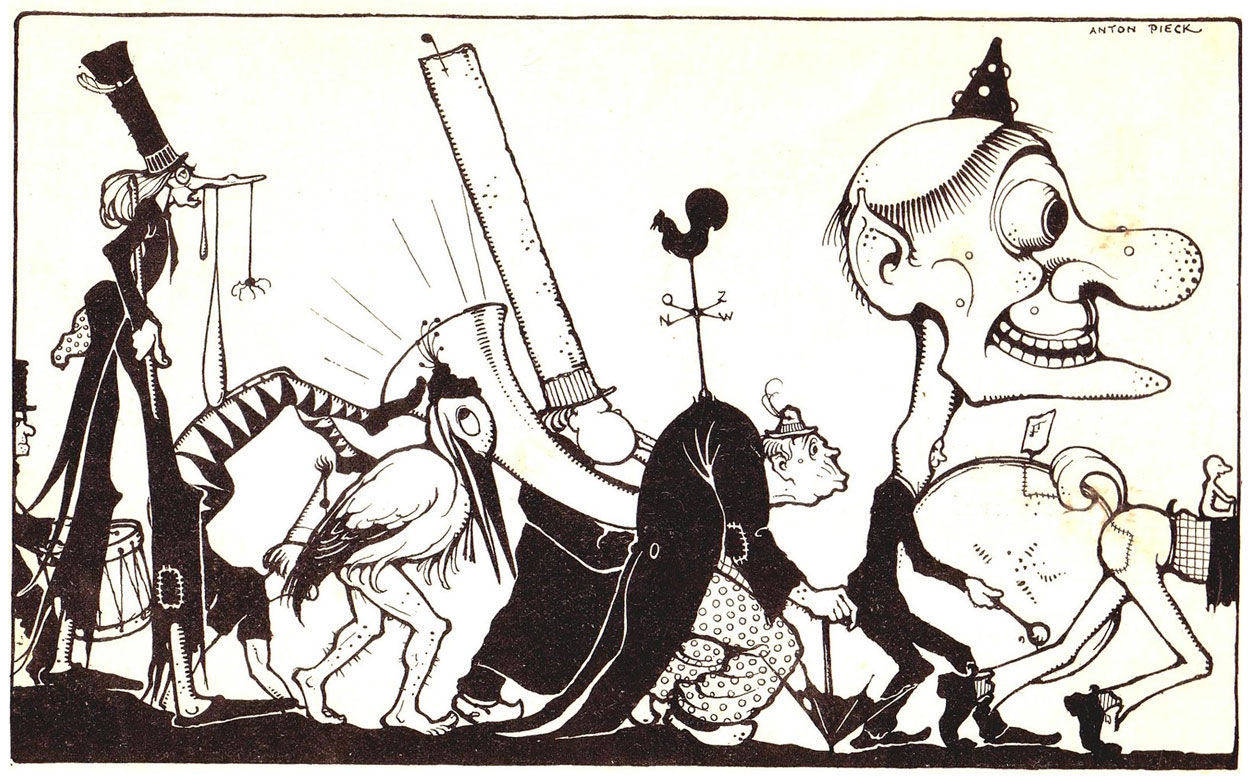

Sequential picture story for a school book.

Anton Pieck was a Dutch illustrator, well-known for his characteristic cozy and nostalgic style. Although he was active throughout most of the 20th century, one couldn't tell from looking at his work, as all of Pieck's paintings and drawings are set in the past. He made countless atmospheric works depicting 19th-century scenes. The Romantic illustrator was well-known for his portrayals of fairy tales, such as his iconic drawings for 'Grimm's Fairy Tales' (1940) and 'Arabian Nights' (1943-1956), which later became the template for the theme park De Efteling. Pieck's illustrations have been popularized by greeting cards, calendars and other merchandising, making him an audience favorite, while others have reviled him for being petty kitsch. Still, friend and foe couldn't deny that he was a highly accomplished draftsman with a unique and instantly recognizable style. In the 1920s, Pieck drew some rare picture stories for the magazine Zonneschijn, with text captions underneath the images. Some of his children's books also occasionally made use of illustrated sequences.

'Aladdin and the Magic Lamp', from 'Arabian Nights'.

