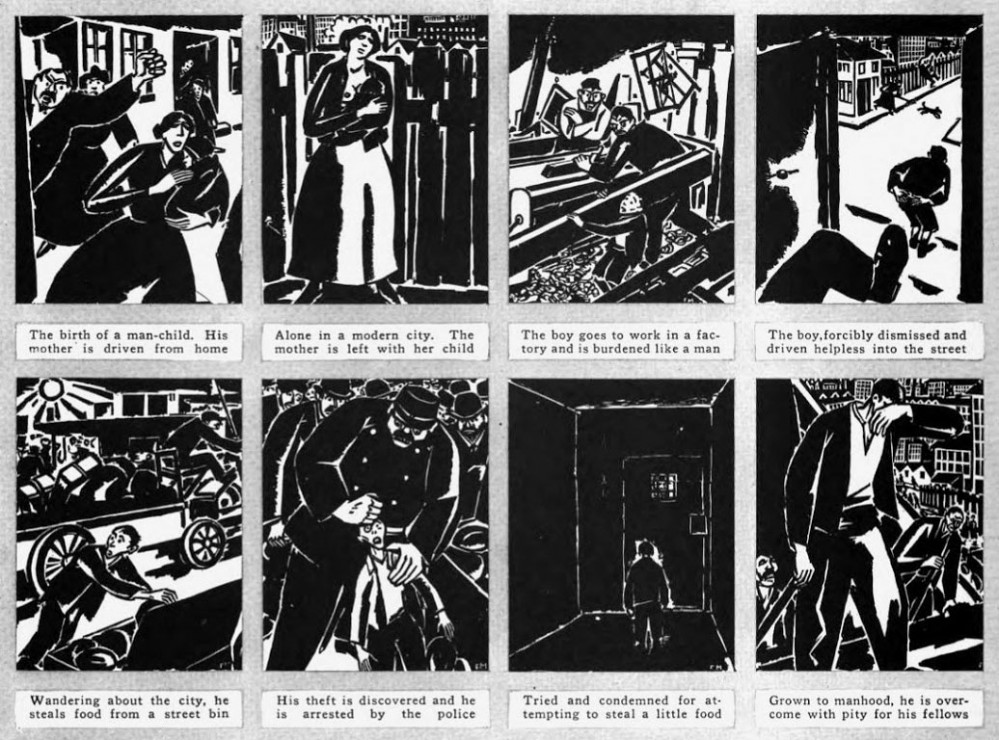

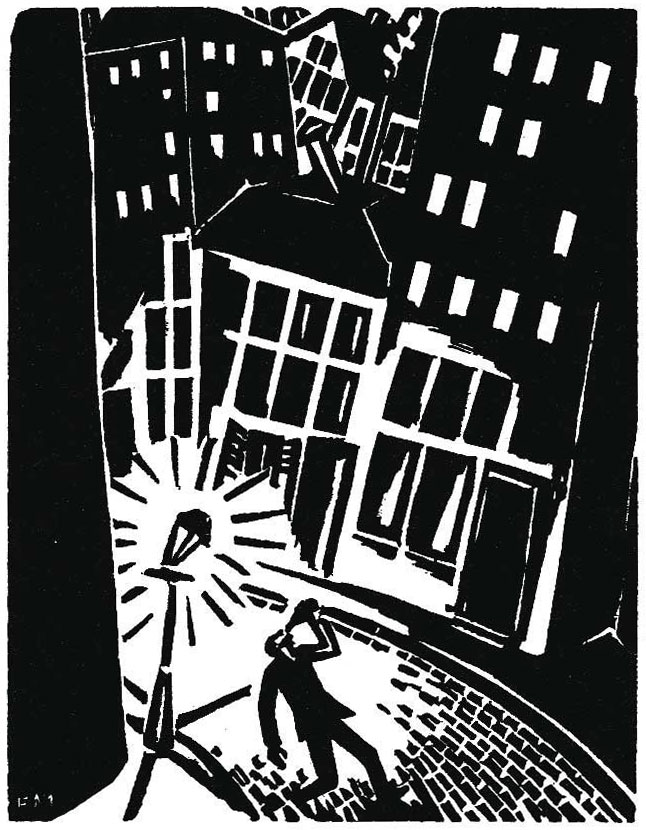

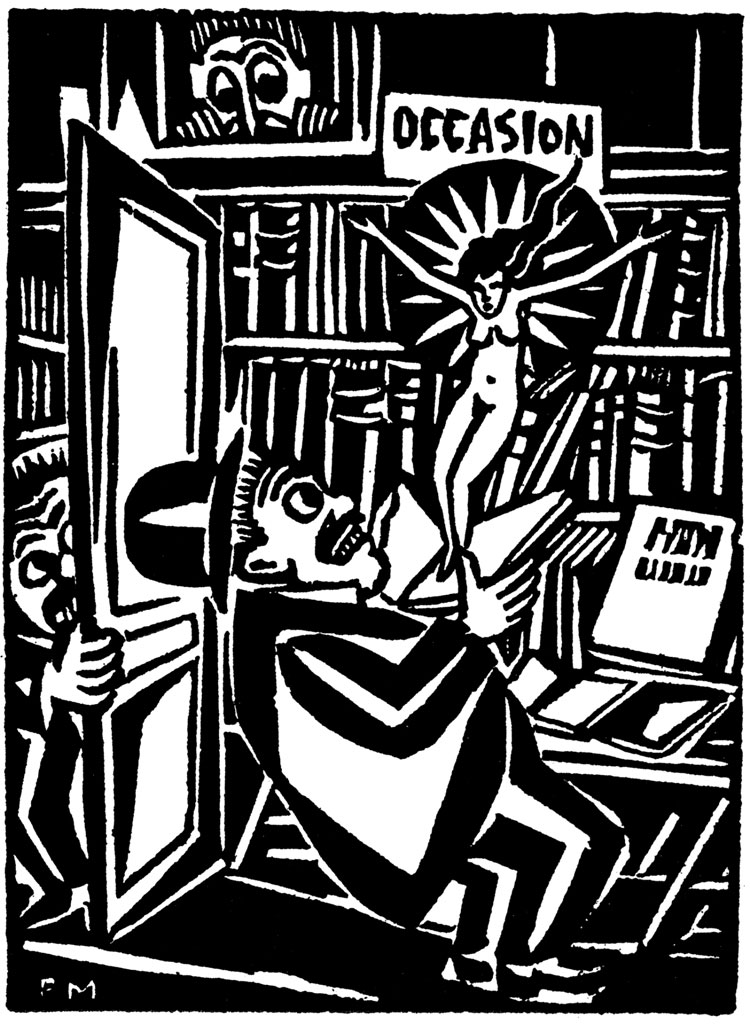

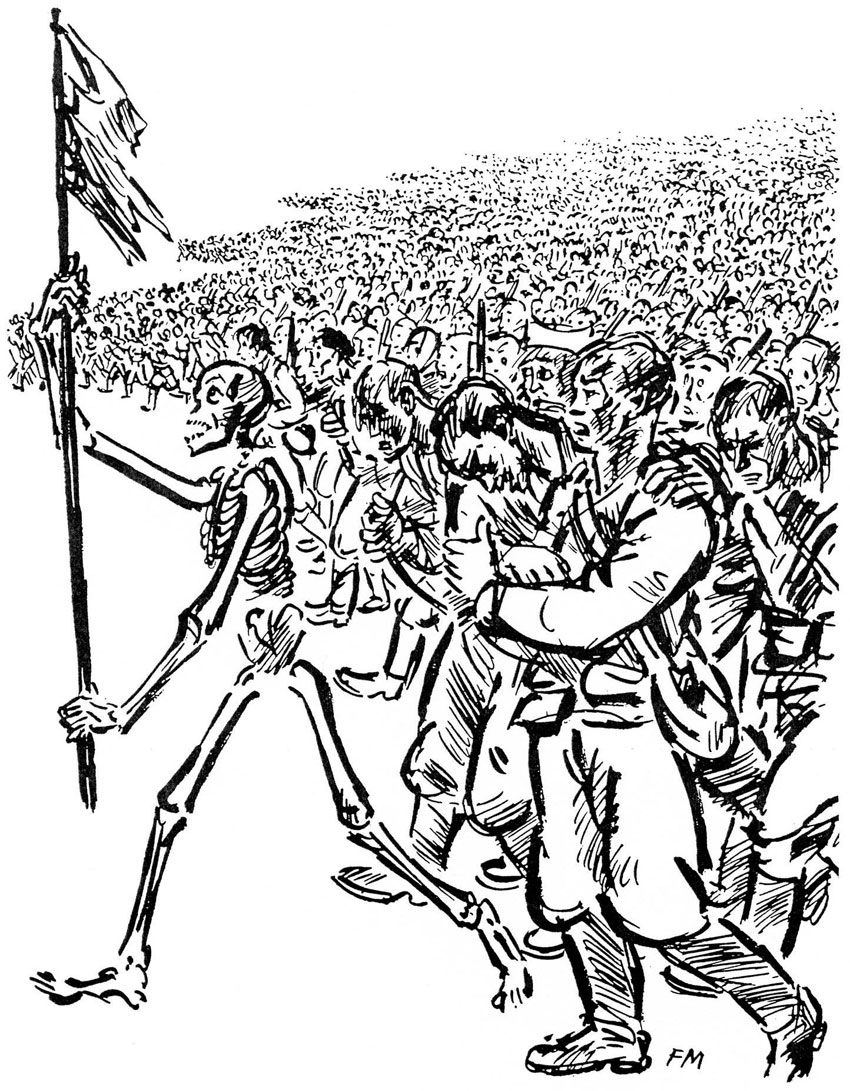

'25 Images of a Man's Passion' (Vanity Fair, February 1922).

