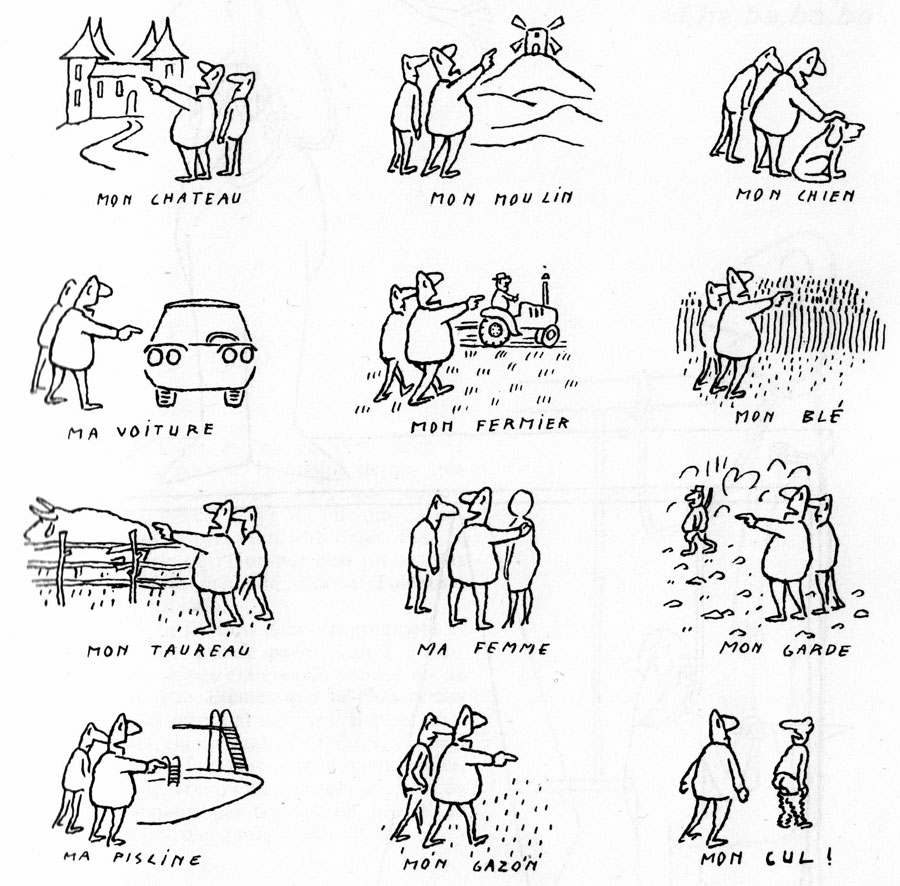

Cartoon by Bosc. Translation: "My castle. My mill. My dog. My car. My farmer. My wheat. My bull. My wife. My guard. My swimming pool. My grass." - "My ass!".