Early life

Anton Franciscus Pieck was born in 1895 in the harbor town of Den Helder in the province of North Holland. His father had a small position with the Royal Dutch Marine, and his mother was a housewife. The family was never well off, so young Anton and his twin brother Henri escaped the gloom of poverty by playing outside, reading and drawing. The brothers both studied at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts and the Bik & Vaandrager Drawing Institute in The Hague. Among Anton Pieck's graphic influences were the 19th/20th century city and landscape painters Herman Heuff, Henri Daalhoff, Theo Goedvriend, Adrianus Mioléé, Cornelis Springer, George Hendrik Breitner, Carl Spitzweg, Charles Rochussen, Walter Vaes, Henri De Braeckeleer, W.O.J. Nieuwenkamp and Carl Larsson, as well as the classical painters Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Albrecht Dürer, Rembrandt van Rijn, Johannes Vermeer and Frans Hals and the international graphic artists Hokusai, Gustave Doré, George Cruikshank, Arthur Rackham, Edmond Dulac and Hablot Knight Browne.

During the First World War, the Netherlands remained neutral, but nevertheless many young Dutchmen were mobilized to be on standby in case of a military conflict, and Pieck was one of them. He was promoted to sergeant, but nevertheless spent most of his spare time drawing for his fellow recruits. A 1915 psychological army report described him as "someone who looks more at the past than the future and will therefore never amount to anything." With the realization that they couldn't use him for ordinary military duties, Pieck was sent to The Hague, where he gave drawing lessons to other soldiers. For four evenings a week of two hours each, Pieck could spend all his time doing what he loved best.

Meanwhile, Anton's brother Henri would lead a more adventurous and dangerous life. He became active within the Dutch Communist party, working as a spy for Soviet Russia. During World War II, he fought against the Nazis, was arrested and sent off to concentration camp Buchenwald. He managed to survive and enjoyed a successful post-war career as a children's book illustrator and interior architect, before passing away in 1972. Unlike his brother, Henri was more interested in modern art.

Teaching career

In 1920, Anton Pieck became an art teacher at the Kennemer Lyceum in the coastal town of Bloemendaal. In between lessons, he illustrated diplomas, bulletins, ex-libris, birth cards and other administrational documents for his school. Pieck remained a teacher there until his retirement in 1960. After each school day, he couldn't wait to dash home and sit down behind his drawing table. Although he didn't particularly like his day job, it at least offered him financial stability and the luxury of picking out commissions that pleased him, rather than being forced to work on stuff he disliked.

Pieck's illustrations for the four seasons in the Netherlands.

Style

In the 1920s, Pieck saw his first drawings published. He struck up a friendship with the Flemish writer Felix Timmermans (father of cartoonist GoT), famous for his signature novel 'Pallieter' (1916). Pieck illustrated the 10th reprint of 'Pallieter', released in 1921. To evoke the atmosphere of a Flemish landscape, he travelled to Flanders. Pieck remained an enthusiastic traveller his entire life, visiting England, France, Ireland, Germany, Sweden, Switzerland, Austria, Italy, Poland and Morocco to make sketches. He always regarded Belgium and England as his second mother countries, since their landscapes and architecture weren't as modernized as The Netherlands. Through Timmermans, Pieck was also encouraged to make his artwork more spontaneous, following his own spirit. From 1924 on, he started working in color.

Pieck established a reputation as an atmospheric evoker of anything "ancient". The nostalgic artist had a strong attraction to old-fashioned houses, castles, walls, wells, bridges, market squares, fountains, stairs and roads. Whenever he saw such things in real life, he whipped out his sketch book. Visible decay only made things more authentic. Crumbled stones, rusty doors, crooked constructions and half-deteriorated parchments were all included in his art. In many of his illustrations, he wrote his signature on an unfolded scroll, as his trademark. Or simply put his initials together, to form what resembles a letter 'r'. Pieck was in high demand as an illustrator of historical fiction. He livened up the pages of 19th-century literary classics like Charles Dickens' 'A Christmas Carol' and visualized the lyrics of Franz Schubert's songs, as well as 20th-century novels set in the Victorian or Edwardian era, like Selma Lagerlöf's 'Nils Holgersson' and Margaret Mitchell's 'Gone With The Wind'. Contrary to popular thought, his illustrations for Hildebrand's 19th-century novel 'Camera Obscura' were not made for a book reprint, but a thematic calendar.

Enarmored with the 19th century, countless of Pieck's paintings, drawings, etchings, woodcuts and engravings depict Dickensian scenes. People in high hat or crinoline take coach rides, watch a magic lantern projection or listen to barrel organs or chamber concerts. As Pieck had only lived in the final five years of the 19th century, much of his nostalgia was fed by memorabilia. Still, his work was such a vivid and enthralling evocation that general audiences assumed he was a 19th-century artist who presumably passed away decades ago. In reality, he lived long enough to experience the 1980s.

