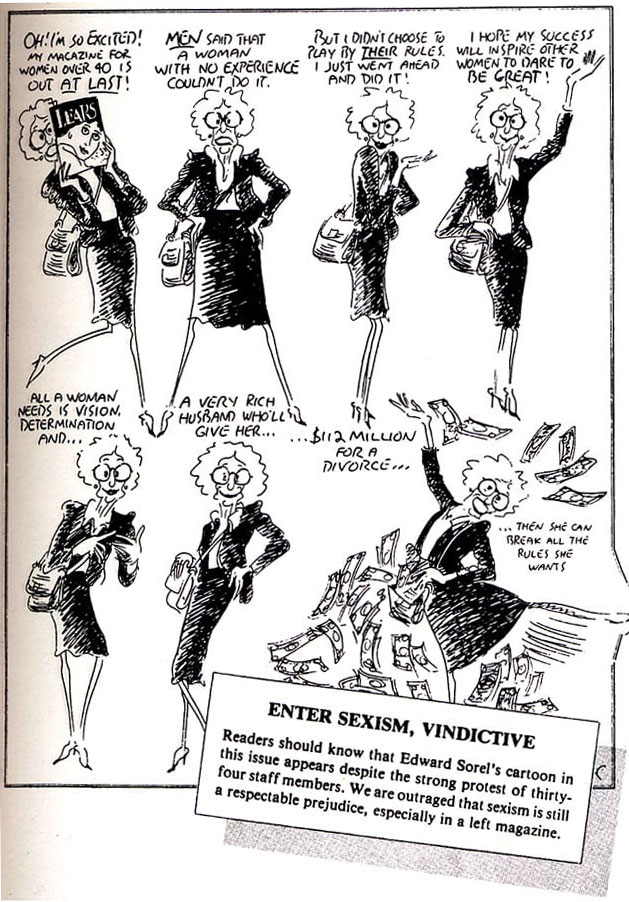

In 1985, the feminist activist Frances Loeb, better known as Frances Lear, divorced her husband, Norman Lear, most famous as the scriptwriter of the taboo-breaking satirical sitcom 'All In The Family'. She used money from her million-dollar divorce settlement to establish a women's magazine, Lear's (1988), aimed at women over 40, telling them it is never too late to start a new life to fulfill themselves. In the next issue of The Nation, Sorel satirized her, expressing the same message, but with the stinger punchline: "All a woman needs is vision, determination and a very rich husband who'll give her... 112 million dollars for a divorce... then she can break all the rules she wants." The Nation's staff, however, felt the need to add an editor's note, distancing themselves from the cartoon, which they perceived as "sexist". The controversy quickly snowballed into a national press story, but Sorel had no regrets.

Edward Sorel's comic strip on Frances Lear, for The Nation (1988).

