George Van Raemdonck, sometimes spelled as "Georges", was a Belgian illustrator, painter, political cartoonist, book cover designer and comic creator. He is best remembered as the co-creator of 'Bulletje en Boonestaak' (1922-1937), a text comic scripted by the famed Dutch writer A. M. de Jong. Between the two world wars, 'Bulletje en Boonestaak' was one of the most popular Dutch-language comics, starring two young rascals who enjoy exciting adventures at sea. The stories featured social commentary from the authors' socialist viewpoints, and were notorious for their subversive comedy and imagery. Moral guardians called the series "obscene", but couldn't prevent the feature from having success. The first Dutch-language newspaper comic with a notable durability and impact, 'Bulletje en Boonestaak' also spawned a collectable comic book series and was the first Dutch comic to be translated into German and French. Historians generally consider 'Bulletje en Boonestaak' the starting point of Dutch comics, and Van Raemdonck as the first significant Flemish and Dutch comic artist. His collaboration with novelist A. M. de Jong is also the first example of a Belgian-Dutch comic creator team-up. Besides his work on other comics, Van Raemdonck is also recognized as a powerful political cartoonist, contributing regularly to the socialist magazine De Notenkraker. His sharp cartoons against war, Fascism and Nazism are still frequently reprinted. In his home country of Belgium, Van Raemdonck was largely known as a portrait painter.

Early life and career

George Van Raemdonck was born in 1888 in Antwerp, Flanders. His father was a Dutch-speaking pharmacist and part-time painter. His French mother died when the boy was young, and George was largely raised by his grandmother. Van Raemdonck was a creative soul, showing a gift for both painting and music. He inherited his gift for drawing from his father, Joseph van Raemdonck. One of Van Raemdonck's 17th-century ancestors was an engraver in the days of Peter Paul Rubens. At age fifteen, George van Raemdonck enrolled at Antwerp's Royal Academy of Fine Arts, where he studied during 1903 to 1908. He continued his education at the Higher Institute of Fine Arts between 1908 and 1914, where the painter Franz Courtens taught him the finer points of landscape painting. In 1909, he moved to Zwijndrecht, a town in the periphery of Antwerp, where he lived the bohemian life. In 1913, Van Raemdonck's talent was recognized by the Royal Academy with the Nicaise De Keyserprijs. In addition to fine arts, Van Raemdonck also studied violin at the Conservatory. As a student, Van Raemdonck made illustrations for the weekly magazine Lange Wapper and several folksy novels.

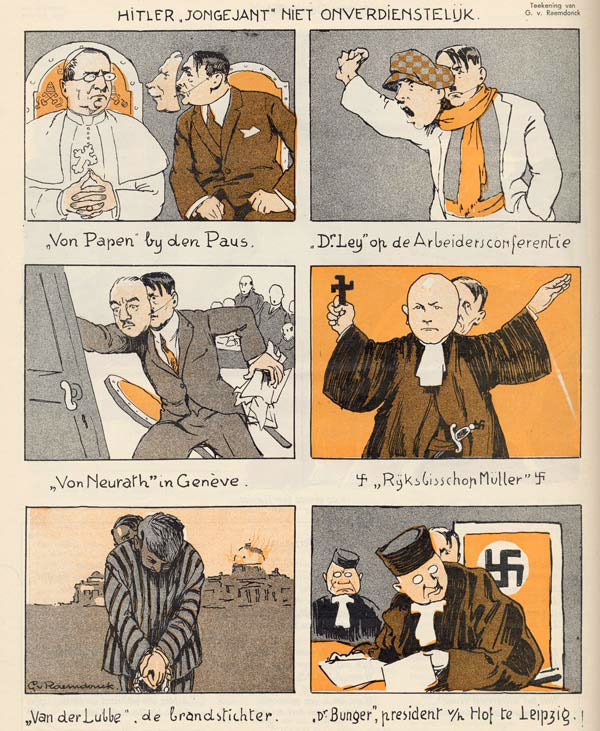

Satirical picture story from 1933 spoofing Adolf Hitler (De Notenkraker, 1933). Hitler is depicted as the man holding the strings behind several people who claim to operate alone, namely German vice-chancellor Franz von Papen, German Labor Front party leader Robert Ley, Foreign Minister Konstantin von Neurath, National Bishop Ludwig Müller, pyromaniac Marinus van der Lubbe (who set the Reichstag on fire in 1933, which many people believe was actually instigated by the Nazis as an excuse to start persecutions) and Wilhelm Bünger, judge of the Supreme Court.