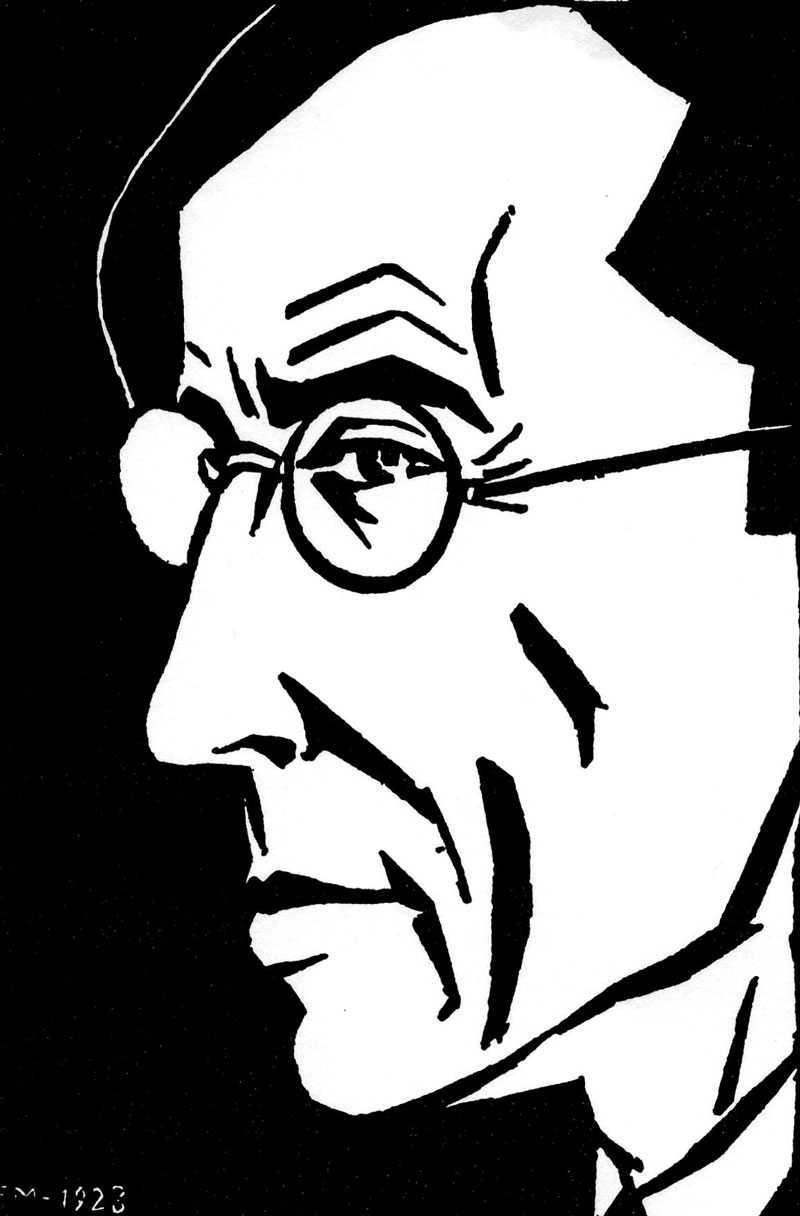

Frans Masereel was a globally influential Belgian graphic artist, widely recognized as a pioneer of the graphic novel. From the late 1910s until the late 1930s, he published several pantomime picture stories, using an expressionist woodcut technique. Deeply humanist, Masereel explored universal themes like pacifism, loneliness, creative urges and unrequited love. He depicted common people, lost in the impersonal "big city", misunderstood by higher powers and exploited by the System. In essence, Masereel pioneered the notion of a picture story as a personal, artistic statement, aimed at a mature audience. Already in his own lifetime, he influenced countless other illustrators and comic artists to make similar ambitious picture books. With titles like '25 Images de la Passion d'un Homme' (1918), 'Mon Livre d'Heures' (1919), 'Le Soleil' (1919), 'L'Idée' (1920), 'Histoire Sans Paroles' (1920) and 'La Ville' (1925), he laid the foundations of the modern-day graphic novel. His works continue to inspire artists to this very day.

Early life and career

Frans Laurent Wilhelmina Adolf Lodewijk Masereel was born in 1889 in the coastal town of Blankenberge. His father François came from a wealthy family, and lived off his interest. He was a widower and father of a ten-year old son when his first wife died in 1877. In 1887, he remarried to the 19-year old Louisa Vandekerckhove, with whom he had two more sons and a daughter, of which Frans was the oldest child. Like most rich Flemings at the time, Masereel's family spoke French, but used Flemish dialect when addressing their domestic staff. In 1894, the family returned to its city of origins, Ghent. Shortly afterwards, father François Masereel died at the age of 47, and in 1897, his mother remarried to the gynecologist Louis Lava, a prominent member of the liberal bourgeoisie, but above all a freethinker. From his piano-playing mother, Frans Masereel inherited his musical talent, and learned to play the cello at the local Music Conservatory. Although he began studies at the Royal Atheneum, he proved more practically oriented, and after only one year, he moved over to a Typography course at the local "School of the Book". An avid artist since his childhood, Masereel eventually enrolled at the Ghent Academy of Fine Arts, where from 1907 to 1910 the painter-sculptor Jean Delvin was one of his teachers. Through his stepfather, Masereel was introduced to the non-conformist and self-proclaimed proletarian painter/etcher Jules De Bruycker, whom he joined in his atelier and who became his mentor.

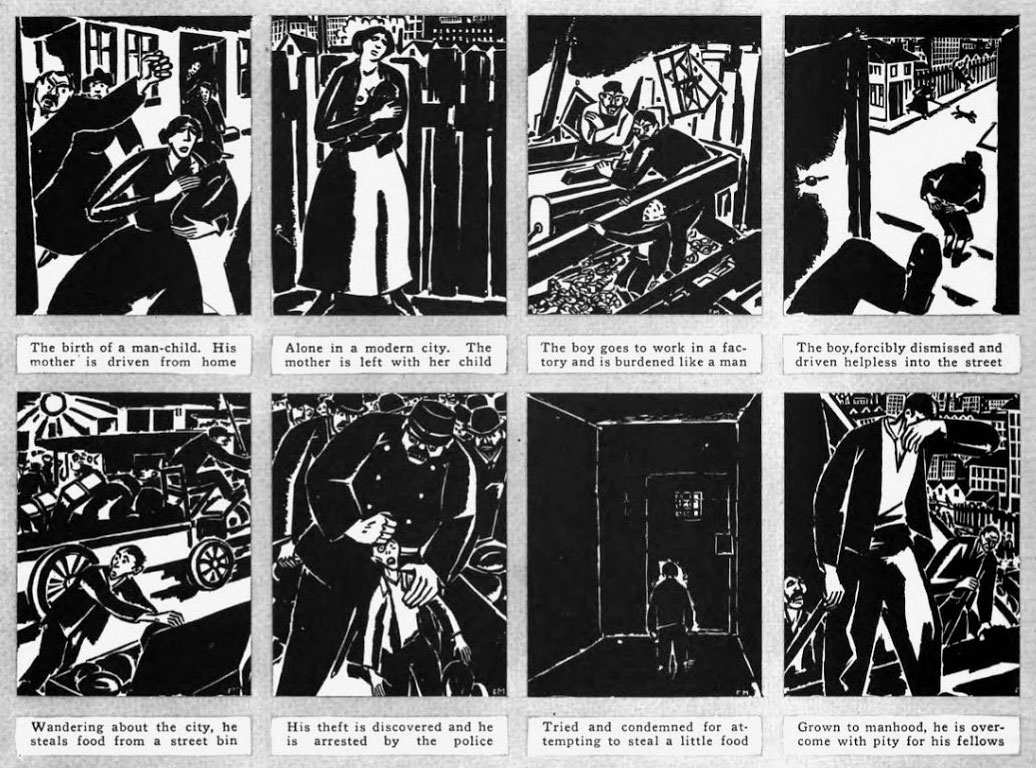

Artwork by Frans Masereel in Le Rire (1913).Translation: "Did you know that Bonnat lived in this studio before you?" - "Yes, old man, that's why I've had it disinfected!".

In Ghent, Frans Masereel observed the poor working conditions of the factory workers, and became involved in the socialist movement. Even though he came from a well-off family, Masereel developed progressive ideas about society and a rebellious streak. Important influences on his social viewpoints were the Flemish socialist leader Edward Anseele and the anarchist literature of the Russian writer Peter Kropotkin. Artistically, he found inspiration in the socially conscious cartoons in the French magazine L'Assiette au Beurre, singling out the cartoonists Théophile Steinlen, Jean Veber and Bernard Naudin. Developing a liberal approach to art, he tried several disciplines, including painting, sculpting, designing mosaics and theatre sets, and illustration. He however became best-known as an engraver, for which his main graphic influences were Albrecht Dürer, Grandjouan, Bernard Naudin and Félix Valloton.

His wealthy family background allowed Masereel to travel a lot. Between 1909 and 1911, he visited The Netherlands, France, Germany, England and Tunisia, before breaking off his studies and settling in Paris in 1911. In the French capital, he tried to get his work published in L'Assiette au Beurre, but was unaware that the magazine was about to fold. Chief editor Henri Guilbeaux encouraged him to continue his career, kicking off a lifelong friendship. Masereel's early artwork appeared in the column 'La Vie Illustrée' in the weekly Les Hommes du Jour. Masereel refined his woodcut skills under apprentice of Quatreboeufs, an artist friend of Bernard Naudin. In 1913, Masereel exhibited his work at the Salon des Indépendants, the notorious "alternative" counterpart of the more prestigious, but conventional Salon.

