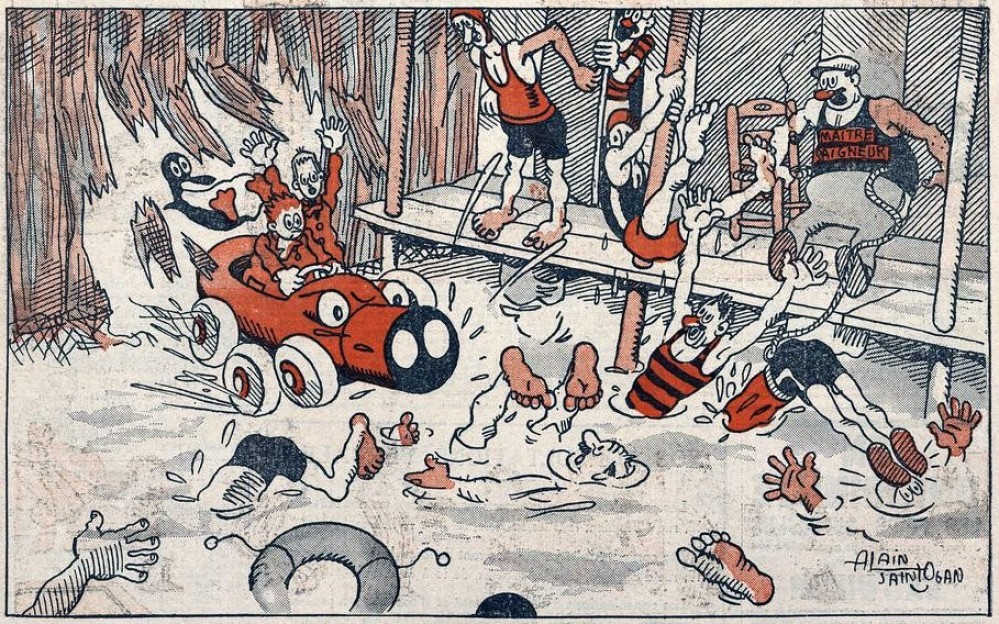

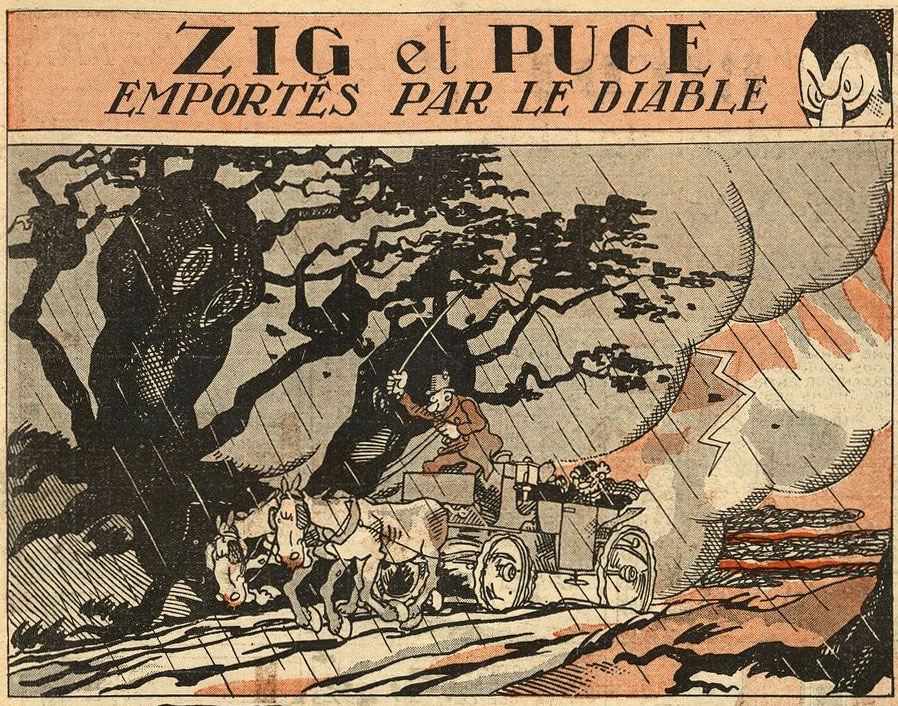

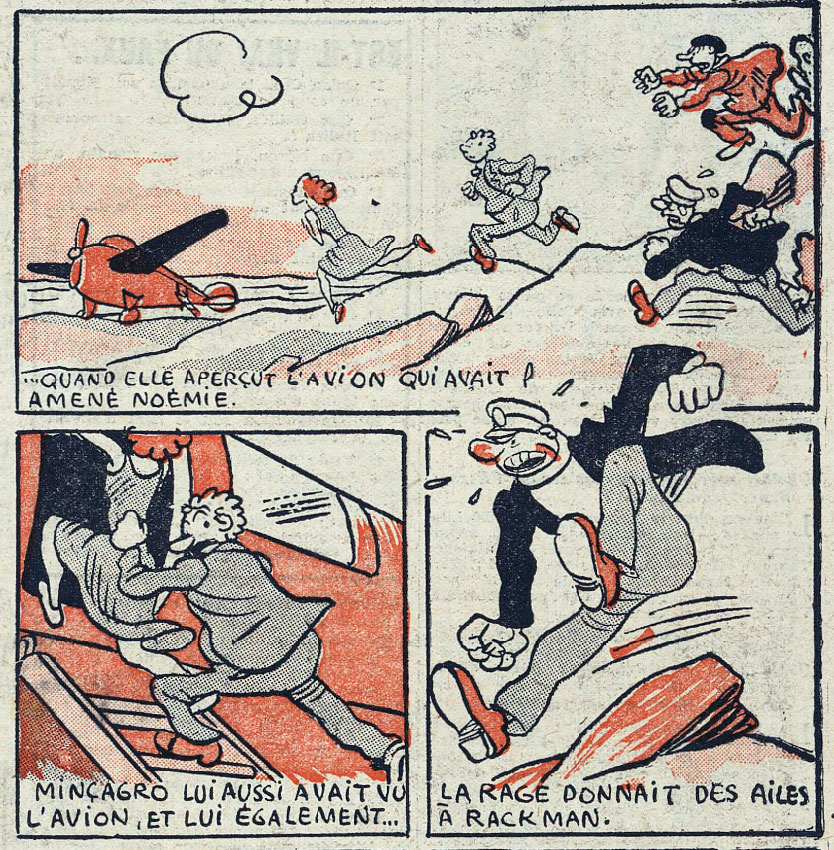

Zig et Puce - 'Mauvais Débuts' (Dimanche-Illustré, 10 April 1932).

Alain Saint-Ogan was a French comic artist, most famous for his children's adventure series 'Zig et Puce' (1925-1956), starring two boys and their penguin Alfred, who became the breakout character. Saint-Ogan is commonly regarded as the true father of the modern French comic strip, popularizing both speech balloons and the newspaper comic genre. Above all, he turned French comics into the industry that it remains today. Saint-Ogan merchandised his characters through books, toys, media adaptations (radio, stage plays, songs) and public events. He proved the commercial viability of comics in French media and was an influence on many pre- and post-war Franco-Belgian adventure, funny animal and gag comics. Among his other, lesser-known works were 'Prosper L'Ours' (1933-1939) and 'Monsieur Poche' (1934-1937).

Early life and career

Alain Marie Joseph Paul Louis Fernand Lefebvre Saint-Ogan was born in 1895 in Colombes, a commune in the northwestern suburbs of Paris. He was the only child of the journalist Joseph Lefebvre Saint-Ogan and his second wife, Louise Claudine Venaty. From a previous marriage, his father already had four children, of which Bertrand (1891-1977) later also became an illustrator/cartoonist, using the pen name Bert-Malet. Later living in the Parisian neighborhood Passy, Saint-Ogan's father moved to Caïro, Egypt, where in 1906 he became chief editor of the newspaper L'Etendard Égyptien. Alain later joined him for three months, developing a passion for the press himself. At age 12, Alain Saint-Ogan founded a bi-monthly (appearing twice a month) magazine, Le Journal des Deux Mondes, making him the youngest known chief editor in the world. According to reports at the time, Le Journal des Deux Mondes managed to have around 2,000 subscribers, among them French president Armand Fallières and stage actress Sarah Bernhardt. Saint-Ogan received a letter from Bernhardt, in which she said that she didn't pay for subscriptions, but promised to send him postcards with her signature as a compensation. Interviewed by Jean-Louis Durher (Phénix #40, 1974), Saint-Ogan said that he unfortunately lost her correspondence due to World War II. Some of Saint-Ogan's articles also ran in Le Matin (July 1913) and the London newspaper The Daily Chronicle.

Saint-Ogan enjoyed science fiction novels, singling out Jules Verne, H.G. Wells and illustrator G.Ri as his personal favorites. In his later comics, he sometimes used scenes inspired by their books, like in 'Zig et Puce et L'Homme Invisible' (1949), in which the duo meets The Invisible Man.

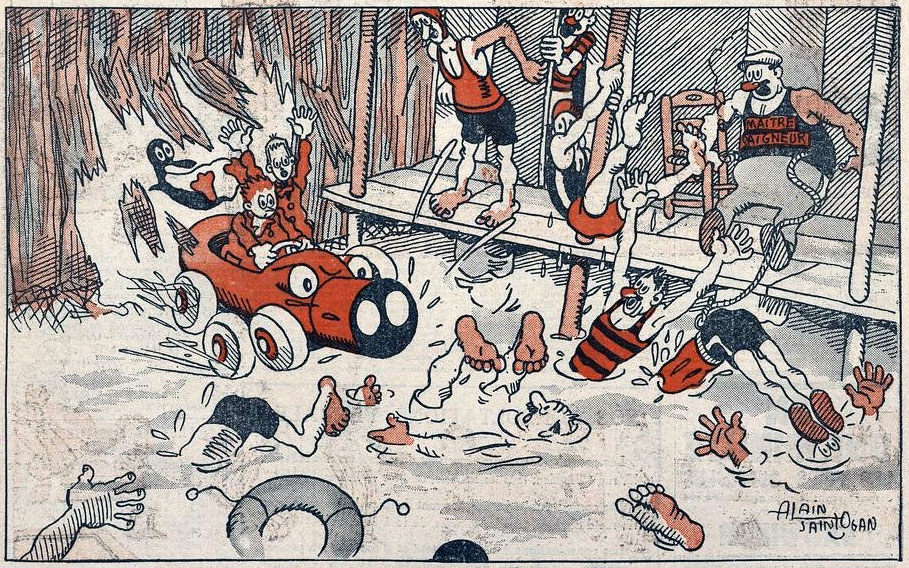

Promo for the Salon des Humoristes (1927).

Early graphic career, influences and development of style

In the pages of his self-published Le Journal des Deux Mondes, Saint-Ogan printed his earliest illustrations and humorous cartoons. His cartoons also ran in the newspaper Le Matin (1910). To hone his graphic skills, Saint-Ogan studied at the École Nationale des Arts Decoratifs in Paris from 1914 on. The same year, he also showed his drawings to the cartoonist Benjamin Rabier, who encouraged him to keep on drawing. However, the First World War interrupted his studies. In 1916, Saint-Ogan was drafted and sent to the Balkans. He didn't see much combat, as the military authorities found his graphic talent very useful for propaganda magazines, like the anti-German weekly L'Anti-Boche. Although Saint-Ogan never returned to the Academy, he had acquired enough graphic skills and press connections to work as a full-time cartoonist after the war. He moved to Paris, becoming a member of the Société des Dessinateurs Humoristiques ("Society of Humorous Cartoonists") who held the annual Salon des Humoristes exhibitions.