Pieck was always happy when autumn and winter set in, his favorite time of the year. Many of his most popular illustrations are set during this season, specifically at Sinterklaas (Saint Nicolas) or Epiphany (Three Kings Day). Remarkably enough, he never drew scenes set at Christmas, although his winter-themed illustrations fit this holiday period well. He depicted characters visiting a busy market square in the snow, or enjoying the crackling fireplace in a cozy pub. Horse sleighs pass through the streets, while people go ice skating on the frozen river. Despite the cold weather, communities are busy preparing and anticipating the festivities.

Pieck prepared all his illustrations thoroughly, collecting reference material through countless sketches and photographs. Many of his crowd scenes are filled with scenes-within-scenes. He paid attention to the smallest details, giving them his personal touch, from signs above stores and inns, to sculptures on fountains. His illustrations have such a warm, cosy, idyllic look that viewers can't help but wish they were there in real life. For nostalgic people, they radiate a certain melancholy. To heighten the "ancientness", Pieck used soft greys and yellows.

Pieck was a classic example of a nostalgic person who sometimes felt he was born in the wrong century. In interviews, he expressed being glad of having received a classic, straightforward academic training. In his opinion, aspiring artists could learn far more by simply drawing whatever a teacher puts in front of the classroom than letting them experiment. As such, he had no love for all the great movements of modern 20th-century art, architecture and technology. His prints were done with a Victorian press in his home. It was so heavy that the floor had to receive additional support to avoid it collapsing under its weight. Since the press was difficult to operate, his wife often helped him. Pieck regretted that in the rapidly modernizing 20th century so much nature and picturesque buildings had been torn down. They were replaced with ugly, contemporary architecture, devoid of any character. In his opinion, people in the past spent more time crafting beautiful buildings, since they basically had to live in the vicinity. The arrival of cars and highways made people travel great distances between locations, making it less important that every spot looked nice. Pieck was so old-fashioned that he didn't have a car, radio or a TV. It left him with oceans of time to concentrate on creating art.

In his artwork, Pieck had the opportunity and talent to recreate the worlds he missed so much in real life. He could visualize them according to his own will, leaving out anything he disliked. Yet, despite everything, he wasn't completely out-of-touch or against 20th-century life either. Pieck was a frequent museum visitor and so up to date with most painters of his own era. In interviews, he expressed tremendous respect for the paintings of Norman Rockwell and the animated cartoons of Walt Disney. Though, as critics might notice, both Rockwell and Disney also dwelled in idealized pasts in their art.

Illustration for Zonneschijn (1930).

Fairy tale illustrations

Pieck's ability to mimic days of yesteryear made him a natural for illustrating fantasy stories and fairy tales. During the mid-1920s, he joined the children's magazine Zonneschijn, where his illustrations appeared alongside those of Hans Borrebach, Tjeerd Bottema, Rie Cramer, H. de Hoog, Jan Feith, Jan Kraan, Freddie Langeler, Jan Lutz, Johanna Bernardina Midderigh-Bokhorst, George van Raemdonck, Henri Verstijnen and Jan Wiegman. He made drawings for various children's stories, some published in a text comic format, and also created holiday-themed illustrations for Zonneschijn's annual winter books. Pieck could completely immerse himself into a world of childish wonder, drawing castles, dark woods, giants, gnomes, witches, kings, princes, princesses and dragons. The artist illustrated two books about mythological stories, namely C. van der Horst's 'Het Boek der Helden' (1929) and A. van Hamel's 'De Tuin Der Goden' (1940/1947).

However, his most famous illustration work was done for 'Grimm's Fairy Tales' (1940) and 'Arabian Nights' (1943-1956). Even though he was hardly the first to illustrate these classic stories, Pieck managed to give them a unique feel, as if it was all actually created "once upon a time, a long time ago." For 'Arabian Nights', a monumental work consisting of eight volumes, he spent six weeks in Morocco to sketch local buildings and people in order to evoke a convincing Middle Eastern setting. In 1974, Pieck published a small book named 'Klein Beeldverhaal van 1001 Nacht', presented as a picture story, but in reality just a compilation of previous 'Arabian Nights' illustrations he made, accompanied by quotations from the original tales. The booklet was likely made for people who couldn't afford to buy all eight volumes of the original tales.

Illustration for Grimm's 'The Wishing-Table' ("Tafeltje Dekje, Ezeltje Strekje").