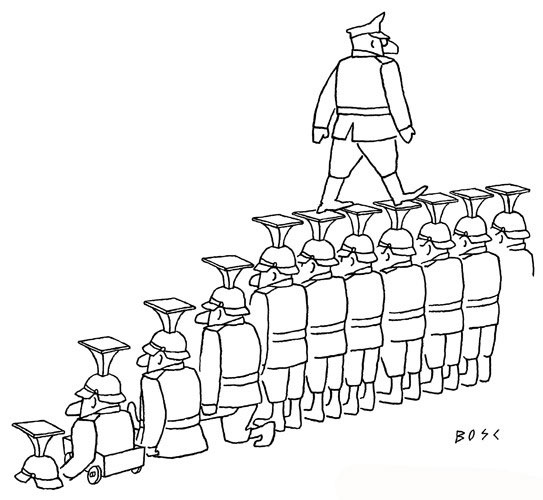

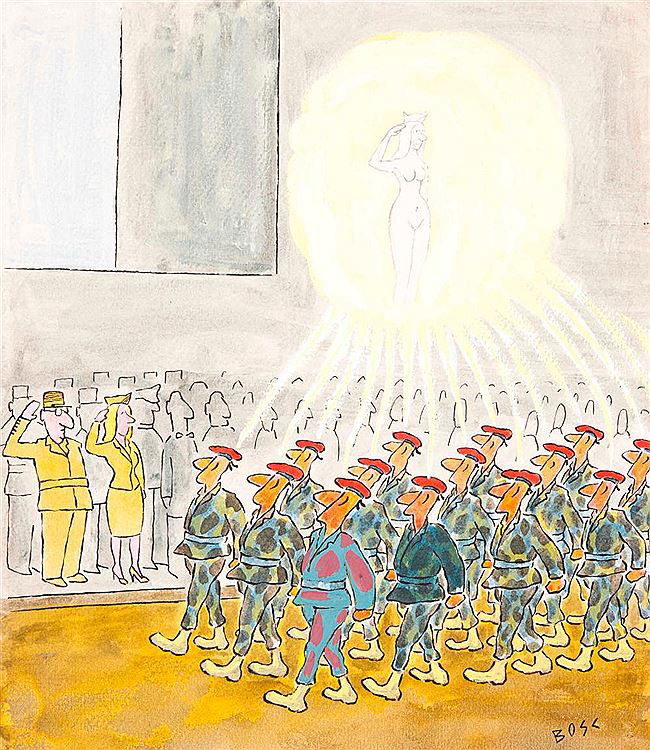

Jean Bosc was an influential French editorial cartoonist. His cartoons, making use of pantomime comedy, occasional speech balloons and comic strip sequences, have been translated in many languages. He was most notable as one of the regular cartoonists in the weekly magazine Paris Match (1952-1970). Bosc combined a minimalist graphic style with pitch black comedy, often directed at the military. His work won several awards. Bosc was also active as an animator, though his award-winning short, 'Voyage en Boscavie' (1958) is nowadays lost. Despite a successful career, Bosc took his own life at a young age, giving his black humor a disturbing undertone.

Early life and career

Jean-Maurice Bosc was born in 1924 in Nîmes as the son of a wine cultivator from nearby Aigues-Vives au Gard. Bosc studied at a technical college in Nîmes, where he always received the best grades in drawing, although he personally put his achievements in perspective: "I was the only person in my classroom who actually drew." Originally, Bosc was expected to follow in his father's footsteps and inherit the winery. But in 1945, the 20-year old enlisted as a volunteer for the army, inspired by his father, who had served in the Navy. It turned out to be the worst mistake of his life, as Bosc was sent to the French colony of Indo-China (nowadays roughly Vietnam) to combat Ho Chi Minh's independence-motivated troops, the Vietcong. He was taken prisoner-of-war and spent 120 days in a Vietcong prison, before being liberated. In 1948, he returned to France and was given a Croix de Guerre medal.

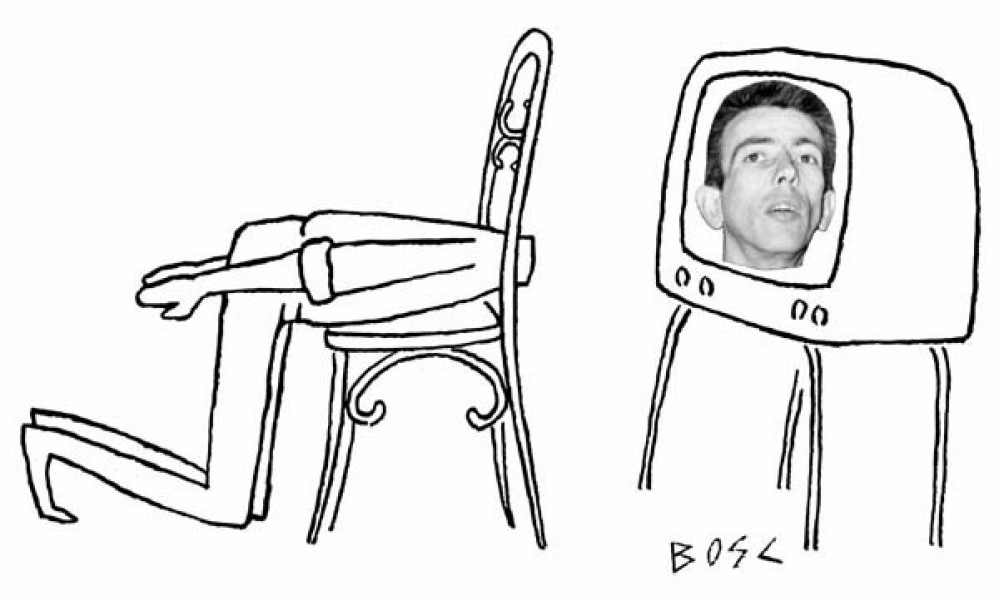

Cartoon by Bosc.