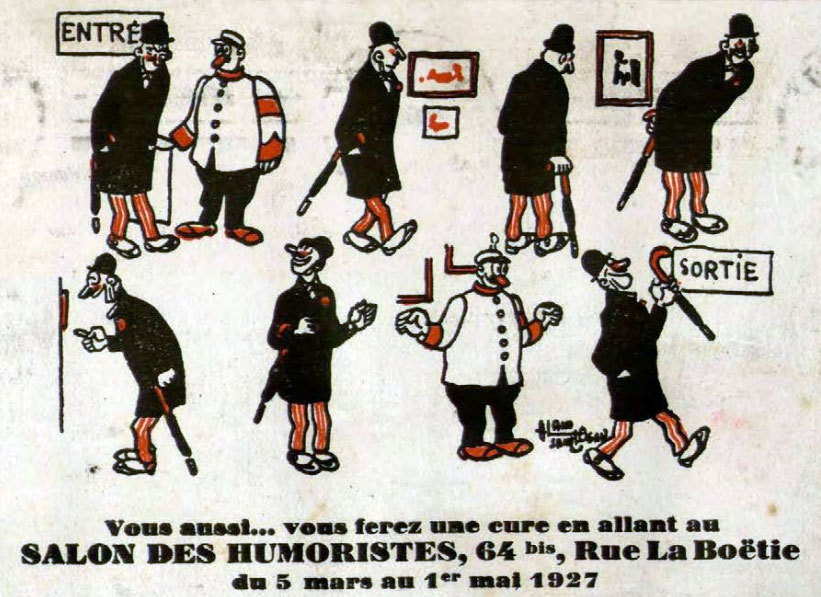

'Le Voyage de Bob et Bobette avec Leur Chien Gaëtan' (1929).

Saint-Ogan was house cartoonist for the Parisian dailies L'Écho de Paris (1918-1922), Le Petit Journal (1918), L'Intransigeant (1918-1929) and Le Dimanche Illustré (1925-1936). He also made gag comics in the children's magazine La Semaine de Suzette, including 'Les Aventures de Mique et Trac' (February 1925-January 1926), starring gags with a cat and a dog, and 'Tiennette Fait du Cinéma' (January-December 1926), about a little rich girl setting out to make a film with her friends. Saint-Ogan's art also appeared in La Dépeche du Midi and Le Parisien Libéré. In the late 1920s, his political drawings appeared in the satirical magazine Le Charivari. In 1929, he also drew an advertising picture story for the shoe brand Cecil, titled 'Le Voyage de Bob et Bobette avec Leur Chien Gaëtan' (not to be confused with the French-language name of Willy Vandersteen's 'Suske en Wiske').

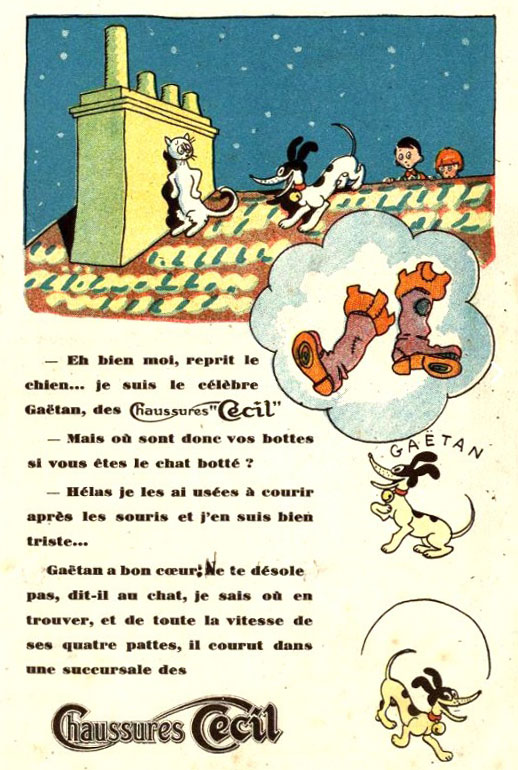

Elaborate artwork in the 16 April 1933 episode of 'Zig et Puce'.

Through his father's travels and professional connections in the press industry, Saint-Ogan had access to American newspapers too. He observed that their daily and Sunday comics were very popular among readers. He also discovered that U.S. comic artists predominantly used the speech balloon format, while in Europe most picture stories were printed in the text comic format, with narration and dialogue underneath the images. As a result, many European editors often reformatted these foreign balloon comics into text comics. In France, Émile Tap's 'Sam et Sap' (1908) was an early example of a home-made balloon comic, but it had not made much of an impact. Saint-Ogan felt that speech balloons were more direct in communicating characters' motivations to the reader. In Le Dimanche Illustré, one of the papers he contributed to, Martin Branner's 'Winnie Winkle' (which ran under the translated title 'Bicot') was a strong influence in this regard. Saint-Ogan started adapting speech balloons more regularly, becoming the trendsetter in French comics.

Saint-Ogan was also one of the first French comic artists to publish his series in newspapers. Since most other European comic creators of the 1920s were working predominantly in weekly or monthly humor magazines, they had the time to make very elaborate, precise illustrations. Since Saint-Ogan had to make far tighter deadlines in newspapers, he settled on a less detailed, more simplified linear style. He was inspired by the elegance and simplicity of the then-popular Art Deco movement. Saint-Ogan's time-saving graphic style also had a strong impact on other European comic artists, being a direct link to Hergé's "Clear Line" style.

In the previously mentioned Phénix interview, Saint-Ogan reflected that when he debuted, comics were regarded as charming, unpretentious children's entertainment. Artists used cheap material, often doing all the work (writing, inking, colorizing) on their own. Since everything was made for daily or weekly serialization, most plots were just improvised as they went along. Although Saint-Ogan appreciated the fact that he lived long enough to see comics be recognized as an art form, he also regretted this evolution: "The old comics were less advanced, but they had a quality drawings of today no longer have: homogeneity. Nowadays, it becomes too much. You have a separate scriptwriter, a main designer who only draws silhouettes, cars are drawn by a specialist, houses by an architect and it's so terrible that most of it doesn't always properly match." Saint-Ogan also felt that the realistic precision of these later-day comic artists eliminated the cartoony nature and fantasy of the comics of the early days: "When we drew a car, we took specific care to make it humorous and not imitate a real-life model, since we regarded this as advertising." Scientific progress also banalized people's imagination: "There was a time one could imagine the Moon being inhabited. Now that we're able to travel to the Moon, it's no longer possible." Though Saint-Ogan did acknowledge that many of the modern-day comic artists of his time were "very strong."

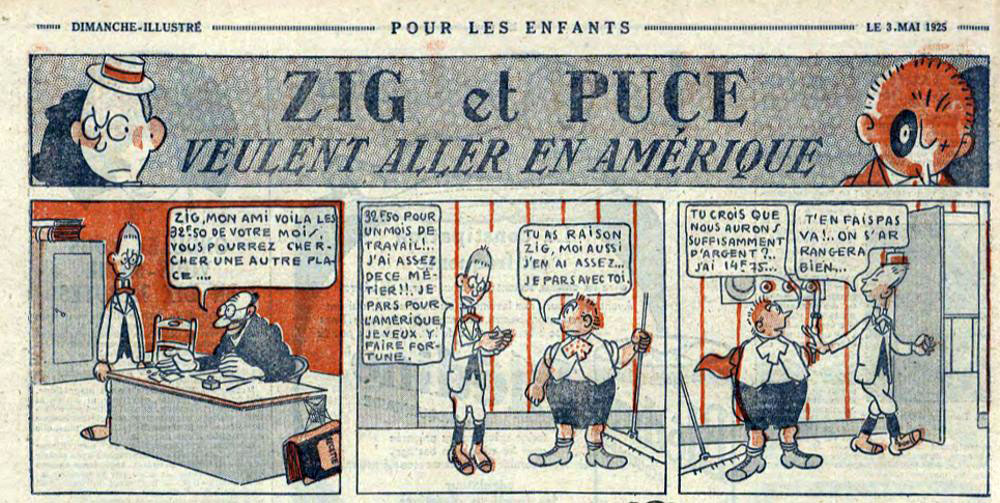

Debut strip of 'Zig et Puce' (3 May 1925).

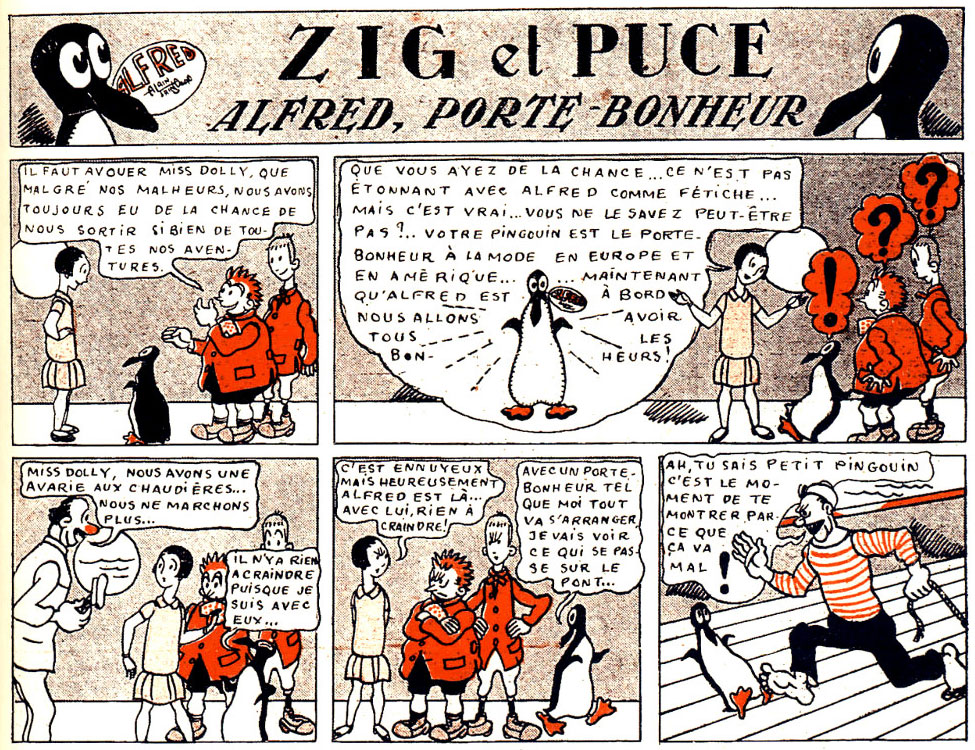

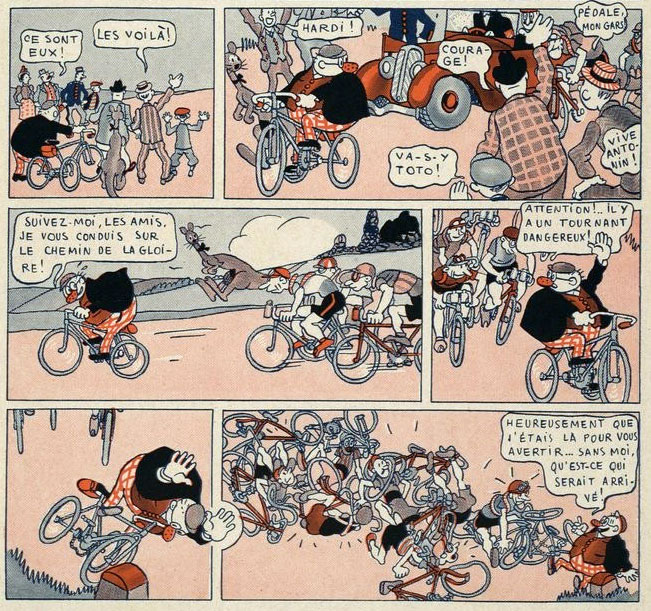

Zig et Puce in Dimanche-Illustré (1925-1934)

On 3 May 1925, the first episode of 'Zig et Puce' appeared in Le Dimanche Illustré, the Sunday children's supplement of the newspaper L'Excelsior. At the time, this magazine only ran two comic features, both foreign translations, namely Martin Branner's 'Bicot' ('Winnie Winkle') and Sidney Smith's 'La Famille Mirliton' ('The Gumps'). Much like Émile-Joseph Pinchon's 'Bécassine' 20 years earlier, 'Zig et Puce' also came about as last-minute filler. The editors were one advertising page short on the final page, so Saint-Ogan was asked to draw a replacement comic. The title duo consists of two young boys. Zig is tall, slender and clean-cut, while Puce is short, chubby, with spiky red hair. Originally, every episode was a one-page gag, built around their repeated attempts to travel to "America" and "get rich". This developed into a serialized narrative, which readers enjoyed so much that the editors of Le Dimanche Illustré moved 'Zig et Puce' to the center pages of each issue, eventually dropping 'The Gumps'. From that point on, Saint-Ogan made 'Zig et Puce' less punchline-driven and more focused on cliffhangers.