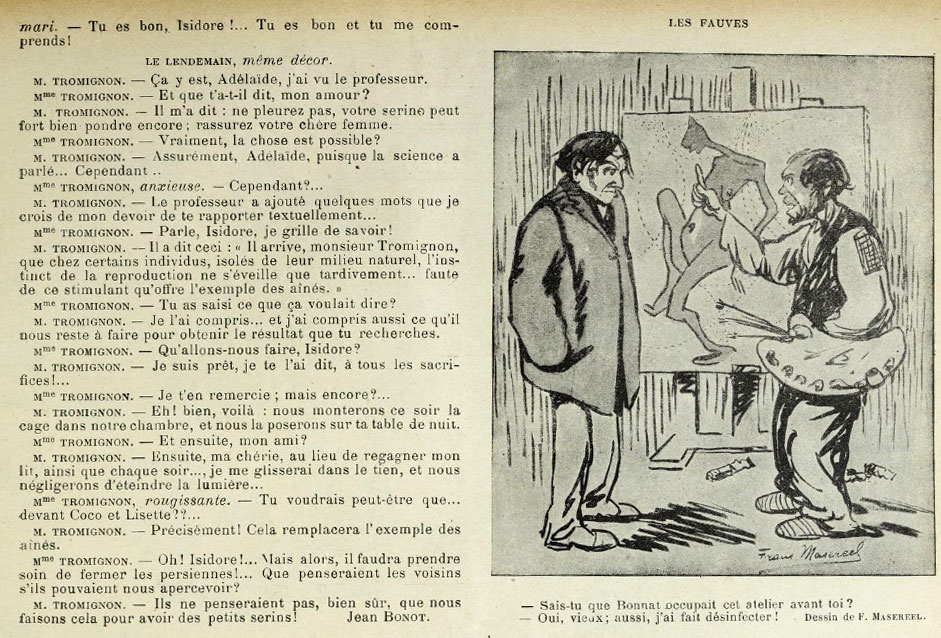

'Avant la Guerre' (from: La Grande Guerre Par Les Artistes, 1914–1916), a reflection on life before the First World War. Commoners are shown going to Mass, playing cards in a bar and dancing.

World War I

In 1914, the First World War broke out. As it happened, Masereel was on a holiday in Brittany (Bretagne) and quickly returned to Ghent. Since he was a lifelong pacifist, he refused to join the army. When the German military forces conquered Ghent too, Masereel fled back to Paris, by necessity largely on foot. During his journey, he made several drawings of refugees, war-torn buildings, while drawing anti-war illustrations, which were published in the magazine La Grande Guerre Par Les Artistes ("The Great War By Artists"). His patriotic art was also compiled in the book 'La Belgique Envahie' ("Invaded Belgium") by the Belgian journalist Roland de Marès. Nevertheless, Masereel didn't consider himself a patriot, since nationalism had been one of the main causes of the First World War.

World War I artwork by Frans Masereel.

In 1915, Masereel was able to flee to the Swiss city of Geneva, where his friend Henri Guilbeaux worked at the prisoner-of-war department of the local Red Cross. Masereel received a job as translator of letters by German and Flemish POW soldiers who couldn't speak French. He did several extra jobs on the side, for instance as a waiter. Although the war had exhausted his financial resources, Switzerland was at least a neutral country, allowing him to survive the war years in relative comfort. He befriended many fellow pacifists in Geneva, including French writer and Nobel Prize laureate Romain Rolland and the Austrian writer Stefan Zweig. For Guilbeaux' magazine Demain (1915), Masereel designed several anti-war woodcut illustrations. Together with the author Claude Le Maguet, Masereel established the monthly Les Tablettes, for which he made his 'Une Danse Macabre' woodcuts (1916), inspired by the 16th-century work of Hans Holbein the Younger. From 1917 on, Masereel made daily drawings for the pacifist newspaper La Feuille, as well as woodcut illustrations for Belgian poetry collection 'Quinze Poèmes' (1917) by Emile Verhaeren. He also published two anti-war books of his own, 'Debout les Morts' (1917) and 'Les Morts Parlent' (1917). Both make use of the woodcut technique.

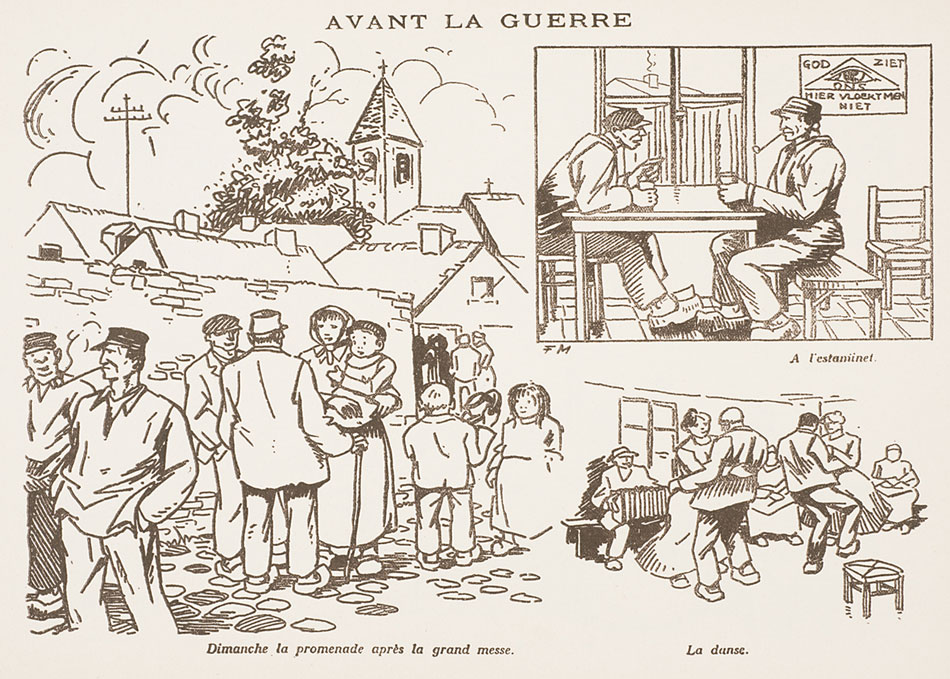

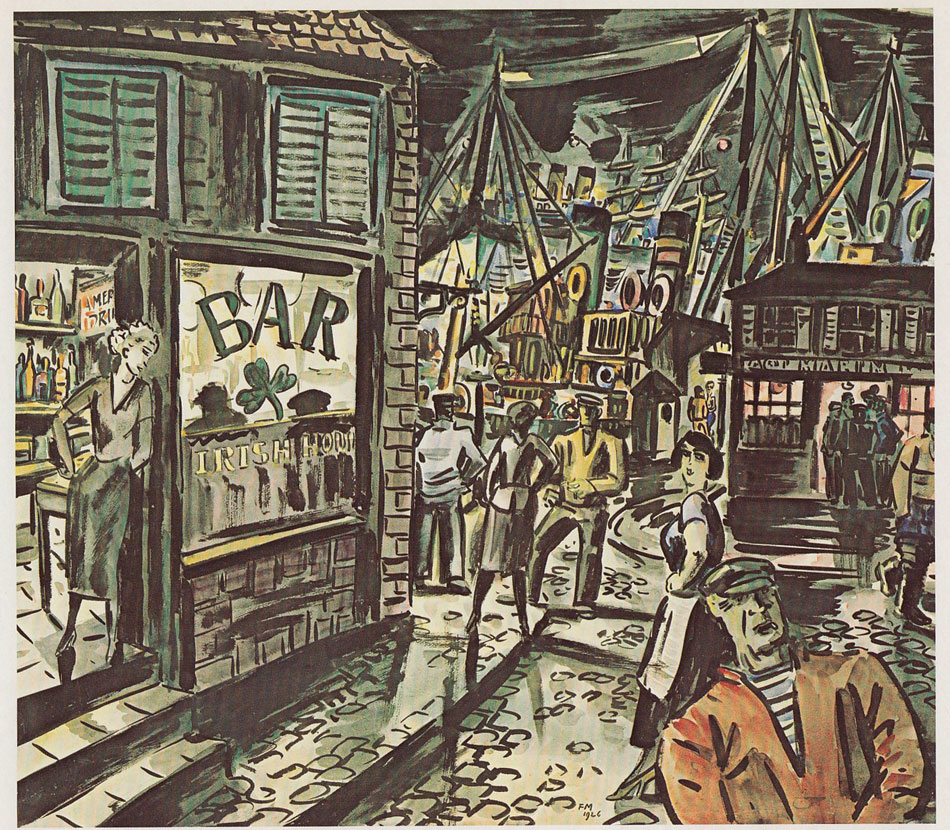

'Irish Bar' (watercolor painting, 1926).

Interbellum years

When the First World War ended in 1918, Masereel fell ill for a year, presumably due to the influenza pandemic known as the "Spanish flu". After recovering, Masereel and the French poet René Arcos established the publishing company Le Sablier, which would release all of Masereel's publications until 1921. On 26 June 1919, Masereel and another poet, Romain Rolland, released the manifesto 'Déclaration d'Indépendance de l'Espirit' ('Declaration of the Independent Mind'), encouraging artists to be independent from politicians and the masses and express their social consciousness in their art. The document was also distributed to Belgium ('L'Art Libre') and Germany ('Demokratie und Forum'). Apart from Rolland and Masereel, it was signed by several European intellectuals, including scientist Albert Einstein, philosopher Bertrand Russell and novelists Hermann Hesse (of 'Der Steppenwolf' fame) and Selma Lagerlöf (of 'Nils Holgersson' fame).