After spending three years mindlessly obeying orders, two of which in the Vietnamese jungle, Bosc was severely traumatized. "After what I've witnessed in Indo-China", he wrote, "I could no longer eat or sleep, ever." He later told his sister that he had shot dozens of fellow soldiers, saw gruesome fights and, while imprisoned, heard prisoners being tortured. She recalled that he could no longer stand loud noises and got furious whenever she wanted to kill a mere spider. Bosc became a lifelong opponent of war and militarism. As he tried to pick up work again in the family winery, the war veteran felt too weak physically. He could no longer operate a plow or work with other equipment. It has been speculated that Bosc may have had shell shock or, from a modern-day diagnosis, PTSD. At the time, however, there was no medical explanation for his condition. He would battle depression and physical stress for the rest of his life.

At his sister's advice, Bosc looked for a profession and a hobby that could give him a new, brighter goal in life. He studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Montpellier, tried painting and playing the piano and the violin. Later he moved to the town of Gournay-sur-Marne and from 1965 on, settled in Antibes, a seaside city in the Alpes-Maritimes department, where he became a member of the local Nautical Club.

Cartooning career

Under pen names like "Jm-Bosc" and "Scob", Bosc's earliest drawings appeared in magazines like Combat (1944) and L'Observateur (1950). It wasn't until June 1952, when he saw a cartoon book by Mose, that he decided to make cartooning a full-time career. He got in contact with Mose, who became both a mentor and personal friend. Other main graphic influences were Chaval, André François and Ronald Searle, while Bosc was also pals with Sempé. As luck would have it, Bosc enjoyed a veritable blitz cartooning career, despite having little graphic training. A mere five months after deciding upon his new life's path, his cartoons ran in the popular and nationally distributed weekly Paris Match. Debuting in its pages on 22 November 1952, chief editor Paul Chaland felt obliged to explain and defend Bosc's minimalist graphic style to his readers by describing it as "unskilled freshness". However, Paris Match readers accepted Bosc immediately, and for the next 12 years, he remained a staple in their magazine.