The 'Zig et Puce' stories are a mixture of exotic globe-trotting adventures and trips to fantasy worlds. The duo, for instance, meets the man-eating giant from the fairy tale 'Hop-O'-My Thumb'. In 1934, Saint-Ogan also drew a time travel narrative in which the gang ends up in the then-faraway year 2000. In a particularly eerie scene, Zig and Puce notice the gravestone of "their creator", with "1995" as his death year (in reality Saint-Ogan would pass away in 1974). The children regret his death, but also feel he was "a little intrusive", since "we couldn't lift a finger or he would tell the entire world about us."

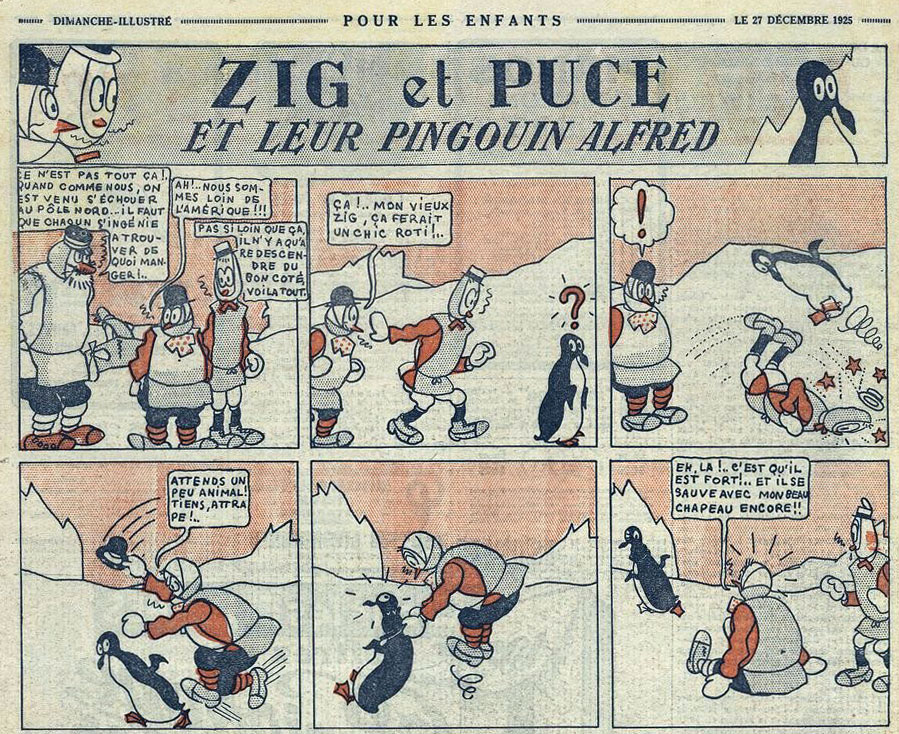

'Zig et Puc'. Debut of Alfred the penguin on 27 December 1925.

Zig et Puce: Alfred

In the debut year of 'Zig et Puce', the two boys ended up on the North Pole, where on 25 December 1925, they noticed a penguin who soon became the third main cast member. They named the bird Alfred and adopted him as their pet. Some readers have suggested that Alfred is actually a Great Auk, since his size is closer to this nowadays extinct bird and Great Auks actually lived in the Northern Hemisphere, whereas penguins are only found in the Southern Hemisphere, close to the Antarctic. However, in his 1974 Phénix interview, Saint-Ogan acknowledged that Alfred is just a penguin and his appearance on the North Pole was simply a common mistake. The artist originally just intended Alfred as a mere plot device to let the boys eat a penguin in order to survive in the harsh conditions on the North Pole. But he didn't have the heart to kill the bird, so he became Zig and Puce's pet companion. Alfred acts like a real animal most of the time, but whenever he wanders off on his own, Saint-Ogan lets him talk, so readers can follow his line of thought. Alfred often overestimates his own abilities, getting himself into trouble. Yet occasionally his ruthlessness also rescues Zig and Puce out of sticky situations.

Alfred quickly became the series' break-out character. In the story 'Zig, Puce et Alfred' (1929) the bird turns ill and is declared dead. Many readers felt saddened by the passing of the cute animal, but Saint-Ogan eventually brought him back. As it turns out, Alfred could be revived by just putting him in a refrigerator for a few hours.

Zig et Puce: other side characters

On 29 May 1927, a female cast member was introduced in the 'Zig et Puce' comic, Dolly. A girl around Zig and Puce's age, Dolly is the niece of a rich American businessman who produces rubber stamps. He made his debut on 14 August 1927, but never received a name in the original series. It wasn't until the 1960s reboot by Greg that he became Dolly's father instead of her uncle, and christened Poprocket. Zig and Puce met another animal friend on 4 March 1928: Marcel, a stubborn and easily agitated horse. Whenever he gets angry, only military music can calm him down. On 23 February 1930, the series also received a recurring antagonist, Charley Musgrave. Musgrave is Dolly's cousin and might inherit her uncle's fortune if she would "suddenly" pass away. As a result, he conjures up various schemes to get rid of her. Another thing the series needed was a wacky scientist, who made his appearance on 16 October 1932, but only received a name seven years later: Professeur Médor.

On 29 January 1933, the little princess Yette from the fictional Balkan country of Marcalance was introduced. The final recurring character in the series is private detective Hector Hameçon. Debuting on 19 September 1946, he would love to be the "hero" of the series, but constantly makes a fool out of himself. Arrogant and unpredictable, he is often a nuisance to Zig and Puce, sometimes even unwillingly getting them into more trouble. He is so dumb that villains can use him as a pawn.

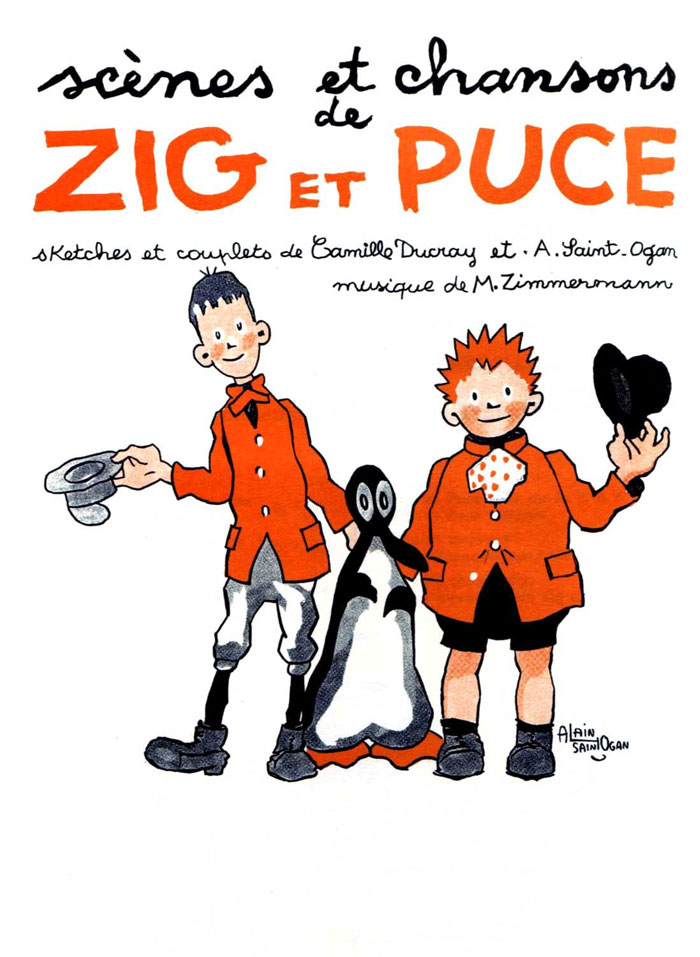

'Zig et Puce à New York' comic book and 'Zig et Puce' songbook.

Zig et Puce: success

In a time when novels, film and comics were children's only access to faraway countries, 'Zig et Puce' struck a chord with young readers. Their adventures instantly became very popular and the editors of Le Dimanche Illustré received several letters asking for more stories. The comics were also collected in book format by Hachette, and 'Zig et Puce' was translated into more than 11 languages. In the 1920s and 1930s, it ran in the Flemish children's magazine Zonneland under the title 'Loetje en Loutje', while in the Dutch version of Zonneland the duo was known as 'Van Ted en Minet'. In the 1940s, they ran in the Flemish magazine Bravo under the title 'Zig et Puk'. During their 1960s revival in Tintin, 'Zig et Puce' was translated into Dutch as 'Kees en Klaas'. 'Zig et Puce' was also translated into German, Portuguese, Italian ('Tip e Top') and Spanish ('Zig et Zag').

Thérèse Lenôtre adapted the series into five musical plays, namely 'Zig et Puce' (1927), 'Zig et Puce et le Serpent de Mer' (1929), 'Zig et Puce Policiers' (1934), 'Zig et Puce' (1936) and 'Zig et Puce en Angleterre' (1950). In April 1932, a series of six musical plays was released on LP, with actresses Madame Janyl and Suzanne Feyrou voicing Zig et Puce. In 1937, Lenôtre also adapted the series into a radio play. More than half a century later, Chantal Goya, known for her children's songs, also recorded a song about 'Zig et Puce' (2006).

Self-marketing for the Alfred dolls in 'Zig et Puce Millionnaires' (1928).

In 1928, Alfred the penguin was made into a stuffed toy. Various stars from the Parisian nightclub life, like Mistinguett, Yvonne Printemps and Josephine Baker, all bought one and carried it with them in public. Even French president Gaston Doumergue kept Alfred on his desk. And when U.S. aviator Charles Lindbergh made his famous 1927 solo flight across the Atlantic Ocean, he took a stuffed toy depicting Pat Sullivan and Otto Messmer's 'Felix the Cat' with him. Upon his arrival in Paris, he received an Alfred doll as a gift. Saint-Ogan didn't shy away from promoting his merchandise. In one storyline, 'Zig et Puce Millionnaires' (1928), Dolly shows Zig, Puce and Alfred the stuffed toy version of the penguin. On 28 April 1932, Saint-Ogan and Benjamin magazine also organized a children's gala in the Cirque d'Hiver, where he hired 12 penguins from a zoo to join him in a parade.