Political cartoons

Van Raemdonck's life and career took a drastic turn when the First World War broke out. Although Belgium tried to remain neutral, German troops conquered it in 1914. George Van Raemdonck and his Dutch wife Adrienne Denissen found refuge in The Netherlands, which managed to maintain its neutrality. They first settled in Heemstede, then in 1918 moved to Halsteren, a village not far from Bergen op Zoom in the southern province North Brabant. Van Raemdonck spent fourteen years in the Netherlands, from 1914 to 1928. He found a steady job as illustrator and cartoonist for De Amsterdammer (nowadays De Groene Amsterdammer), a magazine devoted to trade, industry and art. His first cartoon was printed in the 6 December 1914 issue. Among his colleagues were cartoonists Johan Braakensiek, Wam Heskes, Felix Hess, Leendert Jordaan, Bernard van Vlijmen and Henri Verstijnen.

Drawing about the Turkish-Armenian War, made for De Amsterdammer. A German and a Russian ask a Turk whether he's not ashamed of killing Armenians? He answers: "Me? Ashamed?... I act based on European example."

Even though he was safe from the war atrocities in Belgium, Van Raemdonck was understandably very concerned about his home country. He drew several powerful cartoons about "The Great War". Some depicted the latest weapons, such as the German Big Bertha cannon, others featured war crimes like the Turkish genocide on Armenian citizens. He also drew the "Wire of Death'' at the Belgian-Dutch border. This was a wire fence intended to keep illegal immigrants and war refugees from fleeing to The Netherlands. Many people who tried to cross the border got shot or stuck on the wire. Van Raemdonck's most memorable World War I cartoons were compiled in the book 'De Eerste Kartoens van George van Raemdonck' (Boechout Belgium, I.H.A., Het Speelhof, 2014).

Drawing of A.M. de Jong with the characters Bulletje and Boonestaak by George van Raemdonck.

A.M. de Jong

In 1917, George Van Raemdonck struck up a close friendship with the Dutchman A. M. de Jong (1888-1943), a former teacher and journalist who was drafted in the Dutch army during World War I. Although The Netherlands were neutral, the army was on stand-by in case of a sudden military invasion. A firm socialist, De Jong strongly criticized the military institution in his book 'Notities Van Een Landstormman' (“Notes From A Landsturm man”, 1917), leading to his official removal from active duty. An amateur artist himself, De Jong was impressed with Van Raemdonck's anti-war cartoons. Their first collaboration was De Jong's children's novel, 'De Vacantiedagen' (“The Holidays”, Cenijn en Van Strien, 1917), for which Van Raemdonck made the illustrations. Their correspondence was in French; Van Raemdonck was from Antwerp's upper middle class, where French was the common language, and De Jong wanted to improve his foreign language skills. Van Raemdonck and De Jong also shared a common interest in the ideals of the labor movement. They regularly organized meetings to empower workers in demanding their rights. In the 1920s, Van Raemdonck illustrated propaganda posters for the Belgian Socialist Party, AKA the Belgische Werkliedenpartij, making him the first Belgian comic artist in history to make advertisements for a political party.

Covers for De Notenkraker from 1933. "Imperialism shows its true face" (18 February 1933) and Adolf Hitler being pulled into a bath by "Reason" (5 August 1933).