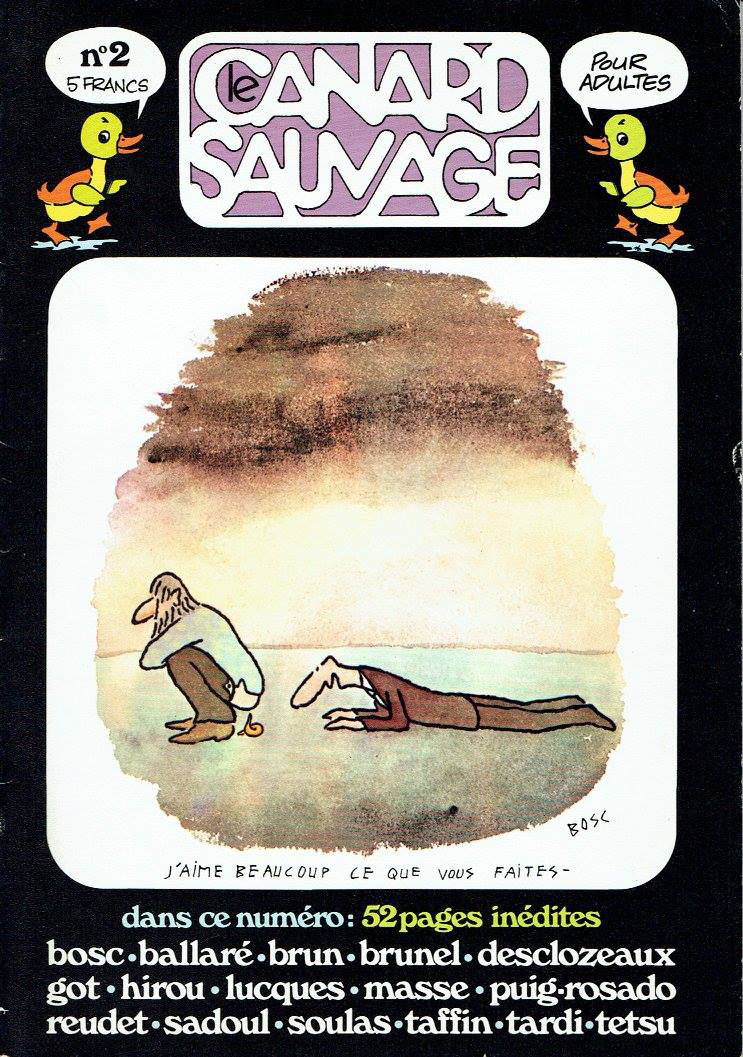

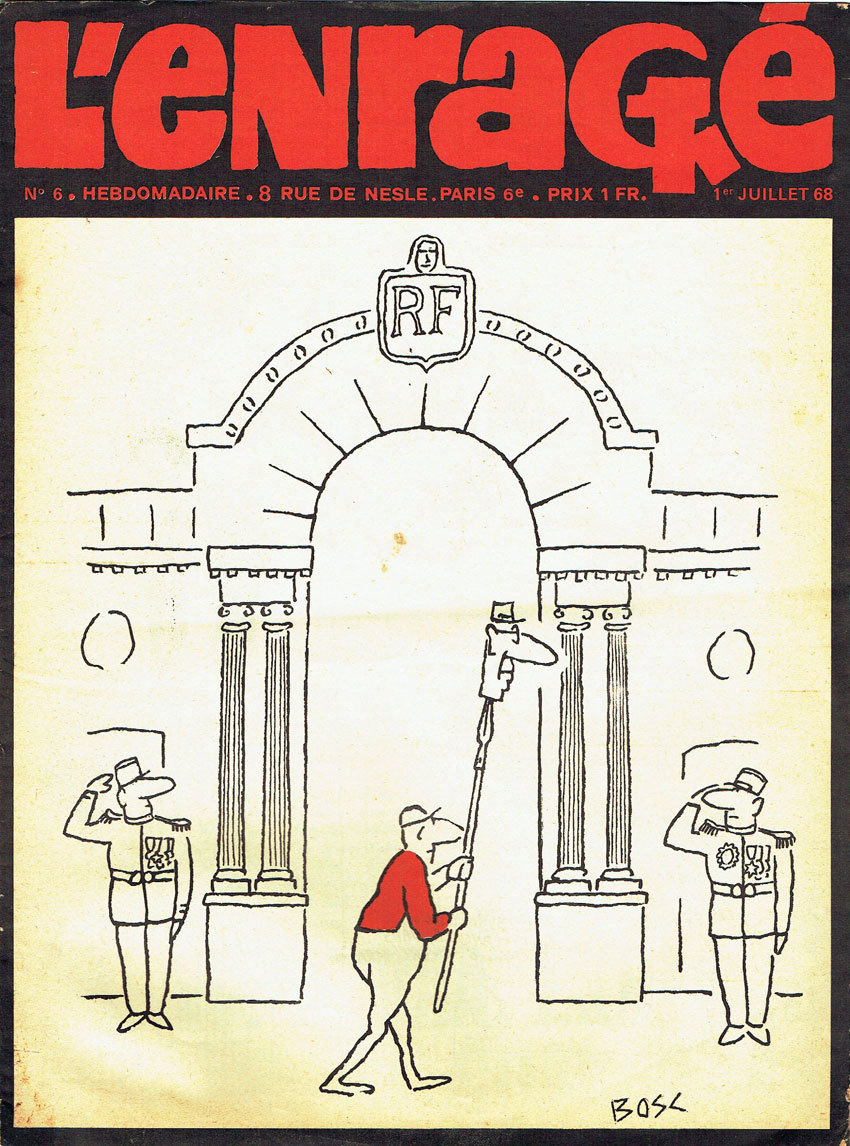

Cover illustration for Le Canard Sauvage issue #2 (Translation of the cartoon: "I love what you are doing.") and L'Enragé issue #6 (1 July 1968).

By 1953, his work was picked up by the American publisher Simon & Schuster, who printed some of his cartoons in the general compilation book 'The Best Cartoons from France' (1953). A year later, the Swiss-German publishing company Diogenes Verlag featured Bosc in another compilation book, 'Cherchez La Femme'. The first title completely devoted to Bosc alone was 'Gloria Viktoria' (Buchheim Verlag, 1955), followed by his first French-language book 'Petits Riens' (Hazan). Other cartoon book collections published during his lifetime were 'Mort Au Tyran' (Pauvert, 1959), 'Les Boscaves au Feu' (1959), 'Les Boscaves' (1965), 'Si De Gaulle Était Petit' (1968), 'La Fleur Dans Tous Ses États' (Claude Tchou, 1968), 'Je t'Aime' (Albin Michel, 1969) and 'Le Couple' (Gerfau, 1970).