Zig et Puce in other magazines (1936-1943)

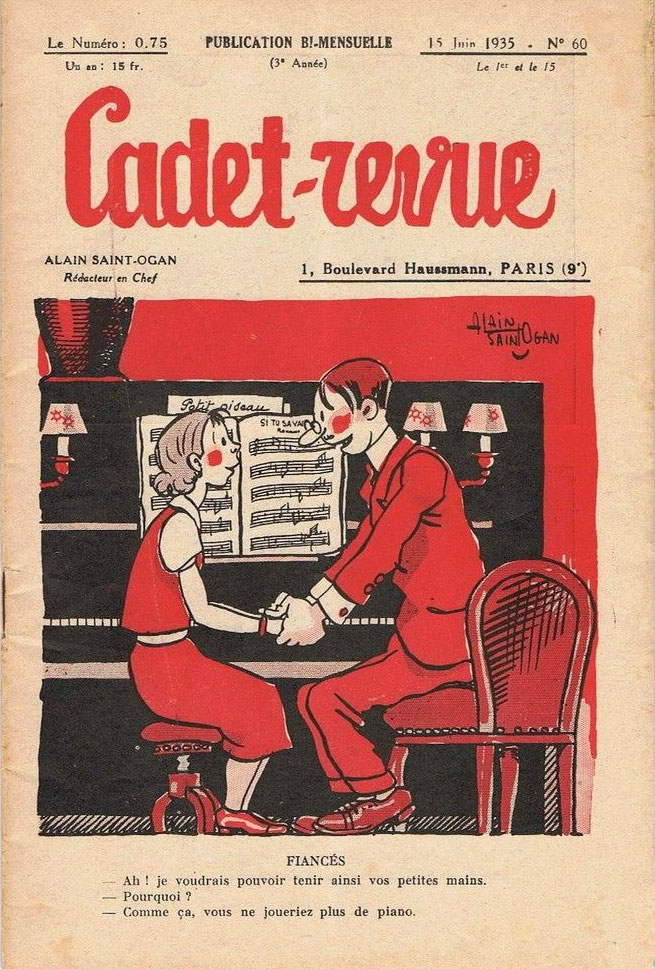

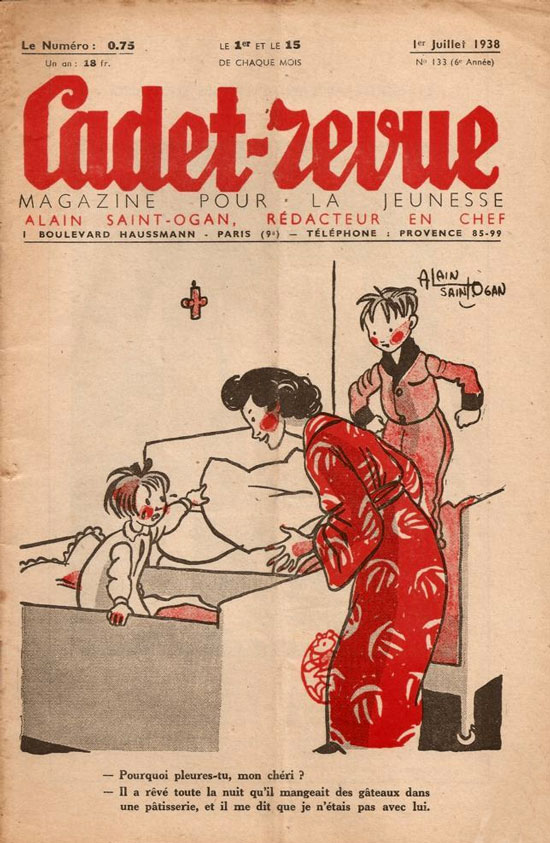

On 7 October 1934, the 'Zig et Puce' comic was discontinued in Dimanche-Illustré. After a hiatus, the characters found a new home in Le Petit Parisien, the children's supplement of Le Parisien, where they appeared from 23 January until 13 August 1936 under the title 'Les Nouvelles Aventures de Zig et Puce'. The adventures in this magazine are among the few that were never made available in book format at the time. Similarly, the 1938 book 'Zig et Puce Ministres' is their only adventure published directly in book format, without previous serialization. Reprints of older 'Zig et Puce' stories then appeared in the magazines that Saint-Ogan edited, Cadet-Revue (1939) and Benjamin (1941-1943). However, it would take until after World War II before 'Zig et Puce' experienced new adventures.

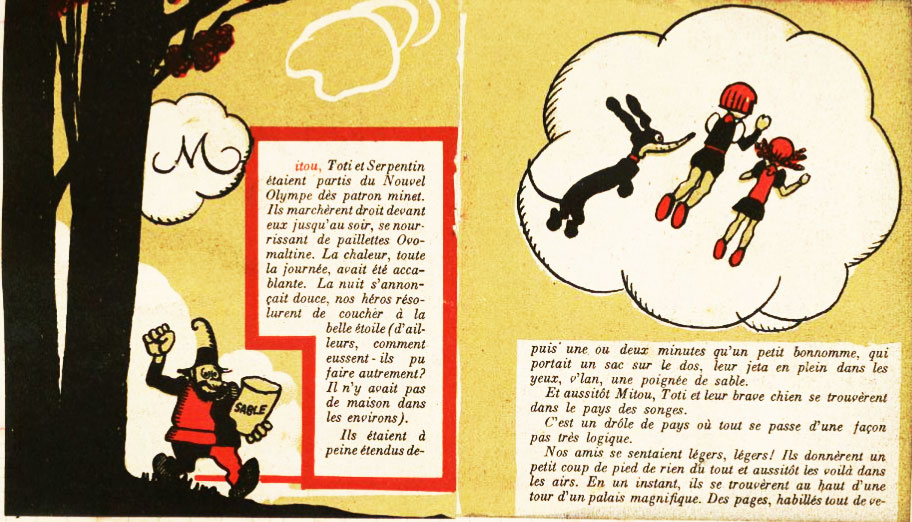

'Les Aventures de Mitou, Toti et Serpentin au Pays des Songes' (1931).

Cadet-Revue: Mitou et Toti

With 'Zig et Puce' as his hit series, Saint-Ogan expanded his collaborations during the 1930s and 1940s. He created additional characters for other magazines, and saw commercial opportunities through adaptations for radio and stage shows, as well as sponsorships. Several of his creations also appeared in book collections published by Hachette and the Éditions Sociale Française (ESF). Between 1 January 1933 and 15 August 1939, Saint-Ogan was chief editor of Cadet-Revue, a bi-monthly magazine sponsored by the milk flavouring product Ovomaltine. His most notable contribution to this magazine were the boy-and-girl characters 'Mitou et Toti', originally created for a 1932 Ovomaltine flyer and a series of advertising comic strips in Dimanche-Illustré (1932-1933).

Cover drawings for Cadet-Revue issues #60 (15 June 1935) and 133 (1 July 1938).

In 1933, Mitou and Toti became characters in illustrated stories for Cadet-Revue, where they were quickly joined by the dachshund Serpentin. Originally created as Ovomaltine mascots, the characters quickly dropped their role as promoters of the virtues of the drink, and became heroes in a series of magical stories. Their adventures brought them to an animal land, a journey throughout the ages, toyland and a fairy tale country, where they meet characters from Charles Perrault's 'Mother Goose' stories, including Little Red Riding Hood, Bluebeard and Puss in Boots. The plot is sprinkled with sly political satire. Hachette released the picture books 'Mitou et Toti à Travers Les Âges' (1934), 'Serpentin' (1935) and 'Serpentin, Mitou et Toti' (1936). In 1943, 'Mitou et Toti à Travers Les Âges' was reprinted in Benjamin. Saint-Ogan also promoted Serpentin, Mitou et Toti on a radio children's program, hosted on Radio-Paris and Radio-Luxembourg.

'Jakitou Ministre'.

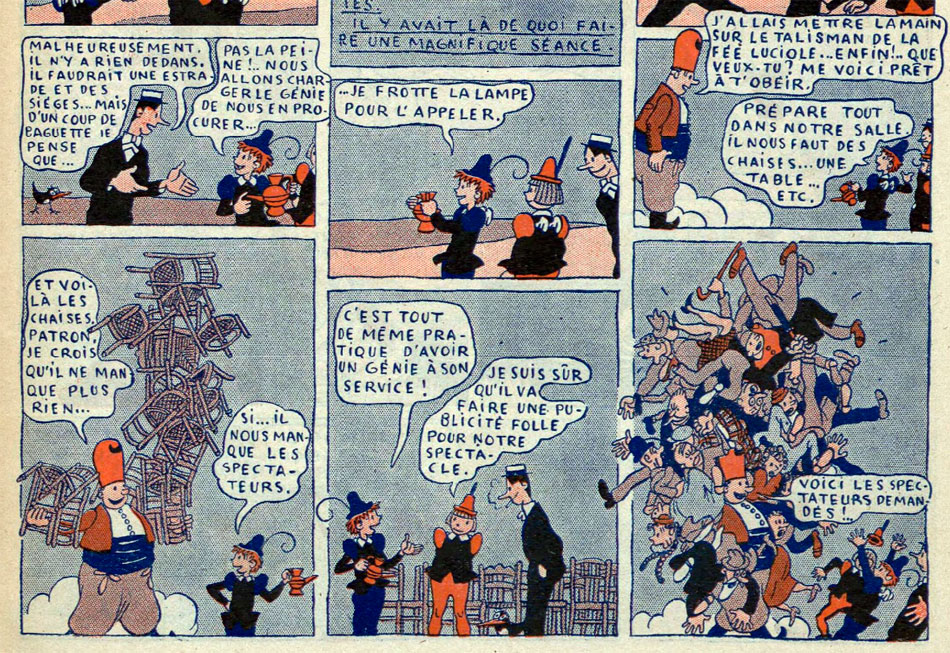

Cadet Revue: One-shot serials

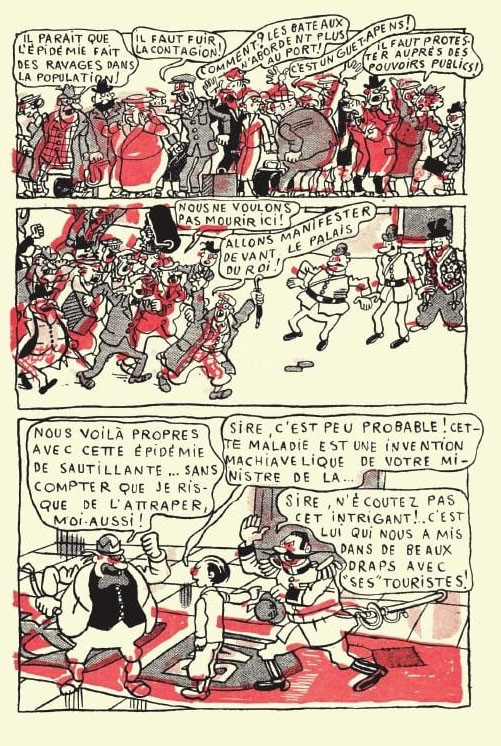

Also for Cadet-Revue, Saint-Ogan created the elf 'Toui-Toui', a servant of Merlin the wizard. In their sole story, published between November 1934 and August 1935, they travel to our modern-day Earth to inform people that magic is real, only to not be believed. After serialization, the story was collected in book format by Hachette. His next Cadet-Revue serial was 'Jakitou Ministre' (September 1935-October 1937), about a young boy who becomes Prime Minister of a fictional country. The story features some light-weight political satire. Contrary to many of Saint-Ogan's other comics, 'Jakitou' was never collected in book format, though he later recycled several plot elements for 'Zig et Puce Ministres' (1938). Between November 1937 and April 1939, Saint-Ogan created an epic science fiction serial for Cadet-Revue, 'Le Rayon Mystérieux' ("The Mysterious Ray"), about a journalist investigating three scientists who seem to be in contact with people from Venus. Again, the plot featured contemporary satire, including the politics of the 1930s.