De Notenkraker

In 1919, A.M. De Jong was appointed editor of Internal Affairs at Het Volk, the daily evening newspaper of the Social Democratic Workers Party. That same year, he also became the editor of De Notenkraker, the leading socialist satirical weekly known for its political cartoons. Most likely instigated by De Jong, Van Raemdonck left De Amsterdammer in 1920 to join De Notenkraker as well. Van Raemdonck continued his activities as a political cartoonist until the magazine's final issue on 11 July 1936, making many timeless cartoons, characterized by their sharpness, honesty and engagement. Often self-explanatory, the drawings showcased the artist's contempt for and worries about Fascism, Nazism, war, poverty, unemployment, lack of rights and inhumanity. Several of his cartoons criticized Hitler and Mussolini. Some notably used a comic strip format. Among De Notenkraker's other graphic contributors at the time were Tjeerd Bottema, Albert Funke Küpper, Albert Hahn, Jr., Leendert Jordaan and Jan Rot.

Bulletje and Boonestaak, reprimanded by their fathers.

Bulletje en Boonestaak

In 1922, A. M. de Jong and George Van Raemdonck teamed up again to create a children's comic for Het Volk. On 2 May 1922, the first episode of 'De Wereldreis van Bulletje en Boonestaak' ("The World Voyage of Bulletje and Boonestaak") appeared in print. Like most European newspaper strips at the time, it was a text comic, with text captions underneath the images. Unlike U.S. daily strips, which offered four or five panels, each 'Bulletje en Boonestaak' episode was two panels long. Underneath the first episode, the editor added the text "Uitknippen en bewaren" ("Cut out and keep"), almost as if he was aware how successful and historically important this series would become.

The main heroes are two boys. Bulletje is short and somewhat chubby, Boonestaak is tall and wears a checkered cap. His name literally means "beanstalk" (and in later reprints it was changed according to the new Dutch spelling into "Bonestaak"). Bulletje and Boonestaak are best friends, but still squabble and fight constantly. In their very first adventure, the kids run away from home as stowaways on the Herkules, the ship where Bulletje's father is a coxswain and Boonestaak's dad a sea captain. When they are discovered, they are allowed to stay on board and accompany the crew on the open seas, visiting many countries. They set foot in London, New York City, California, Brazil and China. The boys meet real-life celebrities, like Hollywood western star Tom Mix, as well as famous fictional characters, including Sinbad the Sailor. The authors Van Raemdonck and De Jong also gave themselves occasional cameos.

Ouwe Hein as "king of the savages" in 'Ouwe Hein in Eldorado'.

Another breakthrough character in the comic was the old sailor Ouwe Hein. As the series progressed, his importance grew, as he often tells the boys spellbinding stories about his previous adventures at sea. His anecdotes are so unbelievable that they come across as tall tales, or better said, typical "sailor stories", but Bulletje and Boonestaak still find them very entertaining. The character of Ouwe Hein allowed De Jong and Van Raemdonck to sometimes move away from the general narrative and tell different kinds of stories, which kept the series fresh and unpredictable.

Within a couple of years, 'Bulletje en Boonestaak' had a tremendous following among Het Volk's readership. After a first series of 2600 strips concluded on 2 February 1931, the newspaper considered dropping 'Bulletje en Boonestaak' for financial reasons. Hundreds of readers protested against this decision and demanded the feature's return. Even Willem Drees Jr., the nine-year old son of politician and future Dutch Prime Minister Willem Drees, strongly objected in a letter (in adulthood, Drees Jr. would write the foreword for the reprint editions of 'Bulletje en Boonestaak'). After nine months of absence, on 2 November, Bulletje and Boonestaak made a triumphant return to the papers. The comic kept running for another six years, with the 4,428th episode closing the series on 17 November 1937. However, the ending was very abrupt. The two boys were still at sea and never returned to The Netherlands. But in the final panel, De Jong and Van Raemdonck did appear to say their loyal readers goodbye.

Colorized 'Bulletje & Bonenstaak' strip from VARA-Gids.

Success and historical importance

'Bulletje en Boonestaak' have remained a landmark in Dutch comics. The rascals' exciting adventures at sea and in exotic countries were vividly visualized by Van Raemdonck. In a time when children had little media to provide them with an outside view of the world, the comic offered them a glimpse of what they were missing. But adults enjoyed the comic just as much as the kids did. In a few years' time, newspaper Het Volk attracted more readers and subscribers. On 2 October 1929, 'Bulletje en Boonestaak' also appeared in another social-democratic newspaper, Voorwaarts. Between 2 and 17 November 1931, their new adventures appeared simultaneously in both Het Volk and Voorwaarts.