De Efteling

Pieck's illustrations of Grimm's fairy tales directly led to his most famous contribution to Dutch popular culture, theme park De Efteling. In the early 1950s, he was asked to design a fairy tale-themed forest in Kaatsheuvel, a town in the southern province of North Brabant. At first, he declined the offer, since he assumed it would merely be a couple of cardboard sets. When he was guaranteed that actual buildings were to be constructed from his designs, Pieck accepted the commission. Every location in De Efteling received his personal touch. He designed houses and the animatronic inhabitants of the fairy tale forest, alongside gates, water fountains and trash bins. He reminded the architects to build things as crooked as depicted in his designs. Some of the builders were given a little alcohol beforehand, while Pieck once even demanded a freshly built chimney to be knocked a bit more slant. It gave him the nickname "the mild dictator", but all was forgiven when De Efteling opened on 31 May 1952 and became a huge success. It is still the most visited theme park of the Benelux, attracting a lot of Belgian visitors too, since it's not too far away from the Dutch-Belgian border.

Many characters and houses in the Efteling's fairy tale forest were based on Grimm's fairy tales, including the house of Little Red Riding Hood's grandma, Sleeping Beauty's castle, Frau Holle's well and Hansel and Gretel's gingerbread house. Lesser known tales like 'The Six Servants' were also included. The long-necked servant Langnek is still the park's mascot, along with Pardoes the jester, who was designed in 1989 by Henny Knoet. As the park grew, Pieck gave other fairy tales a spot too, some by authors he never illustrated, like Charles Perrault ('Hop-o'-My-Thumb'), Hans Christian Andersen ('The Red Shoes') and the Belgian queen Fabiola ('The Indian Waterlilies'). When singer and children's writer Martine Bijl wrote the fairy tale 'De Tuinman en de Fakir' for De Efteling, it was also included in the park. More general fantastical items like gnomes, trolls, a dragon and a haunted castle were added as well.

An often repeated story claims that Walt Disney once visited De Efteling to seek out inspiration for his own theme park Disneyland (1955), but this has been debunked as an urban legend. Pieck himself, however, visited De Efteling on a weekly basis. One of its squares has been named after him and harbours a carousel he used to ride on in his youth. The park owners were able to buy the original ride, restore it and put it in the park. Pieck also designed various merchandising items for De Efteling, including books and cards.

Autotron

In 1972, another attraction designed by Anton Pieck opened its doors in North Brabant: the Autotron in the town of Drunen. The place was created to exhibit antique cars in an aesthetically fitting location. Even though he didn't like cars, Pieck still enjoyed designing the entire building in his signature style. In 1987, the Autotron was relocated to Rosmalen, where it closed its doors in 2003. The original building designed by Anton Pieck is nowadays the cultural center known as De Voorste Venne.

Cover illustration for 'Het Efteling Sprookjesboek' (1955).

Popularity

As early as 1913, Anton Pieck's drawings were used for calendars. From 1938 on, he started designing New Year's cards for the children's benefit organization Voor Het Kind. They were a success in his home country and also huge bestsellers in the United States. Between 1947 and 1952, he designed calendars for the bakery product company Calvé. When his clients received his drawings, they deliberately printed them in a larger format, so people could see the details better. By appearing on calendars, greeting cards, mugs, agendas, stationery, puzzles, stamps and novels, Pieck became a household name in the Netherlands, which increased once the theme park De Efteling was established. Here fans could actually experience his cozy, nostalgic world in real life. His style became so recognizable that it spawned an eponym: "Pieckian" of "Pieck-esque". The artist recalled that he was once painting outside in Amsterdam when a young artist looked over his shoulder and told him: "That's beautiful, but you're going to get in trouble." When Pieck asked him why, the artist felt indignant and replied: "Don't you see? It's a pure imitation of Anton Pieck!"

Right from the start, Pieck was extraordinarily popular with general audiences. During his lifetime, he understandably appealed to old folks who actually experienced the 19th century firsthand. But even as these generations died off, Pieck remained beloved with their children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren. His Victorian Era-themed illustrations capture "the good old days". In the eyes of his many admirers, he visualized it better than any photograph. Or, at least, how they imagine it to have been. Pieck's old-fashioned art is, contradictively enough, timeless. As our present-day society keeps modernizing, the world depicted in Pieck's illustrations only becomes more distant, melancholic, even intriguingly strange. A seemingly simpler time, before all the technological, noisy and shallow distractions of the modern world existed.

Pieck lived long enough to enjoy ongoing media attention and public interest for his illustrations, which were frequently compiled into thematic books. In 1984, the Anton Pieck Museum opened its doors in Hattem, where many of his paintings, etchings, lithographs, press and drawing table are nowadays exhibited.

Artwork by Anton Pieck. The mother and her child in the left corner are portraits of Pieck's own mother and himself as a boy.