Literary Lives

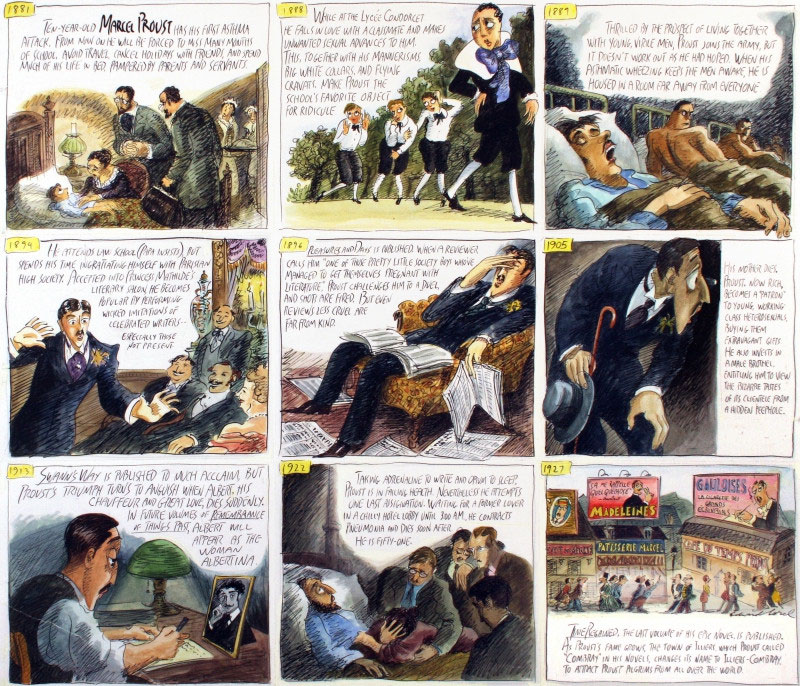

In the 2000s, Sorel drew 'Literary Lives', short biographies in comic strip form about writers Leo Tolstoy, Marcel Proust, Ayn Rand, Lilian Hellman, Carl Gustav Jung, Jean-Paul Sartre, W.B. Yeats, George Eliot, Bertolt Brecht and Norman Mailer, serialized in The Atlantic Monthly. These were later bundled in the book 'Literary Lives' (Bloomsbury, 2006), except for the very first biopic he drew, about Honoré de Balzac, since his life story wasn't so colorful compared with the other writers.

'Literary Lives: Marcel Proust'.

Mary Astor's Purple Diary

One day in 1965, Edward Sorel was tearing up old linoleum in his apartment and suddenly found newspapers from the 1930s underneath. As he started reading them, he noticed several headlines about a nowadays long-forgotten scandal from 1936 regarding an affair between playwright George S. Kaufman and Hollywood actress Mary Astor. At the time, Astor was married and Kaufman was involved in a child custody suit with his own ex-wife. Astor's husband threatened to publish one of Astor's diaries and reveal the affair, but this never happened. Instead, supposed details from the affair did reach the gossip columns and were repeated in the popular press, even though much was sensationalized.

'Mary Astor's Purple Diary: The Great American Sex Scandal of 1936' (2016).

Sorel was intrigued by this scandal and kept reading more about Mary Astor in the following decades. He discovered that the actress suffered from a dominant father who, even in her adulthood kept trying to limit her liberty. This all had an effect on her personality and Sorel observed that she made many terrible mistakes in her life, particularly in her love life, picking out partners that were just as controlling and violent as her father. This all culminated in Sorel's self-written and illustrated book: 'Mary Astor's Purple Diary: The Great American Sex Scandal of 1936' (Liveright Publishing, 2016). The reason he made it so late in his career was because he finally had more free time when magazine and advertising art commissions started to dry up and felt the time was finally ripe. The original draft was a straightforward retelling of Astor's lifestory, but one of the assistant editors of his publisher advised him to put himself in the narrative too. Once Sorel added this autobiographical element, the story became more fun to make. Creatively satisfying, he felt the book was even the highlight of his entire artistic career. One of the people who gave it an enthusiastic review was Woody Allen, who named it a "terrific book (...) with (...) wonderful caricature drawings. Who would figure that Mary Astor's life would provide such entertaining reading, but in Sorel's colloquial, eccentric style, the tale he tells is juicy, funny, and in the end, touching."