'Bulletje en Boonestaak' is the first example of an ongoing Dutch comic series with recurring characters. Previous homegrown comics in Dutch media were mostly one-shot stories and its characters rarely reused in new narratives, for instance the boys Yoebje and Achmed from Henk Backer's newspaper strip 'Nieuwe Oostersche Sprookjes' (1921). The one arguable Dutch predecessor was 'Uit Het Kladschrift van Jantje' (“From Jantje’s Scrapbook”, 1916-1936) by Felix Hess in De Groene Amsterdammer magazine. This feature presented stories written and drawn from the perspective of a child, yet it was more comparable to an illustrated column with the character Jantje "drawing" his observations, rather than having an active part in them. 'Bulletje en Boonestaak', on the other hand, was a genuine adventure comic built around the personalities of two title characters. Contrary to 'Uit Het Kladschrift van Jantje', the episodes weren't self-contained, but part of an ongoing narrative. 'Bulletje en Boonestaak' was also collectable in book format, much like a modern-day comic book series. From 1923 onwards, several 'Bulletje en Boonestaak' stories became available in landscape format books by the publisher Ontwikkeling in Amsterdam. In 1926, the publisher also began releasing hardcover portrait format books. In the 1930s, the series was reprinted as pocket editions by De Arbeiderspers. After World War II, the landscape format returned in new Arbeiderspers editions, while in the 1960s and 1970s, the stories were even restyled into balloon comics, with a different lay-out. In later years, the 'Bulletje en Boonestaak' comics were reprinted in Het Vrije Volk (1947-1951) and - in color - in the radio guide VARA-Gids (1958-1965). Between 2001 and 2012, the publishing company Boumaar released the latest book editions of the series.

Post-war 'Bulletje en Bonestaak' reprint series by De Arbeiderspers.

'Uit Het Kladschrift van Jantje' ran for 20 years straight, being the longest-running Dutch comic at the time. 'Bulletje en Boonestaak', with a 15-year run, was for a while the second longest-running Dutch comic series, until both comics were surpassed in 1951 by Frans Piët's 'Sjors' (en Sjimmie)'. And although 'Uit Het Kladschrift van Jantje' was also the first Dutch comic to be translated, (into German in 1924), 'Bulletje en Boonestaak' enjoyed more foreign exposure. In the 1920s, the comic appeared in Belgium in the Flemish newspaper De Volksgazet. In 1924 'Bulletje en Boonestaak' was translated into German ('Dickerle und Bohnenstange') and in 1926 in French ('Fil-de-Fer et Boule-de-Gomme'). In 1947, De Jong and Van Raemdonck's comic was adapted into a theatrical play. In the 1995-1996 theater season, 'De Wereldreis van Bulletje en Bonestaak' was performed by the children of the Jeugdtheater Hofplein in Rotterdam, under direction of Louis Lemaire.

Although 'Bulletje en Boonestaak' followed a long tradition of comics about naughty children, heralded in by Wilhelm Busch's 'Max und Moritz' (1866) and cemented by Rudolph Dirks' 'Katzenjammer Kids' (1897-2006), it was still very original and typically Dutch. Since The Netherlands are a sea-faring nation, stories about sailors have always been popular. 'Bulletje en Boonestaak' was the first Dutch naval comic, and paved the way for future successful series, such as Pieter J. Kuhn's 'Kapitein Rob' (1945-1966), Marten Toonder's 'Kappie' (1945-1972) and many more.

The collaboration between the Dutch-born writer A.M. de Jong and the Flemish artist George Van Raemdonck also marked the first Dutch-Flemish collaboration in comic history. It wasn't until the 21st century before more international collaborations between Dutch-language authors came about, for instance the team-ups of Willy Linthout & Erik Wielaert ('Het Laatste Station', 2007-2008), Hanco Kolk & Kim Duchateau ('De Man van Nu', 2016) and Martin Lodewijk & Claus D. Scholz ('De Rode Ridder', 2004-2012).

Bulletje and Boonestaak get seasick.