His cartoons also ran in Action, Le Canard Sauvage, Caravelle, Constellation, Détective, Éclats de Rire, Écho de la Mode, Elle, L' Enragé, L'Expréss, Franche Dimanche, France Nouvelle, France Observateur, Hara-Kiri, Jours de France, Lectures Pour Tous, Minute, Le Monde, Notre Époque, Le Nouveau Candide, Le Nouvel Adam, Lui, Optimiste, L'Os à Moelle, Les Parisiens, Pariscope, Populaire Dimanche, Radar, Ridendo, Le Rire, Semaine du Monde, Samedi-Soir, Télé Gadget, La Vie Catholique Illustrée and La Vie Électrique. In the English language, Bosc appeared in the U.S. magazines Esquire, Harvey Kurtzman's Help! and the British satirical magazine Punch. Canadian readers knew him from Oui, while in West-Germany he appeared in the newspaper Die Zeit. Bosc's cartoons have additionally been translated in Bulgarian, Dutch, German, Italian, Iranian, Polish, Serbian, Spanish, Swedish, Turkish, Taiwanese and Japanese.

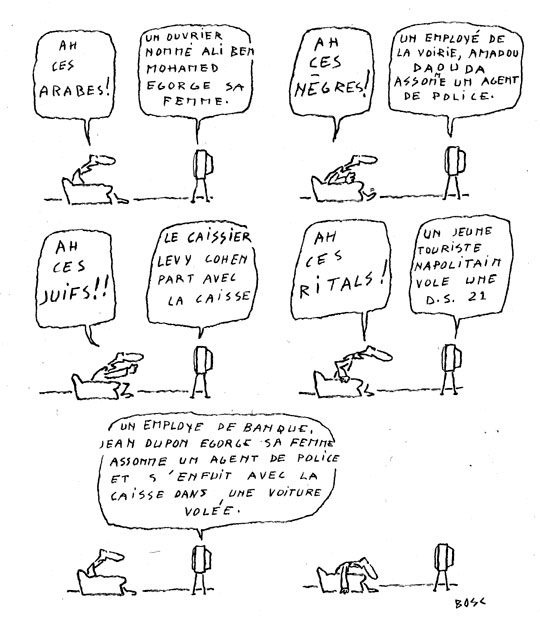

From: 'Je t'aime' (1969). The man watches a TV report about four foreigners who each committed four specific crimes, which he is quick to blame on "Arabs, Negroes, Jews and Italians". The journalist then mentions a man with a French-sounding name who committed all previously mentioned crimes on his own.