Debut of Prosper the Bear in Le Matin of 16 February 1933.

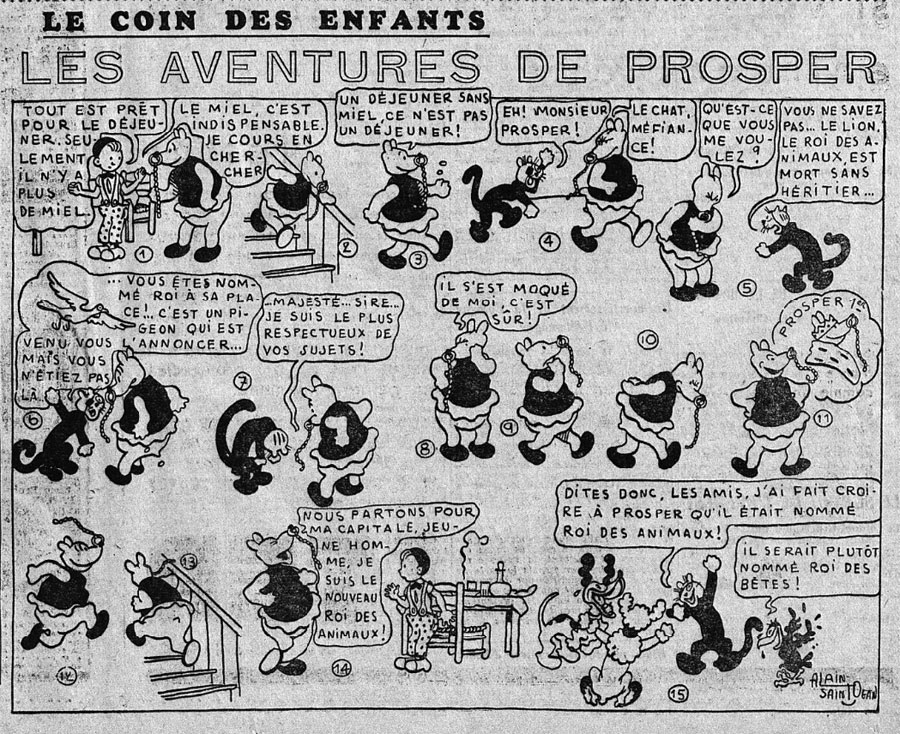

Prosper L'Ours

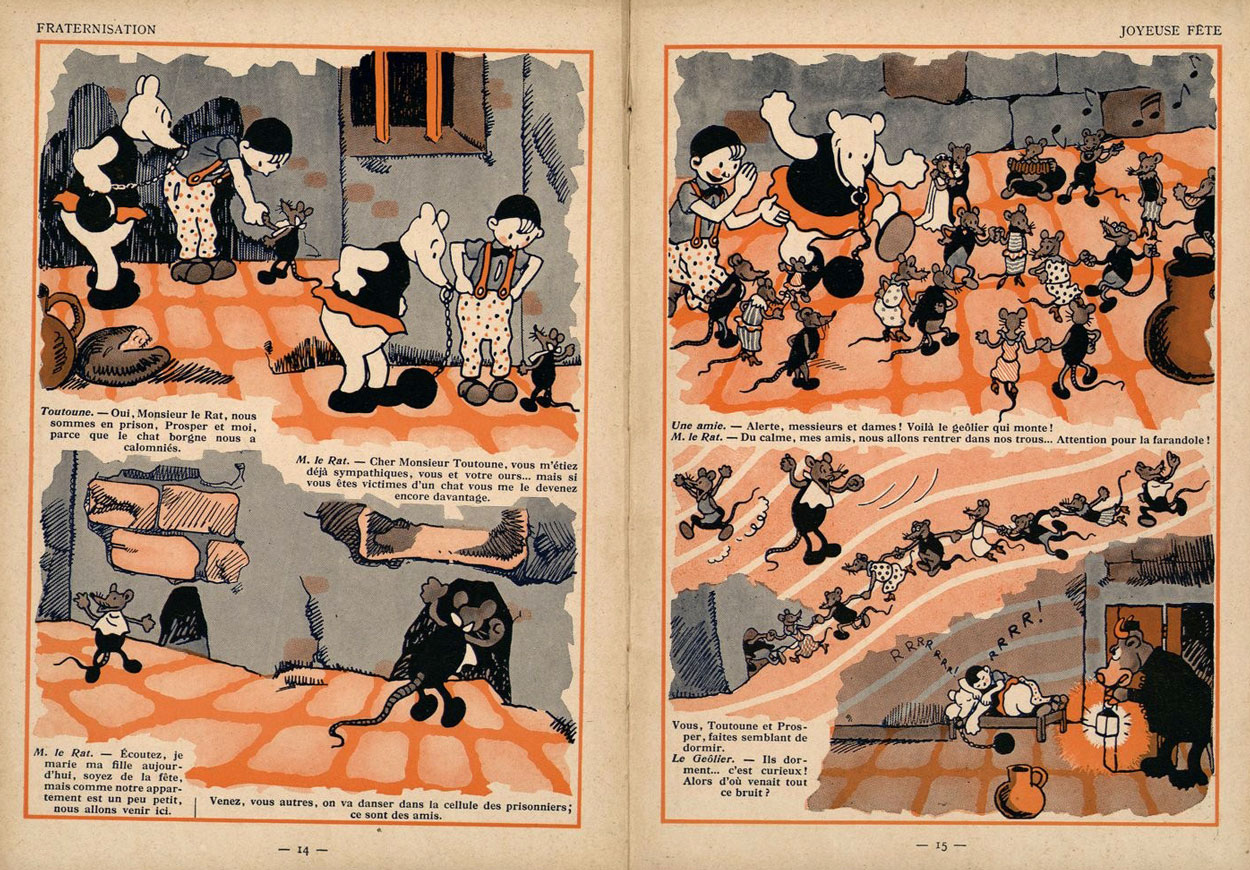

While still continuing 'Zig et Puce' in Dimanche-Illustré and filling most of Cadet-Revue, Saint-Ogan found time to create additional newspaper comics. One day, Saint-Ogan was contacted by Le Petit Journal with the request to make an educational comic. Saint-Ogan wrote a story about a young bear trainer who ends up in a country where all animals are anthropomorphic and have the ability to talk, giving him more of their perspective. Saint-Ogan sent the pages to Le Petit Journal's editorial board, but two weeks passed without receiving any feedback. Angered, he went to their offices and said that he would take the pages back. Once outside, Saint-Ogan cooled down and realized he had an appointment later that evening and not enough time to go back home and stash his artwork away. To avoid having to take them to his appointment, he gave them to a nearby friend who worked for the newspaper Le Matin, asking him to have the pages delivered to his house the next day. The next morning, Saint-Ogan waited in vain for the delivery boy to arrive. Again losing his temper, he phoned him and was surprised to find out that his comrade had given the pages to the chief editor of Le Matin, who now wanted to serialize them in his paper, marking the start of 'Prosper L'Ours'. Set in the land of the animals, the comic stars Prosper, an anthropomorphic white bear and his human friend Toutone. The bear's love interest is Madame Ursus, and his arch enemy, a one-eyed black cat. During its serialization from 16 February 1933 to 27 August 1939, Prosper became popular enough to be merchandised into dolls, seven comic books published by Hachette (1933-1940) and a 1935 play, staged by Thérèse Lenôtre. After World War II, the comic was reprinted in the newspaper Ce Matin-Le Pays (1950).

'Prosper et the Monstre Marin'.

Saint-Ogan always loved drawing animals, and he disagreed with the prejudice that they made stories more childish. Inspired by Walt Disney, Saint-Ogan also picked out Prosper to be adapted into an animated cartoon. With his brother Bertrand Saint-Ogan (pen name Bert-Malet), he made 'Prosper et Le Concours de Beauté' (1934), but it wasn't a huge success. In the 1930s, there was still a considerable amount of mystery on how the Disney Studios achieved their fluid animation and amazing technical effects. Saint-Ogan, like so many other amateur animators, was unable to unravel these secrets. He also found it difficult to organize an animation studio in France and obtain the necessary funding. On top of that, he just couldn't compete with Disney's strong market presence in movie theaters.

'Monsieur Poche'.

Monsieur Poche

When in October 1934 'Zig et Puce' came to an end in Dimanche-Illustré, Saint-Ogan moved on to create another feature for the paper. Serialized between 14 October 1934 and 10 October 1937, 'Monsieur Poche' was a gag comic starring a bald, corpulent, bespectacled, big-nosed man. Self-important, he always tries to lecture people using eloquent, high-brow expressions and theatrical poses. His "wisdoms" impress a young boy, Rafafia, and girl, Kiki, but in the process, Poche constantly makes a fool of himself. Poche owns a pet kangaroo, Salsifis, whose name was suggested through a readers' poll. He received the animal from an uncle in "Oceania". The marsupial is trained to fetch things, much like a dog, while Poche uses him as a sparring partner during boxing matches. Salsifis is sometimes seen talking, but it is unclear whether he can really communicate with humans, or just talks to himself. Poche's antics were compiled into four albums by publishing company Hachette.

In October 1937, 'Monsieur Poche' moved from Dimanche-lllustré to Cadet-Revue, where he remained until the final issue in August 1939. Between 17 October 1940 and 7 January 1943, 'Monsieur Poche' was reprinted in the children's magazine Benjamin. On 12 December 1948, Poche was also introduced in Saint-Ogan's signature series 'Zig et Puce' as a comic relief character. Between 1952 and 1955, 'Monsieur Poche' was revived for a new publication in Forces Nouvelles magazine.

'Princesse Irmine' (Dimanche Illustré, 31 July 1938).

When 'Monsieur Poche' disappeared from Dimanche-Illustré, Saint-Ogan in turn created the serial 'Princesse Irmine', printed between 17 October 1937 and 25 September 1938 in Dimanche-Illustré. Scripted by Maurice Kéroul (some sources incorrectly claim Paul Clérouc), it tells the story of Princess Irmine of Babina who, forced to marry the sovereign of a neighboring state, flees and embarks on a journey across the world, pursued by the agents of her father and her suitor.

While Poche is nowadays forgotten, he did leave a strong impression on the Belgian comic creator Michel Greg who, in the early 1960s, received permission from Saint-Ogan to reboot the character, much like he did around the same time with 'Zig et Puce'. He wanted to introduce Poche in Pilote magazine, but chief editor René Goscinny (himself a 'Zig et Puce' fan) felt Poche was "too 1930s" to be revived. However, he did like the idea of a loud-mouthed, self-important bourgeois and suggested that Greg simply made a modernized imitation. As such, Greg created a very similar comedic character in terms of personality and design: 'Achille Talon' ('Walter Melon'), who went on to become his signature creation.