Still based in Geneva, Masereel was also a member of the Antwerp-based Belgian artistic group Lumière, which promoted woodcut printing and pacifism through its magazine of the same name. Chief editor Roger Avermaete was impressed by the Sablier publications of Masereel, and asked him to contribute to the magazine as well. Through correspondence, Masereel became one of the main contributors to the Lumière projects, along with the other core members Joris Minne, Henri van Straten and the brothers Jan Frans and Jozef Cantré.

By 1922, most of Masereel's refugee friends in Geneva had returned to their homelands. He couldn't do the same, since the Belgian army considered him a draft dodger, due to his pacifist actions. Instead, Masereel returned to Paris, where he remained for the rest of the 1920s and 1930s. In 1922, he married his longtime girlfriend Pauline Imhoff. In addition to working in the French capital, he opened a studio in a fisher's house in the dunes of Équihen, not far from the town Boulogne-sur-Mer, where he often went during summers.

Although in the early 1920s Masereel was persona non grata in his home country, his international stature grew. From 1928 on, he was a frequent contributor to the French cultural magazine Le Monde. All over Europe, and even as far as the United States, Russia and Brazil, his work was published and exhibited. In New York, his picture stories were serialized in Vanity Fair magazine. In the 1920s, Masereel's work received tremendous critical appreciation in Germany, not surprisingly in the birthplace of Expressionism.

Masereel's socially conscious activism was also lauded by pacifist and anti-fascist organisations. In 1932, he co-organized the International Congress Against War and Fascism in Amsterdam. In 1935 and 1936, he released 'Capitale' (1935), condemning capitalism and fascism, and visited the Soviet Union twice. During his second trip, he met the German playwright Bertolt Brecht, the American actor and singer Paul Robeson and the French writer André Gide, who afterwards expressed his disillusionment with Soviet ideals in the book 'Retour de l'USSR'. In 1937, Masereel was also in Spain during the Spanish Civil War.

By the mid-1920s, his fellow countrymen re-embraced him. In 1926, his art was exhibited in the Brussels gallery Le Centaure and by 1929 he received a new Belgian identity card. Still, Masereel never moved back to the country of his birth.

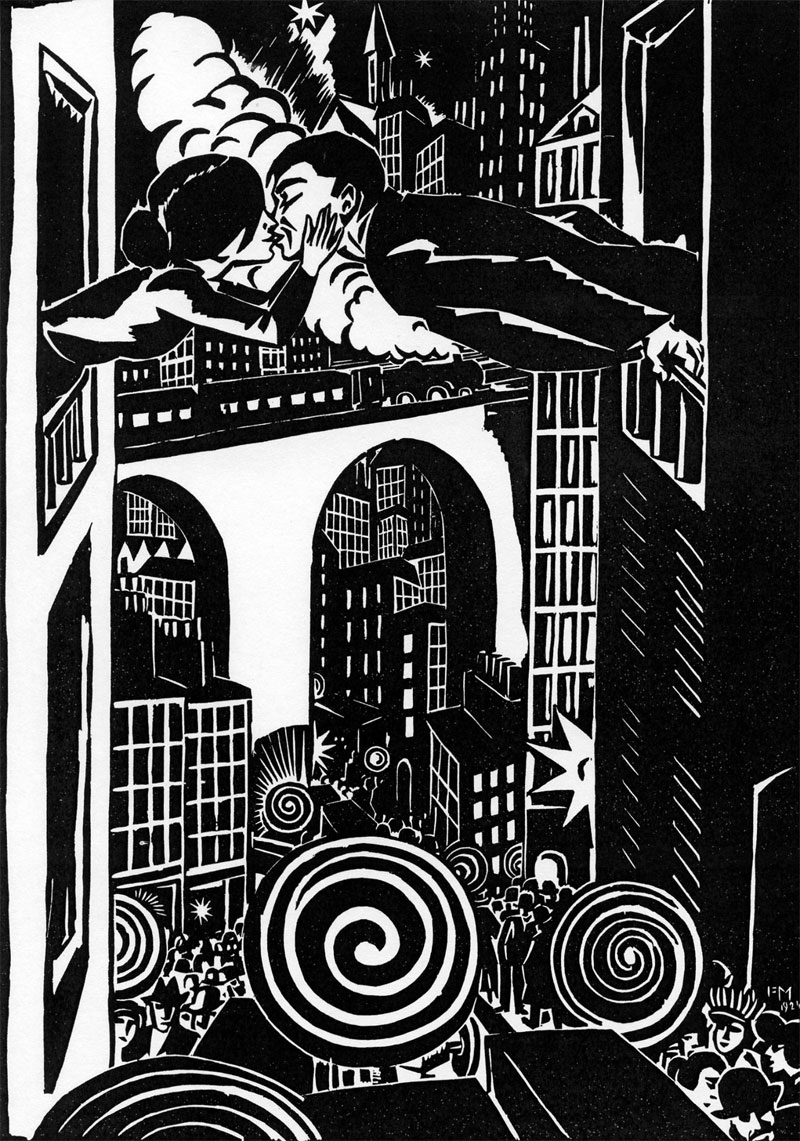

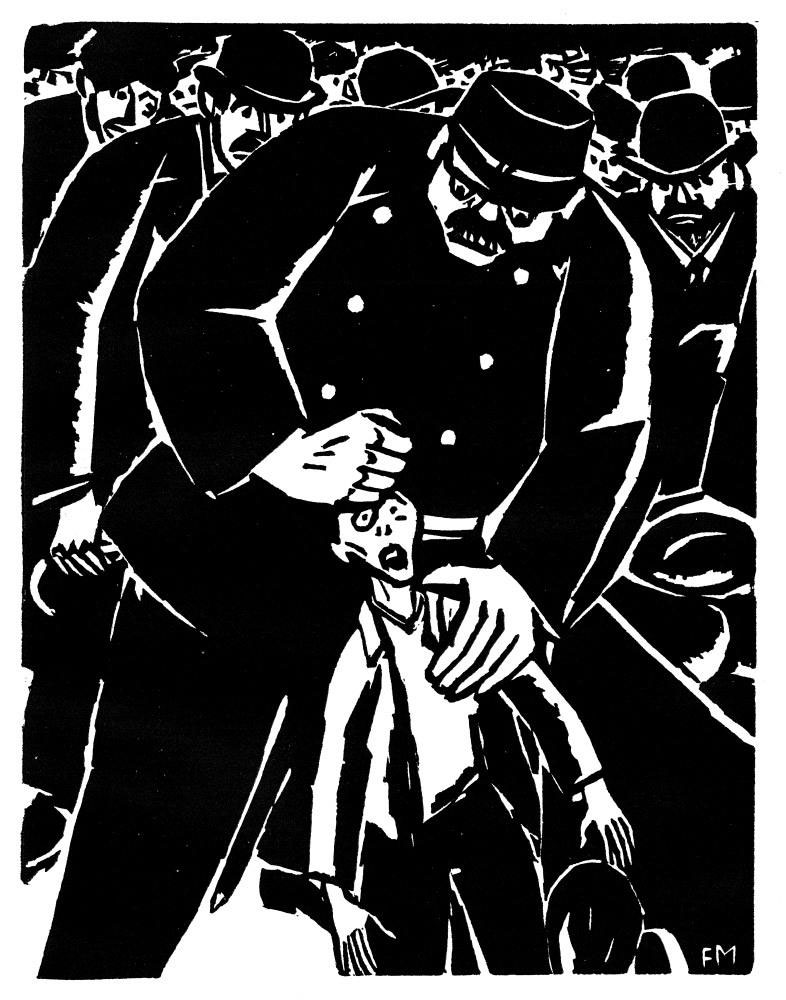

'25 Images de la Passion d'un Homme' ('25 Images of a Man's Passion', 1918).

25 Images de La Passion d'un Homme

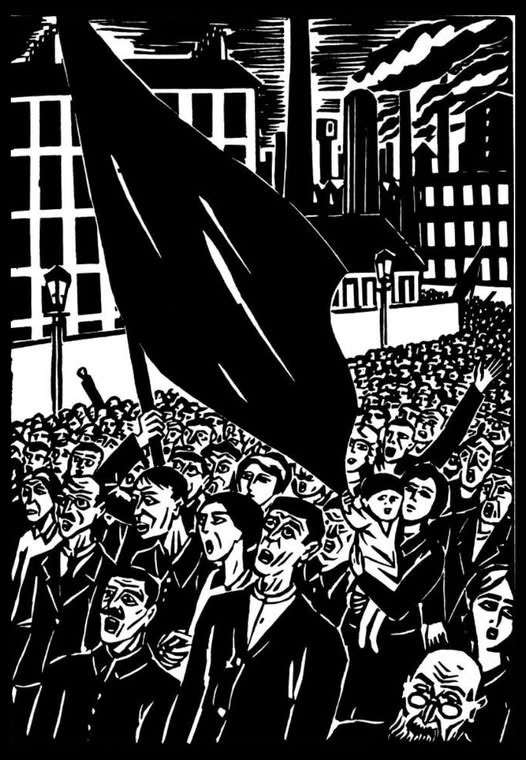

From 1918 on, Masereel released various innovative books with woodcut-printed narrative images, which can be considered precursors to present-day graphic novels. Named "visual suites", the books had one image per page, no dialogue and socially conscious themes. The first was '25 Images de la Passion d'un Homme' ('25 Images of a Man's Passion', 1918). The book consists of 25 images, without dialogue. The protagonist is a young man, born into misery. His mother is not his biological parent and rejects him. The man leads a life of debauchery, to compensate for his low-paid job. Eventually he wisens up and decides to not take it any longer. He educates himself and rallies his co-workers to rise up against his boss. But instead of a revolution, his plans are thwarted. The authorities arrest him and have him executed.