Style

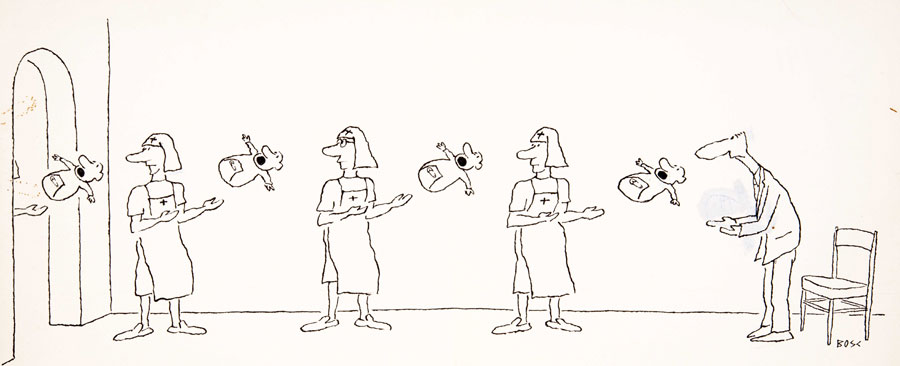

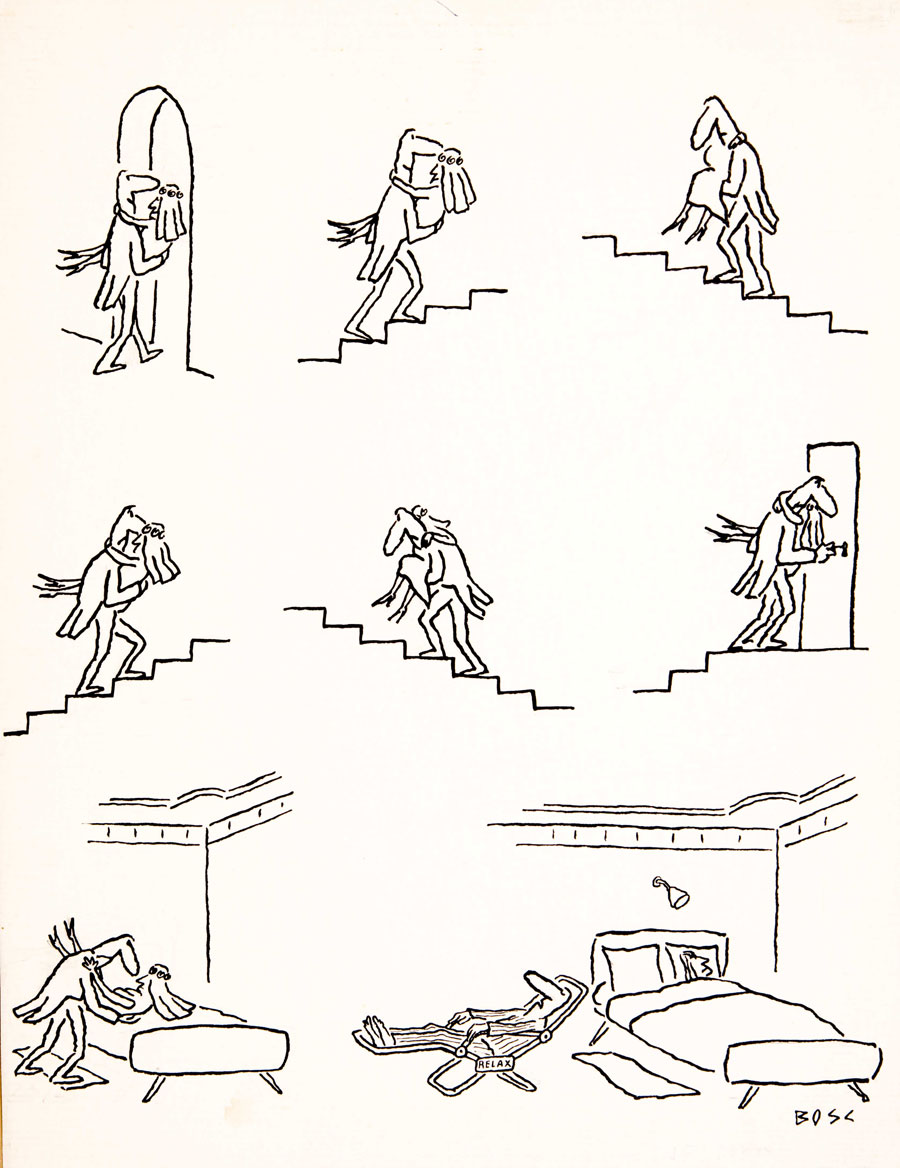

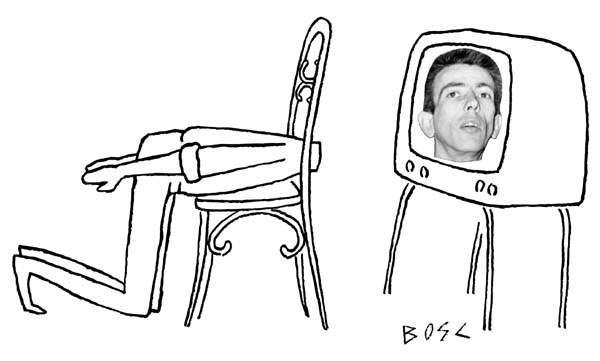

Being almost completely self-taught, Bosc used simple linework, without much detail. The backgrounds were often white voids, reduced to the bare minimum of what he needed to communicate his gags. His characters have a naïve look, giving his drawings a seemingly innocent aura. Many have large, bulbous noses. Interviewed by Bernard Vadon for Nice-Matin (31 October 1970), he reflected that he had no idea himself why he drew his characters with such huge nasal organs. In another article, from Midi Libre (18 March 1959), he reflected on his trademark style: "My style looks the way it does, because I don't know how to draw." Some of his cartoons make use of photo collage. Under the apprenticeship of Alain Pouliquen and Renato, he also made ceramist sculptures from 1965 on.