Ric et Rac magazine

Between 1939 and 1944, Saint-Ogan was additionally present in Ric et Rac magazine, first with gags starring the resourceful and philosophical vagrants 'Galoche et Bitunet' (August 1939 - June 1940). However, the duo quickly enlist in the army, and the feature evolved into a form of good-natured soldier comedy based on Bitumet's laziness and Galoche's naiveté. His next creation for Ric et Rac was 'Potage' (September 1940-July 1944), a series of gags about a distracted bachelor, often inspired by the difficulties of war, as well as magical and poetic elements.

Editorial header illustrator for Benjamin (22 August 1940).

Benjamin

In the early 1930s, Saint-Ogan had begun making irregular illustrations for the children's magazine Benjamin, published by Jean Nohain. At the start, however, he was mostly involved in the magazine's non-print activities, like festivities and contests aimed at children. These included a 1933 children's drawing contest for the Printemps department stores, which had Saint-Ogan on the jury, along with Christophe and Émile-Joseph Pinchon. He also participated in radio broadcasts organized by Benjamin, a children's cooking contest, as well as the previously mentioned Cirque d'Hiver parade with the twelve penguins. In March 1935, Saint-Ogan and the rest of the Benjamin team were present at the Salon des Arts Ménagers, where he was perhaps one of the first comic creators signing autographs for his fans.

While the original run of Benjamin had come to an end in August 1939, Saint-Ogan became editor-in-chief of a new Benjamin series, published in Clermont-Ferrand between July 1940 and August 1944, and distributed during World War II in the "free zone" of France. During this period, his presence in Benjamin increased. Several of his earlier creations reappeared in reprint stories, like 'Zig et Puce', 'Mitou et Toti' and 'Monsieur Poche', with Zig, Puce and Alfred even making it to magazine mascots. Some of his comics in the magazine were new, like 'Trac et Boum' (22 August 1940 – 26 November 1942), about two boys who travel through a fairy tale country, accompanied by a talking crow named Caraco and the clumsy fairy Rutabaga. Their adventures were collected in book format by Édition Sociale Française. Saint-Ogan also created a gag comic about a black fox terrier with white paws, 'Faubert Chez Les Hommes', printed in Benjamin between 10 December 1942 and 18 March 1943.

'Les Aventures de Trac et Boum' (book publication, 1946).

Far-right cartoons and nationalism

During the 1930s and 1940s, Saint-Ogan also provided political cartoons to far-right magazines like L'Action Française, Pantagruel and Le Coup de Patte, some of which contained antisemitism and colonial racism. During the Nazi occupation of France, he stayed in Clermont-Ferrand, making propaganda cartoons and illustrations, glorifying marshal Henri Pétain and the Vichy Regime. A 1941 drawing was specifically intended to be hung in classrooms. Saint-Ogan's Nazi collaboration is particularly jarring, given that he started his career drawing anti-German propaganda cartoons. Oddly enough, unlike many others, he was never arrested after the war.

In 1945, he was also named president of the Union of Children's Newspaper Cartoonists (SDJE), becoming very resistant against the flood of American comics in France after World War II. Since Saint-Ogan had been the most successful French balloon comic artist before the war, he received admiration from more francophone people who regarded him as a "true French artist". In reality, Saint-Ogan's comics had been strongly influenced by U.S. comics in the early years.

Nizette et Jobinet' (Baby Journal, 1 April 1949).

Post-war comics and cartoons

In the early post-war years, between March 1946 and May 1947, Alain Saint-Ogan was present in the short-lived magazine Tour à Tour, drawing gags with the magazine mascot 'Monsieur Touratour' (1946-1947), as well as the serial 'Manou, La Petite Fée' (1946-1947). Subsequently, he joined La Vie Catholique Illustrée, contributing the boys' adventure features 'Cyprien et Gédéon' (1948) and 'Dani et Martinette' (1949), while reusing elements from his pre-war 'Mitou et Toti' comic. An additional adventurous duo was 'Potte et Rik', published in Jeudi Matin (1949-1950). For Marijac's children's magazine Baby Journal and its follow-up Cricri Journal, Saint-Ogan drew 'Nizette et Jobinet' (1 April 1948- 15 April 1950), about a young girl and boy who meet a talking raven and then experience a time travel adventure. Between 1948 and 1953, Saint-Ogan was also a productive press cartoonist for Le Parisien Libéré, returning to the title during the 1960s and 1970s. In 1974, a selection by Eric Leguebe of Saint-Ogan's press cartoons was released by Éditions Serg under the title 'Alain Saint-Ogan, Dessinateur de Presse'.

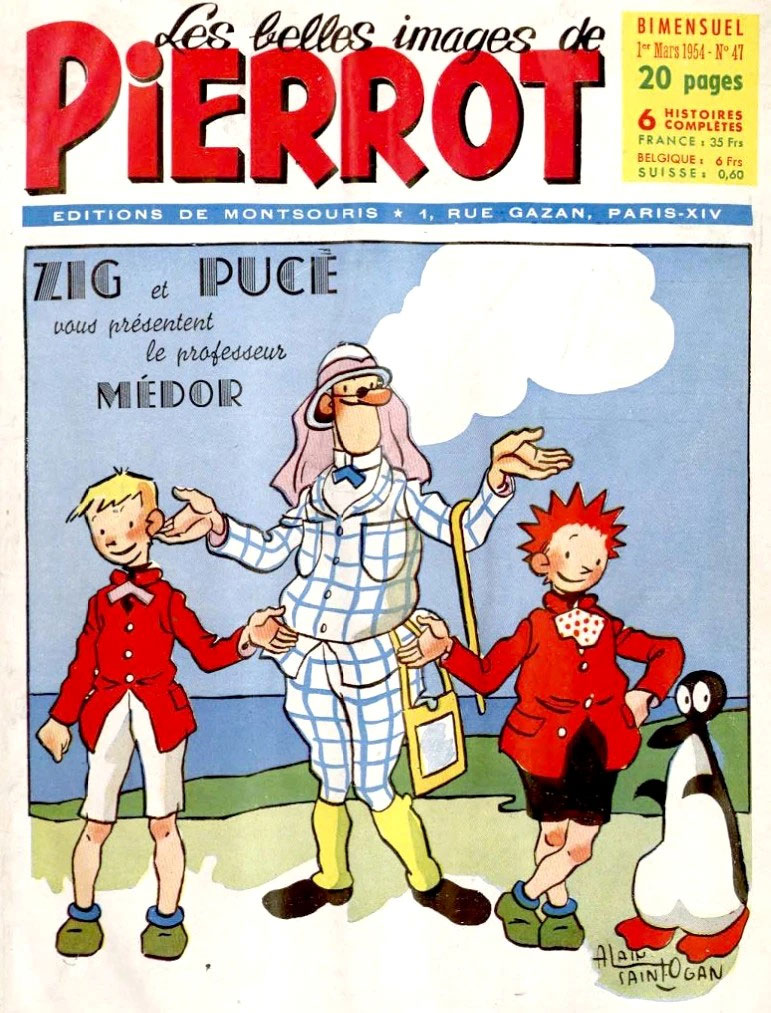

'Zig et Puce' on the cover of Les Belles Histoires de Pierrot (1 March 1954).

Zig et Puce in the post-war period (1946-1955)

After World War II, 'Zig et Puce' enjoyed new adventures in France-Soir Jeudi, a children's magazine launched by France Soir. Despite lasting 59 issues and reintroducing his characters to a new generation of young readers, Saint-Ogan was unsatisfied with the quality of the publication, a direct result of the lack of decent printing materials due to the war years. After France-Soir Jeudi folded on 9 July 1947, Saint-Ogan took his famous duo to another juvenile magazine, Zorro, where the boys remained in print until 13 November 1949. Zorro's publisher Chappelle took his chance by giving Zig et Puce their very own weekly comic magazine on 20 November 1949. Apart from Saint-Ogan's signature series, Zig et Puce magazine also ran Claude Henri's 'Duguesclin' and André Oulié's 'Robin L'Intrépide'. However, the magazine only lasted a year and 32 issues, before folding on 25 June 1950. In 1950 and 1951, 'Zig et Puce' reappeared in the pages of Zorro.

Between 15 December 1952 and 1954, 'Zig et Puce' was serialized in the magazine Les Belles Images de Pierrot (Editions de Montsouris). While presented as "new" stories, Saint-Ogan recycled the plots of other illustrated books and comic series he had drawn in the past by just adding Zig, Puce and Alfred in the narratives. It was a sign that he was slowly but surely running out of ideas. Additionally, he also struggled with arthritis. On 19 July 1956, 'Zig et Puce' was discontinued. In total, Saint-Ogan had drawn 18 long stories with his characters over the years, occasionally assisted by André Rigal.

Alain Saint-Ogan during a radio broadcast (Paris-Soir,(7 November 1935).

Radio career

Since 1928, Saint-Ogan also had a long-running association with the radio. Besides making illustrations for the magazine Radio-Programme, he promoted many of his comic series ('Zig et Puce', 'Prosper L'Ours', 'Mitou et Toti') by having them adapted into radio plays for Radio-Paris and Radio-Luxembourg, which he sometimes narrated himself. For young readers, it made his comics a more interactive experience. Between 1942 and 1944, Saint-Ogan made regular appearances in André Reval's juvenile program 'Quinze Ans' on Radio-Paris. After the war, Saint-Ogan went on to produce and host radio shows on Radio Monte-Carlo and Radio Andorra. Between 1950 and 1957, he and Arlette Peters produced the weekly children's program 'Les Jeudis de la Jeunesse' on Paris Inter (1950-1957), a continuation of Jacques Pauliac's earlier 'Beaux Jeudis' broadcasts. For the Thursday show 'C'est Jeudi', he adapted 'Zig et Puce' and 'Monsieur Poche' into audio plays.