'25 Images de la Passion d'un Homme' ('25 Images of a Man's Passion', 1918).

'25 Images' was a remarkable work for its time. In previous centuries, picture stories and illustrated narratives had become a common phenomenon. Masereel was particularly inspired by medieval religious picture stories, which told biblical tales and the lives of saints through visuals since most people at the time couldn't read. In a sense, the protagonist in '25 Images' is comparable to a Messianic martyr, "crucified" for his beliefs. The title itself references the Passion of Christ story. But Masereel's tale is still different from a religious morality tale. It can't be compared with a retelling of a historical event, nor a humorous tale. The story is pure fiction, set in the modern age and drenched in Masereel's socialist ideals. Despite being born in an upper-class family, Masereel never forgot the dire circumstances in which the textile factory workers in Ghent had to slave away their existence. '25 Images' shows his immense compassion with the suppression of the common man. Contrary to other picture stories of time, it wasn't distributed through sheets, nor serialized in a magazine. Instead, Masereel published '25 Images' in a novel format.

'25 Images' struck a chord with many readers, especially in a time when activists and unions strove for workers' rights, while Russia became a Communist state. The book appeared in several languages, including German ('Die Passion eines Menschen', 1921), and its images were bootlegged on many posters and pamphlets by workers' movements, especially the panel in which the protagonist waits for his execution. In February 1932, '25 Images' was serialized in the American magazine Vanity Fair, though in a text comic format, with narration underneath the images. These captions were added by the editors, seemingly convinced that readers would otherwise be unable to understand the visuals.

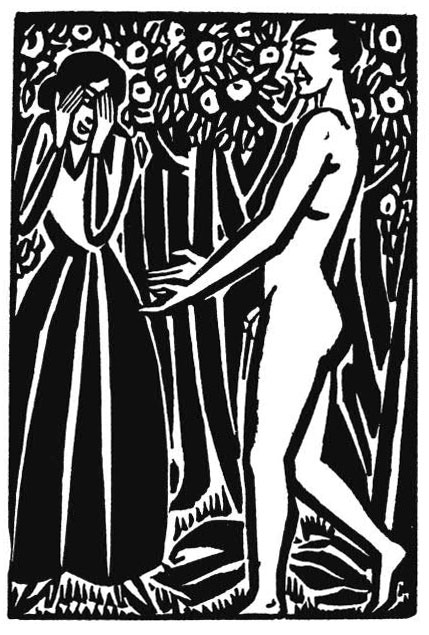

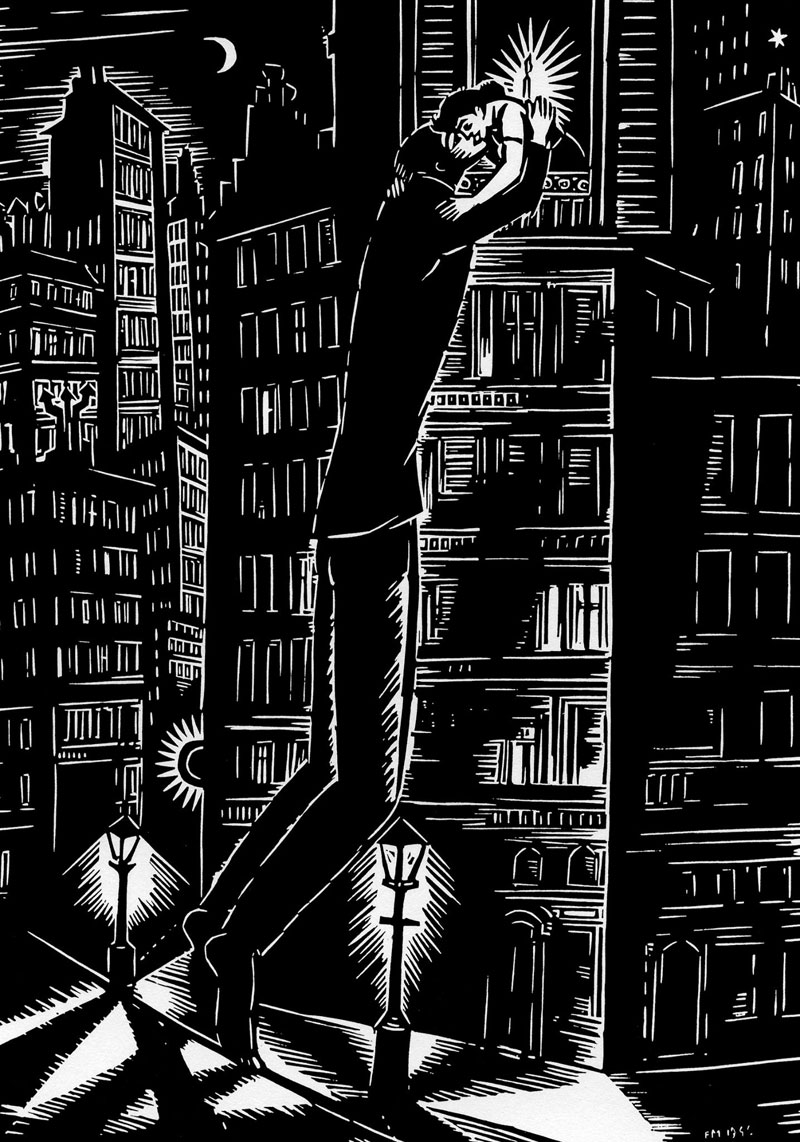

'Mon Livre d'Heures' ('Passionate Journey', 1918). This image has sometimes been censored in reprints and translations.

Mon Livre d'Heures

In the following year, Masereel released a more ambitious picture story, 'Mon Livre d'Heures' ('Passionate Journey', 1919). Using more than 167 woodcuts, it is effectively his longest story. The title refers to the medieval literary genre "book of hours", in which chronological events were visualized and marked by the different hours of the day when people were expected to pray. 'Mon Livre d'Heures' reflects on key moments in a man's life. The protagonist travels to the city, which both enthralls and disgusts him. He enjoys drinking, partying and whoremongering, but, at the same time, also feels lost amidst the crowds, the high-rising buildings and the traffic of the "modern city". The man works in a factory and eventually flees the metropolis, finding emotional relief in the tranquility of nature. There, he dies in the woods, with his skull-faced spirit rising from his corpse, flying off into the cosmos.

'Mon Livre d'Heures' ('Passionate Journey', 1919).

For Masereel, 'Mon Livre d'Heures' was a more personal, semi-autobiographical story. Given that he had lived in foreign cities and towns ever since leaving Belgium in the early 1910s, Masereel knew like no other how alienating and impersonal this experience could be. The book summarized all of his existential feelings. Although the work was very contemporary and based on realism, Masereel also started using exaggerated imagery and fantastical metaphors. Buildings are tilted, body parts are enlarged and backgrounds can visualize characters' emotions.

'Mon Livre d'Heures' was an instant success, receiving translations in English ('My Book of Hours' or 'The Passionate Journey' in the USA), German ('Mein Stundenbuch'), Russian and Chinese. Romain Rolland wrote the foreword for the 1922 American edition and Thomas Mann for the 1928 German edition. However, in some foreign editions two "obscene" scenes were removed, namely a sex scene with a prostitute and another in which the protagonist literally pisses on the city.