However, the seemingly innocent, child-like atmosphere of his cartoons, contrasted sharply with the content. Many of Bosc's cartoons were characterized by black comedy. He poked fun at child abuse, marital troubles, divorce, warfare, murder, suicide and funerals, and also mocked conventionality, patriotism, authority and militarism. Just like his contemporaries Chaval, Copi, André François, Mose, Sempé, Siné and most of the renegade cartoonists of Hara-Kiri magazine, Bosc had lived through the Nazi occupation in World War II. After the Liberation, he felt disgusted by his country's attempts to keep subjugating their overseas colonies to similar oppression and exploitation. President Charles de Gaulle was the sum of everything they hated: a conservative politician who didn't agree with the growing sentiment of anti-colonialism, the sexual revolution and disregard for Church, army and family values. Bosc often ridiculed De Gaulle in his work. Once, the cartoonist was fined 3,000 francs, with a month's probation, for daring to mock the army in a magazine. Bosc's work revealed he had no respect for politicians. Interviewed by Paris Match in 1965, Bosc claimed that Alexander the Great was his "favorite great statesman, since he died at age 33."

Jean Bosc.

Animation career

In 1958, Bosc collaborated with Claude Choubli and Jean Vautrin on the animated short 'Le Voyage en Boscavie'. Set in a fictional country of Boscavia, named after himself, the film is a satirical look at human stupidity, found in the army, traffic and at home. In some theaters, the cartoon played before showings of Jacques Tati's classic 1958 comedy film 'Mon Oncle' (and not 'Les Vacances de Mr. Hulot' as many sources incorrectly claim). Almost a decade later, Bosc also made another cartoon, 'Poor President' (1967), broadcast on a TV network in Stuttgart, and another short titled 'Le Chapeau'. All his films are nowadays presumed lost.

Recognition

In January 1958, Bosc's animated short 'Le Voyage en Boscavie' received the Prix Émile Cohl, followed by the 1959 Grand Jury Prize at the Biënnale of Venice. On 1 April 1965, he was honored with the Humor Award, on the behalf of the magazine Lui. On 27 October 1970, his book 'Je T'Aime' (1970) received the Grandville Grand Prix for Black Comedy, while on 15 July 1972, the city of Avignon bestowed him the Grand Prix for Humor. Posthumously, Bosc received the Monnaie de Paris twice, in 1971 and 1981. In 1996, a street in Aigues Vives was named after him. On 5 September 1997, a hall was named after him in the same town. In 2000, a residence in Codognan was named after him. Another street was named after Bosc in St. Just le Martel, inaugurated on 2 October 2005.

Between 25 November and 24 December 1970, Bosc's work was on display at the Galerie Christiane Colin in Paris. In February 1982, Bosc's cartoons were posthumously exhibited in the Wilhelm Busch Museum. and in April 1986 under the title 'Vive Bosc!' at Ichtus and in Sommières. In June 2007, his work was part of a city exhibition in Cluny. Under the title 'Bosc's Balkantour', his drawings were also on display in the Branko Najhold in Serbia. Between 17 October 2014 and 1 March 2015, Bosc's cartoons were exhibited in the Tomi Ungerer Museum in Strasbourg, under the title 'Bosc, Humor in Black Ink'. Between 6 May and 10 September, his work was on display in the Musée Peynet in Antibes, while between 17 and 18 September 2018, Bosc's work appeared in the Drouot Maison Leclere in Paris.

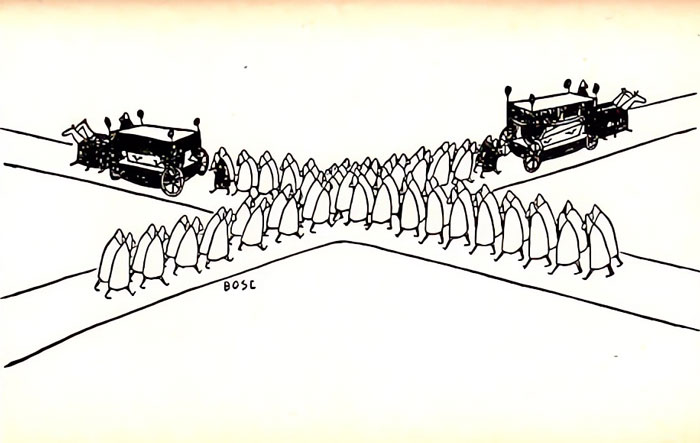

Cartoon by Bosc, used on his gravestone.