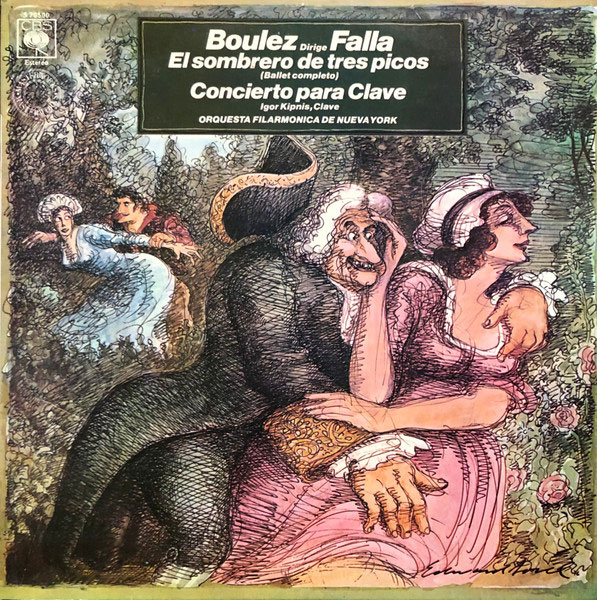

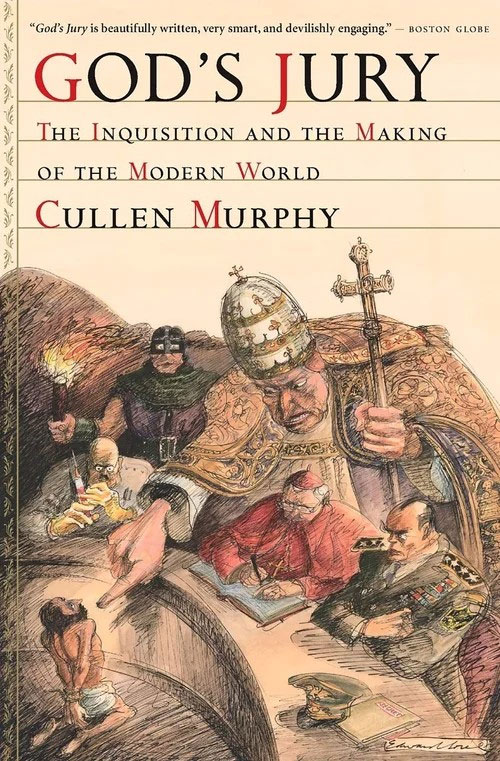

Cover art by Edward Sorel for a classical music album devoted to the music of Manuel de Falla and Cullen Murphy's non-fiction book 'God's Jury'.

Illustration work

Over the years, Edward Sorel designed album covers for various classical music and jazz albums, issued by Columbia, Harmony, Nonesuch, RCA Victor and Turnabout. Among his more notable covers were the soundtrack album of the Academy Award-winning musical film 'Gigi' (1958), a record based on the children's TV show 'Captain Kangaroo' ('Captain Kangaroo's TV Party', 1961) and David Frye's comedy album 'I Am the President' (1969). Sorel also livened up the sleeve of a disco record, 'Hotel Paradise' (1979), by Diva Gray and Oyster.

In addition, Sorel drew the cover of Cullen Murphy's book 'God's Jury: The Inquisition and Making of the Modern World' (Mariner Books, 2010) and illustrated Steve Brodner's 'Living & Dying in America', a daily column in The Nation about the 2020-2022 COVID-19 pandemic, focusing on the victims, but also the politicians, pundits and private entrepreneurs trying to capitalize on the drama for personal gain. The columns were collected in book format as 'Living & Dying in America: A Daily Chronicle' (Fantagraphics, 2022).

Sorel illustrated various children's books, mostly by Warren Miller: 'King Carlo of Capri' (1958), 'Pablo Paints a Picture' (1959) and 'The Goings-On At Little Wishful' (1959). For Nancy Sherman, he illustrated 'Gwendolyn the Miracle Hen' (1961) and the follow-up, 'Gwendolyn and the Weathercock' (1963). Sorel additionally livened up William Cole's 'What's Good For A Five-Year Old' (1969), Joy Cowley's 'The Duck in the Gun' (1969), Jay Williams' 'Magical Storybook' (1972) and Adam Begley's 'Certitude: A Profusely Illustrated Guide to Blockheads and Bullheads, Past and Present' (2009). The artist also helped out with retellings of old stories, like Ward Botsford's 'The Pirates of Penzance' (1981) and Craig Hill's translation of Jean de la Fontaine's Fables (2008). A special case is his contribution to Rabbit Ears Productions' children's TV series 'We All Have Tales' (1991-1995). In each episode, a fairy tale from somewhere in the world was visualized by having picture book drawings move as still images through each scene, zooming in and zooming out. Sorel illustrated 'Jack and the Beanstalk' (1991), accompanied by atmospheric music by David A. Stewart and narration by Michael Palin. Sorel's adaptation was also made available as audiobook through Listening Library. Sorel also wrote, or co-wrote, three children's books of his own: 'The Zillionaire's Daughter' (Warner Juvenile Books, 1989), 'Johnny-On-The-Spot' (M.K. McElderry Books, 1998) and 'The Saturday Kid' (with Cheryl Carlesimo, M.K. McElderry Books, 2000 ). Together with his wife Nancy Caldwell as writer, Sorel made the books'Word People' (1970) and 'First Encounters' (1998).