Style, appeal and controversy

'Bulletje en Boonestaak' owed a large part of its appeal to the fact that the two boy characters were by far not clean-cut, well-behaved children. Already in their first story, they skip school to travel along on their dads' ship. The boys often argue with other kids, call them names and get into fights. Sometimes they beat up each other as well. In perhaps Bulletje and Boonestaak's most questionable and outrageous action, the boys visit the headquarters of the London Evening News, where they meet Harry Folkard's comic characters Billy Bimbo and Peter Porker. At the time, these English characters were very popular in Dutch translation, running in the newspaper De Telegraaf under the translated names 'Jopie Slim en Dikkie Bigmans'. But their crossover isn't a happy occasion. Bulletje and Boonestaak decide to beat up the little gnome and his pig friend, because "these two English monstrosities had bored Dutch children quite enough with their whining." Boonestaak refers to Jopie Slim as "Jopie Slijm" ("slim" means "smart", "slijm" is the Dutch word for "slime"). This harsh cameo was more than a simple pop cultural reference. Het Volk and De Telegraaf were rival newspapers, also in ideological terms. While Het Volk was socialist, De Telegraaf was a right-wing conservative newspaper. In interviews, writer A. M. de Jong explained that coming up with some counterweight to the "insipid" adventures of 'Jopie Slim en Dikkie Bigmans' was one of the main reasons for starting 'Bulletje en Boonestaak' in the first place.

Bulletje and Boonestaak harassing Jopie Slim and Dikkie Bigmans. While the English bobby does break up the fight, he amusingly agrees afterwards that the disgustingly cute Jopie and Dikkie did indeed "deserve a good thrashing". The bobby even encourages them to continue, because, as far as he is concerned "Jopie and Dikkie can never be beaten up hard enough."

Indeed, 'Bulletje en Boonestaak' was a very subversive comic for the times. Several scenes taunted censors. In one narrative, for instance, the boys get seasick and throw up. In most illustrated stories at the time such action wouldn't be visualized, or at least merely suggested by showing characters discretely from the back. Van Raemdonck, however, shows their vomiting faces in full, disgusting view. Bulletje and Boonestaak are sometimes shown in the nude too, with their genitals exposed in a matter-of-fact fashion. Other imagery in the series could be quite gruesome and violent. In one scene, Bulletje imagines himself being roasted above a fire by cannibals. When his father tells him a keelhauled sailor once had his legs bit off by a shark, this is shown in bloody detail. Another narrative features a surreal head transplant. In one of his tall tales, Ouwe Hein tells how his ship was once attacked by buccaneers. To defend himself, Hein takes a large knife and engages in a fight with the robber chieftain, who is armed with a sword. They strike each other at the same moment, after which heads fly through the air and coincidentally change places accurately. Thanks to the tropical heat, the heads quickly become attached to their new bodies. The men return home, but their wives do not want a man with the wrong body. A genius English doctor is willing to risk a head transplant. Van Raemdonck draws the man working with saws and soldering irons to perform the only head transplant in history so far.

With its scenes of vomiting, vulgar language, nudity and gruesome violence, De Jong and Van Raemdonck's comic was ahead of its time. Such "obscene imagery" wouldn't be seen in Dutch mainstream comics until three decades later, in the 1960s. Moral guardians complained and wrote angry letters to the paper, inadvertently giving the series extra publicity. But 'Bulletje en Boonestaak' was more than pure anarchy. De Jong and Van Raemdonck were socially conscious authors who tried to educate young readers. The characters often travel the world, meeting different people who, in the end, turn out to be not so different after all.

Bulletje and Boonestaak celebrate International Workers' Day in De Notenkraker on 1 May 1922.

De Jong included anti-colonialist and anti-imperialist themes in his narratives, showing respect and compassion for people of different countries and races. Exploitation of poor people is criticized, and war is condemned. In one touching scene, Bulletje and Boonestaak notice a mutilated World War I veteran begging in the streets. They give him some money, while the narrator mentions how sad it is that this once decorated military hero now has to scrape by for a living. True to their idealistic background, the authors used 'Bulletje en Boonestaak' to spread the socialist ideals. In addition to the daily strips, between May 1922 and March 1928, Van Raemdonck also featured the two characters in at least eleven of his political drawings for De Notenkraker, making them icons of the working class.