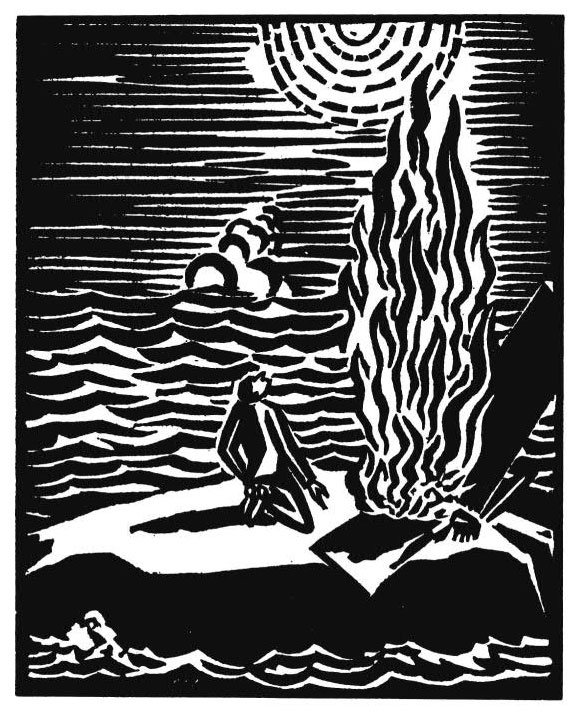

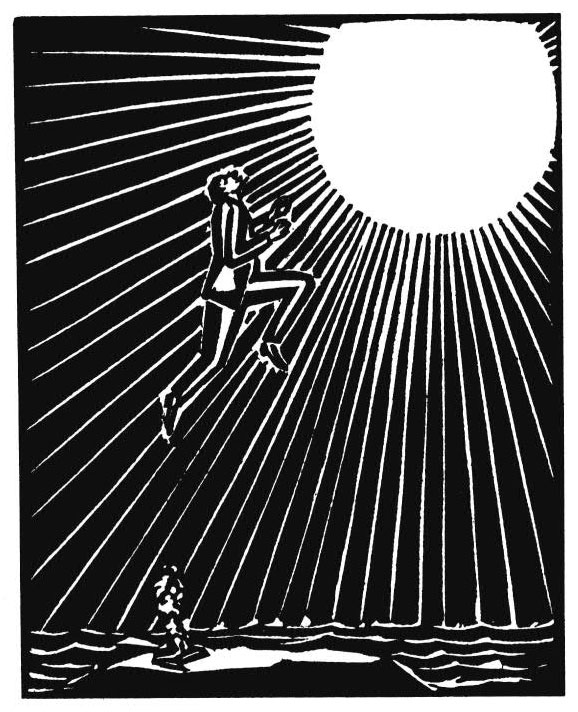

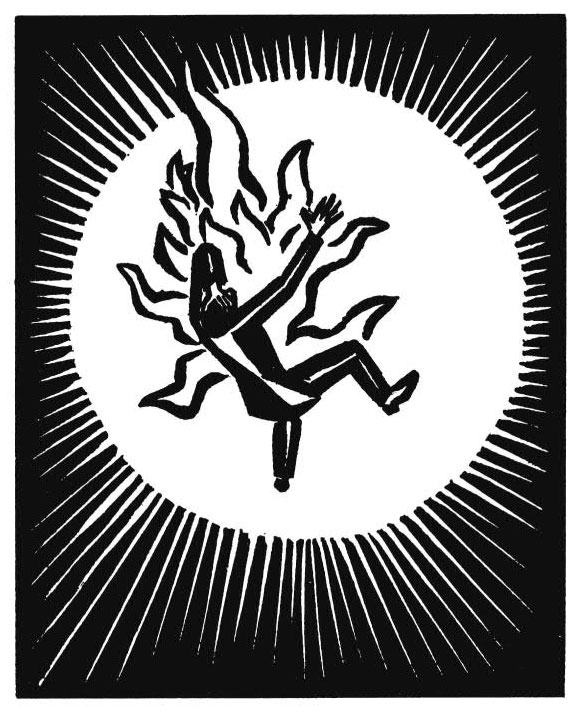

Le Soleil

With 'Le Soleil' ('The Sun', 1919), Masereel made a 63-woodcut metafictional story. It starts off with an artist falling asleep behind his desk. As he slumbers, a tiny man crawls out of his head and wanders off into the world. People try to discourage and distract him, but his aspirations drive him away from this peer pressure. Instead, he climbs on the highest possible trees, buildings and objects, trying to reach the Sun. Much like the Greek mythological character Icarus, the tiny man nearly burns himself and plummets back to Earth. At that precise moment, the artist wakes up, scratching his head in bewilderment.

'Le Soleil' has been interpreted as an allegory for human imagination and freedom of expression. Ideas have no limits and can give people hope and power. But even the most wonderful ideas often get stuck on the boundaries of reality. The work is additionally seen as a metaphor for the bond between creator and creation. 'Le Soleil' was translated into German ('Die Sonne', 1920) and English ('The Sun'). In 1949, Belgian novelist Louis Paul Boon wrote a personal reflection about Masereel's drawings, published in the Communist magazine De Roode Vaan.

Idée

Masereel's 'Idée, Sa Naissance, Sa Vie, Sa Mort: 83 Images, Dessinées et Gravées Sur Bois' ('The Idea, Its Birth, Its Life, Its Death: 83 Images, Drawn and Engraved on Wood', 1920) is a companion piece to 'Le Soleil'. Again, an artist gives birth to an idea, personified as a tiny human, only this time a naked woman. When he tries to represent it to the outside world, the authorities try to suppress her. One civilian tries to defend her, but is taken away and executed. Despite all the attempts to remove the idea, she survives and manages to reproduce herself in the mass media. Masereel closes off with the artist having another creative thought, this time a white-haired woman, whom he releases into the world.

'Idée' has been interpreted as a metaphor for the power of thought. No matter how much society tries to ignore, deny or fight ideas, they cannot be suppressed. By visualizing ideas as nude women, they may represent particularly bold and progressive thoughts that are initially too confrontational for the conventional masses and powers, but eventually find more widespread acceptance. As an artist, Masereel could relate. He once named 'Idée' his personal favorite story. 'Idée' has also been viewed as a feminist parable. A free-spirited woman tries to find her way in a male chauvinist society. Her nudity symbolizes her femininity, which sexist authorities use as an excuse to censor her.

'L'Idée' appeared in Dutch ('Het Idee'), German ('Die Idee', 1924) and English ('The Idea', 1986). The 1927 German-language reprint came with a foreword by the German novelist Hermann Hesse. 'L'Idée' was also adapted into a 1931 animated short by the Austrian film director Berthold Bartosch, with a soundtrack by Arthur Honegger. Masereel originally collaborated with the film adaptation, but later left the project when Bartosch made the ending more tragic by letting the authorities win. The short is notable for its experimental animation, mature themes and as, arguably, the first known example of a graphic novel film adaptation.

'Histoire Sans Paroles' ('Story Without Words', 1920).

Histoire Sans Paroles

In 1920, Masereel released 'Histoire Sans Paroles' ('Story Without Words', 1920). The plot is simple and straightforward: a man goes through great lengths to seduce a woman. His attempts lead nowhere, until he threatens to kill himself. Taking pity on him, she gives him a chance and the couple ends up in bed together. The woman now loves her new partner, but he no longer wants anything to do with her and leaves her behind, crying. 'Histoire Sans Paroles' is a timeless tale about unrequited romance. While the reader understandably sympathizes with the female character, the man isn't a heartless bastard either. In the final images, he too shows regret and disappointment about breaking off their bond. From this perspective, the story has been interpreted as a metaphor for obsessive fixation and the unavoidable disappointment once the goal has been achieved, since it can never entirely live up to the expectations.

The 60-panel story is notable for its imaginative backgrounds that visualize the characters' feelings. When the man shows off his strength, circus strongmen appear behind him. His attempt to sing a love song is ridiculed by the appearance of a crow and a rooster, birds not known for their beautiful voices. When he threatens to kill himself, skeletons dance in a graveyard. 'Histoire Sans Paroles' appeared in German under the title 'Geschichte ohne Worte' (1922), with an epilogue written by novelist Hermann Hesse. Decades later, it also received an English-language edition as 'Story Without Words' (1986).

'La Révolte des Machines où La Pensée Déchainée' ('The Machine Revolt, or the Unchained Thought').

La Révolte des Machines

Together with Romain Rolland, Masereel envisioned a satirical film about the dangers of industrialisation, 'La Révolte des Machines où La Pensée Déchainée' ('The Machine Revolt, or the Unchained Thought'). The plot features machines rising against mankind, creating havoc and destruction. Masereel made several typeface woodcuts, intended as a storyboard, but the film never went into production. Instead, 'La Révolte des Machines' (1921) was published by Le Sablier in a limited book edition. Technically an illustrated novel, Masereel's images are sometimes presented as comic strip-like sequences. In 1923, it was also serialized in the American magazine Vanity Fair.

Grotesk Film

In 1921, Masereel made another "cinematic" book, 'Grotesk Film', written by Israel Ber Neumann. The work is a reflection on mankind and, tellingly, drawn in a far more caricatural style than Masereel's other works.