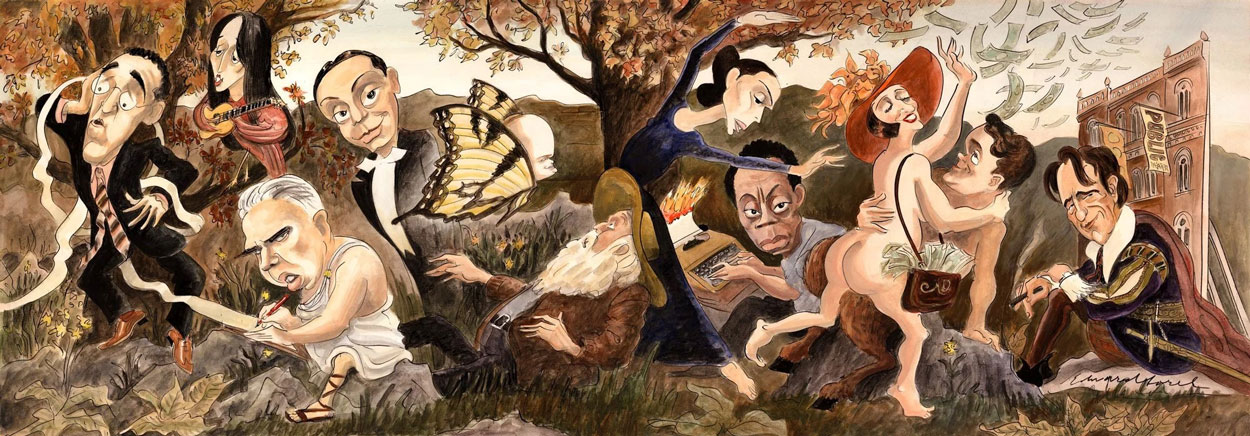

A section of Edward Sorel's Waverly Inn mural (2007). From left to right: columnist S.J. Perelman, folk singer Joan Baez, novelist Theodore Dreiser, composer Cole Porter, novelist Truman Capote, poet Walt Whitman, dancer Martha Graham, writer and activist James Baldwin, socialite Mabel Dodge, journalist John Reed and theatre producer Joe Papp.

In 2007, Sorel designed a mural for The Waverly Inn in Greenwich Village, New York, depicting many celebrities who once lived or worked in Greenwich, including Truman Capote, Joan Baez, James Baldwin, Bob Dylan, Walt Whitman and Andy Warhol. A book about the mural and his preliminary sketches was published afterwards, 'The Mural at the Waverly Inn' (Pantheon Books, 2008). On 25 June 2012, a fire broke out in the basement of the Waverly Inn. While the fire was extinguished without any victims, the firefighters were forced to break through the mural to get inside, damaging the artwork. However, Sorel said that the mural was merely a reproduction of his original drawing that can easily be reproduced from digital files. Sorel also designed a mural for the Monkey Bar Restaurant in the same city.