Censored nudity in 'Bulletje & Boonestaak'.

Past reprint editions of 'Bulletje en Boonestaak' often censored certain scenes. The boys giving a mutilated soldier money was cut in the 1928-1931 book edition by Van Nelle. A robber disguised as a vicar, Zwarte Jack, was suddenly rewritten to become a sheriff. When the stories were reprinted again in 1949-1959, censorship became even more rampant. After World War II, comics were seen in a negative light by parents, teachers and other moral guardians. Particularly in The Netherlands anything that wasn't family friendly had to be edited or cut. Scenes in which the boys were nude were altered. Their exposed genitals were covered with convenient black swimming shorts. Once again, the mutilated soldier scene was removed.

'Appelsnoet en Goudbaard' (Blue Band magazine, 1926).

Other comics in the 1920s and 1930s

During the 1920s and 1930s, Van Raemdonck was also a regular in the children's magazine Zonneschijn, sharing pages with illustrators like Hans Borrebach, Tjeerd Bottema, Rie Cramer, H. de Hoog, Jan Feith, Jan Kraan, Freddie Langeler, Jan Lutz, Johanna Bernardina Midderigh-Bokhorst, Anton Pieck, Henri Verstijnen and Jan Wiegman. Between 1925 and 1927, Van Raemdonck and De Jong created another text comic together, 'Appelsnoet en Goudbaard' (1925-1927), which ran in Blue Band magazine, a publication issued by the margarine brand Blue Band. Appelsnoet and Goudbaard are two bearded gnomes, who get involved in strange fantasy adventures. Some of the imagery is remarkably frightening, considering this comic aimed at a family audience. In 1963, 'Appelsnoet en Goudbaard' was collected in book format by BK Boekenkring and NIB-Zeist.

Van Raemdonck also created the funny animal comic 'De Stoute Streken van Boefie en Foefie, de Rattenbengels' (“The Naughty Pranks of Boofie and Foofy, the Rat Scoundrels”, 1931), which appeared in regional newspapers like Utrechts Nieuwsblad from 29 October to 14 December 1931. It featured two naughty little rats.

'Boefie en Foefie' (Utrechts Nieuwsblad, 31 October 1931).

Book illustrations

On 12 November 1928, George Van Raemdonck moved back to Belgium, first returning to Zwijndrecht and then settling successively in Antwerp, Kapellen and Edegem. He continued to draw new episodes of 'Bulletje en Boonestaak' and do other graphic work for Dutch papers and magazines. He illustrated several novels by A.M. de Jong, who in the 1920s grew more famous as a children's novelist. His best known novels were 'Merijntje Gijzen' (1925) – illustrated by Van Raemdonck - and 'Frank van Wezels Roemruchte Jaren' (1928). When De Jong translated Adrien Zograffi's book 'Panait Istrati' (Querido, 1933), Van Raemdonck also provided new artwork. Even after 'Bulletje en Boonestaak' came to an end, Van Raemdonck and De Jong stayed in touch. A strong fighter for socialist ideals throughout the rest of his life, De Jong was arrested by the Nazis during World War II, but released shortly afterwards because of his bad health. On 18 October 1943, A. M. De Jong was executed by the SS as retribution for the murder of a couple of NSB members by resistance members. In reality, he had nothing to with these murders, but he was shot, along with other random people, to set an example.