Criticism

Among art critics and sophisticates, Pieck has always been the subject of scorn and derision. As an illustrator, he was already out of league with "true art". On top of that, he was never an innovator. All his illustrations share the same visual style. He was an unapologetic Romanticist when this was considered to be highly square and conventional. Pieck's graphic universe is a dreamy, safe and chaste world, devoid of any controversy. Human misery, sex and violence are absent. Even his portrayals of 19th-century society, which are grounded in reality, are still rose-colored depictions of the historical past. In Pieck's work, it's the era of high wheel bicycles, carol singers, photographers and classic novels, not of child labor, black slavery, factory smog or exploitation of common workers. Even when poverty or colonialism are addressed, it is presented matter-of-factly. This also tied in with Pieck's personality. Politics didn't interest him. He didn't even read papers and received all his info about current events from casual conversations with other people. Most of the time, he just retreated into his own little secluded melancholic dream world on paper.

The Assendelfstraat in The Hague.

Also, Pieck lacked any artistic pretense. None of his artwork expresses autobiographical themes, socially conscious messages or personal drama. He was content just to be a fine draftsman. Likewise, Pieck saw no qualms in the fact that his work was "cheapened" by being mass-produced on calendars and holiday cards. In the eyes of his critics, he is therefore a poster child for petty, corny and sentimental kitsch, with De Efteling theme park as a triumph of mediocrity. In 2004, during the elections for "The Greatest Dutchman" on NOS TV, the magazine HP/De Tijd organized a parody of this event, "The Worst Dutchman". Pieck was one of their 100 nominees, though he was never voted into the final list. Interestingly enough, in "The Greatest Dutchman", he was voted to the 81th place.

However, Pieck didn't care much what critics said. Unlike what one might expect, he didn't earn all that much from all the advertising based on his artwork. He rejected many business deals, merely because the necessary paperwork would leave him with less time to draw and paint. He didn't want to be rich, being perfectly satisfied to have plain financial stability. Pieck also wasn't oblivious to the less pleasant aspects of the past: he vividly recalled that, as a boy in the 1900s, many people in his neighborhood died from a tuberculosis epidemic. Pieck also pointed out that many artists from previous centuries whom we nowadays regard as grandmasters just wanted to create fine work, unaware that it would once be judged as "art". He too rejected the epithet "artist" and was simply dedicated to the activity he enjoyed most: drawing. Even his harshest detractors couldn't deny that he was an accomplished, gifted artist.

Some of his artworks even have historical importance, as Pieck sketched many streets, villages, cities and landscapes before modernization changed them forever. And while his work lacked socially conscious messages, Pieck did put his talent to good use during World War II. He helped out the Resistance by counterfeiting official documents to mislead the Nazi authorities. He did his job so well that many were fooled and those who survived the war even had trouble convincing officials that these papers were faked. Pieck also helped Jewish refugees hide in his home. He had the audacity to refuse joining the Nazi-controlled Kulturkammer, even though artists were forced to become a member of this art group.

Recognition

After World War II, Pieck was decorated as a Knight (1960) and an Officer (1980) in the Order of Orange-Nassau for his brave and noble accomplishments for the Dutch resistance. The veteran received other honors too. In 1977, he was asked to design an official stamp for the Dutch postal services. In 1983, a bronze statue of his head was unveiled in the town of Overveen and a year later he received his own museum in the village of Hattem. Pieck recalled that his grandson made the funny observation: "Isn't it strange that only grandpa's head is famous?".

Carnival scene illustration for the magazine Zonneschijn (1926).

Legacy and influence

Anton Pieck enjoyed a long and productive career, literally working until the day he died, in 1987. On his table, people found an unfinished illustration he had been crafting the night before. Posthumously, Pieck's illustrations have remained beloved with audiences in reprints, while the Efteling theme park still attracts thousands of visitors a day. In Zaventem, Belgium, a restaurant has been named after him.

Among Anton Pieck's notable admirers have been the novelist Felix Timmermans, artists Willy Vandersteen, Jacques Laudy, Dick Bruna, Adolf Melchior, Marten Toonder, Lies Veenhoven and British illustrator Pat Cooke. In 1973, the Dutch light poet Drs. P wrote the poetic song 'Winterdorp' (1973), in which he pays homage to Pieck's art. Seeing that Drs. P was quite old-fashioned himself, the admiration was understandable. On the occasion of Pieck's passing, Belgian poets Bert Peleman and Anton van Wilderode both wrote an "in memoriam" to him. Last but not least, Anton Pieck had a cameo in Willy Vandersteen's comic series 'Suske en Wiske': in the 1982 album 'De Belhamel Bende' he is pictured behind his easel, drawn by Paul Geerts.

Anton Pieck with Willy Vandersteen, looking at the Suske & Wiske album 'De Efteling-Elfjes'.