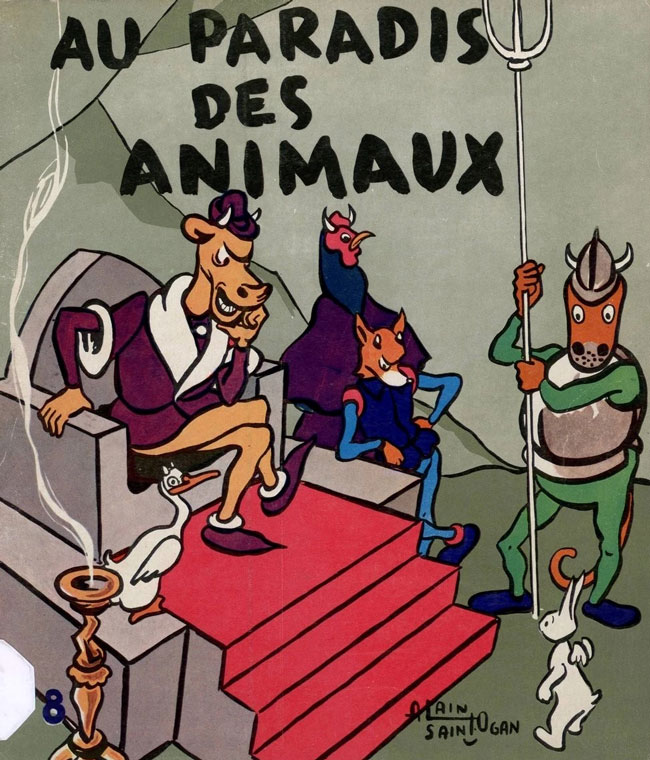

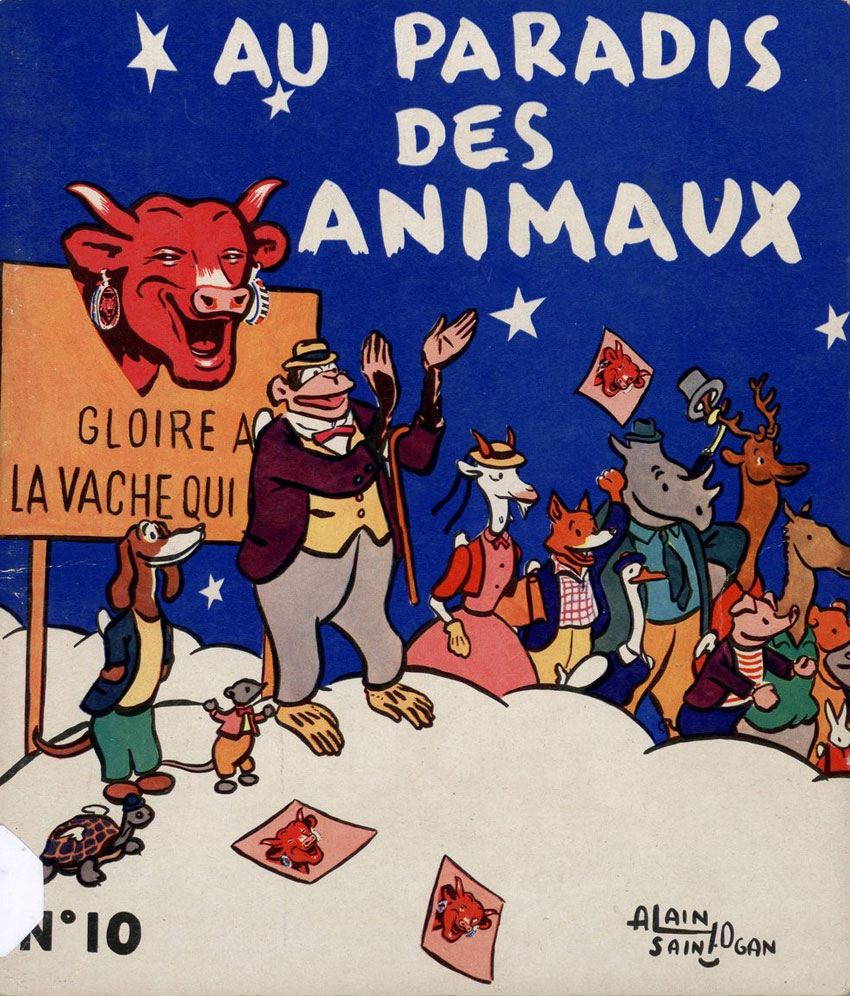

During the 1950s, the director of the Bel cheese factories asked Saint-Ogan to create radio serials starring the bovine mascot of the brand's flagship cheese product, La Vache Qui Rit ("The Laughing Cow", originally designed by Benjamin Rabier). In his earlier comics, Saint-Ogan had regularly visited magical countries, like the land of the animals, most notably in his 1930s 'Prosper l'Ours' comic. In 1954, Saint-Ogan and scriptwriter René Blanckemann reused the narrative about a country with talking animals for their Vache Qui Rit broadcasts, having the cow and other animals enjoy adventures in an afterlife paradise for animals. When Saint-Ogan told Mr. Bel that he would also put La Vache Qui Rit in this Heaven, Bel first objected: "But then you kill her?". Saint-Ogan replied that he didn't, but gave her "immortality", instead. This answer satisfied Bel and he greenlighted the project.

Between 1954 and 1959, episodes of 'La Vache Qui Rit au Paradis des Animaux' were broadcast on Radio-Monte-Carlo, Radio-Luxembourg, Radio-Andorra, Radio-Tanger International and Radio-Africa-Maghreb. To accompany the promotional campaign, Saint-Ogan also made a series of ten 24-page comic booklets of 'La Vache Qui Rit au Paradis des Animaux', which could be obtained by collecting the stamps inside the La Vache Qui Rit cheese boxes. In 1959 and 1960, Saint-Ogan produced an additional radio series for Bel, 'Cric et Crac à Travers les Âges', which also came with 13 comic booklets of 8 pages each.

Except for 'Les Jeudis de la Jeunesse', most of Saint-Ogan's radio recordings have not been conserved.

Graphic contributions

In addition to his comic and radio productions, Saint-Ogan was also a prominent illustrator for publishers like Figuières, Hachette, Arthème Fayard, Le Liseron, Elzévir and La Table Ronde. For instance, Saint-Ogan illustrated novels by Luc Mani ('Le Tour du Monde d'Hector Snapillon', 1926), Pierre Humble ( 'Caddy-Caddy', 1929), Thérèse Lenôtre ('Pototo Fait de la T.S.F.', 1929), Marthe Fiel ( 'Bertin L'Indécis', 1930) and D. Meire ('La Drôle de Guerre de Monsieur Hixe', 1967). He livened up the pages of historian Jacques Bainville's 'Les Étonnerements de Michou' (1934) and collaborated with Camille Ducray on the science fiction novel 'Le Voyageur Immobiel' (1945). Saint-Ogan also wrote one illustrated novel by his own hand, 'Le Mariage d'Hector Coderlan' (Hachette, 1930).

Recognition

Saint-Ogan lived long enough to receive various awards, honorary titles and be rightfully recognized as one of the pioneers of French comics. In 1967, he became the first cartoonist ever to have his effigy coined on a medal. In 1973, the veteran was named honorary jury member of the International Comic Festival of Toulouse and honorary president of the very first International Comic Festival of Angoulême. At Angoulême, the prize for "Best Comic Book" was named the "Prix Alfred", after Alfred the penguin. Since 1988, the award has been renamed the Alph-Art, after the unfinished 'Tintin' story 'Tintin and the Alpha Art'). A road in the village of Torcy has additionally been named after Saint-Ogan.

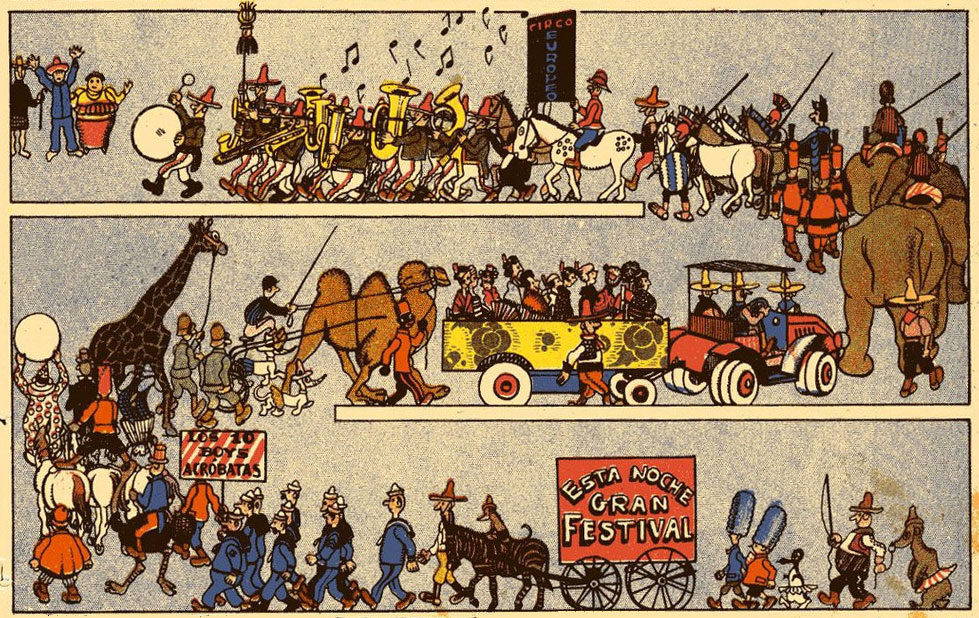

The circus parade from Alain Saint-Ogan's 1931 story 'Zig et Puce cherchent Dolly' (Spanish-language edition).

Zig et Puce: Greg revival (1963-1969)

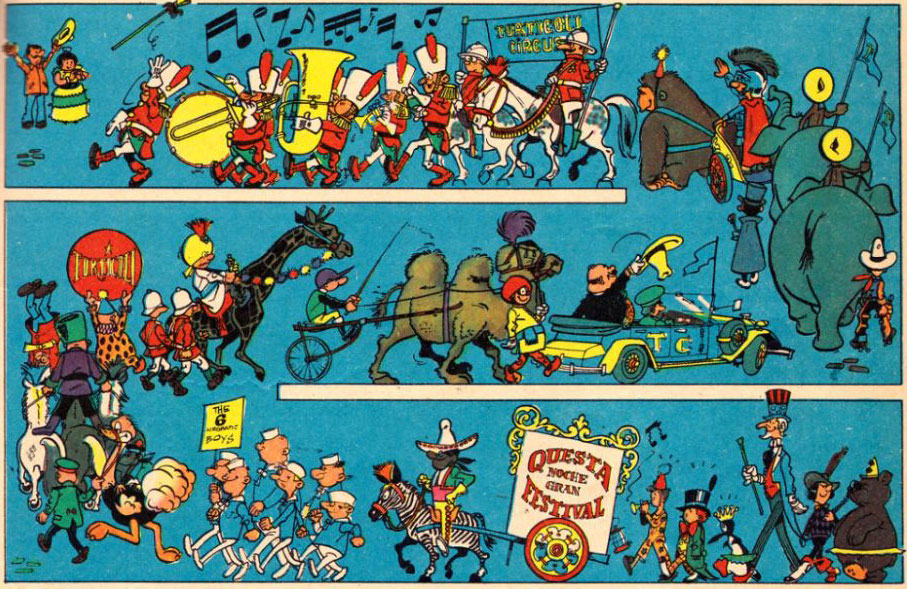

Although Saint-Ogan had discontinued 'Zig et Puce' in 1956, one decade later the series was revived in Tintin magazine. Art director and principal comic artist Hergé had always named Saint-Ogan his strongest graphic influence and so he wanted to help his idol be reintroduced to new generations of comic readers. Michel Greg, another longtime admirer, had the same idea, especially because he took pity on Saint-Ogan, who was now old and an amputee. Greg consulted Saint-Ogan on how to respectfully reboot 'Zig et Puce' for a modern generation. He also gave the veteran 25 percent of what he earned on the series. Retitled 'Zig, Puce et Alfred', Greg wrote and drew six new stories, assisted by Vicq and Dupa. The character Dolly was renamed Sheila and her uncle was changed into her father. Greg also decided to give him a name, Poprocket. The rebooted version of 'Zig et Puce' ran in Tintin from the 26 March 1963 issue (#13) until the 27 March 1969 issue (#12). Under the title 'Kees en Klaas', it also appeared in Tintin's Dutch-language edition. As a tribute to the series' creator, Greg sometimes redrew entire scenes from Saint-Ogan's earlier 'Zig et Puce' stories, for instance the circus parade in 'S.O.S. Sheila' (1966).

In old age, Saint-Ogan remained grateful to Hergé and Greg. In 1972, when he turned 77, he wrote to Tintin magazine, asking them whether they would mind changing their advertising slogan ("for readers between 7 and 77"), so he could continue reading their magazine.

Greg's recreation of the circus parade in his 1966 'Zig et Puce' story 'S.O.S. Sheila'.