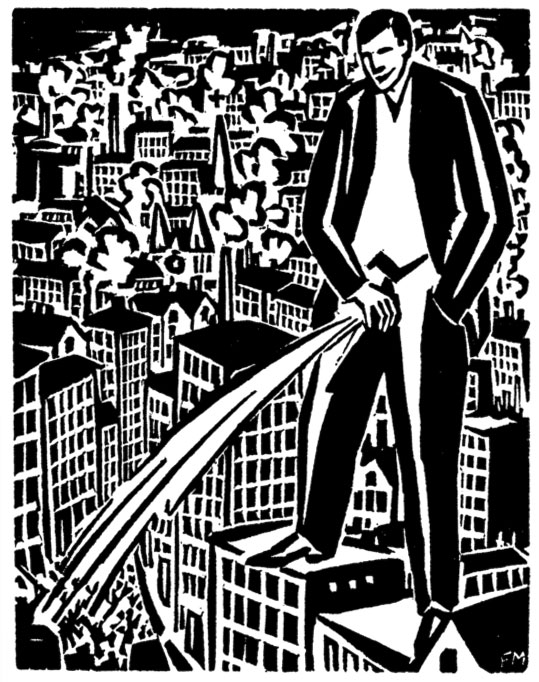

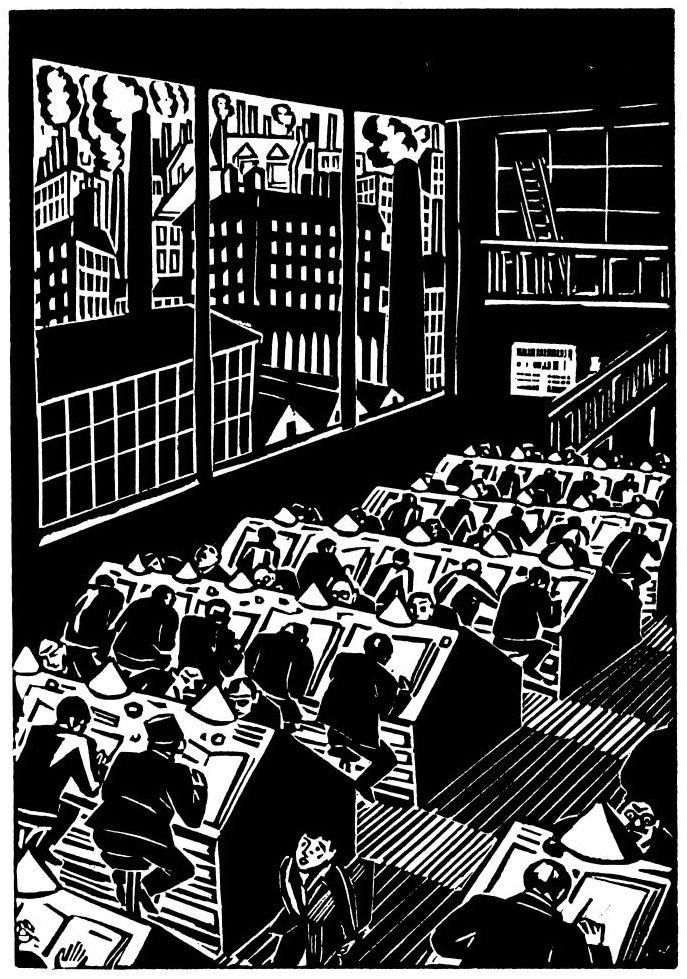

La Ville

In 1925, Masereel published 'La Ville' ('The City', 1925), a print book with 100 woodcuts, often cited as his final masterpiece. Sometimes ranked among his other graphic novels, 'La Ville' differs in the sense that it doesn't have a genuine plot, or recurring characters, only an overall theme. It's a series of individual vignettes, all set in a generalized city. The ambitious work celebrates the exuberance of the city, always moving, always busy. People gather together at parties, in bars and restaurants. There are job opportunities and ways to experience pleasure. Some images are poetic in tone. Fireworks brighten up the sky. Ships pass by under a bridge. A woman looks at the night sky out of her window. At the same time, Masereel also presents the high-rise buildings and hectic rushing as a claustrophobic, impersonal "modern jungle". Between the towering flats, narrow streets and thick crowds, people can feel lonely and insignificant. The artist doesn't shy away from showing the seedier parts of urban existence. People fight in a bar. Horny men visit brothels. Workers slave away in the shade of polluting factories. Beggars hope for the sympathy of passersby. Pickpockets sneak up everywhere. A man hangs himself in his lonely room. A dead woman is dragged out of a canal.

'La Ville' ('The City', 1925).

'La Ville' is the apotheosis of Masereel's grim reflections on the metropolis. Being born in a small Flemish town, living in big cities like Paris and Geneva was an overwhelming experience for him. He covered similar themes in '25 Images' (1918) and 'Mon Livre d'Heurs' (1919), but in 'La Ville' individualism has been obliterated by the anonymity of city life. Nobody in 'La Ville' is more or less important than the others. Some people enjoy the anonymity, tip-toeing to prostitutes, grabbing purses or doing other shady activities. Others live in ragged-down flats, trying to make it to another day, while nobody cares about their fate. While timeless in its themes and images, 'La Ville' has also become an unintentional time capsule of 1920s city life.

The work has appeared in German ('Die Stadt', 1925), Dutch ('De Stad', 1962), English ('The City', 1972), Italian ('La Città', 1979) and Spanish ('La Ciudad', 2009).

'La Ville' ('The City', 1925).

Further woodcut collections

Other Masereel woodcut collections of the 1920s were shorter and less sequentially driven. Inspired by the human interest sections from the newspapers, Masereel's woodcut set 'Un Fait-Divers' (1920) told the story of an innocent girl, who is seduced, impregnated and then abandoned, after which she jumps off a bridge in desperation. In May 1921, Masereel released 'Souvenirs de Mon Pays', in which the artist reflected with melancholy and tender irony on his childhood in Blankenberge. He dedicated the book to his mother. One set of woodcuts that Masereel released through the Lumière group was 'Visions' (1921).

World War II

Unsurprisingly, Masereel's modernist art and pacifist, anti-fascist statements made him highly unpopular in Nazi Germany. From 1933 on, his art and books were banned, burned and exhibited during the "Entartete Kunst" ("Degenerate Art") expos, alongside other modern and experimental artists. When Hitler invaded Paris in 1940, Masereel again fled on foot, walking all the way to Orléans. A wise decision in retrospect, since his studio in Équihen was plundered and many of his works destroyed. In 1941, he settled in Avignon, where he had an affair with a fellow painter named Laure Malclès. During this period, he made several anti-Nazi pamphlets, drawings and engravings for the French Resistance, among them 'Juin 1940' (1942). The Resistance expressed their gratitude by making a false passport for him, allowing him to move to Lot-et-Garonne under the identity of "Françóis Adolphe Laurent", where he spent the remainder of the war.

Book illustrations

In addition to his own books, Masereel also provided a great many book illustrations, mostly for his author friends. His art decorated the pages of French authors like Charles-Louis Philippe ('Bübü vom Montparnasse', 1920), René Arcos ('Das Gemeinsame', 1920), Henri Barbusse ('Quelque Coins du Coeur', 1921), Blaise Cendrars ('Les Pâques à New York', 1926), Louis Piérard ('Ode à la France Meurtrie', 1940) and Agrippa d'Aubigné ('Jugement', 1941). He also livened up works by German and Austrian authors, including Leonhard Frank ('Die Mutter', 1919), Andreas Latzko ('Le Dernier Homme', 1920), Carl Sternheim ('Chronik von des zwanzigsten Jahrhunderts Beginn', 1922, 'Fairfax', 1922), Stefan Zweig ('Der Zwang: Phantatische Nacht', 1929), Ernst Preczang ('Im Strom der Zeit: Gedichte', 1929) and Rudolf Hagelstange' ('Die Nacht', 1955). Masereel's illustrations were also in demand among Dutch authors like Theun De Vries ('Dolle Dinsdag', 1967) and Flemish ones like August Vermeylen ('Der ewige Jude', 1921), Maurice Maeterlinck ('Le Trésor des Humbles', 1921), Stijn Streuvels ('Kerstwake', 1928, 'De Vlaschaard', 1965), Herman Teirlinck ('De Man Zonder Lijf', 1937), Achilles Mussche ('Aan de Voet van het Belfort') and Jos Vandeloo ('Schilfers hebben Scherpe Kanten', 1974).

Masereel was practically the house illustrator of three specific authors: Pierre Jean Jouve ('Hôtel-Dieu, Récits d'Hôpital', 1915, 'Heures', 1919, 'Cygne de Rabindranath Tagore', 1923 and 'Prière', 1924), Émile Verhaeren ('Quinze Poèmes', 1917, 'Le Travailleur Étrange et Autres Récits', 1921, 'Cinq Histoires', 1924), Johannes R. Becher ('Du bist für alle Zeit geliebt. Gedichte', 1960, 'Vom Verfall zum Triumph', 1961) and Romain Rolland ('Peter und Lutz', 1921, 'La Révolte des Machines ou la Pensée Déchainée', 1921, 'Liluli', 1924, 'Jean-Christophe', 1925).

He also illustrated new editions of older, more classic books, like Walt Whitman's 'Calamus' (1919), Oscar Wilde's 'The Ballad of Reading Gaol' (1923), Rudyard Kipling's 'The Seven Seas' (1924), Guy de Maupassant's 'Le Horla et Autres Contes' (1928), François Villon's 'Le Testament' (1930), Victor Hugo ('Notre-Dame de Paris', 1930, 'Die Arbeiter des Meeres', 1944), Leo Tolstoy ('The Master and his Servant', 1930), William Shakespeare ('Hamlet', 1943), Charles De Coster's 'Thyl Uilenspiegel' (1943), Charles Baudelaire's 'Les Fleurs du Mal' (1946 edition), Émile Zola's 'Germinal' (1947), Ernest Hemingway's 'The Old Man and the Sea' and the first 8 chapters of 'The Book of Genesis' (1948).

Graphic contributions

Masereel illustrated the pacifist poetry collection 'Les Poètes Contre La Guerre' (1920), written by Romain Rolland, Georges Duchamel, Charles Vildrac and Pierre-Jean Jouve. In addition, he designed the Belgian pavilion at the 1937 World Exhibition in Paris, as well as sets and costumes for Jean Cocteau's film 'Le Machine Infernale' (1932) and Bertolt Brecht's play 'Furcht und Elend des Dritten Reiches' (1943). In 1949, he created a large mosaic facade for the Villeroy & Boch building in Mettlach, Germany.

Recognition

In 1950, Masereel received the Grand Prize of Graphic Arts at the 25th Venice Biennale. He was also a member of the Belgian Royal Academy of Science, Literature and Fine Arts. The Deutsche Akademie der Künste named him a corresponding member in 1957. The Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität handed him the Joost van de Vondelprijs (1962), while he and Ernest Bloch shared the first Cultural Award of the Deutsche Gewerkschaftsbund in Düsseldorf (1964). In 1969, the Humboldt University in East-Berlin named Frans Masereel doctor honoris causa. He additionally won the Achille van Acker Award (1971).

In 1951, Pablo Picasso held a Masereel exhibition in the Grimaldi castle in Antibes. In 1958, the Association du Peuple Pour Les Relations Culturelles Avec L'Étranger organized several exhibitions of his work in the Chinese cities Peking, Shanghai and Wuhan. Masereel was no stranger to the Chinese. During the 1930s, bootleg copies of his art were already in circulation there.

Post-war years and death

After World War II, Masereel returned to Avignon, moving to Nice in 1949. Between 1947 and 1951, he worked as a teacher at the Hochschule der Bildende Künste in the German city of Saarbrücken. Masereel later took a job as a librarian of the public welfare commission, allowing him to only work in the mornings. His later years were marked by health decline. In 1951 and 1953, he was operated on respectively his left and right eye. In 1961, he slipped on the sidewalk and broke his right leg. He died in 1972, at age 82. Masereel's remains were brought to Ghent, where he received a funeral service fit for an artist of his reputation, attended by Flemish Minister of Culture Frans Van Mechelen and an East German delegation, led by Alfred Kurella.