Apart from De Jong, George Van Raemdonck illustrated books by several other Dutch and Flemish authors, livening up the pages of over 81 titles. He, for instance, collaborated with novelist A.D. Hildebrand, nowadays best known as the creator of 'Bolke de Beer'. He illustrated his books 'Belfloor en Bonnevue, De Twee Goede Reuzen' (1938) and its sequel 'Nieuwe Avonturen van Belfloor en Bonnevenue' (1941), both published by De Arbeiderspers. Van Raemdonck frequently worked together with Flemish playwright and novelist Anton Van De Velde, illustrating his works 'Prins Olik en Sire Bietekwiet' (Davidsfonds, 1932), 'Doctor Slim en de Microben' (Leeslust, 1932), 'Nele Van Ingedal' (Vlaamsche Boekcentrale, 1944) and 'Bukske en de Mol' (H. Proost, 1945). Van Raemdonck's art also adorned the covers and pages of Herman Heijermans' 'Droomkoninkje' (1924), F.J. Kemp's 'Janske, Een Verhaal voor Groote en Kleine Menschen' (Turnhout, 1930s), Lode Conté's 'De Geleerde Bollen' (H. Proost, 1940), Leen Van Marcke's 'Adieu Het Lichte Huis' and Cor Ria Leeman's 'De Lachende Civa' (H. Proost, 1950). Van Raemdonck also livened up several musical sheet books, among them 'Zingen met Nonkel Bob' (1960), a collection of children's songs featured prominently in the TV show 'TV Ohee Club', starring Bob Davidse, AKA "Nonkel Bob".

'Marino', one of the final comic strips by George Van Raemdonck, made for CVB Magazine, 1958.

Post-war comics

After World War II, Van Raemdonck remained active as a painter. With writer Jef Van Droogenbroeck (who used the pseudonym Lode Roelandt), he created text comic adaptations of Franz Schreker's opera 'Der Schmied von Gent' (known in Dutch as 'Smidje Smee', 1949-1950) and Charles de Coster's classic novel 'Tijl Uilenspiegel' (1951-1953), published in the newspaper Vooruit. The latter was reprinted in the same paper between 1962 and 1965 and also made available as a landscape format book. Van Raemdonck and Roelandt also made a text comic based on Daniel Defoe's 'Robinson Crusoë', which ran in the weekly magazine of the socialist union ABVV and its French-language counterpart FGTB. Their comics were also published in book format by De Vlam, a publisher from Ghent. Another Roelandt and Van Raemdonck comic, 'De Schepping', was never finished due to Van Raemdonck's illness. One of his final comics was 'Marino', which appeared in CVB P.V.B.A. Magazine, a 1958 publication from the advertising industry. The story revolved around a medieval king named Marino I and was presented bilingually, with Dutch and French text captions underneath each image.

Recognition

Very early in his painting career, George Van Raemdonck was honored with the Nicaise de Keyserprijs (1913), awarded by the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp. Later in life, he was knighted twice in Belgium, in the Order of Leopold II and in the Order of the Crown. He was also awarded with a gold medal in the Order of Grand Duke Gediminas.

Final years and death

In 1947, Van Raemdonck moved to Boechout, outside Antwerp, where he lived until the end of his life. In 1958, Van Raemdonck drew caricatures for the pigeon fancier magazine Duifke Lacht, which also appeared in French under the name Pigeon Rit. Van Raemdonck's sculpted portrait of composer Jef Van Hoof is part of the memorial for the composer, located at the Jef Van Hoofplein in Boechout. As a regular client in the local bar Sportbors, Van Raemdonck often drew caricatures of local citizens on beer coasters, which were then exhibited on the bar walls. In 2009, these drawings were compiled in a book, 'Boechoutse Koppen' (Zeppo, 2009). George Van Raemdonck passed away in 1966 in Boechout. He was 78 years old.

Drawing of a cat, unknown date.

Legacy and influence

While George Van Raemdonck was a notable artist in the Dutch press, he was far less famous in Belgium. Besides the 'Bulletje en Boonestaak' reprints in De Volksgazet, most of his drawings, comics and cartoons for the Dutch press were never released in his home country. In Belgium, Van Raemdonck was far more notable as a portrait painter. His portraits were praised for their honest depictions, and always reflected some of the inner nature of his models. A painting depicting his daughter is in the collection of the Antwerp Museum of Fine Arts. Nevertheless, he is widely considered the godfather of Dutch-language comics, both in Flanders and The Netherlands. While there had been notable Flemish and Dutch cartoonists before him, he was the first to create a successful, homegrown and long-running newspaper comic in the Dutch-speaking regions. In his wake came many other pioneers. In Belgium, Eugeen Hermans (Pink) became known as one of the first Flemish comic artists, working for newspapers like De Standaard and Ons Volk during the 1930s. In the Netherlands, the success of 'Bulletje en Boonestaak' resonated in other early newspaper comics, including 'Tripje en Liezebertha' by Henk Backer (1923), 'Krelissie en Dirrekie' by Albert Funke Küpper (1923) and 'Snuffelgraag en Knagelijntje' by Gerrit Rotman (1924). In addition, George Van Raemdonck was also an influence on Flemish artists, for instance Jan Waterschoot and Buth.