Final years and death

In the 1960s, Saint-Ogan's health started to decline, and one of his legs had to be amputated. In 1961, he published an autobiography, 'Je Me Souviens de Zig et Puce et de Quelques Autres' (Éditions de la Table Ronde, 1961) and in the following year, he made his final appearances on the radio in a series of programs in which he told his memoirs, interviewed by Arlette Peters. He still kept drawing humorous cartoons for Le Parisien Libéré and making advertising illustrations. In 1969, he witnessed the comic fanzine Phénix dedicating an entire issue to 'Zig et Puce'.

In 1974, Alain Saint-Ogan passed away at age 78 in Paris, never living to see Claude Moliterni and Hachette's collective homage album, 'Zig et Puce au XXIe Siècle: Hommage à Alain Saint-Ogan' (1974), featuring graphic and written tributes by Pierre Couperie, Henri Filippini, Edouard François, M. Fleurent, André Franquin, René Goscinny, Albert Uderzo, Michel Greg, Hergé and Claude Moliterni himself.

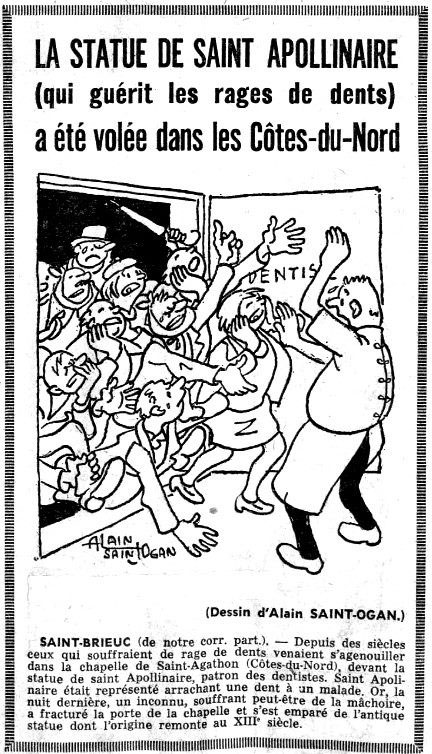

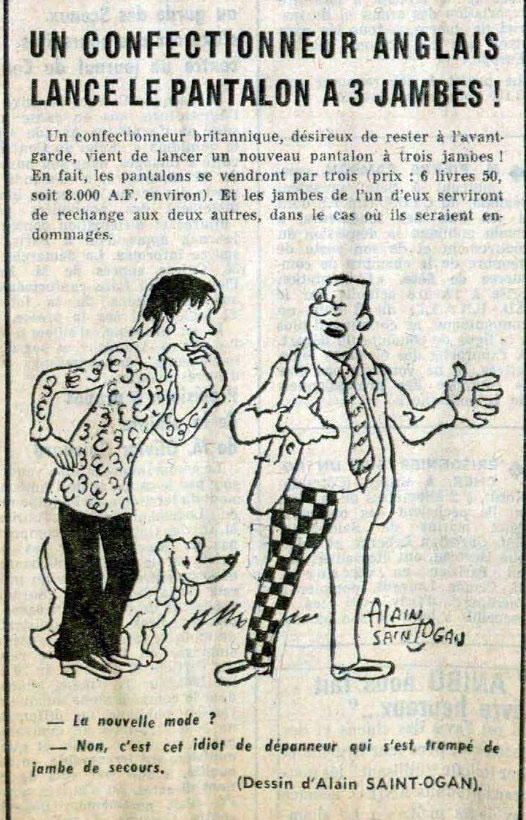

Editorial cartoons for Le Parisien Liberé (1968, 1972). Translation of the second cartoon: "The latest fashion?" - "No, this was done by that fool of a repair man, who mistook the spare leg."

Legacy and influence

Along with Louis Forton, Émile-Joseph Pinchon and Benjamin Rabier, Saint-Ogan can be considered one of the most important and influential French comic creators of the early 20th century. But while Forton and Pinchon kept working in the text comic format, with narration and dialogue printed underneath the images, Saint-Ogan popularized the balloon comic and so heralded the birth of the modern-day French comics, also known as "bandes-dessinées". A savvy businessman, he maximized the popularity of his characters by merchandising them through collectable books, radio and stage play adaptations, toys and figurines. He organized public events and media stunts around his creations, attracting huge family audiences. From this perspective, he proved the commercial viabilities of children's comics in France. Having built this pre-war reputation, his status after World War II increased, despite his dubious war past. Very early on in comics fandom, he was recognized as the most significant comic creator in the development of the French and Franco-Belgian comic industries.

However, from an artistic viewpoint, Saint-Ogan's legacy is more contested. Early in his career, he made cartoons and illustrations for adult audiences, mostly of a propaganda or political-satirical nature, while eventually becoming a pure children's author. Despite introducing an innovative and influential balloon comic style in his home country, Saint-Ogan soon settled on it, never moving beyond creating fantasy, funny animal and science fiction stories for children. They were drawn in a loose style, with naïve plots where characters just fall from one situation into another. As comic historian Dominique Petitfaux observed, Saint-Ogan's stories are "happy, but lack plot coherence, believability and serious documentation." Saint-Ogan also often recycled set-ups and narratives from previous comics. He had a penchant for tales about two young children and an anthropomorphic pet, set in fairy tale worlds or outer space. Some plots and gags previously used for other series were readapted into others, down to political satire originally intended as parental bonus being watered down into straightforward children's stories. Being able to repurpose old scripts for new commercial taskmasters, different magazines and media was undeniably a good lucrative move, but comic fans who dig through his body of work will often encounter a feeling of déjà-vu.

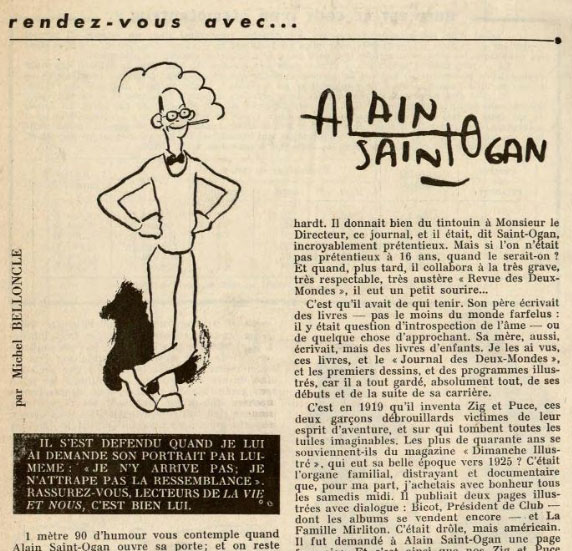

Self-portrait for a magazine article.

Influence

In France, Saint-Ogan was an influence on René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo. As a little nod, a Roman prison guard in 'Astérix the Gladiator' is named Ziguépus in the original French-language version. In 2017, the 95-year old Frenchwoman Genéviéve Gautier became the oldest person in history to debut as a comic author when she drew a fanfiction story about Alfred the penguin. In Belgium, Saint-Ogan was Hergé's prime influence. He admired his crisp artwork, use of speech balloons and clear method of storytelling. Hergé sometimes published drawings by Saint-Ogan in his own children's magazine Le Petit Vingtième and, in April 1931, he met his idol in his apartment in Paris. Saint-Ogan gave him professional advice and also an original 'Zig et Puce' page, titled 'Gloire et Richesse'. It depicts the cast members being interviewed by nosy journalists, a scene Hergé would invoke no less than three times in 'Tintin' ('Tintin in Africa', 'Tintin in America' and 'Red Rackham's Treasure') and one time in 'Jo, Zette et Jocko'. The influence of 'Zig et Puce' can also be noticed in Hergé's 'Quick & Flupke'. Much like Zig and Puce have an animal companion in Alfred the penguin, Tintin has Snowy the dog, while Jo and Zette have a pet chimpanzee, Jocko. The globetrotting adventure serials of 'Zig et Puce', particularly their voyage to "America", where they are captured by "Indians", shares a strong connection with the later 'Tintin' story 'Tintin in America'. In 'Zig, Puce et La Petite Princesse' (1933), Zig and Puce read a tourist brochure about the fictional country where the titular princess lives, a visual idea also found in the 'Tintin' story 'King Ottokar's Sceptre' (1939). Comics historian Thierry Groensteen devoted an entire essay about Saint-Ogan's influence on Hergé. One of the most notable differences he observed between both comic legends was that Hergé eventually started using more documentation and streamlining his artwork, setting the quiffed reporter's adventures in a more plausible reality.

Other Belgian artists influenced by Alain Saint-Ogan were Buth, Michel Greg, André Franquin and Marc Sleen. Saint-Ogan's 'Monsieur Poche' was the direct inspiration for Greg's signature series 'Achille Talon' ('Walter Melon'). In The Netherlands, Saint-Ogan has been cited as an inspiration by Gé Wasco and Joost Swarte. Kees Kousemaker, founder of the Amsterdam comics store Lambiek, and his longest-running salesman Klaas Knol, were often referred to as "Kees en Klaas" by customers and associates, not only because these were their actual names, but also in reference to the Dutch-language names of 'Zig et Puce'.

'Zig et Puce' also had an impact on the French language. Whenever Zig and Puce defeat a villain, they say to him: "T'as le bonjour d'Alfred!" ("Alfred sends you his greetings!"). Since the 1920s this has become a popular saying, often used in situations where somebody takes vengeance on others.

Secondary literature

Between 1995 and 2001, the complete editions of 'Zig et Puce' have been reprinted by Glénat, with additional research by Dominique Petitfaux. Another wealth of information is provided by the website zigpuceealfred.wordpress.com, hosted by Frédéric Baylot. For those interested in Alain Saint-Ogan's life and career, Thierry Groensteen's biography, 'L'Art de Alain Saint-Ogan' (L'An 02, 2007), is highly recommended. Another insightful study into Alain Saint-Ogan's body of work is the 2009-2010 master thesis 'Alain Saint-Ogan et l'Univers Culturel de l'Enfance' by Julien Baudry for the Université Paris Diderot.

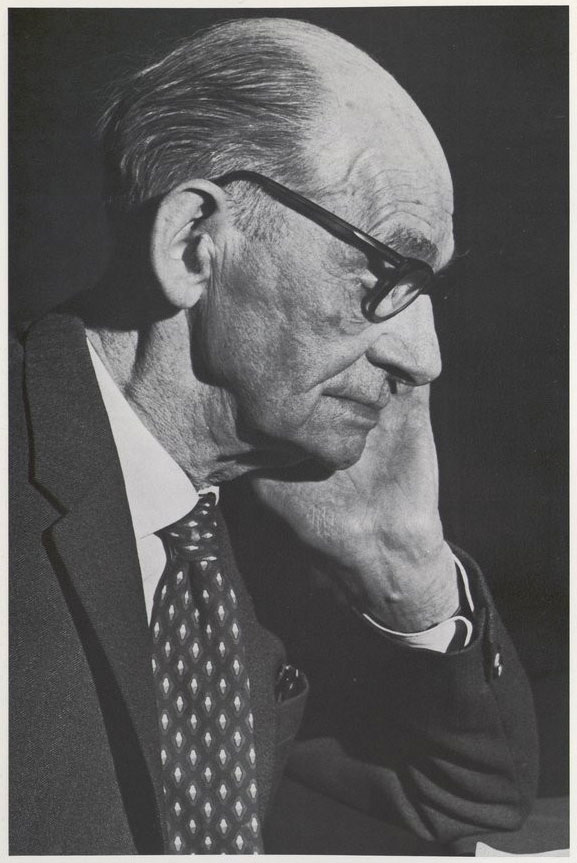

Alain Saint-Ogan, 1970s.