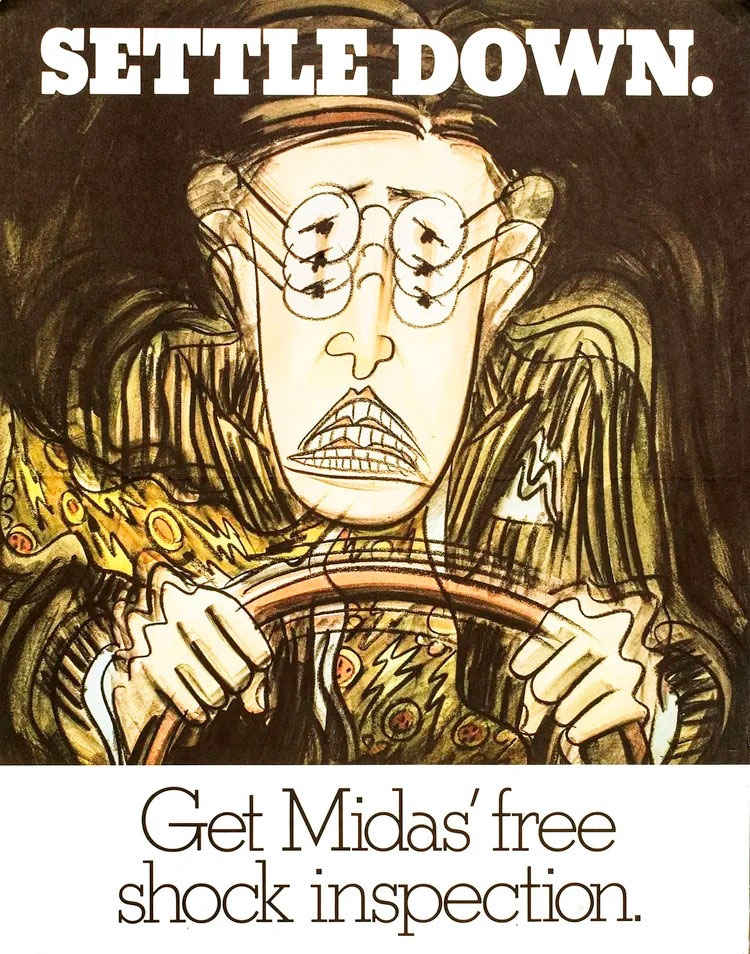

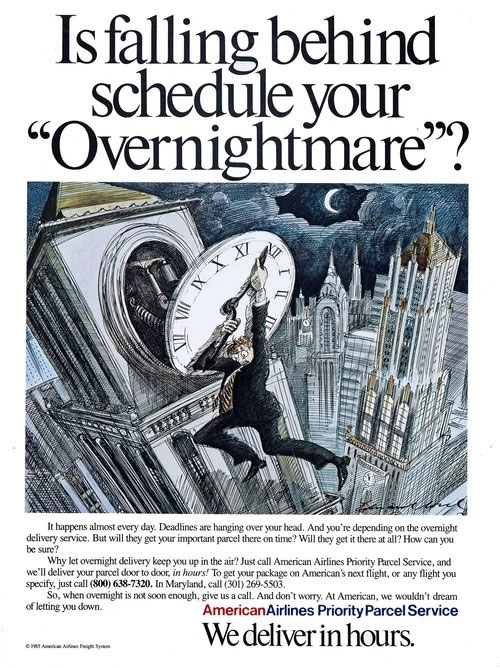

Advertisements by Edward Sorel.

Recognition

In 1973, Sorel was honored with the Augustus Saint-Gaudens Medal for Professional Achievement, given to him by the Cooper Union. In 1980, he received the George Polk Award for Satiric Drawing, and on 24 October 1987 he was also bestowed with the Page One Award for "Excellence in Journalism". In 1990, he added the Hamilton King Award from the Society of Illustrators to his trophy board. In 1993, Sorel received the National Cartoonist Society Advertising and Illustration Award. In 2001, he was honored with the Hunter College James Aronson Award for "Social Justice Journalism" and elected into the Art Directors Club of New York Hall of Fame. In 2002, he was bestowed with the Karikaturpreis der deutschen Anwaltschaft, on behalf of the Wilhelm Busch Museum in Germany. In 2014, he was inducted into the New York City Society of Illustrators' Hall of Fame.

In 1988, Sorel's caricatures were exhibited at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington D.C. The School of Visual Arts in Manhattan honored him in 2011, as part of their 'Masters' series. In 2022, he received the Reuben Award for Outstanding Cartoonist of the Year, on behalf of the National Cartoonists Society.

Legacy and influence

Sorel has also been active as a book and art critic, with his articles appearing in American Heritage, The New York Observer and The New York Times. In the early 1980s, Sorel taught art at Parsons and at SVA, each for one year. In the 2010s, he donated his entire archives to the Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center of Boston University. Edward Sorel has received admiration from veteran cartoonist Pat Oliphant. Novelist E.L. Doctorow (most famous for 'Ragtime'), named Sorel "our Honoré Daumier." He was also an influence on Jason Chatfield, Dave Cooper, Peter De Sève, Edward Koren and Adam Zyglis.

For those interested in Edward Sorel's life and career, 'Profusely Illustrated: A Memoir' (Alfred A. Knopf, 2021), is highly recommended. It is a combination of an autobiography, with more than 172 cartoons and illustrations to accompany his life story.

Self-portrait on the cover for Print - America's Graphic Design Magazine (January-February 1993). From left to right: Jimmy Carter, Henry Kissinger, Ronald Reagan, Lyndon B. Johnson, Richard Nixon, George Bush Sr., Gerald Ford and cardinal and archbishop of New York Terence Cooke.