'Bulletje en Boonestaak' is still considered a classic of Dutch comics. Dutch poet Gerrit Kouwenaar was a celebrity fan of the series. Singer Nico Haak recorded a musical single, 'Bulletje en Boonestaak' (1981). Another fan of the series was the journalist and essayist Henk Hofland, who called the series "nicely unpedagogical and mischievous". A Flemish celebrity fan of 'Bulletje en Boonestaak' was Belgian blues musician Roland Van Campenhout, AKA Roland. In 1986, the Belgian cartooning contest George van Raemdonck Kartoenale was established, organized regularly by I.H.A. In 2022, Pascal Lefèvre scripted 'Gepeld Eike en Rode Tomat' (2022), an educational comic about Van Raemdonck, drawn by Greg Shaw and printed in Zandstraal/Le Dessableur, the magazine of the Belgian Comic Strip Center in Brussels.

Since 2003, two streets have been named after Bulletje en Boonestaak in the Dutch city Almere as part of its "Comic Heroes" district: the Bulletjestraat and the Boonestaakstraat. Another street is named after the cartoonist - the Van Raemdonckstraat. Van Raemdonck's legacy also lives on in the annual Dutch comic prize Bulletje & Boonestaakschaal, awarded since 2003 by the Dutch comic appreciation society Het Stripschap. On 19 April 2009, a memorial plaque designed by Eric Verlinden was attached to Van Raemdonck's former house in Boechout. At the same occasion, a local park and a street were renamed after Van Raemdonck, while a sculpture of both him and his characters was revealed in the park. The sculpture was designed by François Blommaerts. Unfortunately, the statue was vandalized on 10 November 2012 and even stolen on 28 August 2018. On 27 June 2021, a bench with a mosaic drawing depicting Bulletje and Boonestaak was revealed to the public in Nieuw-Vossemeer, in the presence of Van Raemdonck's granddaughter Cathy Collet. The bench was an initiative of the A.M. de Jong Museum and designed by Simon and Sandra Van Merriënboer. On 14 April 2022, it was announced that a path between the Populierenhof and the Van Raemdonck Park in Boechout was to be renamed "Bulletje en Boonestaakpad".

A.M. De Jong, George van Raemdonck and Bulletje & Boonestaak.

Expositions and studies

While his paintings have been on exhibit throughout his career - for instance during a 1931 exposition in Antwerp - Van Raemdonck's cartooning work became the subject of several overview exhibitions later in his life and after his death. One of the earliest was a 1965 show in Galerie Etcetera in Bergen op Zoom. Since 1974, the life and work of A.M. de Jong and his contemporaries has been the subject of many expositions in the A.M. de Jong Museum in Nieuw-Vosmeer. On the occasion of the 100th anniversary of 'Bulletje en Boonestaak' in May 2022, new expositions were opened in both the Dutch A.M. de Jong Museum and the Belgian Comic Strip Center in Brussels, Belgium.

In the Netherlands, Hans Stoovelaar and Jan Kooijman have dedicated several studies to the 'Bulletje & Boonestaak' comic, starting with the 1977 book 'In de Ban van Bulletje & Boonestaak', published by Nico Noordermeer. They also compiled the catalog that accompanied the 1979 Bulletje & Boonestaak exposition in the A.M. De Jong Museum, published under the D'Roodkoopren Knoop imprint. An updated edition was released in 2001. Between 2001 and 2012, Stoovelaar additionally released editions of the newsletter Bulletje en Boonestaak Bulletin. Also in 2001, the publisher Querido released a biography about A.M. de Jong by Mels de Jong and Johan van der Bol, 'A. M. De Jong, Schrijver'.