1999 Zürich discovery

In 1999, the Belgian Guy Droussart discovered several missing prints from Masereel's 1920s graphic novels in the cellar of the Europa Verlag publishing house in Zürich. Not knowing what the initials "FM" stood for, he checked the local library and was stunned to find out that these were woodblocks by Masereel, believed to have been lost. He contacted Masereel's biographer Joris van Parys, who managed to repatriate the woodblocks to Belgium. Among the retrieved treasures were the original woodblocks of 'Débout Les Morts' and '25 Images de la Passion d'un Homme'.

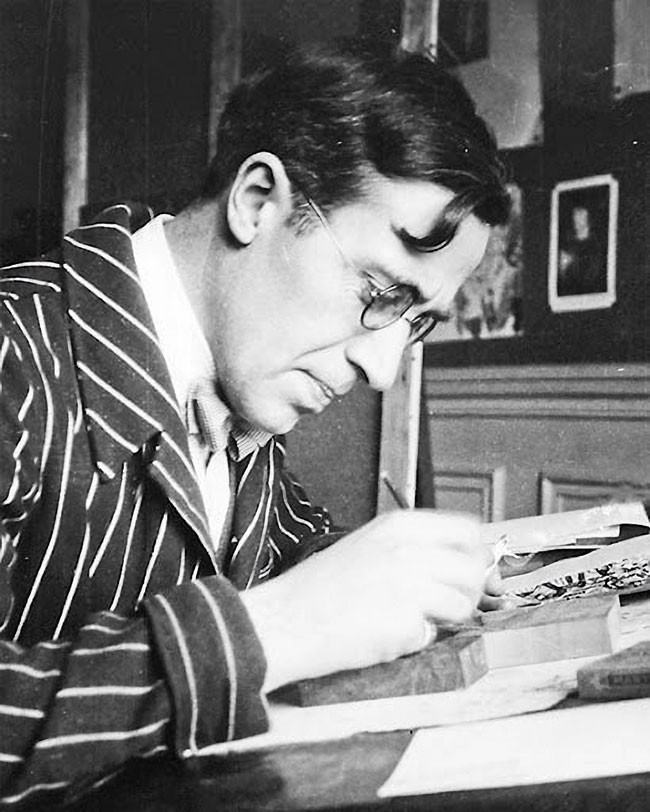

Frans Masereel, photographed in January 1925 by Thea Sternheim, in Paris.

Legacy and influence

Frans Masereel remains a towering figure in the field of woodcut engraving. His work acquired many celebrity fans, including novelists Louis Paul Boon (of 'De Kapellekesbaan' and 'Daens' fame), Thomas Mann (of 'The Buddenbrooks' and 'Death in Venice' fame) and Dutch comedian Kees van Kooten. In 1950, when Hollywood actor Gregory Peck was filming in Nice, he took the time to pay Masereel a visit. Belgian prince Karel/Charles also visited Masereel in March 1954 to receive some art lessons. When Masereel turned 75 in 1964, Belgian queen Elisabeth wrote him a congratulatory letter. German politicians (and future chancellors) Helmut Schmidt and Willy Brandt did the same for his 80th birthday in 1969. During the visit of Belgian Prime Minister Leo Tindemans to China (18-26 April 1975), Mao personally asked him how "the great artist Frans Masereel was doing". China was a very isolated country at the time, which explains why Mao wasn't aware that Masereel had already died three years earlier. Tindemans didn't dare to tell him the truth and simply told him Masereel was doing well. Novelist Stefan Zweig (of 'Letter From an Unknown Woman' fame) wrote in 1923: "If everything was destroyed, all books, all monuments, photos and all texts and only Masereel's woodcuts would remain, one could still reconstruct our current world, how we lived around 1920, how we were dressed. The horrible war on the front and the backlands with their hellish machines, and grotesque people, the city with their stock exchange buildings and machines, stations, ships and towers, the fashions and people, the different types and above all the spirit and genius, the hurried tempo of our times, all that would be understandable just and only through his work."

Frans Masereel was an influential artist in many different fields. His memorable depictions of city life, use of imaginative, distorted imagery and powerful humanist messages inspired countless artists. At the same time, his work was so innovative that people weren't always able to pigeonhole him. Particularly his picture novels confused critics and audiences. Since they didn't feature an accompanying text, one couldn't call him a "true" novelist, nor a straightforward book illustrator. Picture stories had existed before, but Masereel went beyond just telling a simple gag, religious morality tale or historical account. He told deeply human stories without penning down a single word, leaving it to his readers to interpret the images. Even as a comic artist, he wasn't always regarded as one, since his stories didn't revolve around "funny characters". As a result, his groundbreaking works were sometimes forgotten or ignored in historical overviews of significant novelists, illustrators and comic artists. Even in the 1920s, Zweig already named Masereel's graphic novels a genre of its own: "Romane ohne Worte" ("Wordless Novels").

All in all, Masereel stands out as an important Belgian comics pioneer. He forms the bridge between the 19th-century and early 20th-century gag comic artists and the more narrative-based artists who emerged during the 1920s. In this field, his most notable predecessors in proto-comic books were only Richard de Querelles' 'Le Déluge à Bruxelles' (1843) and Félicien Rops' 'Mr. Coremans au Tir National' (1861). But while both these artists only released one comic book each, Masereel released several throughout his career, making him the first known Belgian comic artist with a collectable oeuvre. From this perspective, one could consider him the first comic author in his country to release "albums", decades before Belgium launched its actual comic book industry. The only distinction is that Masereel's books weren't part of a character-based series and aimed at mature readers, rather than children.

From the late 19th century until the end of World War I, many comic artists were mostly concerned with gags or humorous stories. Only a few, like Winsor McCay and Lyonel Feininger in the USA, made comics on a more ambitious, dramatic and artistic level. Again, Masereel proved himself a trendsetter. In the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s, many artists, all over the world, all released their own Masereel-esque picture novels, either directly influenced by him or by the many artists who copied him. The novels were notable for aiming at mature readers, covering humanist or socially conscious themes. Among the notable artists were Lynd Ward ('God's Man', 1929, 'Wild Pilgrimage', 1932), Helena Bochoráková-Dittrichová ('Z Mého Destvi', AKA 'Enfance', 1929), Milt Gross ('He Done Her Wrong', 1930), Carl Meffert/Clément Moreau ('Nacht über Deutschland', 1937-1938), Otto Nückel ('Die Schicksal', 1928), Max Ernst ('Une Semaine de Bonté', 1934) and Giacomo Patri ('White Collar', 1940). As such, Masereel is considered one of the forefathers of the modern-day graphic novel.

In Belgium, Frans Masereel influenced François Gianolla, Ever Meulen, François Schuiten, Steve Michiels and Stef Vanstiphout. Benoît Peeters and François Schuiten's comic series 'Les Cités Obscures', in which a strange city is the central character, took some of its inspiration from Frans Masereel's 'La Ville'. As a direct tribute, one street in the city of Urbicande in 'Les Cités Obscures' was named after Masereel. In issue #11 of the Belgian comic news magazine Zandstraal (2011), Greg Shaw drew a comic strip biography about Masereel's life. Belgian comic artist Kim Duchateau paid homage to Masereel's 'Le Baiser' ('The Kiss') with a 2021 reinterpretation, showing love during the COVID-19 pandemic. Among Masereel's followers in France are David B. and Charles Berberian, the latter also wrote the foreword for a 2019 reprint of 'The City'. Artist Guy Nadeau (Golo) also gave Masereel a guest appearance in his graphic novel 'Istrati! L'Écrivain' (2019), about Romainian-French author Panaït Istrati. Masereel additionally found followers in the Czech Republic (Helena Bochoráková-Dittrichová), Germany (Otto Nückel), The Netherlands (Gerda Dendooven, Milan Hulsing), Spain (Lusmore Dauda) and the United Kingdom (Clifford Harper, Aidan Hughes).

In the United States, Masereel inspired Peter Arno, Charles Burns, Eric Drooker, Will Eisner, Frank King, Austin Kleon, Jason Lutes, Art Spiegelman and Lynd Ward. Several of Art Spiegelman's 1970s comics are drawn in a Masereel-esque style, including 'Prisoner on the Hell Planet' (1972), while the stark black-and-white imagery in 'Mon Livre d'Heurs', alongside Lynd Ward's books, inspired the look of Spiegelman's monumental graphic novel 'Maus'. In Jason Lutes' graphic novel 'City of Stones' (2000), he included a scene in which his characters marvel at Masereel's work. In Canada, Masereel had a strong impact on Catherine Doherty and George Alexander Walker. Walker's 'Book of Hours' (2001) was directly inspired by Masereel's graphic novels 'Mon Livre d'Heurs' and 'La Ville', only here focusing on the lives of New Yorkers on the day of the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001. U.S. scriptwriter Julian Voloj and Syrian-French comic artist Hamid Sulaiman adapted Masereel's life in a graphic novel, 'Frans Masereel: 25 Moments de la Vie de l'Artiste' (2022).

Since 1971, Masereel's name lives on in the Flemish cultural non-profit organisation the Masereelfonds and, since 2016, in the Frans Masereel Centrum in Kasterlee, a meeting place for graphic artists, subsidized by the Department of Culture, Youth, Sports and Media of the Flemish government.

In 1995, Joris van Parys released his biography about Frans Masereel, 'Masereel: Een Biografie', published by Houtekiet (Antwerp) and De Prom (Baarn). Martin de Halleux released a monograph, 'L'Empreinte du Monde' (2018), dedicated to Frans Masereel. De Halleux also launched the graphic project '25 Images', in which several artists are challenged to tell a story in 25 images without text, among them Nina Bunjevac, Pinelli and Thomas Ott.

Frans Masereel on wordlessnovels.com

The full 1995 Masereel biography by Joris van Parys (in Dutch)