Death

In his final years, Bosc shared a house with his wife and his aging mother. Tragedy struck in 1968, when his good friend and colleague Chaval committed suicide. In June 1969, Bosc had a mental breakdown and was hospitalized. Suffering from an illness depigmenting his skin, he weakened more and more, often to the point of no longer being able to stand on his own two feet. He went in and out of clinics, even tried electroshock therapy, but nothing helped. As his health deteriorated, so did his mood. From 1970 on, he basically quit drawing cartoons.

In 1973, the depressed cartoonist went to his garage and shot himself. He was 48 years old. In his suicide letter, he asked his sister to put a reproduction of one of his cartoons on his grave, namely the one where a funeral procession passes by a billboard, advertising the highly inappropriate laughing cow mascot from the cheese brand La Vache Qui Rit. She didn't fulfill his final wish entirely. Instead, she picked out a different funeral-themed cartoon, in which two funeral processions cross each other from two different directions.

In the next issue of Charlie Hebdo, Wolinski wrote a personal "in memoriam" to Bosc. In 1991, a collection of unpublished and uncensored drawings by Bosc was published by Cherche Midi, with a foreword by Wolinski.

Legacy and influence

In France, Jean Bosc's cartoons have been a strong influence on Jean-François Batellier, Catherine Beaunez, Roger Blachon, Claire Bretécher, Michek Bridenne, Cabu, Copi, Christophe Delvallée, Serge Dutfoy, Georges Million, Jean-Marc Reiser, Rolandaël, Sempé, Tassuad and Wolinski. In Belgium, he was an inspiration to Benoît, Gal, Philippe Geluck and Jean-Louis Lejeune. Canadian admirers have been Guy Badeaux (Bado) and Jacques Goldstyn, while his work also found fans in Argentina (Quino), Bulgaria (Georgi Dumanov), Equador (Bonil), Israel (Gil Gibli and Belgian-born Michel Kichka), Italy (Ugo Sajini), Portugal (Carlos Brito), Spain (Kap-Gargots, Fernando Puig Rosado), Turkey (Izel Rosental, Sema) and the United Kingdom (Terence Parkes). Veteran cartoonist Ronald Searle also admired Bosc's work, and vice versa. They kept a written correspondence for decades.

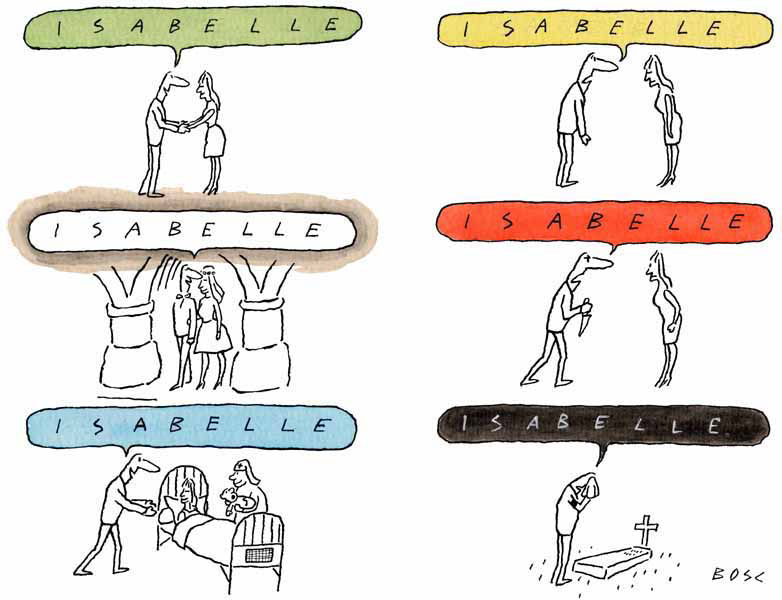

A comic strip by Bosc about a man meeting a woman, marrying her, having a child and then murdering her and weeping by her grave, inspired film maker Moïse Maatouk to create a 1972 short film based on this plot, titled 'Isabelle'. According to Maatouk's correspondence with the official Bosc website, maintained by the cartoonist's nephew Alain Damman, this particular film is nowadays lost.

When Paris Match asked Bosc in 1965 what he liked best about life, he answered: "Love with a large 'L'." When asked: "What else?", he replied: "Love with a little "l"." The most complete overview of Bosc's work can be read in 'Bosc, ou l'Éclat de Vivre' (Drouot- Leclerc, 2016) and 'Mon Oeuvre' (Cherche Midi, 2016).

Self-portrait (1955).